Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

496 Freedom Riders

Throughout the fall, these and other incidents, plus a renewal of the

boycott, fueled an effort by moderate and image-consciousness businessmen

to wrest control of local politics from Connor’s grasp by replacing

Birmingham’s commission form of government with a more open mayor-

council system. But the November referendum victory of the group known

as Citizens for Progress did not lead directly to desegregation or to Connor’s

political demise. Even though Connor lost to former lieutenant governor

Albert Boutwell in the spring 1963 mayoral race, he retained his position as

police commissioner long enough to stymie the movement’s efforts to crack

what some called the most segregated city in America.

21

Connor’s defeat in the April 2 runoff primary was part of a larger drama

that placed Birmingham at the center of the civil rights struggle during the

spring of 1963. This was the unforgettable season that brought SCLC’s

Project C (for “Confrontation”) to the city; that saw thousands of nonviolent

demonstrators march in the streets, only to be pushed back by police dogs

and high-pressure fire hoses; that produced King’s “Letter from a Birming-

ham Jail,” the controversial children’s marches, and the movement’s greatest

victory to date. To a nation and a world shocked by searing images of police

brutality and mass marches, the scale and intensity of Project C represented

something new and unprecedented, an escalation of conflict that overshad-

owed earlier crises, including the Freedom Rides. But to close observers of

the freedom struggle in Alabama, the 1963 Birmingham crisis also evoked

memories of the 1961 Freedom Rides. The provocative combination of na-

tional and local movements, the personal duel between Connor and

Shuttlesworth, and the involvement of several former Freedom Riders all

suggested an element of continuity. When King balked at supplementing

the depleted supply of adult marchers with younger activists, it was the Bev-

els and CORE Freedom Rider Ike Reynolds who forced the issue by orga-

nizing the first children’s march. Employing the same brinksmanship that

they had displayed during the Freedom Rides, the Bevels, along with

Shuttlesworth and the anti-hero Connor, did more than anyone else to push

the crisis to a point where there was no turning back from confrontation and

climactic resolution.

22

The legacy of the Alabama Freedom Rides was also apparent in the con-

current Freedom Walkers episode. On April 20, just as Project C was heat-

ing up, William Moore, an eccentric twenty-five-year-old white Baltimore

postman and CORE member, hand-delivered a letter to the White House

announcing his intention to conduct a one-man “Freedom Walk” from Chat-

tanooga, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, where he hoped to deliver a

second letter to Governor Ross Barnett. A veteran of the Route 40 sit-in

campaign and a friend and admirer of Jim Peck’s, Moore had sought funding

and formal endorsement from the Baltimore chapters of CORE and the

NAACP. But both groups turned him down, arguing that his insistence on

traveling alone and wearing provocative signboards with the words “End Seg-

Epilogue: Glory Bound 497

regation in America,” “Eat at Joe’s—Both Black and White,” and “Equal

Rights for All Men (Mississippi or Bust)” made the proposed trip much too

dangerous. Peck counseled Moore to “get a group to walk with you,” but

Moore was determined to set out by himself.

After traveling to Chattanooga by bus, he started walking down High-

way 11 on the morning of April 21, adorned with a front-and-back sandwich

board and pushing a small postal cart containing a satchel of clothes and

mimeographed copies of letters to President Kennedy and Governor Barnett,

which he hoped to distribute to passersby. Two days of walking took him out

of Tennessee, across a narrow corner of northwestern Georgia, and into north-

eastern Alabama, where he spent the night in the town of Fort Payne. On the

morning of the twenty-third, he resumed his lonely journey, heading south-

ward toward Birmingham, where his hero Peck had been beaten two years

earlier. While passing through the village of Collbran, he had a disturbing

encounter with a local Klansman and grocery store owner named Floyd

Simpson, who, along with a second Klansman, jumped in a pickup truck and

began following Moore down Highway 11. In Collinsville, Moore had a sec-

ond confrontation with Simpson, who called him an atheistic Communist

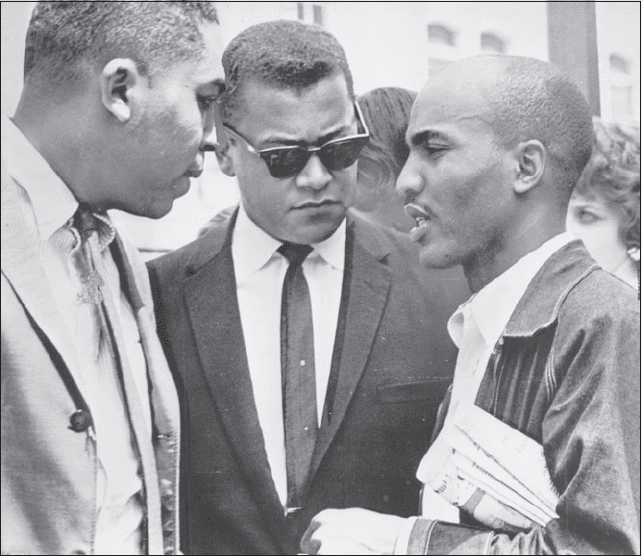

Former Freedom Riders Jim Lawson (center) and Jim Bevel (right) confer with

the Reverend Kelly Miller Smith (left) prior to a civil rights march in Birmingham,

May 7, 1963. (Courtesy of Nashville Tennessean)

498 Freedom Riders

and warned him that he wouldn’t “make it past Birmingham.” Less than two

hours later, Moore’s freedom walk ended when he was gunned down just

outside the village of Keener. The two .22-caliber rifle bullets that killed

him were promptly traced to Simpson’s gun, and the Klansman was arrested

for murder.

In the immediate aftermath of Moore’s death, the national press treated

the incident as a major story with obvious connections to the Freedom Rides,

but both press and public attention soon shifted to the more compelling daily

confrontations in Birmingham. In a press conference held the day after the

shooting, President Kennedy characterized Moore’s murder as “an outra-

geous crime” and offered “the services of the FBI in the solution of the crime,”

even though he admitted that the federal government did “not have direct

jurisdiction.” The promised help never materialized, however, and any hope

of conviction ended five months later when a local grand jury refused to issue

an indictment.

23

In the meantime, movement activists made several attempts to memori-

alize Moore’s sacrifice by completing his Freedom Walk. On April 26 John

Lewis and more than a hundred students carrying signs pronouncing that

Moore “Died for Love” and asking “Who Will Be Next?” marched from

Fisk to a downtown Nashville federal building. On the following morning

CORE and SNCC—the same two organizations that had taken the lead dur-

ing the Freedom Rides—issued a joint statement declaring their intention to

collaborate on a Moore Memorial Trek. Four days later two groups of Free-

dom Walkers were on the road, despite Governor Wallace’s warning to Jim

Forman that “your apparent desire to bally-hoo this tragic incident for po-

litical and selfish reasons would be an affront to the dignity of the people of

Alabama and to the family of the deceased.” “I strongly urge you to abandon

your project,” he added. “If you persist, the laws of Alabama will be strictly

enforced.” One group of Freedom Walkers—an interracial and interregional

band of ten experienced CORE and SNCC activists that included CORE

field secretary Richard Haley and former Freedom Riders Bob Zellner, Zev

Aelony, and Bill Hansen—set out from Chattanooga; and a second group of

eight black Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights activists led by

Diane Nash Bevel gathered in Keener, at the scene of the murder, before

heading southward. At a premarch press conference, Haley described the

Freedom Walkers’ goal of reiterating Moore’s simple notion that “the idea

of human brotherhood” could be expressed “by a peaceful walk through the

American countryside.” But there would be no peaceful walk for either group.

The Nash group was arrested in Gadsden, barely ten miles into their

journey, and the Haley group did not fare much better. Surrounded by heck-

lers in Tennessee and Georgia during the first two days of the trek, they

were arrested on the afternoon of the third day as soon as they crossed the

Alabama line. As state troopers rounded them up, using electric cattle prods

on at least two of the Freedom Walkers, a crowd of angry whites shouted

Epilogue: Glory Bound 499

racial epithets. One man shrieked, “Get the goddamn communists,” and an-

other yelled, “Throw them niggers in the river. Kill the white men first.” Taken

to the county jail, all ten Freedom Walkers refused bail and were later trans-

ferred to Kilby State Prison, where they were kept on death row for several

weeks. On May 16, the day after the transfer to Kilby, a new group of eleven

Freedom Walkers took to the road in Keener, but they too were arrested. In

early June, following the release of the Haley group, several Freedom Walkers

joined with other CORE, SNCC, and SCLC activists to organize a short-lived

coalition known as the Gadsden Freedom Movement. Following a series of

sit-ins and marches, the Gadsden Freedom Movement made an attempt to

resume Moore’s march on a mass scale on June 18, and this time more than

450 Freedom Walkers ended up in jail. Though somewhat weakened, the

Gadsden Freedom Movement continued to organize sporadic demonstra-

tions for another six weeks, and on August 3 a fifth and final attempt to spon-

sor a Freedom Walk led to a staggering 683 arrests.

Hoping to draw national attention to this and other episodes of escalat-

ing police repression in Gadsden, Jim Farmer assembled a celebrity-packed

delegation that included actors Marlon Brando and Paul Newman, but a

planned march to dramatize the situation was called off when CORE attor-

neys advised Farmer not to defy a local court injunction prohibiting addi-

tional demonstrations. Indeed, when it became clear that neither the Justice

Department nor the federal judiciary was willing to intervene on behalf of

the Gadsden demonstrators, both the Gadsden Freedom Movement and the

broader Freedom Walker campaign collapsed. Although legal wrangling over

the Gadsden cases would continue for another year, movement leaders, real-

izing that the Freedom Walks were not going the way of the Freedom Rides,

quietly moved on to other, more promising projects before the end of the

summer.

24

As the last chapter of a two-year-long saga initiated by the Alabama Free-

dom Rides, the ill-fated Freedom Walker campaign was a major disappoint-

ment for the movement. But, like the Albany campaign, it provided local as

well as national movement leaders with a refined sense of the realities of

struggle in the Deep South. Most important, it confirmed the nonviolent

movement’s vulnerability in the absence of meaningful legal and constitu-

tional protection. Without resolute federal intervention, there was only so

much that even the bravest of activists could accomplish in a state like Ala-

bama, where legal and extralegal retribution and white supremacist extrem-

ism were a fact of life long after the bus stations were desegregated. One

telling barometer of this climate of fear was the inability of Alabama’s home-

grown Freedom Riders to return to their native state without endangering

themselves and their families. For John Lewis, Catherine Burks Brooks, John

Maguire, Bill Harbour, and others, it would be years before being a “Free-

dom Rider” was detached from social ostracism, economic intimidation, and

potential violence. “Be best for you not to come,” Harbour’s mother advised

500 Freedom Riders

in May 1961, and with the exception of one brief and furtive visit later in the

year, he stayed away from Piedmont, where he was born and raised, until

mid-decade. Despite pressure from the White Citizens’ Councils, his extended

family remained in Piedmont, and Harbour eventually reconnected with kin

and community in Alabama. But in the early 1960s the minimum price of

radical dissent in Alabama was temporary exile. For Harbour, who lived to

see substantial progress in his home state, including the election of both his

younger brother Jerry and a cousin to the Piedmont city council, this price

ultimately proved bearable, justifying the sacrifices that he and others had

made. But, in the dark and difficult period following the Freedom Rides, few

Alabamians, black or white, would have predicted such a positive outcome.

25

IN THE HEART OF THE DEEP SOUTH, as we have seen, the Freedom Rides

inadvertently spawned an era of racial polarization and political resistance.

Here, with the notable exception of metropolitan Atlanta, the pace of social

change actually slowed for a time, and the quality of life for many blacks got

worse before it got better, triggering widespread disillusionment and despair.

Indeed, if the situation in Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, and southwestern

Georgia had been the only measure of the Freedom Rides’ impact, the non-

violent movement’s claim to victory would have been in some jeopardy. For-

tunately for the movement, this pattern of reactionary defiance did not hold

in other areas of the South and its borderlands. While there was plenty of

grousing about black militants, outside agitators, and federal meddling in

local affairs, the dominant reality in most of the region was slow but steady

progress toward desegregation. Not only was compliance with the ICC or-

der all but universal outside the Deep South by early 1962, but the sudden-

ness of transit desegregation, however grudging or involuntary, seemed to

foster a growing resignation that desegregation of other institutions was in-

evitable and even imminent. Unlike the Deep South, where the threat of

massive and even violent resistance remained an integral part of regional

culture, the rest of the area below the Mason-Dixon line seemed to be mov-

ing toward political moderation and away from the sectionalist siege mental-

ity associated with the “Solid South.” As early as November 1961 public

opinion polls revealed that, outside of Mississippi and Alabama, an overwhelm-

ing majority of Southern whites had concluded that it was only a matter of

time before all public accommodations were desegregated. And the propor-

tion of Southern respondents who felt this way continued to rise in 1962.

This was especially true in border states such as Missouri, Kentucky, and

Maryland, where two-party political dynamics and racial demographics pro-

moted a more open atmosphere, and where both school desegregation and

black voting had proceeded beyond the stage of tokenism. But even in the

so-called Rim South states of Florida, Texas, and Arkansas, as well as in the

Upper South states of Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee—all states

where the dual school system was still intact and black voting was still rare—

Epilogue: Glory Bound 501

the Freedom Rides failed to produce the kind of backlash that forestalled

progress. In South Carolina, a state often accorded Deep South status, the

situation was less promising, especially in communities such as Rock Hill

and Winnsboro, where the Freedom Riders had encountered stiff resistance

in 1961. Yet, in general, the Palmetto State did not live up to its longstanding

reputation for sectionalist defiance. Movement activity in the state quick-

ened noticeably in 1962, as Jim McCain spearheaded an ambitious Voter

Education Project that registered 3,700 new black voters by the end of the

year. And both CORE and an increasingly active NAACP led by state field

secretary I. DeQuincey Newman organized a series of desegregation cam-

paigns that extracted significant gains without provoking widespread vio-

lence. While segregated institutions remained in force throughout most of

the state, the tone of public reaction and political discourse suggested some-

thing less than massive resistance.

26

The ability of McCain to operate in the open, despite his close associa-

tion with the Freedom Rides, and his continuing success in recruiting local

volunteers were welcome signs that encouraged CORE to expand its op-

erations in neighboring states, especially in North Carolina. During the

spring of 1962 the organization launched an ambitious campaign to create

“Freedom Highways” all along the southeastern seabord. Conceived as “a

natural southward extension of the Route 40” campaign,” which was still

active in Maryland, the Freedom Highways project targeted the popular but

A Maryland policeman and a restaurant proprietor confront Bayard Rustin during the

1962 Route 40 desegregation campaign. (Photograph by Bob Adelman, Magnum)

502 Freedom Riders

segregated Howard Johnson’s restaurants that dotted tourist routes from Bal-

timore to Miami. The campaign attracted a number of veteran activists, in-

cluding Jim Peck and Bayard Rustin, and by the end of May almost all of the

chain’s restaurants in Maryland and Florida had capitulated to CORE’s pres-

sure. Some locally owned franchises in other states resisted, however, prompt-

ing the organization to refine its strategy. Concentrating its efforts on North

Carolina, CORE dispatched field secretaries and former Freedom Riders

Ben Cox and Jerome Smith to the state to organize local chapters and mobi-

lize demonstrators in several key cities. Aided by many of the same local

activists who had hosted and supported the original Freedom Riders in May

1961, Cox and Smith developed strong CORE chapters in Greensboro, Ra-

leigh, and Burlington that initiated mass protests at several Howard Johnson’s

restaurants in August and September.

During four weeks of sit-ins and marches, more than two thousand dem-

onstrators participated and nearly one hundred were arrested. After an initial

round of arrests in Durham, Farmer, Peck, and Roy Wilkins flew in from

New York to lead a protest march, and at a subsequent march in Statesville,

Farmer and a local minister spoke to more than six hundred supporters in the

town square amidst “a thick fog of insecticide laid by the police.” In other

communities, the police were more restrained, and Peck—whose gripping

memoir Freedom Ride would soon be published by Harper and Row—came

away from the Durham march with the sense that both official intimidation

and white resistance were diminishing. Comparing his recent experience with

his first visit to Durham in 1947, he concluded that “this type of protest in a

place like Durham would have been inconceivable 15 years ago.” Perhaps

even more telling was the successful desegregation of more than half of the

state’s Howard Johnson’s restaurants by the end of August, along with Gov-

ernor Terry Sanford’s willingness to meet with Farmer and other movement

leaders to discuss ways of accelerating the pace of desegregation in North

Carolina. Desegregating the remaining restaurants would require eight more

months of negotiation and mass protest. But, as Peck observed, North Caro-

lina officials, unlike their Mississippi and Alabama counterparts, seemed to

be embracing a more tolerant attitude toward dissent.

27

This trend was also evident in Tennessee, where two liberal Democratic

senators, Estes Kefauver and Albert Gore, maintained close ties with the

Kennedy administration, and where, for the most part, segregationist fer-

ment was on the wane following the Freedom Rides. Unlike its neighbors to

the south, Tennessee boasted a highly competitive two-party political sys-

tem that inhibited racial demagoguery and extremist rhetoric. And, despite

the Nashville Movement’s prominent role in the Freedom Rides, relatively

few white Tennesseans exhibited the kind of reactionary fervor that gripped

much of Mississippi and Alabama. Although many communities, particularly

in the lowlands of western and central Tennessee, retained a strong commit-

ment to racial separation, the state as a whole lacked ideological consistency.

Epilogue: Glory Bound 503

In late January 1962 the noted black journalist Carl Rowan, who had re-

cently accepted an appointment as a deputy assistant secretary of state, was

refused service at a Memphis airport restaurant, but thoroughly desegregated

transit facilities were the norm almost everywhere else. Aside from a few

marginal Klansmen, there was no public interest in challenging or defying

the ICC order, and the overall tenor of race relations was noticeably calmer

in Tennessee than in many areas of the South.

This relative calm, as proud Tennessee moderates liked to point out,

was partly a function of reasoned political dialogue and interracial coopera-

tion, but it also reflected the weakness of the movement in Tennessee. In the

western counties of Fayette and Haygood, the bitter three-year-old voter

registration struggle that had attracted national attention and legal interven-

tion by the Justice Department continued with no resolution in sight. But

outside of Nashville and the nearby town of Lebanon, where CORE estab-

lished a small chapter in July, there was little civil rights activity in the state

in 1962. Even the Nashville Movement was only a shadow of what it had

been earlier in the decade. Despite the best efforts of John Lewis, who re-

turned to the city in September 1961 to enroll at Fisk, the number of local

students willing to engage in nonviolent direct action fell below the level of a

true mass movement; and the student central committee never quite regained

its momentum, even after Lewis’s former American Baptist Theological Semi-

nary roommate, Bernard Lafayette, joined him at Fisk in the winter of 1962.

Bill Harbour and Fred Leonard and several other former Tennessee State

students remained active, but following the collective expulsion of the Ten-

nessee State Freedom Riders the campus had ceased to be a reliable source of

nonviolent foot soldiers.

At the same time, the Nashville student movement was becoming a vic-

tim of its own success. Not only had partial victory bred a measure of com-

placency and dispelled a messianic sense of urgency in the city recently dubbed

the “Best City in the South for Negroes” by Jet magazine, but the central

committee had turned out to be a training ground for regional leadership.

The Bevels, Lester McKinnie, and others had long since moved on to con-

tinue the struggle in other parts of the South, and by the end of 1962 Lafayette

was also gone, having agreed to lead a SNCC voting rights initiative in Selma.

Even Lewis spent the summer of 1962 as a SNCC organizer in Cairo, Illi-

nois, and after his election as SNCC national chairman in June 1963, he too

moved on, relocating in Atlanta, where voters would elect him to Congress

twenty-three years later.

28

LADEN WITH IRONY, the situation in Tennessee was emblematic of the non-

violent movement’s dilemma in the wake of the Freedom Rides. The Rides

had led to the desegregation of Jim Crow transit facilities, but the meaning

of the victory was subject to a wide range of interpretation and manipulation,

both inside and outside the movement. For a majority of the Freedom Riders,

504 Freedom Riders

achieving compliance with the Morgan and Boynton decisions was essentially

a means to an end rather than an end in itself, a way of exercising rights of

citizenship that would not only challenge the status quo but also reveal the

stifling limitations of gradualist reformism. By demonstrating the moral power

of nonviolence as well as the resolute determination of ordinary citizens to

achieve simple justice, the Riders hoped to transform the civil rights move-

ment into a broad-based and insistent freedom struggle. For some, nothing

short of Jim Lawson’s “beloved community” would do, but even those activ-

ists who set their sights on a less revolutionary goal saw the Rides as a pro-

genitor of radical and accelerated change.

Many other observers, however, viewed the Freedom Riders’ victory quite

differently, either as an anomaly or as confirmation that governmentally ad-

ministered gradualism was the key to civil order and social progress. Empha-

sizing the Kennedy’s administration’s capacity to respond to the crisis, while

downplaying the catalyzing role of the Freedom Riders themselves, the main-

stream viewpoint tended to focus on the ICC order, not on the provoca-

tions that brought it about. Predictably, this perspective became stronger

over time. While detailed memories of the Rides inevitably faded, the ef-

fects of the order became clearer and more tangible, especially after the offi-

cial validation of the order’s importance by administration and supporting

media sources.

Reformulated to fit both the general myths of reformist politics and the

more specific conditions of an election year, the story of the Freedom Rides

became the story of transit desegregation in 1962. Among nonviolent activ-

ists and in some black communities, particularly along the route of the Free-

dom Rides, there was consternation that recent history was being recast to

serve the interests of a centrist administration. But most Americans, then

and later, had little appreciation for the clash between movement and estab-

lishment lore. Even though it had great difficulty resolving the Freedom

Rider crisis, the Kennedy administration demonstrated its ability to put a

self-serving spin on the Rides as early as May 1961, during the immediate

aftermath of the Anniston and Birmingham riots. And this effort continued

off and on for the better part of a year. In December an official press release

summarizing “the Administration’s accomplishments in the civil rights field”

hailed the ICC order and the government’s role in bringing about “substan-

tial progress” in transit desegregation but barely mentioned the Freedom

Riders. Indeed, at a press conference held in January 1962, the president

failed to mention the Freedom Riders at all in a statement citing the order as

one of three significant civil rights achievements accomplished during his

first year in office.

Whether this particular statement represented a failure of understand-

ing or a deliberate misappropriation of credit is unclear, but one suspects

that such slights often reflected a purposeful political or ideological strategy.

For a variety of reasons, administration officials did not want to encourage or

Epilogue: Glory Bound 505

legitimize direct action, especially by naive and radical provocateurs who

operated outside the bounds of political consensus. Later in the decade, gov-

ernment authorities would freely acknowledge the heroism and sacrifices of

the Freedom Riders. And even the original architects of the dismissive inter-

pretation of the Freedom Rides, including Burke Marshall and Robert

Kennedy, eventually admitted that the crisis provided the federal govern-

ment with an “education” and a much-needed push toward constitutional

enforcement. But as long as the Kennedys were in power, there would be no

White House receptions, or even public statements, honoring the risk-tak-

ers who had forced a reluctant administration to act.

29

This policy was grounded in practical politics, and administration lead-

ers thought they had a strong electoral rationale for distancing themselves

from the Freedom Riders, even though liberal contemporaries and later his-

torians and political scientists accused them of excessive timidity. Operating

without a strong public mandate or a solid Democratic majority in Congress

and facing the prospect of losing congressional seats to the Republicans in

the fall 1962 elections, the Kennedys calculated that they could ill afford to

alienate powerful conservatives within their own party. As early as July 1961

one aide, after concluding that “the dynamics both here and abroad compel-

ling desegregation are accelerating,” advised that providing “leadership for

those forces and to moderate Southern difficulties without destroying the

Congressional coalition at mid-term is the nub of the problem.” This prob-

lem loomed even larger in the wake of the Freedom Rides and the ICC or-

der. After disappointing the civil rights community in January 1962 with the

announcement that he had no immediate plans to “put forward . . . major

civil rights legislation,” the president tried to assuage the feelings of blacks

and liberals by letting it be known that he intended to appoint a black man,

Robert Weaver, as the first secretary of a new Department of Urban Affairs.

But this gesture backfired when a conservative bipartisan coalition promptly

rejected the bill authorizing the new department.

At the same time, Kennedy endorsed a moderately progressive bill pro-

hibiting the use of literacy tests for federal election registration, but even this

fairly innocuous challenge to the political status quo in the white South went

down to defeat in May. By summer he and other chastened Northern Demo-

crats were in full retreat on legislative issues related to civil rights, and the

elevated priority of avoiding sectional disharmony remained in force until

well after the fall elections sustained a Democratic majority in both houses of

Congress. Only the federal intervention at the University of Mississippi in

September interrupted this strategy, but for many white Southerners this

anomaly was an acceptable response to violent extremism.

30

Justified or not, political considerations alone cannot explain the

administration’s rude treatment of the Freedom Riders, or its continuing

inattention to pressing civil rights matters. Ideological commitments also

dictated an official postmortem that reduced the Riders to bit players in a