Van Huyssteen J.W. (editor) Encyclopedia of Science and Religion

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

TIME:RELIGIOUS AND PHILOSOPHICAL ASPECTS

— 897—

of a “supposition or imagination of time” (Sorabji,

p. 237). In the same vein, Aquinas stated:

God is before the world by duration. The

term ‘duration’ here means the priority of

eternity, not of time. Or you might say that

it betokens an imaginary time, not time as

really existing, rather as when we speak of

nothing being beyond the heavens, the

term ‘beyond’ betokens merely an imagi-

nary place in a picture we can form of

other dimensions stretching beyond those

of the body of heavens. (Summa Theolog-

ica 1a, 46, 1)

This means that God’s eternity should not be

understood as some sort of everlasting existence of

the same kind as human existence. God’s eternity

is a dimension other than that of human time. For

this reason the biblical statement that God is be-

fore creation should not be understood in a tem-

poral way. It must be admitted, however, that it

seems almost impossible to clarify this nontempo-

ral use of before, although “logically before” must

be a part of the meaning. But if the reality of a spir-

itual world is accepted, it is certainly likely there

are relations that cannot be fully explained or un-

derstood by human beings.

Aquinas compared this view with the relation

between the center and the circumference of a cir-

cle. The relation between the center and the cir-

cumference is the same all the way round; in a

similar manner, God relates in the same way to all

times.

Furthermore, since the being of what is

eternal does not pass away, eternity is

present in its presentiality to any time or

instant of time. We may see an example of

sorts in the case of a circle. Although it is

indivisible, it does not co-exist simultane-

ously with any other point as to position,

since it is the order of position that pro-

duces the continuity of the circumference.

On the other hand, the center of the circle,

which is no part of the circumference, is

directly opposed to any given determinate

point on the circumference. Hence, what-

ever is found in any part of time coexists

with what is eternal as being present to it,

although with respect to some other time it

be past or future. (Summa contra gentiles

1, c. 66)

The reality of the tenses

Since antiquity two images of time have been dis-

cussed: the line made up of stationary points and

the flow of a river. Philosophically speaking, these

images correspond to two positions: “being as

timeless” and “being as temporal.” The two posi-

tions can be found in early Indian thought, for

instance, as held in Brahmanism and Buddhism,

respectively. The different schools in the Brah-

manical tradition have maintained that the ultimate

being is timeless (i.e., uncaused, indestructible, be-

ginningless, and endless). Buddhists, on the other

hand, have claimed that being is instantaneous and

that duration is a fiction since according to their

view a thing cannot remain identical at two differ-

ent instants (Balslev, p. 69 ff.).

In classical Greek thought the tension between

the dynamic and the static view of time has been

expressed, for example, by the Aristotelian idea of

time as the number of motion with respect to ear-

lier and later—an idea that comprises both pic-

tures. On the one hand time is linked to motion

(i.e., changes in the world), and on the other hand

time can be conceived as a stationary order of

events represented by numbers. This discussion is

also reflected in Isaac Newton’s (1642–1727) ideas

of time, according to which absolute time “flows

equably without relation to anything external”

(Principia, 1687).

The basic set of concepts for the dynamic un-

derstanding of time are past, present, and future.

After J. M. E. McTaggart’s analysis of time in “The

Unreality of Time” (1908), these concepts (i.e., the

tenses) are called the A-concepts. They are well

suited for describing the flow of time, since the

present time will become past (i.e., flow into past).

The basic set of concepts for the stationary under-

standing of time are before, simultaneously, and

after. Following McTaggart, these are called the B-

concepts, and they seem especially apt for describ-

ing the permanent and temporal order of events.

Philosophers discuss intensively which of the

two conceptions is the more fundamental for the

philosophical description of time. The situation can

be characterized as a debate between two Kuhnian

paradigms: the ideas embodied by the well-

established B-theory, which were for centuries pre-

dominant in philosophical and scientific theories of

time, and the rising A-theory, which in the 1950s

received a fresh impetus due to the advent of the

LetterT.qxd 3/18/03 1:07 PM Page 897

TIME:RELIGIOUS AND PHILOSOPHICAL ASPECTS

— 898—

tense logic formulated by Arthur N. Prior (1914–

1969). Still, many researchers do not want to em-

brace the A-conception. According to A-theorists,

the tenses are real, whereas B-theorists consider

tenses to be secondary and unreal. According to

the A-theory the “Now” is real and objective,

whereas the B-theories consider the “Now” to be

purely subjective.

Following the ideas of Aquinas, some argue

that time from God’s perspective should be under-

stood in terms of B-concepts because time is given

to God in a timeless way. But it should be men-

tioned that Aquinas also maintained that divine

knowledge can be transformed into the temporal

dimension by means of prophecies. It seems that

Aquinas was suggesting a distinction between time

as it is for temporal beings such as humans and

time as it is for God, who is eternal. However, this

does not answer the important question: Are the

tenses real? Is the “Now” real?

Most writers in Christian philosophy defend

the view that “my Now,” “my present choice,” or

“my present awareness” actually represents some-

thing real. This will lead most writers in Christian

philosophy to the A-theory. They normally find it

obvious that the concept of time has to be related

to the human mind. Therefore it becomes more

natural to describe time by means of tenses (past,

present, and future) than by means of instants

(dates, clock-time, etc.). With tenses, one can ex-

press that the past is forever lost and the future is

not yet here. Without these ideas one cannot hope

to grasp the idea of the passing of time. Phenom-

ena such as memory, experience, observation, an-

ticipation, and hope are all essential for the way

time is understood. Notions of past and future

time, the interpretation of the past, and expecta-

tions of the future are all interwoven in the human

mind. Nevertheless, A-theorists claim that the dis-

tinction between past and future is objective, or at

least intersubjective.

Human freedom and divine foreknowledge

During the Middle Ages logicians felt that they had

something important to offer with regard to solving

fundamental questions in theology. The most im-

portant question of that kind was the problem of

the contingent future. The intellectuals of the Mid-

dle Ages saw the problem as intimately connected

with the relation between two fundamental Christ-

ian dogmas: human freedom and God’s omnis-

cience. God’s omniscience is assumed to comprise

knowledge of future choices to be made by human

beings but apparently gives rise to a straightforward

argument from divine foreknowledge to necessity

of the future: If God already knows the decision

one will make tomorrow, then there is already now

an inevitable truth about one’s choice tomorrow.

Hence, there seems to be no basis for the claim that

one has a free choice, a conclusion that violates the

dogma of human freedom. The argument proceeds

in two phases: first from divine foreknowledge to

necessity of the future, and from that argument to

the subsequent conclusion that there can be no real

human freedom of choice. The problem obviously

bears on the theological task of clarifying questions

such as “In which way can God know the future?”

or “What is to be understood by free will and free-

dom of choice?” In his treatise De eventu futurorum,

Richard of Lavenham (c. 1380) suggested a system-

atical overview of basic approaches to the problem:

If two dogmas are seemingly contradictory, then

one can solve the problem by denying one of the

dogmas or by showing that the apparent contradic-

tion is not real (Øhrstrøm and Hasle, p. 87 ff.).

Denial of the dogma of human freedom leads

to fatalism (first solution). Denial of the dogma of

God’s foreknowledge can either be based on the

claim that God does not know the truth about the

future (second solution) or the assumption that

there is no truth about the contingent future since

nothing has yet been decided (third solution). One

can alternatively demonstrate that the two dogmas,

rightly understood, can be united in a consistent

way (fourth solution). The first two solutions were

seen as contrary to Christian belief, according to

which humans are free at least to a certain degree,

and according to which God knows all truth. Peter

Aureole (c.1280–1322) is notable among the de-

fenders of the third solution. He claimed that nei-

ther the statement “the Antichrist will come” nor

the statement “the Antichrist will not come” is true,

whereas the disjunction of the two statements is

actually true. From that point of view, one can nat-

urally claim that the dogma of God’s omniscience

is still tenable, even if God does not know if the

Antichrist will come or not. God knows all the

truths given and cannot know if the Antichrist will

come due to the simple reason that no truth about

the Antichrist’s future decisions yet exists. In mod-

LetterT.qxd 3/18/03 1:07 PM Page 898

TIME:RELIGIOUS AND PHILOSOPHICAL ASPECTS

— 899—

ern philosophy, this third solution has been de-

fended by Prior and by Charles Sanders Peirce

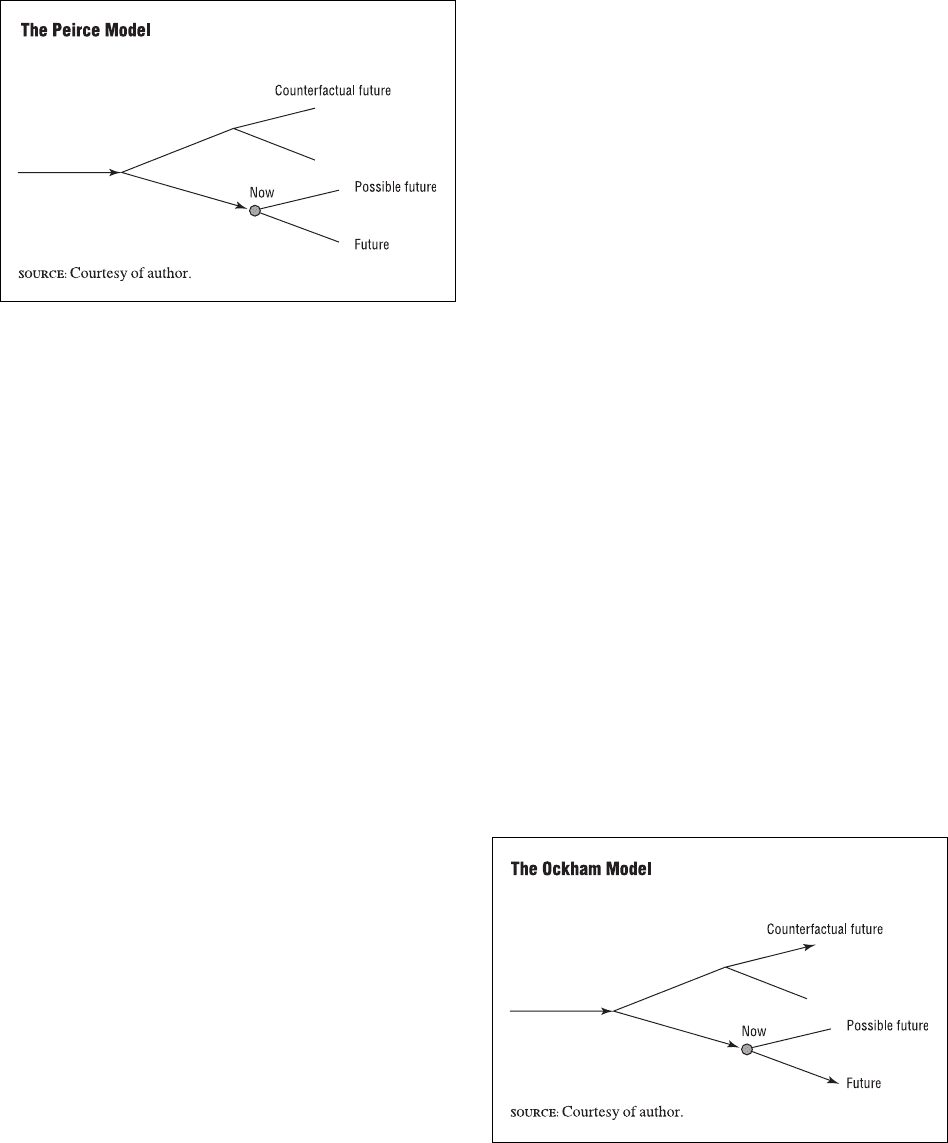

(1839–1914). This idea of a totally open future is

often illustrated using a branching time model:

The central feature of the fourth solution is its

use of the notion of a “true future” among a num-

ber of possible futures. This solution was originally

formulated by William of Ockham (c. 1284–1347).

He discussed the problem of divine foreknowledge

and human freedom in his work Tractatus de

praedestinatione et de futuris contingentibus. He

asserted that God knows all future contingents, but

he also maintained that human beings can choose

between alternative possibilities. Ockham was

aware that considerations on the communication

from God to human beings are essential. God can

communicate the truth about the future to human

beings. Nevertheless, according to Ockham, divine

knowledge regarding future contingents does not

imply that they are necessary. As an example, Ock-

ham considered the prophecy of Jonah: “Yet forty

days, and Nineveh shall be overthrown” ( Jonah

3:4). This prophecy is a communication from God

regarding the future. Therefore, it might seem to

follow that when this prophecy has been pro-

claimed, then the future destruction of Nineveh is

necessary. But Ockham did not accept that. Instead,

he made room for human freedom in the face of

true prophecies by assuming that “all prophecies

about future contingents were conditionals” (Ock-

ham, p. 44). So, according to Ockham, the proph-

ecy of Jonah must be understood as presupposing

the condition “unless the citizens of Nineveh re-

pent.” Obviously, this is exactly how the citizens of

Nineveh understood the statement of Jonah.

The Peirce Model

Ockham realized that the revelation of the fu-

ture by means of an unconditional statement,

communicated from God to the prophet, is incom-

patible with the contingency of the prophecy. If

God reveals the future by means of unconditional

statements, then the future is inevitable, since the

divine revelation must be true. The concept of di-

vine communication (revelation) must be taken

into consideration, if the belief in divine fore-

knowledge is to be compatible with the belief in

the freedom of human actions. However, Ockham

had to admit that it is impossible to express clearly

the way in which God knows future contingents.

He also had to conclude that, in general, divine

knowledge about the contingent future is inacces-

sible. God is able to communicate the truth about

the future to human beings, but if God reveals the

truth about the future by means of unconditional

statements, the future statements cannot be contin-

gent anymore. Hence, God’s unconditional fore-

knowledge regarding future contingents is in prin-

ciple not revealed, whereas conditionals can be

communicated to the prophets. Even so, that part

of divine foreknowledge about future contingents,

which is not revealed, must also be considered as

true according to Ockham.

It can be argued that Anselm (1033/34–1109)

had suggested long before Ockham a similar solu-

tion to the problem of divine foreknowledge and

human freedom. Much later, Gottfried Wilhelm

Leibniz (1646–1716) worked out a metaphysics of

time, which from a systematical point of view is

similar to the thoughts of Anselm and Ockham.

The Ockhamistic solution can be illustrated using

the modern notion of “branching time”:

The Ockham Model

LetterT.qxd 3/18/03 1:07 PM Page 899

TIME:RELIGIOUS AND PHILOSOPHICAL ASPECTS

— 900—

From a theological point of view this model

presupposes what has been called middle knowl-

edge, which is God’s knowledge of what every

possible free creature would do under any possi-

ble set of circumstances (Craig, p. 127 ff.).

Toward a common language for the study

of time

In order to gain more knowledge about the tem-

poral aspects of reality, time has to be studied

within many different strands of science. If such

studies are to lead to a deeper understanding of

time itself, various disciplines have to be brought

together in the hope that their findings may form a

new synthesis, even though one should not expect

any ultimate answer regarding the question of the

nature of time. If a synthesis is to succeed, a com-

mon language for the discussion of time has to be

established.

The twentieth century has seen a most striking

rediscovery of the importance of time and tense.

This is first and foremost due to the work of Arthur

Prior, who was deeply inspired by his studies in

ancient and medieval logic. During the 1950s and

1960s Prior laid out the foundation of tense logic

and showed that this important discipline was inti-

mately connected with modal logic. He revived the

medieval attempt at formulating a temporal logic

corresponding to natural language. In doing so, he

also used his symbolic formalism for investigating

the ideas put forward by these logicians. Prior ar-

gued that temporal logic is fundamental for under-

standing and describing the world in which human

beings live. He regarded tense and modal logic as

particularly relevant to a number of important the-

ological as well as philosophical problems. The

main parts of temporal logic have been developed

using mathematical symbolism and calculus, but

nevertheless it has first and foremost been a philo-

sophical enterprise.

According to Augustine, all humans have a

tacit knowledge of what time is, even though they

cannot define time. In a sense, the endeavor of

temporal logic is to study some manifestations

of this tacit knowledge. The concept of time can

in fact be studied using temporal logic. It seems

likely that Prior’s tense logic may become a crucial

part of a common language for the discussion

of time.

In his temporal logic Prior, among many other

things, took the uncertainty of the future into ac-

count. This means that it is assumed that no de-

scription of the future can be complete because it

must be discussed in terms of open statements and

ambiguous expressions. The reason is that some

future events cannot be specified fully and satis-

factorily in terms of the present vocabulary. In his

temporal logic Prior suggested a notion of un-

statability. According to this idea, the language

needed for a proper description of the temporal

world is growing, and present events can be de-

scribed more fully than was possible earlier when

the events were still part of the future.

See also T = 0; TIME: PHYSICAL AND BIOLOGICAL

ASPECTS

Bibliography

Ariotti, P. E. “The Concept of Time in Western Antiquity.”

In The Study of Time: Proceedings of the Conference

of the International Society for the Study of Time, Vol.

2, ed. J. T. Fraser and N. Lawrence. Berlin and New

York: Springer-Verlag, 1975.

Augustine. The City of God Against the Pagans (De Civi-

tate Dei), 7 vols. Vol. 4 (Books 12–15), trans. Philip

Levine. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press,

1957–1972.

Balslev, Anindita Niyogi. A Study of Time in Indian Philos-

ophy. Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz, 1983.

Craig, William Lane. The Only Wise God: The Compatibil-

ity of Divine Foreknowledge and Human Freedom.

Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Book House, 1987.

Gale, Richard M. The Philosophy of Time: A Collection of Es-

says. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1968.

Goldman, S. L. “On Beginnings and Endings in Medieval

Judaism and Islam.” In The Study of Time IV, ed. J. T.

Fraser. Berlin and New York: Springer-Verlag, 1981.

McTaggart, J. M. E. “The Unreality of Time.” Mind 17

(1908): 457–474.

Øhrstrøm, Peter, and Per, Hasle. Temporal Logic: From

Ancient Ideas to Artificial Intelligence. Boston and

Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer, 1995.

Prior, Arthur N. Past, Present, and Future. Oxford: Claren-

don Press, 1967.

Prior, Arthur N. Papers on Time and Tense. Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1968.

Thomas Aquinas. Summa theologiae, ed. Timothy McDer-

mott. London: Blackfriars, 1970.

LetterT.qxd 3/18/03 1:07 PM Page 900

TRUTH,THEORIES OF

— 901—

Thomas Aquinas. Summa contra gentiles, trans. Anton C.

Pegis; J. F. Anderson; V. J. Bourke; and C. J. O’Neil.

Notre Dame, Ind.: Notre Dame University Press, 1975.

Whitrow, G. J. What is Time? London: Thames and Hud-

son, 1972.

William of Ockham. Predestination, God’s Foreknowledge,

and Future Contingents, trans. Marilyn McCord

Adams and Norman Kretzmann, New York: Apple-

ton, 1969.

PETER ØHRSTRØM

TOP-DOWN CAUSATION

See DOWNWARD CAUSATION

TRANSCENDENCE

The term transcendence, from the Latin transcen-

dere (to climb up), means to go beyond, surpass,

or rise above, particularly what is given in personal

experience. In theology, transcendence is associ-

ated with the beyondness and holiness of God, in

the sense of the existence of God being prior to

the physical cosmos and exhalted above it. Refer-

ring to divine ascent beyond the world, transcen-

dence is frequently contrasted with immanence,

the presence of God in the world. Historically,

deism emphasized total transcendence of the

world while pantheism stressed the total imma-

nence of God in the world. Most theistic traditions

seek a balance between the two.

See also DEISM; GOD; HUMAN NATURE, RELIGIOUS AND

PHILOSOPHICAL ASPECTS; IMMANENCE; PANTHEISM

ERNEST SIMMONS

TRANSMIGRATION

The term transmigration, from the Latin transmi-

grare (to migrate across or over), means to pass

from one condition, place, or body to another.

Transmigration is usually identified with the Greek

word metempsychosis (change of soul), the “trans-

migration of souls” drawing on the Greek Orphic

mysteries. In South Asian religions, transmigration

is related to the karmic cycle where one’s moral

action determines the condition of the soul and

the quality of its rebirth. In Hinduism, the cycle of

rebirth is eternal unless the soul is liberated (mok-

sha) by knowledge or arduous effort (Yoga). In

Buddhism the soul and transmigration are ulti-

mately illusory (maya), being passing emergents

from samsara, the eternal, undifferentiated stream

of being.

See also KARMA; LIFE AFTER DEATH

ERNEST SIMMONS

TRUTH,THEORIES OF

The question of truth is inherent in human ration-

ality. A core feature of rationality is self-reflection

in the sense that we can critically reflect upon how

we see the world. In the question of truth our re-

lation to reality is called into question, and the pur-

suit of truth is therefore pivotal to both science

and religion.

When we are asking for a theory of truth, we

take a step back and focus on our conception of

truth. The first thing to be noted is that we use the

word true as an adjective for various things: A

statement can be true, but so can a friend or an act

of friendship, or a democracy. In the latter cases

we may substitute real for true: A true friend is a

real friend whom we can count on. But if the sen-

tence “She is a true friend” is true, it is so in a sense

where we cannot substitute real for true. This in-

dicates that a theory of truth deals with mental acts

(e.g., beliefs) or statements (judgments, proposi-

tions) as truth bearers. Mental acts or statements

are about something. A theory of truth thus oper-

ates at the level where we relate to something, and

relate in such way that we make truth claims about

what we relate to (i.e., claims as to what it is and

how it is). The key issue for a theory of truth is the

relation between beliefs or statements that can be

true or false, and that which these beliefs or state-

ments are about. We can then distinguish between

the following types of truth theories: the corre-

spondence theory, the coherence theory, and

pragmatic theories.

LetterT.qxd 3/18/03 1:07 PM Page 901

TRUTH,THEORIES OF

— 902—

Correspondence theory of truth

According to a correspondence theory of truth, the

truth relation is a correspondence between a state-

ment and a fact. A theory of this kind reflects a

commonsense idea of truth to the effect that a

statement is true if it corresponds to how things ac-

tually are. This is captured in the classic formula-

tion of the correspondence theory in Aristotle

(384–322

B.

C.E.): “To say of what is that it is not, or

of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of

what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is

true” (Aristotle, 1011b26f). Thus, truth means

agreement with reality. However, a statement can-

not correspond to a thing or an event. In order to

ascertain whether a statement is true or false we

need to know what it is about, that is, what the

thing or the event in question is. What makes a

statement p (e.g., “He was late”) true is the fact of

p (i.e., that he actually was late). Correspondence

is thus correlation between statements and facts. It

need not be congruence, however, in the sense

that the structure of the statement somehow re-

flects the structure of the fact.

But this does not solve the problem of expli-

cating what it is that statements correspond to. We

do not have two separate entities, statements, and

facts. It might be argued that facts are what true

statements state, not what they are about. And if

we are going to determine what the fact is to

which the statement corresponds—in order to

compare statement and fact—then we must make

another statement. Thus, the relation between

statements and reality can only be determined by

other statements.

Coherence theory of truth

A coherence theory of truth seeks to meet this

problem by transforming correspondence between

statement and fact into coherence between state-

ments. A statement or belief is true to the degree it

coheres with other accepted statements or beliefs

related to it, or to be more precise, if it fits into the

most coherent set or system of statements or be-

liefs. What is required for a set of statements or be-

liefs to be coherent is internal consistency, or even

mutual entailment between the statements or be-

liefs in question. To this can be added the further

requirement that the system not only is coherent,

but also gives the most complete picture of the

world. Thus, the argument for a coherence theory

not only is that a statement can only be compared

to other statements, but also that a statement or a

belief never is without context: It presupposes

other statements in order to be true, and it does so

because a thing is what it is due to its relations to

other things. Consequently, a coherence theory of

truth often is linked to a metaphysics according to

which reality basically is a coherent system. But the

context can also be construed as a system of inter-

pretations that we presuppose when making a

statement. We can only compare interpretations

with other interpretations. A coherence theory thus

favors an antirealist ontology to the effect that there

is no mind-independent or extralinguistic reality.

The coherence solution however engenders

problems of its own. First, standard versions of the

coherence theory confuse the meaning of truth

(the definition) with the criterion of truth (the test).

Second, it seems possible to have two internally

coherent, but mutually inconsistent sets of beliefs

concerning the same reality. The further require-

ment that a coherent system must also give the

most complete picture of the world implies that we

should be able to compare competing sets of be-

liefs as interpretations of the same world. Third, if

a statement is true when it coheres with what we

already accept to be true, how do we decide the

truth of these other statements or beliefs, upon

which the first statement depends? And how is our

view of reality changed?

Pragmatic theories of truth

A pragmatic theory of truth takes a step further by

focusing on the social context of understanding.

One version is a consensus theory that translates

the meaning of truth into the context of argumen-

tation. It is not sufficient to say that a statement is

true if it coheres with our accepted views. A

stronger condition is that a statement is true if it is

accepted by the most informed participants or by

everyone with sufficient relevant experiences to

judge it. But if truth amounts to what the most in-

formed participants or everyone sufficiently expe-

rienced agree upon, the question is how to decide

who are the most informed participants or when

we are sufficiently experienced. In order to avoid

this problem, the criterion of consensus can be

made both stronger and more open-ended: If truth

is what everybody will ultimately agree upon, a

theory of consensus can place some stronger con-

ditions on what is meant by ultimately.

LetterT.qxd 3/18/03 1:07 PM Page 902

TRUTH,THEORIES OF

— 903—

Jürgen Habermas (1929– ) reformulates the

consensus theory as a discourse theory: The mean-

ing of truth is “warranted assertibility.” Statements

are true if their truth claims are warranted in a dis-

course in which we only enter by presupposing an

ideal situation of communication where no partic-

ipant is in a privileged position. Truth is thus de-

fined in the context of argumentation in which we

meet various or even conflicting truth claims that

are open to discussion in a discourse. But if the

meaning of truth is defined by the procedure of ar-

gumentation, this procedure cannot recur to the

concept of truth. If truth is translated into the con-

sensus to be reached, this consensus cannot in

turn be measured by truth. The argumentation in a

discourse about truth claims, however, is not about

consensus but about truth. If it aims at consensus,

it is a consensus concerning what the truth is. Con-

sequently, there remains a normative dimension of

truth, which in Habermas is translated into the

ideal situation of communication.

A second version of a pragmatic theory of truth

is an instrumentalist theory that measures the truth

of beliefs or statements by their consequences:

“That which guides us truly is true—demonstrated

capacity for such guidance is precisely what is

meant by truth. . . . The hypothesis that works is

the true one; and truth is an abstract noun applied

to the collection of cases, actual, foreseen and de-

sired, that receive confirmation in their works and

consequences” (Dewey, p. 156–157). The problem

here is how to decide what truly means. The ref-

erence to consequences is in need of qualification

as to which consequences would meet the re-

quirement of guiding us truly. In fact, an instru-

mentalist theory substitutes utility for truth.

As an alternative to an instrumentalist theory

(“The truth is what works”), the central pragmatist

idea can be reformulated in a performative theory

of truth that focuses on what we are doing when

we take something to be true. This is outlined by

Robert B. Brandom (1950– ) in a model that em-

phasizes the act of calling something true rather

than the descriptive content of truth statements. It

further gives an account of that act in terms of a

normative attitude: Taking some claim to be true is

committing oneself to it. Endorsing a truth claim is

understood as adopting it as a guide to action, and

the correctness of adopting it can be measured by

the success of the actions it guides (involving here

what Brandom calls “stereotypical” pragmatism).

Once we have understood acts of “taking-true” ac-

cording to this model, we have “understood all

there is to understand about truth.” This means that

truth “is treated, not as a property independent of

our attitudes, to which they must eventually an-

swer, but rather as a creature of taking-true or

treating-as-true” (Brandom, p. 287). This performa-

tive analysis of truth talk in terms of a theory of

“taking-true” can be combined with a redundancy

theory of truth: When we state “It is true that p,”

we only make explicit the claim implicit in stating

p. In calling the statement p true, we are not de-

scribing a property of that statement. We are doing

something—we are committing ourselves.

A pragmatic theory of truth takes as its point of

departure that there is no absolute or universal

truth at our disposal. Still, as we have seen, a prag-

matic theory can maintain and seek to account for

the normative dimension of truth. It here differs

from a radical instrumentalist theory according to

which truth is a fiction in the sense of human con-

struction. According to Friedrich Nietzsche

(1844–1900), truth is not something to be found

but something to be created. Although, in Niet-

zsche, truth is itself illusion, fiction, or construc-

tion, there still seems to be a normative dimension

unaccounted for in his unmasking of illusions.

Truth in religion

Coherence and pragmatic theories of truth derive

much of their plausibility from the ambition to

avoid the problems facing a correspondence the-

ory. However, the question is whether we can do

without a strong normative concept of truth that

reflects the experience of a reality not correspon-

ding to our beliefs or interpretations. Truth as an

open question implies a strong concept of truth in

the sense that we ourselves have to experience

whether our beliefs are true or not. The key issue

in theories of truth can be reformulated as the re-

lation between our cognitive attitudes and reality.

The challenge facing us is to account both for the

fact that we do not have access to a reality outside

of our attitudes or our interpretations of reality,

and for the normative dimension of truth. The line

of argument has led from descriptive attitudes that

consider the world from outside to cognitive atti-

tudes embedded in social practices in which we

partake in the reality we are talking about. Truth

claims can be implicit in nondescriptive attitudes.

LetterT.qxd 3/18/03 1:07 PM Page 903

TURING TEST

— 904—

When we are talking about the world we are not

only describing how things are, but we are relating

to the world in various ways.

That truth is a question of how we relate to the

world is brought out in what can be called an ex-

istential conception of truth, which should not be

confused with an existentialist or subjectivist re-

duction of truth. According to Søren Kierkegaard

(1813–1855), “the truth is only for the individual in

that he produces it in action,” but in the same vein

it is stated that “the truth makes a human being

free” (1980, p. 138). The dictum that “subjectivity is

truth” (Kierkegaard, 1992, p. 240) does not mean

that each of us freely chooses what should count

as the truth. The point is conversely that subjectiv-

ity itself is to be determined by the truth. Taking

something to be true implies that it should deter-

mine the way we relate to ourselves and to others.

This leads to the issue of truth in religion. The

truth question is basic not only to the rational in-

quiry into nature, but also to the understanding of

religion. Indeed, the issue of rationality and reli-

gion turns on the question of truth. What happens

when the question of truth is seen within the con-

text of religion? First, the tension between uncer-

tainty (implicit in asking the question) and cer-

tainty (in answering it) is intensified: What is meant

by the truth in view of conflicting truth claims? Sec-

ond, religion represents a double possibility. It can

suspend the truth question by giving an answer to

it that is not open for discussion, but it can also re-

open the truth question by calling our attitudes

and self-understanding into question. Third, in re-

ligion, the relation between cognitive attitudes, on

the one hand, and volitional and affective attitudes

on the other, and between attitudes and action, is

complicated. To believe in the truth implies that

we understand ourselves in the light of the truth,

which means that it should form our life. Fourth,

what religion can do is reverse the perspective:

The truth question is not only a question for us to

decide, but also calls into question how we relate

to the world. When religion speaks of the truth, it

is also implied that truth is not at our disposal, but

conversely questions us: What is the truth about

us? The truth question is also disturbing when it

calls into question who we, the subjects of the

question, are.

See also IDEALISM; PLATO; PRAGMATISM; REALISM

Bibliography

Aristotle. Metaphysics. In The Works of Aristotle, Vol. 8,

trans. W. D. Ross. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1972.

Blanshard, Brand. The Nature of Thought. New York:

Macmillan, 1941.

Brandom, Robert B. Making It Explicit: Reasoning, Repre-

senting and Discursive Commitment. Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1994.

Dewey, John. Reconstruction in Philosophy Boston: Bea-

con Press, 1985.

Habermas, Jürgen. “Wahrheitstheorien.” In Vorstudien und

Ergänzungen zur Theorie des kommunikativen Han-

delns. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp, 1984.

Kierkegaard, Søren. The Concept of Anxiety: A Simple Psy-

chologically Orienting Deliberation on the Dogmatic

Issue of Hereditary Sin. In Kierkegaard’s Writings,

Vol. 8, trans. and ed. Howard V. Hong and Edna H.

Hong. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press,

1980.

Kierkegaard, Søren. Concluding Unscientific Postscript. In

Kierkegaard’s Writings, Vol. 7.1, trans. and ed.

Howard V. Hong, and Edna H. Hong. Princeton, N.J.:

Princeton University Press, 1992.

Kirkham, Richard L. Theories of Truth: A Critical Introduc-

tion. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1992.

Peirce, Charles S. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders

Peirce, ed. Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss. Cam-

bridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1931–1958.

Skirbekk, Gunnar. Wahrheitstheorien. Frankfurt am Main,

Germany: Suhrkamp, 1977.

ARNE GRØN

TURING TEST

The Turing Test was proposed by computer pio-

neer Alan M. Turing (1912–1954) to determine

whether a computer program is intelligent. This

modern interpretation of the so-called imitation

game is based on a setup where a person, a com-

puter, and an interrogator are in three separate

rooms and connected via computer terminals. The

task of the interrogator is to figure out by asking

questions which of the two connected terminals is

operated by the human and which is the test com-

puter. The computer is considered to be intelligent

if the interrogator fails to determine its identity.

LetterT.qxd 3/18/03 1:07 PM Page 904

TWO BOOKS

— 905—

The Turing Test is recognized as a critical test for

computer intelligence and, as of 2002, had not

been passed by any computer.

See also ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE; THINKING MACHINES

THIEMO KRINK

TWO BOOKS

Permeating the Western Christian tradition of natu-

ral theology is a metaphor expressing the belief

that God is revealed in a complementary pair of

sources: the book of scripture and the book of na-

ture. The idea of nature as a book was used by

early modern writers as shorthand for the design

argument for God’s existence. Thomas Browne

(1605–1682), for example, wrote, “There are two

books from whence I collect my divinity: besides

that written one of God, another of his servant, na-

ture, that universal and public manuscript that

lies expansed unto the eyes of all” (Religio

Medici I.16).

Origins of the metaphor

The metaphor was born at the confluence of a

number of streams: the common human experi-

ence of the transcendent, the conviction of the re-

ality of divine-human communication, and the

Western fascination for books as repositories of

knowledge. The conviction that God is made

known through divine works is celebrated in

Psalm 19, and Wisdom 11: 6–9 articulates the idea

that even gentiles who have not enjoyed the bene-

fit of revelation are without excuse for their unbe-

lief, a tradition persisting at least until the time of

John Calvin (1509–1564). The New Testament locus

classicus for the natural knowledge of God is the

Pauline declaration, “For what can be known about

God is plain to them, because God has shown it to

them. Ever since the creation of the world his in-

visible nature, namely, his eternal power and deity,

has been clearly perceived in the things that have

been made” (Romans 1:19–20).

The elements of what would become the

“book of nature” metaphor are scattered through-

out Patristic literature. Justin Martyr (c. 100–165)

built his second-century apologetic upon the Stoic

idea of the logos spermatikos, arguing that the

world is permeated by seeds of the divine word

(Second Apology VIII), and Irenaeus (c. 130–200)

provided the two essential ingredients of the

theme in the works and the word of God (Adver-

sus haereses, Book I, ch. 20). Tertullian (c. 160–

225) regarded the works of God as an important

revelatory counterpart to the Bible (Adversus Mar-

cionem, Book II, ch. 3). For Augustine of Hippo

(354–430) the book of the heavens provided milk

for the spiritually immature (Confessions, Book

XIII, ch. 18.23, 26). The closest thing to a formal

Patristic statement of the metaphor of “the book of

nature” may be found in John Chrysostom’s (c.

347–407) Homilies to the people of Antioch, in

which he declared that nature serves the function

of a book of revelation: “Upon this volume the un-

learned, as well as the wise man, shall be able to

look, and wherever any one may chance to come,

there looking upwards towards the heavens, he

will receive a sufficient lesson from the view of

them. . . .” (Homily IX. 5).

The metaphor became firmly established in the

Middle Ages, expressing a mature binary episte-

mology of revelation. Alain of Lille (c. 1128–1203)

held every created thing to be like a book; Hugh of

Saint Victor (1096–1142) regarded both the cre-

ation and the incarnation as “books” of God, com-

paring Christ—as primary revelation—to a book.

Bonaventure (c. 1217–1274) suggested that there

are three volumes: sensible creatures are “a book

with writing front and back,” spiritual creatures are

“a scroll written from within,” and scripture is “a

scroll written within and without” (Collations on

the Hexaemeron 12.14–17). For Thomas Aquinas

(c. 1225–1274) the first element of the threefold

knowledge of divine things is “an ascent through

creatures to the knowledge of God by the natural

light of reason” (Summa Contra Gentiles, IV.1.3).

For the poet Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), the god-

head is the book in which all the loose pages scat-

tered throughout the universe will eschatologically

be bound in one volume (Paradiso XXXIII). Ray-

mond of Sabunde (d. 1436) gave the metaphor its

fullest medieval articulation in his Theologia Natu-

ralis sive Liber Creaturarum. He regarded every

created thing as a letter written by the finger of

God, and human beings as the first letters of this

book. His work attracted the attention of the cen-

sors, however, because of his incautious opinion

that the book of nature is more accurate than

LetterT.qxd 3/18/03 1:07 PM Page 905

TWO BOOKS

— 906—

the Bible, and his assertion of the preeminent

importance of natural knowledge; it was placed on

the Index (the official list of books prohibited by

the Roman Catholic church) in 1595.

Early modern variations on the theme

The “book of nature” enjoyed its greatest currency

in the early modern period. The emphasis of the

Reformers on the literal sense of scripture cut

through the profusion of “meanings” and “signa-

tures” found by medieval scholars in nature and re-

inforced the idea of there being two books. How-

ever, the book of nature was clearly subordinate to

biblical revelation in Calvin’s theology, which held

scripture to be a necessary corrective to the defi-

ciencies of nature (Institutes I.6.1). The Reformed

tradition retained this Calvinist interpretation of the

two books in the Belgic Confession adopted by the

Dutch Reformed Church. In contrast, Paracelsus

(1493–1541) suggested an empirical approach:

Whereas scripture was to be explored through its

letters, the book of nature had to be read by going

from land to land, since every country was a dif-

ferent page.

The metaphor was affected in the seventeenth

century by both the elaboration of natural theology

and the development of the sciences in novel em-

pirical and theoretical directions. Pierre Gassendi

(1592–1655) saw purpose in all of nature and sug-

gested that if René Descartes (1596–1650) wanted

to prove the existence of God, he ought to aban-

don reason and look around him, and that the two

books were not to be kept on separate shelves. Al-

though Francis Bacon (1561–1626) seems in prac-

tice to have kept the two books distinct, he articu-

lated their essential complementarity:

The scriptures reveal to us the will of God;

and the book of the creatures expresses the

divine power; whereof the latter is a key

unto the former: not only opening our un-

derstanding to conceive the true sense of

the scriptures, by the general notions of

reason and rules of speech; but chiefly

opening our belief, in drawing us into a

due meditation of the omnipotency of God,

which is chiefly signed and engraven upon

his works. (The Advancement of Learning

VI, 16)

Bacon set the tone for the seventeenth-century

scientific enterprise in his redirection of the “two

books” metaphor toward the improvement of the

human estate.

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) argued that the

book of nature is written in the language of math-

ematics, not only implying that mathematics is the

sublimest expression of the divine word, but de

facto restricting its full comprehension to those

who are appropriately educated:

And to prohibit the whole science [of as-

tronomy] would be but to censure a hun-

dred passages of holy Scripture which

teach us that the glory and greatness of

Almighty God are marvelously discerned

in all his works and divinely read in the

open book of heaven. . . . Within its pages

are couched mysteries so profound and

concepts so sublime that the vigils, labors,

and studies of hundreds upon hundreds of

the most acute minds have still not pierced

them, even after continual investigations

for thousands of years. (Letter to Grand

Duchess Christina)

Galileo’s famous dictum that scripture teaches

“how one goes to heaven, not how heaven goes”

should be interpreted in light of his conviction of

the complementarity of the two books.

The metaphor flourished in the natural theo-

logical climate of seventeenth-century England,

particularly in the “physico-theology” of the Boyle

Lectures. But its two terms were not always held in

comfortable balance. The dissenting theologian

Richard Baxter (1615–1691), for example, argued

that “nature was a ‘hard book’ which few could

understand, and that it was therefore safer to rely

more heavily on Scripture” (The Reasons for the

Christian Religion, 1667). In contrast, Isaac New-

ton (1642–1727) saw nature as perhaps more truly

the source of divine revelation than the Bible, al-

though he spent decades of his life investigating

the prophetic books. Frank Manuel, in The Reli-

gion of Isaac Newton (1974), argues that in virtually

abolishing the distinction between the two books,

which Newton revered as separate expressions of

the same divine meaning, Newton was attempting

to keep science sacred and to reveal scientific ra-

tionality in what was once a purely sacral realm,

namely, biblical prophecy. By the early eighteenth

century there was a significant faction within the

Royal Society opposed to any mention of scripture

in a scientific context.

LetterT.qxd 3/18/03 1:07 PM Page 906