Sioshansi F.P. Smart Grid: Integrating Renewable, Distributed & Efficient Energy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

neighborliness, a strong sense of place,

and a relatively slow pace of life [9, p.

616].

While AC is evidently only one influence among many, and

some of these changes are clearly positive, Arsenault

convincingly argues that AC was a significant agent of such

changes. For example, the demise of a vernacular

architecture—open porches, high ceilings, breezeways, and so

on—that AC helped bring about not only facilitated the

replacement of front porch conversations by a retreat behind

closed doors and windows, but “also influenced the character

of southern family life” [9, p. 624] in more subtle and

fundamental ways. In tandem with other, sometimes linked,

developments, such as air-conditioned shopping malls and

TV, Arsenault concludes that “even if, on balance, residential

air conditioning strengthened the nuclear family, the impact

on wider kinship networks probably went in the opposite

direction” [9, p. 625]. That AC affected fundamental aspects

of southern culture more generally is underlined by how it

“modulated the daily and seasonal rhythms that were once an

inescapable part of southern living…assault[ing]…the South's

strong ‘sense of place’” [9, pp. 627–8].

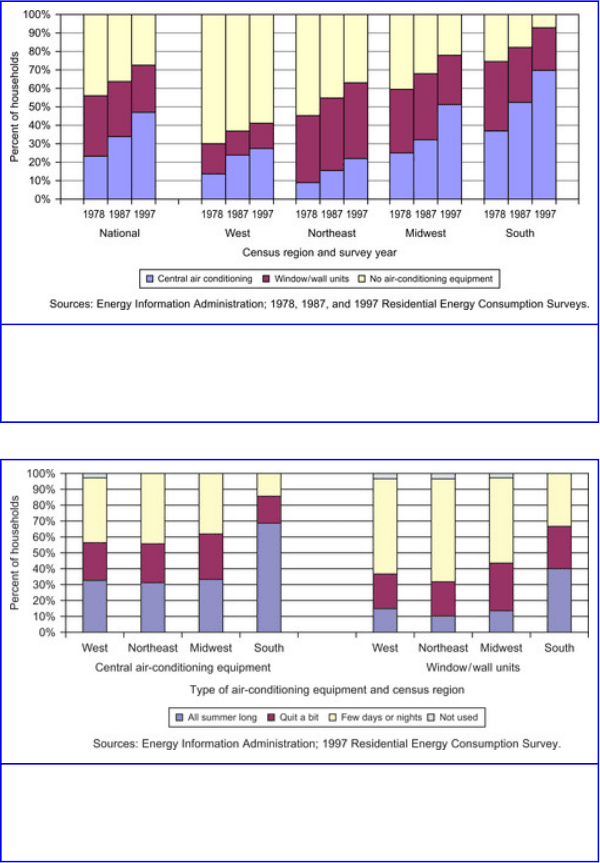

Figure 2.2 shows how recent statistics bear out this trajectory.

From 1978 to 1997 centrally air-conditioned households

increased from 23% to 47% across the United States as a

whole while in the South 93% of households were

air-conditioned by 1997 [10]. Figure 2.3 highlights how this

broader influence of AC was not simply a function of its

availability but also of the degree of use, with AC use in the

South more than double that in the rest of the country.

171

Figure 2.2

Type of air-conditioning equipment by census region, 1978, 1987, and 1997.

Figure 2.3

Frequency of air-conditioning usage by census region, 1997.

Table 2.1 shows how, across the three main residential

categories of U.S. electricity end use (AC, space heating, and

172

water heating) AC demonstrated a small but notable increase

in share from 1987 to 2009, up from 15.8% to 17.9%, while

the share of both space heating and water heating declined

from 10.3% to 9.1% and from 11.4% to 9.1%, respectively

[11].

Table 2.1

Percent of U.S. Electricity Consumption by End Use

End Use 1987 1990 1993 1997 2001 2009

AC 15.8 15.9 13.9 11.8 16.0 17.9

Space Heating 10.3 10.0 12.4 11.4 10.1 9.1

Water Heating 11.4 11.2 10.3 11.0 9.1 9.3

Total Appliances 62.5 63.0 63.4 65.9 64.7 63.7

Source: EIA –http://www.eia.gov/emeu/recs/recs2001/enduse2001/

enduse2001.html; http://www.eia.doe.gov/tools/faqs/faq.cfm?id=96&t=3.

Similar patterns are now evident across the globe. In the

authors’ home state of New South Wales, for example, 50%

of households were air conditioned by October 2006 [12],

while the rapid growth of AC in Western Sydney, particularly

the use of split mini-systems, is putting a considerable strain

on local electricity substations [13, p. 5].

In a highly stylized article Prins [14] indicted Americans as

“condis” addicted to “coolth.” “Condis”

abhor the heat and the wet. They inhabit

civilization: Their natural habitat is the

civis…They fear and detest the things that

live in the Wild Woods. They insulate

themselves from the Wild. In summer,

they take Coolth with them to do this, to

tame it. They seek predictability. They

hate the spontaneous. Their lives

173

celebrate the linear and overthrow of the

cyclical. Day is as Night and Night is as

Day to them. Time is Digital [14, p. 252].

While Prins's article has been subject to considerable

criticism

5

it's notable that others reinforce the charge that

AC-related practices and behaviors meet standard definitions

of addiction [15, pp. 183–85]. Prins ultimately argues that

“fracturing the right to Coolth…[requires] the need to

reconstruct America's contemporary cultural norms” [14, p.

258]. Interestingly many of Prins's critics charge that he

overlooks key structural issues, such as how AC emerged in

parallel with networked electricity supply. This underscores

how “condis” addicted to “coolth” are not only the result of

the psychological makeup of consumers but also the systemic

imperatives embedded in networked electricity supply

systems. Today, the emergent opportunities presented by DG

and smart grids put such historical imperatives under a

particularly interesting spotlight.

5

Prins's [14] highly stylistic piece was published in a special volume of

the journal Energy and Buildings on the social and cultural aspects of

cooling and was contested by a number of invited commentaries (the

commentaries and Prins's rejoinder can be found in volume 18, 1992, of

Energy and Buildings: 259–268).

The Lessons of History

As electricity grids grew rapidly in the early decades of the

twentieth century it became clear that optimal use of the

thermal generating plant then dominating supply provision

required significant additional loads, beyond those of

industry. As a result a number of energy service options were

174

developed reflecting, primarily, corporate, institutional, and

other professional preferences rather than those of consumers.

These were then aggressively marketed by those set to profit

from them. This provision and structuring of both energy

service options and of the means by which they might be

obtained were not therefore the result of unconstrained

consumer choice, as economic perspectives still tend to

assume, but rather gave the consumers exercising that choice

an ever-broadening range of services to choose from. The

current dominant suite of energy services and the means by

which they are delivered are thus as much a result of the

decisions and actions of utility managers, engineers, and

regulators as they are the result of the decisions and actions of

consumers. To characterize contemporary decisions regarding

these services as simply a straightforward matter of consumer

choice, with “choice” narrowly conceived as little more than

the responses of end-users to their own perceived needs,

electricity prices, and information is, therefore, misleading

and does not square with the empirical evidence. Some of the

most telling relevant contemporary examples are some of the

best known, such as the cheap off-peak, and highly inefficient

heat and hot water storage systems embedded throughout

centralized grid systems today. In other words the evidence

suggests that our current energy-intensive lifestyles are as

much about the systemic framing and conditioning of the

choices available to consumers as they are about the exercise

of individual consumer choice. Consequently, addressing this

systemic framing and conditioning of the choices available to

consumers requires that those currently responsible for

overseeing and delivering current energy provision reinstate a

substantive decision-making role for end-users.

175

Pressures for Change: Rising Demand, Energy

Security, and Climate Change

It is interesting to note that one of the stated objectives of the

electricity industry restructuring undertaken in numerous

countries over the last two decades was to facilitate customer

choice [16]. However, restructuring centering upon the

development of competitive electricity markets, and the

associated corporatization, or privatization, of previously

government-owned or regulated private monopoly industry

participants, has had mixed results in this regard. While

nominally focused upon improved efficiency, innovation, and

consumer choice there have been some highly counterfactual

outcomes such as the collapse of the Californian system, and

the experience of the energy user has not yet been markedly

changed in many cases (see, for example, [17]).

Now, however, current industry arrangements are under a

growing range of pressures that hinge critically, on the nature

and scale of desired energy services. They include growing

energy demand and particularly peak demand, rising energy

security concerns centering upon energy resource depletion

and the increasingly concentrated distribution of what

remains, and the threat of dangerous climate change.

Growing Demand

As documented in the previous section, growing demand has

been the normal state for the electricity industry since its

inception. While conventionally conceived as being driven by

aggregate growth in population and wealth, it was rather the

systemic intersection of this growth with the entrepreneurial

exploitation of emerging technological possibilities that has

176

been pivotal to growth in electricity demand. This remains the

case today; consumer electronics, for example, is a sector

particularly dynamic in proliferating new and/or augmented

energy services (e.g., flat screen TVs; gaming consoles with

enhanced functionality such as control via bodily movement;

ever greater integration and augmentation of the features of

hand-held digital devices, etc.), which is illustrated in Table

2.1 in terms of an ongoing growth in appliance penetration.

As a result end-users continue to find, and are indeed

encouraged to adopt, new energy services. Some of these,

such as air-conditioned homes and offices, require appliances

and equipment with high energy and, particularly, peak power

demands, and while there has been, and continues to be,

energy efficiency improvements, peak demand has been less

affected by these improvements. This steady growth in

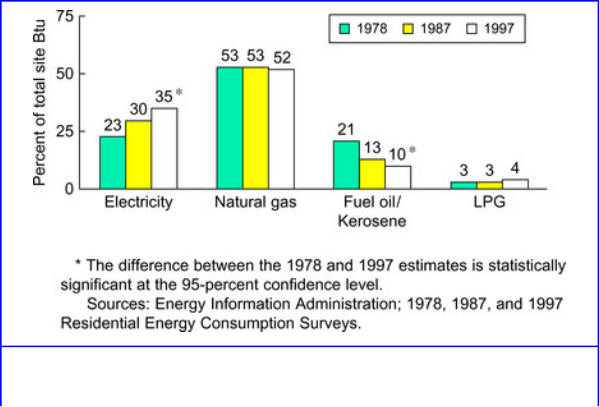

electricity demand, relative to other domestic energy sources,

is shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4

177

Percent of total U.S. residential site energy consumption by energy source.

The economics of end-user equipment has also changed with

respect to supply. For example, electric kettles can cost as

little as $10 while drawing 2 KW, and portable air

conditioners can now be purchased at a cost of around $300

while drawing 1KW. In addition, the electricity industry has

generally relied on diversity—that is on people not running

toasters or kettles at same time—yet air conditioning is

generally a highly correlated use. If your neighbor is running

their air-conditioning unit then there's a reasonable chance

you are running yours because use is driven by the weather.

On the supply side about the cheapest generation technology

available is the Open Cycle Gas Turbine at around $1000/KW

[18]—1 to 2 orders of magnitude greater expense per KW

than these electrical loads. Furthermore existing electrical

networks don't have low-capital cost-peaking options as seen

with generation (plants that are cheap to build but expensive

to run and, as a result, are better for infrequent peaks than

expensive to build but cheap to run baseload options). Many

industries around the world, including in Australia, spend

more on networks than on electricity generation. One result of

this is a potentially significant imbalance, with private

investment by end-users in particular new appliances

potentially requiring the supply side of the electricity industry

to invest equivalent levels in generation and network

infrastructure if reliability is to be maintained. Air

conditioning is a good case in point, having stressed some

local sub stations beyond capacity in recent years in the

authors’ hometown of Sydney [13, p. 5].

178

Energy Security

This has both short and longer-term dimensions. While the

longer term is focused upon concerns with primary-fuel

security, the short term is focused upon peak demand, which

tends to drive a longer term focus on investment in generation

and networks. The impact of the oil crisis in the early 1970s

provides an exemplary example of primary-fuel energy

security concerns in the electricity industry. Many countries

at the time had significant oil-fired generation, which is low

cost, easy to transport, and easy to use, and the 1970s price

shocks resulted in electricity industries globally turning to

alternatives. Some countries, France and Japan for example,

gave nuclear a significant role from this time, while the R&D

attention and funding this granted renewables, most notably

in the United States, significantly spurred the further

development of some renewable technologies such as PV and

wind. Furthermore, it had a very significant impact on

improving the energy efficiency of many countries.

In some ways the electricity industry has lower energy

security concerns than sectors like transport where

alternatives to oil are more limited. By comparison a very

wide range of potential primary energy sources can be turned

into electricity although the industry worldwide remains very

dependent on fossil fuels. Oil in particular and gas, to a lesser

extent, have likely constraints on supply in the near to

medium term, with likely upcoming price impacts. However,

the geopolitics of significant fossil fuel reserves is a

significant factor with more countries with gas than oil, for

example. Coal is far more abundant and geographically

dispersed but is also witnessing tightening demand and

179

increasing prices. However, the most pressing constraint on

fossil fuel use is that we cannot afford to continue to utilize

existing reserves as we have historically because of the

associated greenhouse emissions.

Climate Change

It currently appears that we will run out of an atmosphere

amenable to life as we know it before we run out of fossil

fuels. Figure 2.5 shows how 25% of global greenhouse

current gas emissions are from the electricity sector, primarily

coal, then gas, and then oil. It may be possible to continue to

use fossil fuels while restricting emissions through carbon

capture and storage technologies but these are proving to be

more difficult to develop into a viable working technology

than many proponents originally argued [18]. Climate change

is increasingly the driver of transformation, involving a range

of fundamental changes that move significantly beyond

traditional concerns with economics and reliability.

Figure 2.5

World greenhouse gas emissions by sector.

Source: http://maps.grida.no/go/graphic/world-greenhouse-gas-emissions-by-sector. Designer:

Emmanuelle Bournay, UNEP/GRID-Arendal.

Ultimately, climate science suggests a requirement for a near

complete decarbonization of energy supply by about

180