Sioshansi F.P. Smart Grid: Integrating Renewable, Distributed & Efficient Energy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

enhanced by the new technologies of the smart grid, but there

is a huge amount of work to be done to realize the potential.

For those of us working at the CAISO these are exciting

times. The authors of this chapter span the whole range of

CAISO core functions, from smart grid strategy and

implementation (Sanders), to grid operation and spot market

performance (Rothleder), to market redesign and

infrastructure planning policies (Kristov). We see state

environmental policy as the main driver of the transformation

of the supply fleet, while smart grid and other new

technologies such as energy storage provide the means to

achieve the environmental goals. At the CAISO this means

undertaking several parallel initiatives to facilitate and

prepare for the new world, while maintaining through

cross-functional collaboration a view of the big picture that

reveals how all the changes interact and all the pieces fit

together.

Acronyms

AGC Automatic Generator Control

CMRI (ISO

Application)

CAISO Market Results Interface

DNP Distributed Network Protocol

DR Demand Response

DRS Demand Response System

DSA Decision Support Applications

EMMS Enterprise Model Management System

EMS Energy Management System

EPDC Enterprise Phasor Data Concentrator

GIS Geographic Information System

HTTPS Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure

IEC 61850 International Electrotechnical Commission

LMP Locational Marginal Pricing

NAESB North American Energy Standards Board

371

NASPI North American SynchroPhasor Initiative

OASIS

Organization for the Advancement of Structured

Information Society

OASIS (ISO

Application)

(California ISO) Open Access Same-Time Information

System

OpenADR Open Automated Demand Response

PDC (Synchro) Phasor Data Concentrators

PEV Plug-In Electric Vehicles

PMU (Synchro) Phasor Measurement Unit

PV Photovoltaic

RIG Remote Intelligent Gateway

RTDMS Real-Time Dynamics Monitoring System

SCADA Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition

SIBR (CAISO

Application)

Scheduling Infrastructure Business Rules

SOAP Simple Object Access Protocol

VSA Voltage Stability Analysis

WECC Western Electricity Coordinating Council

WISP Western Interconnection Synchrophasor Project

372

373

Chapter 7. Realizing the Potential of

Renewable and Distributed Generation

William Lilley, Jennifer Hayward and Luke Reedman

Chapter Outline

Introduction 161

Modeling Approach 165

Modeling Framework 165

Scenario Definition 169

Results and Discussion 172

Modeling Results 172

Value of Potential Benefits 180

Conclusions 181

References 182

Smart grids provide a mechanism to help unlock the economic, social, and environmental benefits that

might be realized through more efficient use of large centralized renewable generation and the

deployment of renewable and non-renewable resources located near the point of use Economic

analysis suggests that the savings from allowing greater use of intermittent resources are large and may

well cover much of the costs in developing smart grid technologies These benefits are additional to a

number of other potential benefits already identified for smart grids, including increased system

security, enhanced consumer interaction, and improved power quality

Renewable energy resources, climate change, scenarios

Introduction

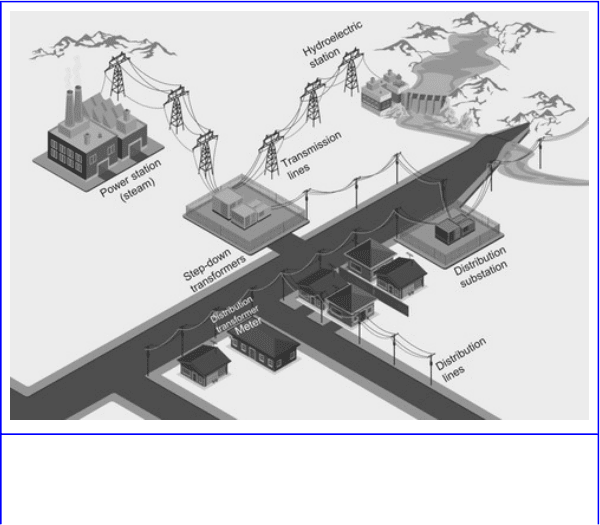

In a traditional network such as the one shown in Figure 7.1,

electricity is produced by large centralized plant located

remote to the user. These plant typically convert energy

contained in a fuel (e.g., coal, gas, or nuclear material) into

374

electricity via some form of spinning machine, typically a

turbine. The output from these prime movers is fed to a

generator, which develops electricity at low voltage. This

electricity is then converted to a high voltage for efficient

transport through the use of a step-up transformer. The

electricity travels through the transmission network toward

the end-user at high voltage to reduce losses. When the

electricity nears major load centers (e.g., a town), it enters the

more widely spread distribution network for transport to

numerous end-users. When entering the distribution network

the voltage is brought to a lower voltage level by a step-down

transformer. This step might typically occur a number of

times before reaching the final consumer.

Figure 7.1

A simplified view of electricity generation and transfer.

375

Source: CSIRO

Typically the amount of power produced by a given plant is

determined by a central control authority or market operator.

In Australia's eastern states, for example, this is the Australian

Energy Market Operator (AEMO). In the United States,

market operators are called independent system operators

(ISOs) or regional transmission organizations (RTOs).

1

These organizations control the dispatch of power to meet

system-wide demand. Dispatch takes into account issues such

as scheduled outages, power flows including losses, the price

offered by each generator for supplying electricity, and a

prediction of aggregated demand. The system is then

balanced through small changes to dispatch and ancillary

services, which control frequency and voltage.

1

Chapter 6 describes CAISO, and Chapter 17 describes PJM.

Because these large centralized plant are being fed a

consistent source of fuel, their output is readily controlled and

predictable. In response to concerns about climate change as

well as fuel diversity, energy security, and a host of other

reasons, there is a movement toward bringing large renewable

generators into the supply system. These systems are typically

connected where there is a good natural resource and where

there is access to the high voltage transmission system or

higher voltage sections of the distribution network. A number

of these renewable generators operate by capturing a source

of energy, which is variable by nature, for instance the wind

or sun. As a consequence their output is less controllable and

less predictable; hence these plants are referred to as

intermittent renewable generators. Because their output can

vary, their use can be problematic for the finely tuned

376

electricity system, which must balance supply and demand

within quite stringent limits.

The rise in electricity prices in many developed countries has

been driven by expenditure on distribution networks to meet

growing demand from large consumer devices such as air

conditioners. The use of this equipment can lead to large

demands on supply at certain times of the year, in this case on

very hot days. The network must be rated to meet this large

demand that typically occurs on only a small number of days

per year. In response to rising prices to deal with this demand,

there has been a trend toward the introduction of measures to

better understand and control demand and to provide local

supply to avoid transmission and distribution losses. This

local generation is referred to as distributed generation (DG),

also often referred to as embedded generation.

The introduction of DG into a distribution network poses

potential problems to a system essentially designed to cater to

one-way flow from large centralized plant located in remote

locations to the end-user far away. These new two-way flows

need to be measurable and controllable to ensure that issues

around safety and performance are not unduly affected by the

use of DG.

Adapting the way in which energy is used and supplied is a

major challenge facing the world's economies as they attempt

to reduce emissions in response to climate change and to

reduce large expenditures in the supply and transfer of

energy. Ensuring that new sources of energy supply and

management can be integrated with existing technical and

economic frameworks is a challenge being addressed through

the emergence of smart grid infrastructure and control

techniques, including intermediary steps such as minigrid

377

architecture, further described in Chapter 8. In this chapter the

results of a modeling analysis are provided that considers the

value that smart grids may provide by enabling the increased

use of intermittent renewable and distributed generation.

As smart grids represent a new and evolving way in which

energy is generated and delivered, the cost and benefits are

yet to be well characterized. Programs such as Smart Grid,

Smart City in New South Wales, Australia

(http://www.ret.gov.au/energy/energy_programs/smartgrid/

Pages/default.aspx), and SmartGridCity in Boulder, Colorado

(http://smartgridcity.xcelenergy.com/), have been developed

to explore these issues and report outcomes to industry and

the wider community. In other studies such as a recent report

by EPRI [1], efforts have been made to quantify at a high

level the potential cost and benefits associated with smart

grids.

In the case of EPRI's report, the major benefits considered

are:

• Allowing direct participation by consumers;

• Accommodating all generation and storage options;

• Enabling new products, services, and markets;

• Providing power quality for the digital economy;

• Optimizing asset utilization and operation efficiently;

• Anticipation and response to system disturbances;

• Resilience to attack and natural disaster.

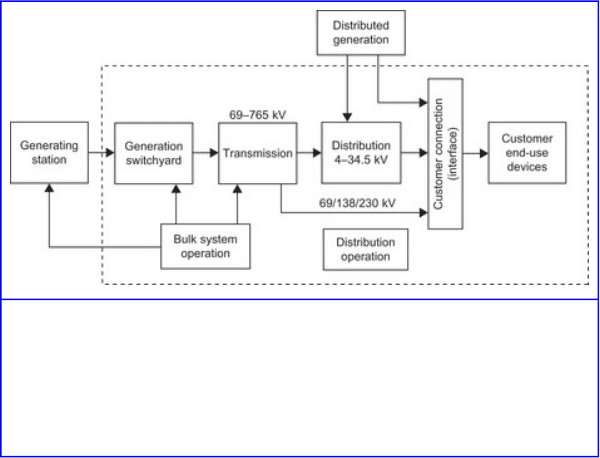

However, as can be seen in Figure 7.2, the benefits associated

with changes to the development and use of centralized and

distributed generation were outside the scope of their study.

378

Figure 7.2

Modeling scope for EPRI cost/benefit analysis of smart grid in the United

States; the dashed line represents the components of the energy sector in the

scope of the EPRI study [1].

Source: EPRI [1]

Potential changes that may be required by the smart grid to

deal with intermittency include:

• Better forecasting techniques for grid-connected wind and

solar generation (e.g., the Australian Wind Energy Forecast

System [AWEFS] in Australia and AEMO [2]) to allow

more accurate dispatch of supply to match demand;

• Better control of the output of intermittent renewable

generators to constrain plant ramp rates, that is, the rate in

which output varies (e.g., the semi-scheduled rules within

the Australian National Energy Market; AEMO [3]);

• The use of storage including electric vehicles (see

Chapter 5, Chapter 18 and Chapter 19) to increase revenue

earned by renewable generators;

• The adoption of new architectures such as mini grids (see

Chapter 8) that can provide local areas with high

379

penetration of intermittent generation through a

combination of sophisticated control of generation devices

and demand.

This chapter attempts to put a value on the benefits of a smart

grid on a global scale. The analysis posits that greater

amounts of renewable and distributed generation can be

facilitated by a smart grid. Previous studies such as EPRI [1]

do not estimate the benefits of a smart grid on the integration

of renewable and distributed generation. This chapter presents

modeling of the global electricity sector to examine the

impact of intermittency constraints on renewable generation.

Varying this constraint in the model is a means to estimate the

potential benefits of a smart grid in facilitating greater

deployment of renewable generation.

Section “Modeling Approach” presents the methodology of

the economic modeling. Section “Results and Discussion”

presents results and discussion of the modeling. Finally,

section “Conclusions” provides conclusions resulting from

the analysis.

Modeling Approach

The modeling in this chapter complements the approach used

by EPRI [1] in their U.S. study by examining—using simple

assumptions—the economic benefits derived from increasing

levels of intermittent distributed and renewable generation in

the grid over a long time frame. In the context of increasing

global electricity demand, there are numerous supply-side

options that may become economically feasible over time.

The model assumes that smart grids will allow increasing

levels of intermittent renewable and distributed generation

into electricity networks. Prior to discussion of the scenarios,

380