Water and Wastewater Engineering

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

16-8 WATER AND WASTEWATER ENGINEERING

These factors are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Contaminant Removal. Rem oval of contaminants is the primary purpose of most treatment

processes . In the United States, the regulations promulgated by the U.S. Environmental Protec-

tion Agency set the maximum allowable contaminant levels (MCLs). Obviously, processes that

cannot achieve the MCL for a single contaminant or group of contaminants can be quickly elim-

inated. For example, if arsenic is the sole contaminant constituent of concern, a quick review

of Table 16-1 reveals that MF and UF mem branes are not an option that should be cons idered.

However, Table 16-1 is not the be all, end all in the sc

reening process. While the table shows

seven other options that should be considered, the tables and decision trees in Chapter 14 pro-

vide a much more refined list of options and guidance in making choices for arsenic removal.

Many utilities choose to produce water that is much better in quality than that required

to

comply with the regulations. This includes improving the aesthetic characteristics of the water.

Many of the processes that are needed to provide the water qu ality required to meet the regula-

tions may be operated in a manner that yields a higher quality than is required by the regulations.

One way to get higher quality is

to operate at lower loading rates than the customary norms. An-

other way is to provide additional treatment processes.

Source Water Quality. In the simplest view, a comparison of the sourc e water quality and

the desired finished water quality set the required degree of treatment. The variation in the

source water quality must be within the range of quality that the treat

ment plant can success-

fully treat.

Process or

contaminant

Table or

figure number Remarks

Arsenic Tables 14-1, 14-2, 14-3

Figures 14-1 & 14-2 Decision tree & graph

Disinfection Tables 13-4, 13-5, 13-6,

13-7, 13-9, 13-10

Figures 13-9, 13-10 Decision trees

GAC Table 14-10

Iron & Manganese Figures 14-5 & 14-6 Decision trees

NF/RO membranes Table 9-1

MF

/UF membranes Table 12-1

Radium Table 14-7

Residuals

ArsenicFigures 15-13 & 15-14 Decision trees

Liquid Table 15-10

Figures 15-11 & 15-12 Decision trees

Radioactive Figures 15-15 & 15-16 Decision trees

Sludges Table 15-4 Lime & coagulation

TABLE 16-4

Summary of tables and figures to aid in screening alternatives

DRINKING WATER PLANT PROCESS SELECTION AND INTEGRATION 16-9

In some cases, the characteristics of the raw water suggest the need for a particular treatment

process. An example is the use of dissolved air flotation (DAF) in treating algae laden water or

greensand to treat groundwater with high concentrations of iron.

Often a c ommunity will use multiple sources for their water s upply. While this make

s the

decision process even more complex, it offers opportunities for blending to dampen fluctuations

in raw water quality as well as improving reliability of the source.

Reliability. As used here, the term reliabi lity includes robustness as well as mean time be-

tween failures

. Robustness includes the ability to handle changes in raw water quality, on-off

cyclic operations, normal climatic changes, adverse weather events, and the degree of mainte-

nance required to maintain efficient operation. Althou gh minimum redu ndancy requirements

(e.g., Table 1-3) help to ensure reliability, they do not take into acco

unt failures becau se the

equipm ent is operated outside of its normal operating range or failure to meet water quality

goals becaus e of frequent or very long down time for repairs.

Existing Conditions. Upgrades and expansion of existing facilities requires careful evaluation

of the existing process and the constraint

s of the site. Hydraulic requirements may often limit the

choices in process selection and design configuration.

Process Flexibility. The ability of the operator to mix and m atch various processes to adapt

to variations in demand ranging from minimum demand at initial start-up of the plant to m

ax-

imum demand at the design life is essential to providing consistently good quality water. In

addition, the ability to “work around” scheduled out-of-service maintenance requirements as well

as unscheduled maintenance for repair of failures should be planned

in the selection of process

options. Both the plant layout and the hydraulics of the plant play a role in providing this flex-

ibility. These are discussed later in this chapter.

A more difficult requirement is the flexibility to meet changing regulatory requirements (which,

generally, will become more stringent rather than less stringent) or change

s in the source water

characteristics. For a given set of site characteristics, planning for future expansion is one logical

way to provide flexibility. In some cases it may be possible to provide extra space in the hardened

facilities (i.e., concrete structures) to allow for addition of equ

ipment when the need arises. Provid-

ing access doors or roof structures to the space is also a good idea. There is, of course, the risk that

the space will never be needed.

Utility Capabilities. The water utility must be able to operate the plant once it is built. This

includes repairs as well as day-to-day ad

justments, ordering supplies , taking samples, and so

on. Processes should be selected that can be operated and maintained by available personnel or

personnel that can be trained. The plant management must be informed of the complexities and

requirements of the treatment process before plans

are adopted. Staff training, as well as avail-

ability and access to service, are important considerations in selecting a process.

For many small (501 to 3,300 people) and very small (25 to 500 people) communities and

even some medium (3,301 to 10,000) to very large (100,000 people) communities, there are

economies of sc ale in joining with others to provide treated water. The economies of scale are

found primarily in capital cost, outside services, and materials. Energy and, to a lesser extent,

16-10 WATER AND WASTEWATER ENGINEERING

labor costs do not exhibit as significant an economy of scale (Shih et al., 2006). Based on survey

data, Shih et al. found that the median unit production cost (operating cost plus depreciation in

$/m

3

of water delivered) for a very small plant was 135 percent greater than that for a very large

plant. On the other hand, 20.7 percent of very small plants and 22.0 percent of medium-sized

plants had a unit cost lower than the median unit cost of very large plants. Thus, larger size does

not guarantee lower costs. In addition to the political issues of local control, a caref

ul economic

evaluation of the alternative of joining with another community is warranted.

Costs. The capital cost may be the key factor in selection of a process. As noted in Chapter 1,

the operating cost is, in all likelihood, equally relevant. It may be even more important than capi-

tal cost in the decision process because of the rising cost of energy an

d labor.

Environmental Compatibility. The issues included under this heading range from residuals

disposal to the wastage of water in the treatment process. Advanced processes that generate re-

sidu als with high concentrations of materials that are d ifficult to dispose of may be sufficient

reason to reject the

m. Likewise, processes that reject large quantities of water with respect to the

quantity of water produced should be reviewed carefully. This is especially true in areas where

water supplies are limited.

Process Selection Examples

The following three case studies were selected from the literature to demonstrate the wide range

of choices and some of the logic that was used in making the choices. The cited references pro-

vide more detail. A literature review of the many other examples that are reported in the Journal

American Water Works Association and Opflow

(also published by the American Water Works

Association) should be part of any study to evaluate process alternatives.

Case Study 16-1

Groundwater sources that are hydraulically connected to a surface water source mus t comply

with EPA’s rules under the category called “groundwater under the influence of surface water,”

more frequently cited as “groundwater

under the influence.” Although this designation imposes

requirements for water quality that are not normally applied to groundwater, the use of wells “un-

der the influence” may have significant advantages over direct withdrawal from surface water.

This source of water is often referred to as river bank filtrat

ion or just bank filtration.

The effec tiveness of bank filtration has long been recognized in Europe. Many utilities are

interested in bank filtration in the United States because it has the potential to remove pathogenic

microorganisms and reduce disinfection byproduct precursors.

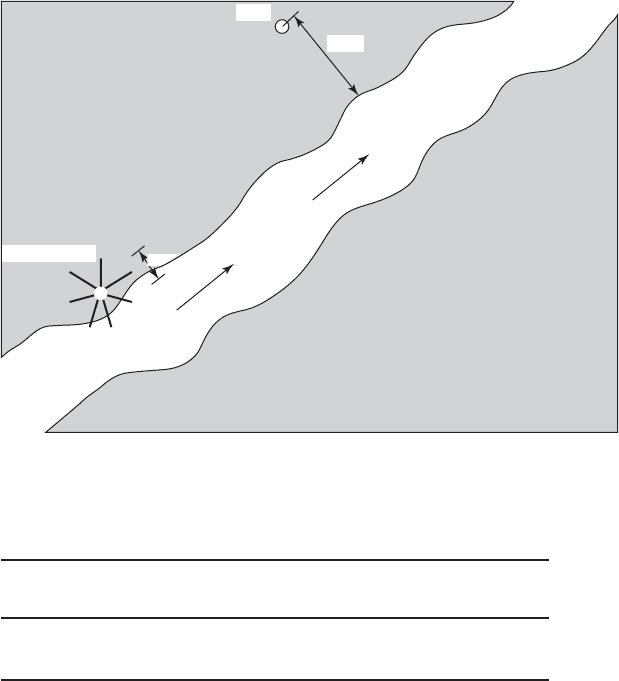

Discussion. The paper by Weiss et al. (2003) was selected to illustrate a c o

mparison of three

sources for a water supply: a river, a horizontal collector well, and a vertical well located 122 m

from the river.

The river is the Wabash River at Terre Haute, Indiana. The site is sketched in Figure 16-2 .

The characteristics of the collector well and the individual well are as shown in Table 16-5 .

DRINKING WATER PLANT PROCESS SELECTION AND INTEGRATION 16-11

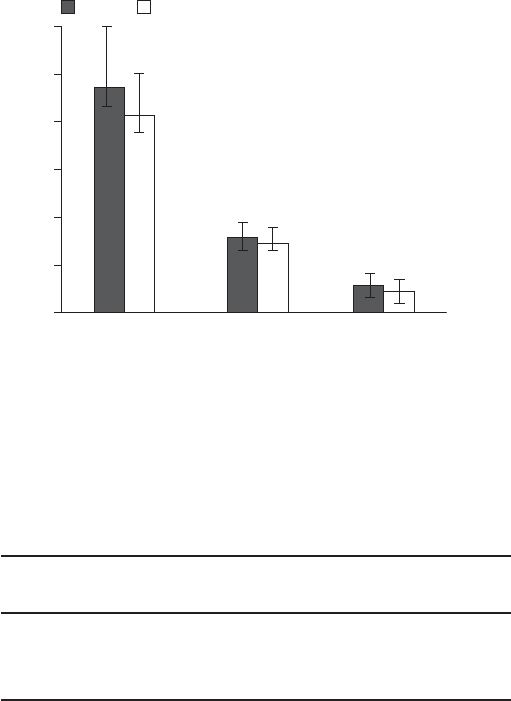

The average total organic carbon (TOC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) for each source

are shown in Figure 16-3 .

T h e Clostridium and E. coli C bacteriophage concentrations for each source are given in

Table 16-6 .

Both the collector well and the vertical well achieved a remarkable improvement in the

source water quality over direct withdrawal fro

m the river.

Comments:

1 . Not investigated in the paper by Weiss et al. were several other potential effects of bank

filtration (Tufenkji, Ryan, and Elimelech, 2002):

a . When there is intense microbial activity in the river bed sediments, the oxygen is de-

pleted and anoxic conditions result.

b . Microbial activity under anoxic conditions

results in reduction of the nitrate

concentration.

Collector well

Well

122 m

Wa

s

bas

h River

27 m

FIGURE 16-2

W a b a sh River at Terre Haute, Indiana.

Well ID

Depth to

well screen, m

Well screen

length, m

Well capacity,

m

3

/d

Collector 24

480

a

45,500

Well No. 3 45 14 3,760

TABLE 16-5

Characteristics of the wells at Terre Haute, Indiana

a

Ranney screen.

16-12 WATER AND WASTEWATER ENGINEERING

c . If the aquifer becomes highly reduced, manganese and iron are mobilized, which may

result in a deterioration of the water quality. If the well system is at the outer limit of the

surface water–groundwater interface, oxidation results in precipitation of these metals.

d . Microbial degradation of organic matter mobilizes metal

s such as copper and cadmium.

e. Excessive microbial growth may decrease hydraulic conductivity at the surface water–

groundwater interface as a result of biofilm formation.

2. The effects of grou ndwater dilution as well as the subsurface filtration as

pects of river

bank filtration are assessed in a paper by Partinoudi and Collins (2007).

Case Study 16-2

The Milwaukee Cryptosporidium o utbreak in 1993 had a major impact on process selection for

both new construction and upgrades. This coupled with U.S. EPA’s increasingly stricter drinking

water regulations is influencing utilities to consider low-pressure membrane (MF and UF) as

part

of their multibarrier treatment train.

Wabash River

6.0

5.0

4.0

3.0

2.0

1.0

0.0

Collector well

Well 3

TOC DOC

TOC or DOC—mg/L averaged over sampling dates

DOC—dissolved organic carbon, TOC—total organic carbon

Number of sampling events 16 for DOC, 19 for TOC

FIGURE 16-3

Average TOC and DOC concentrations at Terre Haute, Indiana.

( Source: Weis et al., 2003.)

Location

Clostridium

average counts/100 mL

E. coli C

pfu/100 mL

Wabash River 183 147

Collector well 0.07 0.07

Well 3 0.07 0.07

TABLE 16-6

Clostridium and E. Coli concentrations at Terre Haute, Indiana

DRINKING WATER PLANT PROCESS SELECTION AND INTEGRATION 16-13

Discussion. Shorney-Darby et al. (2007) present a detailed explanation of the evaluation of MF

membranes for expansion of the Modesto Regional Water Treatment Plant (MRWTP) in central

California. The existing 136,000 m

3

/ d plant was a conventional system that employed ozone dis-

infection, alum coagulation, flocculation, sedimentation , and deep-bed monomedium filtration to

treat water from the Modesto Reservoir. The plant was commissioned in 1995 and has operated

well. The original design incorporated features for expansion to 273

,000 m

3

/ d using the same pro-

cesses of conventional treatment. Table 16-7 summarizes the raw water and filter effluent quality.

In the summer months, when there are few rain events in central California, turbidity and TOC

concentrations are stable and low in the raw water supply (5 NTU and 1.3 mg/L, respectively).

During the rainy winter months, the turbidity can rea

ch 20 NTU and TOC concentrations can

double.

The screening process for the expansion project was limited to two choices: replication of the

existing plant and construction of a parallel MF plant. Because the conventional plant was well

known, the study focused on the implications of a new MF plant. The particular concern was the

higher turbidity and TOC in the winter.

A pilot study was cond

ucted to see if pretreatment (e.g., coagulation, flocculation, and set-

tling) would be required to achieve satisfactory operation. The main conclusions from the pilot

testing were the following:

• Low-pressure mem branes can effectively treat Modesto Reservoir water at a reasonable

water flux with reasonable cleaning intervals;

• No pretreatment upstream of the membranes

is necessary; and

• The membrane train can operate for several months each year without coagulant but low dos-

ages of alum ( 8mg/L) may have to be used to lower TOC concentrations in the rainy season.

The 20-year present worth cost estimates for the conventional plant and the MF plant dif-

fered by less

than 10 percent. This fact, coupled with favorable pilot testing led to the decision to

proceed with the MF option. This decision was facilitated by the recognition that the MF plant

would allow for future expans ion while the construction of a parallel conventional plant would

use all of the available land.

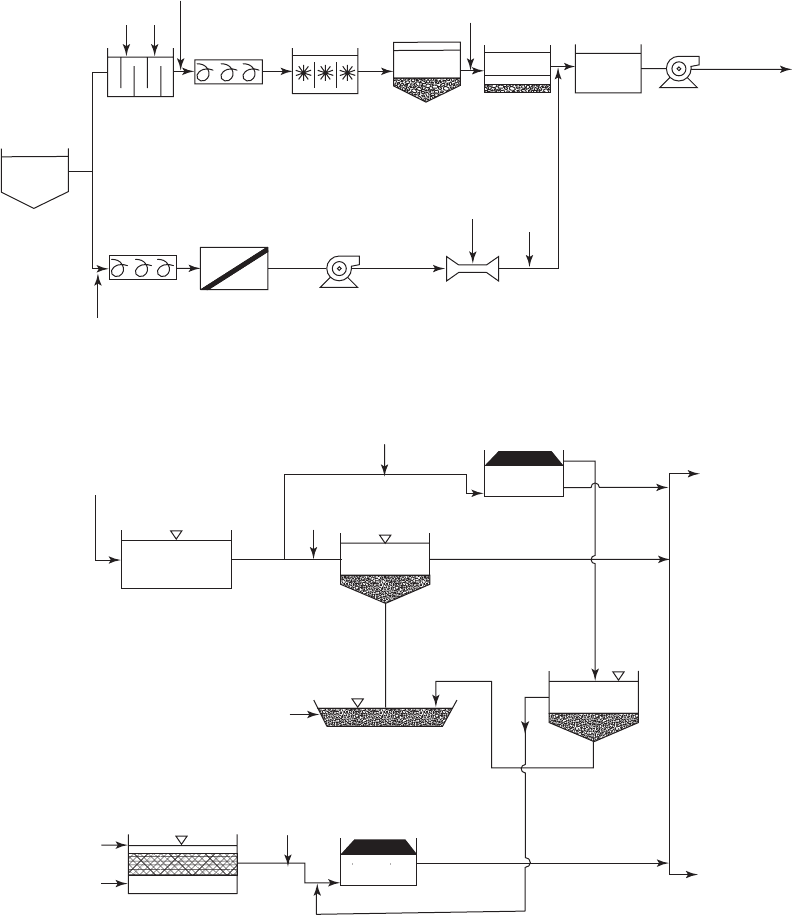

The final treatment train arrangement is shown in Figure 16-4 .

Parameter Raw water Filter effluent

Turbidity, NTU 1.5 to 19.4 0.015 to 0.130

Total organic carbon mg/L 1.1 to 3.4 0.78 to 2.2

Total coliform, MPN/100 mL 0 to 1,733 0

Fecal coliform, MPN/100 mL 0 to 300 0

Cryptosporidium, counts/100 mL

0 to 0.05 N/A

Giardia, counts/100 mL

0 to 0.02 N/A

Algae, cells/ mL625 to 38,750 N/A

pH 5.9 to 7.4 8.1 to 9.0 (finished

water)

Temperature, C4.5 to 21

TABLE 16-7

Range of MRWTP water quality data: January to April, 2007

A dapted from Shorney-Darby et al., 2007.

16-14 WATER AND WASTEWATER ENGINEERING

Alum

NaOH

Static

mixer

Ozone

contactor

Flocculation

basins

Sedlmentation

basins

Stabilization

basins

Filters

(deep bed

monomedium)

Pump

O

3

CaS

2

O

3

CaS

2

O

3

NaOCL

Modes to

Reservoir

NaOCL

Flume

contactor

Pump

Membranes

Static

mixer

Alum

FIGURE 16-4

Parallel conventional (top) and membrane (bottom) treatment trains for expanded Modesto Regional Water Treatment Plant.

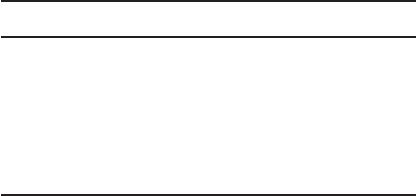

FIGURE 16-5

R e siduals treatment trains for expanded Modesto Regional Water Treatment Plant.

Underflow

Underflow

Underflow

Recycle to

membrane

train

Sludge

wet well

Sludge lagoon

Sedimentation

basin sludge

Alum &

polymer

DAF

Recycle to

conventional

train

DAF

Alum &

polymer

Alum &

polymer

Solids

thickener

Conventional

filter

backwash

Washwater

recovery

basin

Membrane

backwa

sh

Neutralized and

treated CIP waste

Membrane

backwash

equalization

basin

Residuals handling in the new plant configuration required carefu l planning. Because the

polymers used in thickening the conventional treatment residuals potentially could damage the

membrane via the recycled decant water, separate handling systems were used ( Figure 16-5 ). In

DRINKING WATER PLANT PROCESS SELECTION AND INTEGRATION 16-15

addition, recycling of MF clean-in-place (CIP) chemicals was found to disrupt the coagulation

and sedimentation processes. Some of the CIP chemicals will be neutralized and returned to the

head end of the plant. Others will be hauled off-site for disposal.

Comment. A major disadvantage of us

ing the MF for the expansion is that, in effect, there

are two plants to operate: a conventional plant and a MF plant. This implies that operators with

exceptionally diverse skills must be employed or two, almost independent staffs have to be pro-

vided. In addition, with the exception of alum, two different sets of chemicals must be stored and

maintaine

d.

Case Study 16-3

A s noted in Chapter 2, groundwater has many characteristics that make it preferable as water sup-

ply. But it is not without drawbacks, including high concentrations of manganese, iron, hydrogen

sulfide, or ammonia.

Discussion. Sled and Pierson (2007) describe the treatment objectives and processes sele

cted

for the upgrade of the Renton, Washington water treatment plant. The raw water quality charac-

teristics are described in Table 16-8 .

The treatment objectives for the new treatment plant were:

• Eliminate customer complaints about manganese staining of clothes and fixtures.

• Produce treated water with a free chlorine residual.

• Improve the taste and o

dor of the water.

• Eliminate hydrogen sulfide odor in the ambient air that occurred with the previous air strip-

ping process.

• Increase the dissolved oxygen to match that of the city’s other water supplies.

• Meet the pH requirements for continued compliance with the Lead and Copper Rule.

The treatment objectives were quantified by

selecting the water quality objectives shown in

Table 16-9 .

The major components of the new treatment process are granular activated carbon (GAC)

for hydrogen sulfide removal, greensand for manganese and iron removal, and breakpoint

Parameter Range of values

Ammonia, free, mg/L 0.35 to 0.55

TOC, mg/L 0.46 to 1.9

Total iron, mg/L 0.0 to 0.04

Total manganese, mg/L 0.07 to 0.12

Sulfide, mg/L 0.06 to 0.20

pH 7.6 to 8.0

TABLE 16-8

Renton, Washington raw water quality characteristics

Adapted from Sled and Pierson, 2007.

16-16 WATER AND WASTEWATER ENGINEERING

chlorination for ammonia reduction. Three 3.6 m diameter GAC columns and three 3.6 m

diameter greensand filters are used in the plant. This provides a capacity of 16,000 m

3

/ d. Space

is provided to add two more GAC columns and two more greensand filters to bring the capacity

to 30,000 m

3

/ d. Sodium hypochlorite is used for breakpoint chlorination. Contact is provided in

an underground clearwell that is provided with serpentine baffle walls.

Comments:

1 . The translation of the treatment objectives into quantitative measures is an excellent way

to assess the capability of alternative processes.

2. The provision of “hardened” s

pace for expansion gives Renton flexibility for the future.

3. The paper presents many worthwhile lessons learned for consideration in start-up of a new

facility of this type as well as suggestions for training programs with new equipment.

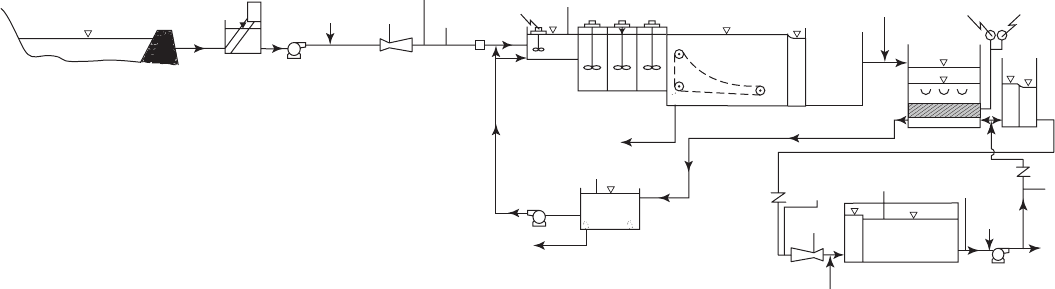

16-3 PROCESS INTEGRATION

Plant Layout

The available land area and topography dictate the plant layout. The conceptual framework for

the plant layout begins with the process flow diagram ( Figure 16-6 ). The process flow diagram

should include the following items (Kawamura, 2000):

1 . All the unit processes in the correct sequence.

2. All the major pipe connections with flow directions.

3. All the chemicals that are to be used and the application points of each.

4. All the major sampling points.

5. The location and size of all major flow meters, valves, and connecting pipes.

6. The location of all major pumps, blowers, and screens.

7. The control points for pressure, water level, flow rate, and water quality.

The basic

s tyles of plant layout are the linear style, compact style, and campus style

( Figure 16-7 ). In general, the linear and campus styles have several advantages over the compact

Parameter Treatment objective

Ammonia, free, mg/L 0.025

Total iron, mg/L 0.05

Total manganese, mg/L 0.01

Sulfide, mg/L 0.0003

pH 7.6 to 8.0

TABLE 16-9

Renton, Washington treated water quality objectives

A dapted from Sled and Pierson, 2007.

16-17

GAC

Filter

control

structure

Filters

Influent

screening

Influent

pumping

KMnO

4

,

PAC

Flow

monitoring

pH

monitoring

Turbidity

monitoring

Flash

mixer

Lime, alum or

iron salt

KMnO

4

, PAC Cl

2

Flash mix

chamber

Flocculation basins

Sedimentation basins

To disposal

Sludge

To disposal

Recycle

pump

Level

monitoring

Cl

2

HWL

LWL

Level

monitoring

Turbiditty, chlorine

(or other

disinfectant)

residual and pH

monitoring

Chlorine (or other

disinfectant)

residual and pH

monitoring

Cl

2

corrosion

inhibitter

To city

distribution

High lift

pumps

Turbidity

monitoring

Headloss

monitoring

Supplemental

backwash wate

r

Flowmeter

Chlorine contact

and clearwall

Flow

monitoring

Effluent

flow meter

Cl

2

, NaOH,

corrosion inhibitor

floride

Reservoir

Sludge

Waste

washwater

holding basin

FIGURE 16-6

E xample of a process flow diagram.