?tekauer Pavol, Lieber Rochelle. Handbook of Word-Formation

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

C

OGNITIVE APPROACH TO WOR

D

-

F

ORMATION

249

6.ad, 6.af and 6.a

g

are noteworth

y

in havi

ng

multiple e-sites, and in fact in bein

g

c

onstituted lar

g

el

y

b

y

those e-sites. These are the analo

g

ues, in CG, of what othe

r

m

odels mi

g

ht call morpholo

g

ical rules. The

y

are even more closel

y

the analo

g

ues of

the constructions of Construction

g

rammar

(

F

illmore et al. 1988; Goldber

g

1995

).

B

ut clearly they differ not in kind, but only in degree of schematicity, fro

m

s

tructures such as 6.aa

,

ab

,

ac and ae

,

whic

h

specify one of their e-sites more fully,

and the

y

in turn differ onl

y

in de

g

ree of schematicit

y

from full

y

specified

c

ompounds like 6.z and the others displa

y

ed in Fi

g

ure 6. Similarl

y

the difference

between somethin

g

like 6.aa-ac or ae and an affixal structure like 4.u is onl

y

a matter

o

f the strength and inevitability of the

c

ognitive connection between the morpheme

i

n question and the construction of which it is a part.

N

ote also the re

p

eated use of schematic structures from Figure 3 as e-sites in

these constructional schemas

(

6.l = 3.l, 6.n = 3.n; also of course 6.i = 3.i

)

. This is

directl

y

parallel to the appearance of 3.m as the e-site of the plural constructional

s

chema 4.u, and is quite typical. It confirms the grammatical utility of such

h

ierarchies as Figure 3.

Finally, note that in all the structures in Figure 6 the second bipolar element (i.e.

the one whose phonological pole follows the other) is represented as schematic fo

r

th

ese

manti

cco

n

s

tr

uc

ti

o

n a

s

a

w

h

o

l

e.

Th

is

i

s

in a

cco

r

d

an

ce w

i

th th

e

fa

c

t

s

that

APPLE

BU

TTE

R

is a kind of

R

EDIBLE PA

S

TE rath

e

r than a kin

do

f

APPLE

,

an APPLE

O

R

C

HAR

D

i

s

a kin

do

f

O

R

C

HARD rath

e

r than a kin

do

f APPLE

,

PAPERB

O

ARD i

s

a kin

do

f

BO

AR

D

examples, such as

paperboard

,

i

r

on ho

r

se

,

cotton shi

r

t

,

etc. 6.af and all other ri

g

ht-

h

eaded N-N compounding patterns, including 6.ac, are subsumed by 6.ag.

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

æmiˆ

m

a

j

or in

g

redient

f

or

dbl thikih

dbl thikih

spreadable thickish

spreadable thickish

sp eadab e t c s

p

dibl PASTE

edible PASTE

edible PASTE

edible PASTE

edible PASTE

bȘʝqoˆ

m

ain ingredi ent for

i.

i.

ˆ

s

ignifi cant i ngr edient of

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

ǚmiˆ

li fl d

garlic flavored

garlic

-

flavored

garlic flavored

g

BUTTER

BUTTER

BUTTER

BUTTER

BUTTER

gárlkbȘʝqoˆ

d bl PASTE

spreadable PASTE

spreadable PASTE

spreadable PASTE

p

df t

made of peanuts

made of peanuts

made of peanuts

made of peanuts

p

pínԥtbȘʝqoˆ

dbl l

spreadable clear

spreadable clear

spreadable clear

p

gelled edible PASTE

gelled edible PASTE

gelled edible PASTE

gelled edible PASTE

g

dèl i

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

ǚmiˆ

main in

g

redient for

i.

l

.

ac

.

ab

.

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

æmiˆ

assoc

i

a

t

ed

wit

h

n.

i.

l ORCHARD

apple ORCHARD

apple ORCHARD

apple ORCHARD

apple ORCHARD

pp

ǚmiˆ¬r t oˆd

s

i

g

nificant i n

g

redient of

bfSTEW

beef STEW

beef STEW

beef STEW

beef STEW

bíf st ú

dbl

spreadable

spreadable

spreadable

p

thickish PASTE

thickish PASTE

thickish PASTE

thickish PASTE

bȘʝqoˆ

s

i

g

nificant i n

g

redient o

f

n

.

PASTE from

PASTE from

PASTE from

b

cocoa beans

cocoa beans

cocoa beans

cocoa beans

kókobȘʝqo ˆ

z.

ae

.

ad

.

n.n.

associa

t

ed

w

i

t

h

ag

.

aa

.

THING

pp

people eat

…

…

THING

p

people ea

…

…

+ʞ

T

HIN

G

…

THIN

G

…

THIN

G

…

THIN

G

…

+ʞ

s

i

g

ni

f

icant in

g

redient

/

com ponent o

f

af

.

n.

THING

…

THING

…

BOARD made of

BOARD made of

BOARD made of

BOARD made of

paper

paper

paper

paper

pé

g

moˆbòrd

apple PIE

apple PIE

apple PIE

apple PIE

pp

ʝmiˆpáj

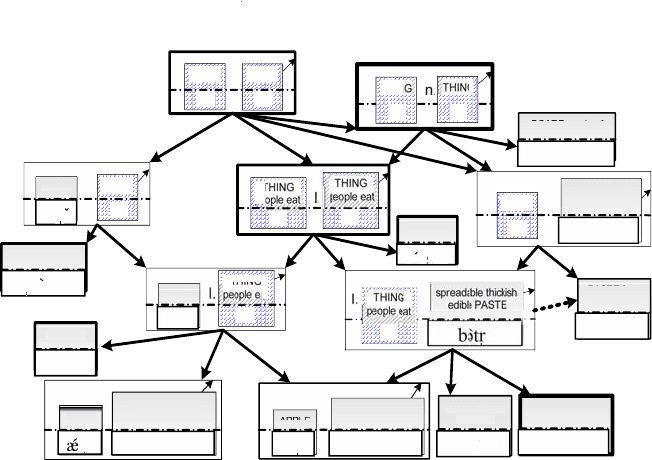

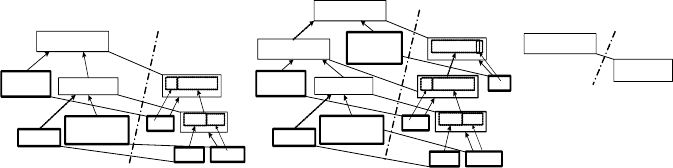

F

igure

6

Apple butter and schemas sanctioning i

t

D

K

"

D

D

KK

H

U

H

H

V

W

"

D

º

V

T

B

R

G

"

¥

R

T

B

D

Q

º

T

F

MQ"MQ

D

Q

º

V

T

3

R

RR

N

½

N

N

3

R

B

N

½

3

º

R

B

N

R

C

"

L

R

RR

N

3"

R

RR

N

F

<

F

G

º

NK

D

º

V

T

B

I

C

"

T

NKM

D

MM

º

V

T

V

V

B

R

K"P

R

V

D

º

V

T

B

3ºR

BN

RC"

L

3"

R

B

RR

NQ

º

T

V

5

V

T

5

5

B

F

250

DA

V

ID T

UGG

Y

s

emantic pole is elaborated by the construction as a whole

.

1

4

If th

esu

ffix -

z

,

in 4.u

and its subcases, were represented in a box

d

iff

e

r

e

nt fr

o

m that

o

f th

eco

n

s

tr

uc

ti

o

n a

s

a whole

(

a notational variant which is shown for 4.u in 7.u

)

, it also would be shown

as head

,

since apples

,

and all plural nouns, designate a group of items of the same

type rather than an

A

PPL

E

or other non-plural THIN

G

.

T

h

e

fa

c

t that

a

pple butte

r

has several layers of schemas above it is by no means a

r

feature unique to compounds: Fi

g

7 show

s

several la

y

ers of schemas above -

z

as

z

well. 7.ah embodies the topmost schema of 5.

y

, and is stron

g

l

y

protot

y

pical relative

to the other

p

atterns of

p

lural formation

(

the suffix

-en

, stem-vowel chan

g

e, and

z

ero

).

1

5

There may be a schema 7.ai which subsumes them all, but it is not

n

ecessary. If there is all it can say is essentially, ‘do something or nothing to mark

plurality.’ It is marked with dashed

l

in

es

an

d

r

ou

n

ded co

rn

e

r

s

t

o

in

d

i

c

at

e

it

s

m

arginal status.

14

The term often used in CG writings is the

profile determinant

(

t

profile

(

(

= ‘designatum’). Profile

determinance may be thought of as a major component

of what might be termed “semantic weight,”

t

and the notion of semantic weight approximates that of some other traditional usages of ‘head’. -z

is

z

c

learl

y

profile determinant in apples

,

as noted above

,

but apple carries the vast ma

j

orit

y

of the

semantic weight apart from specifying the kind of

profile, and this explains why analysts have

f

d

iff

e

r

ed

a

s

t

ow

hi

c

h

e

l

e

m

e

nt i

s

th

e

‘h

e

a

d

’

o

f

suc

h

wo

r

ds.

1

5

Zero morphemes and process morphemes such as the

s

tem-vowel change fit naturally in the CG model

as limiting cases of affixation. A zero morpheme analysis turns out to be identical, under CG, to an

anal

y

sis of semantic extension (Lan

g

acker 1987: 470-474).

r

ath

e

r than a kin

do

f PAPER, and so forth. This is (at least the major part of) what

c

onstitutes headship for CG: the head of a construction is that element whose

u

.

z

...

...

.

…

[+vd]

s

T

hin

g

...

...

.

…[-vd]

(ԥ)S

...

...

.

…

5

.

y

ԥz

...

...

.

…

[+st rd]

(r)

kˆ

...

.

...

.

…

áhpk ˆ

tɂȩʞiaokˆ

bréðokˆ

…

V

2

…

...

.

.

..

..

…

V

1

…

PL

man PL

man-PL

man-PL

man PL

men

PL

woman PL

woman-PL

woman-PL

woman PL

wȩʞjkˆ

ø

bou

n

ded

Thin

g

m

m

m

.

...

...

.

…

fi h PL

fish PL

fish

-

PL

fish PL

fish PL

f

dPL

deer PL

deer

-

PL

deer PL

deer PL

dir

?

…

ai.

ah.

fitPL

fruit PL

fruit

-

PL

fruit PL

fruit PL

frut

cf

.

1.

d

F

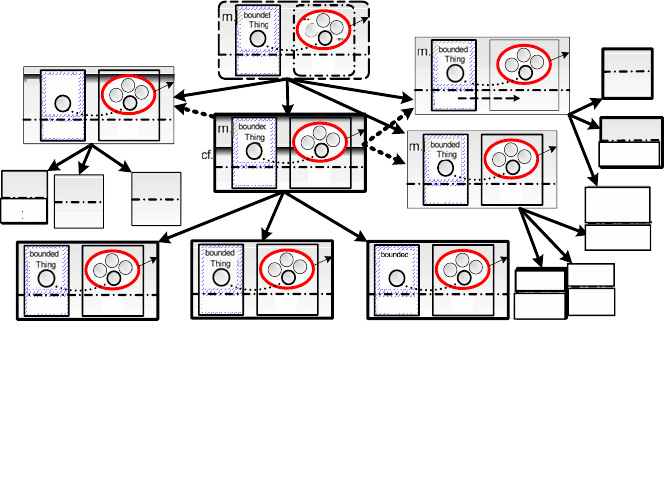

igure 7 P

lu

r

al const

r

uctional schemas

V

5

V

KN

F

T

P

B

c

hil

d

-PL

C

"MUP

C

B

o

x-PL

D

T

G"

&

T

P

B

spiritual

b

r

o

th

e

r-PL

Y

"KOP

B

H

K

H

H

5

K

C

OGNITIVE APPROACH TO WORD

-

F

ORMATION

251

3.5 Structural descriptions, creativit

y

and productive usa

g

e

Th

e

-

z

suffix, including the Stem

z

-z

c

onstruction which automaticall

y

comes

along with it (7.u), characterizes many independently-established words such as

a

pp

les

,

oranges

,

r

as

p

berries

,

tables

,

and so forth. It sanctions all these words

(section 2.5), and gives speaker-hearers a solid basis for understanding or analyzing

t

hem. The higher-order schemas 7.ah and 7.ai provide a somewhat lesser degree of

sanction (lesser because they are more distan

t

, point (c) of section 2.5). Similarly the

set of schemas 6.aa-6.ag sanction

apple-butter

and its relatives. The set of such

r

sc

h

e

ma

sw

hi

c

h

s

an

c

ti

o

n a f

o

rm

co

n

s

tit

u

t

es

it

s

s

tructural description (Lan

g

acke

r

1987: 428-433). The

y

embod

y

the lin

g

uistic

g

eneralities to which it conforms.

The same patterns, however, can also be used to craft, or to understand, new

wo

r

ds.

Su

pp

ose a

p

erson has never encountered the word guillotines before

,

but hears

someone else say it. The word guillotin

e

(4.w), we are supposing, is already

established. It is very easy to plug this autonomous, already-existent bipola

r

s

tr

uc

t

u

r

e

int

o

-z’s e-site and allow the resultant structure to sanction the particula

r

pronunciation and contextual meaning of the novel word. Essentially the same thing

would happen for a person who thinks o

f

a group of several guillotines and co-

f

activates the stem and the suffixal construction to

g

uide his pronunciation of the new

word. This kind of usa

g

e is dia

g

rammed in 4.v. As in 7.ai, the dashed lines and

r

ounded corners of the boxes indicate that the structures

,

in this case the

co

m

b

inati

o

n

so

f

GU

ILL

O

TINE

w

it

h

PL

U

RAL and of

[

I+

"

l

ti

º

ti

ti

n

]

with

[…

z

]

, as well as the

w

h

o

l

es

tr

uc

t

u

r

e

g

uillotines

,

are not (

y

et) established as part of the lin

g

uistic s

y

stem.

Similarl

y

, the N-N compound schemas of Fi

g

ure 6 can be used to sanction the

formation and understandin

g

of novel structures. Suppose an En

g

lish speaker has

n

ever heard of ‘a

pp

le

p

ancakes’ and runs across the term in a cookbook. He or she

will immediately recognize a

pp

l

e

an

d

p

ancakes

,

and perceive the extremely close

s

imilarity of this to the schema 8.aa (= 6.aa), and the likelihood in any case that,

s

ince it consists of two food nouns following each other

,

it is a subcase of the well-

e

ntr

e

n

c

h

ed

F

ood

N-F

ood

N

co

n

s

tr

uc

ti

o

n 8

.

a

d

(

=6.ad

)

. The result will be a structure

s

uch as 6.a

j

, Similarly, if one wants to construct a new form to describe a curry dish

i

n which octopus is a ma

j

or in

g

redient, the easiest thin

g

to do is to use the words

o

ctopus an

d

curry

in a construction (8.ak) sanctioned b

y

8.ad. Even in the absence of

m

ore s

p

ecific constructions octo

p

us

-

F

ood

N

o

r F

ood

N-curr

y

,

(which, if they exist,

are likely to be quite marginal), such sanction is enough.

This is how rule-governed linguistic creativity works under CG. The same

s

chematic structures that are extracted from well-entrenched (sub)cases may (though

t

hey need not) also be used as patterns for generating novel su

b

c

a

ses.

Th

us s

an

c

ti

o

n

i

s central to both the understanding of already-established forms and the production

o

f new ones. So the model is not

g

eared onl

y

towards the formation of new words

nor onl

y

towards the anal

y

sis of the existin

g

word-stock; rather it accommodates

bo

th

w

ith th

es

am

e

m

ec

hani

s

m

.

The difference between rule-governed creativity and linguistic creativity in a

m

ore general sense is a matter of the strength and closeness of the sanction the

e

stablished system affords a novel usage. This is certainly stronger for

g

uillotines

252

D

A

V

ID T

UGG

Y

(

4.v

)

, for instance, than fo

r

octopus curr

y

(8.ak), and other, less directly sanctioned,

m

ore highly creative, formations are certainly possible (e.g. Freddag

e

,

mentioned in

s

ection 1.1

,

or the Jabberwockian word slith

y

.

) They are sanctioned by extension

(partial schematicity) rather than full schematicity. But the differences are, as usual,

m

atters of degree.

To the extent that such usage to sanction the formation or understanding of non-

es

ta

b

li

s

h

ed s

tr

uc

t

u

r

es

it

se

lf

beco

m

es e

ntrenched and habitual, a structure ma

y

be

s

aid to be productive (Ta

y

lor 2002: 289-293). -

z

(or the Stem

z

-

z

construction) is quite

z

productive, as such thin

g

s

g

o. It is readil

y

, and reasonabl

y

often, called into service

t

o deal with novel usages.

App

l

e

-

FoodN is much less

p

roductive: s

p

eakers do not

c

ommonly invent new compounds of that type, though if occasi

o

n warrants, they

will no doubt do so readily enough. The

Food

N-F

ood

N

co

n

s

tr

uc

ti

o

n i

s doub

tl

ess

m

ore productive, though in many cases it will be sanctioning the novel structure

through one or more more-specific schemas on the order of 8-6.aa and 6.ab. Only

o

ccasionally will it sanction directly as in the (putative) case of 8.ak. It is certainly

n

ot as productive as the Ste

m

-

z

construction.

z

I

f CG is ri

g

ht, other lin

g

uistic models

h

ave badl

y

overestimated how much of

usa

g

e is in fact productive. For instance, words like apples

,

oranges

,

r

aspberries

,

shoes

, and so forth, are commonly thought of as produced by a grammatical rule of

pluralization operating on thei

r

respective singular forms. Thi

s

i

sv

al

ued bec

a

use

it

allows one to simplify the posited grammar by no longer listing the plural forms

t

hemselves in the lexicon. CG, to the contrary, encourages us to take seriously the

l

ikelihood that these and thousands of other commonly used plural nouns are in fact

l

earned b

y

speakers and thus do reside in

t

he lexicon as conventional units, readil

y

a

v

aila

b

l

e

f

o

r

use w

ith

ou

t

co

n

s

tr

uc

ti

ve e

ff

o

rt

.

16

E

ve

n a

wo

r

d

lik

e

g

uillotines

,

once it

h

a

sbee

n

used

a f

ew

tim

es

a

s

in thi

s

a

n

d the precedin

g

para

g

raph, is on its wa

y

to

being entrenched and conventionalized. Only a minority of the forms whose

s

tr

uc

t

u

r

e

i

s

in a

cco

r

dance with the

S

te

m

-

z

schema are likely to be fully novel. But in

z

the end, it does not matter a great deal whether a usage is novel for one or another

i

nt

e

rl

ocu

t

o

r

o

r

bo

th

.

If it i

s

n

ove

l it

c

an

be

readily constructed or understood, and if

i

t is already established, all the more so.

1

6

Bybee (2001: 109-113) summarizes a number of studie

s

that make the general point that complex

forms, regular as well as irregular, tend to beh

a

v

e as lexically stored items according to how

frequently they are used. Perhaps most relevant

t

o the immediate point is Sereno and Jongman (1997),

i

n which relatively high-frequency regularly inflected English plurals produced faster response times

than the corresponding singulars, whereas when

t

he singular was the higher-frequency item, it

produced the faster response times.

Traditional generative theory gives the impression,

i

f it does not claim as a basic fact

,

that if a for

m

follows a general pattern it is unlikely to be learn

e

d, perhaps even impossible to learn. CG suggests

r

ather that such conformity to the known tends to

m

ake the form easier and thus more likely to be

le

arn

ed.

C

OGNITIVE APPROACH TO WOR

D

-

FORMATION

253

Even the most productive morphological schemas, then, are likely to have more

es

ta

b

li

s

h

ed

than n

ove

l

subc

a

ses.

An

d

th

e

t

oken-frequency of their novel usages is

(naturally) much smaller even than the type-frequency. On the other hand, many

schemas that lin

g

uists have branded a

s

non-productive still occasionall

y

sanction

novel forms. The ‘stron

g

’ En

g

lish verb patterns (

slide

>

slid

,

break

>

k

k

b

r

oke

>

b

r

oken

,

sing

>

g

g

sang

>

sung

,

etc.) are commonl

y

cited as non-productive, but I have collected

seve

ral

do

z

e

n f

o

rm

s

that

we

r

e

n

ove

l t

o

m

e

and quite possibly to those who spoke o

r

wrote them (e.g.

I

just about froke out when she said tha

t

,

Ib

r

othe a lot easie

r

once

the window was opened

,

h

ad you ever hung-glid before

?

,

he had lotten go of the

kitestrin

g

,

with his composition [Mahle

r

] only rept mockery and derision

r

)

. It is

g

ratuitous to write off forms like these, idiosyncratic and even anomalous though

t

hey are, as performance errors or something of the sort, not to be accounted for by

t

he same

g

rammatical mechanisms that explain novel usa

g

es elsewhere.

A

structure’s productivit

y

is somewhat independent of its prominence or de

g

ree

o

f establishment, thou

g

h of course it results in increased usa

g

e and so naturall

y

i

ncreases them. For example, there is a family of nou

n

-age words

,

where -ag

e

u

sually means a mass-type construal of (many instances of) the noun. This is a rathe

r

c

ommon pattern, and a very old one. Some e

x

amples are relative

l

y transparent (e.g.

acreag

e

,

b

aggag

e

,

footag

e

,

paren

t

ag

e

,

l

eafage

,

usag

e

), though even in these cases

t

heir meanings are typically a good bit less than fully predictable (i.e. they are not

full

y

compositional semanticall

y

). E.

g

. a collection of paper ba

g

s does not constitute

b

a

gg

a

ge

,

nor a collection of parents parenta

g

e

,

nor a collection of feet

f

oota

ge

¸

a

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

æmiˆ

ma

j

or in

g

redient fo

r

l.i.

lPIE

apple PIE

apple PIE

apple PIE

apple PIE

pp

ʝmiˆpáj

PANCAKES

PANCAKES

PANCAKES

PANCAKES

CS

pǚnke

j

ks

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

ǚmiˆ

ma

j

or in

g

redi ent for

l

.

l.

ac.

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

æmiˆ

associa

t

ed

w

i

t

h

n.

i.

s

i

g

ni

f

icant in

g

redient o

f

ad.

n.n.

assoc

i

a

t

ed

wit

h

ag.

aa.

THING

p

people eat

…

…

people eat

…

THING

…

THING

…

THING

…

s

i

g

ni

f

icant in

g

redi ent

/

component o

f

af.

n

.

THING

… …

aj.

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

APPLE

ǚmiˆ

i.

PANCAKES

PANCAKES

PANCAKES

PANCAKES

CS

pǚnke

j

ks

CURRY

CURRY

CURRY

CURRY

CURRY

hĴˆi

OCTOPUS

OCTOPUS

OCTOPUS

OCTOPUS

OCTOPUS

ԥs

ma

j

or in

g

redient fo

r

ak.

CURRY

CURRY

CURRY

CURRY

hĴˆi

OCTOPUS

OCTOPUS

OCTOPUS

OCTOPUS

OCTOPUS

ákt ԥpԥs

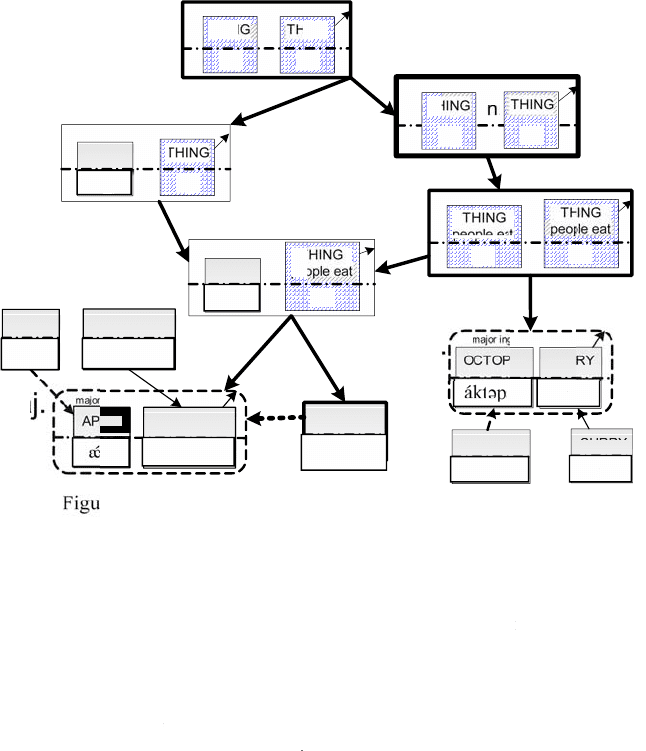

Figure 8 Productive use of compound constructional schemas

3

º

R

NB

R

C

"

L

C

p3"PMG

¥

MU

3

"

R

NB

p

3

"PMG

¥

M

U

3

"

R

N

B

3"

R

N

B

C

"M

C

V

R

U

C"MVRU

M

T

MM

"BK

T

M

T

M

M

"BK

T

3

"

R

N

B

254

DA

V

ID T

UGG

Y

p

ile of fallen leaves is no

t

leafage

t

,

though the leaves belonging to a particular tree

are, and so forth

)

. Sometimes -ag

e

a

pp

ears where it is less than obvious what noun

(

or other kind of stem

)p

recedes the -age

(

e.g

.

carnage

,

courage

,

g

arbag

e

,

pillag

e

,

s

ilag

e

,

v

illag

e

,

v

intag

e

.

)

1

7

Thi

s

n

ou

n-age pattern was rarely used during my lifetime,

as far as I am aware

,

to form novel stru

c

tures, until the mid-1990’s, when I suddenly

s

tarted hearing many new forms from my children and others of their generation.

(

E.

g.

That woman has whole closets

f

ull o

f

shoea

ge

,

o

r

We need some more chaira

g

e

in he

r

e

, or as a prett

yg

irl walked b

y

at the beach, Whoa, there

g

oes some serious

b

abea

g

e

!

) What chan

g

ed? The co

g

nitive routine of usin

g

noun-

age

t

os

an

c

ti

o

n a

n

ovel structure was repeated enough that in certain social groups it achieved unit

status. In other words

,

noun-ag

e

became

p

roductive. Its extension to a

p

ro

p

er-noun-

age

co

n

s

tr

uc

ti

o

n

suc

h a

s

Freddag

e

is still norm-bending and quite creative, but if it

spread enough it too would become normal.

Productivity, in sum, is one more of the gradual parameters of CG. It is not the

c

ase that productive morphology can be taken care of in one module and non-

productive morpholo

gy

in another: the two cate

g

ories overlap far too much, and

i

ndividual patterns var

y

far too much alon

g

the parameter of productivit

y

, for that to

be

f

e

a

s

i

b

l

e.

I

t is worth noting that -

z

is non-absolute in another important way: by no means

z

every word ending in [z] is sanctioned by it. Nouns like

ha

z

e

an

d

rose

are not

p

lural,

no

r ar

eve

r

bs

lik

e

b

r

oils

or

slumbe

r

s

,

and though words like

snee

z

es

an

d

fries in

s

ome contexts are plural nouns in -z, in other contexts they are singular verbs. This

l

ack of absoluteness is quite typical with relatively short affixes, though in some

c

ases somethin

g

nearer absoluteness holds (e.

g

. the vast ma

j

orit

y

of words endin

g

in

[

i

zm

]

are Ste

m

-

ism

constructions.) And of course most words beginning with [

æp

B

p

p

l

]

ar

e

a

pp

le

-

Stem structures (though words like A

pp

alachian m

us

t

be co

n

s

i

de

r

ed

a

s

well

)

.

3

.6 Sanction (o

f

various kinds)

f

rom components

Th

es

t

em

appl

e

(4.i) is represented as identical to a part (the first part) of apples

(

4.a), and similarl

y

g

uillotin

e

(4.w) is shown as identical to the first part of

guillotines (4.v). This is a common type of component relationship, but not the only

o

ne. It is also common for the relationship to be a one-way schematic relationship.

Th

us

in apple butte

r

the meaning of

r

apple is something like

PEELE

D

,

C

ORED

,

C

OOKED AND P

U

REED MASS APPL

E

(

S

)

. This is either an elaboration of a more

schematic meaning for apple which despecifies the count/mass distinction, or else an

extension from somethin

g

like the topmost schema of 5.x. In neither case is the

r

elationship one of identit

y

. More strikin

g

l

y

, the desi

g

natum of

butter

in

r

apple butter

i

s somethin

g

that would not in other contexts be calle

d

butter

at all. And there are

r

m

any other cases where more drastic results obtain. At the far distant end might be

something like

e

avesdro

p

where the meaning of

eaves

may be something like ‘place

17

It also occurs with verbs, forming a noun which may be a count noun (e.g. carriage

,

haulag

e

,

l

uggage

,

marriag

e

,

package), and some forms can be analyzed as having either a noun or a verb stem (e.g.

postag

e

,

w

reckage

)

. Note that

v

illag

e

,

listed in the text

,

is also a count rather than a mass noun.

C

OGNITIVE APPROACH TO WOR

D

-

FORMATION

255

where one might listen surreptitiously’, and

d

ro

p

might refer to words being spoken

where they can be overheard. In such cases the relationship between the component

as an independent structure and its usage within the complex construction is not one

o

f identit

y

or of full schematicit

y

.

Sanction at the phonolo

g

ical pole also ma

y

var

y

from identit

y

to full

schematicity to partial schematicity. [

æ

"

pl

B

]

may be fully recognized, unchanged

except perhaps in very minor details, in [

æ

"

pl

B

z

]

. Similarly

[

i

v

z

]

and [drap

]

are

q

uite

r

ecognizable in

[

i

¸

i

i

vzdra

p

aa

]

, despite the imposition of a special stress contour (much

l

ike the ones on [

æ

"

p

B

pp

l

b

º

tr

B

]

or

[

æ

º

p

B

pp

lpa

j

a

])

. But [

æ

¸

n

la

j

aa

z

]

(the phonological pole of

analyze) is not so easily recognizable within

[

næ

¸

l

s

+º

s

](

analysis

)

, nor [

k

nsi

¸

i

i

v

]

(

conceive

)

within [

ka

nse

º

pt

](

concept

).

t

C

G simpl

y

requires of a component that it sanction some part of the complex

c

onstruction. This can range from sancti

o

ning through a rather tenuous relationship

o

f partial schematicity (as in the case of EAVES as a com

p

onent o

f

E

AVESDRO

P

o

r

[

æ

¸

n

la

j

aa

z

]

as a com

p

onent o

f

[

næ

¸

l

s

+

º

s

]

) throu

g

h cases where there is a more solid

partial schematicit

y

relationship (the case of protot

y

pical

A

PPL

E

as a com

p

onent o

f

A

PPLE B

U

TTER) to cases of full schematicit

y

(the case of schematic PI

E

a

s

a

c

om

p

onent o

f

A

PPLE PI

E

or o

f[

d

rap

]

as a com

p

onent o

f

[

i

¸

i

i

vzdra

p

aa

]

) to cases of identit

y

(

the cases of

APPLE

and [

æ

"

pl

B

]

as com

p

onents o

f

a

pp

les

.)

The differences between

t

hese types of components are matters of degree, and there is no non-arbitrary

d

ividing line where they could be split into disjoint categories.

B

esides this cline of similarity of the component to what actually occurs in the

c

onstruction

,

there is a cline of analyzabilit

y

,

namely the degree to which the

c

omponents are discerned at all. In some constructions (e.g.

cock

r

oach hotel

) the

ll

c

omponents are likely to be highly salient as such. It is hard to imagine someone

sa

y

in

g

or hearin

g

the construction without discernin

g

the parts (i.e. stron

g

l

y

activatin

g

the schemas

cock

r

oach

an

d

hotel

to sanction the parts of the construction.)

l

Bu

t f

o

r

s

tr

uc

t

u

r

es

lik

e

b

reak

f

as

t

,

o

r

ci

g

arett

e

,

o

r

f

ilth

,

o

r

halte

r, it is entirel

y

normal

for speakers to activate the whole without particularly activating

b

r

eak

,

fas

t

,

cigar

,

-ette

,

vile

,

-

th

,

halt

,

o

r

-

e

r

,

and in fact many speakers will claim they never had

realized that those pieces might

be components of the words.

t

Y

et a third parameter of difference is the degree to which the components

t

ogether exhaust the meaning of the con

s

truction. (This parameter is often calle

d

compositionalit

y

.

)

Apples does not mean much, or perhaps anything, beyond what

c

ould have been deduced from the meanin

g

s of appl

e

an

do

f

-

z,

g

iven the mode of

t

heir combination, nor is there much if anything in [

æ

"

pl

B

z

]

that does not come fro

m

[

æ

"

pl

]

and [..

.

z

]

. But in many constructions there are important parts of the meaning

and (a bit less often) the sound that cannot well be attributed to an

y

of the

c

omponents. The notion of the first noun bein

g

an in

g

redient or component of the

second is

p

art of the construction in 6-8.aa., 6.ab., 6-8.ad. and 6-8.af. In the abstract,

t

here is not a good way to tell from the components a

pp

le

and

butter

that the

r

d

esignatum of apple butter is not, for insta

n

c

e, an apple that h

a

s been packed with

butter, or butter flavored with apples, or any of a number of other possible

c

onstruals. And, once more, other cases are often more extreme in this regard. Fo

r

256

DA

V

ID T

UGG

Y

i

nstance, no one could get fro

m

cock

r

oach

o

r

f

r

om

hotel

the information that what is

l

designated is in fact a plastic compar

t

m

e

nt in

s

i

de o

f

w

h

ic

h

coc

kr

o

a

c

h

es

ar

e

p

oisoned, or fro

m

cocoa

an

d

butter

that

r

cocoa butter

is an ingredient for skin

r

lo

ti

o

n

s.

N

o

r

cou

l

do

n

e

t

e

ll fr

om

shut

and

t

out

that a

t

shutout

is a game in which one

t

team is prevented from scoring, or fro

m

cow

an

d

lick

that a

k

cowlick

is place where

k

h

air grows in a swirl on a person’s head, or fro

m

slam

an

d

-er

that a

r

slammer

is a

r

j

ail, or fro

m

A

dam

’

s

an

d

appl

e

th

a

t

a

n

Adam

’

s

apple is a prominent lar

y

nx.

A

pples

,

then, is a limitin

g

case alon

g

three parameters: (i) its components

s

anction their respective pieces of the con

s

truction b

y

relationships of full identit

y

r

ather than more distant or

p

artial schema

t

icity; (ii) they are prominently discernible

i

n the construction, so the construction is highly analyzable; and (iii) the

c

onstruction is highly compositional: there is little or nothing of the meaning or

s

ound that is not sanctioned by one of the components. Such structures fit the

building-block model reasonably well, but

t

h

eo

th

e

r

c

a

ses we

ha

ve

m

e

nti

o

n

ed do

n

ot. For linguistic theories which assume the building-block model, cases like these

are problematic and must be dealt with b

y

so

m

e

m

ec

hani

s

m

o

th

e

r than th

eo

n

e

that

h

an

d

l

es

apples

.

In CG none of them causes an

y

theoretical problem;

18

rather the

y

are

all handled b

y

the sin

g

le mechanism of sanction. Sanction can var

y

in its distance

and partiality, in its importance or even whether it is invoked at all

,

and in its

c

ompleteness of coverage. The fact that a

pp

les an

do

th

e

r

s

tr

uc

t

u

r

es

lik

e

it

s

tan

d

at

o

ne extreme on these three parameters does not make them different in kind fro

m

structures which are more towards the middle or the other end

,

nor does it cause a

d

isconnect between the ways they are handled by the theory.

3

.7 Components and patterns for the whole; overlapping patterns and multiple

anal

y

ses

A

s we have seen

(

section 3.2

)

, the second com

p

onent of a

pp

les

,

-z

,

does not

c

onsist onl

y

of the part of a

pp

les that does not overla

p

with a

pp

l

e

.

Rather it includes

,

as an invariant feature or s

p

ecification, the Stem-

z

construction (4.u), which is

z

sc

h

e

mati

c

f

o

r th

ew

h

o

l

eo

f apples

.

This is in fact another kind of limiting case: a

c

omponent which sanctions the whole of the construction rather than

j

ust a prope

r

s

ubpart of it.

T

he total overlap of the semantic area sanctioned by apple by that of -

z

is

z

n

oteworthy. Under the building-block model it does not make sense that the

c

omponents should overlap at all, but under the CG model it is not only natural, it is

v

irtuall

y

inevitable (point (1) of section 4.1). It is, in fact the overlap of components

that permits their bein

g

united into a coherent whole. And it causes no problem fo

r

the one piece to totall

y

overlap another.

Of course constructional schemas like 6.aa-ag also overlap completely with the

s

pecific structures they sanction. They also can be seen as components at the

l

imiting pole of inclusiveness. And of course the cases that have part of the

18

This is not to sa

y

, of course,

t

hat the

y

are necessaril

y

all equall

y

eas

y

for speakers to learn or use.

C

OGNITIVE APPROACH TO WOR

D

-

FORMATION

25

7

semantics and phonology more fully specified (6.aa-ad, 6.ae) are especially simila

r

to

affixal

s

tr

uc

t

u

r

es

lik

e

4

.u.

A

related issue is that of multiple analyses, cases where more than one set of

c

omponents (includin

g

constructional sch

e

m

as

)

can sanction a structure. CG

provides no bar to this. A word like

h

an

g

man ma

y

be sanctioned in some speakers’

m

inds b

y

h

an

g

,

man

,

and a Verb+Sub

j

ect compound schema (so that a han

g

man is

u

n

de

r

s

t

ood

t

obe

a

man

w

h

o

hangs people, just as cutgrass i

s

grass that

w

ill

cut

you), while for other speakers it may be sanctioned rather by a Verb+Object

c

ompound schema (so that a hangman is a person who hangs

a

man

,

just as a killjo

y

i

s person who

kills

people’s jo

y

.

) For yet other people both schemas may be

c

oncurrently active.

F

or any of the above simultaneous sanction from an unanalyzed, unitary,

m

orpheme-like ste

m

han

g

man

or

cut

g

rass

or

kill

j

o

y

is perfectl

y

possible. This is of

c

ourse closel

y

related to the issue of anal

y

zabilit

y

(section 3.6); as sanction b

y

such

an unanal

y

zed structure is becomes primar

y

over sanction from other possible

c

omponents, the analyzability of the form fades.

3

.8 Constituency

A

n

o

th

e

r r

e

lat

ed

i

ssue

i

s

that

o

f

d

iff

e

r

e

nt

co

n

s

tit

ue

n

c

i

es o

r

o

r

de

r

so

f

co

n

s

tr

uc

ti

o

n

and analysis. When more than two components are combined, there often is a

standard order of combinin

g

or of decomposin

g

a whole into its parts. This

c

orresponds to what is

g

enerall

y

called

constituent st

r

uctu

r

e

.

CG views constituent

structure as by nature somewhat variable, and typically no great issue hangs on the

o

rder in which things are combined, or analyzed out. This is particularly true of

p

hrase or clause-level structures, but even within words it often holds true.

Langacker lays this out clearly (1987: 310-324, 2000: 147-170), saying “the kinds of

c

onstituents reflected in syntactic phrase t

r

ees

ar

e

n

e

ith

e

r

esse

ntial n

o

r f

u

n

d

am

e

ntal

t

o linguistic structure. They are instead …

emergent

in nature, … arising in language

t

processin

gj

ust in special (thou

g

h not unt

y

pical) circumstances.”

Th

ewo

r

d

unbelievabl

y

mi

g

ht be anal

y

zed first into

un

- an

d

b

elievabl

y

,

and

b

elievabl

y

int

o

believe

an

d

-

abl

y

,y

ieldin

g

the constituenc

y

un

[[

believe

]

abl

y

](

9.al

)

,

o

r it might be first

unbelievable

an

d

-l

y

,

then

un

- an

d

believable

,

then

believe

an

d

-

able

,

in which case

[

un

[[

believe

]

able

]

ly

(9.am) emerges, and there are a number of

o

ther

p

ossibilities as well.

Believable

,

b

elievabl

y

,

unbelief

,

f

f

unbelievable

,

-abl

y

,

and

(

arguably, perhaps (un)deniably) un-…-able an

d

u

n-…-abl

y

,

are all pre-established

units in many speakers’ inventories, and can be pulled “off the shelf” to form the

b

a

s

i

s

f

or

u

nbelievabl

y

or to sanction parts of it or

each other. And of course

r

unbelievabl

y

is itself a unit which can be activated alone

(

9.an

)

.

19

The meanin

g

s and

t

he phonolo

g

ical structures add up to be the same thin

g

in an

y

case, under CG, and

19

Sa

y

in

g

that these constituencies are all possible does not mean the

y

are

a

l

l equall

y

probable. The

i

ndependent existence or not, and degree of entrenchment, of such word partials as unbelief

,

f

f

believable

,

-ably

,

un-…-able, etc., clearly has an effect on the lik

e

lihood that they will be prominently

r

eco

g

nized in the word or used in its constructi

o

n

.

Al

so

th

e

nat

u

r

eo

f th

eco

n

s

tr

uc

ti

o

nal

sc

h

e

ma

s

available to guide the construction or analysis affects things.

2

58

DA

V

ID T

UGG

Y

different speakers may well do it differe

n

tly, or do it differently on different

o

ccasions, and still communicate perfectly well. What matters more is

how

th

e

pieces are combined (or analyzed out), not

when

or

in what order

or even precisely

r

w

hich pieces

g

et combined (or analyzed).

4

.

OV

ER

V

IE

WO

F

O

THER I

SSU

E

S

Man

y

theories start out presupposin

g

the validit

y

of the buildin

g

-block and

c

ontainer metaphors, assuming that lexicon, morphology and syntax are

i

ncommensurate ‘modules’ operatin

g

b

y

quite different rules, that the stem / affix,

c

om

p

onent / noncom

p

onent, and com

p

onent

/

(morpho)s

y

ntactic pattern differences

are absolute, that either a form is 100% in the lexicon or 100% produced by the

g

rammar, that either a pattern is productive or it is not, and so forth. They typically

g

o on to posit man

y

other absolute cate

g

ories, exceptionless principles, and strict

r

ules. Many of these will show up under C

G

as strong tendencies, for which it is

always of interest to seek some sort of functional explanation, but they will not be

a

bso

l

u

t

e.

2

0

The following sections give extremely brief characterizations about how certain

i

ssues are dealt with under

CG

.

4.1

V

alence

Valence involves the relationships between the components of a structure. Ver

y

briefly:

1. There always is some overlap of meaning (correspondence of parts of the

m

eanings) which forms the connection between two components. Even if you try

to invent a form composed of semanticall

y

unconnected parts, people will

c

onnect them. Often these connections are multiple, not infrequently they

i

nvolve quite peripheral parts of the meaning.

2

0

Much linguistic argumentation has proceeded by

assuming a hard-and-fast distinction between

y

c

ategories, and then exhibiting as representative only cases from opposite ends of the spectrum, which

i

n

deed

l

oo

k rath

e

r

d

iff

e

r

e

nt

.

In-

be

t

wee

n

c

a

ses

a

r

e

either (1) crammed uncomfortably into these

absolute categories, (2) consigned to a sep

a

r

ate compartment or module‘, or (3) ignored.

U

NBELIEVABLY

ҠҠҠ…ԥblì

bԥlív

bԥlívԥblì

ԥn…

ԥnbԥlívԥblì

BELIEVABLY

not

R

ELATIO

N

BELIEV

E

SO

IT

C

AN BE

(

process

)

ED

UNBELIEVABL

E

ҠҠҠ…ԥbԥl

bԥlív

bԥlívԥbԥl

ԥn…

ԥnbԥlívԥbԥl

BELIEVABLE

no

t

R

ELATI

ON

BELIEVE

ABLE t

obe

(

process)ed

ԥnbԥlívԥblì

ҠҠҠ…li

UNBELIEVABLY

SO

A

S

T

O

be (relation

)

a

.

b.

c.

ԥnbԥlívԥblì

UNBELIEVABLY

F

igure 9

Alte

r

nate constituencies