Adelaar Willem, Muysken Pieter. The languages of the Andes

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

324 3 The Inca Sphere

Table 3.16 Mochica vowels as represented in Carrera Daza (1644)

and Middendorf (1892)

Carrera Daza a, ˆae i o,ˆou,ˆuoe

Middendorf a, ¯a, ˘ae(¯e) ¯ı, (i), ˘ı¯o, (o), ˘ou,¯u, ˘u¨a, ˚u

English ‘but’. No length distinction is reported for the front mid vowel e.

116

It is doubtful

whether all these options were indeed distinctive. However, the length distinction seems

to have been functional, considering the minimal pairs recorded by Middendorf (cf.

Cerr´on-Palomino 1995b: 81–2):

117

(236) pok p¯ok

‘to enter’ ‘to be called’

(237) rak r¯ak

‘mountain-lion’ ‘excrement’

(Middendorf 1892: 54)

The vowel symbols used by Carrera Daza and Middendorf are summarised in

table 3.16. The vowel symbols used by Middendorf which are not presented as part

of his inventory are given in parentheses.

The intricacies of the Mochica consonant inventory motivated Carrera Daza to in-

troduce several new symbols and combinations of existing symbols, such as <cɥ>,

<tzh> and <xll>. Their interpretation continues to be a matter of debate, in particular

because the sounds they represent were subject to change during the last centuries of

the language’s existence. Hovdhaugen (1992) and Torero (1986, 1997) have established

a correlation between palatal and plain consonants, which covers most of the system,

except for the labial series and the vibrants. The occurrence of a palatality contrast in the

velar series is defended in Torero (1986, 1997). The areas of the consonant system that

were most affected by change during the period between the seventeenth and nineteenth

centuries were the laterals and the sibilants. The laterals partly developed into velar

fricatives; a crucial sibilant contrast disappeared.

Carrera Daza appears to have represented the Mochica consonants quite adequately,

but, as in contemporary Spanish, competing symbols and symbol combinations some-

times referred to a single sound. The absence of comments on the pronunciation of

a symbol may be held to indicate phonetic similarity with the corresponding Spanish

sound. This is of particular importance for the sibilants.

116

Although no long ¯e is foreseen in Middendorf’s phonetic introduction, he does, inconsistently,

use that symbol in his examples (for instance in k¯en ‘half’, Middendorf 1892: 62).

117

At least in one case, a long vowel in Middendorf is matched by a more complex sequence

in seventeenth-century Mochica: Carrera Daza piiœc [piyək] ‘to give’ versus Middendorf p¯ık

(cf. Torero 1997: 120).

3.4 The Mochica language 325

The symbols for voiceless labial consonants <p> and <f> were probably pronounced

as in Spanish, although the fricative f may have been bilabial, rather than labiodental. In

the nineteenth century, f had developed an optional voiced allophone in intervocalic and

syllable-final positions; e.g. c

ɥ

œfœt ‘snake’ (Villareal 1921: 17) is represented as ´chuvet

or ts˚uv¨at in Middendorf. A remarkable fact is the absence of the glide or semi-vowel [w]

in seventeenth century Mochica. In loans from Quechua or Spanish, [w] or [β]ofthe

original language were consistently replaced by <f>, e.g. facc

ɥ

a ‘poor’ (Villareal 1921:

21) from Quechua wakˇca, and fak ‘ox’ (Middendorf 1892: 60) from Spanish vaca.As

in most countries where a Spanish writing tradition prevails, Carrera Daza wrote <qu>

for the velar stop before e and i,but<c> elsewhere. Seventeenth-century Mochica

apparently had no velar fricatives.

The nasal series comprised four positions: bilabial <m>, alveodental <n>, palatal

<˜n> and velar <ng>. Carrera Daza also uses the velar nasal symbol when the velar

character of the sound can be derived from environmental restrictions, as in ¸cengque

‘throat’ (Altieri 1939: 80). The vibrant series presumably included a trilled <rr> and a

tap <r>,acontrast that does not seem to have been distinctive.

118

Both <rr> and <r>

are found in word-initial, medial and final position. The glide y (often written <i>, see

above) was a consonant phoneme in Mochica.

In the alveodental series two sounds were recorded, voiceless <t> and voiced <d>.

The status of <d> is somewhat problematic, as it did not occur in word-initial position

but mainly in suffixes and at the end of morphemes. If it was a voiced stop, it would

have had neither velar nor labial counterparts. The lack of comments in the sources

concerning its pronunciation suggests that it was in most instances pronounced as in

Spanish, in which case it may have been a fricative.

The sibilants and their corresponding affricates were characterised by a contrast be-

tween a palatal articulation, on the one hand, and what were possibly apical and dental

articulations on the other. The palatal sibilant and affricate were written <x> [ˇs] and

<ch> [ˇc], respectively, as was the common usage in many parts of the Spanish realm.

The non-palatal sibilants were indicated by means of the symbol sets <s>, <ss>, and

<c>, <¸c>, <z>, respectively. Torero (1997: 109–12) assigns an apico-alveolar inter-

pretation (presumably as in Castilian Spanish) to the <s>, <ss> set, which mainly rests

on the fact that Carrera Daza’s comments do not suggest otherwise. Cerr´on-Palomino

(1995b: 103–5) prefers a retroflex interpretation. Both authors coincide in assigning

an (alveo)dental value to the <c>, <¸c>, <z> set. The real phonetic nature of these

two sets of symbols may very well always remain unknown, because the assumed con-

trast was lost after Carrera Daza’s time. Torero further analyses the sequences <ci>,

118

Remember, however, the case of the Quechua dialect of Pacaraos (section 3.2.9.), which exhibits

a non-predictable contrast between r and rr,even though minimal pairs are lacking.

326 3 The Inca Sphere

Table 3.17 Sibilants in seventeenth-century

Mochica (following Torero 1997)

Plain Palatal

Dental c, ¸c, z [s] ci, ¸ci, iz [s

y

]

Apical s, ss [¸s] x, ix [ˇs]

<¸ci>, <iz> as representing the palatal counterpart of the dental sound represented by

the <c>, <¸c>, <z> set. This is plausible because in Carrera Daza the palatality marker

<i> is frequently found in that environment, but never in the immediate vicinity of

<s>, <ss>.Taking a further step, Torero then interprets the palatal sibilant <x> as

the palatal counterpart of <s>, <ss>. His analysis of the sibilants is represented in

table 3.17.

The coincidence of the presumed apical and dental series led to a reordering of the

palatality distinction. This becomes evident in Middendorf’s work, where the symbols

s and ss can be accompanied by i when s, ss corresponds to <c, ¸c, z> in Carrera

Daza.

(238) ¸ciad-ei˜n (Villareal 1921: 12) siad-ei˜n, ssiad-ei˜n (Middendorf 1892: 89, 91)

sleep-1S.SG

‘I sleep’

The affricate <tzh>, one of the new symbol combinations introduced by Carrera

Daza, corresponds with an alveodental affricate [t

s

]innineteenth- and twentieth century

Mochica. There would be no reason to assume that the seventeenth-century affricate

recorded by Carrera Daza was anything else than [t

s

], had he not himself underscored

the exotic properties of the sound represented by his symbol <tzh>. Carrera Daza’s

orthography also suggests something more complex than [t

s

]. Where other authors stick

to the alveodental interpretation, Torero (1997) holds that <tzh> must be interpreted as

an apico-alveolar affricate, which would indeed have been an exotic sound to the ears

of a colonial Spaniard.

119

The subsequent disappearance of the apical–dental contrast

would then have affected the affricate <tzh> as well, reducing it to a more ‘normal’

alveodental affricate [t

s

].

The sequence <tzh> is also found in combination with the palatality marker <i>,

for instance in cuntzhiu ‘overhanging lock of hair’ (Villareal 1921: 14). Hovdhaugen,

119

An apico-alveolar affricate [t

¸s

], traditionally written as ts,isfound in Basque. One cannot

expect Carrera Daza to have been familiar with it.

3.4 The Mochica language 327

who takes <tzh> to be dental rather than apico-alveolar, treats the <tzhi> combination

as its palatal counterpart [c

y

],

120

but Torero (1997: 115) suggests that it may rather

be the palatal counterpart of the stop t. Whatever solution is chosen, the sound was

presumably an affricate since Middendorf (1892: 59) recorded kunzio for the word in

question.

One of the most intriguing symbols in Carrera Daza’s work is <cɥ>,which is reported

to represent a sound similar to, but distinct from the affricate symbolised by <ch> [ˇc],

hence the ‘reversed’ h.Inthe seventeenth century it was found in all positions, including

the word- and syllable-final positions, e.g. in lec

ɥ

‘head’. Although several instances

of original <cɥ> had become ch by the end of the nineteenth century, the sound in

question was still clearly present in the time of Middendorf, who represents it as ´ch.He

describes the sound as an alveodental stop followed by an ‘ich-laut’ [t

¸c

] (Middendorf

1892: 51). Carrera Daza’s <cɥ> is interpreted as a palatalised alveodental stop [t

y

]

by Cerr´on-Palomino (1995b: 96), as a palatalised palatal affricate [ˇc

y

]byHovdhaugen

(1992) and as a palatalised velar stop [k

y

]byTorero (1986, 1997). The latter somewhat

remarkable interpretation is based on the argument of homorganity in consonant clusters.

As a matter of fact, <cɥ> wasfavoured over <ch> after a velar stop during the process

of borrowing the Quechua word wakˇca ‘poor’. The latter became faccɥa [fakt

y

a ∼

fakk

y

a], not *faccha [fakˇca], in Mochica. Furthermore, nasal consonants could be velar

before <cɥ>, suggesting assimilation to the initial sound of an affricate with a velar

initial element, as in (239):

(239) cangcɥɥu (Villareal 1921: 12) kangchu (Middendorf 1892: 59) ‘jaw’

However, there are counterexamples, such as (240), where no assimilation to the velar

position has been recorded.

(240) cœncɥɥo (Villareal 1921: 12) k˚uncho (Middendorf 1892: 61) ‘meat’

Seventeenth-century Mochica had a remarkable system of laterals, in which the op-

positions of voice and palatality played a central role. One of the special symbols in-

troduced by Carrera Daza, <xll> has been identified as a voiceless palatalised lateral

[l

y

](Torero 1986).

121

It contrasted with a voiced counterpart <ll> l

y

. Between the sev-

enteenth and the nineteenth centuries the voiceless sound developed into a palatalised

velar fricative [¸c], written

’

by Middendorf (241), whereas the voiced sound remained

unchanged (242).

120

For reasons of notational uniformity, we substitute [c

y

] for Hovdhaugen’s [t¸¸s].

121

Hovdhaugen interprets this symbol as a palatalised alveopalatal fricative [ˇs

y

].

328 3 The Inca Sphere

(241) xllaxll (Villareal 1921: 44)

’

ai

’

(Middendorf ‘silver’

1892: 62)

(242) llapti loc (Villareal 1921: 26) llapti jok (Middendorf ‘sole of

1892: 59) the foot’

Carrera Daza’s grammar does not contain evidence of the existence of a pair of non-

palatal laterals parallel to the palatal ones. Only one lateral <l> is attested. In many

cases this lateral developed into a velar fricative j [x] between the seventeenth and the

nineteenth centuries; cf. (242), and the examples in (243):

(243) a. la (Villareal 1921: 24) j¯a (Middendorf ‘water’

1892: 63)

b. col (Villareal 1921: 14) koj (Middendorf ‘horse’

1892: 60) (< * ‘llama’)

In other cases, however, the lateral was preserved (244). On this basis and for reasons of

symmetry, one may assume, with Torero (1986), that there may have existed a contrast

between voiced and voiceless plain laterals as well, one of which developed into a

velar fricative, whereas the other did not. Since there is no direct evidence for such a

development, it must remain a matter of speculation.

(244) loqu-ei˜n (Villareal 1921: 26) lok-ei ˜n (Middendorf 1892: 184)

want 1S.SG

‘I want’

Table 3.18 presents an overview of the principal consonant symbols and symbol

combinations used by Carrera Daza and Middendorf and their possible values at different

stages of their development.

3.4.2 Mochica grammar

Mochica is predominantly a suffixing language with a rather loose morphological struc-

ture. Grammatical relations are indicated by case or postpositions. There are no affixes

indicating the grammatical person of the possessor. The genitive case form of per-

sonal and demonstrative pronouns is used for that purpose. As in Aymara and Quechua,

modifiers precede the head. Irregular forms, including those involving ablaut and root

substitution, are common. As a result of the way in which the language was documented,

it is no longer possible to obtain a full picture of these irregularities. Furthermore, the

sources show a certain amount of insecurity where vowels are concerned. Very often,

alternative possibilities are presented as equivalent, without a suggestion of semantic or

pragmatic differences that could have played a role.

3.4 The Mochica language 329

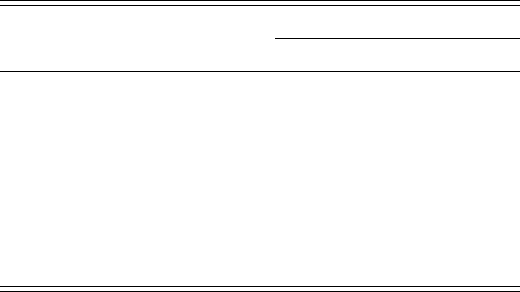

Table 3.18 Overview of the consonant symbols in the

Mochica grammars of Carrera Daza (1644) and

Middendorf (1892)

Carrera Daza Middendorf Possible phonetic values

(1644) (1892) and historical development

ppp

ff,vf,ϕ>v, β

ttt

ddð, θ

c, ¸c, z s, ss s

tzh ts t

¸s

,t

s

> t

s

s, ss s, ss ¸s > s

ch ch ˇc

xˇsˇs

cɥ ´ch k

y

,t

y

,t

¸c

> t

y

,t

¸c

c, qu k k

xll

’

l

y

> ¸c

ll ll l

y

lll

ljl,l

> x

r, rr r, rr r, rr

mmm

nnn

˜n˜nn

y

ng ng ŋ

i,y i y

Several characteristics of Mochica are reminiscent of the Mayan languages. The

language has a system of numeral classifiers and a fully developed passive. Passive

constructions are often preferred over active constructions, the agent being expressed

in the genitive case or, with some nouns (mainly kinship terms), by a special agentive

case marker. Many substantives have two forms, a possessed (relational) form and a

non-possessed (absolute) form.

One of the most remarkable features of Mochica is the use of verbal personal reference

markers that can either be suffixed to the verb stem itself, or follow the element preceding

the verb stem. They indicate the person of the subject, whereas person of object is not

expressed in the verb form. Although these personal reference markers are not formally

related to the independent personal pronouns, their combined use as subject markers is

considered ungrammatical (Villareal 1921: 6). In example sentence (245), the marker

for first-person singular -ei˜n is attached to the root met ‘to bring’. Alternatively, it can

330 3 The Inca Sphere

be located after the element which precedes the root, in this case the object pup ‘wood’

(246):

(245) met-ei˜n pup m¨ai ˜nanai-n¨am

bring-1S.SG wood I.G house make-F.SP

‘I bring wood in order to build my house.’

(Middendorf 1892: 160)

(246) pup ei˜n met m¨ai ˜nanai-n¨am

wood 1S.SG bring I.G house make-F.SP

‘I bring wood in order to build my house.’

(Middendorf 1892: 160)

Alternatively, the personal pronoun moi˜n ‘I’ is located before the root met from which

it is separated by either one of the elements e, fe or ang. The grammatical descriptions

do not provide information as to a possible semantic difference between these three

options, which are all translatable as ‘I bring’ (247):

(247) moi˜n´e met xllac

122

or moi˜nfemet xllac or moi˜n ang met xllac

Ibebring fish

‘I bring fish.’

(Altieri 1939: 51)

The invariable elements e, fe and ang are described as equivalents of the verb ‘to be’

and can be used as such in combination with a free pronoun (248):

(248) moi˜neor moi˜nfeor moi ˜n ang

Ibe

‘I am.’

(Villareal 1921: 5)

Mochica also has a conjugated verb chi conveying the meaning ‘to be’.

123

In combi-

nation with this verb, the use of the independent pronoun as subject is rejected. When

followed by the element -pa, the conjugated forms of the verb ‘to be’ obtain the meaning

of ‘to have’ (249):

(249) chi-˜n

124

chi-˜n-pa

be-1S.SG be-1S.SG-have

‘I am.’ ‘I have.’

(Villareal 1921: 5, 100)

Finally, the notion ‘to be’ can be expressed by locating a personal reference marker

directly after a full pronoun. In that case the use of the independent pronoun in

122

The element e is often, but not always, found as ´e in Carrera Daza (Altieri 1939).

123

The verb chi is mainly used in a copula function. For existential ‘to be’ loc/lok is preferred.

124

For the suppression of the vowel in -ei˜n see below.

3.4 The Mochica language 331

Table 3.19 Personal reference in Mochica (Altieri 1939: 19–21)

Pronouns

Affixes Nominative Genitive

1 pers. sing. -ei˜n moi˜n mœi˜n[-ˆo]

1 pers. plur. -eix mœich mœich[-ˆo]

2 pers. sing. -az tzhang ∼ tzha tzhœng[-ˆo]

2 pers. plur. -az-chi tzhœich ∼ tzha-chi tzhœich[-ˆo]

3 pers. sing. (close) -ang mo mu-ng[-ˆo]

(neutral) ¸cio ¸ciu-ng[-ˆo]

(far) aio aiu-ng[-ˆo]

3 pers. plur. (close) -œn-ang mo-ng-œn mu-ng-œn[-ˆo]

(neutral) ¸cio-ng-œn ¸ciu-ng-œn[-ˆo]

(far) aio-ng-œn aiu-ng-oen[-ˆo]

combination with the corresponding personal reference marker does not appear to be

problematic (250):

(250) moi˜nei˜n

I 1S.SG

‘I am.’

(Villareal 1921: 5)

Interrogative sentences of the disjunctive type provide the only context in which the

personal reference markers occur in a sentence-initial position, e.g. in (251) and (252),

without having to be preceded by any other element. It follows from this that the Mochica

personal reference markers cannot be considered to be bound affixes in the strict sense,

although they do behave as such when they occur after a verb stem (see below).

(251) as ton-od ts¨ang ef

2S beat/kill-PA you.G father.RL

‘Did you beat your father?’

(Middendorf 1892: 136)

(252) ang funo-´ch¨am

3S eat-PR

‘Is he/are they eating?’

(Middendorf 1892: 95)

The personal reference system of Mochica is based on three persons and two numbers.

Personal pronouns exist for first and second persons singular and plural. For third-person

demonstrative pronouns are used. In third-person forms and in nouns in general, plurality

is expressed optionally by means of the suffix -œn/-¨an.Intable 3.19 the personal reference

markers are represented in their affix shape, along with the corresponding free pronouns

332 3 The Inca Sphere

(including demonstratives for third person) in their nominative and genitive forms. The

short forms of the genitive pronouns are used as modifiers in noun phrases and as agents

in passive constructions. The long forms in -ˆo /-¯o are used in predicative constructions

with ‘to be’.

125

As shown in table 3.19, the vowel of the first-person suffixes -ei˜n,-eix/-eiˇs can be

suppressed by a preceding vowel, as in chi-˜n ‘I am’, funo-i˜n ‘I eat’ (funo ‘to eat’). The

vowelofthe second-person suffix -az/-as is unstable; it is alternatively found as -œz/-¨as

or -ez/-es, and it is also affected by suppression after another vowel, e.g. chi-z ‘you are’,

funo-z ‘you eat’. Note that the velar nasal preceding the pluralising suffix -œn in the

nominative forms (in mo-ng-œn, for instance) is not part of the postvocalic realisation

of that suffix. With other vowel-final roots, such as ¸ciorna/ssiorna ‘(someone) alone’,

a hiatus is preferred before -œn: ¸ciorna œn/ssiorna-¨an.Inthe genitive forms, however,

-ng-isthe normal postvocalic realisation of the marker for that case (here accompanied

by ablaut).

Although Mochica has no general case marker for objects – they are indicated in the

same way as subjects –, some pronouns do have a special form for that purpose. A first-

person-plural accusative or dative object (‘us’) is indicated by ˜nof; the demonstratives

have object forms moss, ¸cioss/ssioss and aioss, respectively.

Case marking in Mochica is constructed around the nominative–genitive distinction.

The remaining case markers have been analysed as postpositions, which are either added

to the nominative or to the genitive form.

126

It should be observed, however, that this

is the traditional view, and that some of the elements which are directly added to the

‘nominative’ root, such as -len ‘with (comitative)’, -mœn/m¨an ‘as’, ‘following’, -na

‘through’ (adverbialiser), -(ng)er ‘with (instrumental)’, -(n)ich ‘from’, -pœn/-p¨an ‘as’,

‘in the function of’, -tim ‘for the sake of’ and -totna ‘towards’ may be case suffixes,

rather than postpositions

127

(cf. Middendorf 1892: 125–6).

(253) ssiung fanu-len

128

he.G dog-C

‘with his dog’

(Middendorf 1892: 98)

(254) pe˜n-o-p¨an ang ak-¨am

good-AR-CP be say-PS

‘He is held to be good.’

(Middendorf 1892: 100)

125

The existence of forms with and without -ˆo motivated Carrera Daza to declare that there were

two genitives in Mochica (Altieri 1939: 15–16).

126

There is one preposition pir ‘without’. It is followed by substantives in their relational form

(e.g. pir chi¸cœr ‘without judgment’, from chi¸cœc ‘judgment’, ‘understanding’).

127

The allomorphs with an initial nasal are postvocalic; -totna may be related to tot ‘face’.

128

Middendorf (1892: 55) mentions a case of -len following the short form of the genitive (in

fanu-ng-len ‘with the dog’).

3.4 The Mochica language 333

One postposition, the benefactive marker -pœn/-p¨an, follows the ‘long’ genitive case

form, expanded with the element -ˆo.

(255) mo cɥɥilpi ang mœi˜n ef-ei-ˆo-pœn

this blanket be I.G father-G-AJ-B

‘This blanket is for my father.’

(Altieri 1939: 13)

The postpositions that follow the ‘short’ genitive form all have to do with location in

space. The marker -nic/-nik indicates location or motion towards ‘in’, ‘at’, whereas -lec/

-lek refers to a less specific location ‘near’, ‘at’ (256). Several substantives have special

locative forms in which an ending -Vc/-Vk, with an unpredictable vowel i, e or œ/¨a,is

added directly to the root, e.g. en-ec/en-ek ‘at home’ (cf. an ‘house’), mœc

ɥ

-œc/m¨ach-¨ak

‘in the hands’ (cf. mœc

ɥ

/m¨ach ‘hand’). These cases are said by Middendorf (1892: 96)

to take their origin in the combination of genitive stems followed by -nic/-nik,aconclu-

sion which in our view remains open for discussion. The remaining postpositions that

follow genitive stems indicate spatial positions in relation to an object. Several of them

are derived from body part names and contain the element -Vc/-Vk (257), e.g. lec

ɥ

œc/

jech¨ak ‘above’ (cf. lec

ɥ

/jech ‘head’), luc

ɥ

œc/juch¨ak ‘among’, ‘between’ (cf. loc

ɥ

/joch

‘eyes’), tutœc/tut¨ak ‘before’, ‘in front of’ (cf. tot ‘face’). The postpositions capœc/kap¨ak

‘on top of’, ssecœn/ssek¨an ‘below’ and turquich/turkich ‘behind’ are less easy to

analyse.

(256) pedro-ng-lec

Pedro-G-L

‘at Pedro’s’

(Villareal 1921: 110)

(257) chap-e jech-¨ak

129

roof-G head-L (above)

‘on top of the roof’

(Middendorf 1892: 97)

The shape of the genitive of Mochica nouns is partly unpredictable. In wordlists (e.g.

Middendorf 1892: 58–64; Villareal 1921: 9–44) the genitive ending is added to each

entry. According to Middendorf (1892: 52–4), -œr-ˆo/-¨ar-¯o is found after voiceless stops,

nasals and part of the affricates (ts, ch). After other consonants -ei-ˆo/-ei-¯o is found. The

genitive ending after vowels is -ng-ˆo/-ng-¯o. The plural suffix -œn-/-¨an- is inserted before

the genitive suffixes -œr-/-¨ar- and -ei-,but after -ng-.

(258) m¯ud-ei-¯om¯ud-¨an-ei-¯o

ant-G-AJ ant-PL-G-AJ

‘belonging to the ant’ ‘belonging to the ants’

(Middendorf 1892: 53)

129

Villareal (1921: 110) an-i c

ɥ

ap-œ lec

ɥ

-œc ‘above the roof of the house’.