Water Power and Dam Construction. Issue September 2010

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

&OHDQ(QHUJ\

IRURXUIXWXUH

0DQQYLWDQG9HUNtVDUHOHDGLQJH[SHUWVLQ+\GURSRZHU

:HSURYLGHFRQVXOWLQJVHUYLFHVIRUDOODVSHFWVRI

+\GURSRZHUSURGXFWLRQDQGSRZHUGLVWULEXWLRQIURP

IHDVLELOLW\VWXGLHVWRIXOO\RSHUDWLQJSRZHUV\VWHPV

%RWKFRPSDQLHVWDNHSULGHLQFUHDWLQJDEHWWHUIXWXUH

WKURXJKWHFKQRORJ\IRUWKHHQYLURQPHQWDQGIXWXUH

JHQHUDWLRQV

0DQQYLWDQG9HUNtVKDYHRYHU\HDUVRIH[SHULHQFHDQG

DFRPELQHGZRUNIRUFHRIVSHFLDOLVWV

<RXDUHZHOFRPHWRYLVLWXVDWVWDQGQUGXULQJWKH

FRQIHUHQFH

ZZZPDQQYLWFRPZZZYHUNLVFRP

62 SEPTEMBER 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

RESEARCH

B

UILT in 1966 the South Fork Rivanna reservoir and dam

are located in the US state of Virginia. Along with the

Sugar Hollow, and Upper and Lower Ragged Mountain

reservoirs, the facilities are operated by the Rivanna Water

and Sewer Authority (RWSA). They supply drinking water and

treat sewage in designated areas of Albermarle County.

Water demand within the urban service area is fast approaching

the safe yield of water supplies contained within the three reservoirs.

Consequently RWSA is pursuing its Community Water Supply Plan

(CWSP) to ensure that adequate drinking water is available over the

next 50 years.

After many years of studies, consultation and public involvement,

Gannett Fleming Engineers and Vanassae Hangen Brustlin assisted

RWSA with the development of the nal plan. The essence of which

was to expand the existing Ragged Mountain reservoir to provide

a ve-fold increase in raw water storage within this system. In addi-

tion a raw water pipeline from South Fork Rivanna reservoir will

facilitate the transfer of water to the enlarged Ragged Mountain

facility. These were considered as the least environmentally damag-

ing and practicable alternatives to safeguard future water supplies.

However, in 2009 the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir Stewardship

Task Force requested that RWSA undertake a study of the reservoir.

This was to assess whether options such as dredging and siltation

prevention could maintain and enhance the aquatic health and water

quality of the facility. The aim is to ensure that the reservoir remains a

long-term, valuable water resource for the benet of the community.

This is in addition to the CWSP, which left the idea of dredging open

as a benet to recreational or water quality benets for the South

fork reservoir, but did not recommend dredging as the solution to the

future water supply need.

BUILDING UP

Since it was built South Fork Rivanna reservoir has lost 22% of total

water supply volume above the water intake elevation of 112m.

Sedimentation is the root of the problem.

River ow into the reservoir is from a drainage area of approx

668km

2

. Large portions of this are forested (73%). The majority of

the remainder is agriculture, with developed areas making up almost

half of the remaining total. Soil erosion from natural events; from land

use in the agricultural area; from land disturbances in the developed

areas; and from re-suspension of ood plain deposits created during the

19th century (stream bank erosion), are the likely causes of signicant

amounts of sediment becoming trapped within the reservoir.

With the approved water supply plan, and without additional

community funds for dredging, the task force fears that the benets

of South Fork reservoir to the community will diminish. Although

Ragged Mountain will serve as the major water storage facility once

expanded, some argue that there will still be short-term storage

capacity benets that South Fork can full until completion of the

expansion in 2021. The suggestion is that a modest level of reservoir

dredging will make this possible.

DREDGING STUDIES

In October 2009 HDR Engineering was awarded a US$344,000

contract by RWSA to assess the feasibility of restoring water supply

capacity at South Fork Rivanna reservoir. Its aim is to bring capacity

as near to its original contours and water storage volume as practical,

through the removal of accumulated sediment.

Restoring the reservoir to its original levels would require removal

of approximately 1.3Mm

3

of deposited material. However dredging

the entire reservoir is not practical: it is not recommended in sensi-

tive wetlands, vegetated islands, or close to bridges or steep banks

along the shoreline. Subtracting these recommended no-dredge areas

reduces the total estimated dredging volume.

Dredging 860,000m

3

would restore all of the useable water supply

volume plus 56% of the water supply volume below the water intake

elevation of 112m in the Upper Main Stem and Ivy Creek portions

of the reservoir. Overall, a dredging volume of 860,000m

3

represents

79% of the 1Mm

3

maximum dredging target and 65% of the total

deposited material.

HDR has identied a two-part dredging approach to reach the

favourable 860,000m

3

dredging volume:

r Part I would dredge reservoir segments 1-3 (the uppermost portion

of the Upper Main Stem), dewater the sediment using mechanical

dewatering equipment, and sell or reuse the recovered materials to

off-set the cost of dredging.

r Part II would dredge reservoir segments 4–9 (the remainder of the

Upper Main Stem) and/or Ivy Creek and dewater the sediment

using three conned dike facilities. Dredged sediments removed in

Part II would remain in the conned dike facilities and there would

be no recovery of material.

The two part dredging approach could be conducted simultaneously

or in sequence, depending on available resources.

FULL OF CHARACTER

Part of HDR Engineering’s investigations also focused on a sedi-

ment characterisation study of the reservoir; determining what type

Is dredging the solution to sedimentation problems at South Fork Rivanna reservoir in

the US? The answer isn’t as clear-cut as it seems. Suzanne Pritchard reports

The dredging option

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

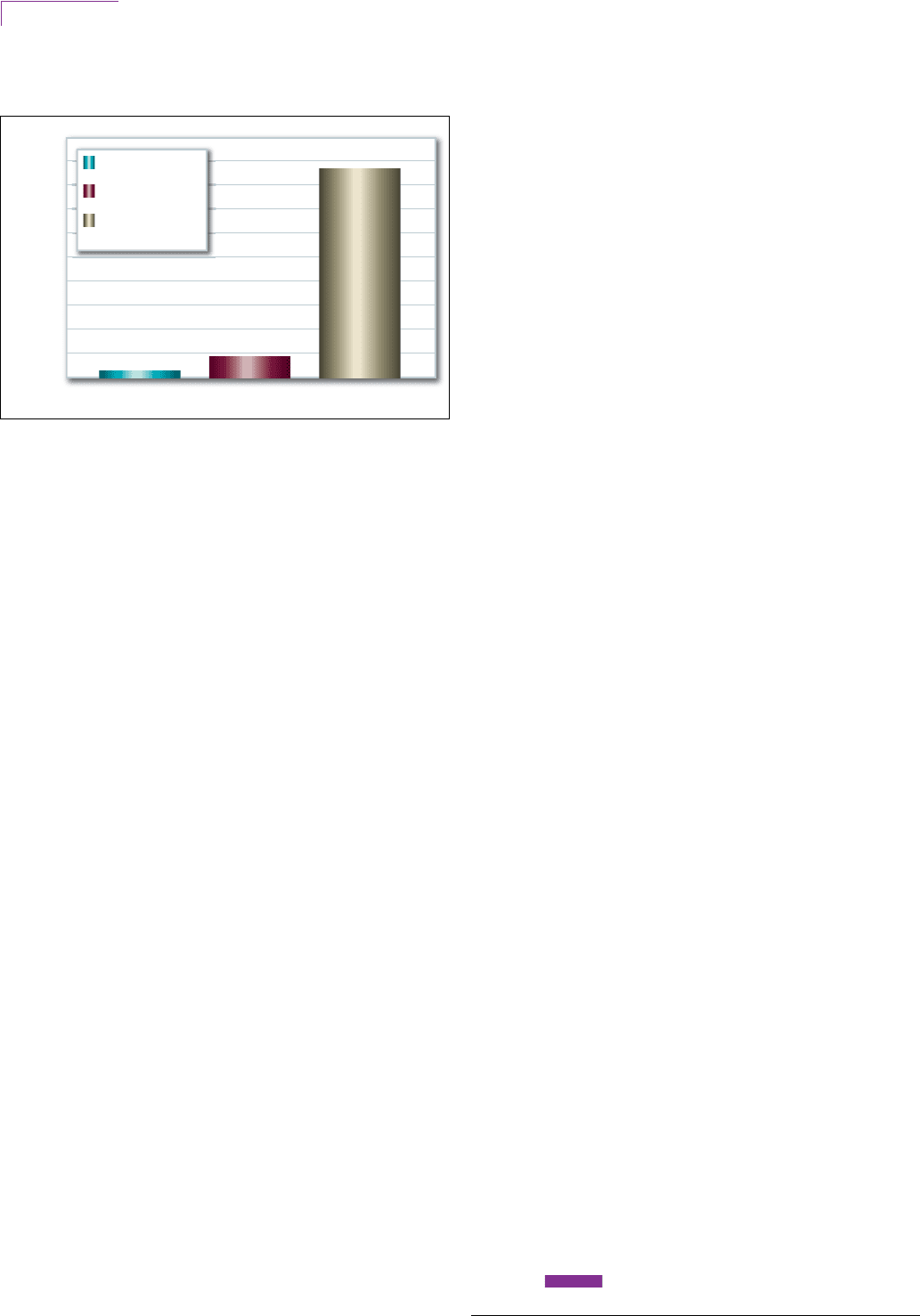

Cost ($) per cubic yard

Mid-point of cost per cubic yard

Dredging Part I

Dredging Part II

Ragged Mountain

Reservoir

Graph showing cost per cubic yard of water storage added

A subscription to one of the above titles will deliver

• A full colour magazine every month

• Regular industry e-mail newsletter

• Full acces s to online archives

• Free industry dire ctory

Subscribe online at:

or call our subscriptions hotline on:

+44 845 155 1845

email: cs@ progressivemediagroup.com

Individual focus,

Subscribe Now

to one of our

power magazines!

combined power

Global Trade Media

Progressive House 2 Maidstone Road Foots Cray Sidcup Kent DA14 5HZ, UK

WWW.MODERNPOWERSYSTEMS.COM SEPTEMBER 2010

Fuel cell technology

CCS – a new role for the

molten carbonate fuel cell

?

IGCC

From Polk to Edwardsport:

twenty years of evolution

Puertollano captures a

world first

Combined cycle

Capture ready CCGT:

what does it really mean?

Nuclear power

UAE takes the next steps,

while Koreans look to APR+

Renewables

European offshore wind:

outlook fair to good

Navigating the hazards

of offshore consenting

Putting marine energy

on trial in Scotland

Gas turbine

technology

Using membranes to filter

out compressor problems

Recips

Diesel gensets take off at

Larnaka

COMMUNICATING POWER TECHNOLOGY WORLDWIDE

ModernPowerSystems

Testing time for

tidal turbines

Exploring Power Plant Emissions

R

eduction – Technologies and

Strategies

www.arena-international.com/expperts2010

Berlin, Germany

27-28 September 2010

EXPPERTS

2010

JULY 2010

Serving the hydro industry for over 60 years

Tackling sediment at dams

Small hydro renaissance

Tackling sediment at dams

Pushing ahead

Progress reports on hydro tunnel projects

INTERNATIONAL

& DAM CONSTRUCTION

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM

JULY 2010

& DAM CONSTRUCTION

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM

Water Power

www.neimagazine.com September 2010

Stretching fuel to the limit

Competition for long-term uranium supply rises page 15

After 2020, conversion supply will not meet demand page 22

World enrichment capacity depends on four new plants page 26

Fuel vendor design data for the main reactor types page 30

How to audit fuel vendors: a guide for utilities page 41

Debris and calculation errors cause most fuel failures page 48

www.waterpowermagazine.com

www.neimagazine.com

www.modernpowersystems.com

The Power Group

64 SEPTEMBER 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

RESEARCH

of sediment is in there, and if there are any contaminants which

could affect how the sediment is handled or reused. Ultimately

this characterisation could determine whether reservoir dredging

goes ahead or not.

Sediment is generally characterised by particle size (sand, silt, or

clay) and through chemical analyses. Sediments composed largely

of sand are generally easy to dredge and de-water. Sediment com-

posed largely of silt is easy to dredge, but can be harder to de-

water, while sediment composed of clay is generally more difcult

to dredge and dewater. Knowing what type of sediment is in the

reservoir is important in determining a feasible approach to dredg-

ing, de-watering the sediment, and identifying potential sediment

re-use options.

HDR collected ve sediment core samples from different areas of

the reservoir, from the top 1.5-1.8m of sediment. This sampling depth

represents the extent to which handheld equipment can penetrate the

sediment layers. Furthermore, this depth also provides a reasonable

representation of sediment conditions throughout the reservoir. The

ve samples were then subjected to:

Contaminant analyses – this included a toxicity characteristic leach-

ing procedure for 40 contaminants to see if these could be washed

from the sediment into the water column. Tests were also carried out

for detection of the presence of metals such as arsenic, barium, lead

and mercury. If there are elevated levels of contaminants or metals,

the sediment will require special handling.

Physical analyses – this addressed particle size, bulk density and total

nutrients in order to determine the composition of the sediment.

Settleability testing – this determines how long it takes suspended

sediment to settle out of the water column.

HDR’s report concluded that there are no ndings in the results to

preclude or inhibit dredging the reservoir. It summarised that:

r The reservoir does not contain harmful levels of contaminants

or metals.

r The reservoir sediments are a mixture of layers with varying levels

of density, from fairly compact to relatively uid. Appropriate

dredging equipment capable of effectively removing the varying

densities of the sediment should be selected. These would include

spud-based, cutterhead type dredges that can impart sufcient exca-

vation force necessary to cut into the dense material. Similarly, if

mechanical dredging is utilised, then a barge mounted excavation

system capable of imparting sufcient force to cut into the denser

material would be required.

r The sediment in the Ivy Creek area and the middle and lower reach-

es of the main body of the reservoir are largely ne grained, and

require relatively extensive time to naturally settle once in suspen-

sion in the water column.

If dredging is conducted in the Ivy Creek area and the middle and

lower reaches of the main body of the reservoir using a hydraulic

suction dredge, use of a cationic polymer is recommended to increase

settling rates and effectiveness.

Land application of the dewatered sediment could provide bene-

cial soil qualities for agricultural applications.

Other areas that HDR Engineering focused on included an assess-

ment of the potential benets of reusing dredged material from the

reservoir. Its report stated that the availability of valuable dredged

material provides the opportunity for creative partnerships to meet

both environmental and economic objectives of the community.

If dredging moves forward the sediment would be suitable for

most types of applications. Once mechanically dewatered and

processed, the dredged material could be delivered at a favourable

cost compared to retail costs for local topsoil material and sand.

Depending on the market conditions at the time, some or all of

the cost difference could potentially be used to off-set the costs of

producing the dredged material. However, HDR did point out that

although sand is the most valuable component of the dredged sedi-

ments, it may require additional drying and processing at an off-site

stockpile site to be competitive with local retail sand.

ASSESSING FEASIBILITY

In June 2010, technical reports of the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir

Dredging Feasibility Study were released for public consultation.

The reports outlined the two-part dredging plan at a project cost of

between US$34-40M.

RWSA re-iterated that the scope of HDR Engineering’s services

was limited to the feasibility of dredging and did not include a review

of the CWSP – which backed expansion of Ragged Mountain.

Furthermore, the water authority believes that some citizens are inac-

curately advocating that the least cost method for securing future

water supplies is the dredging option. Recognising that this would

lead to cost comparisons between the two methods, RWSA has pre-

pared gures of cost analysis (see graphs).

By comparison, the reservoir expansion at Ragged Mountain

will provide 6.5B litres of additional useable storage compared

to 865M litres from the dredging plan. When the estimated costs

of the entire two-part dredging plan are compared to Schnabel

Engineering’s recent cost estimate for a new Ragged Mountain

reservoir, the new reservoir is signicantly less on a cost per unit

of storage added.

HDR’s study included an evaluation of benecial reuse and

identied a potential revenue source from sand recovery within

sediment at the upper end of the reservoir. While dredging this

upper end would only restore 223M litres of water storage (3%

of the volume added by a new reservoir at Ragged Mountain),

potential revenues could recover a substantial amount of the cost

for dredging this small section.

“There are at least two overarching questions that different citi-

zens are asking from this study, depending on their advocacy,”

Tom Frederick, executive director of RWSA said. “One question is

‘can dredging provide our future water supply needs cheaper?’ The

second is ‘does the current market provide an opportunity for a small

dredging project to benet the South Fork reservoir as a community

resource?’ We believe the answer to the rst question is no and the

second question is yes.”

The technical reports are now up for consultation. As IWP&DC

went to press a public meeting was taking place to consider the

proposals. RWSA is reafrming that the plan to build a larger res-

ervoir at Ragged Mountain should be sustained. However it also

recommends a more thorough assessment of proposals to dredge

the upper end of the South Fork reservoir, with sand recovery. It

needs to be determined if this is a cost-effective option and a way

forward.

To keep up-to-date with project progress log onto

RWSA’s website www.rivanna.org

IWP& DC

2000

1800

1600

1400

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

Useble storage added (Million gallons)

Volume of stored water added (MG)

Dredging Part I

Dredging Part II

Ragged Mountain

Reservoir

Graph showing volume of water storage added

ADVANCING

SUSTAINABLE

HYDROPOWER

14-17 June 2011 - Iguassu, Brazil

WORLD CONGRESS

water

sustainability

climate

investment

energy

WWW.HYDROPOWER.ORG

Main Congress Sponsors:

Media Partner:

Tel: +44 208 652 5290 | Fax: +44 208 643 5600 | Email: congress@hydropower.org | Web: www.hydropower.org

The IHA 2011 World Congress:

Don’t miss this opportunity to attend the hydropower

sector’s most challenging and enriching event of 2011!

Contact IHA today to register your interest in attending.

2010$08$06_IHA_Congress_Advert_1_Final.indd:::1 06/08/2010:::10:01:23

66 SEPTEMBER 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

RESEARCH

L

OOKING out to the sea on a stormy day it is impossi-

ble not to be impressed by the apparently vast amount

of energy in the waves and be overcome by the thought

that if only this energy could be harnessed it could make

a signicant contribution to the world’s energy supply. Of course,

inventors and engineers have been thinking just that for hundreds

of years, with the amount of effort in recent years increasing sig-

nicantly, initially as a response to the 1970s oil crisis and sub-

sequently in the 2000s due to climate change. As a consequence,

a large range of wave energy converters have been proposed and

continue to be developed in an attempt to harness this resource.

In the last few years this has progressed so that the rst prototype

wave energy converters, such as LIMPET, Pelamis and Oyster,

have been constructed and deployed. However, the industry

remains in its infancy.

In such a young industry there necessarily remain a large number

of areas where knowledge is limited; the wave energy resource is

one such area. Although it may seem obvious that a comprehensive

understanding and accurate measure of the wave energy resource is

required, effort has traditionally been focused on understanding the

fundamental hydrodynamics of wave energy converters and develop-

ment of novel device concepts.

The rst quantitative estimates of the wave energy resource were

made in 1974 by Professor Stephen Salter and Dr Dennis Mollison

using data collected by the Ocean Weather Ship ‘India’. This weather

ship was stationed in deep water, 700km off of the western coast

of Scotland. It was estimated that the annual average gross wave

energy density, dened as the total wave energy crossing into a circle

of one metre diameter in a year, to be approximately 800MWh;

although a subsequent analysis that removed systematic calibration

errors reduced this to approximately 700MWh/m. That is, if all this

wave energy could be converted into electricity, then there would

be enough wave energy crossing into a one metre diameter circle to

power approximately 100 homes. The Ocean Weather Ship ‘India’

was stationed at a particularly energetic site. However, many poten-

tial sites for wave farms have an annual average gross wave energy

resource of over 300MWh/m making wave energy a potentially sig-

nicant source of renewable energy.

By denition the gross wave energy resource includes all of the wave

energy. Thus, it includes all the wave energy during extreme events,

where survival is often a more pressing requirement than energy

production. It also includes wave energy incident from all directions

even though wave farm layout is likely to limit the amount of energy

available to individual devices from specic directions. However, the

average gross wave power density (simply the annual average wave

energy density divided by the number of hours in a year) continues to

be used as the standard measure of the wave energy resource. This is

exemplied by the publication of local and global maps of the wave

energy resource that continue to use this measure.

A consequence of using the average gross wave power density as

Is the nearshore a sensible place to put wave energy converters? Dr Matt Folley from

the Queen’s University of Belfast believes that it would be inappropriate to dismiss

nearshore technologies, based solely on information about the gross wave energy

resource. He explains how research into the exploitable wave energy resource will level

the playing eld for wave energy converters

Near or far?

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM SEPTEMBER 2010 67

RESEARCH

the measure of the wave energy resource is that the nearshore wave

energy resource appears much smaller than the offshore wave energy

resource. This is often cited as the reason that wave energy convert-

ers should be located offshore in deep water and possibly why the

vast majority of wave energy converters conceived are designed for

deep water.

The Marine Energy Research Group at Queen’s University Belfast

(QUB) has been involved in the research and development of wave

energy technologies since the 1970s. The group’s focus has princi-

pally been on shoreline and nearshore technologies. This includes

the development with Wavegen of the LIMPET shoreline oscillating

water column and more recently the development of Oyster with

Aquamarine Power. Although both technologies have been proven

to be technically successful it became clear that the historical deni-

tion of the wave energy resource was limiting the perceived poten-

tial of the technologies. Consequently, in 2008 the research group at

QUB endeavoured to dene a measure of the wave energy resource

more appropriate for the analysis of all wave energy converters. They

termed this measure the exploitable wave energy resource.

EXPLOITABLE WAVE ENERGY RESOURCE

The exploitable wave energy resource is designed to discount the con-

tributions from the highly energetic sea-states and to account for the

directional distribution of the wave climate. This would provide a

more appropriate measure of the wave energy resource. To achieve

this, the exploitable wave energy resource is calculated by constrain-

ing the gross wave power density in two ways.

The rst constraint is to only include the wave energy that crosses a

straight line orthogonal to the predominant direction of wave propa-

gation (this is sometimes called the net wave power density). Wave

energy takes many hundreds of kilometres of open water to develop

and any wave energy converter placed in the lee of another wave

energy converter will experience a reduced wave energy resource.

Thus, to maximise the power output of a wave farm, the wave energy

converters will logically be strung-out in a line orthogonal to the pre-

dominant direction of wave propagation. In this arrangement it is the

wave energy that crosses the line of the wave farm that is the resource

that can be effectively exploited.

The second constraint is that the maximum wave power density

that can be exploited is capped as a multiple of the average wave

power density. This constraint accounts for the maximum output

of the wave energy converter’s power take-off system and electri-

cal generator. For economic reasons this is typically equal to three

or four times the average power output, resulting in a load factor

similar to wind turbines. Technically, the appropriate limit to apply

to the wave power density depends on the relationship of the system

efciency with incident wave power and thus the particular technol-

ogy. However, a cap of four-times the average wave power density is

considered a reasonable approximation.

Having dened a more appropriate measure of the wave energy

resource, the Marine Energy Research Group at QUB investigated

the change in this resource as it approaches the shore. The investiga-

tions were performed using the third-generation spectral wave model

SWAN. SWAN models the propagation of the wave spectral energy

density in time and space. In addition, it also models the modication

of the wave spectral energy density due to wind growth, refraction,

shoaling, bottom friction, whitecapping and surf breaking, together

with changes to the spectral shape due to the internal hydrodynamics

of the waves. These models are the industry-standard for modelling

wave climates and sea-state transformations.

FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Initial investigations focused on idealised test cases so that the

effect of each loss mechanism could be isolated. These investi-

gations showed that in typical sea-states refraction is the princi-

pal cause of the reduction in the gross wave power density from

offshore to nearshore. In addition, in water with a depth of less

than two to three times the signicant wave height, surf breaking

also becomes a signicant loss mechanism. However, few wave

energy converters are proposed to be deployed in such shallow

water. Bottom friction, which is often quoted as being the main

loss mechanism, was found to typically account for less than a

10% reduction in wave power density.

Further investigations used wave hindcast data 20km off of the

coast of West Orkney, Scotland. At this site the bathymetry was

approximated as a 1:100 slope. These investigations showed that

to the 10m depth contour the annual average gross wave energy

resource decreased by 30%, whilst the annual average exploitable

wave energy resource decreased by only 13%. A similar study off of

the coast of South Uist, Scotland, where there is a 1:400 seabed slope,

showed a decrease of 44% in the annual average gross wave energy

resource, but only a 23% decrease in the annual average exploitable

wave energy resource.

Finally, investigations were also performed using nine years of

wind/wave hindcast and bathymetry data for the Wave Energy

Converter Test Site at the European Marine Energy Centre located in

the Orkney Islands, Scotland. This analysis showed that there is less

than a 10% difference between the exploitable wave energy resource

at the ‘deep water’ test berth (located in 50m water depth) and the

nearshore test berth (located in 10m water depth).

All these investigations show that the difference between the gross

and exploitable wave energy resources is smaller nearshore than it

is offshore. The seabed to the nearshore can be considered as acting

as a lter that keeps only the exploitable waves. That is, the seabed

refracts the incident waves so that they come from a more concen-

trated direction and also causes the largest waves to break limiting

their power density and destructiveness. Viewed from this perspective

the nearshore appears much more inviting.

INAPPROPRIATE PERCEPTIONS

The conclusion from these investigations is that whilst the wave

energy resource is smaller nearshore compared to offshore, the dif-

ference is much less signicant than use of the gross wave energy

resource suggests. The difference is sufciently small to suggest that

nearshore wave energy converters cannot be dismissed based solely

on the available resource; other factors that determine the cost of

energy become relatively more signicant.

The different environments in the nearshore and offshore means

that in general the technologies developed are distinct. For example,

Pelamis requires a minimum of about 50m water depth for deploy-

ment because the moorings must have sufcient compliance to mini-

mise loads during storms; it could not be deployed in the nearshore.

Indeed, nearshore wave energy converters can be cheaper or have a

better performance than their offshore counterparts. For example,

wave energy converters that react against the seabed are generally

cheaper in shallower water due to a reduction in load-path lengths. In

addition, wave energy converters that exploit the surge motion of the

waves generally have a better performance in the nearshore as depth-

induced shoaling increases the waves’ surge amplitudes. Electrical

cable lengths and other shore connectors will also be shorter when

the wave energy converters are closer to the shoreline reducing both

costs and failure rates.

The economics of wave energy converters remains to be proven.

However, the investigations have shown that it would be inappropri-

ate to dismiss nearshore technologies based solely on information

about the gross wave energy resource. A new, more suitable, measure

for comparing sites for wave energy converters has been identied and

this has been termed the exploitable wave energy resource. This has

levelled the “playing eld” so that the most promising technologies

are developed without being hampered by inappropriate perceptions

of the wave energy resource.

Dr Matt Folley, Senior Research Fellow, Marine Energy

Research Group, School of Planning, Architecture and Civil

Engineering, Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland

Email: m.folley@qub.ac.uk

IWP& DC

68 SEPTEMBER 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

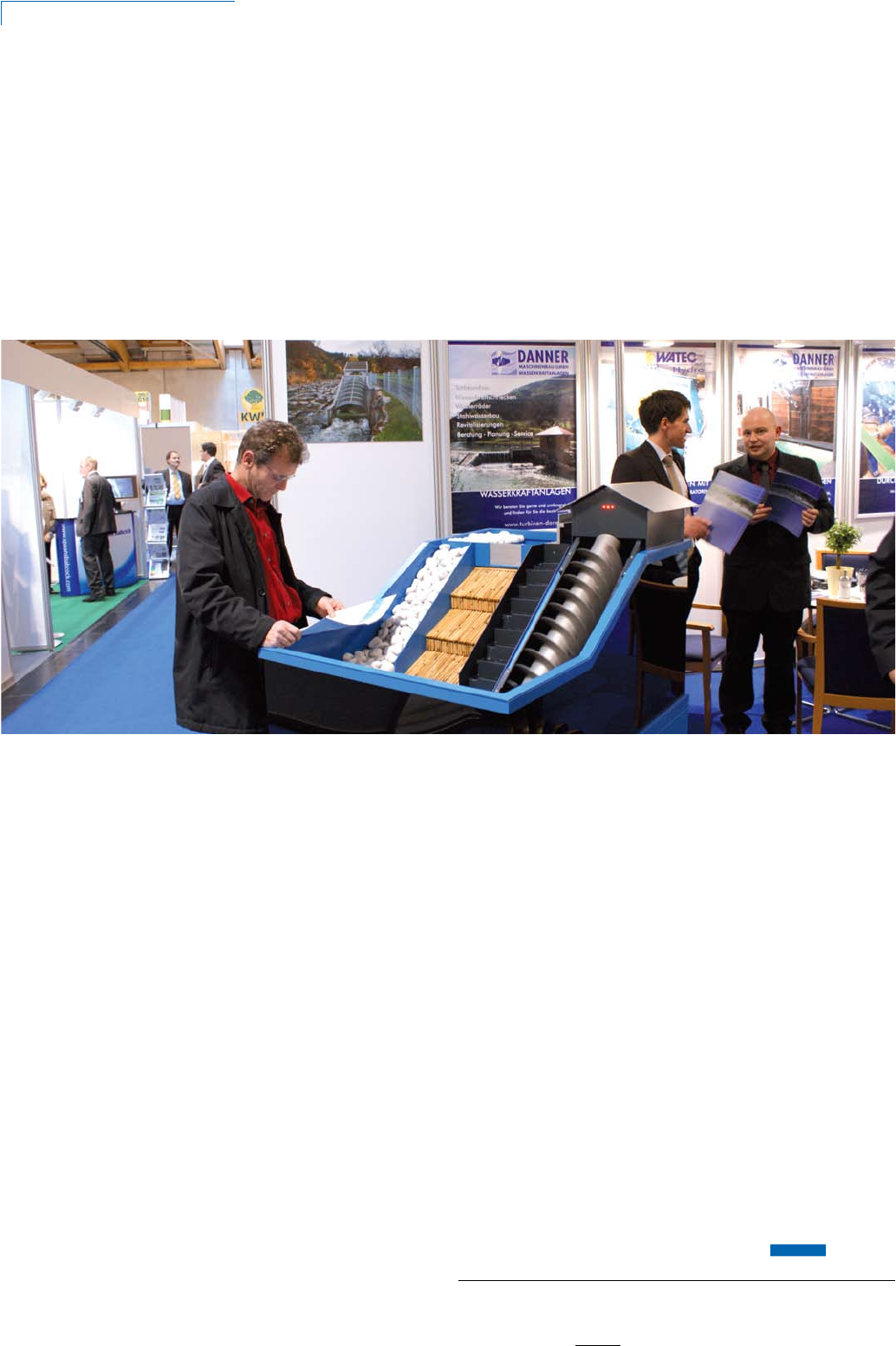

CONFERENCE PREVIEW

F

ROM 25-27 2010, the Trade Fair Center Salzburg will be

lled with hydropower companies covering the complete

range of the supply chain. After a successful premiere last

year, the “Hydro Power Street” will return and offer an

excellent forum for exchanging information and presenting the

potential applications of hydropower.

Companies such as Ritz-Atro GmbH, Spaans Babcock bv, Danner

Maschinenbau GmbH, Hamann Turbinen GmbH & Co. KG Austria,

Elektro Bischofer Ges.m.b.H. + Co. KG, Duktus Tiroler Rohrsysteme

GmbH, Lukas Anlagenbau GmbH, Walter Schuhmann Mühlen- und

Maschinenbau GmbH, Herkules Aquatec GmbH as well as Forbo

Siegling Austria GmbH, to name a few, will be presenting themselves

at the international trade fair and conference, with European hydro

associations present with a special a collaborative exhibition stand.

This year’s trade fair will also feature the new “International

Brokerage Event” which will allow business contacts and new syner-

gies to be created in a fast and effective way. As at last year’s trade

fair, the exhibitors’ forum will again feature free and informative

presentations from exhibitors only.

The premiere of last year’s small hydropower conference was suc-

cessful with all 100 available spots booked in advance. At this year’s

event, REECO Austria GmbH and the European Small Hydropower

Association (ESHA) are presenting the 2nd International Small

Hydropower Conference for 200 participants.

Papers to be presented at the event include:

r River hydropower projects along Salzach River by Prof. Dr. Markus

Aueger, University of Innsbruck

r Planning and implementation of a different kind of small hydro-

power facility on the upper River Danube by Dr. Stephan Heimerl,

Fichtner GmbH & Co. KG

r Optimization of water inow at hydropower plants by Prof. Dr.

Gerald Zenz, Technical University of Graz

r Reduction of sediment deposits in the tailwater of hydropower

plants by Dr. Josef Schneider, Technical University o Graz

r Post graduate course in sustainable hydropower - 1st phase by

Martin Scharsching, EVH AG

r The Austrian National Water Development Plan (NGP) and the

new regulation concerning Ecological Quality Goals by Dr. Charlie

Panek, ARGE Ökologie OG

r Hydrokinetic turbines without banked-up water level by Dr. Albert

Ruprecht, University of Stuttgart IEH

r Screw turbines under examination by Alois Lashofer, Irina Kampl,

University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Vienna

r The hydropower potential of existing lateral barriers in Austria by

Werner Hawle, University of Natural Resources and Applied Life

Sciences, Vienna

r Use of multidimensional discharge and sediment transport models

in planning hydropower facilities by Dr. Peter Mayr, MAYR &

SATTLER OEG

r Revitalization of the weir at hydropower plant Kleinmünchen

– Traunwehr by Alfred Mayr, Braun Maschinenfabrik GmbH

& Co. KG

In addition on the rst day of the event (25 November 2010), after

the ofcial opening ceremony, hydropower in Austria will be put

in the spotlight. Companies such as Forbo Siegling Austria GmbH

and KLAWA Anlagenbau GmbH, will present their products and

projects.

Network partners for the event include Kleinwasserkraft Österreich,

Bundesverband Deutscher Wasserkraftwerke e.V., Landesverband

Bayerischer Wasserkraftwerke eG, Interessenverband Schweizerischer

Kleinkraftwerks Besitzer, Schweizerischer Wasserwirtschaftsverband

and the International Centre for Hydropower.

Further information on the trade fair, the conferences and

the accompanying programme is available on:

www.renexpo-austria.com.

IWP&DC provides a preview to the RENEXPO Austria trade fair,

to be held 25-27 November in Salzburg, Austria

Fair game in Austria

The exhibition hall at the 2009 event

IWP& DC

7:70U]LZTLU[Z3[KOLYLI`PU]P[LZPU[LYLZ[LKWHY[PLZ[VYLZWVUK

[V[OPZ9LX\LZ[MVY0UMVYTH[PVU¸9-0¹YLNHYKPUNHWYVWVZLKM\

[\YL[LUKLY[VI\PSK[^V7\TWLK:[VYHNL7V^LY7SHU[Z;OPZ9-0

ZLLRZ[VPKLU[PM`X\HSPÄLKJVU[YHJ[VYZZWLJPHSPaPUNPUJVUZ[Y\J[PVU

VM\UKLYNYV\UK7\TWLK :[VYHNL7V^LY 7SHU[Z HUK JVSSLJ[ [OL

PUK\Z[Y`»ZWLYZWLJ[P]LHUKMLLKIHJRVU[OL7YVQLJ[;OLPU[LUKLK

JVUZ[Y\J[PVUZJVWLVM^VYR^PSSPUJS\KL;\UULSPUN=LY[PJHS:OHM[

,_JH]H[PVU VM 7V^LY /V\ZL *H]LYU *VUJYL[L Z[Y\J[\YLZ HUK

,SLJ[YV4LJOHUPJHSLX\PWTLU[PUZ[HSSH[PVU

*VU[YHJ[VYZ PU[LYLZ[LK PU YLWS`PUN ^PSS IL YLX\LZ[LK [V ÄSS 9-0

KVJ\TLU[Z7SLHZLJVU[HJ[4Y9VULS3H\YLU[PUVYKLY[VYLJLP]L

[OL9-0+VJ\TLU[Z!YVULS'HK`YJVPS

+LHKSPULMVYZ\ITPZZPVU¶+LJLTILY

9-0

76)V_6TLY0UK\Z[YPHS7HYR

)\PSKPUN¶6TLY0ZYHLS

;LS -H_

;OL*VUZ[Y\J[PVUVM;^V7\TWLK:[VYHNL7SHU[Z

H[.PSIVHHUK4HUHYH

4>4>YLZWLJ[P]LS`0ZYHLS

psp.indd 1 9/9/10 15:14:08

PROFESSIONAL DIRECTORY

70 SEPTEMBER 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

CLASSIFIED

www.waterpowermagazine.com

MORE THAN 100 YEARS OF HYDROPOWER ENGINEERING

AND CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT EXPERIENCE

260 Dams and 60 Hydropower Plants (15,000 MW)

built in 70 countries

Water resources and hydroelectric development

•Public and private developers

•BOT and EPC projects

•New projects, upgrading and rehabilitation

•Sustainable development

with water transfer, hydropower, pumping stations

and dams.

COYNE ET BELLIER

9, allée des Barbanniers

92632 GENNEVILLIERS CEDEX - FRANCE

Tel : +33 1 41 85 0 3 69

Fax: +33 1 41 85 03 74

e.mail: commercial@coyne-et-bellier.fr

website: www.coyne-et-bellier.fr

COYNE ET BELLIER

Bureau d’Ingénieurs Conseils

www.coyne-et-bellier.fr

Over 40 years experience in Dams.

CFRD Specialist Design and Construction

●

Dam Safety Inspection

●

Construction Supervision

●

Instrumentation

●

RCC Dam Inspection

●

Panel Expert Works

Av. Giovanni Gronchi, 5445 sala 172,

Sao Paulo – Brazil

ZIP Code – 05724-003

Phone: +55-11-3744.8951

Fax: +55-11-3743.4256

Email: bayardo.materon@terra.com.br

ba_mater@yahoo.com.br

Lahmeyer International GmbH

Friedberger Strasse 173 · D-61118 Bad Vilbel, Germany

Tel.: +49 (6101) 55-1164 · Fax: +49 (6101) 55-1715

E-Mail: bernd.metzger@lahmeyer.de · http://www.lahmeyer.de

Your Partner for

Water Resources and

Hydroelectric Development

All Services for Complete Solutions

• from concept to completion and operation

• from projects to complex systems

• from local to multinational schemes

• for public and private developers

• hydropower

transmission and high

voltage systems

power economics

power management

consulting

www.norconsult.com

Multidisciplinary consultancy

services through all project cycles

dams and waterways

turbines/pumps and

generators

water resources

environmental and

social safeguards

AF-Colenco Ltd

Täfernstrasse 26 • CH-5405 Baden/Switzerland

Phone +41 (0)56 483 12 12 • Fax +41 (0)56 483 17 99

colenco-info@afconsult.com • http://www.af-colenco.com

Consulting / Engineering and EPC Services for:

• Hydropower Plants

• Dams and Reservoirs

• Hydraulic Structures

• Hydraulic Steel Structures

• Geotechnics and Foundations

• Electrical / Mechanical Equipment

Construction and

refurbishment of small

and medium hydro

power plants.

.

t

u

r

n

k

e

y

/

E

P

C p

l

a

n

t

s

.

d

e

s

i

g

n

&

e

n

g

i

n

e

e

r

i

n

g

.

t

u

r

b

i

n

e

s

.

f

eas

i

bi

l

i

ty

s

t

udi

e

s

.

o

p

e

r

a

t

i

o

n

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

.

financ

i

ng

www.hydropol.cz

# (47) 67 53 15 06 in Norway

# (55) 11 3722 0889 in Brazil

E-mail: nickrbarton@hotmail.com

Website: http//www.qtbm.com

3

3

5

5

y

y

e

e

a

a

r

r

s

s

e

e

x

x

p

p

e

e

r

r

i

i

e

e

n

n

c

c

e

e

f

f

r

r

o

o

m

m

m

m

o

o

r

r

e

e

t

t

h

h

a

a

n

n

3

3

0

0

c

c

o

o

u

u

n

n

t

t

r

r

i

i

e

e

s

s