The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER

1

INTRODUCTION: PERSPECTIVES ON

MODERN CHINA'S HISTORY

Words are blunt and slippery tools for carving up and dissecting the past.

The history

of

modern China cannot

be

characterized

in a few

words,

however well chosen. The much used term ' revolution' is sometimes less

useful than 'revival', while

the

term 'modern transformation' signifies

little more than ' change through recent time' and leaves us still ignorant

of what 'time'

is. At a

less simplistic level, however, each

of the

twenty-eight authors writing in volumes 10 to 13 of

this

series has offered

generalizations about events and trends

in

China within the century and

a half from 1800

to

1949. Making more inclusive generalizations about

less inclusive ones

is no

doubt the historian's chief activity, yet most

of

the writers in these four volumes would accept the notion that the broader

a generalization is, the farther it is likely to be removed from the concrete

reality

of

events.

In

this view

the

postulating

of

all-inclusive processes

(such

as

progress

or

modernization)

or of

inevitable stages (such

as

feudalism, capitalism, and socialism) generally belongs to metahistory, the

realm

of

faith. While we need not deny such terms

to

those who enjoy

them, we can still identify them as matters

of

belief,

beyond reason.

1

At

a

less general level, however, social science concepts help

us to

explain historical events. Though history is not itself a social science,

its

task

is to

narrate past happenings

and to

synthesize

and

integrate

our

present-day understanding of

them.

For this purpose, metaphor has long

been a principal literary device of narrative history. Cities fall, wars come

to an end, hopes soar, but conditions ripen for an uprising and prospects

for progress grow gloomy

-

on and on, we describe social events largely

in metaphoric terms derived from the senses. Social scientists, too, having

to

use

words, write

of

structures, levels, downswings, acceleration

or

equilibria. Increasingly, however, mid-level concepts derived from social

science analyses are used

to

explain how events occurred, relating one

to

another. Chapter

1

of volume 12 suggested, for example, that the concept

of 'Maritime China',

as an

area

of

different ecology, economy, politics

1

For helpful comments

on

this chapter

we are

indebted

to

Marianne Bastid-Bruguiere, Paul

A. Cohen, Michael Gasster, Philip A. Kuhn and Ramon Myers, among others.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2 INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

and culture from 'Continental China', might be used to describe the

channels by which foreign influences came into Chinese society. In this

framework, the present chapter is concerned primarily with Continental

China. Moreover, since volumes 10, n and 12 dealt mainly with political,

economic and intellectual history, the present chapter seeks to take

account of recent work in the rapidly developing area of social history.

The reader will note at once that the customary attempt to treat' China'

as a unitary entity is becoming attenuated by the great diversity of

circumstances disclosed by closer study. The old notion of 'China's

cultural differentness' from the outside world, though it still strikes the

traveller, is becoming fragmented by the variety of sub-cultures to be

found within China.' Chinese culture' as an identifiable style of configura-

tion (created by the interplay of China's distinctive economy, polity, social

structure, thought and values) becomes less distinctive and identifiable

as modern international contact proceeds. As our knowledge grows,

generalization becomes harder, not easier.

Nevertheless we venture to begin at a high level of generality by

asserting that the Chinese revolution of the twentieth century has differed

from all other national revolutions in two respects - the greater size of

the population and the greater comprehensiveness of the changes it has

confronted. China's size has tended to slow down the revolution, while

its comprehensiveness has also tended to prolong it.

Consider first the flow of events: China underwent in the nineteenth

century a series of

rebellions

(White Lotus, 1796—1804; Taiping, 1850—64;

Nien, 1853-68; Muslim, 1855-73)

anc

^

a

series of

foreign

wars (British,

1839-42; Anglo-French, 1856-60; French, 1883-5, Japanese, 1894-5; and

the Boxer international war of 1900). There followed in the twentieth

century a series of

revolutions:

the Republican Revolution of 1911 that

ended the ancient monarchy, the Nationalist Revolution of 1923-8 that

established the Kuomintang party dictatorship, the Communist Revolu-

tion that set up the People's Republic in 1949, and Mao Tse-tung's

Cultural Revolution of 1966-76.

These milestones suggest that China's old order under the Ch'ing

dynasty of the Manchus was so strongly structured and so skilled in

self-maintenance that it could survive a century of popular rebellions and

foreign attacks. Yet its very strength undid it. It was so slow to adapt

itself to modern movements of industrialism and nationalism, science and

democracy, that it ensured its eventual demise.

Sheer size contributed to this slowness. Before the building of telegraph

lines in the 1880s, for instance, communication between Peking and the

provincial capitals at Foochow and Canton by the official horse post

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES 3

required at least a fortnight in each direction. The empire could not react

quickly. The imperialist wars of the nineteenth century were largely

decided by foreign naval power on the periphery of Chinese life. For

example, the 50 million people of Szechwan (now 100 million) were never

invaded even by the Japanese in 1937-45. China's '400 million' (now

i.ooo million) remained until recently unintegrated by widespread literacy,

a daily press, telecommunications or ease of travel by steamship, rail or

bus.

Change could come only slowly to peasant life on the land.

The comprehensiveness of change in modern China is a matter of

dispute between two schools of interpretation which posit linear and

cyclical patterns. The linear view stresses the influence of modern growth

not only in population and economy but especially in technology of

production, political nationalism and scientific thinking, which all con-

tribute to what some envision as ' modernization' and others are content

to call an overall revolution. The cyclical view sees

a

.repetition of phases:

decline of central power, civil war and foreign invasion, widespread

disruption and impoverishment, military revival of central power,

resumption of livelihood and growth. We incline to see these patterns

overlapping in various combinations. Innovation and revival are not

incompatible: modern China has borrowed from abroad but even more

from its own past.

From 1800 to 1949 China's cultural differentness strongly persisted even

though it was diminishing. Cocooned within the Chinese writing system

(which Japan, Korea and Vietnam broke out of by adding to it their own

phonetic systems), the bearers of China's great tradition preserved its

distinctive cultural identity as stubbornly and skilfully as the Ch'ing

dynasty preserved its power to rule. In fact, the symbiosis of China's

old state and culture was one secret of their longevity together.

If we look for

a

moment at the realm of thought and ideology, the tenets

of Confucianism had legitimized both imperial rule at Peking and family

patriarchy in the village. The dynastic monarchy collapsed only after

Confucianism had been disrupted by the tenets of evolution and Social

Darwinism.

2

The idea of the survival of

the

fittest among nations implied

that the Manchu rulers and indeed imperial Confucianism lacked the

capacity to lead the Chinese nation. It was as if the French Revolution,

instead of building upon ideas of the Enlightenment, had had to go

further back and begin by renouncing Plato, Aristotle and Descartes, as

well as the Virgin Mary. As one political scientist has remarked, 'Total

revolutions, such as the one in France that began in 1789 or the one that

2

Sec James Reeve Puscy, China and Charles Darwin; also The Cambridge history of China (CHOC)

12,

ch. 7 (Charlotte Furth).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

4 INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

has transformed China during this century, aim at supplanting the entire

structure of values and at recasting the entire division of labor. In France

between 1789 and 1797 the people employed violence to change the

systems of landholding, taxation, choice of occupation, education,

prestige

symbols,

military organization, and virtually every other character-

istic of the social system.

>3

For China, this statement might go even further. The comprehensiveness

of the Chinese revolution was evident in its reappraisal of the whole

Chinese past. The fact that modern science and technology, leading on

into industrialization and modern armament, came from abroad, in fact

from the imperialist West, put China's revolutionary generation in a

greater dilemma than European revolutionaries (to say nothing of

Americans) had ever faced. America's political leaders could quote British

authorities in support of their revolutionary actions. French revolu-

tionaries could find support in their own European heritage. For the

Chinese leadership of the early twentieth century, in contrast, the

intellectual authorities legitimizing their revolution were largely from

outside the country

—

and this in a land famous for being self-sufficient

in all things! A revolution in such terms, whether those of Rousseau,

Locke, Mill, Marx or Kropotkin, was subversive of the old China in the

most complete sense. While realizing the claims of nationalism, it

questioned the worth of China's historical achievements. These intellectual

demands of the revolution were hard for many patriots to accept. In fact,

the twin claims of science and democracy had implications too radical even

for many of Sun Yat-sen's generation. The displacement from tradition

was too great. This made it easier for patriots nostalgic for China's wealth

and power to speak of revival, putting their new wine in old bottles,

as has happened in the later phases of other revolutions.

Our historical thinking today about China's revolution is inevitably

multi-track, using analytic concepts from economics, sociology, anthropo-

logy, politics, literature and so on. We find useful many mid-level concepts

in the respective disciplines, but patterns of analysis that seem supportable

on one track may have no exact counterparts on other tracks. Incon-

sistencies may even appear among them. Since each line of analysis is

marked by phases, we begin with periodization.

CHANGE AND CONTINUITY: PERIODIZATION

Despite much continuity, China from 1800 to 1949 underwent tremendous

changes. The political system, especially the relationship between state

' Chalmers Johnson, Revolutionary

change,

2nd ed., 126.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHANGE

AND

CONTINUITY

HEILUNGKIANG

£ K

I

R

I

N

/

•»"

Tstngtao

KiaochcwBay

IANGSU

Yangchow

nkiang

•,

/ Ningpo'

TChingite-

chen

V

CHEKIA

anchang

V

KIA'NGSI

'

/

'

WANGSI

Wuchow".

r-KWANGTUNG

Waichow

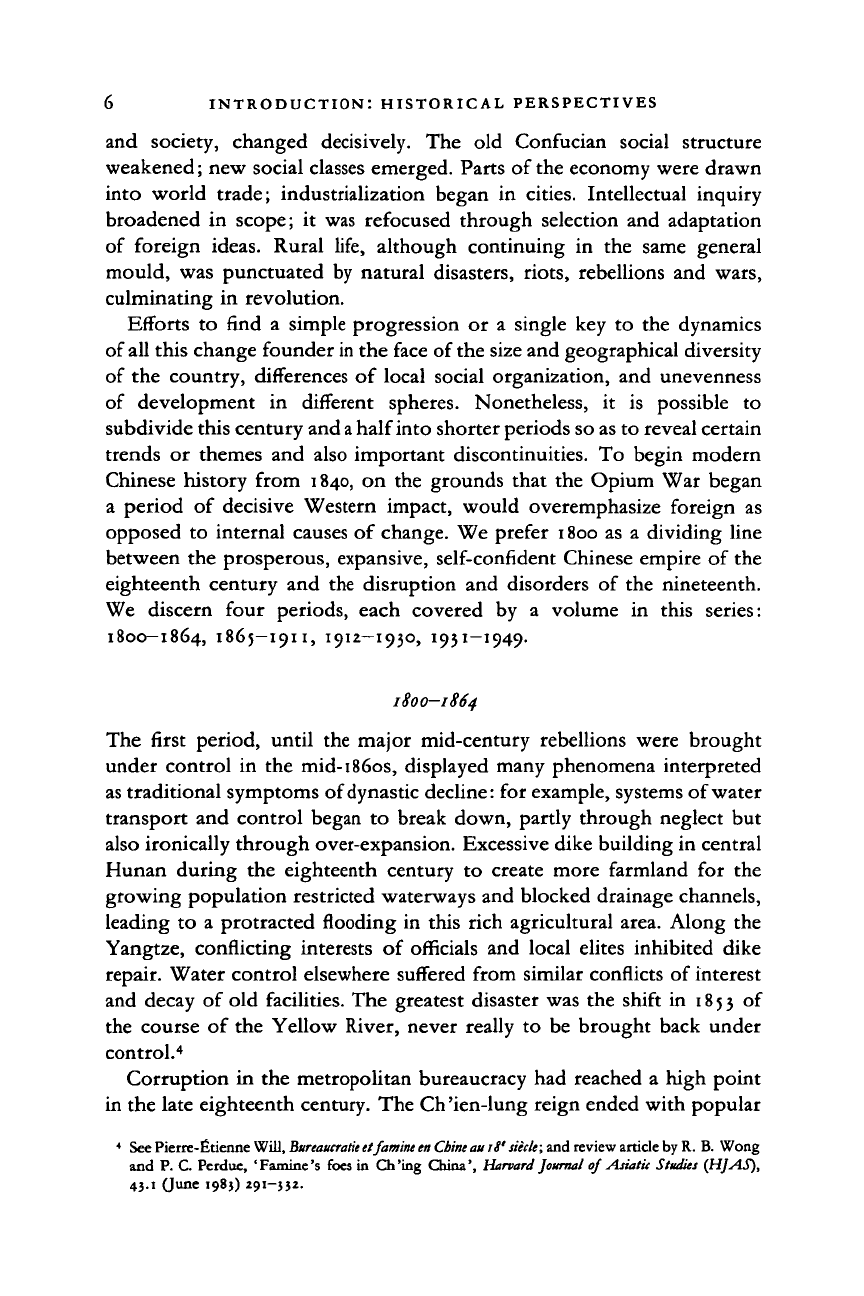

Provinces of China under the Republic

—— Province boundaries

o Province capitals

• Other cities

A

Famous mountains

0 59O 1 1 1

1

I

6^

' ' ' '

ibo mile

MAP

2.

Provinces

of

China under

the

Republic

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

6 INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

and society, changed decisively.

The old

Confucian social structure

weakened;

new

social classes emerged. Parts

of

the economy were drawn

into world trade; industrialization began

in

cities. Intellectual inquiry

broadened

in

scope;

it was

refocused through selection

and

adaptation

of foreign ideas. Rural life, although continuing

in the

same general

mould,

was

punctuated

by

natural disasters, riots, rebellions

and

wars,

culminating

in

revolution.

Efforts

to

find

a

simple progression

or a

single

key to the

dynamics

of

all

this change founder in

the

face

of

the size

and

geographical diversity

of

the

country, differences

of

local social organization,

and

unevenness

of development

in

different spheres. Nonetheless,

it is

possible

to

subdivide this century and

a

half into shorter periods so as

to

reveal certain

trends

or

themes

and

also important discontinuities.

To

begin modern

Chinese history from 1840,

on the

grounds that

the

Opium

War

began

a period

of

decisive Western impact, would overemphasize foreign

as

opposed

to

internal causes

of

change.

We

prefer

1800 as a

dividing line

between

the

prosperous, expansive, self-confident Chinese empire

of the

eighteenth century

and the

disruption

and

disorders

of the

nineteenth.

We discern four periods, each covered

by a

volume

in

this series:

1800—1864, 1865—1911, 1912—1930, 1931—1949.

1800-1864

The first period, until

the

major mid-century rebellions were brought

under control

in the

mid-1860s, displayed many phenomena interpreted

as traditional symptoms of dynastic decline:

for

example, systems of water

transport

and

control began

to

break down, partly through neglect

but

also ironically through over-expansion. Excessive dike building

in

central

Hunan during

the

eighteenth century

to

create more farmland

for the

growing population restricted waterways

and

blocked drainage channels,

leading

to a

protracted flooding

in

this rich agricultural area. Along

the

Yangtze, conflicting interests

of

officials

and

local elites inhibited dike

repair. Water control elsewhere suffered from similar conflicts

of

interest

and decay

of old

facilities.

The

greatest disaster

was the

shift

in 1853 of

the course

of the

Yellow River, never really

to be

brought back under

control.

4

Corruption

in the

metropolitan bureaucracy

had

reached

a

high point

in

the

late eighteenth century.

The

Ch 'ien-lung reign ended with popular

4

See Pierre-Iitienne

Will,

Bureaucratit

et

famine

en Chine

au

iS'

sie'cle;

and review article by R.

B.

Wong

and

P. C.

Perdue, 'Famine's foes

in

Ch'ing China',

Harvard

Journal

of

Asiatic

Studies

(HJAS),

43.1

(June 1983)

291-332.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHANGE AND CONTINUITY 7

unrest: riots, protests against taxes and rent, and rebellions inspired by

both heterodox millenarian sects and socio-economic dislocation. Invasion

of the imperial palace during an otherwise minor sectarian rising in 1813

shocked the court and metropolitan officials.

s

By the late 1850s rebellions

were seriously threatening to bring down the dynasty. Minority peoples

on the borders took advantage of disorder in the central provinces to

launch their own rebellions.

6

Pirates operated along the coast, and

Western nations began to attack the seaboard cities and exact political and

economic concessions.

In the face of these problems the government appeared weak. Its armies

were unable to suppress rebels, its taxes inadequate to pay the cost of doing

so.

Difficulties in grain transport along the Grand Canal threatened

Peking's food supply. The nineteenth-century emperors appeared timid

and incompetent in comparison with their brilliant and forceful predeces-

sors.

Official corruption and negligence seemed widespread. Suppression

of the major rebellions by newly organized, regionally based armies

suggested a decentralization of power was under way, while deflation

contributed to governmental fiscal problems and more general economic

retrenchment.

However, the traditional downswing of the dynastic cycle did not cover

two major aspects of this period. First, the population grew to truly

unprecedented

levels.

Whereas there were

200—250

million people in China

in 1750, there were 410—430 million in 1850.

7

The economic, social,

political, and administrative repercussions of this growth could not be

simply cyclical in character. Second, the imperialist West, powered by the

industrial technology and economic expansiveness of Western capitalism,

posed a more fundamental challenge than China's previous nomadic

invaders. These two factors alone meant that changes would transcend

cyclical patterns. The wave of rebellions threatening the old order in the

mid-nineteenth century failed. Reorganized government armies with

superior fire power would limit the scope of popular upheaval for the

rest of the century. Impetus for change was not thereby cut off, but

reappeared in other channels.

186J-1911

In the second period growth and innovation became more prominent than

decline and decay. The latter did not, of course, disappear. For example,

5

Susan Naquin,

Millenarian rebellion

in

China:

the

Eight

Trigrami uprising

of iSij.

6

See S. M. Jones and P. A. Kuhn, 'Dynastic decline and the toots of rebellion', CHOC to,

especially 152-44.

7

Dwight Perkins,

Agricultural development in China

ijfS-fffy, 207-14.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

8 INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

famines were caused

by

floods

on the

North China plain

in the

late 1870s

and

in the

Yangtze

and

Huai River valleys

in the

1900s. Rural unrest,

which

had

diminished after

the end of the

mid-century rebellions,

increased again after 1890, along with

the

growth

of

anti-dynastic secret

societies.

Such manifestations

of

decline were, however, accompanied

by new

developments that would continue into

the

twentieth century.

The

startling military threat

of

imperialism roused

an

effort

at

self-defence

through Western-style industralization

and

modern army building.

New

types

of

official-entrepreneurs

and

educated army officers emerged.

Foreign trade

and

industry

in

treaty ports produced compradors,

merchant-capitalists, professional people

and

factory workers. While these

new urban social classes were coming into being,

a

genuine public

opinion, roused

by

patriotism

and

spread through

the

treaty-port press,

became

a

political factor

in the

1880s. Activist political organization

among

the

scholar elite began

in the

reform movement

of the

1890s.

Various elite elements then clashed with

and

became alienated from

the

existing political authority. Some turned

to

foreign examples

and

ideas

for ways both

to

strengthen the country and

to

further political

or

personal

goals.

The

result

was a

vast expansion

in the

range

and

nature

of

intellectual inquiry, which brought into question

the

fundamental tenets

of

the

Confucian world view

and

social order.

8

Major rebellions

of the

mid-nineteenth century

had

originated

in

peripheral

or

impoverished areas:

the

Kwangsi hills populated

by

Hakka,

the flood-plagued plains

of

Huai-pei,

the

homelands

of the

Miao tribes

in south-west China and the Muslim areas of the south-west and north-west.

In

the

late nineteenth

and

early twentieth centuries, however, major

political activity arose

in the

wealthy economic cores:

the

Canton delta,

the urbanized Lower Yangtze, the middle Yangtze with its rich agricultural

lands

and

emerging industrial centres.

The

major actors,

too, now

included

the new

social groups within

the

fragmented elite.

During

the

last decade

of the

Ch'ing,

the

competition between

bureaucratic leaders of the central government and

a

variety of provincially

based social elites attained

a new

height

in

Chinese politics. Reform

and

change were

in the air,

accepted

on

both sides.

The

issue

was

whether

the

new and

greater political

and

economic potential

of the

state should

continue, like

the old, to be

centralized

in the

bureaucratic monarchy,

or

should

be

diffused

so

that policies could reflect initiatives

of

elite groups

outside

the

government. This question forecast

a

significant shift

in the

relationship of the state

to

the society.

It

ensured that

the

1911 Revolution

would

not be

just another dynastic change.

8

See M.

Bastid-Bruguiere, 'Currents

of

social change', CHOC

11.535-602.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHANGE AND CONTINUITY

Many claim that the 1911 Revolution did little to alter rural social

relationships; some even question whether it was a revolution at

all.

There

were indeed many continuities running through 1911. Industrial growth

continued in urban centres

—

for example, around Tientsin and in

southern Manchuria as well as in the mid- and Lower Yangtze and the

southern coast. Despite the disintegration of central power and military

competition between warlords, some provinces like Chekiang were

relatively stable and free of war. Even in places like Kwangsi, where there

was considerable fighting, it often avoided disrupting the agricultural

schedule. Political activity and organization remained centred in the cities.

As the new trends continued, however, differences in degree became

differences in kind. The modern economic sector developed more rapidly

than the rural sector. The new social classes, aided by the emancipation

of youth and women, continued to reshape the old social structure.

Meanwhile vernacular literature and the popular press, intellectual debate

and the idea of mass mobilization, became increasingly significant. The

disappearance of the emperor and the old political structure changed the

sources of legitimacy and profoundly altered the nature of politics. Han

Chinese nationalism, an overt concern for China, replaced loyalty to an

imperial dynasty.

Second, in the absence of the imperial institution, military power

became a more important political factor than it had been since the end

of the Taiping Rebellion, and operated with a freedom from civil control

impossible under the Ch'ing. But since military power was too fragmented

to win control of the country, a third major change of this period was

the effort by out-of-power urban elites to mobilize the lower '" sses in

politics. This extension of participation was attempted by new, more-

than-factional party organizations that tried to encourage and control such

mobilization. It was accompanied by new political ideologies of Marxism-

Leninism and Sun Yat-sen

's

Three People's Principles.

The goals of revolution and the nature of radicalism changed. The 1911

Revolution had been largely an elite rebellion against the centralized

bureaucratic monarchy. Political radicalism began by espousing national-

istic and racial themes against the Ch'ing political structure. A social

radicalism also arose against the authoritarian Confucian familial bonds.

This strain culminated in the individualism, demands for further liberation

of youth and women, and enthusiasm for science and democracy of the

New Culture movement. Subsequently during the May Fourth movement

radicalism was redefined in class terms to further the needs of workers

and peasants against warlords, capitalists and landlords. Revolution now

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

io

INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

meant both national liberation from 'imperialism'

and

class struggle

against

'

feudalism'

-

goals which radicals sought

to

combine, while

conservatives sought

to

keep them apart.

In

the

mid-1920s

the

revolution expanded

by

combining military

and

party organization with anti-imperialist patriotism

and a

mobilization

of

workers

and

peasants under

the

leadership

of

urban intellectuals.

The

Communist-Nationalist alliance

and

Northern Expedition were logical

culminations

of

this period.

The

break

in

1927

between

the

Chinese

Communist Party (CCP) plus their left-wing Kuomintang

(KMT)

allies

and

the

right-wing

of the KMT

revealed

the

contradiction

in

aims that

had been temporarily obscured

by

shared nationalism

and

opposition

to

warlords. Establishment

of the

Nanking government, controlling

at the

outset only about

two

provinces, left undecided

the

question whether

changes would

be

brought about

by a

new bureaucratic modernizing state

or

by

continued efforts

to

mobilize broader participation

on a

more

egalitarian

and

less centralized basis.

9

Three events

at

the

beginning

of

the

1930s decade profoundly affected

the course

of

Chinese history. First,

in

1931

the

world economic

depression

hit

China. Abandonment

of the

gold standard

by

Britain

and

Japan forced

a

dramatic devaluation

of

the Chinese silver-based currency,

while

US

government purchases drained silver from China. Foreign

markets

for

silk

and

other exports collapsed,

and

Japanese dumping

damaged

the

staggering cotton textile industry. Agricultural prices

in

commercialized core areas dropped faster than prices generally,

to

about

half their 1929-31 levels, hurting both farmers

and

landlords.

10

Capital

was scarce, interest rates were

up,

urban workers unemployed, govern-

ments

had

problems collecting revenues. Severe floods

in

the

Yangtze

basin

in

1931 and an

equally disastrous drought

in 1934

made matters

worse

for the

Nationalists. Despite some evidence

of

recovery

in 1936,

economic improvement

was

forestalled

by the

Japanese attack.

In

the

1940s run-away inflation wrecked

the

livelihood

of

the

urban middle

classes,

and

played havoc with Nationalist government finances. Rural

areas tended

to

economic autarky.

Second,

the

Japanese seized Mukden

in

September 1931, conquered

Manchuria, established

a

puppet government, took control

of

Hopei

and

5

See

C.

M.

Wilbur,

"The

Nationalist Revolution: from Canton

to

Nanking,

1923-28',

CHOC

12.527-720.

'•

See

CHOC

12.71-2.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008