Adelaar Willem, Muysken Pieter. The languages of the Andes

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

394 3 The Inca Sphere

in modern Imbabura Quechua is the use of a labial fricative f (from earlier Quechua

*p

h

; cf. section 3.2.5). Place names with characteristic stems and endings, as well as a

fair number of family names mentioned in the colonial documents, constitute evidence

of the past existence of Cara and give an impression of its phonology. Some endings

(e.g. -mued, -pud) are shared with Pasto, suggesting some kind of relationship between

the two languages. River names in -p´ı/-b´ı (e.g. Calap´ı, Chulxab´ı) suggest a connection

with the Barbacoan languages, where this element has the meaning of ‘water’ or ‘river’.

PazyMi˜no (1941a) favours the view that Cara was related to Tsafiki (cf. section 2.17).

Among the most frequent endings in place names is -qu´ı [k´ı] (compare Pasto -quer), for

instance, in Cochasqu´ı, Pomasqu´ı and Tuntaqu´ı. Caillavet identifies further toponymical

elements, such as -puela/-buela ‘field’, -pigal ‘earth ridge’ and -yasel ‘artificial mound

(locally known as tola)’. A recurrent element in personal names is ango, identified as

‘lord’. It is found, for instance, in the name of the sixteenth-century cacique of Otavalo,

Otavalango,but it also occurs by itself (Caillavet 2000: 28). Unfortunately, there are

hardly any Cara forms of which the meaning is known with certainty. One of the very

few cases is the element -piro/-biro, identified as ‘lake’ or ‘pond’ in the Relaciones

geogr´aficas,which is found in the place names Pimampiro and Tumbabiro (Jim´enez de

la Espada 1965, II: 236, 248).

186

PazyMi˜no (1961a) refers to an (extinct) Cara population on the Ecuadorian coast, near

Car´aquez bay (Manab´ı). Presumably, this idea was inspired by Velasco’s controversial

account of the Cara or Scyri rulers, who would have invaded the highlands from the

coast in pre-Inca times (Velasco 1789). Regardless of the question whether Velasco’s

account has any historical basis, there is no reason to assume that the Cara language

as we know it from toponymy and historical sources was the product of such a coastal

invasion.

The Panzaleo language owes its name to the Inca settlement of the same name,

situated not far from Quito (cf. Salomon 1986). The Panzaleo area extended from Quito

in the north to the town of Mocha in the south, covering the provinces of Cotopaxi

and Tungurahua, as well as the southern part of Pichincha. The main centres in the

area, apart from Quito itself, are Ambato and Latacunga. The Panzaleo area may have

been the first in the Ecuadorian highlands to become thoroughly Quechuanised. Typical

toponymical endings of the Panzaleo area are -(h)al´o (Pilal´o, Mulahal´o), -leo (Tisaleo,

Pelileo) and -lagua/-ragua (Cutuglagua, Tunguragua). The possibility that the original

language of the Quijos Indians, an ethnic group inhabiting the Andean foothills in the

western part of the province of Napo, was actually a variety of Panzaleo (as suggested

by Cieza de Le´on) is discussed in Jij´on y Caama˜no (1940: 289–95). The evidence is not

186

Translated as ‘great lake’ and ‘bird lake’, respectively. Note, however, that pim´an means ‘bridge’

in Tsafiki (Moore 1962).

3.9 Extinct and poorly documented languages 395

conclusive. Loukotka (1968) in his classification presents Panzaleo as related to P´aez

(see section 2.15). One of the sources for this view is Jij´on y Caama˜no (1940: 395–6),

who recognises that the evidence is weak and adds that any observed similarities, when

valid at all, may be attributed to contact.

Puruh´a or Puruguay was once the dominant language in the present-day province of

Chimborazo, except in its southernmost section of Alaus´ı and Chunchi, where Puruh´a

overlapped with neighbouring Ca˜nar. Jij´on y Caama˜no (1940: 417) leaves open the

possibility of an extension into the Chimbos area further west (province of Bol´ıvar),

but this idea is not accepted by Paz y Mi˜no (1942). The main centre of the former

Puruh´a area is Riobamba. In spite of this strategic position, the amount of information

on the language that has been preserved is disappointingly small. A late seventeenth-

century grammar is reported lost. Modern Puruh´a descendants now generally speak

Quechua.

Family names frequently end in -cela or in -lema. Examples are Duchicela, the lineage

of Atahuallpa’s mother, reportedly of Puruh´a descent (Velasco 1789), and Daquilema,

the name of a nineteenth-century rebel. Frequent endings of Puruh´a place names are -shi

(e.g. Pilligshi), -tus (e.g. Guasunt´us), -bug (e.g. Tulubug). More complex endings are

-cahuan, -calpi and -tactu. Some of these elements occur in combination with Quechua

roots, as in Supaycahuan (Quechua supay ‘devil’).

Puruh´aisgenerally believed to be related to Ca˜nar. Nevertheless, the two languages

are kept distinctly apart in the colonial Spanish sources. Some phonological character-

istics not usually found in the languages further north are shared by Puruh´a and Ca˜nar,

for instance, the use of voiced stops in word-initial position. Another interesting com-

mon feature is the existence of a voiced palatal fricative [ˇz] (written zh), which is not

demonstrably a reflex of earlier l

y

(as it is in some Ecuadorian Quechua dialects). It is

found word-initially in Ca˜nar place names, e.g. Zhud (R. Howard, pers. comm.).

The Ca˜nar language was spoken in the Ecuadorian highlands, in the provincesof Ca˜nar

and Azuay, and in parts of southern Chimborazo (Alaus´ı). According to the Relaciones

geogr´aficas de Indias (Jim´enez de la Espada 1965, II: 279), it was also used in Saraguro

in the northern part of the province of Loja, in spite of the fact that the Indians of Saraguro

were hostile to the Ca˜nar people further north. The Ca˜nar people played a crucial role

in the history of the Inca empire. After they had been conquered, the Incas embellished

their principal town of Tomebamba (Cuenca), which was then destroyed during the

civil war between Atahuallpa and Huascar. Many Ca˜nar people were sent to other parts

of the empire as mitimaes.Ca˜nar troops were sought out for police tasks and special

assignments, which they continued to perform under Spanish rule. The influence of

Quechua became particularly strong in the Ca˜nar region. Nevertheless, Ca˜nar continued

to be used during the colonial period until it was eventually replaced by Quechua. Today,

the main centres of the area are Cuenca, Azogues and Ca˜nar.

396 3 The Inca Sphere

Ca˜nar toponymy is highly characteristic and easier to recognise than that of Puruh´a.

Nevertheless, some endings (-pala, -pud,-bug, -shi) are shared by the two languages.

Luckily, the Relaciones geogr´aficas de Indias (Jim´enez de la Espada 1965, II: 265, 274–

5, 278, 280) are somewhat more informative about the meaning of Ca˜nar place and family

names than about those of other Ecuadorian highland languages. For instance, Leoquina

is translated as ‘snake in a lake’; Paute as ‘stone’; Peleusi (or Pueleusi)as‘yellow field’;

Pue¸car as ‘broom’. The Jubones river was called Tamalaycha or Tanmalanecha ‘river that

eats Indians’. A particularly interesting explanation concerns that of the plain in which the

city of Cuenca is situated. It was called Guapdondelic ‘large plain resembling heaven’.

This explanation allows an interpretation of quite a few place names, such as Bayandeleg,

Chordeleg, etc., which contain the element deleg ‘large plain’. Other place names contain

an element del (e.g. in Bayandel), which may have had a related meaning.

187

The most

frequent ending in place names is -cay [kay]. It has been interpreted as ‘water’ or ‘river’,

presumably because of its occurrence in river names, such as Saucay and Yanuncay

(Paz y Mi˜no 1961b). Other examples of endings occurring in Ca˜nar place names are

-copte (Chorocopte), -hui˜na (Catahui˜na), -turo (Molleturo), -zhuma (Guagualzhuma)

and -zol (Capzol). In addition to the original Ca˜nar place names, Quechua names are

also frequent. The ending -pamba ‘plain’, for instance, is more common than the native

-deleg.

In the sixteenth century the province of Loja was inhabited by a number of small ethnic

groups, which the Spaniards found difficult to control. The language they spoke was

known as Palta. Another language, Malacato,was spoken in a limited area south of the

town of Loja. Caillavet (2000: 233) also mentions an enclave of Ca˜nar speakers (Amboca)

situated to the northwest of that town. The Palta language had a wide distribution with

eastern outliers in the Zamora region and in the area of Ja´en (department of Cajamarca,

Peru).

188

Furthermore, its use may have extended to the area of Zaruma in the present-

day province of El Oro (Caillavet 2000: 216). Today the area, which no longer has a

substantial indigenous population, is mainly Hispanophone, with the exception of the

Quechua-speaking community of Saraguro in the north.

Several observations in the Relaciones geogr´aficas de Indias seem to indicate that the

languages of the area were closely related. It is generally believed that they belonged to

the Jivaroan language family. The only Palta words that were recorded are not from Loja,

but from a mountainous area called Xoroca not far from Ja´en (Jim´enez de la Espada

1965, III: 143). Of these four words (yum´e ‘water’, xeme ‘maize’, capal ‘fire’, let ‘fire-

wood’) the three first ones have been recognised as Jivaroan (Gnerre 1975). Many place

187

Bay´an is the name of a shrub.

188

On Ecuadorian maps the area of Ja´en is normally represented as a part of Ecuador, as a result

of the boundary conflict between the two countries.

3.9 Extinct and poorly documented languages 397

names in the Loja area end in -anga (Cariamanga), in -numa (Purunuma) or in -nam´a

(Cangonam´a, Gonzanam´a). Gnerre (1975) interprets the two latter endings as instances

of a Jivaroan locative case marker -num ∼ -nam,whereas Torero (1993a) offers a dif-

ferent interpretation by associating the ending -nam´a with Aguaruna nam´ak(a) ‘river’.

189

Similar elements are found in place names further east in the area of Zamora, where

the Relaciones geogr´aficas de Indias (Jim´enez de la Espada 1965, III: 136–42) mention

the existence of three other languages, Bolona, Rabona and Xiroa (possibly a variant

of J´ıvaro). For the Rabona language a certain number of vocabulary items, mainly

plant names, are listed. Torero (1993a) has identified some of these items as Candoshi

(e.g. chicxi ‘sapodilla’, Candoshi ˇc´ıˇci(ri)), but others are reminiscent of Aguaruna (e.g.

guapuxi ‘large guava’, Aguaruna w´ampuˇsik,Wipio Deicat 1996: 140). In spite of the

fact that Rivet (1934), Loukotka (1968) and Torero (1993a) have classified the Rabona

language as a member of the Candoshi family, we prefer to leave the matter undecided.

The affiliations of the Bolona language cannot be known for lack of data; it has been

classified as Jivaroan by Loukotka, whereas Torero suggests a connection with Ca˜nar

based on the geographical location of Bolona. Few of the communities of the Zamora

region mentioned in the early sources have survived, as much of the area was devastated

by intensive colonisation during the sixteenth century and by the subsequent Jivaroan

uprising (cf. Velasco 1789; Taylor 1999).

As a final addition to this discussion of the pre-Quechuan Ecuadorian highland lan-

guages, we may observe that, with the exception of the languages of Loja and possibly

also of Panzaleo, these languages share a number of distinctive elements that seem to

point at a common origin or a long period of interaction at the least. Examples of such

elements are words ending in the voiced consonants -d and -g, the ending -pud, and sylla-

bles with a complex labial onset (mue, pue, bue).

190

The fact that Pasto, with its probable

Barbacoan affinity, is one of the languages exhibiting these shared characteristics seems

to suggest a Barbacoan connection for this whole group of languages. Although far

from being proven, such a connection is more likely than the alleged relationship with

Mochica advocated by Jij´on y Caama˜no.

3.9.2 Northern Peru

In seventeenth-century sources the northern Peruvian Andes and coast are singled out

as a multilingual area that resisted Quechuanisation. Blas Valera, cited in Garcilaso de

189

The usual meaning of nam´ak(a) in the Jivaroan languages is ‘fish’, but in Aguaruna it has the

additional meaning of ‘river’.

190

Complex labial onsets are also found in Awa Pit (Curnow 1977: 34), where labial consonants

have a labial off-glide before the high central vowel ([p

w

], [m

w

]). Allophonic labial off-glides

following labial consonants have furthermore been encountered in Muisca (section 2.9.2), in

Shuar and in Yanesha

(chapter 4).

398 3 The Inca Sphere

la Vega (1609, Book 7, chapter 3), reports that the Quechua language was ‘unknown in

the administrative domain of Trujillo and other provinces belonging to the jurisdiction

of Quito’. The present situation and the little we know of past linguistic developments

in northern Peru give support to Valera’s impression. A number of non-Quechuan native

languages survived the conquest, giving way to Spanish often as late as in the nineteenth

and twentieth centuries. On the other hand, Quechua is not absent from the area. It has

survived in three distinct areas of northern Peru (see sections 3.1, 3.2.3), and it was

certainly more widely used in the sixteenth century (Rivet 1949: 2–3).

The near absence of documentation concerning the non-Quechuan languages of north-

ern Peru is striking. Except for the cases of Mochica and Chol´on, there are neither gram-

mars, nor dictionaries of these languages, not even the sort of religious texts that Spanish

priests considered necessary for evangelisation (cf. Adelaar 1999). An essential source

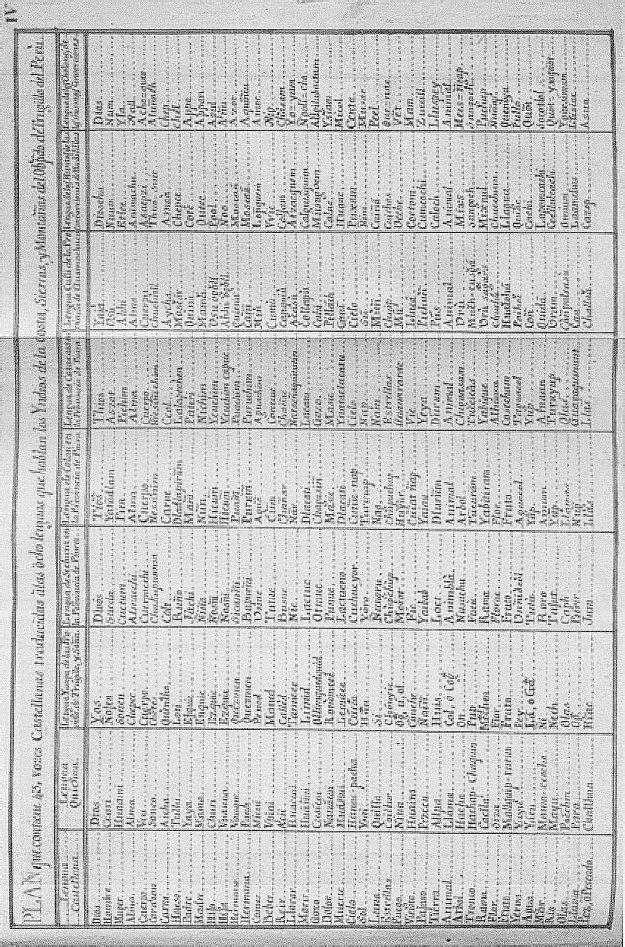

is Bishop Mart´ınez Compa˜n´on (1985 [1782–90]), who provided word lists of 43 items

each for nine languages spoken in his diocese (figure 1): Castilian (Spanish); Quechua;

the Yunga language of the provinces of Trujillo and Sa˜na (Mochica, see section 3.4);

the languages of Sechura, Col´an and Catacaos in the province of Piura (Sechura and

Tall´an); the Culli language of the province of Huamachuco; and the languages of the

Hivitos and Cholones of the Huailillas missions (Hibito and Chol´on, see section 4.11).

The most comprehensive attempt to reconstruct the colonial language map of northern

Peru is found in Torero (1986, 1989, 1993a). In this context a distinction should be

made between languages effectively mentioned in the sources and those whose former

existence is merely assumed on the basis of clusters of place and family names with

shared characteristics.

Among the well-attested languages are those of the coastal plain of the department of

Piura. One of these languages, known as Sechura, has been associated with the port of

Sechura at the mouth of the Piura river. A second language or language group, generally

kown as Tall´an,was found along the Chira river, including the coastal towns of Col´an and

Paita, and along the middle course of the Piura river, where it was spoken, among other

places, in the important indigenous community of Catacaos (near the town of Piura).

Ramos Cabredo (1950) provides an extensive list of place names, family names and

native words still in use in the Tall´an area. Typical endings for place names are -l´a,

-r´a (e.g. Narigual´a, Tangarar´a) and -ura (as in Nonura, Piura, Sechura). Family names

often end in -lup´u (Belup´u, Sirlup´u), in -bal´u∼-gual´u (Cutibal´u, Mangual´u), in -naqu´e

(Lequernaqu´e, Yamunaqu´e) and in -cherre (Pacherre, Tupucherre).

The word lists included in Mart´ınez Compa˜n´on exemplify the so-called ‘languages of

Col´an and Catacaos’, as well as ‘the language of Sechura’. The Col´an and Catacaos lists

represent closely related varieties, possibly dialects of the same language. A notable

difference between the two is that Catacaos often features a final element -chim on

nouns, whereas the Col´an equivalents only have a nasal (e.g. Catacaos puruchim, Col´an

Figure 1 Mart´ınez Compa˜

n´on’s word lists of 43 items each for nine languages spoken

in his diocese. Copyright

C

Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid

399

400 3 The Inca Sphere

puru

˜

m ‘sister’). Another interesting correspondence is phonological. Col´an syllable-

initial dl (possibly a voiced lateral affricate) is either d or l in Catacaos (e.g. Col´an

dlacati, Catacaos lacatu ‘to die’; Col´an dlur˜um, Catacaos durum ‘earth’).

191

Mart´ınez

Compa˜n´on’s Sechura list represents a separate language, because only about 30 per cent

of the vocabulary items show a similarity with either Col´an or Catacaos (Torero 1986:

532). Among the possible cognates we find Sechura lactuc, Col´an dlacati, Catacaos

lacatu ‘to die’; Sechura colt, Catacaos ccol ‘meat’; Sechura ˜nangru, Col´an nag ([na

ŋ

]?),

Catacaos nam ‘moon’; Sechura fic, Catacaos vic ‘wind’; Sechura yaibab, Col´an yaiau,

Catacaos yeya ‘bird’.

In 1863 Richard Spruce obtained from a native speaker in Piura a list of 38 words

which was later published by von Buchwald (1918). It has been identified as a sam-

ple of the Sechura language on the basis of a comparison with Mart´ınez Compa˜n´on’s

word lists (Torero 1986: 542). The available data suggest that Sechura was a suffixing

language. Kinship terms often contain the elements -ma and -˜ni (e.g. Spruce ˜nosma,

Mart´ınez Compa˜n´on ˜nos˜ni ‘son or daughter’), which were possibly possessive endings.

Sechura verbs as listed in Mart´ınez Compa˜n´on usually end in -(u)c (e.g. unuc ‘to eat’, nic

‘to cry’).

Rivet (1949) treats Sechura and Tall´an as a single language, which he calls Sek,

adopting the denominaton Sec introduced by Calancha (1638). This procedure is justly

rejected by Torero (1986). However, the possibility of a language family, including

both Sechura and Tall´an (Col´an–Catacaos), must remain open, considering the limited

number of vocabulary items that are available.

A possible extension of the Sechura language was found in the desert oasis of Olmos

in the present-day department of Lambayeque. When referring to the Sec language,

Calancha observed that the people of Olmos ‘change letters and endings’ (mudan letras

y finales). Although the name ‘Sec’ could also have referred to the Tall´an language,

later ethnographic research by Br¨uning (1922) gives support to the idea of a special

connection between Olmos and Sechura suggested by oral tradition and the coincidence

of weaving terminology. For a detailed discussion see Torero (1986), who ventures the

idea that a Callahuaya-type situation may have existed in Olmos (cf. section 3.5). Finally,

the linguistic unity of Olmos and Sechura–Tall´an is confirmed in an archival document

of 1638 enumerating the administrative and religious divisions of the northern Peruvian

coastal region (Ramos Cabredo 1950: 53–5).

The original language situation in the interior highland part of the department of

Piura with its centres Ayavaca and Huancabamba is difficult to reconstruct. Today its

predominantly indigenous population is reported to be Spanish-speaking. During the

colonial period Quechua may have been the dominant language in that area, as was

191

It may be assumed that the difference between -u

˜

m and -

˜

umreflects an inconsistency in Mart´ınez

Compa˜n´on’s orthography.

3.9 Extinct and poorly documented languages 401

also the case further east in Tabaconas, in the area descending towards the Amazon

(Torero 1993a), and in the Huambos area further south in the department of Cajamarca.

A systematic investigation of place names and family names in eastern Piura remains a

task for the future.

Another well-attested language in northern Peru is Culli (or Culle). Culli was once the

dominant language in the Andean hinterland of the coastal town of Trujillo. Its former

area comprises four provinces of the department of La Libertad (Julc´an, Otuzco,

Santiago de Chuco and S´anchez Carri´on), the province of Cajabamba (department of

Cajamarca) and the province of Pallasca (department of Ancash). Pallasca was part

of the colonial province of Conchucos,which also included Quechua-speaking areas

in northern and eastern Ancash. The Culli translation of Conchucos is ‘water land’

(co˜n ‘water’, chuco ‘land’). The Mara˜n´on river valley constituted the eastern border

of the Culli-speaking area. To the southwest it bordered on the Quingnam language of

the Trujillo coastal plain (see section 3.4). Further extensions of the Culli language in

Ancash and Cajamarca, as well as the possibilities of overlap with other languages, are

controversial.

The main historical centre of the Culli-speaking people was the town of Huamachuco,

now the capital of S´anchez Carri´on province. It was the seat of an important religious cult

to the creator god Ataguju and the thunder god Catequil. In spite of violent persecution

by the Incas, the Huamachuco cult was still vigorous when the Spaniards arrived. The

Augustinian friars Juan de San Pedro and Juan del Canto, who soon after the conquest

attempted to convert the local population, wrote a detailed account of local beliefs and

customs, in which a Huamachuco language and several native names and terms are

mentioned (Castro de Trelles 1992). Towards the end of the sixteenth century a travel

account by Toribio de Mogrovejo, archbishop of Lima, of his visit to the area refers to

a language called Linga or Ilinga (cf. Rivet 1949). Notwithstanding the fact that these

terms seem to represent modified versions of lengua del Inga ‘language of the Inca’,

the geographic setting indicates that only Culli could be meant. The earliest mention of

the name Culli itself is found in the abovementioned document of 1638 published in

Ramos Cabredo (1950). For a historical overview of the Culli language and its speakers

see Silva Santisteban (1982).

The primary sources for Culli are two word lists. One list of 43 words, referring to the

Culli language of the province of Huamachuco, is found in Mart´ınez Compa˜n´on (1985

[1782–90]), whereas the other was collected around 1915 in a hamlet called Aija near

Cabana in the province of Pallasca by a local parish priest, father Gonz´alez. This list of

19 words was published in Rivet (1949: 4–5).

192

In recent years, a number of students

from the area (Flores Reyna 1996; Andrade Ciudad 1999; Cuba Manrique 2000; Pantoja

192

We have obtained the information concerning the place of origin of the Gonz´alez list from the

field notes of Walter Lehmann, kept at the Ibero-American Institute in Berlin.

402 3 The Inca Sphere

Alc´antara 2000) have succeeded in expanding the lexical data base of the Culli language

by collecting words and expressions still in use today. Flores Reyna reports that Culli was

spoken by at least one family in the town of Tauca (Pallasca province) until the middle

of the twentieth century. Although Culli has been replaced by Spanish, the possibility

that speakers survive in remote villages cannot be ruled out entirely (cf. Adelaar 1988).

The ethnolinguistic atlas published by Chirinos Rivera (2001) contains several mentions

of municipalities in the Culli area for which the census of 1993 reports the existence of

speakers of an unidentified native language.

In spite of the extremely scanty data it is possible to tentatively determine a number of

characteristics of the Culli language. In compounds a modifying element precedes the

head, like in Quechua. Verb forms as given by Mart´ınez Compa˜n´on all end in a suffix -`u

([u]∼ [w]), e.g. canqui`u ‘to laugh’, ˇcollap`u ‘to die’ (see below for a possible interpreta-

tion of the diacritic on ˇc ). The language may have had prefixes for possessive personal

reference considering the fact that several kinship terms feature an initial velar stop

(viz. quin`u ‘father’, quimit ‘brother’, ca˜ni ‘sister’). Possibly, the same element is found

in quiyaya,aform of ritual singing, which may contain the word yaya ‘god’.

193

Like

Quechua and Aymara, the language may have had a three-vowel system (a, i, u). The oc-

currence of mid vowels (e, o)islimited and seems to be favoured by the neighbourhood

of c, qu, g,nomatter if the latter occur in clusters or by themselves (e.g. mosˇc´ar ‘bone’,

ogˇoll ‘child’, co˜n ‘water’; Quesquenda ‘a place name’). It suggests that the language

may have had a velar–postvelar opposition, an assumption fed by the fact that Mart´ınez

Compa˜n´on often uses a haˇcek-style diacritic when c and g are adjacent to a mid vowel or

a. Other instances of mid vowels (especially o) are found in the environment of r (e.g. in

the place name Choroball) and in contexts in which vowel harmony appears to play a role

(e.g. in Chochoconday, the name of a mountain). Variation between mid and high vowels

is frequent in place names (e.g. Sanagor´an, Candigur´an; Corgorguida, Llaugueda). A

characteristic feature of Culli is that the second member in a compound often begins

with a voiced stop, producing internally dissimilar consonant clusters when the first

member ends in a voiceless consonant (for instance, in place names such as Chiracbal

and Ichocda). If the same element occurs independently or in initial position it has a

voiceless stop. Compare, for instance, Chusg´on (a river name) and Conchucos (both con-

taining the element con∼-gon ‘water’); also Parasive and Pushvara.Frequent endings of

Culli place names are -day∼-tay ‘mountain’, -chugo∼-chuco ‘earth’, -gon∼-go˜n ‘water’,

-gueda ∼-guida∼-queda ‘lake’, -gur´an∼-gor´an ‘river’, -pus ∼-pos ‘earth’; the elements

193

The analysis of qu(i)- as a prefix is, however, contradicted by the fact that some early Culli

family names contain the element quino (Pantoja Alc´antara 2000). In addition, Torero (1989:

225) recognises the element quin`u in the divinity name paiguinoc ‘lord of the guinea-pigs’

mentioned in the Augustinian chronicle. Note also that quiyaya appears as quillalla in Mart´ınez

Compa˜n´on.

3.9 Extinct and poorly documented languages 403

-bal∼-ball, -bara∼-huara∼-vara, -chal, -da∼-ta, -gal∼-galli∼-calli, -ganda, -maca,

-sicap∼-s´acap(e) ∼-ch´acap(e), all of undetermined meaning; and the borrowed ele-

ments -malca ‘village’ and -pamba ‘plain’ (from Quechua -marka and -pampa, respec-

tively). For an extensive list of Culli place names see Torero (1989). Place names com-

bining a Culli element with a Quechua or a Spanish element (Mumalca,

194

Naopamba,

Cruzmaca) are frequent and indicate that these languages must have coexisted for a

considerable time.

From a phonological point of view, it is possible to distinguish several dialect areas.

Place names in the province of Pallasca and neighbouring parts of Santiago de Chuco ex-

hibit endings with the palatal final consonants -˜n [n

y

] and -ll [l

y

] (e.g. Acogo˜n, Camball)

whereas non-palatal endings appear elsewhere (e.g. Chusg´on, Marcabal). The distribu-

tion of palatal and non-palatal endings coincides with the geographical distribution of

the lexical endings -day and -ganda as noted by Torero (1989: 226).

The Culli word lists show a relatively high incidence of Quechua loans (e.g. aycha, Qu.

ayˇca ‘meat’; challuˇa, Qu. ˇcal

y

wa ‘fish’; cuhi, Qu. kuˇsi ‘pleasure’). The item mi`u ‘to eat’

appears to reflect a hypothetical pre-Quechua *mi-,which can be reconstructed on the

basis of modern Quechua miku- ‘to eat’ and miˇci- ‘to herd’. Other items, however, show

no relationship with Quechua whatsoever and suggest that the language is genetically

independent. Similarities with the Piuran languages and Mochica are also limited (cum`u,

Col´an c˜um ‘to drink’; chuip, Catacaos chupuchup ‘star’; paihaˇc, Mochica pey ‘herb’).

They may be due to contact.

The department of Cajamarca has a dense, predominantly indigenous population. The

accounts of colonial inspection visits (visitas)tothis area (Remy and Rostworowski de

Diez Canseco 1992) feature a wide variety of family names reflecting the existence of

several unidentified languages. The toponymy is also highly varied and exotic. Never-

theless, only Quechua has survived in a small number of well-defined localities. Interest-

ingly, Cajamarca Quechua (Quesada Castillo 1976a, b) contains a substantial amount of

non-Quechuan vocabulary. In Pantoja Alc´antara’s study of the Culli linguistic heritage

in the Spanish of Santiago de Chuco, an area quite distant from Cajamarca, the follow-

ing correspondences between Santiago de Chuco Spanish and Cajamarca Quechua have

come to light:

Santiago de Chuco Spanish Cajamarca Quechua

ˇcukake ˇsukaki ‘headache with nausea’

ˇcurgap(e) ˇcurʁap ‘cricket’

dasdas dasdas ‘hurry up!’

inam inap ‘rainbow’

194

The meaning of mu is ‘fire’; the other Culli elements have not been identified.