The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

GROWTH AND CHANGE IN THE ECONOMY 21

provide capital necessary for modern industry. It tended to smother

merchants and gentry whom it took into partnership, and failed to create

financial and other conditions favourable to economic growth.

35

Similar

inadequacies appeared in the 'bureaucratic capitalism' practised under

the Nanking government in the 1920s and 1930s and plagued even

disinterested efforts at reform. Attempts to improve silkworm strains and

silk-production methods, for instance, were hampered because the

government had neither the means to enforce its policies nor the

confidence of the local populace.

In sum, the technological and distributive factors seem to have

reinforced one another so as to keep economic change within moderate

limits,

unable to break through the existing equilibria. Change was

occurring, but in the absence of a major revamping of the rural sector

—

of

an 'agricultural revolution' Chinese style —it appears unlikely that

continuing commercialization, further concentration of capital in the

Lower Yangtze, or growth of the considerable, if technically illegal, trade

with South-East Asia would have soon led to a radical reorganization of

the economy. As it was, the major impetus came from abroad.

External

factors•:

foreign trade and imperialism

Virtually all historians assume that Western imperialism had an effect on

Chinese economic growth; but they differ over the weight and timing of

its effect and whether it had a negative or positive influence. One line of

analysis suggests that foreign activity played a crucial role in fostering

sustained industrial development in the late nineteenth and twentieth

centuries. Foreign industry in the treaty ports provided capital equipment

and stimulated Chinese enterprise. Loans provided capital to modernize

transportation and communications and establish heavy industry.

Foreigners were the source of new technical knowledge. In short, an

exogenous shock was needed to overcome the inertia of the Chinese

economy and concentrate necessary resources.

36

Chinese Marxist-Leninist and other historians, on the contrary, have

argued that from the time of the Opium War imperialism inhibited

internal forces favouring growth and capitalism: imports destroyed

Chinese handicrafts, thus impoverishing peasants and restricting the

" See W. K. K. Chan, CHOC 11.460-2; Wang Hsi, 'Lun wan-Ch'ing ti kuan-tu shang-pan' (On

the system of official supervision and merchant management during the late Ch'ing), LJ-sbib

bsueb

(Historical study), i (1979) 95-124. A much more positive assessment of the Ch'ing state's

economic role appears in Ramon Myers, Tbe

Chinese

economy:

past and present.

56

For this view see Robert Dernberger, "The role of the foreigner in China's economic

development, 1840-1949', in Perkins, ed.

China's modern

economy,

19-48.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

22 INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

domestic market. Chinese merchants were drawn into peripheral and

dependent relations with foreign firms; unequal competition hampered

growth of Chinese industry. Foreign loans and investments drained profits

abroad and led to administrative interference in government finance.

Although China was never ruled by Western foreigners, except in the

treaty ports, Chinese governments were discouraged from promoting

modern industry by fear of foreign seizure by military power. Most

obviously, foreign control of Chinese tariffs prevented their protecting

Chinese industry by excluding foreign competition.

37

A major variant of

this approach argues that expansive capitalist states in search of markets

and resources forced weaker unindustrialized countries into relationships

of dependency, in order to secure the export of their resources for use

by industries of the capitalist states. This perpetuated the economic

underdevelopment of the weaker states, increased inequality both between

social classes and between regions of the world, and to some degree

impoverished peasants in the underdeveloped countries.

38

All these theories, particularly the last, seem to underestimate the

previous level of indigenous commercial development in China. They do

not explain how external factors could be so decisive when the foreign

trade was so small in comparison with the total Chinese economy.

Moveover, even in the twentieth century, the national market was still

imperfectly integrated and many rural economies still produced mainly

for consumption within a limited geographical area, although linked to

markets elsewhere. The common-sense conclusion is that internal and

external factors interacted and their relative importance varied with time,

place, and circumstance. Foreign interests both inhibited and encouraged

Chinese industry, sometimes, as in the case of tobacco, encouraging some

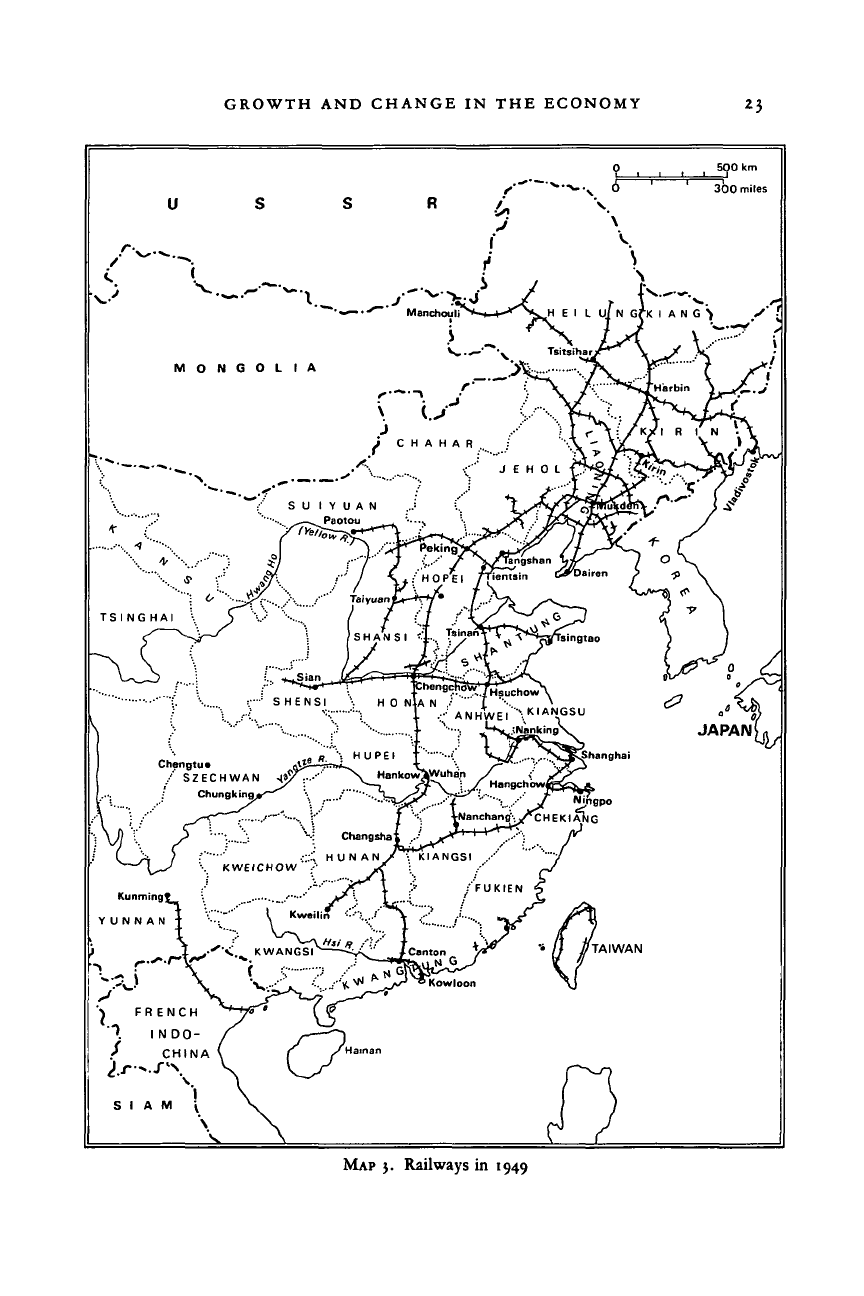

aspects while retarding others. The largely foreign-financed railroad

construction in late Ch 'ing and Republican China did benefit the Chinese

economy despite the context of imperialism within which these railways

were built.

39

In areas where agricultural production remained locally

37

Hu

Sheng, Imperialism

and

Chinese politics, ifyo-rpij

is

one

of

many examples

of

this range

of

views.

38

For general theory

of

underdevelopment see

C

K.

Wilber, ed. Tie political

economy

oj development

and underdevelopment.

A

generalized theory emerges from Wallerstein's concept

of a

capitalist

dominated world economic system (Immanuel Wallerstein,

The

modern world-system: capitalist

agriculture

and

the

origins of the

European world-economy

in

the sixteenth

century

and

subsequent studies).

Brief suggestions

on how

this theory might apply

to

China appear

in

Angus McDonald,

Jr.

'Wallerstein's world economy:

how

seriously should

we

take it?'

JAS

38.3

(May 1979)

535~4°-

There

is

substantial evidence

for

world impact

on

sectors

of the

Chinese economy since

the

sixteenth century

(e.g.

William Atwell, 'Notes

on

silver, foreign trade,

and the

late Ming

economy', CSW'l

3.8 (Dec. 1977)

1-33),

but

thus

far few

detailed studies.

3

« Sherman Cochran, Big

business

in China:

Sino-foreign

rivalry in

the

cigarette industry, iSpo-rpjo, zoi-io.

Ralph William Hueneman, The

dragon

and

the iron horse:

tie

economics

of

railroads

in

China

systematically examines

the

question

of

the economic consequences

of

the railways.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

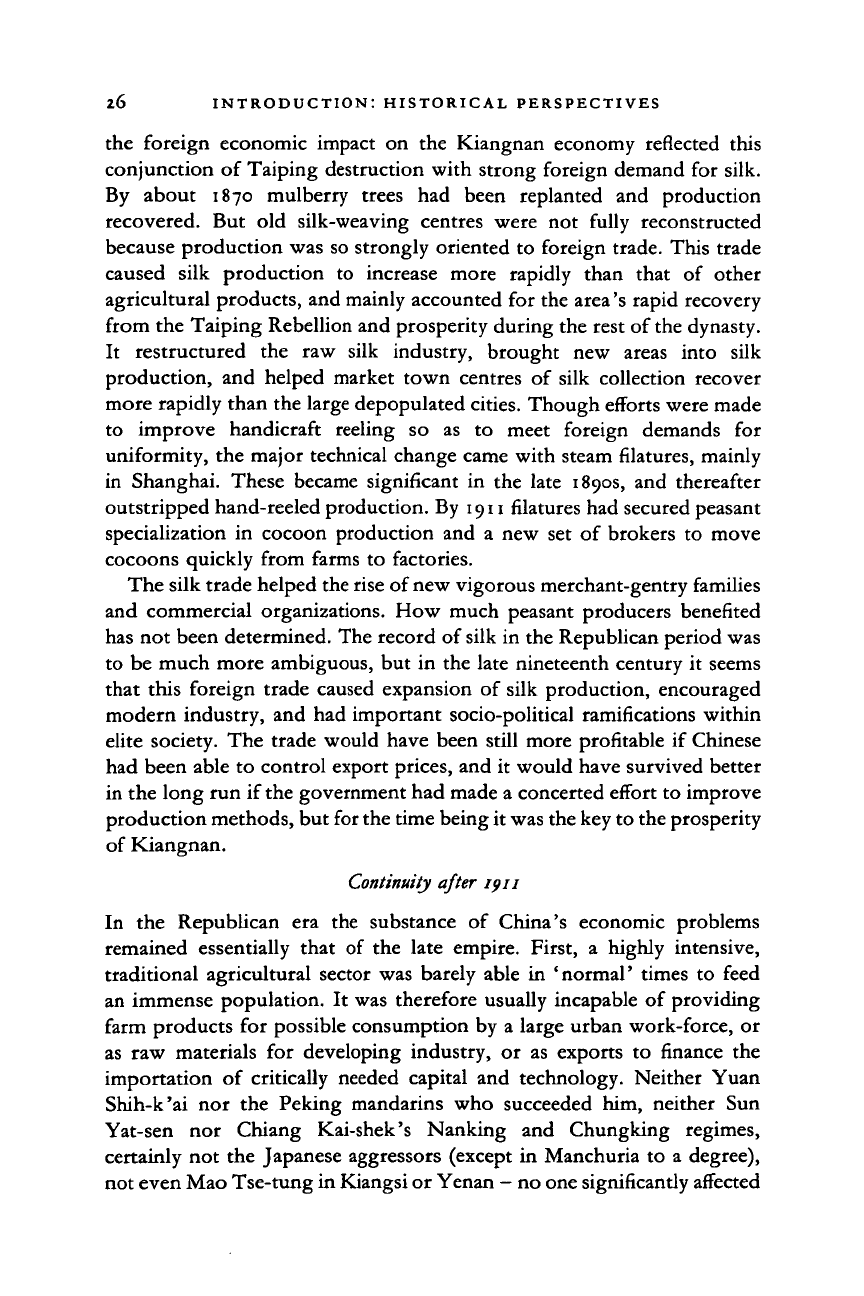

GROWTH AND CHANGE IN THE ECONOMY

59O km

300 miles

u

MONGOLIA

•r.^

•\ FRENCH

•7 IND0-

/ CHINA

S I A M

MAP

3. Railways in 1949

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

24 INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

consumed, foreign trade had little impact. However, it is not necessary

to postulate general economic dependency to recognize that growing

involvement in world trade could have important repercussions. The

stimulus to commerce in the Han River valley caused by export trade from

the 1870s to the 1910s or the brief boom in sugar-cane production in

Haifeng county, Kwangtung, because of a temporary world shortage from

the late 1880s to mid-igoos,

40

showed that effects were not limited to major

cities.

As industrialization proceeded and foreign trade increased, world

economic conditions had a growing effect on the economy in important

parts of China. The ambivalence of this impact of trade and imperialism

can be seen in the relatively well-studied cotton textile and raw silk

industries.

The decline of domestic cotton-spinning in the nineteenth century has

been cited repeatedly to illustrate the adverse impact of imperialism on

nascent Chinese capitalism and peasant livelihood. However, blanket

allegations that textile imports and subsequently foreign factories in China

destroyed rural handicrafts do not hold up. Detailed studies show that

although household spinning largely disappeared it was replaced by

handicraft weaving using foreign yarn. Moreover, yarn for the warp of

looms was still produced by peasant spinners after imports supplied the

weft; in fact hand spinning declined at different times in different localities,

allowing a rather long period for peasant households to adjust.

41

Hand

weaving continued to compete successfully with factories established in

China during the twentieth century because peasant families could still

profit from using their surplus labour even when prices had declined.

Moreover, hand weaving spread to new areas

—

for instance, central

Chekiang at the end of the

Ch

'ing, and parts of north-western and western

China during the Republic - indicating a spread of domestic demand and

penetration of manufactured yarns. On balance weaving was probably

more profitable than spinning, so in the long run the changeover may well

have raised the living standards of many peasants although it probably

lowered the household incomes of even more.

This aggregate, long-term picture obscures local instances of short-run

decline and dislocation. Textile imports initially hurt the highly developed

spinning and weaving handicraft industries of the urbanized Canton delta.

In the 1830s Chinese handwoven exports (Nankeens) declined and a

market grew up for imported foreign yarns. Both weavers and spinners

suffered, and in 1831 a sudden increase in foreign yarn imports triggered

40

Liu

Ts'ui-jung, Trade on

the

Han River and

its

impact on economic development, itoo-ifii; Marks,

'Peasant society', 205—26.

41

Kang Chao, The development

of

cotton

textile production

in

China, 174—86; Bruce Reynolds, 'Weft:

the technological sanctuary

of

Chinese handspun yarn', CSWT

3.2 (Dec.

1974)

4-13.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GROWTH AND CHANGE IN THE ECONOMY 25

a boycott led by spinners. Eventually the textile workers shifted from

spinning to weaving, but the unemployment fostered hostility to

foreigners and the social disruption contributed to the Taiping Rebellion.

42

Handicraft spinning in Haifeng county, further north along the Canton

coast, persisted until the end of the Ch'ing. After it died out between 1890

and 1910, weaving continued under a putting-out system. But modern

mills in Haifeng after 1918 replaced household weaving. Local textile

production overall probably expanded, but the conversion of peasant

family producers into factory wage labourers had unsettling socio-political

consequences.

43

Even where domestic weaving flourished most strongly

in the twentieth century, it was not a stable occupation. Weaving in North

China tended to concentrate in centres that competed with one another

and went through phases of boom and retrenchment from the 1910s to

the 1930s. Fluctuation was caused more by this local competition and by

domestic market conditions than by direct foreign factors until the world

depression of

the

1950s. Japanese occupation of Manchuria later restricted

markets and hastened the decline of the North China centres.

44

Expansion

of the textile industry thus led to different kinds of economic fluctuations

resulting from growth, competition, and international market movements.

Such changes might disrupt village communal patterns and make

handicraft production a less predictable source of income for peasant

families who had to supplement their income from farming.

45

The history of silk production in the Lower Yangtze during the last

seventy years of the Ch'ing shows a more unambiguously expansive

impact of foreign trade.

46

In the late 1840s raw silk exports shifted from

Canton to Shanghai where they expanded rapidly in the

18

5

os

during the

Taiping Rebellion. Cutting off of domestic markets as well as declining

production of the imperial silk factories probably made silk more available

for export. In the early 1860s the rebellion devastated Lower Yangtze

silk-producing areas, causing a sharp drop of exports in 1863-4 and rather

slow recovery during the rest of the decade. For the rest of the century

41

Kang Chao, Textile production, 82, 87-8; Ming-kou Chan, 'Labor and empire: the Chinese labor

movement in the Canton Delta, i895-i9Z7'(Stanfbrd University, Ph.D. dissertation, 1975), 11-12,

367.

43

Marks, 'Peasant society', 231—41. See below, ch.

6

(Bianco).

44

Kang Chao, Textile production, 188-9, 191—101.

45

Linda Grove, 'Creating

a

northern soviet', Modem China,

1.3

(July 197J) 259; Myers, The Chinese

economy, sees market fluctuations

due to

external causes

as

leading

to

unemployment, violence

and economic crisis.

46

The

major English-language work

on the

silk trade

is Li,

China's silk trade.

See

also

Eng,

'Imperialism

and the

Chinese economy'

and E-tu Zen

Sun, 'Sericulture

and

silk production

in Ch'ing China',

in

Willmott, ed., 79—108.

On the

relative expansiveness

of

silk production,

see David Faure,

'

The rural economy

of

Kiangsu province, 1870-1911', Journal

of

the Institute

of Chinese Studies, Chinese University

of

Hong Kong, 9.2 (1978) 380-426.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

z6 INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

the foreign economic impact on the Kiangnan economy reflected this

conjunction of Taiping destruction with strong foreign demand for silk.

By about 1870 mulberry trees had been replanted and production

recovered. But old silk-weaving centres were not fully reconstructed

because production was so strongly oriented to foreign trade. This trade

caused silk production to increase more rapidly than that of other

agricultural products, and mainly accounted for the area's rapid recovery

from the Taiping Rebellion and prosperity during the rest of the dynasty.

It restructured the raw silk industry, brought new areas into silk

production, and helped market town centres of silk collection recover

more rapidly than the large depopulated cities. Though efforts were made

to improve handicraft reeling so as to meet foreign demands for

uniformity, the major technical change came with steam filatures, mainly

in Shanghai. These became significant in the late 1890s, and thereafter

outstripped hand-reeled production. By 1911 filatures had secured peasant

specialization in cocoon production and a new set of brokers to move

cocoons quickly from farms to factories.

The silk trade helped the rise of new vigorous merchant-gentry families

and commercial organizations. How much peasant producers benefited

has not been determined. The record of silk in the Republican period was

to be much more ambiguous, but in the late nineteenth century it seems

that this foreign trade caused expansion of silk production, encouraged

modern industry, and had important socio-political ramifications within

elite society. The trade would have been still more profitable if Chinese

had been able to control export prices, and it would have survived better

in the long run if the government had made a concerted effort to improve

production methods, but for the time being it was the key to the prosperity

of Kiangnan.

Continuity after 1911

In the Republican era the substance of China's economic problems

remained essentially that of the late empire. First, a highly intensive,

traditional agricultural sector was barely able in 'normal' times to feed

an immense population. It was therefore usually incapable of providing

farm products for possible consumption by a large urban work-force, or

as raw materials for developing industry, or as exports to finance the

importation of critically needed capital and technology. Neither Yuan

Shih-k'ai nor the Peking mandarins who succeeded him, neither Sun

Yat-sen nor Chiang Kai-shek's Nanking and Chungking regimes,

certainly not the Japanese aggressors (except in Manchuria to a degree),

not even Mao Tse-tung in Kiangsi or Yenan - no one significantly affected

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GROWTH AND CHANGE IN THE ECONOMY 27

and improved the performance of China's agriculture in the first half of

the twentieth century.

Second, from the beginning of

the

third decade of the century the times

were rarely 'normal'. Civil wars and Japanese aggression and then civil

war again filled most of the next thirty years. The physical and especially

the human destruction inflicted upon China beggars any description. Yet

people survived, however scantily, and the economy before the very last

years of this grievous turmoil was not shattered. Indeed it showed a

remarkable resiliency during the infrequent periods of relative peace. This

we take as a sure sign of its low level of ' modern' development, of the

overwhelming persistence of traditional technology and localized

organization, not susceptible of being destroyed by invaders as a more

developed economy might have been.

Third, in much the same manner the modern sector of China's economy

was by far the less important in fact. Though China was much buffeted

by the world

—

the treaty powers and others

—

China's economy in the

first half of the twentieth century was still only very incompletely linked

to the world economy. The dualistic model of distinct treaty-port and

hinterland sectors may be too crude to describe the actual complexity of

Shanghai's economic role, or Canton's or Wuhan's. However, excessive

attention to bullion flows, to Maritime Customs statistical series, to the

terms of trade, or to foreign loans and investments can only be misleading.

There was simply no effective programme for the essential technical and

organizational (redistributive) changes in agriculture, without which no

genuine modern economic growth could ensue. Enlarged international

trade had fostered commercialized agriculture in some places during the

twentieth century. In parts of North China this process had in turn

enhanced economic and social differentiation in the villages, leading in

some circumstances to the ' semiproletarianization' of the poorer

peasants.

47

But this was neither a token that capitalist agriculture was

emerging in modern China nor is it much evidence of foreign economic

iniquities.

A fourth observation concerns the sometimes neglected power of

compound growth. The tiny modern industry initiated in the late

nineteenth century became a genuine and growing modern industrial

sector. The estimated rate of growth of these modern industrial enterprises

in the first five decades of the twentieth century was probably of the order

of 7 or 8 per cent per annum.

48

This annual rate is approximately what

47

Philip C.

C.

Huang,

The

peasant

economy

and social

change

in North China

is a

major study

of

changes

in the dominant small-peasant economy.

48

John

K.

Chang, Industrial development in pre-Commmist China:

a

quantitative analysis,

70-ioj.

And

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

28 INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

the People's Republic of China has achieved since 1949. Of course the

base from which this development began was infinitesimal at the start and

real annual increments to productive capacity were similarly tiny. But over

the decades, as growth was compounded, the structure of China's

economy began to change, at first slowly and then more rapidly, until

in the 1970s nearly 50 per cent of China's gross domestic product was

attributable to industry (factories and handicrafts), mining, utilities, and

transportation - not all ' modern' to be sure, but clearly differentiated

from agriculture, whose share had declined from perhaps two-thirds at

the beginning of the century to one-third in 1971.

Nevertheless, the Kuomintang

's

Nanking government and its predeces-

sors in Peking contributed little to this surprisingly vigorous, if still

sectorally and geographically limited, modern economic development.

Pre-modern growth - the increase of both total population and total

output but without sustained per capita increments - such as occurred in

the eighteenth century might not require a substantial state role; indeed

it probably benefited from its absence. But for a late effort to achieve

modern economic growth, larger political inputs are likely to be needed.

The Kuomintang government was not politically strong enough, or

sufficiently adaptable intellectually, to harness and develop the potential

of the private Chinese economy while at the same time ensuring an

acceptable minimum of personal and regional equality.

49

As a result, the small pre-1949 modern industrial sector, in the eighteen

province of China within the Great Wall and in Manchuria, provided the

PRC with managers, technicians, and skilled workers - the cadre that

could train the vastly expanded numbers who would staff the many new

factories that went into production in the 1950s. It was of course largely

unintended, but even if the foreign presence in China before 1949 had

sometimes inhibited independent development, its most efficacious legacy

appears to have been the initial transfer of technology that made possible

China's early industrialization.

Thus the Republic was more than a holding period in which the

economy everywhere remained stagnant while the political system disinte-

grated. On the contrary, aggregate growth in the modern urban sector

see Albert Feuerwerker,

'

Lun erh-shih shih-chi ch 'u-nien Chung-kuo she-hui wei-chi'

(On the

social crisis

in

early twentieth-century China),

in

Ts'ai Shang-ssu,

ed.

LJOI

Cb'ing-mo

Min-cb'u

Chung-kuo sbi-bui

(Chinese society

in the

late Ch'ing

and

early Republic), 129-33.

49

Susan Mann Jones, 'Misunderstanding

the

Chinese economy' skilfully reviews some

of

these

issues with references

to the

literature.

For a

revisionist Soviet view

of the

Kuomintang's

economic policies, which describes

a

combination

of

economic accomplishment

and

political

failure,

see A. V.

Meliksetov,

Sottial'no-ehmomicbesJkaia politika Gomin'dana

v

Kitae.

1)27—1949

(Kuomintang social-economic policy in China, 1927-1949). The relations of the Nationalist regime

to

the

Shanghai merchant community

are

examined

in

Joseph Fewsmith, Party, state, and

local

elite:

in

Republican

China.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHANGES IN SOCIAL STRUCTURE 29

prepared the way for further advances after 1949. At the same time,

however, most rural areas were not achieving the same growth

as

the cities.

Imbalances, instabilities, local disasters, warfare and at times inflation all

dragged down levels of production, inhibited commerce and discouraged

rural investment. Such troubles, though most shattering in the 1930s and

1940s, were present in varying degrees in different places throughout the

late Ch'ing and Republican

eras.

The social consequences were unsettling.

CHANGES IN SOCIAL STRUCTURE AND BEHAVIOUR

As a baseline from which to judge modern trends we posit first China's

high degree of socio-cultural homogeneity. The Han Chinese in different

regions and at different class levels had a common sense of identity and

historical continuity. Values were widely shared. Until recent times the

elite sought to maintain a rural base close to nature. In the villages a little

tradition did not set them sharply apart from a great tradition of the city

elite.

Instead the two strata shared a common folklore and cosmology,

including respect for ancestors, learning, property, and legitimized

authority.

Footbinding evidenced the cultural homogeneity under elite leadership.

The practice began at the T'ang court. It was backed by philosophers

of

the

Sung and pervaded the peasantry during the Ming and

Ch

'ing.

The

crippling of women's feet, that had begun as an upper-class male sexual

fetish and continued as an ostentatious display of urban affluence, spread

to the villages and seriously impaired the working capacity of half the

farming people. To ape their betters by such uneconomic mutilation of

females showed a high degree of peasant subservience to elite norms.

Similarly, village pantheons that integrated family stove gods, agricultural

spirits, and city deities into hierarchies reminiscent of the imperial

bureaucracy suggested a common acceptance of the authority structure

that the elite dominated.

Certain features of this homogeneous culture were slow to change - such

as respect for superiors and elders, sexual inequality, preservation of the

paternal line and equal inheritance among brothers. Local modifications

did not destroy such general practices even though the philosophical or

ideological expressions concerning them might change.

50

Although

50

Arthur

Wolf,'

Gods, ghosts and ancestors', in Arthur

Wolf,

ed. Keligim and ritual

in Chinese

society,

13

3—4j.

Stevan Harrell,

Ploughshare

village,

culture

and context in Taiwan, 9-15 discusses interaction

between general cultural principles, variations in customary behaviour expressing such principles,

and the socio-economic contexts (including such factors as class, geography, and technology)

in which such behaviour occurs. See also, Maurice Freedman, 'On the sociological study of

Chinese religion', in Arthur

Wolf,

ed. Religion, 19-42.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

3<D

INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

Confucianism was bitterly attacked in the twentieth century, its modes

of behaviour and underlying assumptions still persisted.

Horizontal and vertical

social

structures

The horizontal class structure

of

late imperial China

was

theoretically

divided

by

the Classics into the four occupational classes: scholar-gentry,

peasants, artisans,

and

merchants.

In

reality

it

more closely approached

a flexible two-tier structure:

a

small, educated, wealthy elite stratum

or

ruling class (about 5

per

cent

of

the population)

and the

vast majority,

who mainly

did

manual labour either

on the

land

or in the

cities. This

two-tier division left room

for

upward

and

downward mobility

and for

borderline positions bridging elite

and

non-elite status: such

as

poor

teachers

and

other underemployed lower-degree holders,

or

wealthy

peasants,

or

shop keepers. Dividing lines were flexible

and

there

was

considerable variation in criteria determining elite status. Military prowess

or leadership of local organizations including illegal groups might be more

important than education

in

determining elite status

in

some areas.

At the bottom were two strata below the respectable non-elite categories.

One was

a

permanently disadvantaged substratum

of

personal slaves and

mean people

who

were excluded from most respectable activities.

The

second consisted

of

drifters, beggars, bandits, smugglers,

and

others

operating outside the organizing structures

of

society. These were mainly

(but

not

entirely) drawn from

the

very poor,

but

like those

on the

borderline

of

elite status their social position was somewhat flexible,

for

if they

had not

severed kinship

or

local ties they might move back into

the lower levels

of

respectability. There

is no

good measurement

of

the

size

of

this diverse stratum,

but we

believe

it was

growing during

the

nineteenth

and

twentieth centuries, enlarged

by

disorders

and

natural

disasters. Moreover,

it had a

preponderance

of

males over females,

increased

by

waves

of

female infanticide that occurred during rebellions

or natural disasters.

This horizontal class structure, with

its

extreme differences

of

wealth,

was overlapped

by

vertical organizing principles based

on

kinship

and

locality. Especially

in

Central

and

South China, extended family lineages

were

a

major form

of

social organization. They enhanced the security and

continuity

of

elite families

and

provided services

and

opportunities

for

poorer lineage members. One's position in society might depend as much

upon what lineage one belonged to as on one's economic and occupational

status.

Between rich and poor, lineage ties were often stronger than class

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008