Adelaar Willem, Muysken Pieter. The languages of the Andes

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

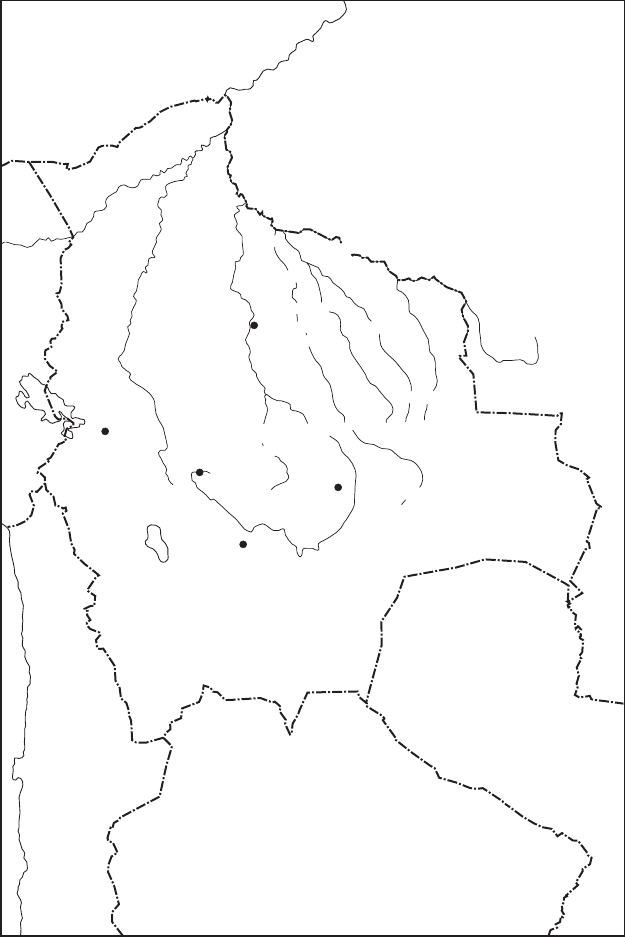

414 4 Languages of the eastern slopes

ITONAMA

JORÁ

CAYUVAVA

CANICHANA

CHÁCOBO

MORÉ

ESE'EJJA

PACAGUARA

CAVINEÑA

REYESANO

MOVIMA

SIRIONÓ

BAURE

Trinidad

MOJO

CHIMANE

MOSETÉN

YURACARÉ

YUQUI

Cochabamba

Santa Cruz

Sucre

CHIQUITANO

GUARAYO

AYOREO

CHANÉ

CHIRIGUANO

MATACO

TAPIETÉ

PARAGUAY

ARGENTINA

BOLIVIA

La Paz

Lake

Titicaca

LECO

TACANA

TOROMONA

ARAONA

BRAZIL

C

H

I

L

E

P

E

R

U

B

e

n

i

R

.

M

a

d

r

e

d

e

D

i

o

s

R

.

M

a

m

o

r

é

R.

G

u

a

p

o

r

é

R

.

S

a

n

M

i

g

u

e

l

R

.

P

A

U

S

E

R

N

A

P

a

n

ag

u

á

R

.

Map 9 Eastern lowland languages: Bolivia

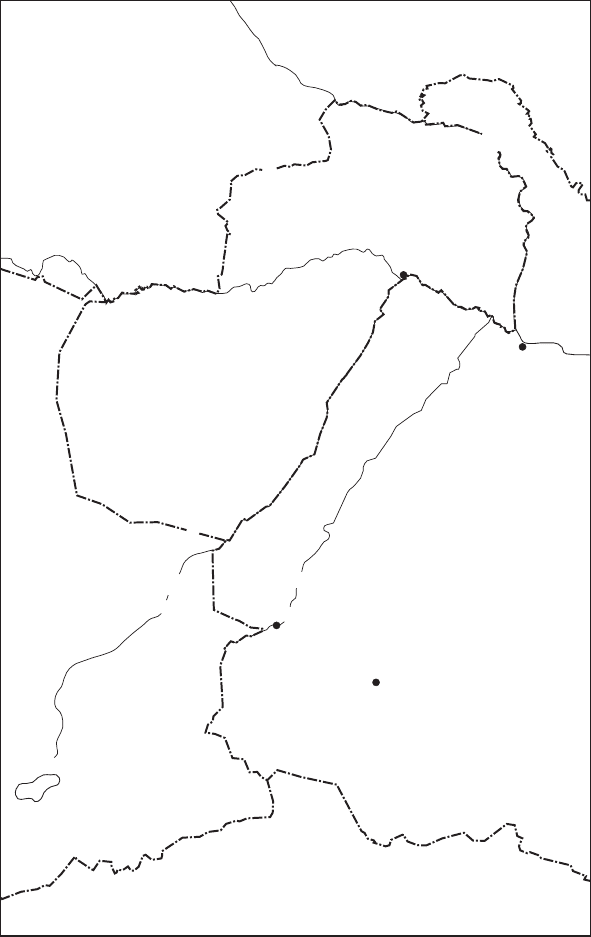

BOLIVIA

P ARAGUAY

Orán

Salta

ARGENTINA

Resistencia

Asunción

SANAPANÁ

MBYÁ

BRAZIL

C

H

I

L

E

P

a

ra

n

á

R

.

MBYÁ

ACHÉ

MAKÁ

CHIRIPÁ

P

a

r

a

g

u

a

y

R

.

EMOK

TOBA

TOBA

G

U

A

R

A

N

Í

VILELA

MAKÁ

B

e

r

m

e

j

o

R

.

P

i

l

c

om

a

y

o

R

.

P

I

L

A

G

Á

CHOROTE

CHOROTE

M

A

T

A

C

O

C

H

I

R

I

G

U

A

N

O

LENGUA

CHULUPÍ-

ASHLUSHLAY

ANGAITÉ

PAI-TAVYTERÃ

GUANÁ

TAPIETÉ

CHULUPÍ

C

H

I

R

I

G

U

A

N

O

M

A

T

A

C

O

AYOREO

CHAMACOCO

TOBA-

MASCOY

M

O

C

O

V

Í

˜

Map 10 Eastern lowland languages: the Chaco area

416 4 Languages of the eastern slopes

B. Grimes (1996) lists 111 documented languages for the area (excluding for the mo-

ment lowland varieties of Quechua, sign languages, Low German and Amazon Spanish).

Twenty-one languages were claimed to be extinct in 1992, some more may have disap-

peared as we write this, and more yet when this book comes out in print. The number

of languages listed is somewhat arbitrary in that it is difficult to say where two varieties

should be counted as dialects, and where as separate languages. The Ethnologue uses

both criteria of linguistic distinctiveness and of ethnic self-identification. We see no

reason not to follow these criteria, although in details we will diverge from the list of

languages given there.

In any case, it is clear we are dealing with large numbers of languages. ‘No other area

of South America has greater linguistic diversity’, Steward (1948: 507) writes. There

are a few larger language families represented in the area under consideration, a number

of language families with few identified members and numerous language isolates. We

will begin by presenting the major language families that are represented in the area,

and then turn to the numerous language isolates or languages which so far have not

been definitively classified. We have chosen four languages for a more detailed sketch:

the Jivaroan language Shuar from the Ecuadorian–Peruvian border area, the almost

extinct isolate Chol´on from the Andean foothills in northern Peru, Arawakan Yanesha

(Amuesha) further to the south, and the Bolivian language isolate Chiquitano. For all

languages sufficient information is available to gain some idea of the language, but no

recent and easily accessible detailed description in English.

It is difficult to convey to the reader the feeling of devastation and loss one has

when reading about the cultures and languages of the eastern slopes and the Amazon.

Although a sizeable portion of the original ethnic groups is still in existence, in some

form or another, their way of life has changed enormously. Since the armies of Inca

Tupac Yupanqui (1473–92) tried to conquer Madre de Dios and more northern lowland

regions, the vast but ecologically delicate Amazon basin has been under constant

siege from the highlands, with greater and greater success. From the 1540s onwards

Jesuits, Franciscans and Dominicans founded missions, and tried to ‘reduce’ the

Indians, nomadic or dispersed, into ordered settlements on the European model. In

the reducciones, ‘reductions’, as the Spanish friars called the settlements, different Indian

nations were mixed; sometimes new groups emerged. The greater concentration lead to

greater ease of ‘benign’ exploitation by the missionaries, but also to greater vulnerabil-

ity to epidemics; successive waves of smallpox for example in 1660, 1669, 1756 and

1762 decimated many groups (Phelan 1967: 47). In 1768 only 500 Chamicuro survived

a smallpox epidemic on the Huallaga river (Chirif and Mora 1977); another group that

suffered greatly from the epidemics are the Z´aparo. A. C. Taylor (1999: 240) claims that

‘the Indian societies of the central selva and further south were in fact infinitely better

able to resist the colonist missionary onslaught than those in the reducciones,evento

4 Languages of the eastern slopes 417

the point of being able, between 1742 and 1770, to clear the region of all non-natives’. The

Franciscans in that area in the early stages weakened indigenous societies less

than the Jesuits, because they tended to keep the groups contacted much more isolated

than the Jesuits.

Some groups were also subject to raids by other Indians. In the eighteenth century the

Arawakan Piro sold Machiguenga (also Arawakan) women and children on the market in

the Spanish hacienda Santa Rosa in Rosalino. The Piro and the Shipibo–Conibo (Pano)

enslaved many Amahuaca as well. Other Indian nations suffered from the colonial wars

between the Portuguese and the Spanish. The Omagua, who fell victim to Portuguese

slave-raiders, went from 15,000 to 7,000 in the forty years after 1641 (Chirif and Mora

1977). Later strife between the Peruvian and Colombian armies affected the Huitoto

Murui.

All these earlier assaults on their physical and cultural integrity pale, however, when

compared to the effects of the rubber boom in the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries (Fawcett 1953; Taussig 1987). Rubber traders and companies enslaved many

Indians, and resettled entire groups. The number of deaths is staggering. The Huitoto

Murui went from 50,000 to 7,000 in the first decade of this century, the Bora from 15,000

in 1915 (Whiffen 1915) to 427 in 1940, and of the thousands of Omagua only 120–50

were left in 1925. Other groups gravely affected by the rubber boom are the Andoque,

the Capanahua, the Amarakaeri and the Ese

ejja. After 1850 the Peruvian Corporation

enslaved many Campa and Yanesha

(Amuesha) on the rivers Ene and Peren´e. Many

Chamicuro were dislocated, transported to the Yavar´ı and Napo rivers and to Brazil.

Since this period groups have managed for a considerable period at best to remain

stable or increase slightly in number. In the modern era, Andean governments have often

thought that the ‘empty’ spaces in the lowlands would be able to absorb the overflow from

the highlands, and promoted resettlement and ‘colonisation’ in the traditional Indian ter-

ritories. Mineral, logging and cattle-breeding companies have gained large concessions

and employ the local Indians in highly unfavourable conditions. Adventurous highland

settlers have profited from the isolation of many regions to establish themselves as patr´on

and recreate conditions of virtual slavery through artificial indebtedness, forced barter

and plain violence. There are many cases documented where the Indians, part of a hunt-

ing/extraction economy, depend on the outsiders and are for example forced to supply

afixed number of skins. It is reported that the Amarakaeri work for outsiders looking

for gold (Gray 1986). For the dependency of the Yagua on tourism and other external

forces see Chaumeil (1984).

In some areas these conditions have long persisted, for instance, in the area of Atalaya.

Now tribal groups have gained some rights to their territories there (Garc´ıa, Hvalkof and

Gray 1998). It is one of the great challenges of our era to create the conditions under

which cultural pluralism can thrive, when no physical means of refuge is left.

418 4 Languages of the eastern slopes

A. C. Taylor (1999: 204–5) argues that the locations of individual groups have not

changed a great deal, but other changes are massive. In the sixteenth century the

Amerindian societies were much more diversified sociologically than they are now.

There were a number of highly Incanised tribes, such as the upland Jivaroans (cf. section

3.9.1), but also J´ıvaro who lived in small bands in the jungle. There were groups like

the Z´aparo and interfluvial Pano that lived in small units and had no complex social

structure next to large riverside groups like the Conibo and Omagua.

A general issue of considerable interest that needs careful study is the role of the

respective sign languages in the Amazon basin. Nordenski¨old (1912: 315–21) reports

for the Gran Chaco, the border area between Bolivia and Paraguay, that within the mestizo

Spanish communities the deaf had a marginal position while in the Indian communities

they were fully integrated. The reason is the very different status of the respective sign

languages. The Tapiet´e, the example he uses, obligatorily express numbers and measures

through signs, and in their narratives, sign accompanies the spoken word continuously.

All members of the group can use sign with the deaf, and hearing Tapiet´e will often

use sign language among themselves, for example when they want to communicate

silently across a distance. Not all travellers, collectors and researchers were as careful

and unbiased as Nordenski¨old, who provides five pages of description of the Tapiet´e

signs, but reports of gestural communication abound. The reason we cannot deal with

this issue any further is lack of systematic study.

4.1 The Pano–Tacanan languages

The Pano–Tacanan language family is mostly spoken in the Peruvian lowlands, and to

a lesser extent in contiguous areas of Brazil and Bolivia. In Bolivia, Panoan languages

include Ch´acobo, Pacaguara and Yaminahua; and Tacanan languages: Araona, Cavine˜na,

Ese

ejja or Huarayo, Reyesano (a language virtually extinct), Tacana and Toromona.

The Tacanan branch is represented in Peru by Ese

ejja or Huarayo speakers on either

side of the Bolivian border.

The Panoan branch is spread out throughout the eastern Peruvian lowlands and, in

particular, near the Ucayali river basin, with extensions along the Brazilian border both

in the northern department of Loreto and the southern departments of Ucayali and

Madre de Dios. As d’Ans (1970) and Kensinger (1985) explain, there is no consensus

as to which Panoan languages have to be distinguished. Shell and Wise (1971) observe

that speakers of different Panoan languages may partly understand each other but that

Cashibo is not intelligible to speakers of other Panoan languages. Wise (1985) men-

tions the following extant Panoan languages in Peru: Amahuaca, Capanahua, Cashibo–

Cacataibo, Cashinahua, Cujare˜no, Isconahua, Mayoruna, Morunahua, Parquenahua or

Nahua, Pisabo, Sharanahua, Shipibo–Conibo–Shetebo and Yaminahua. The Ethnologue

adds Mayo, which is reported extinct by Wise (1985). Varese (1983) also mentions

4.1 The Pano-Tacanan languages 419

Marinahua and Mastanahua. Kensinger (1985) reports that they constitute a mixed group

with the Sharanahua. Chirif and Mora (1977) mention a small group called Chandinahua.

Amahuaca, Cashinahua, Mayoruna and Yaminahua are spoken in Brazil as well.

Many Panoan groups were contacted in the eighteenth century. The Cashibo were first

visited by missionaries in 1757. Around 1870 the Pachitea river Cashibo were subject

to attacks by the Setebo and the Conibo (Chirif and Mora 1977).

The Panoan languages are all closely related, and have been the subject of a number

of comparative studies by d’Ans (1970), Kensinger (1985), Shell and Wise (1971) and

Wise (1985). In Key (1968) and Girard (1971) the Tacanan languages are compared

phonologically and cognate sets are given for this subfamily, some members of which

appear to be rather closely related. These sources also present convincing phonological

evidence for the link between the Tacanan and the Panoan branches. Girard (1971: 4, 145)

stresses the puzzling fact that phonological changes in lexical roots have been limited

within both the Panoan and Tacanan branches, but that morphological changes, partic-

ularly in the ‘root extensions’, have been radical. This pattern points to an interesting

early contact phase in these language groups.

For many of the language groups in the monta˜na little is known about their history.

Lathrap (1970) speculates that the split in the Panoan groups resulted from demographic

pressures. While all Panoan groups presumably originate from the Cumancaya culture

(around AD 1000), we now find the Shipibo–Conibo being settled along the Ucayali

river basin, with an enriched culture (which also includes culture elements borrowed

from the Tup´ıan Cocama). The Cashibo have been pushed into forest regions to the west

and the Amahuaca, Remo and Mayoruna into areas to the east, and their present culture

(as far as ceramics and other visual manifestations is concerned) is an impoverished

version of that found a millennium ago.

As far as information is available, the Panoan and Tacanan languages appear to be all

SOV. From Loos’s (1969) grammatical analysis of Capanahua it becomes clear that it

has postpositions and prenominal possessors. The position of the adjectives and other

modifiers is less clear: both prenominal and postnominal adjectives are mentioned. There

appears to be a validator or mood particle (glossed ‘affirmative’ here) in surface second

position, which can be preceded by the subject, the object, an adverb or even the untensed

verb.

(1) a. mani ta how-ti-ʔʔ-ki

banana AF ripe-TF-PN-AF

‘The bananas are ripening.’

(Loos 1969: 91)

b. mani ta ʔʔn his-i

banana AF 1.SG see-PN

‘I see bananas.’

(Loos 1969: 91)

420 4 Languages of the eastern slopes

c. baʔʔkiˇstakoka ka-no-ˇs

.

iʔʔi-ki

tomorrow AF uncle go-F.EU-IU-AF

‘Uncle will go tomorrow.’

(Loos 1969: 91)

d. bana ta ʔʔn ha-ipi-ki

plant AF 1.SG do-RE-AF

‘I planted.’

(Loos 1969: 91)

That the mood particle or validator occurs after the true first element of the clause

becomes evident when an (emphatic) first- or second-person pronoun is placed in initial

position. It is repeated in the clause, and thus it seems that the emphatic pronoun is

left-dislocated:

(2) mia taʔʔ min ʔʔani-ki

2.SG.EM AF 2.SG big-AF

‘YOU are big.’

(Loos 1969: 92)

The relation between ta(

ʔ

) and the particle -ki,which also has affirmative value, needs

further study. In the present tense -ki is obligatory with third-person subjects, but not

with first- and second-person subjects. In other tenses -ki is found with all persons (Loos

and Loos 1998: 34).

A remarkable feature of Capanahua concerns recursive negation with ma of a deictic

pronoun:

(3) ha: ‘he’

ha:-ma ‘not he’

ha:-ma-ma ‘not not he’ (= he indeed)

ha:-ma-ma-ma ‘not not not he’ (= someone else)

(Loos 1969:41)

There is a set of adverbial subordinating suffixes (attached to the clause-final verb),

sensitive to the relation between the tenses of the adverbial clause and the main clause,

to possible coreference of the subjects (switch-reference), and to possible transitivity of

the matrix verb (Loos 1969: 67–77; Loos and Loos 1998: 660–3).

1

(4) -kin simultaneous action (‘while’)

same subject

-ton simultaneous action (‘while’)

subject of subordinate clause is object of main clause

1

The resemblance between some of the Capanahua suffixes and their counterparts in Chipaya is

striking (cf. section 3.6): Cap. -kin / Ch. -kan ‘simultaneous; same subject’; Cap. -ton / Ch. -tan

‘simultaneous and previous, respectively; different subjects’; Cap. -non / Ch. -nan ‘subsequent

and simultaneous, respectively; different subjects’.

4.1 The Pano-Tacanan languages 421

-ya simultaneous action (‘while’, ‘when’, ‘if’, ‘because’)

different subjects

-ʔʔaˇs

.

preceding action (‘after’, ‘when’, ‘if’, ‘because’)

same subject

matrix verb intransitive

-ˇs

.

on preceding action (‘after’, ‘when’, ‘if’, ‘because’)

same subject

matrix verb transitive

-noˇs

.

on subsequent action (‘in order to’)

same subject

-non subsequent action (‘so that’)

different subjects

A curious fact concerning switch-reference in Capanahua is that the subject of the matrix

verb in a switch-reference construction cannot be a full pronoun. The latter can only

occur in the subordinate clause, as shown by the contrast in (5):

(5) a.

∗

ka-ʔʔaˇs

.

ha: nokoti

go-SS 3.SG arrive

b. ha: ka-ʔʔaˇs

.

nokoti

3.SG go-SS arrive

‘Having gone he arrived.’

(Loos 1969: 88)

Often Capanahua utterances consist primarily of a verb with its suffixes. Verbs may be

marked as transitive with the (often causative) suffixes -ha, -n and -tan, and there is a

suffix -k

ʔ

t /-(

)

ʔ

t that makes a verb medial or reflexive in nature (Loos 1969: 143–7).

There is also an extensive set of tenses. According to Loos, both for the past and for the

future, a four-way distinction is made:

(6) remote past x > 6 months

6 months > x > 1 month

recent past 1 month > x > 1day

1day> x > present

present x = present

immediate future present < x < few hours

near future x = tonight, tomorrow morning

distant future tomorrow < x

remote future x = some time in the future

(Loos 1969: 28)

Valenzuela (2000a, b) has explored ergative splits in the Pano–Tacanan languages. Camp

(1985) shows how noun/pronoun contrasts, and among the personal pronouns, person

422 4 Languages of the eastern slopes

contrasts, determine ergative and absolutive case in Cavine˜na. When a third-person

subject interacts with a first- or second-person object, as in the independent clause in

(7), the third person is obligatorily ergative:

(7) ya-ce-ra hipe-etibe-ya-hu ta-ce-ra ya-ce isara-ca-k

w

are

1-D-E approach-on.way.back-PN-DS 3-D-E 1-D(A)

greet-arriving.object-RM

‘Asweapproached them, they greeted us.’

(Camp 1985: 44–5)

Similarly, when a second-person subject interacts with a first-person object, that second

person is obligatorily ergative:

(8) riya-ke wekaka mi-ra e-k

w

ana isara-nuka-wa

this-which day 2.SG-E 1-PL(A) greet-again-RE

‘Today you spoke to us again.’

(Camp 1985: 45)

Guillaume (2000) is currently studying Cavine˜na from the perspective of spatial deixis.

4.2 The Arawakan languages

The Arawakan language family, also referred to as Maipuran (David Payne 1991a), has a

wide distribution in many areas of Central and South America. A. C. Taylor (1999: 205)

observes that Arawakans lived in a fringe extending from the Pampas del Sacramento

in the central Peruvian forest area to the Bolivian llanos. This fringe was broken by

the Harakmbut and by Tacanan peoples. Taylor points at the variety in lifestyle among

the Arawak, which included monta˜na people (e.g. the Amuesha or Yanesha

), riverside

dwellers (e.g. the Piro), atomised small groups, such as the Machiguenga, and well-

organised chiefdoms, such as the Mojos. There was extensive trading between different

groups. Taylor also includes the Panatagua, an extinct group of central Peruvian monta˜na

dwellers among the Arawakans. However, the linguistic affiliation of the Panatagua has

never been established with certainty.

The Arawak family is represented in Bolivia by the Mojo language, which is split

into two subgroups identified by their ancient mission names, Ignaciano and Trinitario

(Olza Zubiri et al. 2002). A second Arawakan language is Baure. David Payne (1991b)

has shown that Apolista or Lapachu, a nearly extinct language which has been reported

by Monta˜no Arag´on (1987–9) as still spoken, should also be classified as Arawakan.

The Chan´e, another Arawakan group, subjugated to the Tupi–Guaran´ı Chiriguano of the

Argentinian–Bolivian border area, preserved its language until the twentieth century.

Some smaller Arawakan groups (Paunaca, etc.) were incorporated by the Chiquitano.

Very close to the Andes in Peru we find Campa, Machiguenga and Yanesha

. The

Yanesha

have a history of frequent contacts with members of other groups; they live

4.2 The Arawakan languages 423

Table 4.1 The relationship between the Arawakan languages of the pre-Andean area

(based on Payne 1991a, b)

Northern Apolista Apolista

Baniva–Yavitero Baniva del Guain´ıa, Yavitero

Caribbean Guajiro, Paraujano

North Amazon Achagua, Cabiyar´ı, Curripaco, Maipure, Piapoco, Res´ıgaro,

Tariana, Yucuna

Western Amuesha Amuesha

Chamicuro Chamicuro

Central Parecis-Saraveca Saraveca

Southern Bolivia-Paran´a Baure, Guan´a (Chan´e), Mojo (Ignaciano, Trinitario)

Campa Ash´eninca, Machiguenga

Piro–Apurin˜a Piro, I˜napari

near the Cerro de la Sal, a site of traditional pilgrimages and trade. From 1635 onward

they were in contact with the Franciscans, and in 1742 there was the rebellion of Juan

Santos Atahuallpa, which led to the chasing away of the missions (Varese 1968). In 1881

the Franciscans returned. Taylor (1999: 241) argues that the Campa and Yanesha

were

less dependent on the highlands for metal tools because they had their own forges.

Campa is subdivided into several subgroups, the largest being called Ash´aninca and

Ash´eninca. Chirif and Mora (1977) mention a small group split off from the Machiguenga

called Kugapakori or Pucapacuri. A fourth Arawakan language in the southeastern low-

land is Piro, described by Matteson (1965). Campa and Piro are spoken in Brazil as well.

The remaining Arawakan languages in eastern Peru are I˜napari (in Madre de Dios),

Chamicuro and Res´ıgaro (both in Loreto). The latter two have also undergone profound

phonological change. Speakers of Res´ıgaro live near the Bora and Huitoto along the

Colombian border. There are no Arawakan languages spoken in Ecuador.

The Arawakan language family is one of the best-studied families in the area. Partly

based on earlier work of Wise and other scholars, David Payne (1991a) has managed

to reconstruct a large number of features of this language family, and put its internal

classification on a sounder footing. For the area under consideration the relationship

between the different Arawakan languages is as in table 4.1. This is a fairly conservative

grouping. It may be that southern and western Arawakan are closer than is apparent from

this classification.

David Payne speculates that Proto-Arawakan was highly agglutinative, with a set of

person prefixes (both on nouns and verbs) and a third-person-singular gender distinction.

There are also noun class suffixes, and a number of valency-changing verbal elements are

suffixal. We will not enter into a detailed discussion here of the typological characteristics

of the Arawakan languages, referring the reader to David Payne (1991a) and the work

cited there, and for syntactic properties to Derbyshire (1986) and Wise (1986). Wise