The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER

4

THE RISE OF THE MONGOLIAN EMPIRE

AND MONGOLIAN RULE IN NORTH

CHINA

MONGOLIA AND TEMOjIN, CA. II50-1206

Tribal

distribution

Toward the end of 1236 Mongolian armies under the direction of the great

general Siibetei crossed the Volga in force, the right wing moving north into

the Bulghar lands and the Russian principalities, and the left wing into the

north Caucasus and the western Qipchaq steppe. By the time the campaign

was called off in 1241, the princes of Russia had been subdued, and perhaps

even more important from the Mongolian point of view, the numerous

Qipchaq tribes, the last of the nomads of Eurasia to resist them, had been

brought under their control. All of the "peoples of the felt tent" from

Manchuria to Hungary were now members, through choice or compulsion,

of

a

vast nomadic imperium.

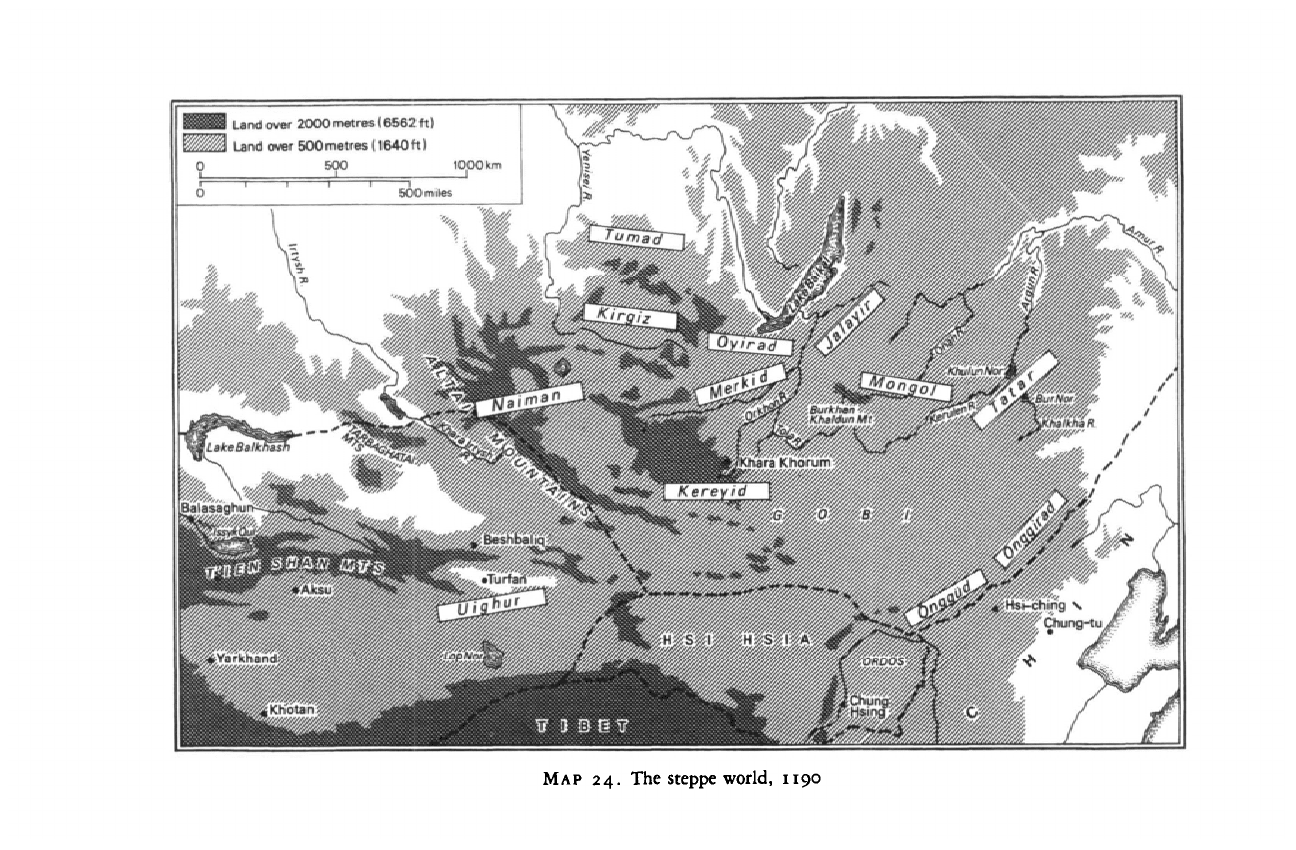

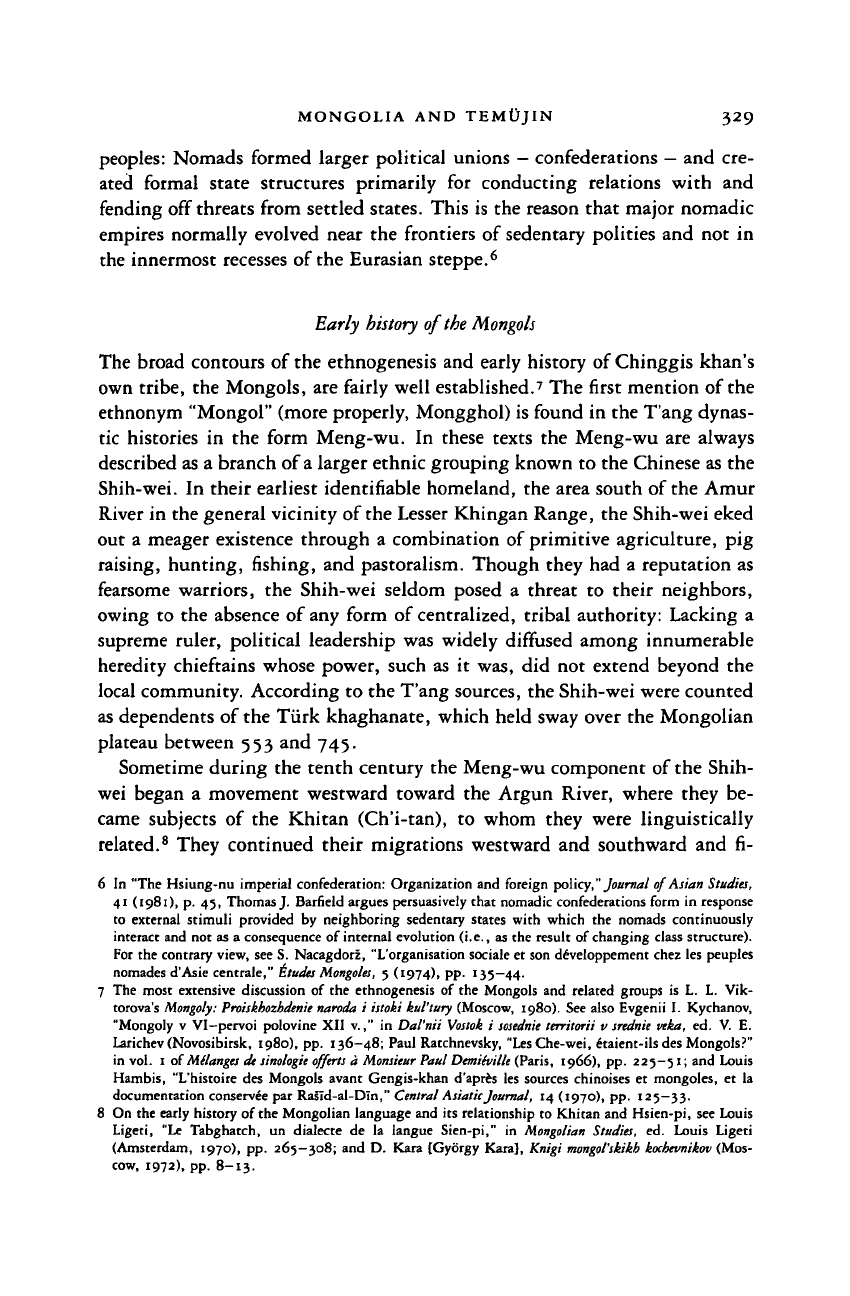

The unparalleled unification of the steppe tribes under the aegis of the

Mongols in the thirteenth century stands in sharp contrast with the divi-

sion and discord of the twelfth century (see Map 24).'The level of politi-

cal and social integration in this period was most often the individual

tribe or, at best small, unstable confederations of tribes. The strongest of

these confederations, the Qipchaq in the west and the Khara Khitan in

Jungaria, were able, it is true, to dominate sections of the steppe and its

immediate hinterland, but they were nonetheless pale and imperfect imita-

tions of the great nomadic empires of the past, such as those created by

the Hsiung-nu, Turks, or Khazars. This lack of political unity was

equally characteristic of the eastern end of the steppe. Some tribes

(irgen)

of the Mongolian plateau did maintain their internal cohesion, but others

disintegrated into their constituent elements - clans

(obogb),

which then

became independent entities competing with one another for pastures, po-

litical leadership, and the favors of their sedentary neighbors. Although

historical data on the principal tribes of Mongolia, which served as the

initial building blocks of the Chinggisid empire, are limited, their geo-

321

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Land

over 2000metres (6562 ft)

Wffk Land over 500metres (1640ft)

0 500 1000 km

MAP

24. The steppe world, 1190

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MONGOLIA AND TEMtJJIN 323

graphical distribution and the level of their internal integration are known

in broad outline.

1

The westernmost of the tribes, the Naiman, were probably of Turkic

origin. They inhabited the southern slopes of the Altai Range and the upper

course of the Irtysh River. The Naiman were a fairly cohesive and stable

group with permanent leaders

{khans)

until the end of the twelfth century

when a rivalry within the ruling family effectively destroyed their unity.

Culturally, the Naiman were generally more advanced than were the tribes of

central and northern Mongolia, owing to their close proximity to the centers

of Uighur civilization located in the Turfan depression and on the northern

slopes of the T'ien-shan Range. The Naiman learned various administrative

techniques from their sophisticated, sedentary neighbors to the south, and

they shared as well a common religious heritage, a form of Nestorian Chris-

tianity much influenced by indigenous shamanistic practices.

The Kereyid, to the east of the Naiman, also professed Nestorian Christian-

ity under the influence of their neighbors. Throughout the twelfth century

they enjoyed stable leadership and some degree of political unity. The core of

their territories was in the upper reaches of the Selenga and Orkhon River

valleys, a region that for both strategic and ideological reasons had long

played a pivotal role in the formation of all successful nomadic confederations

in the eastern steppe.

The southeastern zone of the Mongolian plateau, the heart of the Gobi

region, was inhabited by the Turkic-speaking Onggiid. Their principal settle-

ment, T'ien-te

—

Marco Polo's Tenduc

—

was located just north of

the

loop of

the Yellow River near the strategic Ordos Desert, which formed the frontier

between the Chin dynasty and the Tangut, or Hsi-Hsia, kingdom. The well-

established Onggiid princely house, who were firm adherents of Nes-

torianism, considered themselves, at least nominally, vassals of the Jurchens.

The Onggirad, or Khonggirad, to the north of the Onggiid, occupied the

western slope of the Great Khingan Range. They were in contact with the

Chin dynasty by the late twelfth century and appear at that time to have been

rather loosely organized under several different chiefs. The Onggirad regu-

larly exchanged brides with the Mongols, their immediate neighbors to the

west, a practice that was continued after the founding of the empire.

The steppe region to the south of

the

Keriilen River was the domain of one

of the more powerful and aggressive tribes of the Mongolian plateau, the

Tatars, who, at the instigation of the Chin, played an active role in the

politics of the steppe. In their efforts to keep the nomads divided and their

1 Louis Hambis, Gengii khan (Paris, 1973), pp. 7—22, provides a succinct discussion of the history and

distribution of the peoples of Mongolia in the twelfth century, on which I have drawn freely. Though

this work is a popular survey, it rests on extensive research.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

324 THE RISE OF THE MONGOLIAN EMPIRE

own frontiers secure, the Jurchens assiduously promoted conflict between the

Tatars and neighboring tribes, particularly the Kereyid and Mongols. Owing

to the great success of this policy, feuding among these tribes, carried on

with a murderous intensity, became endemic by the mid-twelfth century.

Chinggis khan's own tribe, the Mongols, lived between the Keriilen and

Onan rivers, that is, just to the north of the Tatars. Throughout the third

quarter of the twelfth century they were sharply divided among themselves

and thus frequently fell victim to the depredations of their neighbors (see

section "Early history of the Mongols"). Of all of the nomads of the eastern

steppe, the Mongols were perhaps the most divided and the least likely, it

would seem, to provide the leadership that would unify the "peoples of the

felt tent."

To the northwest of the Mongols were the lands of the Three Merkid.

Divided, as their name suggests, into three

branches,

each

with

its

own leader,

the Merkid ranged along the lower course of the Selenga, south of

Lake

Baikal.

Though they occasionally combined forces to undertake raids on their neigh-

bors,

the Three Merkid, like other tribes in or near the forest zone - such as

the Kirgiz of the upper

Yenesei

and the Oyirad living immediately west of Lake

Baikal - did not possess a high degree of internal cohesion.

The social order

These tribes of Mongolia, as was the case among the steppe nomads in

general, were constructed from a varying number of hypothetically related

lineages,

obogh,

that traced their ancestry back through the paternal line to a

putative founder.

2

Because its membership was deemed to be of one bone

(yasun),

that is, descended from a common progenitor, the lineage was an

exogamous unit that regulated marriage. Its leadership determined migra-

tion routes, distributed pasturelands, organized hunts and raids, and made

political decisions concerning entrance into or withdrawal from tribal confed-

erations. A distinctive feature of these lineages is the frequency and ease with

which they bifurcated: When lineages increased in number or experienced

internal discord, they segmented into sublineages that in turn could multi-

ply and develop into new lineages. Because sublineages were frequently in

the process of splitting off the original stem and becoming lineages in their

own right and, further, because large, militarily successful lineages acquired

many of the characteristics of a tribe, there is considerable vagueness and

2 On Mongolian society and economy, see Sechin Jagchid and Paul Hyer, Mongolia's

society

and culture

(Boulder, 1979), pp. 19—72, 245-96; B. Vladimirtsov, Le rigimesocialdes Mongols: Le

Feodalisme nomade

(Paris,

1948), pp. 39-158; and Elizabeth E. Bacon, Obok, a study of

social

structure in Eurasia (New

York, 1958), pp. 47-65.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MONGOLIA AND TEMOjIN 325

confusion

in the

sources regarding social nomenclature, and this makes

it

difficult to establish the exact status of an individual segment or its relation-

ship to other segments

at

any given time.

Though defined

in

genealogical terms,

the

lineage

and the

tribe were

essentially political entities composed of individuals whose ties of blood were

more often fictive than real.

In

the steppe, common political interest was

typically translated into the idiom of kinship. Thus, the genealogies of the

medieval Mongols (and other tribal peoples) were ideological statements

designed

to

enhance political unity, not authentic descriptions of biological

relationships. This explains why political formations based on such lineages

and tribes, themselves arbitrary and temporary constructions, were by nature

dynamic, flexible, and unstable.

It

also explains why nomadic confederations

and empires coalesced with such lightning speed and then just

as

rapidly

disintegrated as

a

consequence of internal tension or external pressure.

3

Below the level of the lineage and sublineage was the nomadic camp,

the

ayil. This was the basic production unit

in

the Mongols' pastoral economy,

normally consisting of a single extended family with its own tents

(ger)

and

herds.

For purposes of cooperative labor

or

local defense, several ayil might

temporarily come together

to

form

a

giire'en,

literally

a

"circle," that

is, a

lager or encampment encircled by tents and wagons.

Besides the division into descent groups, Mongolian society was separated

into several loosely constructed estates

-

nobles, commoners,

and

depen-

dents.

The nobles advanced claims to such status as the direct descendants of

a lineage's eponymous progenitor. This estate provided political leadership

for lineages and tribes. There were, however, no strict rules of succession or

appointment to positions of authority, and there was considerable latitude

in

selecting leaders. In the main they were chosen on the basis of their personal

attributes and experience, through an informal consensus of prominent mem-

bers of the lineage. Proper genealogical credentials were, of course, an asset

but not a necessity; noble antecedents could always be fashioned to accommo-

date an able and successful leader. For elevation to the rulership of a tribe or

confederation,

a

more formal procedure was adopted

—

the convocation of a

diet, or khuriltai, composed of nobles and worthies.

The junior and collateral lines of the descent group formed the commonal-

ity, called the "black hairs"

or

"black heads," that made

up

the bulk of the

population. The nobles normally possessed larger herds and enjoyed access

to

the best pasturelands, but no sharp social distinction was drawn between the

two estates, nor was there any dramatic difference in life-style. At the bottom

3 See the discussion in Rudi Paul Lindner, "What was a nomadic tribe?"

Comparative Studies in Society and

History,

24 (1982), pp.

689-711.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

326 THE RISE OF THE MONGOLIAN EMPIRE

of the social scale were found the

bo'ol,

slaves or bond servants, usually acquired

in raids on nearby tribes or sedentary peoples. Both single persons and entire

descent groups could be made the dependents of

others;

that is, an individual

could become the personal bond servant of his captor, and a lineage, or part

thereof,

defeated in battle might collectively become the dependents, or cli-

ents,

of the victorious

obogh.

Bo'ol, whether individuals or parts of lineages,

were obliged to work for their masters as domestics, herders, or agricultural

laborers and to take up arms on their behalf in time of war. Though clearly in a

subordinate position,

bo'ol

were often treated as part of the family and achieved

de facto freedom even without formal manumission.

The

nb'kb'd

(singular,

nb'kor),

or "companions," of major lineage chiefs or

tribal khans were another important estate in medieval Mongolian society.

They formed the retinue of an aspiring chief or khan, providing him with

military and political advice and undertaking in general any commission

desired by the lord, from tracking down stray animals to acting as his

personal emissaries in diplomatic negotiations. In return for their service, the

nb'kb'd

received protection, provisions, and food. True boon companions, they

fought, lived, ate, and drank with their master. The

nb'kb'd

were recruited

from all social strata. Some were members of the nobility who by free

association attached themselves to a ruler of a tribe or lineage not his own,

and some were bo'ol who had demonstrated their ability and loyalty on the

battlefield, for example, the famous commander Mukhali, whom Chinggis

khan elevated from dependent to companion status. Though socially diverse,

the

nb'kb'd

did share one common characteristic: None, so far as we know, were

blood kin of their masters.

Structurally, then, the tribes of twelfth-century Mongolia were fairly com-

plex entities. Typically, the core of such a tribe was composed of lineages and

sublineages that for political purposes claimed a common ancestry based on a

communally recognized but artificially contrived genealogy. Attached to the

core were various nonkinsmen: lineages associated through marriage, depen-

dent individuals and client lineages made subordinate through military de-

feat and capture, and

nb'kb'd

recruited from various external sources.

Economic conditions

The primary occupation of the inhabitants of the Mongolian plateau was

herding domesticated animals. Each of the five principal types of animals

kept by the Mongols

—

horses, sheep, camels, cattle, and goats - had its

specific uses, and was valued according to a well-established order of prece-

dence. Horses, the prized possession of the pastoral nomads, were used as

military mounts, for transportation, and for herd control. Without them, the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MONGOLIA AND TEMOjIN 327

extensive, mobile economy of the steppe nomad would have been impossible.

In second place and by far the most numerous of the herd animals were sheep,

which together with goats, the lowest category, supplied meat and wool.

Third in precedence were camels, employed as beasts of burden mainly in the

arid Gobi region to the south. The fourth-ranked long-horned cattle, also

found in substantial numbers, contributed meat, hides, and transportation.

The famous large-wheeled carts (ger

tergen)

that carried the tents of tribal

leaders were pulled by teams of oxen. All of the animals provided milk, the

by-products of which, such as ayiragh (fermented mare's milk, the Turkic

kumis),

yoghurt, and various kinds of cheese, were staples in the Mongols'

diet. Even the droppings of the animals were used, serving when dried as the

major source of fuel in the barren steppe.

The frequent controlled movement of the herds in search of water and

fodder was neither aimless nor unbounded. There was a well-established

annual cycle from spring to summer to winter camp; the latter, often shared

by several related ayils, was usually a more permanent facility situated in a

protected river valley. Because their herds were complex, composed of ani-

mals with different rates of movement and divergent food and water require-

ments, the herder at migration time had to make very fine calculations

concerning daily distances traveled, routes taken, anticipated weather condi-

tions,

and the like to accommodate the disparate needs of his beasts. Any

major migration of their complex herds (together with people and posses-

sions) was thus a complicated problem in logistics requiring careful planning

and execution - training that the Mongols were later to put to good use in

their far-ranging military campaigns.

Given the harsh environmental conditions and the consequent limited capac-

ity of the Mongolian plateau to sustain herds of

beasts,

it was essential that the

nomads distributed themselves evenly over all the available pasturage. One of

the crucial functions of the lineage was to facilitate a peaceful distribution, to

adjudicate internal disputes over grazing land, and to protect its members

from outside competitors. Individual herdsmen therefore thought in terms of

guaranteed seasonal access to portions of the lineage's territory rather than of

personal, permanent ownership of land - in other words, usufruct rather than

proprietary rights.

Although the Mongols had a strong commitment to pastoral nomadism,

hunting also played a role in their economy. It augmented their food supply,

provided furs and hides for clothing or trade, and helped control populations

of predators, especially wolves, that were a constant threat to their herds.

Large-scale cooperative hunts on the lineage or sublineage level functioned as

a form of military training, sharpening individual skills and promoting

coordination among formations drawn from various kinship groupings.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

328 THE RISE OF THE MONGOLIAN EMPIRE

In the forested regions of southern Siberia, the relative importance of

hunting in the tribal economy increased substantially, so much so that the

medieval Mongols always distinguished the "peoples of the forest,"

hoi-yin

irgen,

from those who lived in the steppe. Though hunting was their main-

stay, the tribes of Siberia - Oyirad, Buriats, Khori Tumad, and so forth -

had horses, pursued a nomadic (albeit nonpastoral) life-style, and were always

considered part of the basic manpower pool on which expanding, steppe-

based tribal confederations customarily drew.

Agriculture was not an independent branch of the nomad's domestic econ-

omy, but it was not unknown among the peoples of

Mongolia:

The Siberian

tribes,

at least those in the Yenesei region, cultivated fields, as did the

Onggiid along the Great Wall. In fact, none of the pastoralists of the Eur-

asian steppe could claim a purely nomadic economy, unconnected with and

untouched by the sedentary world. Indeed, pure nomadism is a hypothetical

construct, not a social reality. Pastoral nomadism can most usefully be

viewed as a continuum that ranges from near sedentary transhumant commu-

nities to a theoretically possible, but never realized, "pure" form of nomad-

ism, that is, a society deriving everything it uses or consumes from its own

herds.

4

The need for supplemental winter food and forage for the herds and

the desire for luxury goods such as tea and textiles was ever present among

the nomads. And because their own economy could never fully meet the

demand for these goods, nomads were necessarily compelled to turn to their

sedentary neighbors for agricultural products. In the case of the tribes of

Mongolia, this meant continuous economic interaction with China. The

preferred means of acquiring the desired products was the payment of "trib-

ute"

in the form of furs, hides, horses, or whatever to the Chinese in return

for "bestowals," such as grain, metal implements, and luxury items. If the

Chinese, who were largely self-sufficient, refused the proffered exchange, the

nomads would threaten force. In short, the steppe people used war and the

threat of war to extort the right to offer tribute to the Middle Kingdom.

This economic exchange always involved the nomads in an intricate web of

political relationships with the Chinese, who used the tributary system as a

means of controlling or manipulating the barbarians for their own ends.

Thus,

from the Chinese standpoint, the purpose of the bestowals

—

goods,

noble titles, or brides - was, on the whole, political rather than economic'

Interaction of this nature provided an important impetus, though un-

intended on the part of the Chinese, for state formation among the steppe

4 Douglas L. Johnson, The nature of

nomadism:

A

comparative

study of pastoral

migrations

in

southwestern

Asia

and

northern

Africa (Chicago, 1969), pp. 1-19, discusses the concept of

a

nomadic continuum.

5 These points are brought out with great clarity by Sechin Jagchid in "Patterns of trade and conflict

between China and the nomads of Mongolia," Zentralasiatische

Studien,

11 (1977), pp. 177-204.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MONGOLIA AND TEMOjIN 329

peoples: Nomads formed larger political unions

—

confederations

—

and cre-

ated formal state structures primarily

for

conducting relations with

and

fending off threats from settled states. This is the reason that major nomadic

empires normally evolved near the frontiers of sedentary polities and not

in

the innermost recesses of the Eurasian steppe.

6

Early history of the Mongols

The broad contours of the ethnogenesis and early history of Chinggis khan's

own tribe, the Mongols, are fairly well established.

7

The first mention of the

ethnonym "Mongol" (more properly, Mongghol) is found in the T'ang dynas-

tic histories

in

the form Meng-wu.

In

these texts the Meng-wu are always

described as a branch of a larger ethnic grouping known to the Chinese as the

Shih-wei. In their earliest identifiable homeland, the area south of the Amur

River in the general vicinity of the Lesser Khingan Range, the Shih-wei eked

out

a

meager existence through

a

combination of primitive agriculture,

pig

raising, hunting, fishing, and pastoralism. Though they had

a

reputation as

fearsome warriors,

the

Shih-wei seldom posed

a

threat

to

their neighbors,

owing

to

the absence of any form of centralized, tribal authority: Lacking

a

supreme ruler, political leadership was widely diffused among innumerable

heredity chieftains whose power, such as

it

was, did not extend beyond

the

local community. According to the T'ang sources, the Shih-wei were counted

as dependents of the Turk khaghanate, which held sway over the Mongolian

plateau between 553 and 745.

Sometime during the tenth century the Meng-wu component of the Shih-

wei began

a

movement westward toward the Argun River, where they be-

came subjects

of

the Khitan (Ch'i-tan),

to

whom they were linguistically

related.

8

They continued their migrations westward and southward and

fi-

6 In "The Hsiung-nu imperial confederation: Organization and foreign

policy,"

Journal

of Asian

Studies,

41 (1981), p. 45, Thomas J. Barfield argues persuasively that nomadic confederations form in response

to external stimuli provided

by

neighboring sedentary states with which

the

nomads continuously

interact and not as a consequence of internal evolution (i.e., as the result of changing class structure).

For the contrary view, see S. Nacagdorz, "L'organisation sociale et son deVeloppement chez les peuples

nomades d'Asie centrale,"

Etudes

Mongo/es,

5 (1974), pp. 135—44.

7 The most extensive discussion

of

the ethnogenesis

of

the Mongols and related groups

is L. L. Vik-

torova's

Mongoly:

Proiskhozhdenie naroda

i

istoki kul'tury

(Moscow, 1980). See also Evgenii

I.

Kychanov,

"Mongoly

v

VI—pervoi polovine XII

v.," in

Dal'nii Vostok

i

sosednie

territorii

v

srednie veka,

ed. V. E.

Larichev (Novosibirsk, 1980), pp. 136—48; Paul Ratchnevsky, "LesChe-wei, £taient-ils des Mongols?"

in vol. 1 of Milanges de

sinologie offerts

a

Monsieur Paul Demihiille (Paris, 1966), pp.

225-51;

and

Louis

Hambis, "L'histoire des Mongols avant Gengis-khan d'aprts les sources chinoises

et

mongoles,

et la

documentation conservee par RasTd-al-DIn,"

Central

Asiatic Journal, 14 (1970), pp. 125—33.

8 On the early history of the Mongolian language and its relationship to Khitan and Hsien-pi, see Louis

Ligeti,

"Lc

Tabghatch,

un

dialecte

de la

langue Sien-pi,"

in

Mongolian

Studies,

ed.

Louis Ligeti

(Amsterdam, 1970), pp. 265—308; and D. Kara [Gyorgy

Kara],

Knigi

mongol'skikh kocbevnikov

(Mos-

cow, 1972), pp. 8—13.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

33O THE RISE OF THE MONGOLIAN EMPIRE

nally established themselves in the Onan—Keriilen area during the eleventh

century. The movement of the Meng-wu from northern Manchuria to eastern

Mongolia required an increased commitment to the pastoral elements of their

mixed economy. New animals, camels and sheep, were added to their herds

of cattle and horses, and the part-time, limited pastoralism of the forest zone

gave way to the full-time, extensive pastoralism typical of the steppe.

The Mongols' own legendary account of their origin does not indicate their

original home and only hints at the migration that brought them to the

Onan—Keriilen region. According to this creation myth, which is contained

in the

Secret

history,»

the progenitors of the Mongolian people were a blue-

gray

wolf,

whose birth was ordained by Heaven, and a fallow doe, whose

origin is left unexplained. Departing from an undisclosed clime, the couple

crossed a sea or lake, also unnamed, and then occupied the region around

Burkhan Khaldun, a mountain now identified with Khentei Khan in the

Khentei Range near the headwaters of the Onan and Keriilen. Here was born

the only offspring of this union, Batachikhan, a human male, from whom all

the numerous Mongolian lineages originated.

In the eleventh generation, we are told, a descendant of Batachikhan

named Dobun Mergen married a young woman, Alan Gho'a, of the Khorilar

lineage. She bore her husband two sons during his lifetime, and after Dobun

Mergen's demise she gave birth to three additional sons fathered by a super-

natural being riding on a moonbeam. The youngest of the three, Bodenchar,

was the founder of the Borjigin

obogh,

the most ancient of the Mongolian

lineages, into which Temiijin, the future Chinggis khan, would later be

born.

This genealogy of Chinggis khan's early ancestors, although full of fanciful

and mythical elements, reveals several interesting features of Mongolian

social structure that have important historical implications. First, the line

between Batachikhan and Chinggis khan is not reckoned solely on the basis

of paternal descent, as one would expect. A woman, Alan Gho'a, by the

Mongols' own "official" accounting, is a vital link in the genealogical chain

leading from the mythical past to the historical present. Her prominent and

honored position in an otherwise exclusively male line of descent points up

the high status of women in Mongolian society and anticipates the crucial

role they later were to play in the emergence and consolidation of the empire.

Second, tribes as well as lineages had mythical ancestors. Although in theory

9 See Francis Cleaves, trans., The

secret

history of the

Mongols:

For

the first time

done

into English

out

of the

original

tongue, andprovidedwithexegeticalcommentary (Cambridge, Mass., 1982), sec. 1-42 (pp. 1-10) (hereafter

cited as

Secret

history). For a comparison of the Mongols' creation myth with those of the Turks and other

Inner Asian peoples, see Denis Sinor, "The legendary origin of the Turks," in

Folklorica:

Festschrift for Felix

J. Oinas, ed. Egle Victoria Zygas and Peter Voorheis (Bloomington, 1982), pp. 223—57.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008