Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

acceptance. Go West Young Man (1937) and Every Day’s a Hol-

iday (1938) were rather boring—thanks to the Hays Office—

and offered none of West’s usual clever innuendos.

Paramount did not renew West’s contract, and the star

went to Universal to costar with W. C. Fields in My Little

Chickadee (1939). Though they made one of the screen’s

most interesting pairings, both West and Fields wrote their

own scripts, resulting in pure chaos when neither would

compromise.

West didn’t make another film until 1943 when she

starred in an independent feature, The Heat’s On. By that

point, however, she had become passé but not yet the appre-

ciated institution that she is today.

West was active in the 1940s and most of the 1950s on

Broadway, on tour, and in nightclubs, but then West

appeared to go into relative seclusion. That didn’t mean,

however, that she wasn’t in demand. She was approached for

roles in Sunset Boulevard (1950), The First Traveling Saleslady

(1956), Pal Joey (1957), and The Art of Love (1964), to name

just a few. Nothing came of those roles, but finally in 1970,

West returned to the screen, looking amazingly well pre-

served at the age of 78, in Myra Breckinridge. The movie was

an unmitigated bomb, but West was the best thing in the

film—and she wrote her own dialogue.

In 1978, she surprised Hollywood (and everyone else) by

starring in a movie based on one of her plays, called Sextette.

The movie was uneven at best. Although it featured an all-

star supporting cast, the film’s real appeal was as a curiosity

piece. However, few were interested in seeing an 85-year-old

woman make funny sexual remarks.

Toward the end of her life, many criticized Mae West for

being a living caricature of female sexuality, but one cannot

deny that her very flouting of societal strictures placed on

women was the key to her enormous success as a comedi-

enne. Indeed, her uninhibited interest in sex was a powerful

early warning shot of the feminist revolution.

See also

COMEDIANS AND COMEDIENNES

;

FIELDS

,

W

.

C

.

westerns A distinctly American genre that has been much

maligned. Although the western appears to be strictly formu-

laic, it is in fact enormously plastic, capable of being bent into

anything from morality tale to musical, from history lesson to

social criticism. It has been said that if westerns did not exist,

Hollywood would have had to invent them. Ironically, how-

ever, it was the other way around: Westerns invented Holly-

wood. After all, it was Cecil B. DeMille’s huge hit The Squaw

Man (1913), the first film shot there, that put the sleepy

southern California town on the map.

With their sweeping vistas, rousing chases, and dramatic

gun duels, westerns were perfect for outdoor filming and

ideal for the big screen. It did not hurt their case that such

films were inexpensive to produce (until recent decades) and

sure to please audiences smitten by the romance of the Amer-

ican West. In fact, horse operas became the most-often-

produced films in Hollywood history.

The western came into being even as the real West still

lived on in its fading glory. Indeed, William “Buffalo Bill”

Cody was seen on film at the very end of the 19th century.

Despite the fact that it was shot in New Jersey, the first true

western movie was Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery

(1903), a film that launched the genre with a vengeance. It

contained within its 10 minutes’ running time a great many

of the elements (some might call them clichés) of future

horse operas: a robbery, a chase on horseback, and a fierce

gun battle. It also had the bad guys getting their just deserts.

The western prospered during the silent era, becoming

standard fare for both children and adults with the emergence

of the first cowboy star, G. M. “Broncho Billy” Anderson, in

1908 in a film called Broncho Billy and the Baby. One of the big

changes in the genre wrought by Anderson was his filming on

location in the western United States—and audiences could

tell the difference between his stunning geography and the

grassy knolls of ordinary looking “eastern westerns.”

After Broncho Billy, William S. Hart was a top cowboy

star in the mid-1910s and early 1920s, raising the art of the

western with a gritty realism that made his movies, such as

Hell’s Hinges (1916) and Tumbleweeds (1925), genuine classics.

There were a great many popular western stars during

the latter half of the silent era, among them Ken Maynard,

Harry Carey, Fred Thompson, Tim McCoy, Buck Jones, and

Hoot Gibson, but the biggest western star of them all was

Tom Mix. During the late 1910s and throughout the rest of

the silent era, he was the number-one draw in western movies

and one of the most popular stars in Hollywood, with hits

such as The Cyclone (1920) and North of Hudson Bay (1924).

Mix’s films were marked by their nonstop action and lack of

realism. They were, however, full of incredible stunts.

Hollywood did not leave the western entirely in the

hands of cowboy stars, and many of Tinsel Town’s top direc-

tors worked in the genre as well, creating serious, big-budget

westerns. For instance, James Cruze made the hugely suc-

cessful The Covered Wagon (1923), followed by John Ford’s

earliest classic, The Iron Horse (1924).

The western appeared to be a casualty of the sound era

precisely because of its great, wide-open spaces; sensitive

sound equipment required talkies to be made in the studio.

However, as soon as the technical problems were solved, the

western reemerged with new popularity in films such as In Old

Arizona (1929), the first outdoor adventure film, and The Vir-

ginian (1929). Other important hits followed, such as Cimar-

ron (1931). Curiously, though, the big surge in westerns

throughout most of the rest of the decade occurred in low-

budget productions and serials. It was the era of, among oth-

ers, Bill Elliott, Kermit Maynard (Ken Maynard’s brother),

William Boyd, Rex Bell, George O’Brien, and Bob Steele, all

of whom made cheap, fast westerns that appealed to kids.

Even John Wayne was earning his spurs in quickie horse

operas and serials during the bulk of the 1930s. It was also

during this decade that the singing cowboy came into fashion

in the person of Gene Autry. It was not, however, a time when

westerns were taken seriously by the major studios.

Toward the end of the 1930s, however, the western sud-

denly shot back into prominence. With the world edging

closer to war, America began to look back at its heritage, its

values, searching for the spirit that made the nation great. The

WESTERNS

458

result were films such as Wells Fargo (1937), The Texans (1938),

Union Pacific (1939), and, most memorably, John Ford’s Stage-

coach (1939), the film that made John Wayne a major star.

The western became so popular near the end of the 1930s

that even a studio such as Warner Bros., bereft of anyone in

their stable resembling a westerner, nonetheless made films

such as The Oklahoma Kid (1939), with such distinctly mod-

ern and urban actors as

JAMES CAGNEY

and

HUMPHREY BOG

-

ART

. With considerably more success, Warners pressed

ERROL FLYNN

into service in several westerns, including the

impressive They Died with Their Boots On (1941).

With the outbreak of World War II, the western came to

an abrupt halt, replaced by its more immediate action/adven-

ture counterpart, the war movie.

When the war ended, the western entered its golden era,

a period that lasted for roughly 15 years. It began with (and

was sustained) by director John Ford, who returned to the

western with My Darling Clementine (1946). Ford went on to

make many of Hollywood’s most cherished westerns, includ-

ing Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and

The Searchers (1956). But he was hardly the only director

making horse operas during those years. Anthony Mann cast

star Jimmy Stewart in a series of excellent westerns such as

Bend of the River (1952), and Budd Boetticher teamed with

Randolph Scott to do the same in films like The Tall T (1957).

The 1950s boasted such highly praised and popular west-

erns as Shane (1953) and High Noon (1952), bringing critical

appreciation to the genre. As part and parcel of its new adult

patina, the western began to explore its darker side, admit-

ting the wrongs done to the Indians in films like Broken

Arrow (1950) and touching on psychological issues in movies

such as The Gunfighter (1950) and The Far Country (1955).

Even as the explosion of TV westerns during the later

1950s eroded the box-office appeal of big-screen horse

operas, movies such as Man of the West (1958), The Big Coun-

try (1958), The Left-Handed Gun (1958), and Rio Bravo (1959)

continued to grace movie screens.

The 1960s saw the decline of the genre. The western rep-

resented a simpler, positive image of America that the Viet-

nam War severely tarnished. It was as if filmmakers were

aware that this particular western cycle was near its end.

Movies about the closing of the West predominated, such as

John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and

Sam Peckinpah’s Ride the High Country (1962). By the mid-

1960s, the Western had nearly vanished as a viable major

moneymaker, only to reappear unexpectedly in the form of

the “spaghetti western,” spearheaded by Italian director Ser-

gio Leone and his film A Fistful of Dollars (1967), a movie that

awakened the western and catapulted Clint Eastwood to

international stardom.

By the end of the 1960s, westerns had returned briefly to

prominence with films such as the comedy Support Your Local

Sheriff (1969), Sam Peckinpah’s controversial masterpiece

The Wild Bunch (1969), and John Wayne’s Oscar-winner True

Grit (1969). Without doubt, 1969 was the latter-day high

point of this noble genre.

The 1970s saw several attempts at keeping the western

alive, chief among them Little Big Man (1970), Robert Alt-

man’s baroque McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971), Ulzana’s Raid

(1972), The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (1972), and John

Wayne’s last film, The Shootist (1976). With high production

costs, however, and little audience interest beyond the above-

mentioned films and the occasional Clint Eastwood vehicle,

such as The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), the western lan-

guished. It went into even further decline in the late 1970s

with the emergence of Star Wars (1977), a film that launched

science fiction as a new sort of frontier movie.

In more recent years, the genre almost disappeared. There

were only four major Hollywood attempts to revive it in the

1980s. The first was The Long Riders (1980), which received

good reviews but did lackluster business. In the middle of the

decade, Lawrence Kasdan wrote and directed Silverado (1985),

an ambitious movie that received mixed reviews and suffered

poor box office. It was followed a few years later by Young Guns

(1988), a

BRAT PACK

western starring, among others, Charlie

Sheen, Emilio Estevez, and

KIEFER SUTHERLAND

. The film

showed some power at the ticket windows but received poor

reviews from the critics. The only other genuinely successful

western made in Hollywood during the 1980s was Clint East-

wood’s star-powered Pale Rider (1985).

Although some thought the western was dead, some evi-

dence to the contrary surfaced during the 1990s. Clint East-

wood directed one of his very best films in Unforgiven

(1992), a postmodern western that deconstructed the

process of mythmaking in the American West. Eastwood

won an Oscar for his direction, and Gene Hackman won an

Oscar for his acting, proving that the western still had life

in it.

Another inventive western, Tombstone, directed by

George Cosmatos, was released in 1993, the year before

Kevin Costner’s Wyatt Earp was released, and a far more

clever movie. Tombstone beat the competition in several ways

but especially in casting Kurt Russell as Wyatt Earp and Val

Kilmer as Doc Holliday. In Wyatt Earp (1994), directed by

genre expert Lawrence Kasdan, Costner played the title role

and Dennis Quaid played Doc Holliday. What gave Tomb-

stone the edge was its savvy, revisionist postmodern approach

to the stuff of legend.

Even more impish was Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man (1995),

featuring William Blake (

JOHNNY DEPP

) and Nobody, a

Native American who is friendly to Depp because he has

read the poet William Blake. Blake is shot early in the film

and is therefore destined to become the “dead man” of the

title. Of course, earlier in the decade, Kevin Costner

directed the politically correct Oscar-winning Dances with

Wolves (1990), which paid tribute to the Lakota Sioux tribe

in the Dakotas.

Hollywood even brought back, 40 years later, some of the

television westerns of the 1950s. James Garner was somehow

still able to star in Maverick (1994), though the younger and

therefore sexier Mel Gibson assumed the role Garner had

played for years on television. In 1999, Barry Sonnenfeld

decided to exploit the talents of

WILL SMITH

, Kevin Kline, and

Kenneth Branagh by resurrecting another 1950s television

series, The Wild, Wild West, taking a sort of foot-in-mouth

approach to what had been a tongue-in-cheek western spoof.

WESTERNS

459

See also

ANDERSON

,

G

.

M

. “

BRONCHO BILLY

”;

AUTRY

,

GENE

;

BOETTICHER

,

BUDD

;

CANUTT

,

YAKIMA

;

COOPER

,

GARY

;

EASTWOOD

,

CLINT

;

FORD

,

JOHN

;

FULLER

,

SAMUEL

;

THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY

;

HART

,

WILLIAM S

.;

HATHAWAY

,

HENRY

;

HAWKS

,

HOWARD

;

KING

,

HENRY

;

KRAMER

,

STANLEY

;

LADD

,

ALAN

;

MANN

,

ANTHONY

;

MAYNARD

,

KEN

;

MCCREA

,

JOEL

;

MIX

,

TOM

;

MURPHY

,

AUDIE

;

PECKINPAH

,

SAM

;

REPUB

-

LIC PICTURES

;

RIN TIN TIN

;

ROGERS

,

ROY

;

SCOTT

,

RAN

-

DOLPH

;

STAGECOACH

;

STEWART

,

JAMES

;

WALSH

,

RAOUL

;

WAYNE

,

JOHN

.

Wexler, Haskell (1926– ) Known principally as a

gifted cinematographer, he is also a director, producer, and

screenwriter of fiercely held left-wing beliefs. As a cine-

matographer, Wexler has both successfully experimented

with the vivid immediacy of cinema verité and captured the

pictorial splendor of classic Hollywood high production

values.

Knowledgeable about filmmaking due to a fascination

with cameras as a teenager, Wexler spent a full decade mak-

ing industrial films before making the leap to Hollywood fea-

tures in the late 1950s. Along the way, though, he was the

cinematographer (and codirector) of such documentaries as

The Living City (1953). His big Hollywood break came with

The Savage Eye (1959), a successful low-budget drama that

was noted for Wexler’s strong documentary visual style.

Wexler’s reputation as a cinematographer grew with films

such as The Hoodlum Priest (1961), The Best Man (1964), and

The Loved One (1965), which he coproduced. He reached the

first of many plateaus, though, when he won his first Oscar

for Best Cinematography for his work in black-and-white in

Mike Nichols’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966).

It isn’t hard to see Wexler’s political and social beliefs if

one looks at the films upon which he has chosen to work,

such as In the Heat of the Night (1967), Bound for Glory (1976),

for which he won his second Academy Award for Best Cine-

matography, Coming Home (1978), No Nukes (1980), and

Matewan (1986). Still, even as he photographed his feature

films, Wexler also pursued his own personal projects, direct-

ing and photographing documentaries such as The Bus

(1965); Interviews with My Lai Veterans (1970), which won an

Oscar for Best Documentary; and Brazil: A Report on Torture

(1971), which he codirected with Saul Landau (with whom he

collaborated on yet another six documentaries made during

the next dozen years).

Wexler has enjoyed a long and prestigious career as a cin-

ematographer, working with the cream of Hollywood’s direc-

torial community. He has been associated with some of the

most important and memorable films of the 1970s, 1980s,

and 1990s, including

FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA

’s The Conver-

sation (1973),

GEORGE LUCAS

’s American Graffiti (1973),

Milos Forman’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Ter-

rence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978),

DENNIS HOPPER

’s Col-

ors (1987), Ron Shelton’s Blaze (1989), for which he received

an Oscar nomination for Best Cinematography, Norman

Jewison’s Other People’s Money (1991), and

JOHN SAYLES

’s The

Secret of Roan Inish (1994).

Wexler had dabbled as a feature-film director, writer,

photographer, and producer. His first project caused a con-

siderable flurry of attention when Wexler directed his

actors to improvise their scenes against the backdrop of the

actual riots outside the 1968 Democratic Convention in

Chicago. The resultant film, Medium Cool (1969), was a sur-

prise critical hit and a minor commercial success. Unfortu-

nately, Wexler didn’t direct another feature until Latino

(1985), another politically motivated film, this one about

the war in Nicaragua.

His work on Medium Cool was included in the documen-

tary Look Out, Haskell, It’s Real! The Making of “Medium Cool”

(2001), and he was one of the cinematographers interviewed

for the documentary Visions of Light: The Art of Cinematogra-

phy (1992). He was the first cinematographer in 35 years to

receive a star on Hollywood’s “Walk of Fame,” and he

received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American

Society of Cinematographers.

Whale, James (1896–1957) The director of four of

Hollywood’s greatest horror films of the 1930s, as well as

sophisticated romances, musicals, stage adaptations, and

adventure films. No matter what he directed in his 11 years

in Hollywood (1930–41), Whale brought to all of his films a

fluid camera style, a strong pictorial sense, a dash of humor,

and unrushed, confident pacing.

WEXLER, HASKELL

460

Haskell Wexler is certainly the most independent of con-

temporary cinematographers. He photographs only those

films in which he believes, and his reputation is such that he

is always in demand. This Oscar-winner has also directed

films, including a number of highly regarded documen-

taries.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF HASKELL WEXLER)

Born in England, Whale worked as a cartoonist before

discovering the joys of the theater in a most unlikely place: a

German prisoner-of-war camp. His jobs in the theater

evolved from actor to set designer to director during the

1920s. After he directed Journey’s End, a play about the First

World War, to rave reviews in London and New York, he was

invited to direct the screen version in Hollywood. Journey’s

End (1930), for Tiffany Productions, was his auspicious debut

as a movie director, and he followed it with the highly suc-

cessful romance Waterloo Bridge (1931) at Universal Pictures,

for which he made most of his movies. His reputation was

ultimately made with the classic horror film Frankenstein

(1931). During the next four years, he made three more clas-

sic horror movies, The Old Dark House (1932), The Invisible

Man (1933), and perhaps his most highly regarded achieve-

ment, The Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

Among his other well-known films were what many con-

sider the best version of the Jerome Kern/Oscar Hammer-

stein musical, Show Boat (1936), another adaptation from the

stage, The Great Garrick (1937), which he also produced, as

well as the rousing Alexander Dumas tale, The Man in the Iron

Mark (1939). In all, he directed 20 films, his last full-length

feature being They Dare Not Love (1941). Then, inexplicably,

he walked away from Hollywood to pursue his interest in

painting. In 1949, he briefly returned to filmmaking to direct

a segment of Hello Out There, an episodic movie that was

never released.

Whale’s death by drowning in his swimming pool under

eerie circumstances has never been adequately explained. Ian

McKellen played Whale in the Academy Award–winning Gods

and Monsters (1998), written and directed by Bill Condon.

See also

HORROR FILMS

.

White, Pearl (1889–1938) She was Hollywood’s most

famous serial star, an actress whose screen exploits kept

WHITE, PEARL

461

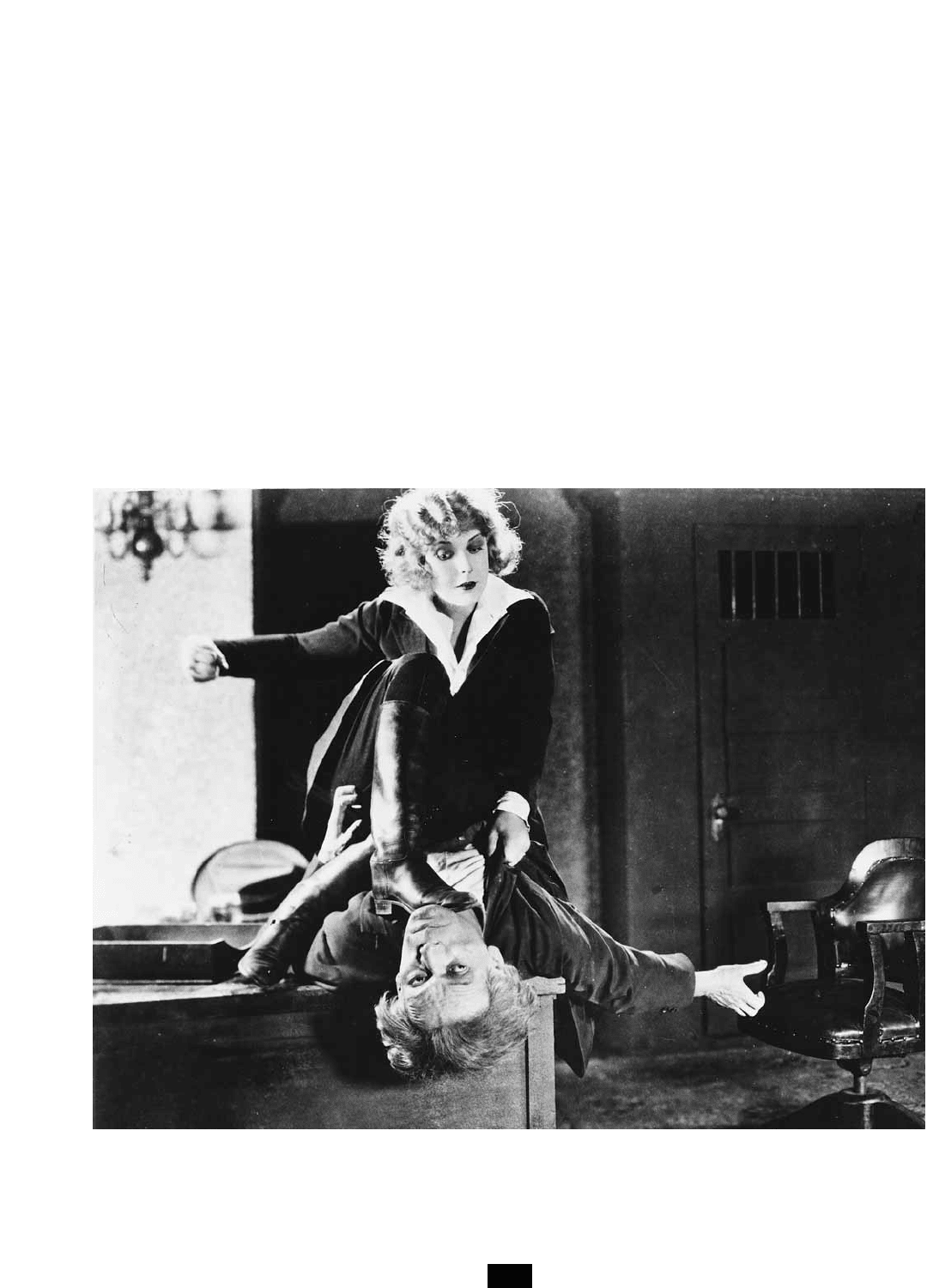

Hollywood’s most famous star of serials, Pearl White projected an entirely different image of femininity from little Mary

Pickford and ethereal Lillian Gish. She was shrewd, tough, and nobody’s fool—as the male actor underfoot could testify.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF THE SIEGEL COLLECTION)

audiences coming back every week for new installments of

her adventures. Pearl White was a forerunner of the eman-

cipated woman who didn’t necessarily need a man to solve

her problems; she solved mysteries and outwitted villains on

her own, giving women of the day a positive, if melodra-

matic, role model.

White began her show business career at six years of age

as Little Eva in one of the countless stock company produc-

tions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Later, she joined the circus but

hurt her back when thrown from a horse. It appeared as if her

show-business career was over when she became a secretary

in a small film company. But when an actress was unable to

perform, White was pressed into service to play the lead

female role in an ambitious three-reel film, The Life of Buffalo

Bill (1910). She continued acting, working often and receiv-

ing enough recognition to be included in the film title Pearl

as a Detective in 1913. It was the following year, however,

while working for Pathé, that film history was made when she

starred in The Perils of Pauline (1914), a title with which her

name has forever become associated. This serial, which per-

fected the “cliffhanger,” was a tremendous hit. Working

almost exclusively in serials such as The Exploits of Elaine

(1915), Pearl of the Army (1916), and The Fatal Ring (1917),

the attractive White soon became Hollywood’s greatest

female box-office draw as a crime solver in roles that

exploited her intelligence, daring, and athletic prowess.

By 1920, though, she yearned for the legitimacy of star-

dom in traditional feature-length films. She left Pathé and

signed with Fox, appearing in roughly a dozen films during a

three-year period without much success. Chastened, she

returned to Pathé and made a new serial, Plunder (1923), but

audiences were no longer interested in White. She left for

France and made her last serial, known in America as Perils of

Paris (1924). She retired in the French capital and never

made another movie.

See also

SERIALS

.

Widmark, Richard (1914–2002) An actor who played

both memorable villains and hardboiled heroes in movies

since 1947. A sharply angled facial structure and a growly

voice mostly limited his roles to male-oriented dramas such as

contemporary crime movies and westerns; he was not the typ-

ically romantic leading man. In more recent decades, Wid-

mark reached that level of authority as both an icon and an

actor where he found himself cast in movies as the general or

the president.

Widmark planned a career in law but found himself

drawn to the theater while attending Lake Forest College.

His stage work was so accomplished that he was asked to stay

on at his alma mater to teach drama after he graduated in

1936. He stayed two years, finally heading for New York in

1938 and starting out as a radio actor. Widmark branched out

into the theater during the 1940s and then was offered the

part of a sadistic, psychopathic killer for his first film role.

The movie was Kiss of Death (1947), and few actors have made

such a memorable debut, especially in a supporting perform-

ance. His cackling, high-pitched laugh as he murdered his

victims brought him a great deal of critical and audience

attention, as well as an Oscar nomination. On the down side,

however, he was temporarily typecast in similar roles.

Widmark appeared in a large number of rather poor films

throughout his career, which has somewhat diminished his rep-

utation. Nonetheless, his association with some of Hollywood’s

top directors (though rarely in their best films) contributed to

his longevity as a star. For instance, he worked with Henry

Hathaway in the enjoyable Down to the Sea in Ships (1949),

ELIA

KAZAN

in the hard-hitting Panic in the Streets (1950),

JOSEPH L

.

MANKIEWICZ

in the violent racial drama No Way Out (1950),

and twice with the redoubtable

SAMUEL FULLER

in two low-

budget films, the striking Pickup on South Street (1953) and the

disappointing Hell and High Water (1954). In addition, after

playing Jim Bowie in

JOHN WAYNE

’s version of The Alamo

(1960), Widmark became a latter-day member of the John

Ford stock company, starring in the great director’s lesser

efforts Two Rode Together (1961) and Cheyenne Autumn (1964).

Though he seemed to be on the downside of his career by

the mid-1960s, Widmark came through with a sterling per-

formance in the highly regarded The Bedford Incident (1965)

and then again in Madigan (1968), which later became the

basis of a short-lived 1972 TV series of the same name in

which Widmark starred.

The actor continued to appear in motion pictures in such

films as Murder on the Orient Express throughout the 1970s

and into the 1980s, more frequently in supporting and fea-

tured roles than as a star, but since the early 1970s, when he

starred in the miniseries Vanished (1971), he worked increas-

ingly in TV in lead roles, such as in the much-admired A

Gathering of Old Men (1987). Widmark appeared in two fea-

ture films in the 1990s, Texas Guns (1990), a gritty western;

and True Colors (1991), in which he had a supporting role.

Wilder, Billy (1906–2002) A writer, director, and pro-

ducer whose sharply cynical point of view was surprisingly

potent at the box office throughout much of his career. The

creator of both stark dramas and often bitter comedies,

Wilder was also honored by the Academy of Motion Picture

Arts and Sciences with a startling 20 Oscar nominations, 12

for his screenplay collaborations and eight as Best Director,

winning a total of six Oscars altogether. In recognition of his

achievements in a Hollywood career that began in 1933, the

governors of the academy bestowed the prestigious Irving

Thalberg Memorial Award on Wilder in 1988.

Born Samuel Wilder in Vienna, he was called Billy by his

mother who loved all things American and understood it to

be a popular name in this country. He came from a success-

ful upper-middle-class Jewish family and originally studied

for a career in law. After just one year of legal studies, though,

he decided to become a journalist, eventually becoming a

reporter for a major Berlin newspaper.

Wilder made his movie debut as a screenwriter as one of

five talented young men who collaborated on the famous

documentary Menschen am Sonntag/People on Sunday (1929),

cowriting the script with future Hollywood screenwriter

Curt Siodmark; the film was directed by two future Holly-

WIDMARK, RICHARD

462

wood filmmakers, Robert Siodmak and

EDGAR G

.

ULMER

.

Future director

FRED ZINNEMANN

was the cinematographer.

The film created quite a stir at the time of its release, and

Wilder went on to write a number of other screenplays and

provide stories for the German film company UFA, including

the highly successful Emil and the Detectives (1931).

Hitler’s rise to power in Germany in 1933 was Wilder’s

cue to flee. Later, he would learn that his entire family in

Austria had died in a concentration camp.

His first stop before coming to America was in Paris

where he cowrote and codirected his first film, Mauvaise

Graine (1933), starring the then 17-year-old Danielle Dar-

rieux. He would not direct a movie again until 1942.

After sweating out a difficult entry into the United States

in a Mexicali consul’s office in Mexico, he arrived in America

in 1933 broke, with little facility for the English language, yet

hoping to succeed in the film mecca of Hollywood. He

learned English from listening to baseball games on the radio

and going to the movies. In the meantime, he sold a story

idea that became Adorable (1933), and he went on to sell both

his stories and scripts (usually written in collaboration) as he

began to build a modest reputation.

His career suddenly went full throttle in 1938 when he

began his brilliant 12-year collaboration with screenwriter

Charles Brackett. They began with the clever, dark

ERNST

LUBITSCH

comedy Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife (1938) and pro-

ceeded to pen such other grand entertainments as Midnight

(1939), Ninotchka (1939), and Ball of Fire (1941).

Thanks to the likes of

PRESTON STURGES

and

JOHN

HUSTON

, who had opened the door for screenwriter-direc-

tors in the early 1940s, Wilder stepped forward to direct the

Wilder-Brackett comedy hit The Major and the Minor (1942).

In all their future collaborations, Wilder directed and Brack-

ett produced, and the pair found a formula for a number of

hard-hitting and provocative movies that have since become

classics, among them Five Graves to Cairo (1943), Double

Indemnity (1944), The Lost Weekend (1945), for which Wilder

won his first Best Director Oscar, A Foreign Affair (1948), and

Sunset Boulevard (1950), which brought him his second Best

Director Academy Award.

Sunset Boulevard was the last collaboration between Wilder

and Brackett, and it appeared as if the director might not sur-

vive the breakup. He wrote, produced, and directed the criti-

cally acclaimed financial flop Ace in the Hole (1951), which was

later retitled The Big Carnival. The film, starring

KIRK DOU

-

GLAS

, was so unredeemingly dark and cynical that audiences

were turned off by its bitter view. Wilder learned his lesson in

future films, softening the cynicism to make it more palatable,

which also had the effect of drawing critical complaints of

hypocrisy. Whether sugar coated or not, many of Wilder’s

films have still retained a rather harsh and cynical residue.

After Ace in the Hole, Wilder continued to write, direct,

and produce, recouping his reputation with a long string of

hits, including Stalag 17 (1953), Sabrina (1954), The Seven

Year Itch (1955), The Spirit of St. Louis (1957), and Witness for

the Prosecution (1958).

Wilder always seemed to work best, however, when he

wrote in collaboration, and some of his best work was yet to

come when he joined with I. A. L. Diamond to pen the

screenplays for such hits as Love in the Afternoon (1957), Some

Like It Hot (1959), The Apartment (1960), for which Wilder

won his third and last Best Director Oscar, One, Two, Three

(1961), Irma La Douce (1963), Kiss Me, Stupid (1964), and The

Fortune Cookie (1966).

Wilder and Diamond collaborated on all of the rest of

Wilder’s films, including his later work that received little

critical and commercial acceptance, including Fedora (1979),

and their last film together and Wilder’s last movie, Buddy,

Buddy (1981).

Just as Wilder worked with two screenwriters with excel-

lent results, so he consistently worked with a handful of

actors. Among those who appeared often in Wilder films

were

WILLIAM HOLDEN

,

SHIRLEY MACLAINE

,

WALTER

MATTHAU

, and, particularly,

JACK LEMMON

. Wilder died at

his Beverly Hills home on March 27, 2002.

Wilder, Gene (1935– ) A comic actor, screenwriter,

director, and producer whose personal style has been very

much in the

DANNY KAYE

tradition. Like Kaye, Wilder pos-

sesses a sweet innocence, and he has specialized in playing

nervous, inhibited characters who are forced by circumstance

into “outlandish” comic activities. At his best when buoyed

by the talents of other brilliant comic minds, Wilder has ben-

efited greatly from working in

MEL BROOKS

comedies and in

acting collaborations with

RICHARD PRYOR

. He has been less

successful behind the camera than in front of it, directing and

starring in five films with only modest success.

He was born Jerry Silberman to a Russian immigrant

father who became a wealthy manufacturer. Wilder’s interest

in acting was fanned at the University of Iowa, and he pursued

his studies after graduating by traveling to England to study at

the prestigious Old Vic Theatre School. He learned how to

fence while in England, using that skill to earn his living as a

fencing instructor when he returned to the United States.

Wilder continued his theater studies at the Actors Studio

while gaining experience first Off-Broadway and later on the

Great White Way. Still, he was a virtual unknown until he

made a splash in his seriocomic movie debut as a nervous

undertaker in Bonnie and Clyde (1967). It was a small but

memorable part, and it led to his starring role as Leo Bloom

opposite Zero Mostel’s Max Bialystock in Mel Brooks’s cult

favorite The Producers (1968). Wilder’s persona was estab-

lished in this film, and he was nominated for a Best Actor

Academy Award for his performance. Despite the fact that

The Producers was not an immediate box-office hit, it success-

fully launched Wilder’s career.

Blessed with an endearing charm that softens his some-

times screeching film antics, Wilder went on to display his

comic romanticism in films such as Quackser Fortune Has a

Cousin in the Bronx (1970) and Willy Wonka and the Chocolate

Factory (1971). His humor took a more bizarre turn under the

direction of

WOODY ALLEN

in the hilarious “Daisy” episode

of Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex But Were

Afraid to Ask (1972) when he played a psychiatrist in love with

a sheep.

WILDER, GENE

463

Mel Brooks finally turned Wilder into a major star in the

back-to-back hits Blazing Saddles (1974) and Young Franken-

stein (1974). Wilder also received credit for cowriting the

screenplay of the latter film, further enhancing his image as a

creative performer.

Emboldened by the experience of having been directed

by two comic actors, Allen and Brooks, Wilder took the

plunge and wrote, directed, and starred in his own film, The

Adventures of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother (1975). He has

gone on to write, direct, produce, and star in The World’s

Greatest Lover (1977), as well as write, direct, and star in his

own segment of the anthology film Sunday Lovers (1981). He

has also directed The Woman in Red (1984) and Haunted Hon-

eymoon (1986), both of which costarred his wife, comedienne

Gilda Radner.

Although his directorial efforts have met with mixed

results both with the critics and with film fans, he remains a

hot property thanks to his sterling performances in collabo-

ration with comedian Richard Pryor in such hits as Silver

Streak (1976), Stir Crazy (1980), and, to a lesser extent, See No

Evil, Hear No Evil (1989). He was also well received as a Pol-

ish rabbi in the offbeat comedy western The Frisco Kid (1979)

but flopped in Hanky Panky (1982).

During the latter half of the 1980s, he dropped out of

filmmaking to care for his ailing wife, who died of ovarian

cancer in 1989.

In the early 1990s, Wilder appeared in two disappointing

films, Funny about Love (1990) and Another You (1991), with

longtime sidekick Richard Pryor. The collaboration lacked the

spontaneity and the chemistry of their earlier films. Eight

years later, he attempted a comeback in a pathetic version of

Alice in Wonderland and the Joyce Chopra Murder in a Small

Town (both 1999). The comeback was not successful.

Williams, Esther (1923– ) She was one of a relative

handful of sports stars, including

BUSTER CRABBE

,

JOHNNY

WEISSMULLER

, and Sonja Henie, who had lasting careers on

the big screen. Despite her very limited ability as an actress,

Esther Williams was able to use her particular talent—swim-

ming—to great advantage. Her films were light entertain-

ments, and the mandatory water ballets managed to be

enjoyably campy. Also, it didn’t hurt that Williams looked

good in a bathing suit.

After becoming a swimming champion at the age of 15,

Williams went from part-time model and college student to

a featured member of Billy Rose’s Aquacade. MGM signed

her up and introduced her to movie audiences, as they had

JUDY GARLAND

,

LANA TURNER

, Kathryn Grayson, and

Donna Reed, in a modest role in an Andy Hardy movie, in

this case Andy Hardy’s Double Life (1942).

By 1944, MGM was ready to give Williams a shot at star-

dom, casting her as the lead in the musical comedy Bathing

Beauty. With its high production values, good-natured

humor, and slight escapist story line, the film was a happy

respite for a war-weary nation.

She followed her initial success with similar movies, such

as Thrill of a Romance (1945), This Time for Keeps (1946), and On

an Island with You (1947). Most of her movies were pleasantly

forgettable but eminently profitable for MGM. Undoubtedly,

the best movie of her career was Take Me Out to the Ballgame

(1949), but she was overshadowed by

GENE KELLY

and

FRANK

SINATRA

, despite a

BUSBY BERKELEY

water ballet.

The fundamental contrivance of having Williams near

(and in) a pool in all of her musicals made her formula a bit

taxing but also somewhat reassuring. In any event, movies

such as Neptune’s Daughter (1949), Million Dollar Mermaid

(1952), and Dangerous When Wet (1953) helped to make

Esther Williams a memorable figure in Hollywood lore.

After more than a decade of starring in aquatic musicals,

Williams dried herself off and tried to make the transition to

dramatic actress in The Unguarded Moment (1956). Audiences

weren’t interested, and, finally, after three more films, neither

was Williams. She retired after starring in a Spanish produc-

tion called The Magic Fountain in 1961.

Williams, John (1932– ) A composer of film scores

who, after writing music for movies for 15 years, suddenly

leaped to public prominence with a stunning display of pow-

WILLIAMS, ESTHER

464

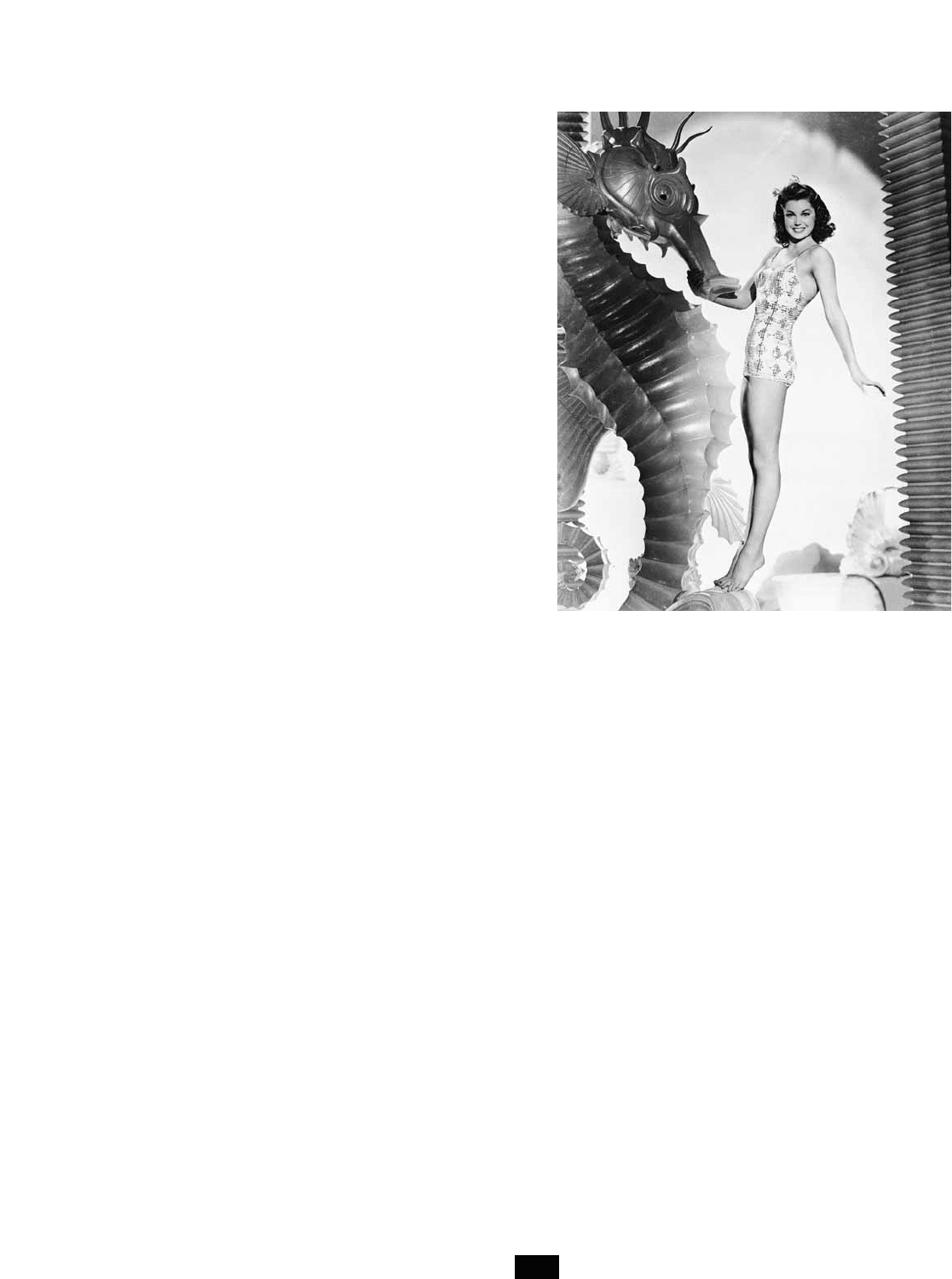

A champion swimming star in the late 1930s, Esther Williams

had perky good looks, a terrific figure, and a not immodest

talent. She scored throughout most of the 1940s and a good

chunk of the 1950s in a long string of MGM “wet musicals.”

(PHOTO COURTESY OF MOVIE STAR NEWS)

erful, thrilling musical creations for many of Hollywood’s

biggest hits of all time, including Jaws (1975), Star Wars

(1977), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), The Empire

Strikes Back (1980), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), and E.T. the

Extra-Terrestrial (1982). Williams’s contribution to these

films and many others unequivocably aided in their critical

and commercial success. From the shark’s theme in Jaws to

the musical notes used to communicate with the aliens in

Close Encounters, Williams’s musical signature is a vital factor

in the dramatic experience of a large number of the more

than 40 films on which he has worked.

John Towner Williams was born in Flushing, New York,

and received his early musical training at Juilliard before going

on to UCLA. Among the early films he scored were Because

They’re Young (1960), The Killers (1964), Valley of the Dolls

(1967), The Reivers (1969), Fiddler on the Roof (1971), for which

he was awarded an Oscar for musical arrangement, The Posei-

don Adventure (1972), and The Sugarland Express (1974). He

won Best Original Score Oscars for Jaws, Star Wars, Superman

(1978), The Empire Strikes Back, and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

Since 1980, Williams has been the conductor of the

famed Boston Pops Orchestra. This has not stopped him

from continuing to write music for the movies. He has

scored, among other films, Return of the Jedi (1983), Indiana

Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), The River (1985), The

Accidental Tourist (1988), and Indiana Jones and the Last Cru-

sade (1989).

From 1987 to the turn of the century, John Williams

received at least one Academy Award nomination every year

except 1994, although he won only once, for Schindler’s List

(1993). Some of his best work was done for Presumed Innocent

(1990). In 1993, in addition to the award-winning Schindler’s

List, Williams wrote the score for Jurassic Park, and both

soundtracks became best-sellers. After taking a year off,

Williams returned with Academy Award nominations for

Nixon and Sabrina (both 1995). Two years later, he wrote

scores for four important films in 1997: Seven Years in Tibet,

The Lost World, Rosewood, and Amistad; the last received

another Academy Award nomination. Williams had addi-

tional Academy Award nominations for Saving Private Ryan

(1998), Angela’s Ashes (1999), The Patriot (2000), Harry Potter

and the Sorcerer’s Stone and A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (2001),

and Catch Me If You Can (2002).

Arguably Hollywood’s finest musical talent, John Williams

has not only conducted the Boston Pops Orchestra but also

had his movie music honored by other symphony orchestras.

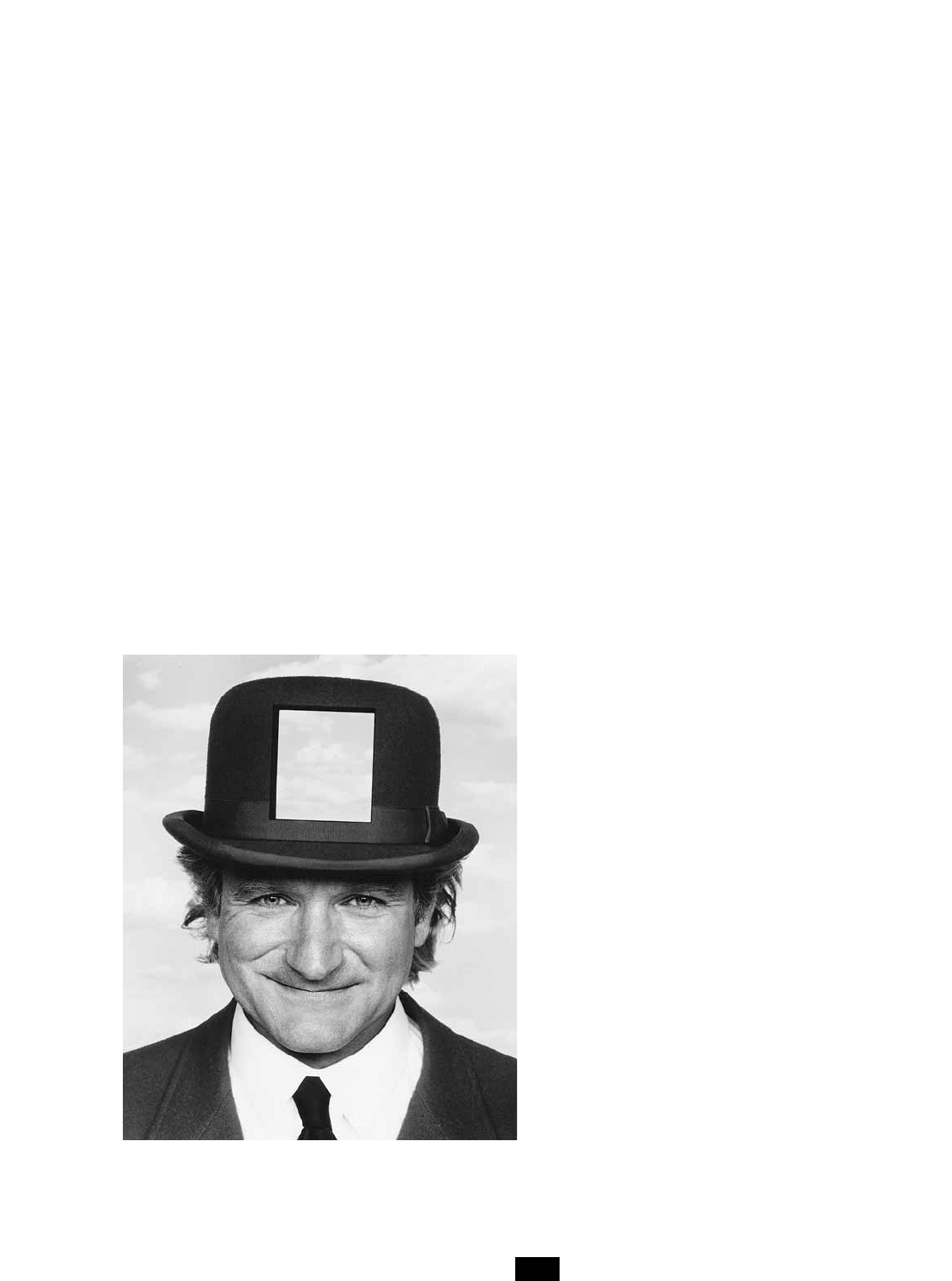

Williams, Robin (1952– ) Perhaps the most kinetic

and manic actor of his generation, Robin Williams is a veri-

table whirlwind of energy but one that requires the right cli-

mate or a firm directorial hand to harness his natural

exuberance. He has had an uneven career, even by Holly-

wood standards, winning awards for some roles and receiving

critical brickbats for others.

He was born July 21, 1952, to upper-middle-class parents

in Chicago, Illinois. Because his mother was a fashion model,

he was aware of show business from an early age. After grad-

uation from high school, he attended Claremont Men’s Col-

lege, where he majored in political science but found a home

in the theater. He moved to New York, where he studied act-

ing with

JOHN HOUSEMAN

at Juilliard, supporting himself by

performing pantomime, which prepared him for the physi-

cality of his performances.

Before he appeared in film, he was a stand-up comic and

a performer on The Richard Pryor Show. He got his big break

in 1977 when Garry Marshall cast him as Mork, the strange

alien in Mork and Mindy, a hit series. His first real feature was

Popeye (1980), which, despite his resemblance to the cartoon

character, was not a success, but he was favorably received as

Garp in the acclaimed The World According to Garp (1992).

His next noteworthy role was as Saigon disc jockey

Adrian Cronauer, a hyperactive character in Good Morning,

Vietnam (1987). He won a Golden Globe and was nominated

for an Oscar for his performance. His next role, that of an

idealistic prep-school English teacher in Dead Poets Society

(1989), stood in stark contrast and demonstrated his ability to

play serious roles. His performance won him another Oscar

nomination. After mediocre to bad reviews for his next few

films, he returned to form with The Fisher King (1991), in

which he played a street person with a Holy Grail fixation.

Despite the mix of medieval and modern, the film did win

WILLIAMS, ROBIN

465

Very few film composers are known to the general public,

but John Williams attained celebrity status for writing

scores for such hits as Jaws (1975), Star Wars (1977), Close

Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Superman (1978), Raiders

of the Lost Ark (1981).

(PHOTO COURTESY OF JOHN

WILLIAMS)

audiences, and Williams received his third Oscar nomina-

tion. Toys (1992) proved to be another wrong turn, but

Williams received a Golden Globe for his vocal work in the

animated feature Aladdin (1992) before capping his work with

a Golden Globe for his cross-dressing role as the nanny in

Mrs. Doubtfire (1993).

In 1994, when he was named “Funniest Man Alive” by

Entertainment Weekly and “Favorite Comedy Motion Picture

Actor” by People’s Choice Awards, he made Being Human,

which bombed, and the following year he was in Jumanji,

another mediocre film. The Birdcage (1995) was very success-

ful, with Williams playing the mellow half of a gay couple.

Nathan Lane won awards for his performance as the other

half, an outrageous drag queen, and Williams won the MTV

Movie Award for Best Comedic Performance (the sequence

in which he shows Lane how to walk like John Wayne is

hilarious). Lane and Williams also won the MTV Award for

Best On-Screen Duo. Although some critics were not

impressed by his performance as Professor Brainard in Flub-

ber, the 1997 remake of Disney’s The Absent-Minded Professor

(1961), he did receive the Blockbuster Entertainment Award

for Favorite Actor in a Family Movie. He won a more pres-

tigious award in 1998, the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor

for his role as the analyst who counsels troubled genius Will

Hunting in Good Will Hunting (1997).

In the title role in Patch Adams (1998), Williams managed

to combine his comedic and dramatic talents as the eccentric

physician who flouts the medical establishment and uses

humor as part of the healing process at his clinic. Once again,

some people (many put off by his over-the-top behavior)

faulted his portrayal of the real-life doctor, but there are

many devoted Williams fans who turn out to see him in

whatever film he appears.

Most recently, Williams gave voice to the character of Dr.

Know in Steven Spielberg’s A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (2001).

In Bicentennial Man (1999), he played Andrew, an android

who wants to be human. In Jakob the Liar (1999), Williams

played Jakob in this critically acclaimed World War II drama

set in Nazi-occupied Poland. He was highly praised. David

Hunter of the Hollywood Reporter considered this Williams’s

best film since Good Will Hunting.

Although Robin Williams appears to be a natural clown,

he has also provided evidence that he deserves to be taken

seriously as an actor, perhaps most convincingly in One Hour

Photo. Williams doesn’t wear a clown face this time, only the

sad, ordinary features of a lonely Everyman who desperately

needs human contact. Though a natural clown and gifted

stand-up comedian, Williams shows why his time spent with

the great John Houseman at Juilliard was worthwhile.

Willis, Bruce (1955– ) The high-energy, fast-talking

characters portrayed by Bruce Willis might have been created

by Damon Runyon or Raymond Chandler. This is all the

more remarkable, considering that Willis had to overcome a

problem with stuttering. He was born in West Germany,

where his father was stationed, but the family soon moved to

Carney’s Point in southern New Jersey. After high school, he

held a variety of jobs (such as security guard and truck driver)

before enrolling in Montclair State College, where he

appeared as Brick in the Tennessee Williams play Cat on a Hot

Tin Roof. In 1976, he made his professional acting debut in an

Off-Off Broadway production of Heaven and Earth.

His first break came in 1984 when he replaced the lead

in the Off-Broadway production of Sam Shepard’s Fool for

Love. Later that year, he was lucky (or talented) enough to

beat 3,000 competitors in auditioning for the role of David

Addison on the hit television series, Moonlighting, which

defined his initial popularity, as evidenced by an Emmy

Award and a Golden Globe Award. He was fortunate to be

cast opposite Cybill Shepherd, which provided an appealing

chemistry unusual for television, resembling the good-

natured bickering of William Powell and Myrna Loy in the

movies. This star-driven series was famous for its innova-

tions and fast dialogue.

After appearing in Blind Date (1987) and Sunset (1988),

both directed by Blake Edwards, Willis was cast in Die Hard

(1988), one of the highest-grossing blockbusters of the year.

Sequels would follow, but Willis avoided being typecast as a

macho maverick action hero like Schwarzenegger or Stallone

by appearing as the traumatized Vietnam War veteran in the

film adaptation of Bobbie Ann Mason’s novel In Country

(1989). In 1991 he played the lead in the cult comedy-adven-

ture Hudson Hawk (with Danny Aiello and Andie MacDow-

ell). The same year, he was also in Mortal Thoughts and Billy

WILLIS, BRUCE

466

Robin Williams in Toys (1992) (PHOTO COURTESY

TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX)