The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHINGGIS KHAN AND THE EARLY MONGOLIAN STATE 351

afford to concentrate his forces against the Chin, his most powerful neigh-

bor.

39

The Mongolian formations departed from the Keriilen early in the year

and by spring reached the Onggiid territory, which they used as a staging

area for their forthcoming invasion. The center and left, that is, eastern,

wing of their army, led by Chinggis khan, assaulted and captured many

fortifications along the Chin's northern frontier, including Chii-yung kuan, a

pivotal garrison guarding the approaches to its capital, Chung-tu (modern

Peking). The Jurchen court dispatched sizable reinforcements to their endan-

gered borders, but these contingents were defeated piecemeal as they moved

to the north. The Chin defenses were so disorganized by these setbacks that

elements of the Mongolian army were able to reach and pillage the environs

of Chung-tu. In the meantime, the right, that is, western, wing of the

Mongolian army under Chinggis khan's sons advanced into Shansi, taking a

few cities, ravaging the countryside, and, most important, tying down en-

emy troops. When the order to withdraw came in the beginning of 1212,

both wings of the Mongolian army returned to the north, abandoning most,

if not all, of the Chin territories that they had occupied. By all available

indications, the campaign of 1211 had as its immediate goal booty and

information, not the acquisition of territory.

40

The Chin forces quickly reoccupied their northern frontier regions and

prepared for the next onslaught. In the fall of 1212 the Mongols returned and

began pressuring the.Jurchens' outer defenses. Key garrisons such as Chii-

yung kuan had to be reduced a second time, and this was achieved in 1213

only after Chinggis khan committed additional forces to the task. Once the

frontier defenses were pierced, the Mongols struck rapidly south, penetrating

much deeper into Chin territory than they had done previously. When they

reached the agricultural areas north of the Yellow River, the army divided

into three groups that spread devastation throughout Shantung, Hopei, and

shansi. Some cities were taken and looted, but in general the Mongols

concentrated their attention on the open countryside, bypassing strong

points whenever possible.

In late 1213 the Mongolian armies, having wreaked great destruction in

the Chin heartland, began moving back to the north. This time, however,

they retained control of all major frontier passes and left a force around

Chung-tu to enforce a close blockade. Efforts to invest the city proved

unsuccessful, but the alarmed Chin emperor was induced to negotiate. He

offered the Mongols much tribute

—

gold, silk, and horses

—

in return for an

39 On the campaigns against the Chin, see Henry D. Martin, The rise o/Chingis khan and hii

conquest

of

North China (Baltimore, 1950; repr. New York, I97i),pp. 113-219.

40

Secret

history,

sec. 248 (pp. 184—5); and Sechenjagchid, "Patterns of trade and conflict between China

and the nomads of Mongolia,"

Zentralasiatische

Studien,

11 (1977), p. 198.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

352 THE RISE OF THE MONGOLIAN EMPIRE

end

of

hostilities. They accepted these terms and, as agreed, discontinued

their blockade

in

the spring

of

1214. The Jurchen court, unnerved by the

experience, used this respite to depart from Chung-tu for K'ai-feng, which

they established as their new capital in the summer of 1214.

When the departure of the ruling house became known to Chinggis khan

later in the fall, he immediately ordered his forces back to the recently besieged

city. All attempts

to

take Chung-tu by storm failed, owing

to

the dogged

resistance of its garrison. Finally Chinggis khan arrived on the scene in January

1215 and took direct control of the operations. When it became apparent that

the Mongols had turned aside Chin relief

armies,

the garrison's morale gave

way, and the city surrendered to the attacking forces at the end of May. In the

weeks following

its

capitulation, the capital was systematically sacked and

partially destroyed by fire. His immediate military goal accomplished and the

vast booty properly inventoried, Chinggis khan left Chung-tu for Mongolia,

leaving behind garrisons in the captured Chin territories.

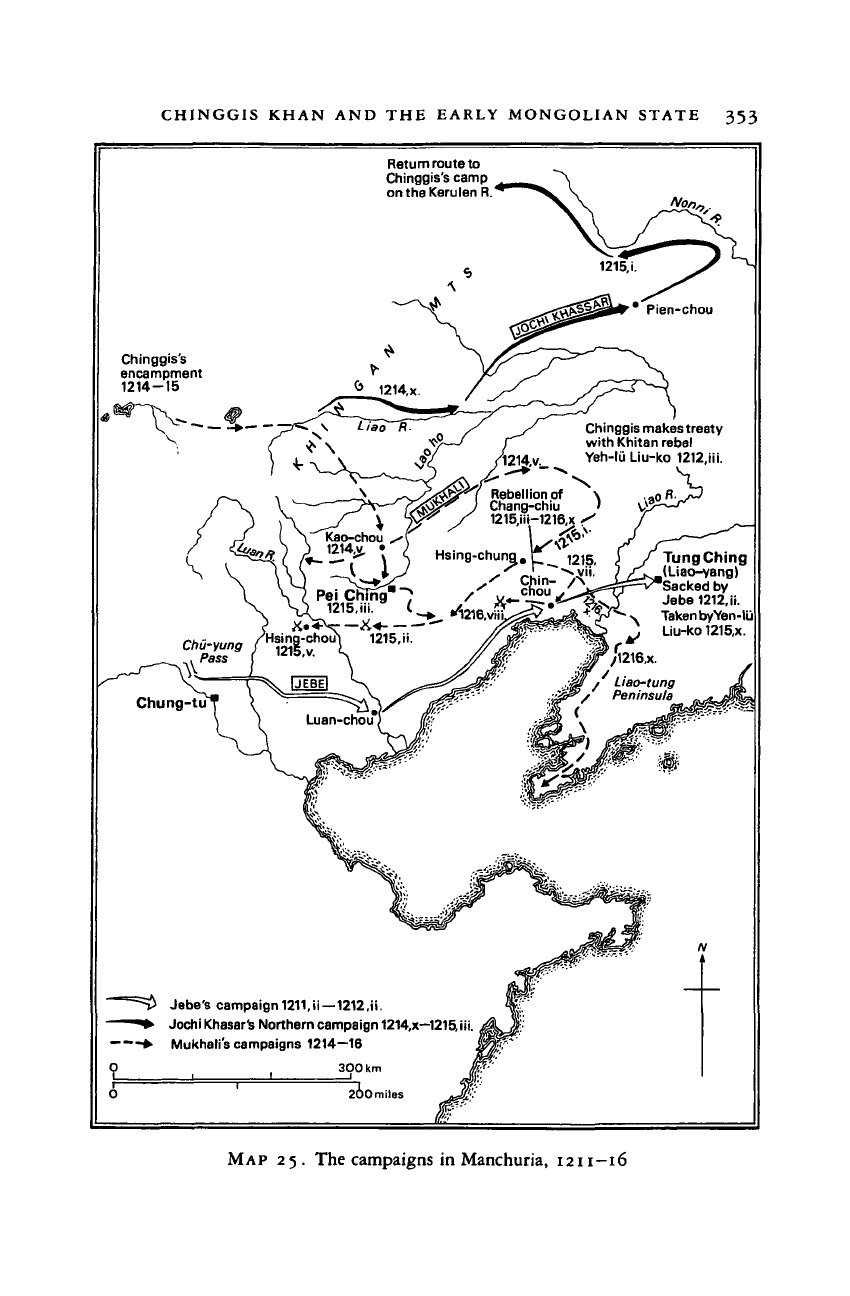

The loss of its capital was not, however, the only serious setback suffered

by the Chin at this time. In 1212 the Mongolian general Jebe penetrated the

Liao River valley and toward the end of the year temporarily seized Tung-

ching (modern Liao-yang), the eastern capital of

the

Jurchen.

The occupation

of this city,

a

major defeat

in

itself,

helped,

in

turn, ignite

a

widespread

rebellion among the Khitan (Ch'i-tan), another Manchurian-based people,

who had been unwilling subjects

of

the Chin since the fall

of

their own

dynasty, the Liao,

in

1115. Taking full advantage of the growing discomfi-

ture

of

their opponents, Mongolian armies

in

1214 successfully attacked

Chin positions east and west of the Liao River. Tung-ching was again occu-

pied

in

1215 and subsequently became the main base for the Khitan rebel

leader, Yeh-lii Liu-ko, who now formally acknowledged Mongolian suzer-

ainty.

41

By the following year a large part of Manchuria, the Jurchen home-

Land, was in enemy hands (see Map 25). A concentrated Mongolian assault at

this juncture might well have brought the Chin dynasty

to

the point

of

collapse, but events unfolding in Turkestan would soon cause Chinggis khan

to direct the bulk

of

the Mongols' military efforts westward

for

nearly

a

decade.

Campaign in the

west

Mongolian involvement in the Western Regions, the Hsi-yii of the Chinese,

began in 1208 when a punitive expedition was mounted against a coalition of

41 On Khitan uprisings against the Chin, see Sechen Jagchid, "Kitan struggles against Jurchen oppres-

sion: Nomadism versus sinicization,"

Zentralasiatische

Studim,

16 (1982), pp. 163-83.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHINGGIS KHAN AND THE EARLY MONGOLIAN STATE 353

Return route to

Chinggis's camp

ontheKerulenR."

Chinggis's

encampment

1214-15

Chinggis makes treaty

with Khitan rebel

Yeh-lii Liu-ko 1212,iii.

Rebellion of

Chang-chiu

n V

chung.

£

1215

,

TungChing

(Liao-yang)

eked by

Jebe 1212,ii.

•v

Taken

byYen-lu

X.*V—

A«

4

#^/

Peninsula

Jebe's campaign 1211,ii—1212.U.

Jochi Khasar's Northern campaign

1214,x—1215,

iii.

Mukhalis campaigns 1214—16

300 km

MAP

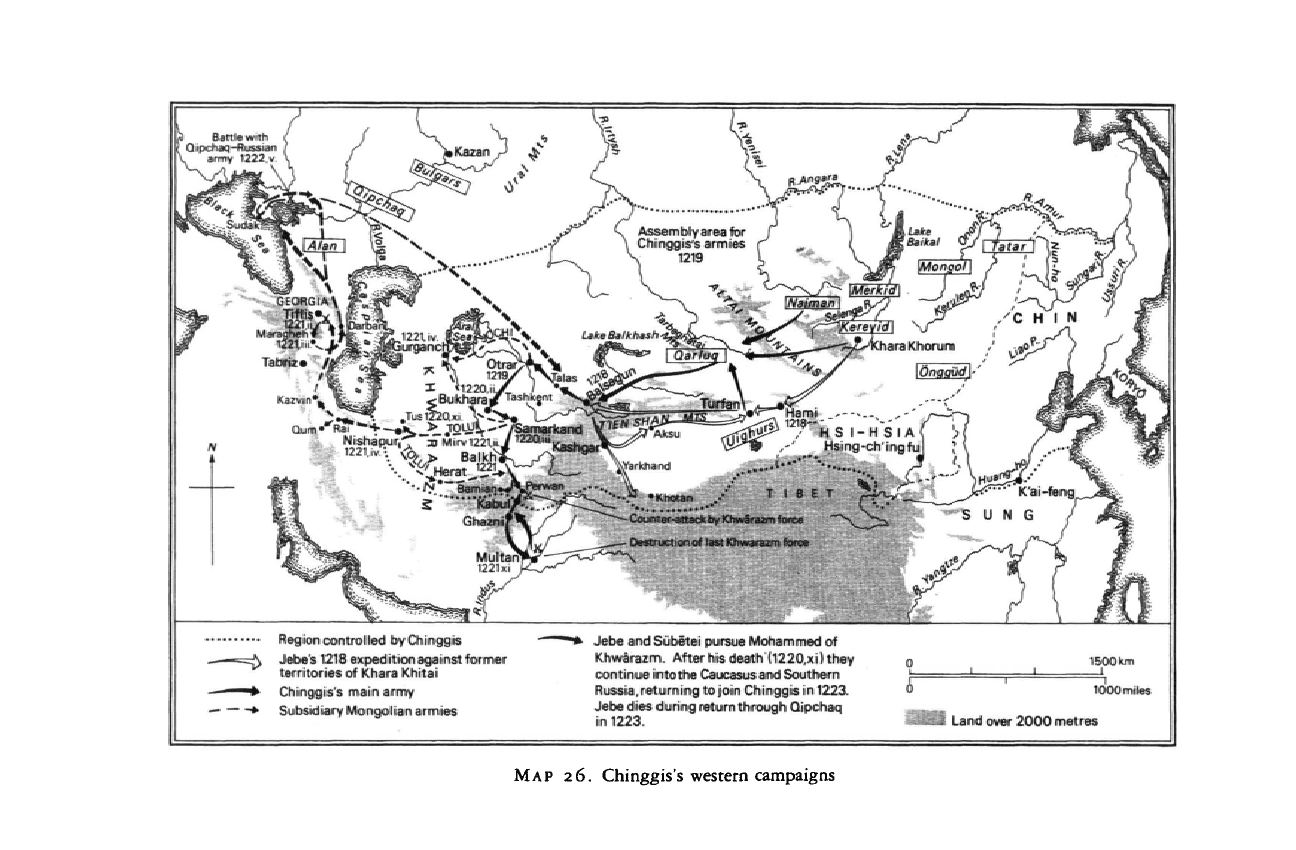

25. The campaigns in Manchuria, 1211—16

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

354

THE

RISE OF THE MONGOLIAN EMPIRE

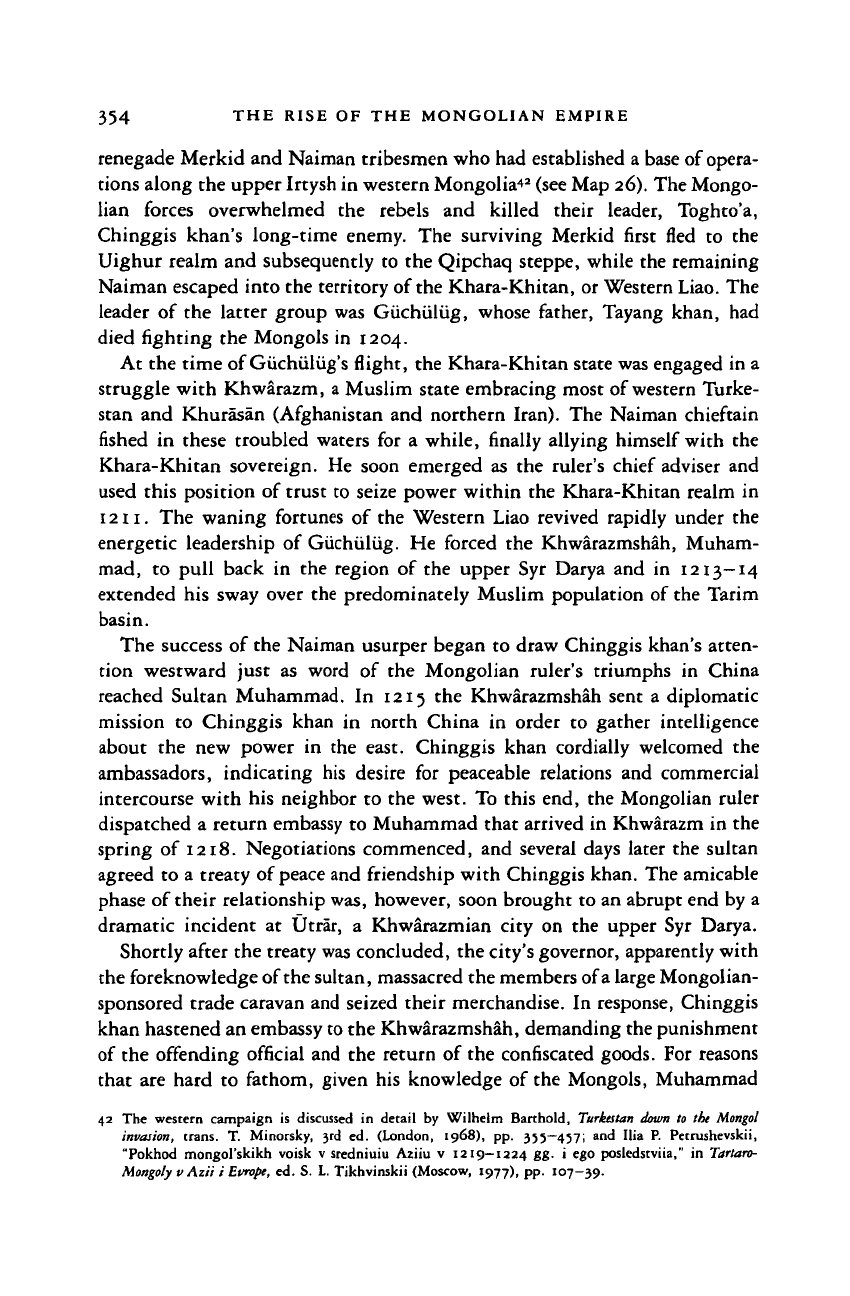

renegade Merkid and Naiman tribesmen who had established a base of opera-

tions along the upper Irtysh in western Mongolia^

2

(see Map 26). The Mongo-

lian forces overwhelmed the rebels and killed their leader, Toghto'a,

Chinggis khan's long-time enemy. The surviving Merkid first fled to the

Uighur realm and subsequently to the Qipchaq steppe, while the remaining

Naiman escaped into the territory of

the

Khara-Khitan, or Western

Liao.

The

leader of the latter group was Giichuliig, whose father, Tayang khan, had

died fighting the Mongols in 1204.

At the time of Giichiiliig's flight, the Khara-Khitan state was engaged in a

struggle with Khwarazm, a Muslim state embracing most of western Turke-

stan and Khurasan (Afghanistan and northern Iran). The Naiman chieftain

fished in these troubled waters for a while, finally allying himself with the

Khara-Khitan sovereign. He soon emerged as the ruler's chief adviser and

used this position of trust to seize power within the Khara-Khitan realm in

1211.

The waning fortunes of the Western Liao revived rapidly under the

energetic leadership of Giichuliig. He forced the Khwarazmshah, Muham-

mad, to pull back in the region of the upper Syr Darya and in 1213—14

extended his sway over the predominately Muslim population of the Tarim

basin.

The success of the Naiman usurper began to draw Chinggis khan's atten-

tion westward just as word of the Mongolian ruler's triumphs in China

reached Sultan Muhammad. In 1215 the Khwarazmshah sent a diplomatic

mission to Chinggis khan in north China in order to gather intelligence

about the new power in the east. Chinggis khan cordially welcomed the

ambassadors, indicating his desire for peaceable relations and commercial

intercourse with his neighbor to the west. To this end, the Mongolian ruler

dispatched a return embassy to Muhammad that arrived in Khwarazm in the

spring of 1218. Negotiations commenced, and several days later the sultan

agreed to a treaty of

peace

and friendship with Chinggis khan. The amicable

phase of their relationship was, however, soon brought to an abrupt end by a

dramatic incident at Utrar, a Khwarazmian city on the upper Syr Darya.

Shortly after the treaty was concluded, the city's governor, apparently with

the foreknowledge of the sultan, massacred the members of a large Mongolian-

sponsored trade caravan and seized their merchandise. In response, Chinggis

khan hastened an embassy to the Khwarazmshah, demanding the punishment

of the offending official and the return of the confiscated goods. For reasons

that are hard to fathom, given his knowledge of the Mongols, Muhammad

42 The western campaign is discussed in detail by Wilhelm Bart hold, Turkestan down to the Mongol

invasion, trans. T. Minorsky, 3rd ed. (London, 1968), pp. 355—457; and Ilia P. Petrushevskii,

"Pokhod mongol'skikh voisk v sredniuiu Aziiu v 1219—1224 gg. i ego posledstviia," in Tarlaro-

Moagoly v Azii i Etmpe, ed. S. L. Tikhvinskii (Moscow, 1977), pp. 107-39.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Assembly

area for

Chinggis's armies

*?;

x

'•'•ft'*^Bemian»J\EBrwan ..- .. \, / ,

Region

controlled

by

Chinggis

Jebe's 1218 expedition

against

former

territories of Khara Khitai

Jebe andSiibetei pursue Mohammed of

Khwarazm. After

his

death (1220,xi) they

continue into the

Caucasus and

Southern

Russia,

returning to join

Chinggis in 1223.

Jebe dies during

return

through Qipchaq

in

1223.

Chinggis's main army

Subsidiary Mongolian armies

MAP

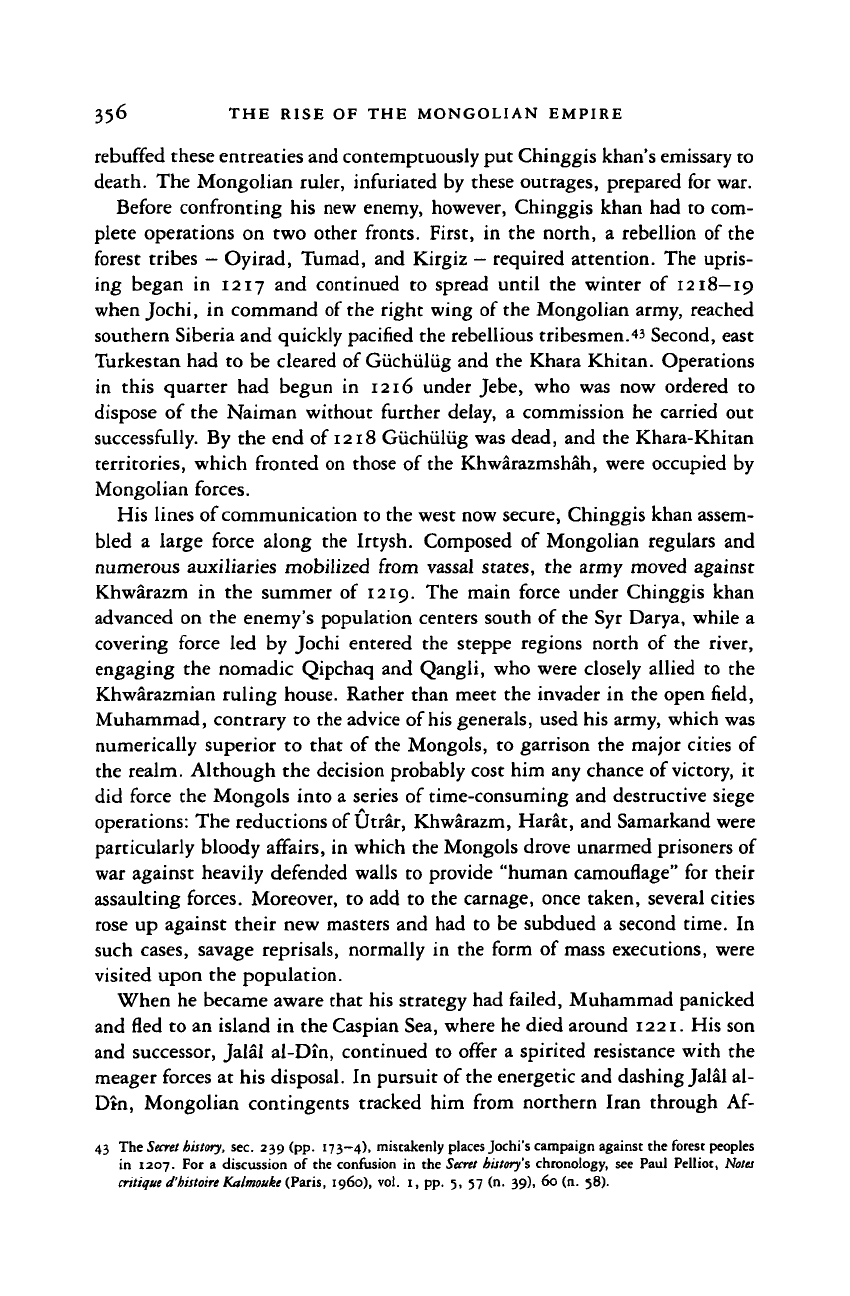

26. Chinggis's western campaigns

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

356 THE RISE OF THE MONGOLIAN EMPIRE

rebuffed these entreaties and contemptuously put Chinggis khan's emissary to

death. The Mongolian ruler, infuriated by these outrages, prepared for war.

Before confronting his new enemy, however, Chinggis khan had to com-

plete operations on two other fronts. First,

in

the north,

a

rebellion of the

forest tribes

-

Oyirad, Tumad, and Kirgiz

-

required attention. The upris-

ing began

in

1217 and continued

to

spread until the winter

of

1218—19

when Jochi,

in

command of the right wing of the Mongolian army, reached

southern Siberia and quickly pacified the rebellious tribesmen.« Second, east

Turkestan had to be cleared of Giichiilug and the Khara Khitan. Operations

in this quarter had begun

in

1216 under Jebe, who was now ordered

to

dispose of the Naiman without further delay,

a

commission he carried out

successfully. By the end of 1218 Giichiilug was dead, and the Khara-Khitan

territories, which fronted on those of the Khwarazmshah, were occupied by

Mongolian forces.

His lines of communication to the west now secure, Chinggis khan assem-

bled

a

large force along the Irtysh. Composed

of

Mongolian regulars and

numerous auxiliaries mobilized from vassal states, the army moved against

Khwarazm

in

the summer

of

1219. The main force under Chinggis khan

advanced on the enemy's population centers south of the Syr Darya, while a

covering force

led

by Jochi entered the steppe regions north

of

the river,

engaging the nomadic Qipchaq and Qangli, who were closely allied

to

the

Khwarazmian ruling house. Rather than meet the invader in the open field,

Muhammad, contrary to the advice of

his

generals, used his army, which was

numerically superior

to

that of the Mongols, to garrison the major cities of

the realm. Although the decision probably cost him any chance of

victory,

it

did force the Mongols into a series of time-consuming and destructive siege

operations: The reductions of Utrar, Khwarazm, Harat, and Samarkand were

particularly bloody affairs, in which the Mongols drove unarmed prisoners of

war against heavily defended walls to provide "human camouflage" for their

assaulting forces. Moreover, to add to the carnage, once taken, several cities

rose up against their new masters and had to be subdued

a

second time.

In

such cases, savage reprisals, normally

in

the form of mass executions, were

visited upon the population.

When he became aware that his strategy had failed, Muhammad panicked

and fled to an island in the Caspian Sea, where he died around 1221. His son

and successor, Jalal al-Din, continued to offer

a

spirited resistance with the

meager forces at his disposal. In pursuit of

the

energetic and dashing Jalal al-

Din, Mongolian contingents tracked him from northern Iran through

Af-

43 The

Secret

history,

sec. 239 (pp. 173-4), mistakenly places Jochi's campaign against the forest peoples

in 1207. For

a

discussion

of

the confusion

in

the

Secret history's

chronology, see Paul Pelliot,

Notes

critique

d'histoire

Kalmouke

(Paris, i960), vol. 1, pp.

5,

57 (n. 39), 60 (n. 58).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHINGGIS KHAN AND THE EARLY MONGOLIAN STATE 357

ghanistan into India and then back to Iran and Azerbaijan. To the Mongols'

frustration he always managed to elude capture, but heroics of this nature

could not long forestall the collapse of the Khwarazmian state. By 1223

Turkistan and Khurasan had been subjugated and Mongolian garrisons and

governors

(darughachi)

installed in all urban centers. Despite the hopelessness

of his cause, Jalal al-Din refused to capitulate and continued his futile defi-

ance until his death at the hands of Kurdish bandits in 1231.

With organized resistance coming to an end in the Khwarazmian realm,

the Mongols began preparations for their next series of conquests. Siibetei

and Jebe, who were campaigning in Georgia and Azerbaijan at this time,

asked permission to cross the Caucasus and attack the Qipchaqs. Chinggis

khan readily consented, and in 1221 Siibetei commenced his famous raid, or,

more accurately, reconnaissance in force, into western Eurasia. Accompanied

by an army of three

ttimen,

he moved into the south Russian steppe and in the

late spring of 1223 defeated the combined forces of the Russian princes and

western Qipchaqs at the battle of the Kalka River (a small stream flowing

into the Sea of Azov). Siibetei next scouted the Russian principalities as far

west as the Dnieper and then turned back east, fighting a brief engagement

with the Volga Bulghars before returning to western Mongolia in 1224. The

necessary intelligence having been gathered, Jochi was ordered to launch a

follow-up campaign to bring the western steppe under Mongolian dominion.

Chinggis khan in the meantime had withdrawn the bulk of his armies

from Turkestan, reaching the Irtysh in the summer of 1224 and central

Mongolia in the spring of 1225. Back at home, he planned yet another

campaign: In 1223 the Tangut ruler had without warning withdrawn his

forces, which had been supporting Mongolian operations against the Chin,

and the Mongolian leader was determined to exact a heavy penalty for this

faithlessness.

Mukhali's

campaigns

against the Chin

When Chinggis khan reached the Keriilen in late 1215 or early 1216,

Mongolian operations against the Chin were scaled down temporarily but not

halted. Mukhali, one of Chinggis khan's most able and trusted generals,

continued his efforts to clear the Liao River valley of Jurchen forces, a task

that he completed in 1216. After occupying the major cities of the region,

Mukhali went to Mongolia in the fall of 1217 to report to his sovereign.

Pleased with his work, Chinggis khan gave him the title of kuo-wang, or

"prince of the realm," and placed him in overall command of

a

new campaign

to seize those parts of north China still in Jurchen hands, that is, the land

south of the T'ai-ho Range.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

358 THE RISE OF THE MONGOLIAN EMPIRE

Mukhali returned to the south in the same year and set up military-

administrative headquarters at Chung-tu (now renamed Yen) and Hsi-ching

(modern Ta-t'ung). The forces at his disposal included 23,000 troops of the

left wing of the Mongolian army, augmented by 77,000 Chinese, Jurchen,

and Khitan auxiliaries that had either surrendered or defected to the Mongols

during the earlier fighting with the Chin. As a matter of policy the Mongols

encouraged and rewarded such defections, and the results had been gratify-

ing: Many Chin commanders, especially those of non-Jurchen origin, came

over with their units intact. It was the addition of these crucial auxiliaries,

which comprised three quarters of the troops available to Mukhali, that

enabled the Mongols to maintain unremitting pressure on the Chin even after

the greater part of their army, the center and right wing, had been with-

drawn from north China and committed in the west.

1

''*

In the initial phase of the new campaign, the Mongols launched a three-

pronged attack from Chung-tu and Hsi-ching designed to wrest Shansi,

Hopei, and Shantung from Chin control. Pushing into Hopei with the center

and main column, Mukhali soon encountered stiff

resistance.

Cities had to be

taken by direct assault, at high cost to both sides. On several occasions cities

won at such a high price were lost and had to be retaken. Though the going

was difficult, Mukhali was nonetheless making slow progress. In 1218,

leaving the Chin defector Chang Jou behind to consolidate Mongolian gains

in Hopei, Mukhali shifted his attention to Shansi.

T'ai-yiian, the main Chin bastion in the northwest of the province, was

taken in October, and the Mongols were then able to drive steadily to the

south. By the end of 1219 only the southernmost strip of Shansi remained

outside Mongolian control. Mukhali now returned to central Hopei and

received the surrender of

the

remaining Chin-controlled cities, including the

key garrison at Ta-ming, during the summer and fall of 1220. Thereafter he

pressed on into western Shantung, taking its chief city, Chi-nan, in October,

without a fight.

The relatively easy campaigning of 1220 was made possible by the Chin

dynasty's ill-advised military involvement in the south. In 1217, during the

lull in the fighting with the Mongols, the Chin emperor had foolishly

consented to open a campaign against the Sung, which had suspended its

tribute payments to the Jurchen court three years earlier. The series of annual

44 The number of troops available to Mukhali was carefully calculated by Huang Shih-chien in "Mu-hua-li

kuo wang hui hsia chu chiin k'ao," Yuan shih lun ts'ung, i (1982), pp.

57—71.

For accounts of the

campaign, see Igor de Rachewiltz, "Muqali, Bol, Tas and An-t'ung,"

Papers on

Far

Eastern

History, 15

(1977),

pp. 45—55; and Martin, The rise ofChingis khan, pp. 239—82. On the role of the Sung in the

Mongolian—Jurchen conflict of 1217—25, see Charles A. Peterson, "Old illusions and new realities:

Sung foreign policy, 1217—1234," in China

among

equals: The Middle

Kingdom

and its

neighbors,

10th-

14th

centuries,

ed. Morris Rossabi (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1983), pp. 204-20.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHINGGIS KHAN AND THE EARLY MONGOLIAN STATE 359

offensives launched by the Chin between 1217 and 1224 were often success-

ful on the local level, but they never brought decisive victory. The Sung,

refusing to negotiate despite initial setbacks, continued to resist and on one

occasion in the summer of 1219 even managed to destroy a major Jurchen

army in the Han valley.

The Chin decision to divide their military effort proved costly. The mar-

ginal gains at the expense of the Sung in no way compensated them for their

losses to the Mongols in the north and in the long run clearly undermined

their ability to cope with Mukhali's forces. Undaunted, however, in 1220 the

Chin mobilized a new army and prepared a counterthrust in the hope of

recouping some of their losses. Though initially formed, it appears, to strike

at eastern Shantung, where an army of anti-Jurchen Chinese rebels (the

Hung-ao or Red Coats) had been organized, the new force soon attracted

Mongolian attention. Once he became aware of

its

existence, Mukhali moved

south from Chi-nan in late 1220 and attacked the new Chin army at Huang-

ling kang, a ford on the south bank of the Yellow River not far from K'ai-

feng. He decisively defeated his foes, and with this victory the Mongols

extended their control over most of the Jurchen territory north of the Yellow

River, except for eastern Shantung, which remained in the hands of

the

Red

Coats,

and Shensi, which remained under Chin authority.

Placing Chinese defectors in charge of the surrendered areas, Mukhali

returned to the north, conducting mop-up operations along the way. In the

meantime, the Chin court, its counteroffensive having failed, sent an em-

bassy headed by Wu-ku-sun Chung-tuan to Chinggis khan in the west to

discuss possible terms. The Mongolian demands that the Chin emperor

accept the title of prince

(wang),

and thus recognize Chinggis khan as his

sovereign, and that Shensi be evacuated were, however, considered excessive,

and so the hostilities continued.

Mukhali renewed pressure on the Chin by initiating a major campaign in

Shensi and eastern Kansu (Kuan-chung) in

mid-1221.

After first crossing the

Ordos (with the acquiescence of the Tanguts, who also contributed auxiliary

contingents numbering fifty thousand), Mukhali spent the remaining part of

the year and the beginning of the next reducing the major cities of northern

and central Shensi. In the spring of 1222 he left one of his lieutenants,

Monggii Bukha, in charge of operations in Shensi and crossed the Yellow

River into Shansi to forestall a new Chin offensive in this quarter. In the

fighting that followed, the Mongols took Ho-chung and other fortified cities

along the river. In Shensi, meanwhile, Monggii Bukha had become bogged

down in extensive blockade operations. Even after the return of Mukhali and

his troops to Shensi in the fall of 1222, the Mongols were still unable to force

the capitulation of many key cities, including Ch'ang-an and Feng-hsiang.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

360 THE RISE OF THE MONGOLIAN EMPIRE

The sudden withdrawal of the Tangut auxiliaries at this critical juncture

further undermined the Mongols' military position. His striking power now

much reduced, Mukhali lifted the siege of Feng-hsiang in early 1223, and

following a brief retaliatory attack on the Hsi Hsia frontier, he moved back to

Shansi, where he shortly after fell ill and died (in March or April).

The deceased commander was immediately replaced by his brother,

Dayisun, but the Mongolian offensive had lost its momentum. Making the

most of this opportunity, the Chin hastily ended hostilities with the Sung,

moved its troops back into southern Shansi, and recovered some of the

territory previously lost to the Mongols. Supported by the Sung, with whom

they were loosely allied, the Red Coats also took advantage of

the

situation to

extend their hold in Shantung and, briefly, to seize territories in Hopei. This

latter move precipitated a rebellion by Wu Hsien, a former Chin commander

who had recently defected to the Mongols. In 1225 he changed sides once

again, this time throwing his lot in with the Sung. In the face of these

setbacks and Chinggis khan's determination to deal next with the perfidious

Tanguts, the Mongols had to content themselves with a holding operation in

north China for the following few years.

Administration of

north

China

The Mongols, as Chinggis khan himself recognized, knew little of the "laws

and customs of

cities"

and were ill equipped to undertake the administration

of complex sedentary societies on their own. It was therefore necessary to

recruit numerous technical specialists, particularly people with experience in

government or commerce who were willing to help the Mongols administer

and exploit the agricultural and urban populations under their control. Even

before his invasion of the Chin, Chinggis khan began building up a cadre of

such specialists from among the Khitan and Chinese officials who, for a

variety of reasons, left Chin service and submitted to the Mongols.

45

By the

time operations commenced against the Jurchens in 1211, Chinggis khan

had in his entourage a body of advisers who were intimately familiar with

both the Chin administrative system and conditions in north China.

As the Mongolian campaign gathered momentum, the number of defec-

tors increased markedly. Officials of Chinese origin were most numerous in

this second wave, but for the first time a few Jurchens also came over to the

Mongolian camp and offered their services. Civil officials who defected or

surrendered without resistance were routinely left in their old posts adminis-

45 In preparing this section I relied heavily on Igor de Rachewiltz's excellent study, "Personnel and

personalities in North China in the early Mongol period," Journal ofthe

Economic

and

Social History

ofthe

Orient, 9 (1966), pp. 88-144.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008