Adelaar Willem, Muysken Pieter. The languages of the Andes

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

254 3 The Inca Sphere

subject is involved. It may be either a mistake, or a sign that the distinction is no longer

actively used by the narrator.

14. “ima-tax

.

ˇcay-ri asna-n madeha henti-man?”

what-SQ that-TO.IR smell-3S string people-AL

‘“What is it that smells of a string of people here?”’

The suffix -tax

.

follows WH-phrases when used interrogatively. The independent suffix

-ri indicates the topic in an interrogation. A Spanish expression madeja de gente ‘string

of people’ appears as madeha hente; its deeper sense remains unexplained. Gelles and

Mart´ınez (1996: 66) translate it as ‘human hair’.

3.2.11 Literary production in Quechua

In pre-Spanish times Quechua was not a written language. Chroniclers of Inca history

and other early colonial accounts emphasise the absence of an indigenous writing system.

Knotted threads, called quipus (Quechua k

h

ipu), were used as a mnemotechnic device for

economic and administrative purposes. To this effect, the Incas maintained specialised

officials, the quipucamayoc (Quechua k

h

ipukamayuq). Entrusted with the keeping of

the quipus, the quipucamayoc relied on their memory in order to supply the additional

information the quipus could not convey. Contemporary witnesses praise the high per-

fection of quipu writing, which remained in use for local administration well into the

colonial period. However, hard evidence that the quipus could represent real language of

any form is lacking, in spite of claims to the contrary by some colonial authors.

42

A set

of heraldic symbols, which were depicted on Inca tunics known as unku,have also been

interpreted as samples of an indigenous writing system. But again, there is no reliable

evidence that these symbols were related to language in any direct way.

Whatever literary production the Incas had was transmitted orally. Samples of such

literature are found in the work of Crist´obal de Molina (1574) and Guaman Poma de Ayala

(1615). Inca literary production has been the object of ill-fated attempts to categorise

it in terms of European literary genres, as a means to enhance the prestige of Andean

culture within an indigenista perspective. Most likely, the literary production of Inca

society mainly comprised myths and folk songs, as is still the case today in traditional

Andean society. Theatre performances, accompanied by chorals, have survived in a

traditional context. Best known is the cycle describing the death of Atahuallpa, the Inca

ruler executed by the Spaniards (Lara 1957; Meneses Morales 1987; Husson 2001).

Such performances, although heavily transformed, may have pre-Spanish roots.

42

The discussion about an alleged literary use of the quipus was revived after the discovery in

Italy of a manuscript attributed to Blas Valera, a dissident Jesuit and defender of the Indians

(Animato, Rossi and Miccinelli 1989). The authenticity of this manuscript remains disputed.

3.2 The Quechuan language family 255

Foralanguage of such importance as Quechua, surprisingly little text material has

survived from the colonial epoch. Without any doubt, the longest and most interesting

text belonging to that period is the Huarochir´ı manuscript (Taylor and Acosta 1987;

Salomon and Urioste 1991). This document was written before 1608 by local literate

Indians on behalf of the idolatry fighter (extirpador de idolatr´ıas)Francisco de Avila,

who used it as an instrument for the eradication of native cults. De Avila was parish priest

in San Dami´an de Checas in the province of Huarochir´ı, in the mountainous interior of

what is today the department of Lima. The Huarochir´ı manuscript contains an overview

of local mythology and interethnic relations, descriptions of rituals and celebrations, as

well as penetrating accounts of the interaction between Christian and native beliefs.

Theatre plays in Quechua became popular in Cuzco towards the end of the seventeenth

century. The themes treated were mostly religious (autos sacramentales, among other

work) and of European inspiration. Although the language was Quechua, the theatri-

cal form (metre, division into acts) was obviously Spanish. Best known among these

theatre plays is the Ollanta(y); for a recent edition see Calvo P´erez (1998a). It treats a

romanticised theme of Inca history, the love between Ollantay, an Inca general of humble

descent, and the Inca princess Cusi Coyllur. Indigenista intellectuals and admirers of the

Inca past have long claimed a pre-Columbian origin for the Ollantay. Obviously, such a

claim can only be upheld for the story underlying the play, not for the play itself. For a

detailed account of the colonial Quechua theatre tradition see Mannheim (1991).

After the Quechua language was banned from public use as a reaction to the Tupac

Amaru rebellion of the 1780s, Quechua literary production all but came to a standstill.

Forarenewed interest in Quechua literature, we must await local indigenista movements

that came into existence in the early twentieth century. These movements were mostly

headed by mestizos, not by traditional Indians. Among those authors who wrote poetry

in Quechua as an expression of individual experience, we may mention the Cuzco

landowner Alencastre, also known under the pseudonym Kilku Warak’a, and Jorge Lira,

a Cuzco parish priest. In Ecuador, the landowners Luis Cordero and Juan Le´on Mera

wrote Quechua poetry around the turn of the century. The Bolivian scholar Jes´us Lara

published several anthologies of Quechua literature of all genres (see, in particular, Lara

1969). For a choice of theatre plays in Quechua dating from the early twentieth century,

authored by Nemesio Z´u˜niga Cazorla, see Itier (1995).

The bulk of twentieth-century Quechua literature, however, is traditional. It consists of

myths, traditional narratives, autobiographical accounts, songs and riddles. Some of these

texts represent blends of Andean traditions and elements imported from Europe. The last

three decades of the twentieth century have witnessed a huge production of anthologies

and compilations of traditional text in different Quechua dialects. To mention just a few

of them, the autobiography of Gregorio Condori Mamani (1977), an illiterate peasant

from Acopia (Cuzco), was taken down in writing by two anthropologists, Escalante and

256 3 The Inca Sphere

Valderrama (cf. section 3.2.10). It is a story of endless suffering and great endurance,

mixed with optimism, which contains much unique cultural and anthropologicalinforma-

tion. Among other valuable text material recorded by the aforementioned anthropologists

is a remarkably authentic account of the violent lives of cattle-hustlers from Cotabambas,

Apurimac (Escalante and Valderrama 1992). Howard-Malverde (1981) contains an ex-

tensive collection of myths and stories from Ca˜nar (Ecuador). Weber (1987a) presents a

compilation of the popular Juan del Oso (John of the Bear) stories in different dialects.

Songs, in particular the highly popular huaynos, constitute an element of daily life in

the Andes. Song texts are modified and adapted according to changing circumstances

in the social and political environment. One of the largest anthologies of Quechua song

texts is La sangre de los cerros (urqukunapa yawarnin), compiled by Montoya et al.

(1987).

Few authors have attempted to write contemporary literary texts in Quechua. Even the

bilingual Peruvian author Jos´e Mar´ıa Arguedas (1911–69) wrote his novels in Spanish

and only some poems in Quechua.

3.2.12 Social factors influencing the future of Quechua

If seen as a unity, Quechua is the most widely spoken Amerindian language today. No

wonder that the issue of its future captures the attention of linguists, language planners

and educators both within the Andean region and elsewhere. In spite of the low social

status of Quechua, many inhabitants of Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru are aware of its

native, non-European origin, as opposed to Spanish, once the language of a foreign

colonising power and now of a foreign-oriented ruling class. In 1975, as a result of

agrowing demand for a renewed recognition of national and indigenous values, the

Peruvian military government of Juan Velasco Alvarado issued a decree which put

Quechua on an equal level with Spanish, as the second national language. It was to

remain a symbolic act. The implementation of the decree was largely ineffective, but

it helped to enhance the prestige of Quechua in the eyes of its users. It also generated

agreat deal of discussion on how to secure the future of Quechua and its many local

varieties.

Ever since, the situation in Peru has been marked by a tension between planners

and educators favouring the maintenance and standardisation of the local dialects, on

one side, and those looking for a solution in the sphere of linguistic unification, on

the other. As experts in the Quechua dialect situation (e.g. Torero 1974) observed

that many of the Peruvian varieties were mutually unintelligible, the Peruvian gov-

ernment decided to select six regional standards, Ancash, Ayacucho, Cajamarca, Cuzco,

Huanca and Lamas/San Mart´ın, for which documentation projects were commissioned

(cf. section 3.2.4). This choice was rather artificial in the sense that much dialect diver-

sity existed within the domain of each of the regional standards, in particular Ancash,

3.2 The Quechuan language family 257

Cajamarca, Cuzco and Huanca.

43

Understandably, the regional standards never became

popular, unless they already enjoyed such a status before (Ayacucho, Cuzco).

Rather than government policy, initiatives in the context of international development

cooperation have been relatively successful in supporting and propagating the Quechua

linguistic heritage during the 1980s and 1990s, in particular, the Proyecto Experimental

de Educaci´on Biling¨ue (Experimental Project for Bilingual Education) with its two bases

in Puno and in Quito and, more recently, PROEIB Andes (Programme for Bilingual

Intercultural Education for the Andean Countries) in Cochabamba.

In Bolivia and in Ecuador, where the dialect differences are less outspoken, the devel-

opment of a local Quechua standard may have better prospects than in Peru. In Ecuador

broadcasting programmes in Quechua and a strong native identity feeling, coupled with

a relatively high degree of organisation, have stimulated linguistic unification. For his-

torical reasons standardisation programmes in Ecuador have been independent from

those carried out in Peru and Bolivia. As a result, orthographic usage in Ecuador for a

long time remained different from that in the other two Andean countries. For instance,

whereas the Quechua velar stop was officially written k in Peru and Bolivia, Ecuadorians

followed the Spanish habit of writing qu before the vowels i and e,butc elsewhere.

44

The bilabial continuant, traditionally rendered by means of the combination hu,was

written w in Peru and Bolivia, but not in Ecuador, where it continued to be written hu.

Only since 1998 has the Ecuadorian spelling coincided with the Peruvian and Bolivian

practice (Howard MS).

The issue of how to incorporate conflicting interpretations of the vowel system into

a standard Quechua orthography has been the object of heated debate during the 1980s

and 90s, the central point of contention being whether mid vowels in the environment of

a uvular should be written i, u,ore, o, respectively. An argument frequently advanced

in favour of writing five vowels (a, e, i, o, u) phonetically is that the allophonic vowel

lowering is not entirely predictable; in Cuzco Quechua, for instance, sinqa ‘nose’ is

normally pronounced with a mid vowel [sε

ŋqa], whereas the pronunciation in purinqa

‘he will walk’ varies due to the presence of a morpheme boundary separating the root

from the ending [pur

ŋqa

∼

purεŋqa]. Furthermore, in several present-day Quechua

dialects there are non-borrowed items that have acquired a mid vowel in a non-uvular

43

The Jun´ın–Huanca standard described in Cerr´on-Palomino (1976a, b) presents a synthetic vision

of the Huanca dialects spoken in the Mantaro river valley. Its name suggests that it is also valid for

the Quechua spoken in the northern part of the department of Jun´ın (including the provinces of

Jun´ın, Tarma and Yauli), which differs considerably from the rather innovative Huanca dialects.

As a result, northern Jun´ın is not effectively covered by any of the six regional standards.

44

The Hu´anuco Quechua dictionary of Weber et al. (1998), who use c and qu for the velar stop,

constitutes an exception. Weber (personal communication 2000) notes a strong resistance against

the introduction of k for the velar stop at grassroots level in Peru.

258 3 The Inca Sphere

environment (e.g. Ayacucho Quechua opa ‘dumb’; Santiago del Estero Quechua sera-

‘to sew’).

In spite of all efforts and good intentions, the development of the Quechua language

in Peru (and to a lesser extent in Bolivia and Ecuador) is far from hopeful. Throughout

most of the twentieth century the number of Quechua speakers in Peru remained stable

in absolute terms, whereas the national population was growing explosively. At the

same time, large parts of the country have undergone a language shift from Quechua to

Spanish, mainly along generation lines. The Quechua speakers’ wish for social mobility

for their children is often heard as an argument for not transmitting the language to

the next generation. Bilingualism, seen as an ideal by many language planners, often

proved to be a relatively short station between Quechua monolingualism and Spanish

monolingualism.

Most affected by this process of massive language shift were the Quechua I dialects

of the Central Andes of Peru. If in 1940 the percentage of Quechua speakers in the

highland sector of the department of Jun´ın was still calculated at 75 per cent of the total

population (Rowe 1947), it had fallen to less than 10 per cent in 1993 (Pozzi-Escot 1998:

258). Many varieties of great historical interest, such as (most of) the Huanca dialects

and the dialects of Cerro de Pasco and Tarma, are nearing extinction. Quechua speakers

can still be found among the older generation, but there is little, if any transmission to

the young. At the final stage of the language’s existence most speakers tend to be women

of the eldest generation.

Chirinos Rivera (2001) reports on the distribution of languages in Peru at the distrito

(municipality) level on the basis of data borrowed from the 1993 census. It appears that

even in some of the most Hispanicised areas there are conservative communities which

retain a full use of the Quechua language. Examples are the district of Checras in the

province of Huaura (department of Lima) and the area of Andamarca, Santo Domingo de

Acobamba and Pariahuanca, east of Huancayo and Concepci´on (department of Jun´ın).

In the 1980s and early 1990s, political instability and economic insecurity brought

profound changes to the Peruvian countryside. As a result, entire communities migrated

to urban areas, the Lima agglomeration in particular, as well as other coastal cities. The

department of Ayacucho became the epicentre of violence during this period and lost

25 per cent of its population, mostly through migration. These events were followed by

a process of back-migration between 1995 and 2000 with possible disruptive effects on

the language situation (Chirinos Rivera 2001: 74). Long considered to be a stronghold

of Quechua conservatism, rural Ayacucho and Huancavelica are also feeling the effect

of language shift to Spanish. From the linguistic perspective, the fate of the Quechua-

speaking masses now inhabiting the suburbs and shantytowns of Lima is not known,

but the neighbourhood of centres of Hispanicisation, such as Lima, has never been

favourable for the maintenance of Quechua (cf. von Gleich 1998). As observed quite

3.3 The Aymaran language family 259

adequately by Cerr´on-Palomino (1989b: 27), ‘Quechua (and Aymara) speakers seem

to have taken the project of assimilation begun by the dominating classes and made it

their own.’

3.3 The Aymaran language family

The languages of the Aymaran family (Aymara, Jaqaru and Cauqui) have been studied

somewhat less intensively than those of the Quechuan family with its countless geo-

graphic varieties. However, Aymara itself had the good fortune of being the object of

study of the Italian Jesuit Ludovico Bertonio, one of the most gifted grammarians of

the colonial period. Bertonio wrote two grammars (1603a, b) and a dictionary (1612a),

which are still highly relevant today. Another grammatical description from the colonial

period is Torres Rubio (1616).

In contrast to the name Quechua, there is no likely lexical etymology so far for the

name Aymara (also Aimara or Aymar´a). The term was almost certainly derived from an

ethnonym, the name of a native group occupying the southern part of the present-day

department of Apurimac (now Quechua-speaking). The name of the province of

Aymaraes (capital Chalhuanca), one of the administrative subdivisions of the depart-

ment of Apurimac, reminds us of this historical background.

It is not clear how the name Aymaraes came to be applied to speakers of the Aymara

language in general, but in 1567 it was an established practice, as can be deduced from

Garci Diez de San Miguel’s report of his inspection (visita)ofthe province of Chucuito

(Espinoza Soriano 1964: 14). Garci Diez describes the Aymara of Chucuito, southwest

of Lake Titicaca, as well-to-do cattle-raisers, who were relatively numerous. They shared

the area with the Uro, who were characterised as poor and dependent on fishery.

45

Two

other professional groups, the silversmiths and potters, remain undefined ethnically. For

more discussion of the history of the denomination Aymara see Cerr´on-Palomino (2000:

27–41).

Just as Quechua is also known as runa simi (cf. section 3.2), the Aymara language is

sometimes referred to as jaqi

46

aru ‘language of man’. This denomination is not to be

confounded with that of its smaller relative the Jaqaru language, although, of course,

the two terms share a common etymology.

45

It is tempting to identify the Uros of the historical sources as Uru–Chipaya speakers (cf.

section 3.6). However, modern evidence shows that an Uro way of life depending on fishery and

lake products does not necessarily coincide with a separate ethnic background and linguistic

affiliation. Some typical ‘Uros’, such as the ones inhabiting the islands of the Bay of Puno, are

in fact Aymara speakers. For a detailed treatment of the problem see Wachtel (1978).

46

In the practical orthography developed for the Aymara language the velar fricative or glottal

spirant is represented as j,whereas the uvular fricative is written x (Martin 1988: 25–8, 33). One

should be reminded that Aymara j is the same sound as Quechua h.

260 3 The Inca Sphere

PERU

Canta

Lima

Tupe

Cachuy

Ayacucho

Cuzco

Chalhuanca

CANCHIS

CANAS

Puno

COLLAGUAS

Nazca

Arequipa

Moquegua

Tarata

Tacna

Guallatire

Jopoqueri

CARANGAS

CHIPAYA

Salinas de Garci

Mendoza

Potosí

Morocomarca

Cochabamba

La Paz

Compi

Conima

Oruro

Juli

Sitajara

(Iru-Itu)

Chucuito

San Pedro

de Buenavista

Carumas

BOLIVIA

C

A

U

Q

U

I

J

A

Q

A

R

U

ARGENTINA

BRAZIL

P

A

R

A

G

U

A

Y

C

H

I

L

E

A

Y

M

A

R

A

UCHUMATAQU

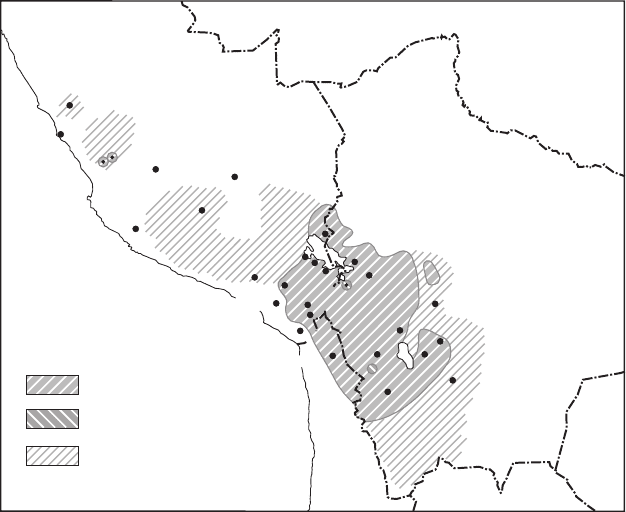

Aymaran languages: AYMARA,

CAUQUI, JAQARU

Uru-Chipaya languages: CHIPAYA,

UCHUMATAQU (Iru-Itu)

Areas where a former presence of

Aymaran languages is attested by

substratum, toponymy or historical

records

Map 6 Distribution of Aymaran and Uru–Chipaya languages

A modern basis for the study of both Aymara and Jaqaru was laid by Hardman and her

team of linguists of the University of Florida. Hardman’s grammatical study of Jaqaru

(1966, 1983a) was followed by a collective work on Aymara (Hardman, V´asquez and

Yapita 1974, 1988). Additional work includes Ebbing (1965) and Porterie-Guti´errez

(1988). For Aymara as well, several language courses (e.g. Herrero, Cotari and Mej´ıa

1978; Yapita 1991) and dictionaries have appeared. Examples of the latter are B¨uttner

and Condori (1984) for Peruvian Aymara; and Cotari, Mej´ıa and Carrasco (1978), as well

as de Lucca (1987) for Bolivian Aymara. The only Jaqaru dictionary so far is Belleza

Castro (1995). The parallel structures of the Quechuan and Aymaran languages are

discussed in Cerr´on-Palomino (1994a). Recent important publications which appeared

after the completion of this section are Cerr´on-Palomino (2000) on the Aymaran family

as a whole and Hardman (2000) on Jaqaru.

3.3.1 Past and present distribution

Some aspects of the distribution of the Aymaran languages have been discussed in

section 3.1. Here we present additional, more specific information.

3.3 The Aymaran language family 261

The original expansion of the Aymaran languages appears to have been comparable

in importance to that of the Quechuan languages, with the difference that it remained

limited to the central and southern parts of the former Inca empire. In northern Peru

and in Ecuador traces of Aymaran presence are sporadic at best. Notwithstanding the

fact that some local groups in Ecuador trace their ancestry back to Aymara-speaking

migrants (mitimaes) brought by the Incas, no substantial influence of Aymara has been

found in their present-day language. The use of ˇcupika,anAymara term for ‘red’, in the

Cajamarca dialect of Quechua is one of the very few documented cases of presumed

Aymara influence in northern Peru.

47

Apart from the three Aymaran languages that survive today, other Aymaran languages,

or possibly dialects of those mentioned before, were spoken in several localities of the

department of Lima until the present century (Canta, Huant´an, Miraflores). The lexicon

of the Quechuan dialect of Pacaraos (province of Huaral, Lima; cf. section 3.2.9) is

strongly influenced by an Aymaran language. The Quechua dialect presumably spoken

in the Lima region, which was described by Santo Tom´as in 1560, also contained lexical

items unequivocally derived from an Aymaran language, e.g. hondoma ‘hot bath’, from

Aymara hunt’(u) uma

48

‘hot water’, ‘a hot drink’ (cf. Torero 1996). Aymaran toponymy is

found in the area of Lima, and also in the Mantaro valley region (department of Jun´ın),

inhabited by the ethnic group known as the Huanca. The manuscript of Huarochir´ı

(cf. sections 3.1, 3.2.11) contains several direct references to Aymaran-speaking groups

in the highland interior of Lima.

As we have seen before, evidence of the existence of Aymaran-speaking groups

throughout the south of Peru can be found in the Relaciones geogr´aficas de Indias of the

sixteenth century (Jim´enez de la Espada 1965). In these Relaciones afew words belong-

ing to the local hahuasimi languages are mentioned (cf. section 3.1). They clearly betray

an Aymaran origin, e.g. cabra ‘llama’ (Aymara and Jaqaru qawra ∼ qarwa); asqui ‘good’

(Aymara aski); cf. Torero (1970), Mannheim (1991). Guaman Poma (1615) specifically

refers to some Aymara-speaking areas, such as the highlands surrounding Pampachiri in

the province of Andahuaylas, and parts of the Huanca region. He, furthermore, provides

a number of Aymaran song texts, which have been analysed by Alb´o and Layme (1993;

forthcoming) and by Ferrell (1996). The latter author shows that Guaman Poma’s Aymara

47

One of the arguments advanced by Middendorf (1891b) in favour of the former presence of

Aymara in northern Peru is the frequent use of place names containing the element wari (as in

Huari, a town and province in Ancash). Wari means ‘vicu˜na’ in Aymara. However, wari was also

the name of the central deity in a religious cult situated in the central and northern highlands

of Peru. A relationship with Panoan wari or bari ‘sun’ has been suggested (Torero 1993b:

224).

48

The shape of this expression suggests contact with Aymara itself, not with one of the Aymaran

languages spoken in the province of Yauyos. These have hunˇc

.

’u, rather than hunt’u for

‘hot’.

262 3 The Inca Sphere

wasaseparate linguistic variety, not to be confounded with any of the languages spoken

today. He calls it Aimara ayacuchano (‘Ayacucho Aymara’), considering that Guaman

Poma was a native of the Lucanas region in the south of the department of Ayacucho

(Ferrell 1996: 415).

49

It is not certain to what extent Aymaran languages (or even Aymara) were dominant

in all of southern Peru, but their presence in at least some areas is hardly a matter of

discussion. One such area was the region of Collaguas (see section 3.1). Aymara to-

ponymy can also be found elsewhere in the Arequipa region, for instance, in the name

of some of Arequipa’s townships, e.g. Umacollo (uma qul

y

u)‘water-hill’, or of neigh-

bouring mountains, e.g. Chachani (ˇcaˇcani) ‘mountain of man (or male)’, Anuccarahui

(anuqarawi) ‘dog’s meeting place’. Toponyms of unmistakable Aymara origin can also

be found in the area of Cuzco, in particular, to the southeast of that city in the provinces

of Canas and Canchis, e.g. Tungasuca (tunka suka) ‘ten furrows’, Checacupi (ˇc’iqa kupi)

‘left and right’, Vilcanota (wil

y

ka-n(a) uta) ‘house at/of the sun’.

Aymara substratum is strongly present in the lexicon and the morphology of Quechua

dialects spoken in the departments of Puno and Arequipa. The Aymara influence is very

specific and includes the use of verbal derivational suffixes with their respective vowel-

suppression rules, albeit in an attenuated form (cf. Adelaar 1987; Chirinos and Maque

1996). This influence can only be explained by assuming a relatively recent language

shift from Aymara to Quechua after extensive bilingualism. It cannot be attributed to

borrowing alone.

An intertwined situation of Quechuan- and Aymaran-speaking groups can be recon-

structed for large areas of central and southern Peru, mostly areas where today only

Quechua survives (cf. Mannheim 1991). Close contact between Quechua and Aymara

speakers in situations where the use of either language has become linked to a partic-

ular social division or economic activity has been found in the Bolivian department

of La Paz north of Lake Titicaca. In these situations of language overlapping, either

Quechua may hold a higher prestige than Aymara, or the other way round; see Harris

(1974), cited in Briggs (1993: 4). Recent findings, e.g. near San Pedro de Buenavista,

province of Charcas, Potos´ı, suggest that not all Aymara-speaking communities sur-

rounded by Quechua speakers have been identified so far (cf. Howard-Malverde 1995).

A meticulous account of the distribution of Aymara and Quechua speakers in Bolivia

in the 1990s (including detailed maps) can be found in Alb´o (1995). The maps which

are provided distinguish between areas where Aymara has been predominant tradition-

ally, areas of colonisation, areas where Aymara is giving way to either Quechua or

Spanish, etc.

49

Ferrell considers Ayacucho Aymara to be a manifestation of an alleged, more comprehensive

Cuzco Aymara. The reason for this classification remains unclear.

3.3 The Aymaran language family 263

3.3.2 Homeland and expansion

The more than usual intensity of past language contact, as attested by Aymaran and

Quechuan, indicates that the proto-languages of both groups were spoken either in

contiguous areas, or in the same area in a situation of geographic intertwining (cf.

section 3.1). Since the homeland of the Quechuan languages has been assigned to the

coast and sierra of central Peru, the Aymaran homeland could not have been located too

far from it. And, as the Aymaran expansion, subsequently, went south, not north, it made

sense to look for an Aymaran homeland immediately to the south of that of Quechua.

Following this line of reasoning, Torero (1970) tentatively assigned Proto-Aymaran to

the coastal civilisation of Nazca and the interior Andean region of Ayacucho. At the same

time, he allowed for some overlapping in the province of Yauyos (department of Lima),

where archaic varieties of Aymaran and Quechuan have co-existed until the present day.

The geographic configuration delineated above is not incompatible with the alternative

hypothesis of an original Aymaran homeland further north, in the heart of central Peru

itself. This scenario would imply a partial displacement of the Proto-Aymaran population

by Quechuan speakers somewhere at the beginning of the present era. It is favoured by

the large number of Aymaran place names and borrowings in central Peru and the

intense contact that we must assume to have existed between the two language groups.

The subsequent expansion of Aymaran-speaking peoples, which may have taken place

between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, could have occurred either on their own

initiative, or under the pressure of Quechua-speaking people coming from the north.

The situation of dominance which the Aymara held in the Bolivian highlands until

1600 has already been mentioned. A comparison of the colonial evidence (Bouysse-

Cassagne 1975) with the present-day distribution of the Andean languages clearly shows

that Aymara must have become superseded by Quechua in large parts of the southern and

eastern highlands of Bolivia during the last four centuries. A similar process took place

in many parts of southern Peru. On their way south the Aymaran languages occupied the

place of other, previously present languages. For instance, in the central-eastern part of

the department of Moquegua (province of Mariscal Nieto, around the communities of

Carumas, Calacoa and Cuchumbaya) and in some areas north of Lake Titicaca Aymara

replaced local varieties of Puquina. However, since the beginning of the colonial period,

no further expansion of importance has been reported. Probably as a result of their

more homogeneous background, the present-day Aymara have developed a strongly

articulated ethnic identity, in contrast with most of the Quechua-speaking peoples that

surround them. The latter largely originated from different ethnic groups that became

Quechuanised.

At the arrival of the Spaniards, most of the Aymara were organised in chieftaincies,

some of which had succeeded in retaining a certain autonomy in spite of their subju-

gation by the Incas (cf. Tschopik 1946). Of particular historical importance was the