?tekauer Pavol, Lieber Rochelle. Handbook of Word-Formation

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

C

OGNITIVE APPROACH TO WOR

D

-

FORMATION

239

phonological structure, which is the set

o

f cognitive routines for producing and

perceiving the sound associated with that meaning

.

6

Together the meaning and the

phonological structure make up a symbolic structure, in these cases, a word.

These dia

g

rams are easil

y

interpretable via a ver

y

widespread metaphor which

c

onceives of words (lexical items) as boxes or containers, and their meanin

g

s as

c

ontents (Redd

y

1979). It is better, however, to think of the rectan

g

les (a., b., etc.)

l

inked to the phonolo

g

ical forms ([

æ

"

pl

B

z

]

,

[

o

"

rn

B

d

<

d

z

], etc.

)

, not as boxes but as

w

indows, each habitually opening upon pronunc

i

ati

o

n

o

f th

esou

n

d

a

ssoc

iat

ed w

ith

i

t, and affording a view of, or access to, a pa

r

ticular part of the store of conventional

k

nowled

g

e (cf. Moore & Carlin

g

1982). One advanta

g

e of takin

g

them so is that the

i

dea of enc

y

clopedic meanin

g

fits better. The meanin

g

is what

y

ou can see throu

g

h

t

he window, and that may include details at a considerable distance. The fact that

t

here are too many such details to fit into a small box is irrelevant.

One of the things that can be seen through the window is neighboring concepts

w

hich may have their own labeled windows; thus the overlap of meaning between

c

losely related words is expected rather than in any way problematical. It is, on this

v

iew, part of the meanings of apple

,

orange

,

and

r

aspberr

y

,

part of the store of

c

onventional knowled

g

e that each makes acc

e

s

sible

,

that the fruit each of the

m

d

esi

g

nates (and not, for instance, the fruit named b

y

wate

r

melon

) is commonl

y

made

i

nto a

p

aste-like substance which

p

eo

p

le s

p

read on bread to eat. It is also

p

art of the

k

nowledge accessed by a

pp

le that that

subs

tan

ce

i

sc

all

ed

butte

r

,

whereas fo

r

orange

i

t i

s

ma

r

malade

,

and fo

r

r

aspberr

y

e

ith

er

jam

o

r jell

y

.

The connections may wor

k

both ways, and be stronger one way than another:

ma

r

malade

i

sco

nn

ec

t

ed

t

o

orange

(

s

) more strongly than

orange

(

s

)

to

ma

r

malade

,

but

butter

is not connected to

r

appl

e

so strongly as apple t

o

butte

r

.

Not exactly the same thing, but closely related

t

o it

,

is the fact that these words provide access to the constructions

a

pple butter

,

oran

g

e marmalad

e

,

and

r

aspberr

yj

am

,

respectivel

y

. This seems at best paradoxical

and at worst senseless if

y

ou are thinkin

g

via the container metaphor: it is like sa

y

in

g

a small box contains a bi

gg

er box that contains it. But is much more reasonable if

you think of accessing knowledge through a window. It is like saying that you can

c

limb through the window and see a house of which the window is a part.

2

.5 Sanction

Reco

g

nizin

g

an established sch

e

m

a in a co

g

nitive structure

sanctions

or

l

e

g

itimizes that structure. This makes sense: when we see that somethin

g

fits a

pattern we alread

y

know, we reco

g

nize it, and know what ‘kind’ of thin

g

it is.

Sanction varies in strengt

h according to (a) how well established or cognitively

t

prominent the sanctioning schema is, (b) how close the relationship comes to full

s

chematicity, and (c) how ‘close’ the schema is to the structure in question. A close

s

chema specifies more details of the s

a

n

ctioned structure, whereas a relatively

distant schema despecifies more of them.

6

Although phonology is prototypical, the CG d

e

finitions easily accommodate other kinds of

s

ignifiants

,

s

uch as manual or facial si

g

ns or writin

g

.

240

DA

V

ID T

UGG

Y

Su

pp

ose a

p

erson has a schema fo

r

A

PPLES

(

1.a

)

, and encounters some a

pp

les of

a variety new to him or her, e.g. Criterion

s

. He or she can readily place them in his

o

r her cognitive system, since they are str

o

ngly sanctioned, (b) fu

l

ly and (c) closely,

by the (a) well-established

APPLES. This strong sanction would make it relatively

easy for the new concept to become esta

b

l

ished as a unit

,

and to be used in

c

ommunication, starting the process of conventionalization. Someone who had no

experience of apples would doubtless reco

g

nize the Criterions as

F

R

U

IT

(

1.d

)

, but the

s

anction would be lesser because

(

c

)

the sch

e

m

a is more distant. He or she mi

g

ht

t

hink

o

f th

e

m a

s

a kin

do

f

O

RAN

G

E

S

,

but here the sanction would be reduced

c

onsiderably because (b) the sanction i

s

not full but only partial. Sanction fro

m

B

ANANA

S

would be (b) much less nearly full. For someone who had in his or he

r

c

ognitive system no concept of fruit of any kind, the concept of the Criterions would

be hard to fit into the system at all.

Sanction can be recognized for established as well as new structures. The

established structure is legitimately a part of the system in its own right, but the

s

anction it receives makes it even more stron

g

l

y

le

g

itimate and more clearl

y

i

nte

g

rated into the c

og

nitive/lin

g

uistic s

y

stem. Thus the concept of

A

PPLE

S

,

established as it is for most En

g

lish speak

e

rs, is further sanctioned because it full

y

and closely elaborates the schema

F

R

U

I

T

. In fact

,

establishment itself

,

or unit status

(

section 1), is usefully seen as self-san

c

tion, a limiting case of sanction where the

c

riteria of closeness and fullness

(

b and

c)

are at their maximum and the sanction

v

aries only according to the prominence

o

r

e

ntr

e

n

c

hm

e

nt

o

f th

es

tr

uc

t

u

r

e.

3.

SC

HEMA

S

F

O

R

WO

RD F

O

RMATI

O

N

3

.1 Schemas for words

W

ords, we have claimed, are symbolic

s

tructures, combining a meaning structure

with a phonological structure. Schemas fo

r

words will have the same bipola

r

s

ymbolic character.

W

hat would a schema for words denoting a fruit look like? The semantic poles

(

i.e. the meanings) of such words can be a

r

ranged in a hierarchy like that in Figure 1,

but what of their phonological poles? What does [

æ

"

pl

B

z

]

have in common with

[

o

"

rn

B

d

<

d

d

z

]

and

[

b

næ

"

n

z

]

and

[

ræ

"

zbe

riz

]

and

[

f

ru

t

]

? The

p

ersistent final [

z

]

or

[

z

]

,

w

hi

c

h

c

haracterizes all but

[

fr

ut

]

is of course linked to the idea of plurality, and will

be

discussed later (in section 3.2). Concentratin

g

on the non-plural forms (

[

æ

"

pl

B

]

[

o

"

rn

B

d

<

dd

]

[

b

næ

"

n

][

ræ

"

zbe

r

i

]

and

[

f

rut

]

), we would have to sa

y

that the number of

s

yllables, the

c

onstitution of those s

y

llables, and so forth, are not ver

y

much alike.

What they have i

n

c

ommon seems to be mainly the fact that there is a phonological

COG

NITI

V

E APPR

O

A

C

H T

OWO

R

D

-

F

O

RMATI

O

N

241

th

esc

h

e

ma f

o

r a ‘fr

u

it n

ou

n’

w

ill ha

ve

a

s

it

s

semantic

p

ole the

c

once

p

t of a fruit but

i

ts phonolo

g

ical pole will onl

y

specif

y

“some phonolo

g

ical

s

tr

uc

t

u

r

e

”

.

Thi

ssc

h

e

ma

i

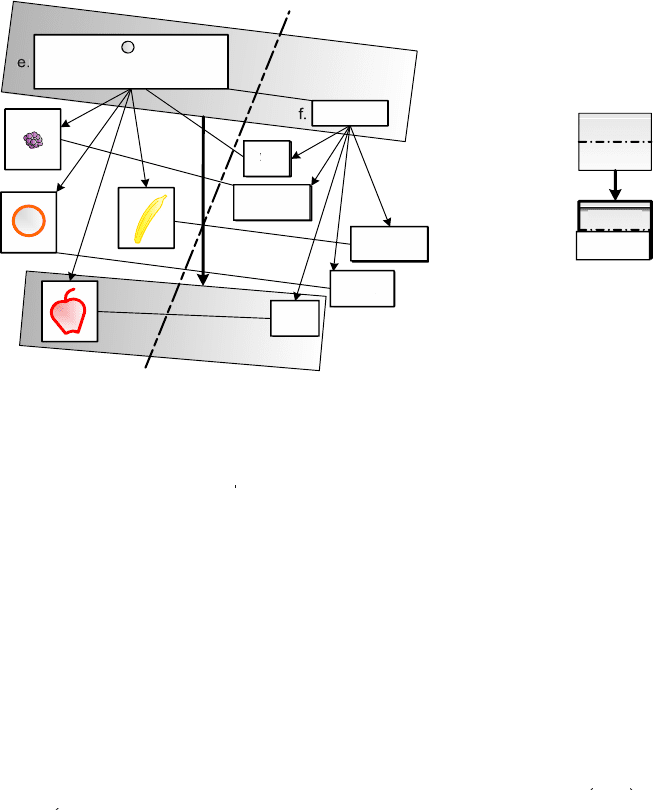

s represented as Figure 2.g, the symbolic union of 2.e-f. Its

globally schematic

r

elationship to appl

e

(2.i) requires that both its semantic and its

phonological

s

tr

uc

t

u

r

es be sc

h

e

mati

c

f

or

apple’s. (The globally schematic

relationships to

r

aspberr

y

,

banana

,

etc., are not represented in the diagram fo

r

s

implicity’s sake.)

2.g is not the word frui

t

(

2.e-h

).

Fr

uit

has a specific phonological structure [

t

f

r

ut

]

,

which is not schematic for

[

æ

"

p

B

pp

l

]

and the rest. Thus

fruit

as a whole cannot be

t

sc

h

e

mati

c

f

or

apple and the other fruit nouns as wholes, although its semantic pole

(

2.e, c

p

. 1.d

)

9

is schematic for theirs. 2.

g

shares

f

rui

t

’

sse

manti

cs

tr

uc

t

u

r

ebu

t it

s

phonolo

g

ical structure is schematic fo

r

f

rui

t

’

s

(

as well as for those of a

pp

l

e

an

d

th

e

r

est

)

, and

fruit

as a whole elaborates 2.g.

t

On the right side of Figure 2 is an abbreviated kind of representation fo

r

structures like 2.g and 2.i, the word a

pp

le

,

which we will use in most following

d

iagrams: the semantic structure is represented in the top half of a box and the

7

For English schemas the unspecified phonological mat

e

r

ial may be expected to consist of English

sounds (phonemes). Even the maximall

y

schematic phonolo

g

ical schemas we discuss in the rest o

f

t

his article are specific in that wa

y

.

8

One might, from these four examples (and most others), include a specification of two or three syllables,

t

he last being unaccented. This would ultimately hav

e

to be a preferential-type specification (which

fits fine with categorization by pr

o

totype), given the existence of

[

pit

5

tt

]

‘peach’,

[

bo

ys

nbe

ri

]

,

[

marakuya

] and other forms that contradict these specifications.

9

Actually the word fruit

has in its semantic structure the plural/mass schema of Figure 1.d as well as the

t

s

in

g

ular conception of 2.e.

frut

...

G

rows on tree, bush, vine , detachable,

t

y

picall

yj

uic

y

& edible, Etc

.

.

g.

h.

rǙzbèri

bԥnǙnԥ

órnˆd

Ǚmiˆ

i.

FRUIT

FRUIT

FRUIT

FRUIT

FRUIT

FRUIT

...

g.

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

i.

Ǚmiˆ

Phonolo

g

ical

S

tructures

S

emantic

S

tructure

s

Fi

g

ure 2 Fruit words: a bipolar schema

3"

R

N

B

Q"

T

PBF

<

F

3

"

R

NB

D

P3

"

P

T

3"\

D

G

º

T

K

H

T

H

H

W

V

p

ole

.

7

,

8

Accordingly,

2

4

2 DA

V

ID T

UGG

Y

c

orresponding phonological structure in the bottom half. It should be remembere

d

t

hat an arrow of full schematicity between

t

wo such bi

p

artite boxes means that there

are relationships of schematicity (or of its limiting case, identity) between the two

semantic structures and also between the two phonological structures.

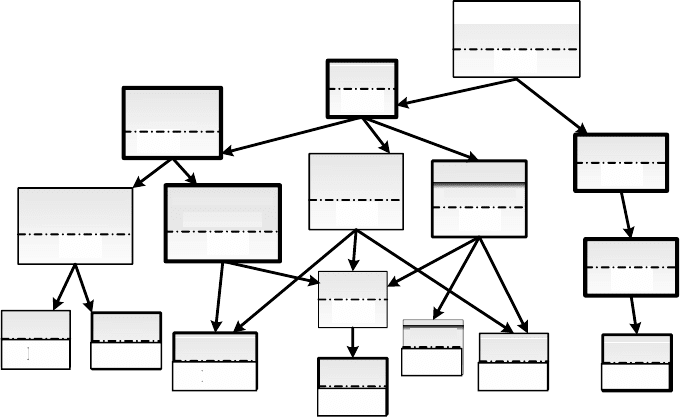

Schemas like 2.g can be arranged in hierarchies, and the schemas near the tops of

t

hose hierarchies are often particularly important for stating grammatical

r

e

g

ularities. 2.

g

and 2.i are represented in Fi

g

ure 3.

g

and 3.i as part of such a

h

ierarch

y

. 3.

j

, k, and l are schemas for three different patterns which 3.

g

elaborates.

The class of Thin

g

s bounded in space (defined b

y

schema 3.

j

) is a particularl

y

salient or prototypical one (it comprises what are sometimes called physical objects),

but it has much in common with Things bounded in other domains, which gives rise

t

o a more schematic notion of bounded Things (3.m). 3.n is a higher schema over all

o

f these, which specifies that its semantic structure designates a Thing. This is a

t

echnical term in CG, a structure roughly equivalent in its meaning to that of

thing

in

g

t

he phrase anything at all

.

3.n’s phonological pole, like those of 3.g,

j

, k, and l,

simpl

y

specifies ‘some phonolo

g

ical structure’. This schema defines, in CG, what a

n

oun

(

or other nominal structure

)

is; its subcases define subclasses of nouns.

(

3.l,

m

and n will show up as parts of constructional schemas in 4.u, 6.aa-a

g

, and Fi

g

ures 7-

8) A similar schema, except for specifyi

n

g a Process (again a technical ter

m

d

enoting a relationship evolving through conceived time) as its semantic pole,

d

efines the class of verbs

(

and verbal stru

c

tures) (3.o), including as a typical case

actions (3.p) such as

eat

(3.q) but other types as well. Other similar bipolar symbolic

t

s

chemas define the other ‘ma

j

or grammati

c

al classes’ or ‘parts of speech’ (see

Lan

g

acker 1987: 183-274, 1991b: 59-100 for extensive discussion). The topmost

s

chema, 3.r, is equivalent to the concept

S

YMB

O

LI

CS

TR

UC

T

U

R

E

,

i.e. it is schematic

for all the s

y

mbolic structures of a lan

g

ua

g

e, and its semantic structure, often

re

f

e

rr

ed

t

o

a

s

ENTITY

,

is e

q

uivalent to the conce

p

t

CO

N

C

EPT

,

as it is schematic for all

se

manti

cs

tr

uc

t

u

r

es.

COG

NITI

V

E APPR

O

A

C

H T

OWO

R

D

-

FO

RMATI

O

N 2

43

l

ik

e

appl

e

(

2.i-3.i

)

and

orange

an

d

banana

(in Fi

g

. 2) that prompts the establishment

o

f the FruitN schema (2.

g

-3.

g

), and the

e

xi

s

t

e

n

ce o

f

suc

h

wo

r

ds

an

dsc

h

e

ma

s

a

s

t

h

ose

an

d

flour

and

r

sushi

and dozens of others that

p

rom

p

ts the establishment of the

F

oodN schema (3.l). Similarly, it is the existence of a

pp

l

e

an

d

flower

and

r

stone

an

d

p

iano and hundreds of similar count nouns (among which

sushi

an

d

flour

ar

e

n

o

t

r

i

ncluded) that prompts the establishment of the physical ob

j

ect count noun schema

3.

j

, which in turn supports the establishment of the count noun schema 3.m. 3.m,

3.k, 3.l and man

y

other schemas in turn allow the establishment of the

THIN

G

sc

h

e

ma

3.m. The patterns arise, ultimatel

y

, from specific usa

g

es, and where there are

different usa

g

es the schematic structures will be different. CG disallows patterns

which cannot be supported empirically in this way.

The structures of the network naturally differ in their degrees of prototypicality,

according (largely) to thei

r

frequency of use. Thus a

pp

l

e

is re

p

resented as more

prototypical (prominent and strongly entrenched) than the fruit noun schema (3.g)

and even more so in comparison with

sushi

. 3.k is not as prominent as 3.

j

or 3.l, and

so

f

o

rth

.

10

There is also a kind of ‘top-down’ness about it, in that the ma

j

or

g

rammatical cate

g

ories are held to be

c

losely related to fundamental cognitive abilities (

R

ELATI

O

N to our ability to conceive of entities in

c

onnection with each other

,

THIN

G

to our ability to reify, PR

OC

E

SS

to our ability to scan sequentially,

and so forth; see Langacker 2000: 2-3). This helps explain, for instance, why these categories are

u

biquitous among the world’s languages. But this ki

n

d of ‘top-down’ structure does not negate the

‘bottom-up’ness of the schematic hierarchies that actuall

y

arise in different lan

g

ua

g

es, which are b

y

n

o

m

e

an

s

i

de

nti

c

al

.

THING

THING

THING

THING

THING

G

...

n.

THING b d

THING bound

THING bound

-

THING bound

ed in space

ed in space

ed in space

ed in space

ed in space

p

...

l.

THING

THING

THING

THING

people eat

people eat

people eat

people eat

people eat

pp

...

j.

FRUIT

FRUIT

FRUIT

FRUIT

FRUIT

FRUIT

...

g.

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

i.

Ǚmiˆ

SUSHI

SUSHI

SUSHI

SUSHI

SUSHI

SUSHI

súi

ENTITY

(= CONCEPT)

(= CONCEPT)

(= CONCEPT)

( CONCEPT)

( CONCEPT)

()

...

r.

PROCESS

PROCESS

PROCESS

PROCESS

PROCESS

PROCESS

...

o.

ACTION

ACTION

ACTION

ACTION

ACTION

CO

...

p.

EAT

EAT

EAT

EAT

EAT

EAT

it

q.

THING

THING

THING

THING

flt

from plants

from plants

from plants

from plants

p

...

k.

FLOUR

FLOUR

FLOUR

FLOUR

FLOUR

FLOUR

flát oˆ

FLOWER

FLOWER

FLOWER

FLOWER

FLOWER

FLOWER

flát oˆ

THING b d

THING bound

THING bound

-

THING bound

ed in time

ed in time

ed in time

ed in time

ed in time

...

DAY

DAY

DAY

DAY

DAY

DAY

de

j

FLASH

FLASH

FLASH

FLASH

FLASH

flæ

bdd

bounded

bounded

bounded

bounded

THING

THING

THING

THING

THING

THING

...

m.

Figure

3

Bipolar schemas for major grammatical classes

The ‘bottom-up’ nature of this network is important

.

1

0

It i

s

th

ee

xi

s

t

e

n

ce o

f

wo

r

ds

H

N3

H

H

5

FG¥

H

N

H

H

C

"Y

C

T

B

3"

R

N

B

U

W

"

5

W

K

HN

C"YTBB

K

V

244

DA

V

ID T

UGG

Y

3.2 Schemas

f

or clearl

y

identi

f

iable word pieces: stems and a

ff

ixes and

const

r

uctional schemas

Many of the phonological structures of our examples have been eithe

r

i

ncommensurate

([

æ

"

pl

B

]

, [

o

"

rn

B

d

<

d

]

and [

b

n

æ

"

n

]

) or identical (the phonological

structures in Fi

g

ure 3.

g

,

j

-p and r, for instance.) In the case of the plural nouns in

F

i

g

ure 1, however, there are more interestin

g

thin

g

s to sa

y

about the phonolo

g

ical

s

tr

uc

t

u

r

e.

[

æ

"

pl

B

z

]

,

[

o

"

rn

B

d

<

d

z

]

,

[

[

b

næ

"

n

z

]

,

[

ræ

"

zbe

r

iz

]

and

[

wa

"

tr

B

m

e

l

n

B

z

]

all have in common a

[

z

]

at the end. A schema […z] would characterize that commonalit

y

. And of course

t

hese are not the only ones: [

wr

B

d

z

]

and

[

ho

rs

z

]

and

[

he

j

e

e

z

]

and

[

sno

"

b

n

l

z

]

and

[

sni

"

i

i

z

z

]

and

[

bro

j

o

o

l

z

]

and thousands of other words can be characterized b

y

that schema.

Man

y

, thou

g

h b

y

no means all, of those thousands of words, includin

g

all the fruit

nouns we were considerin

g

, also have a semantic specification in common: the

y

designate a mass-like Thing consisting of an indefinite number of replications of

some other Thing. Such common cooccurrence naturally gives birth, in people’s

m

inds, to a bipolar schema, in which the phonological pattern […z] is linked

symbolically to the semantic pattern

G

RO

U

P OF REPLICATE THINGS

.

This is a very

i

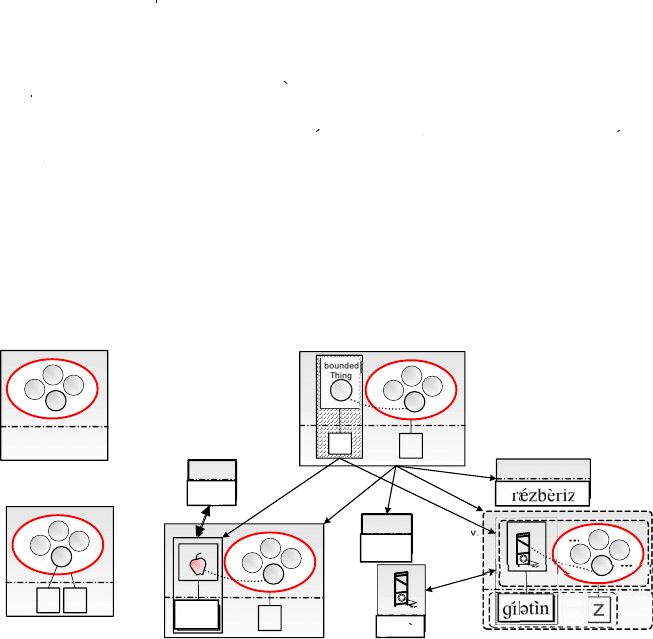

mportant plural noun suffix in English. It is diagrammed in Fig. 4.s.

B

ut there is more to it. The commonalit

y

of these words also includes the fact

t

hat the rest of the phonolo

g

ical structure, the three dots at the be

g

innin

g

of […z], so

t

o speak, is in fact the phonolo

g

ical pole of a structure namin

g

the kind of Thin

g

that

i

s replicated. Thus 4.t, where that linkage

i

s re

p

resented, is a better, because more

c

om

p

lete re

p

resentation. 4.t can also be re

pr

e

sented, for clarity, as in 4.u, where the

r

eplicated Thing’s role as semantic pol

e

of the phonological material preceding the

[z] is separated out from its role in the m

a

s

s of replicates. (The distortion engendered

by this analytical separation is recorded by a dotted ‘line of correspondence’.) This

bipolar schema, whose phonological pole precedes the [z] in 4.u, is in fact the count

noun schema 3.m

,

and so is labeled 4.m.

s.

...

...

…z

t

.

...

...

… z

u.

...

...

z

a.

...

...

ǚmiˆ

z

i.

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

Ǚmiˆ

m.

RASPBERRIES

RASPBERRIES

RASPBERRIES

RASPBERRIES

RASPBERRIES

RASPBERRIES

ǚzbèriz

TABLES

TABLES

TABLES

TABLES

TABLES

TABLES

té

g

_iˆz

w.

gȩʞlԥtìn

z

…

F

igure 4

-

z

‘

plural

‘

’

and Stem

-

z

const

r

uctions

3

"

R

NB

I

+"NVK

I

K

K

P

3

"

R

N

B

V

G

"

D

N

B

\

COG

NITI

V

E APPR

O

A

C

H T

OWO

RD

-

F

O

RMATI

O

N

245

p

lural suffix, it is also a schematic construction, a rule or

p

attern for

p

lural nouns

w

ith -z

.

It

ss

an

c

ti

o

n

o

f a

pp

les (4.a, of which 1.a is an unanal

y

zed version) is

r

epresented in some detail in Fi

g

. 4. Note that the replicated Thin

g

in a

pp

les i

s

s

pecified to be an apple, and its phonolo

g

ical pole is [

æ

"

pl

B

]

.It is our old friend 2.i-3.i

again. Its occurrence as 4.i, outside the apples box to represent its independence

from that construction, is linked to its occurrence inside the box by the double-

h

eaded arrow that reminds us that identity can be viewed as bidirectional

s

chematicity.

4.

m i

sw

hat i

s

t

e

rm

ed

an

elabo

r

ation

-

site

or

e

-

site

.

An

e

-

s

it

e

i

s

a ‘h

o

l

e

’ in

o

n

e

s

tructure that expects to be filled by another structure. In this case, the bipolar ‘hole’

in

-

z

, or (what is the same thing) in the Stem-

z

c

onstruction, is filled by a

pp

l

e

.

Similarly it is filled by

table

in th

ewo

r

d

tables

,

and by

r

aspberr

y

in th

ewo

r

d

r

as

p

berries

,

though the same level of detail is not shown. E-sites are traditionally

m

arked in diagrams by cross-hatching, so 4.m is cross-hatched.

T

ypical e-sites are not fully schematic: i.e. they do not consist of 3.r, but of some

s

chema further down a hierarchy such as Fig. 3. The e-site in 4.u, as we have

m

entioned, can be identified with 3.m. Thus affixes are ‘choosy’, in contrast to

s

tems, which are ‘promiscuous’ (Taylor 2002: 266-268). (Certain kinds of

phenomena, however, such as clitics which always occur in a specified position but

do not particularly care what they occur next to, will have more fully-schematic e-

s

ites.) Nevertheless e-sites are typically quite highly schematic: they come from the

upper reaches of a structure like Fig. 3. A

n

e-site which is highly specific, to the

point of specifying a particular companion structure, is likely to be less than widely

useful. (They do exist, however, e.g.

gruntled

has a strong e-site specifying that it be

d

preceded b

y

dis-

)

.

W

e can now characterize the difference b

e

t

ween stems and affixes. Affixes

,

like

-z

,

have a gaping hole, a salient e-site, strongly associated with them. If the e-site

precedes the affix phonologically, you have a suffix, if the e-site follows you have a

prefix. The e-site resides in a constructional schema with which the affix is

associated; in the t

y

pical case the affix cannot in fact be activated without activatin

g

the whole schema. The e-site is so important, and so schematic, usuall

y

at the

s

emantic pole but especially at the phonological pole, that the pattern cannot be

easily or usefully thought, and cannot be pronounced, unless a specific stem, such as

appl

e

, is drafted into service to elaborate the e-site

(

to fill the hole

)

. Affixes are thus

conceptually dependen

t

,

at both poles, upon the stems they combine with. This

dependence varies in proportion to the salience of the e-site and its schematicity

re

lati

ve

t

o

th

e

f

o

rm

s

that fill it (Langacker 1987: 300).

T

his is a case of the sort described in section 2.4, where upon enterin

g

throu

g

h

the ‘window’ opened b

y

a phonolo

g

i

c

al f

o

rm

we

ar

e

fa

ced w

ith a lar

g

er structure of

which this is a

p

art. The Stem-

z

construction is so closely associated with

z

-

z

as to be

z

i

nvariably activated when it is.

Prototypical stems, in contrast, are conceptually autonomous. Though they are

(

of course) usually used next to some othe

r

symbolic structures, they can be usefully

It is clear

,

if one considers the matter

,

that 4.t-u is schematic for such nouns as

apples

,

tables

,

r

aspberries, etc. In other words, 4.t-u is not only a description of the

246

DA

V

ID T

UGG

Y

h

ave salient e-sites, and are not inevitabl

y

activated as part of some more inclusive

structure. So appl

e

can be, and often is, used without bein

gj

oined to somethin

g

like

-z

,

but

-z

can only be used after a count noun, and that is the basic difference

z

between them. It is not just a matter of different usage, but of different cognitive

s

tr

uc

t

u

r

es

that r

esu

lt fr

o

m tha

t

usage and perpetuate it.

t

A

utonomy and dependence are matters of degree, however, and the distinction

between stems and affixes is accordingly not absolute. Some affixes (e.g.

s

uper

-

,

o

r

half-

)

m

ay occasionally or even fairly com

m

o

nly be used in relatively autonomous

w

ays, and of course doing so lessens thei

rco

nn

ec

ti

o

n t

o

th

e

r

e

l

ev

ant affix-

s

t

em

c

onstructions. Some usuall

y

-independent fo

r

ms ma

y

in special uses be dependent

(e.

g.

over

when used with the meaning ‘m

r

o

re than is desirable’

,

as in

ove

r

eat

,

is

normall

y

prefixal.) Stems can be quite hi

g

hl

y

dependent (e.

g

. the ste

m

dent

-of

dentist

,

dental

,

dentition

an

d

dentifric

e

,

or the ste

m

gruntled

,

mentioned above

)

, and

o

nly recognizable as stems because they ar

e

less de

p

endent than the affixes with

w

hich they join. In many languages dependent stems are the norm: e.g. in Latin

n

oun and ad

j

ective stems need case suffixes, and verb stems need person-tense-

m

ood suffixes. Sometimes strong dependence is so balanced that it makes sense to

speak of affixes

j

oining with eac

h

o

th

e

r in

s

t

e

a

do

f

w

ith

s

t

e

m

s.

11

3

.3 Complex semantic and phonolo

g

ical poles

The semantic and phonolo

g

ical poles of both morphemes and constructions are

o

ften complex cate

g

ories, families of related structures, rather than sin

g

le unitar

y

s

tr

uc

t

u

r

es.

11

This last confi

g

uration is not common in En

g

lish, thou

g

h it is more so in some other lan

g

ua

g

es. The

wo

r

d

r

e-u

p

meaning ‘re-enlist’ approximates it, though the u

p

(

cf.

s

ign up) is not clearly affixal. Fl…

,

s

l…

,

s

n…

,

…i

p

,

…

ap

,

…

o

p

,

and similar ‘sound-symbolic’ formatives,

i

f they are taken as affixal, link

u

p in structures of this sort

(

flip

(

(

,

flap

,

flop

,

s

li

p

,

s

lap

,

s

lop

,

s

nip

,

snap

,

etc.) See Tuggy 1992 for more

detailed discussion of these sorts of

p

heno

m

ena and the stem-affix

g

radation

g

enerall

y

.

t

hought and pronounced without being joined to any other particular kind of

s

tructure, and they can

j

oin with many kinds (they are ‘promiscuous’). They do not

x.

y

.

Red when ripe, eaten raw,

sweet and/or tart, crunchy or

nch

mea

ly

, t

hi

n e

dibl

e

skin -like peel ,

Et

c.

Y

ellow when ripe, eaten raw,

sweet and/or tart, crunchy or

nc

mealy, thin edible

s

kin -like peel ,

E

t

c

.

G

reen when ri

p

e, b ake d in

p

ies

or eaten raw, tart, crunch

y

,

t

hi

n

edible

skin -like

p

eel,

Et

c

.

E

t

c

.

Red, yellow, or green

w

h

en r

i

pe, e

dibl

e

,

t

hi

n

edible ski

n

-

lik

e pee

l

,

E

tc

.

c

f.

1.

a

.

Ǚmiˆ

S

mall

g

reen sour

h

ardl

y

edible

no

t

cu

ltiv

a

t

ed

In

ed

i

b

l

ef

r

u

it

of

r

ose bush

...

...

…

[+vd]

z

…

[+strd]

ԥz

…

[-vd]

s

…

(ԥ)

S

cf

.

4.

s

.

…

(ԥ)

z

Figure

5

Complex semantic and phonological poles

3

"

R

N

B

C

OGNITIVE APPROACH TO WOR

D

-

FORMATION

24

7

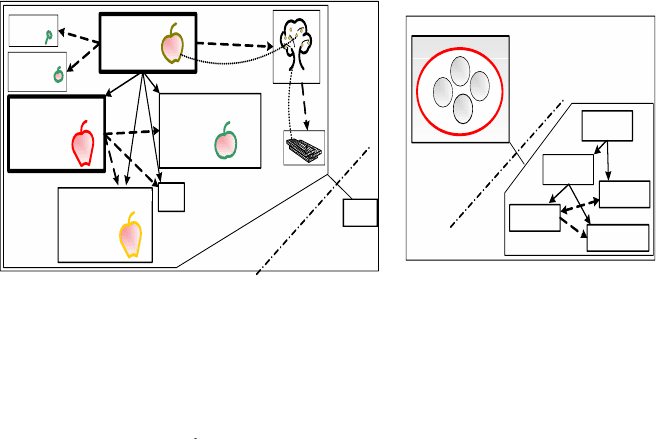

For instance, the meaning

APPLE

,

for many American English speakers, has as its

prototype something like a Red Delicious apple, with its typical red color (when

r

ipe), sweet taste, tallish shape, particular consistency, common usage for eating

r

aw, and so forth. Other kinds of apples

,

such as Grann

y

Smiths, Pippins, Galas,

Rome Beauties, and so forth – which ma

y

be rounder or squatter,

g

reen or

y

ellow o

r

o

f varie

g

ated colors when ripe, tarter and crisper, more commonl

y

used for makin

g

pies or applesauce or cider, etc. – are, however, very good exemplars of the category

as well. Crab a

pp

les and custard a

pp

les a

r

e not very good exemplars, and rose apples

are even less so, to the point where many would deny that they are apples at all. The

g

ood examples generally fall under the schematic characterizations given by most

dictionaries (e.g. Webster’s Seventh New

C

ollegiate: “The fleshy usu. rounded and

r

ed or yellow edible pome fruit of a tree (genus

Malus

) of the rose family.”) It can

easil

y

be seen that if the ‘edible’ specific

a

t

ion is relaxed crab apples can be fit in,

and if the

g

enus specification (with its Latin name which of course is not part of the

m

eanin

g

for man

y

En

g

lish speakers) is relaxed, custard apples can fit in, and if both

are relaxed rose apples fit. An extension from this cluster of meanings allows the

tree on which prototypical apples grow to also be called an apple, and a furthe

r

extension allows wood from such a tree to be called a

pp

le. The whole cluster of

m

eanings, as suggested in Fig. 5.x, cons

t

itutes the semantic pole of the morpheme

appl

e

.

T

he phonological pole of the plural morpheme is similarly complex. The endings

[

-

z

]

,

[

-

z

]

, and

[

-

s

]

are all well-established as varia

n

t

s of each other. A

g

ain, schemas

c

an be extracted representing the com

m

o

nalities among these structures, and the

whole complex (represented in 5.

y

), is the pole of the plural morpheme

.

12

Clearly these kinds of complexity are not

limited to morphemes, as again can be

t

documented easily by consulting a dictionary. The word

constitutional

,

for instance

,

h

as meanings related to foundational documents of organizations but can also mean

a walk undertaken with a view towards improving one’s health. It also has differing

pronunciations as a word alone and as the first element of the word constitutionalit

y

.

Similar complexities can be documente

d

for both the semantic and phonological

poles of more schematic constructions as well.

T

hese kinds of complexity are, on CG’s view, perfectly normal. As a limiting

c

ase, a single cognitive configuration may constitute a semantic or a phonological

pole, but there is no strong pressure for this to be the case. By the very nature o

f

c

omplex categories, it is not always possible to specify how many subcases should

be distinguished (e.g. how many senses constitute the semantic pole of appl

e

)

no

r

h

ow they should be grouped – it depends on the relative saliences of the units, the

densit

y

and saliences of the cate

g

orizin

g

relationships, and the purposes of the

12

Displa

y

s of a schematic hierarch

y

of morphemes with identical semantic or phonolo

g

ical poles should

be considered a notational variant of the type of diagram in Fig. 5. Such a display, corresponding to

5

.y though less complete, may be found in Fig.7.ah and its three subcases.

C

omplex semantic poles are easily documented in the complex entries that any

r

easonably complete dictionary has for most of its words or morphemes. But even

where a dictionary gives one meaning it often covers up considerable complexity.

248

D

A

V

ID T

UGG

Y

3.4 Schemas for compounds

Stems commonly

j

oin together to form compounds, where neither element

depends stron

g

l

y

on the other. As an example, conside

r

apple butter

(6.z). This form

r

i

s established (for man

y

American En

g

lish speakers, at least) in its own ri

g

ht and

thus, b

y

the CG definition (section 1.1), is part of the

g

rammar of En

g

lish. It also

belongs to several extended families of forms, one of which is a family of

c

om

p

ounds whose first element is a

pp

le

(

6.ac and subcases

)

, another of com

p

ounds

ending in

butter

(6.ae and subcases), and one of FoodN-FoodN compounds (6.ad

r

and subcases

)

. Othe

r

appl

e

-

N compounds would include apple jell

y

,

applejac

k

,

apple cider

,

apple blossom

,

apple orchard

,

and so forth.

1

3

Clearly some of these are

m

ore closely related than others to apple butter

,

and a schematic network can easily

express those relationships, e.

g

. b

y

schemas such as 6.aa. Other N-

butter

compounds

r

wou

l

dbe

cocoa butte

r

,

g

arlic butter

,

h

one

y

-butter

,

peanut butter

,

and others. Since

cocoa butter

is (for many Americans, at least)

r

primaril

y

an in

g

redient in skin care

products and only secondarily, if at all, an edible commodity, it is represented as an

extension rather than an elaboration

(

subcase

)

of 6.ab.

Ne

ith

e

r th

e

a

pp

le

-

N schema

(

6.ac

)

nor the N-

butter

schema (6.ae) is likely to be

r

particularly well-entrenched. There are not that many compounds subsumed unde

r

either pattern, nor are they particularly common. The more-specific apple

-

F

ood

an

d

F

ood

-

butter

schemas (6.aa and 6.ab) include the

r

m

a

j

ority of the specific forms, and

their sanction is therefore likel

y

to be more important fo

r

f

o

rm

s

lik

e

apple butte

r

(by

r

principle (c) of section 2.5). Furthermore, the connection between appl

e

an

d

th

e

a

pp

l

e

-

N

p

atterns, and between

butter

and the N-

r

butter

patterns, are not very strong.

r

App

l

e

an

d

butter

can easily be, and often are, activated without activating the

r

c

ompounding patterns. This is in direct contrast with the N

-z

pattern (4.u) which is

z

well-entrenched itself

,

and which

i

s inevitably activat

ed w

h

e

n

ever

-

z

is activated.

z

T

hus

,

while the appl

e

-

N an

d

N-

butter

patterns can rightly be thought of (and are

r

r

epresented in Figure 6) as providing e-sites for the construction, the degree of

dependence throu

g

h those e-sites is minimal.

A

ppl

e

an

d

butter

remain stems and not

r

affix

es.

T

hese schemas are themselves sub

j

ect to f

u

rth

e

r

sc

h

e

matizati

o

n

.

6

.

aa an

d

6

.

a

b

are subcases of 6.ad, the relatively well-entrenched FoodN-FoodN schema, which

i

ncludes hundreds of exam

p

les like

b

anana

p

i

e

an

d

s

hrim

p

cocktail

,

and 6.ad in turn

i

s a subcase of the com

p

onent-N schema 6.af, which includes thousands more

1

3

For the question of whether some of these are single words or not

,

see section 4.2. On the CG view

,

it

i

s not a crucial question. The differences in accentuation can be made definitional for the question if

o

ne wants, but it is far from clear that this is

ge

nerall

y

revelator

y

. In other words, nothin

g

prevents a

l

in

g

uist from settin

g

up a schema that specifies a p

r

i

mar

y

stress on the first stem and a secondar

y

o

r

n

o stress on the second stem, and callin

g

it b

y

the

n

ame ‘compound’; but that would not den

y

the

i

mportant

g

eneralities represented in Fi

g

ure 6 which i

g

nore that specification.

analyst. “The definition allows a single network to be divided into lexical items in

m

ultiple and mutually inconsistent ways. I regard this as a realistic characterization

o

f the phenomena in question.” (Lan

g

acker 1987: 388).