Yi Lin. General Systems Theory: A Mathematical Approach

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 5

A Theoretical Foundation for the Laws

of Conservation

Finite divisibility of general systems is shown. Based upon this result, Lavoisier’s

Axiom, introduced in 1789, is verified by using the concept of fundamental par-

ticles, where a fundamental particle is one which can no longer be divided into

smaller ones. The conservation principle of ancient atomists is recast and proved

mathematically, based on which the law of conservation of matter–energy can

be seen clearly. A brief history of atoms, elements, and laws of conservation is

given, and some important open questions are posed. This chapter is based on

(Lin, 1996).

5. 1.

Introduction

In the rest of this section, we briefly list some basic terminology and concepts

to fully understand the discussion in Section 5.2.

According to Cantor, the creator of set theory, the word “set” means a collection

of objects (or elements). However, such a view is untenable, as in certain cases the

intuitive concept has been proved to be unreliable. So, in axiomatic set theory the

theory is based on a system of axioms (usually on the system of ZFC axioms), from

which all theorems are obtained by deduction. “Set” is one of the two primitive

notions of the theory and is not examined directly about its meaning.

The law of conservation of matter–energy, one of the greatest achievements

of all time, and systems, a current fashionable concept in modern science and

technology, are joined under the name of general systems theory. Research in the

foundation of mathematics, named set theory, has found its way through general

systems theory into the realm of scientific activities related to the search for order

of the natural world in which we live. The goal of this chapter is to establish a

rigorous theoretical frame-work for the part of the world of learning on the laws

of conservation. Hopefully, this study will provide an early casting of a stone to

attract many beautiful and useful gems in future research along the line described

here.

111

112

Chapter 5

The ZFC axiom system is the Zermelo–Fränkel system with the axiom of

choice. For details, refer to (Kunen, 1980; Kuratowski and Mostowski, 1976). For

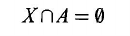

convenience, we state the Axiom of Regularity, one of the ZFC axioms: If

A

is a

nonempty set of sets, then there exists a setX in A

such that

5.2. Brief History of Atoms, Elements, and Laws of

Conservation

All mathematical results, introduced in Section 5.2, are based on the assump-

tion that the system of ZFC axioms is consistent, denoted by Theorem (ZFC). That

is, the theory derived from ZFC axioms does not contain contradictory statements.

Let x and y be two sets. The set {{x

}, {

x

,

y}} is called an ordered pair, denoted

by (

x

,

y ). The first term of (x,

y

) is

x, and the second term is y. For details, see

(Kuratowski and Mostowski, 1976).

The concept of systems, used in the following discussion, was first introduced

in (Lin, 1987). It generalizes those concepts introduced by Whitehead (1978),

Tarski (1954–1955), Hall and Fagen (1956), Mesarovic and Takahara (1975), and

Bunge (1979). The definition reads as follows:

S is a (general) system, if S equals

an ordered pair (M

,

R

) of sets, where

M is the set of objects and R is a set of some

relations on M. The sets M and

R

are called the object set and the relation set of

S, respectively. (For those readers who are sophisticated enough in mathematics,

a relation

r

in R implies that there exists an ordinal number

n

=

n

(

r

), a function

of r, such that r is a subset of the Cartesian product of n copies of the set M

.)

The countless ideas in thousands of volumes in a library are arrangements of

26 letters of the alphabet, 10 numerals, and a few punctuation marks. Because

of this and similar observations, the great thinkers throughout the history have

been wondering whether the rich profusion from objects around us are formed of

a basic alphabet of nature itself in various combinations? If so, what would be the

characteristics of nature’s “building blocks”?

The ancient Greeks were intrigued by the diverse, changing, temporary char-

acter of objects around them. But they were confident that the universe is one, and

they looked for something unifying and eternal in the variety and flux of things.

In the search for order, the one-element Ionians (624–500 B.C.) had a naturalis-

tic and materialistic bent. They sought causes and explanations in terms of the

eternal working of things themselves rather than in any divine, mythological, or

supernatural intervention. Looking for a single basic reality, each Ionian believed

that all things have their origin in a single knowable element: water, air, fire, or

some indeterminate, nebulous substance.

A Theoretical Foundation for the Laws of Conservation

113

The four-element philosophers, including Empedocles (490–435 B.C.),

Pythagoras and his followers (from 5th century B.C. on), Philolaus (480 B.C.–

?), Plato (427–347 B.C.) and Aristotle (384–322 B.C.), claimed that there is not

one basic element but four: earth, water, air, and fire. The Egyptians had long

recognized four elements with qualities of male or female. For example, earth is

male when it has the form of boulders and crags; female when it is cultivable land.

When air is windy, it is male; when cloudy or sluggish, female. The Chinese,

as early as the 12th century B.C., had five elements, the previous four and wood,

together with five virtues, tastes, colors, tones, and seasons.

Among his physical ideas of matter, Aristotle introduced a fifth element. This

element cannot be “generated, corrupted, or transformed.” This pure, eternal, ethe-

real substance makes up the heavens and all their unchangeable objects. Beneath

the lunar sphere, the many products of the terrestrial four elements ceaselessly

transform. He pointed out that, although all substances of the four elements are

individually “generated, corrupted, and transformed, the universe as a whole is

ungenerated and indestructible.” Thus, in him a conservation of matter concept

can be found.

Anaxagoras (510–428 B.C.) in his “seeds” idea was unwilling to submerge

the tremendous varieties in things into any common denominator. He preferred

to accept the immediate diversity of things as is. With his philosophy, every

object is infinitely divisible. No matter how far an object is divided, what is left

would have characteristics of the original substance. That brings us to the very

interesting question of the transformation of matter. If all substances are derived

from unique seeds of themselves, how can one substance develop into another?

The contribution of Anaxagoras’ concept of seeds was its refinement, its idea

of taking substances as they are and breaking them down minutely in order to

know more about them. One main weakness of the concept is passing down the

complexities of a large-scale object to unseen miniatures of itself. Since these

miniatures were infinitely divisible, a fundamental unit was lacking.

The Leucippus–Democritus atom (500–55 B.C.) combined features of the

Ionian single element, Anaxagoras’ seeds, and Empedocles’ four elements and yet

was an improvement over all of them. “Atom” means “not divisible” in Greek.

This term was intentionally chosen by Democritus to emphasize a particle so small

that it could no longer be divided. To Leucippus and Democritus, the universe

originally and basically consisted entirely of atoms and a “void” in which atoms

moved. Eternally, the atom is indestructible and unchanging. Atoms are all of the

same substance, but by their various sizes and shapes, they can be used to explain

the large variety of objects they compose. Individual atoms, solid, eternal, and

indestructible, always maintain their identity in uniting or separating. It is the union

and separation of atoms that is temporary and that results in the transformation of

objects. The result is the principle of conservation of matter: Matter is neither

created nor destroyed but is transformed. However, after the atomists, the idea

of Plato and Aristotle on the nature of matter might seem almost an anticlimax.

114

Chapter 5

Without the introduction of experimentation or the refinements of measurement,

the Greek atomic theory, as it turned out, did not have a chance against the authority

of Plato and particularly that of Aristotle. However, experimental techniques and

knowledge had not yet reached the point where they could prevent the atomists

from being eclipsed by Aristotle — and experimental techniques and knowledge

are social accumulations. That is why we need to develop the fundamental theory

and understanding about the existence and feasibility of the modern concept of

elements and particles.

Men search for order through a few unifying principles, but nature has a way

of seeping through categories set for it. Meanwhile, men gain detailed knowledge

of their surroundings and develop more sophisticated concepts, techniques, and

unifying principles. Experiments, becoming respectable in the Scientific Revolu-

tion, eventually showed that earth, water, air, and fire can be resolved into simpler

substances and that the Aristotelian elements are not elements after all, or that they

are more appropriate as states of matter that apply to every substance.

Bacon and Galileo had accepted the Greek idea of atoms. D. Sennert, a German

physician, had applied atomic theory to specific natural processes. P. Gassendi,

influential French mathematician and philosopher, developed an extensive non-

mathematical atomic theory. Boyle, a founder of the British Royal Society, was

among the first serious experimenters of the Scientific Revolution to use atoms

to explain specific experiments. His contemporary Newton used a corpuscular

theory to explain his investigations of light.

To ancient atomists, the total count of atoms in the universe was constant. The

total amount of matter, therefore, remained the same regardless of changes. The

atomists had a conservation principle of matter. In 1789, Lavoisier abstracted from

his laboratory observations a law of conservation of matter: All matter existing

within any closed system constitutes the universe for a specific experiment, where

a “closed” system is one in which outside matter does not enter and inside matter

does not leave. According to William Dampier, in 1929, “Because of its practical

use, and for its own intrinsic interest, the principle of conservation of energy may

be regarded as one of the great achievements of the human mind.” Let us now take

a brief look at the development of the conservation law of energy.

Heat of friction was the Achilles’ heel of the caloric theory. Rubbing two

blocks of wood together, makes the surfaces warmer. Why? From where does

this heat of friction come? The calorists theorized that heat fluid is squeezed out

from the interior of the blocks. That is, caloric is neither created nor destroyed; it

is merely forced to the surface by friction.

Count Rumford (1753–1814) denied the calorists’ theory, as he supervised

the boring of cannon. Sir Humphrey Davy (1778–1829) corroborated Rumford

by rubbing two pieces of ice together. Ship’s Surgeon J. R. Mayer (1814–1878)

speculated that the calorists were wrong while observing venous blood color in

different climates. And J. P. Joule (1818–1889) argued against it as his paddles

vigorously stirred water in calorimeters. All these men claimed evidence that heat

A Theoretical Foundation for the Laws of Conservation

115

of friction is heat produced by motion, that heat is a form of motion (energy), not a

form of matter. Conversely, Watt’s steam engines, invented in 1763, transformed

heat into mechanical energy. The ancient Chinese invented gunpowder and used it

in rockets. Europeans of the Middle Ages used the powder to propel musket shot

and cannonballs. Actually, a gun is an engine that converts the heat and expansive

force of an explosion into mechanical motion. So, by Joule’s time, conservation

of energy as a broad principle was in the air.

Some limited aspects of the broad principle appeared as follows: Newton’s

law of action and reaction led to conservation of momentum. Huygens proposed

a conservation of kinetic energy for elastic collisions. Work concepts and swing-

ing pendulums led to a principle of conservation of mechanical energy and to

efforts toward perpetual-motion machines. Black took seven-league steps with

his conservation of heat principle. Experiments by Rumford and Davy pointed to

heat as a form of energy, and Joule established a quantitative connection between

mechanical energy and heat through persistent, precise techniques.

What remained was for someone with enough insight, interest, and imagination

to put the pieces together and present the whole picture. This was what the German

physician J. R. Mayer (1814–1878) did, later reinforced by the technical language,

mathematical rigor, and pointed applications of his countryman H. von Helmholtz

(1821–1894), a famous biophysicist.

Chemistry was based on the law of conservation of matter. Physics was based

on the law of conservation of energy. It has been shown however that matter

transforms into energy, and energy into matter. Now hen what? Where is the

constancy of matter or energy? What happens to the indispensable “=” signs in

the equations of physicist and chemist? What happens to physics and chemistry

as “exact” sciences? Einstein combined the two conservation laws into one, a law

of the conservation of matter–energy: The total amount of both matter and energy

is always the same.

For a more detailed and comprehensive history, please refer to Perlman’s work

(Perlman, 1970).

5.3. A Mathematical Foundation for the Laws of

Conservation

From the discussion in the previous section, it can be seen that all these laws

of conservation were established based on experiments or intuitive interpretations

of some related experimental results or simple observations. In this section some

mathematical results of general systems theory are introduced and used to establish

a theoretical foundation for the laws of conservation. The models or understanding

of the laws of conservation used in this section may not be those currently accepted

by research physicists or chemists, but they are surely some of the major steps

116

Chapter 5

(5.1)

along the path leading to the current ones. By doing so purposely, I hope that a

greater audience can be reached.

A system S

n

= (

M

n

,

R

n

) is an nth-level object system (Lin and Ma, 1987) of

a system S

0

= (

M

0

,R

0

) if there exist systems

S

i

=

(M

i

,

R

i

), for

i

= 1, 2, . . . ,

n

– 1,

such that the system S

i

is an object in M

i

-1

, 0 <

i < n + 1. Each element in M

n

is called an nth-level object of S

0

. A chain of object systems of a system S is a

sequence {

S

i

: i < α

}, for some ordinal number

α

, of different-level object systems

of S, such that for each pair i

,

j < α with i < j, there exists an integer n = n (i,j),

which depends on the ordinal numbers i and j, satisfying that the system S

j

is an

nth-level object system of S

i

. Then we can prove the following result.

Theorem 5.3.1 [ZFC]. Suppose that S is a system. Then each chain of object

systems of S must be finite.

Proof: For the sake of completeness of this chapter, a proof of this result is

given. It is not intended for general audiences but for a few readers who have the

adequate mathematical background. The theorem will be proven by contradiction.

Suppose that there exists a chain of object systems of infinite length, such

as {S

i

= (

M

i

,

R

i

) : i = 1, 2, 3, . . . }, satisfying that S

i

is an object of the system

S

i–

1

,

i=

1, 2, 3 , . . . . Now define a set

X

as follows:

From the Axiom of Regularity (Kunen, 1980), it follows that there exists a set Y

in X such that

There are now three possibilities: (1) Y = M

i

, for some i = 1, 2, . . . ; (ii) Y = S

i

,

for some i = 1, 2, . . . ; and (iii) Y = {M

i

}, for some i = 1, 2, . . . . If (i) holds,

This contradicts Eq. (5.1). So, the possibility (i) cannot be true.

If (ii) holds, Y = S

i

= (

M

i

,

R

i

) = {{

M

i

}, {

M

i

,R

i

}}. That is,

This contradicts Eq. (5.1). Hence, (ii) cannot be correct. If (iii) holds, M

i

∈

, again a contradiction of Eq. (5.1). Therefore, (iii) cannot be true.

These contradictions show that the assumption of a chain of object systems of

infinite length cannot be correct.

As introduced by Klir (1985), a system is what is distinguished as a system.

We then can do the following general systems modeling: For each chosen matter,

real situation problem, or environment, such as a chemical reaction process, a

system, describing the matter of interest, can always be defined. For example,

let S = (M

,

R) be a systems representation of a chemical reaction process, such

that M stands for the set of all substances used in the reaction and R is the set

A Theoretical Foundation for the Laws of Conservation

117

of all relations between the substances in M. It can be seen that S represents the

chemical reaction of interest. Changes of S represents changes of the objects in

M and changes of relations in R. Based upon this understanding and by virtue

of Theorem 5.3.1, it follows that we have proven theoretically Lavoisier’s Axiom,

given in 1789.

Axiom 5.3.1 [Lavoisier’s Axiom (Perlman, 1970, p. 414)].

In all the operations of art and nature, nothing is created! An equal quantity of

matter exists both before and after the experiment . . . and nothing takes place

beyond changes and modifications in the combination of the elements. Upon this

principle, the whole art of performing chemical experiments depends.

In brief, this conservation law says that all matter existing within any closed

system constitutes the universe for a specific experiment. That is, if S = (

M,R

) is

the systems representation of a chemical reaction defined as before, then a chemical

reaction between the substances in M is just simply a change and modification of

some relations between the fundamental particles. Here, a fundamental particle

is a particle which can no longer be divided into smaller ones. The existence of

fundamental particles is shown by Theorem 5.3.1, since if a particle A can still be

divided into smaller particles,

A

then can be studied as a system, based upon Klir’s

definition of systems. Theorem 5.3.1 says that each chain of object systems must

stop; i.e., each particle must be finitely divisible.

Based upon this understanding, the conservation principle of ancient atomists

(Perlman, 1970, p. 414), which states that the total count of atoms in the universe

is constant; therefore, the total amount of matter remains the same regardless of

changes, can be restated as follows:

Law [Conservation of Fundamental Particles]. The total count of basic parti-

cles in the universe is constant; therefore, the total amount of matter remains the

same regardless of changes and modifications.

A brief reasoning for the feasibility of this law is the following: There are three

basic known changes in the universe: physical, chemical, and nuclear. A change

in which a substance entirely retains its original composition is a physical change.

A change in which a substance loses its original composition and one or more new

substances are formed is a chemical change. A change where nuclei, which are

unstable, shoot out “chunks” of mass and energy, and other changes, while take

place in the nucleus of an atom, are called nuclear reactions. None of these changes

is a change at the fundamental particle level. Rather each is a recombination of

some higher level systems of the fundamental particles. At the same time, the

following theorem guarantees that for each given system S = (

M,R

), the set of

fundamental particles is uniquely determined. Hence, if the physical universe

is studied as a system, the set of basic particles is eternal, indestructible, and

unchangeable. It, in turn, proves the feasibility of the Law of Conservation of

Fundamental Particles.

118

Chapter 5

Theorem 5.3.2 [ZFC]. For each system S = (

M

,

R

)

, the set of all fundamental

objects are unique.

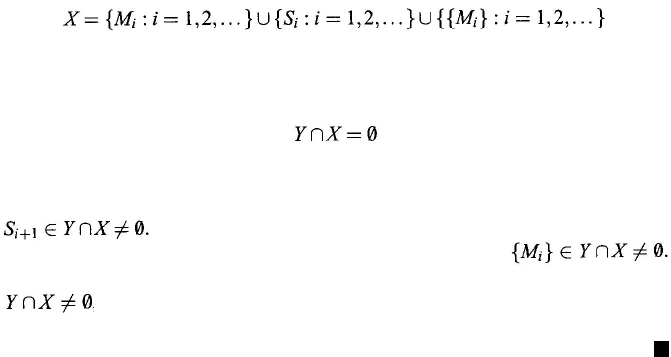

Proof: Again, the proof given here is for completeness of this chapter. Let

M

1

= {m ∈ M : m is not a system}

and

By mathematical induction, assume that all sets M

i

and M

*

i

have been defined for

each i < n + 1 for a natural number n satisfying

M

i

= {m ∈ M

*

i

– 1

:

m

is not a system}

and

Then M

n

+ 1

and M

n

+ 1

*

can be defined as follows:

M

n

+ 1

= {

m

∈

M

*

n

:

m

is not a system}

and

Theorem 5.3.1 guarantees that there is a natural number n such that M

j

and M

*

j

equal

φ, for all j > n + 1. Thus, the set

consists of all fundamental objects of the system S and is unique, since each set

M

i

is uniquely defined.

Let us discuss some impacts of what has been done on the Law of Conservation

of Matter–Energy. The law states that the total amount of matter and energy

is always the same. Historically, this law was developed based upon the new

development of science and technology: Energy and matter are two different

forms of the same thing. That is, matter can be transformed into energy, and

energy into matter. Each matter consists of fundamental particles, and so does

energy. Since energy can be in different forms, such as light, it confirms that each

fundamental particle has no volume or size. Actually, Theorem 5.3.1 also proves

this fact, because if a particle has certain a volume, it would be possible to chop it

up into smaller pieces. That is, the particle can be considered a system; it is not

a fundamental particle. As a consequence of the Law of Conservation of Basic

Particles, the Law of Conservation of Matter–Energy becomes clear and obvious.

A Theoretical Foundation for the Laws of Conservation

119

5.4. A Few Final Words

In the previous mathematical analysis of the laws of conservation, many impor-

tant questions are left open. For example, it is necessary to develop conservation

equations in terms of fundamental particles and to write them in modern symbolic

form. Only with the indispensable “=” signs in the equation can the theory, devel-

oped on the law of conservation of fundamental particles, be made into one “exact

science” with the capacity of prediction.

It took several thousand years to develop the Law of Conservation of Matter–

Energy. The law has been considered as one of the greatest syntheses of all

time, comparable to those of Ptolemy and Newton. Without the “=” signs of

the conservation laws, certainly modern physics, chemistry, and technology could

hardly exist. Not only this, the great idea, contained in the conservation law,

contradicts the common notion that all things must change. This idea is still

developing. The full range of its implications is not yet clear, but surely the

consequence will be revolutionary.

CHAPTER 6

A Mathematics of Computability that

Speaks the Language of Levels

In this chapter we use the modern systems theory to retrace the history of

important and interesting philosophical problems. Based on the discussion, we

show that the multilevel structure of nature can be approached by using the

general systems theory approach initiated by Mesarovic in the early 1960s.

Two difficulties appearing in modern physics are listed and studied in terms

of a new mathematical theory. This theory reflects the characteristic of the

multilevel nature. Some elementary properties of the new theory are listed.

Some important and fruitful leads for future research are posed in the final

section.

6.1. Introduction

Since the concept of systems was first formally introduced by von Berta-

lanffy in the 1920s, the meaning of system has been getting wider and wider.

As the application of the systems concept has become more widespread, the

need to establish the theoretical foundation of all systems theories becomes

evident. To meet the challenge of forming a unified foundation of the theory

of systems, Mesarovic and Takahara introduced a concept of general systems,

based on Cantor’s set theory, in the 1960s. Since the theory of general systems

has been established on set theory, one shortfall of this “theoretical foundation”

is that it is difficult or impossible to quantify any subject matter of research.

In this chapter recent results in general systems theory are used to show the

need for a mathematical theory of multilevels, and, based on Wang’s work

(1985; 1991), one is introduced. This theory is used to study two problems

in modern physics. Hopefully, this work will make up the computational

deficiency of the current theory of general systems.

121