?tekauer Pavol, Lieber Rochelle. Handbook of Word-Formation

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

290

PETER A

C

KEMA

&

A

D NEELEMAN

2

.2 Haplology

W

hereas the most basic cases of competition between morphemes are governed

b

y

the Elsewhere Principle onl

y

, there are various t

y

pes

o

f com

p

etition that involve

o

ther conditions. Once such condition is what Menn and MacWhinne

y

(1984) call

t

h

e

Re

p

eated Mor

p

h Constrain

t

,

a condition disfavourin

g

ad

j

acent morphemes that

h

ave an identical (or very similar) fo

r

m. Suppose that there are two adjacent

p

ositions P

1

an

dP

2

in the morphosyntactic structure of some word. Suppose,

furthermore, that if we look at the s

p

ecifications of the mor

p

hemes in the lexicon of

t

he language and simply apply the Elsewhere Principle, we would expect

P

1

t

obe

s

pelled out by

m

1

,

while P

2

would be spelled out by

m

2

.

I

fm

1

an

dm

2

ha

ve

an

i

dentical form

,

or if

m

1

ends in a string identical to m

2

,

languages may choose a

s

pell-out different from

m

1

-m

2

,

in order to avoid a violation of the Re

p

eated Mor

p

h

C

onstraint.

There are four strate

g

ies in which lan

g

ua

g

es deal with violations of the Repeated

Morph Constraint. The first is to simply tolerate the violation, as happens in the

English comparative of

cleve

r

,

which is

cleve

r

e

r. The second is to rule out s

p

ell-out

o

f the morphosyntactic construction in question altogether. This applies to a case

l

ike English

*

uglil

y

,

for which a circumscription is required, such as

i

n an ugly wa

y

.

In addition to this, one of the offending morphemes can fail to be spelled out

s

eparately, or it can be spelled out by a form which is not normally the optimal spell-

o

ut for the feature combination in question. We will now discuss some examples of

the latter two strate

g

ies.

A simple case of non-spell-out is presented by the English genitive of plural

n

ouns. Since both the genitive and the plural are marked by -

s

,

the genitive of a

p

lural noun should end in

-s

-

s

.

But in fact, such ex

p

ressions end in

-s

(

see

(

7c

))

.

N

ote that there is no problem in the genitive -

s

attaching to irregular plurals (see

(

7d), so that we indeed seem to be dealing with a case of haplology, rather than with

m

orphological incompatibility of plural and genitive. Note, moreover, that the

g

enitive -

s

can be attached to certain underived words endin

g

in /s/, showin

g

that we

are not dealin

g

with a purel

y

phonolo

g

ical phenomenon either (see (7e)). (The issues

i

nvolved are discussed in more detail in Yip 1998)

(7) a. The girl’s house

b. *The girls’s house

c. The girls’ house

d.

Th

ewo

m

e

n’

s

h

ouse

e. Professor

S

.’s lectures

A similar pattern is found in Spanish c

l

itic clusters. Grimshaw (1997) points out

that at least in some dialects a sequence of a reflexive and an impersonal clitic,

ex

p

ected to surface as a

se se

sequence, surfaces as a single clitic instead:

(

8

)

Se

(

*se

)

lava

one oneself washes

‘

O

ne washes oneself’

WO

R

D

-

FO

RMATI

O

N IN

O

PTIMALITY THE

O

RY

29

1

The fourth strategy to deal with repeated morph cases, which consists of spelling

o

ut one of the offending morphemes by using an ‘unexpected’ candidate, can also be

i

llustrated by clitic clusters. In certain variants of Italian, in structures comparable to

(8) one of the clitics is realized by a clitic (

ci

)

that is used otherwise for the first

person plural (see Bonet 1995 and Grimshaw 1997):

(9) a. Lo si sveglia Impersonal

si

3.

A

CC

I

MPER

S

wakes.up

S

‘One wakes him u

p

’

b. Se lo com

p

ra Reflexivese/si

REFL

3-

ACC

-

buys

C

‘S/he buys it for himself/herself’

c. Ci/*Se si lava Impersonal plus reflexive

I

MPERS REF

L

washes

‘

o

n

ew

a

s

h

es o

n

ese

lf’

A

similar case from Spanish is the phenomenon known as ‘spurious

se

’

(

see

Perlmutter 1971 and Bonet 1995

)

. Where one would ex

p

ect to find a se

q

uence of the

t

hird

p

erson dative clitic

le

and the third

p

erson accusative clitic

lo

,

the dative is

r

eplaced by

se

,

a clitic that is otherwise used in various different structures

(

such as

i

mpersonal, reflexive and unaccusative struc

t

ures). Note, by the way, that this

tt

e

xample demonstrates that the Repeated Mo

r

ph Constraint is violated by two forms

t

hat are phonolo

g

icall

y

similar, but not absolutel

y

identical, somethin

g

we cannot

g

o

i

nt

o

h

e

r

e.

(10) a. El premio, lo dieron a Pedro aye

r

the

p

rize 3

ACC

gave-3

C

PL

to Pedro yesterda

y

‘The prize, they gave it to Pedro yesterday’

b. A Pedro, le dieron el premio aye

r

to Pedro

,

3

DAT

gave-3

T

PL

the prize yesterda

y

‘Pedro, they gave the prize to him yesterday’

c. A Pedro, el premio, se/*le lo dieron a

y

e

r

to Pedro, the prize,

SE

/3

E

E

DA

T

3

T

ACC

gave-3

C

P

L

y

esterda

y

N

ote that, although they both involve suppletion, there is a difference between

t

he cases in

(

9

)

and

(

10

)

. In the for

m

er, a violation of the Re

p

eated Mor

p

h

C

onstraint is avoided by using a clitic that is more richly specified than the clitic it

r

eplaces (the first person feature of

ci

is not present in morphosyntax). In the latte

r

c

ase, a clitic is used that spells out less features than are p

r

esent in morphosyntax

(ar

g

uabl

y

, the clitic

se

is hi

g

hl

y

underspecified; it certainl

y

lacks the number and

c

ase features present in

le

).

In the rest of this section we will discuss wh

y

an anal

y

sis in terms of

c

ompetition, and more specifically an OT a

ccou

nt in

w

hi

c

h f

o

rm

s

ar

eev

al

u

at

ed

against a set of ranked, violable constraints, may be the best way to deal with some

292

PETER A

C

KEMA

&

AD NEELEMAN

properties of repeated morph effects (in particular the cross-linguistic variation we

s

ee in the way the problem is dealt with).

I

n structures that potentially violate the Repeated Morph Constraint, various

factors come into play. The first is, of c

o

urse, the Repeated Morph Constraint itself

(

see (11a). We have already encountered

so

m

eo

th

e

r

co

n

d

iti

o

n

s

in

sec

ti

o

n 2

.

1

(

where we treated them as unviolable

).

For a start

,

each feature bundle in the

m

orphos

y

ntax should receive a realiza

t

ion in the morphophonol

og

ical output. We

will split this condition into

t

wo constraints. The first requires a transparent match

between morphos

y

ntactic structure and morphophonolo

gy

: it is violated if there is a

l

ack of one-to-one mapping between the two (see (11b)). The second requires that

phi-features are realized by phonological material that is specified for the right

features (see (11c)). Finally, no features may be spelled out that are absent in the

m

orphosyntax. Thus, affixes that are lexically specified for some feature F may not

be used for inputs that lack F (see (11d)). These constraints are independently

m

otivated, in that they play an essential role in the analysis of various othe

r

l

in

g

uistic phenomena (note that the Repeated Morph Constraint can be seen as a

subc

a

se o

f th

e

O

bli

g

ator

y

Contour Principl

e

)

.

(

11

)

a. Re

p

eated Mor

p

h Constrain

t

*

M

1

M

2

if M

1

=

M

2

b.

Iconicit

y

One element in the morphophonological structure is the realization

o

f one element in the morphosyntactic structure

c.

P

a

r

se

Assi

g

n to each feature in the

m

orphos

y

ntax a properl

y

specified

m

orpho-phonolo

g

ical realization

d.

Faithfulness

The morphophonology does not realize features absent in the

m

orphosyntax

I

n the OT conception of grammar, (11 a-d) must be violable constraints that are

r

anked in a language-particular order with r

e

s

pect to each other and with respect to

o

th

e

r

co

n

s

traint

s.

Let us therefore consider the patterns of constraint violation induced b

y

the

l

o

g

icall

y

possible strate

g

ies to deal with repeated morphs. Suppletion with an

o

vers

p

ecified form involves the use of a mor

p

heme that s

p

ells out more features

t

han are

p

resent in the mo

r

phosyntactic input. This satisfies all conditions except

F

aithf

u

ln

ess.

Suppletion with an underspecified form satisfies Faithfulness, but violates Parse.

There are two related strategies that underparse the input. The first is not to realize

o

ne of the offendin

g

morphs. This violates Parse, but also Iconicit

y

. The second is to

n

ot realize the morphos

y

ntactic input at all; t

h

at is, to use the so-called null parse. Of

c

ourse this violates Parse, but it ar

g

uabl

y

does not violate Iconicit

y

: since there is no

m

orphophonological structure, the morphophonology cannot be non-iconic either.

A

further strategy is to associate the two morphosyntactic feature bundles to a

s

ingle phoneme (whose form will of course b

e

suitable to spell out both, given that

W

OR

D

-

F

ORMATION IN OPTIMALITY THEORY

293

we are dealing with repeated morphs). Thi

s

coalescence strategy satisfies Parse, as

well as Faithfulness

,

but it violates Ic

o

nicity, as it involves two-to-one mapping

between morphosyntax and morphophonology.

Finall

y

, repeated morphs can be tolerated, somethin

g

that obviousl

y

violates the

R

epeated Morph Constraint, but none of th

eo

th

e

r

co

n

d

iti

o

n

s.

Th

ev

ari

ous co

n

s

traint

v

iolation patterns are

g

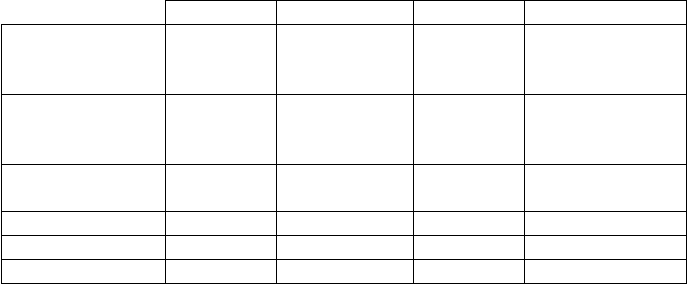

iven in Table 1. (The asterisk between brackets in the column

u

n

de

r Par

se

in

d

i

c

at

es

that th

e

n

u

m

be

r

o

f

v

i

o

lati

o

n

so

f thi

sco

n

s

traint that i

s

in

duced

by the null parse depends on the number of features that are present in the

m

orphosyntactic structure).

The ranking of the four constraints determines which strategy is employed. The

c

rucial factor is which constraint is ranked lowest.

(

i

)

If this is Faithfulness, we will

g

et suppletion with an overspecified form. (ii) If it is Parse, there are two

possibilities, namel

y

suppletion with an und

e

r

s

p

ecified form and avoidance. Which

o

f these is chosen de

p

ends on the lexical

i

nventor

y

of the lan

g

ua

g

e. Given that Parse

p

refers the s

p

ell-out of some features

o

ver the s

p

ell-out of none, su

pp

letion will

block avoidance whenever there is a

p

honeme that can realize a subset of the

features in the morphosyntactic input. In

t

he absence of such a phoneme, we will get

avoidance, that is, the repeated morph con

s

t

ruction is not allowed to surface.

(

iii

)

If

Iconicity is the lowest ranked constraint, the best solution is to link both

m

orphosyntactic feature bundles to a single phoneme. Finally, (iv) if the Repeated

Morph Constraint itself is ranked lowest, the result is tolerance of repeated morphs.

G

iven that the four strate

g

ies result from the low rankin

g

of four different

c

onstraints, an OT-account alon

g

the lines

j

ust sketched would appear to be purel

y

descriptive. However, such an analysis has two potentially attractive properties. The

fir

s

t i

s

that it r

u

l

es ou

t

de

l

e

ti

o

n a

s

a

s

trat

e

g

y. This is because it incurs violations on

both Iconicity and Parse. Since there are strategies that violate only Iconicity

(namely coalescence) or only Parse (namely avoidance and suppletion with an

u

nderspecified form), deletion will not be

t

he optimal strategy under any ranking of

t

he constraints (in the terminolo

gy

of OT, the candidate involvin

g

deletion is

RM

C

Iconicit

y

Par

se

Faithf

u

ln

ess

Su

pp

letion

(

overs

p

ecified

form

)

*

Suppletion

(

underspecified

form

)

*

A

vo

i

d

an

ce

(

null parse)

*

(

*

…)

C

oalescenc

e

*

D

e

l

e

ti

o

n * *

T

o

l

e

ran

ce

*

Ta

b

l

e2

2

94

PETER A

C

KEMA

&

A

D NEELEMAN

h

armonically bounded by the candidates involving the other strategies jus

t

m

entioned

)

. This im

p

lies that in all cases where repeated morphs are spelled out by a

single phoneme, this phoneme must be associated with both morphemes, rather than

with

j

ust one of them. It might seem that this is a difficult prediction to test, but

r

ecently De Lacy (1999) has provided empi

r

i

c

al

ev

i

de

n

ce

that

i

n

d

i

c

at

es

that th

e

re

l

ev

ant

c

a

ses

in

deed

in

vo

l

ve co

al

esce

n

ce

rath

e

r than

de

l

e

ti

o

n

.

A

second potentiall

y

correct prediction is that suppletion strate

g

ies can onl

y

appl

y

to forms that are part of a paradi

g

m, and not to derivational affixes,

c

ompounds and the like. Suppletion onl

y

make sense if there are morphemes whose

feature s

p

ecification is either a su

p

erset or a subset of one of the feature bundles

present in morphosyntax. Such elsewhere relations typically hold of functional

m

or

p

hemes

(

see section 2.1

)

, but not of lexical ones. Indeed, as far as we know,

r

epeated morph constructions involvi

n

g derivational morphology or compounding

are either tolerated (as in English ex-ex-presiden

t

an

d

Afrikaan

s

b

oon-tjie-tjie ‘

be

an-

D

IM

-

DIM

’

) or avoided (as in English

*

uglil

y

an

d

D

u

t

c

h

*

kop

-

je-je

-

‘cup-

D

IM

-

DIM

’)

,

but they never involve suppletion. (Strictly

speaking, we could expect to find cases

y

o

f coalescence with lexical mor

p

hemes, but in order to test this one has to find

sequences of semanticall

y

different but phonolo

g

icall

y

identical derivational affixes

t

hat are in principle grammatical. We have not been able to do so.

)

W

ithin a single language, not every repeated mor

p

h context will be dealt with in

t

he same way (as will be clear from the English data mentioned in the discussion

above). One might hope that this variation is partially due to the fact that lexical and

functional morphemes will behave differently in repeated morph contexts, as

j

ust

explained. In the worst case, the Parse and Faithfulness constraints mi

g

ht have to be

split into more specific constraints that mention subcate

g

ories of features, o

r

i

ndividual features in some extreme cases. It would take us too far afield to explore

t

his issue here (but see below for more discussion on splitting constraints in this

way).

2.3

M

a

r

kedness

W

e now turn to another type of competition between a null form and an overt

r

ealization of an affix. In the relevant cases, the opposition between the two forms is

u

sed to mark certain properties of the s

y

ntax, in particular the markedness of

particular phi-features in an ob

j

ect and

/

o

r sub

j

ect. The phenomenon can be observed

with both case and agreement.

Th

e

r

e

i

s

a

subs

tanti

ve

lit

e

rat

u

r

eo

n

w

hat counts as a marked subject o

r

o

bject. In a seminal paper, Silverstein (1976) argues for a universal markedness

h

ierarchy along the following lines:

(12) 1 > 2 > 3/proper noun > 3/human > 3/animate > 3/inanimate

A

subject

is

t

more

marked the lower its properties

o

n this hierarch

y

. For example,

any third person subject is more marked than a second or first person subject. In

W

OR

D

-

F

ORMATION IN OPTIMALITY THEORY

295

c

ontrast, the lower the properties of an objec

t

,

the

less

marked it is. Thus

,

a second

person ob

j

ect is more marked than any third person one.

I

n some languages, morphological case is s

e

n

sitive to the status of the sub

j

ect or

o

b

j

ect with respect to the markedness hiera

r

c

h

y

in (12). In particular, overt cases

seem to be preferred for more marked ar

g

uments. In an a

b

s

olutive-er

g

ative case

s

y

stem, er

g

ative tends to be overt; in a

n

ominative-accusative case s

y

stem it is the

o

bject case, accusative, that tends to be

o

vert. In certain split case systems, then,

m

arked subjects distinguish themselves from unmarked ones by carrying ergative

c

ase (rather than nominative, which does not show up morphologically). Similarly,

m

arked ob

j

ects carry accusative (rathe

r

t

han absolutive, which again has no

m

orphological correlate). The answer to the question of what kind of sub

j

ect is

m

arked enough to warrant ergative case m

a

r

king differs from language to language,

as does the cut-off point for accusative markin

g

on ob

j

ects.

This variation amon

g

st lan

g

ua

g

es with a

s

plit-case s

y

stem can be anal

y

zed as

i

nvolvin

g

competin

g

forms, one of which is selected on the basis of a set of

c

onflicting constraints – as in OT-grammar, that is. A proposal along these lines is

d

eveloped by Aissen (1999), who translates Silverstein’s hierarchy into a set of

c

onstraints that require overt case marking for particular types of arguments. The

mo

r

e

mark

ed

a f

e

at

u

r

eco

m

b

inati

o

n f

o

r a particular type of argument, the more

prominent the constraint requiring overt case for this argument. Thus, the following

t

wo constraint hierarchies obtain

(

where CM stands for ‘case mark’

):

6

(13) a. CM [Sub

j

, 3/inanimate] > CM [Sub

j

, 3/animate] > CM [Sub

j

,

3/human] > CM [Subj, 3/proper noun] > CM [Subj, 2] > CM

[

Subj, 1]

b. CM [Obj, 1] > CM [Obj, 2] > CM [Obj, 3/proper noun] > CM

[

Ob

j

, 3/human] > CM [Ob

j

, 3/animate] > CM [Ob

j

, 3/inanimate]

C

rucially, it must be assumed that the con

s

traints in

(

13

)

cannot be reranked with

r

espect to each other, which

w

ould

g

ive rise to lan

g

ua

g

e-particular rankin

g

s of them,

since the essence of Silverstein’s markedn

e

ss hierarch

y

is that it is universal. The

c

onstraints can be reranked, however, with respect to a constraint that militates

against the morphological realization of case. To this end, Aissen adopts a very

general constraint that penalizes structure (*Struc). The position of *Struc in the

co

n

s

traint hi

e

rar

c

hi

es de

t

e

rmin

es

th

ecu

t

-off

p

oint between case-marked and case-

l

ess sub

j

ects and between case-marked and case-less ob

j

ects.

Note that in this system the marki

n

g of case for sub

j

ects and ob

j

ects is in

principle independent. That is to say, the ordering of the constraints in the hierarchy

i

n (13a) with respect to the constraints in the hierarch

y

in (13b) has no effects. This

i

ndependence means that the s

y

stem ma

yg

i

v

e rise to sentences with an Er

g

ative-

A

ccusative case pattern, namely when both

t

he subject and the object classify as

m

arked (the respective CM constraints mentioning their features both being ranked

6

We simplify the details of Aissen’s proposal somewhat. She generates the constraints in (13) using a

t

echnique called

l

ocal con

j

unction (due to Smolensk

y

1995). This does not affect the ar

g

umentation

he

r

e.

296

PETER A

C

KEMA

&

A

D NEELEMAN

above *Struc). Languages with such patterns do indeed occur (see for instance

W

oolford 1997), but there are also languages in which such a case pattern seems to

be disfavoured. Let us assume that there is a constraint which has the effect that only

o

ne argument in a transitive clause can be case-marked (OneCase). If such

a

c

onstraint is sufficiently highly ranked, c

o

nflicts arise in case the sub

j

ect and the

o

b

j

ect both have properties that would normally require case marking. In that case,

t

he mutual rankin

g

of the ob

j

ect and sub

j

ect constraints becomes crucial. Suppose,

for example, that the followin

g

rankin

g

obtains:

(14) One-Case > CM[Obj, 3/human] > CM[Subj, 3/animate] > *Struc >

C

M[Obj, 3/animate] > CM[Subj, 3/human]

Given this constraint ranking, a third person animate sub

j

ect will usually contrast

with a third person human sub

j

ect in being case-marked. However, when a third

person human ob

j

ect is also present, this will require case marking as well, and

g

iven that CM[Ob

j

, 3/human] outranks CM[Sub

j

, 3/animate] while both are

dominated b

y

OneCase, this precl

u

des case markin

g

of the sub

j

ect.

Further research is required to explo

r

e whether there are case s

y

stems that

display these kinds of interactions. However, Trommer (2004) discusses an example

o

f an agreement system in which subjects and objects compete for a single

agreement slot on the verb in this way. The language in question, Dumi, favours

agreement with arguments that have features that are higher on the following two

h

i

e

rar

c

hi

es:

(

15

)

a. 1 > 2 > 3

b. Plural > dual > sin

g

ular

Dumi does not seem to care whether agree

m

e

nt is with the ob

j

ect or the subject,

although object agreement in certain circumstances re

q

uires that an additional

m

arker be added (glossed as MS for ‘ma

r

k

ed scenario’). The effects of the person

h

ierarchy in (15a) are illustrated in (16). The example in (16a) shows that a first

person dual sub

j

ect beats a second pers

o

n dual ob

j

ect in the competition fo

r

a

g

reement, where as (16b) shows that a first person dual ob

j

ect beats a second

person dual sub

j

ect.

(

16

)

a. du:khuts-i

see

-

1.

DUA

L

‘We (dual) saw you (dual)’

b.

a-

du:

kh

u

t

s

-i

MS

-see-1.

S

S

DUA

L

‘You

(

dual

)

saw us

(

dual

)

The exam

p

les in

(

17

)

illustrate the work

i

n

g

s of the number hierarch

y

in (15b).

Irrespective of grammatical function, a plu

r

al argument beats a dual argument in the

battle for agreement.

W

OR

D

-

F

ORMATION IN OPTIMALITY THEORY

29

7

(

17

)

a. do:khot-t-ini

see-

NONPAST

-3

T

T

PL

They (plural) see them (dual)’

b. do:

kh

o

t-t-ini

see-

NONPAST

-3

T

T

PL

‘The

y

(dual) see them (plural)

A

situation can occur in which one argument qualifies better for agreement on

o

ne hierarch

y

, while the other is to be preferred on the basis of the other hierarch

y

,

for example if one ar

g

ument is first sin

g

ular, while the other is third plural. We

m

i

g

ht expect that in such circumstances either the person hierarch

y

outranks the

number hierarchy, or vice versa. However, as Trommer notes, the situation is more

c

om

p

lex.

F

or a start, it often depends on the exact feature content of the arguments which

h

ierarchy carries the most weight. In the case of a second person singular subject

and an object that is third person dual or plural, it is the number hierarchy that

prevails: agreement is with the object. On the other hand, if one argument is second

person dual and the other third person plural, it the person hierarch

y

that is decisive:

t

he chosen a

g

reement marker is specified as second person dual. There is a wa

y

in

which this pattern can be described usin

g

t

he kind of constraints proposed b

y

Aissen

(see above). The idea would be to formulate a separate agreement-demanding

c

onstraint for every possible combination

o

f

p

erson and number features, and to rank

all these constraints in the appropriate order under the constraint that rules out

double agreement (call it OneAgr).

Trommer shows, however, that there is a phenomenon in Dumi that excludes

such an account. As it turns out, there is one case in which conflictin

g

demands

arisin

g

from the person and number hierarchies are reconciled b

y

havin

g

more than

o

ne a

g

reement marker after all. The crucial example involves a first person sin

g

ula

r

argument and an argument specified as sec

o

nd or third

p

erson and as dual or

p

lural:

(

18

)

a. do:khot-t-e-ni

see-

NONPAST

-1

T

T

SG

-

3

PL

‘I see them

(p

lural

)

’

b.

a-

du:

kh

us

-t-

e

-ni

MS

-see-

S

S

NONPAST

-1

T

T

SG

-

3

PL

‘They (plural) see me’

This situation cannot be described in terms of reranking OneAgr with respect to

c

onstraints that require the spell-out o

f

certain feature combinations. One might

f

t

hink that (18) can be accounted for b

y

r

ankin

g

both R(ealize)[1s

g

] and R[3pl] above

O

neA

g

r. This will lead to a rankin

g

paradox, however

,

since there are contexts in

w

hich at least third person plural does not

g

ive rise to a

g

reement, apparentl

y

as a

c

onsequence of OneAgr. In particular, con

s

i

der the situation in which a third

p

erson

plural argument competes with a second person dual argument. As noted above,

t

here is only one agreement marker in this case, for the second person argument.

298

PETER A

C

KEMA

&

A

D NEELEMAN

This implies that R[3pl] must be ranked below OneAgr, in direct contradiction to the

i

nitial suggestion.

Trommer shows that the agreement patter

n

s of Dumi can be captured by an OT-

analysis, but that they require context-sensitive constraints of the type “Realize

agreement

f

or

f

eature F

1

in the presence of F

2

F

”

(

where

F

1

is more prominent than

F

2

o

n the same markedness hierarchy). Ranking

s

uch constraints (with respect to each

o

ther and with respect to a constraint like OneA

g

r) does

g

ive rise to a consistent

g

rammar for Dumi. We refer to Trommer’s wo

r

k for details

,

but it is not difficult to

see wh

y

this works: (18) indicates that both ‘Realize 1 in the

p

resence of 3’ and

‘Realize plural in the presence of singular’ are ranked above OneAgr. The

su

pp

ression of

3

rd

plural in the presence of second person dual indicates that the

d

grammar must also have a partial constraint ranking such that ‘Realize plural in the

presence of dual’ is ranked below both ‘Realize 2 in the presence of 3’ and OneAgr.

These two partial constraint rankings can be combined into a single ranking without

t

his leading to a ranking paradox.

3.

CO

MPETITI

O

N BET

W

EEN

CO

MP

O

NENT

S

3

.1 E

lsewhe

r

ecases

A

s we have seen

,

the basic case o

f

competition in morphology can be

f

c

haracterized by the Elsewher

e

Principle: a more specifi

c

form is preferred over a

m

ore general one where both are in principle grammatical. By definition,

c

ompetitors are those forms that can be used to express the same concepts. It is

possible, therefore, that competin

g

structures are

g

enerated in different components,

i

n particular morpholo

gy

and s

y

ntax.

A

well-known example involves the En

g

lish comparative affix -

er

,

which must

attach to short (maximally bisyllabic) ad

j

ectives (see (19a,b)). This morpheme is in

c

ompetition with the syntactic modifie

r

mo

r

e

,

which can in principle attach to both

s

hort and long ad

j

ectives, and is therefore

t

he more general form. In the context of

s

hort adjectives, the Elsewhe

r

e

Principle dictates that -

er

blocks

r

more

(

see

(

19c,d

))

.

(

We add

(

19e

)

to show that in circumsta

n

c

es where the Elsewhere Principle does not

apply

more

can indeed modify short adjectives.)

(

19) a. Bi

gg

e

r

b. *Intelli

g

ente

r

c. *More big

d. More intelligent

e. Bigger means ‘more big’

T

his classical application of the Els

e

where Principle demonstrates that a

m

orphological complex can be in competition with a syntactic phrase. However, the

effects of the Elsewhere Principle are not limited to morpholo

gy

blockin

g

s

y

ntax. As

W

ORD

-

FORMATION IN OPTIMALITY THEORY

299

(

Chomsky 1995) can be seen as an insta

n

c

e of blocking. Because a lower landing

s

it

ec

an attra

c

t a

subse

t

o

f th

ee

l

e

m

e

nt

s

that a higher landing site can attract, it is, in

t

his sense, more specific than the higher one. Consequently, movement to a higher

l

andin

g

site is blocked where movement to the lower landin

g

site is possible. More

r

elevant in the present discussion are cases in which, as opposed to the one in (19),

t

he specific form is s

y

ntactic and the

g

eneral form morpholo

g

ical

.

The En

g

lish

s

imple past, for instance, is morphological. Yet, in the perfect, it is blocked by a

s

yntactic periphrastic construction, which is more specific as it roughly expresses

p

ast with

p

resent relevance.

A

nother case of competition in which a more specific syntactic construction

blocks a more general morphological for

m

c

oncerns the negated form of the first

person singular of the verb

to be

,

as discussed by Bresnan

(

1999

)(

the account below

i

s somewhat simplified and involves a sli

g

htl

y

different interpretation of the data as

c

ompared to Bresnan’s account). Normall

y

, a sentence with a finite form of

to be

c

an be ne

g

ated b

y

morpholo

g

ical means, namel

y

b

y

addin

g

n’t

to the verb (see

t

Z

wicky & Pullum 1983 for arguments that

n’t

is an affix). There is a gap in the

t

paradigm of these negative forms, however:

n’t

cannot be added to first person

t

s

ingula

r

am

:

I

f the Elsewhere Principle could only compare morphological forms, we may

expect that, given the abs

e

nce of the s

p

ecific for

m

amn

’

t

, the more general for

m

a

r

en

’

t

is used. In inversion contexts, this is indeed the form that occurs:

t

(21) a. *Amn’t I working

b. Aren’t I working

It is important to realize that, in addition to the forms in (20) and (21), En

g

lish

allows a s

y

ntactic realization of ne

g

ation that

is

compatible with (a

)

m

:

(

22) I’m not working

This syntactic combination of

am

an

d

not

expresses the concept “negation of the

t

first person singular of

be

” more accurately than the more general

a

r

en’t

,

and will

h

ence block the latter if the Elsewhere Principle applies across components. We see

t

his happenin

g

in sentences without inversion: (23) is blocked b

y

(22).

(23) *I aren’t working

The question, then, is why inversion should have an effect on the realization of

t

he negated first person of

be

.

Since inversion is an operation of head movement

(Aux-to-C movement), it must strand nonaffixal negation. This rules out (24a) (in

OT terms, GEN cannot generate (24a),

he

n

ce

thi

sw

ill n

eve

r

be

a

c

an

d

i

d

at

e

(

20) a. *I amn’t workin

g

d. we aren’t workin

g

b.

y

ou aren’t workin

g

e.

y

ou aren’t workin

g

c. s/he isn’t workin

g

f. the

y

aren’t workin

g