Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

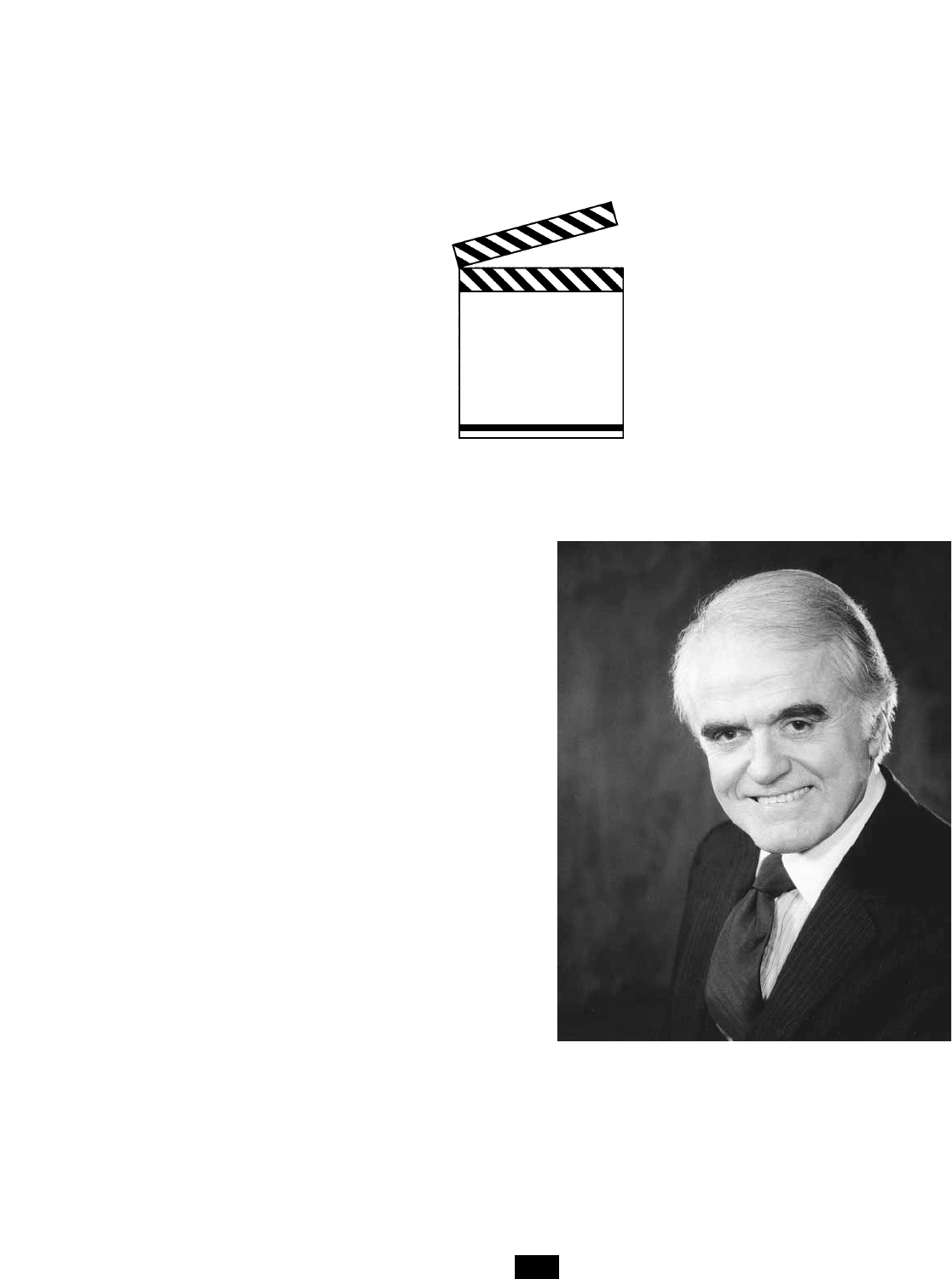

Valenti, Jack (1921– ) As president and chief execu-

tive officer of the Motion Picture Association of America,

Inc. (MPAA), the Motion Picture Export Association of

America, Inc., and the alliance of Motion Picture and Televi-

sion Producers, Inc., Valenti represents the interests of the

modern American film industry’s big eight: Columbia,

WALT

DISNEY

, MGM/UA, Orion, Paramount,

TWENTIETH CEN

-

TURY

–

FOX

, Universal, and

WARNER BROS

. As head of the

MPAA, he represents these companies as a unified front in

their dealings with the government and the public.

One of Valenti’s prime if less well-known responsibilities

as chairman of the Motion Picture Export Association is the

preservation and the enlargement of foreign markets, which

today account for slightly less than half of all U.S. film com-

pany revenues. It falls to him to negotiate film treaties and

settle difficult marketplace film issues with representatives of

more than 100 foreign governments on behalf of the eight

member film companies.

Since its founding in 1922 as the Motion Picture Produc-

ers and Distributors of America, only three men have served

as leaders of the MPAA: Will Hays (1922–45), who was post-

master general in the cabinet of President Harding (during

whose tenure the title movie czar was born); Eric Johnston

(1945–63), who was president of the United States Chamber

of Commerce; and Valenti, who began his duties in June

1966, leaving his post as special assistant to the president in

the administration of Lyndon Johnson.

Under Valenti’s leadership, the MPAA has substantially

relaxed the industry’s self-censorship practices, instituting a

helpful if maddening code that finds sex more objectionable

than violence.

Valenti’s latest cause involves copyright problems with

the Internet. He has been a staunch foe of unauthorized

copying in the entertainment field. For his efforts, he was

438

V

Jack Valenti is the longtime president of the Motion

Picture Association of America and is only the third

person to hold the post since it was created in 1922. His

office has been involved in developing the movie ratings

system as well as helping Hollywood producers sell their

films overseas.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF MOTION

PICTURE ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA, INC.)

made a life member of the Directors Guild of America and

has earned a star on Hollywood’s “Walk of Fame.”

See also

THE HAYS CODE

.

Valentino, Rudolph (1895–1926) The greatest male

movie sex symbol of the silent era and perhaps in the history

of the cinema. His brilliant career was highlighted by a hand-

ful of enormous box-office hits, hysterical fan reaction, and a

sudden, tragic end that turned him into a legendary figure.

He was christened Rodolfo Alfonzo Raffaele Pierre

Philibert Guglielmi di Valentino d’Antonguolla. His father, a

veterinarian in the Italian army, died when Valentino was 12

years old. Found unsuitable for officer training in either the

army or the navy, Valentino briefly pursued studies in agri-

culture. In the meantime, he was most successful as a spend-

thrift, depleting the family funds. As a consequence, he was

sent to New York to make his own way.

Valentino held a variety of jobs during his early years in

America, including that of a gardener. He also ran afoul of

the law, making extra money as a thief (with the rap sheet to

prove it). His most useful skill, however, was dancing. He

became a skilled exhibition dancer in New York’s club scene,

stealing the young

CLIFTON WEBB

’s partner, Bonnie Glass.

Valentino’s terpsichorean flair landed him in a musical

called The Masked Model that toured the country. He later

joined another stage musical in San Francisco. When that

show closed, he was broke and looking for opportunities

when one of his friends suggested he try the movie business

in Los Angeles.

Valentino made his movie debut as a dancer in a bit role

in Alimony (1918). He moved up (and sometimes down) the

cast list rather swiftly during the next three years in films

such as Delicious Little Devil (1919), A Rogue’s Romance (1919),

and Out of Luck (1919). He married for the first time during

these early years in Hollywood, but the union was extremely

short-lived. His wife, Jean Acker, locked him out of their

bedroom on their wedding night. The future great lover

never consummated his first marriage.

Valentino’s luck changed soon thereafter when he was

chosen by a perceptive Metro Pictures executive, June

Mathis, to star in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921).

The film became one of the top-grossing films of the 1920s,

earning more than $4.5 million.

Suddenly, Valentino was a hot property who hit a plateau

for the next few pictures and then zoomed even higher,

thanks to his famous performance in the title role of The

Sheik (1921). Women couldn’t get enough of him. An Ara-

bian craze hit the country, influencing everything from home

decoration to fashion. Valentino was the period’s epitome of

male sensuality; he was masculine yet vulnerable, fierce yet

tender, and thoroughly, unattainably exotic. Looking at his

films today, he seems rather silly and terribly overdramatic;

he was not a sensitive or subtle actor by any stretch. Many

men did indeed find Valentino effeminate and embarrassing,

but his legion of female fans made him a remarkably popular

star—until Valentino let his second wife, Natasha Rambova

(born Winifred Shaunessy), nearly ruin his career.

After Valentino’s star status was enhanced with Blood and

Sand (1922), Rambova insisted that he make The Young Rajah

(1922), a film over which she exerted a great deal of control.

It was a total disaster that threatened to turn Valentino’s

image into that of a hedonistic freak. She continued to wield

power over Valentino and was generally blamed for the dis-

appointing box-office performance of such films as A Sainted

Devil (1924) and Cobra (1925). Rambova continued to cos-

tume and make up Valentino in an embarrassingly girlish

manner and was responsible for interminable script changes

for which “Rudy” dutifully fought.

Finally, Rambova was contractually barred from interfer-

ing with Valentino’s next production. As a consolation, he

personally funded a picture of her own (What Price Beauty,

1925) that she then directed and produced. The movie failed

miserably, and she promptly left him.

Meanwhile, free of Rambova, Valentino regained his for-

mer glory in two towering hits, The Eagle (1925) and The Son

of the Sheik (1926), but the emotional and physical toll of his

stardom had been crushing. In 1926, he came down with a

perforated ulcer and was admitted to a hospital in New York.

The world was stunned when it was announced that

VALENTINO, RUDOLPH

439

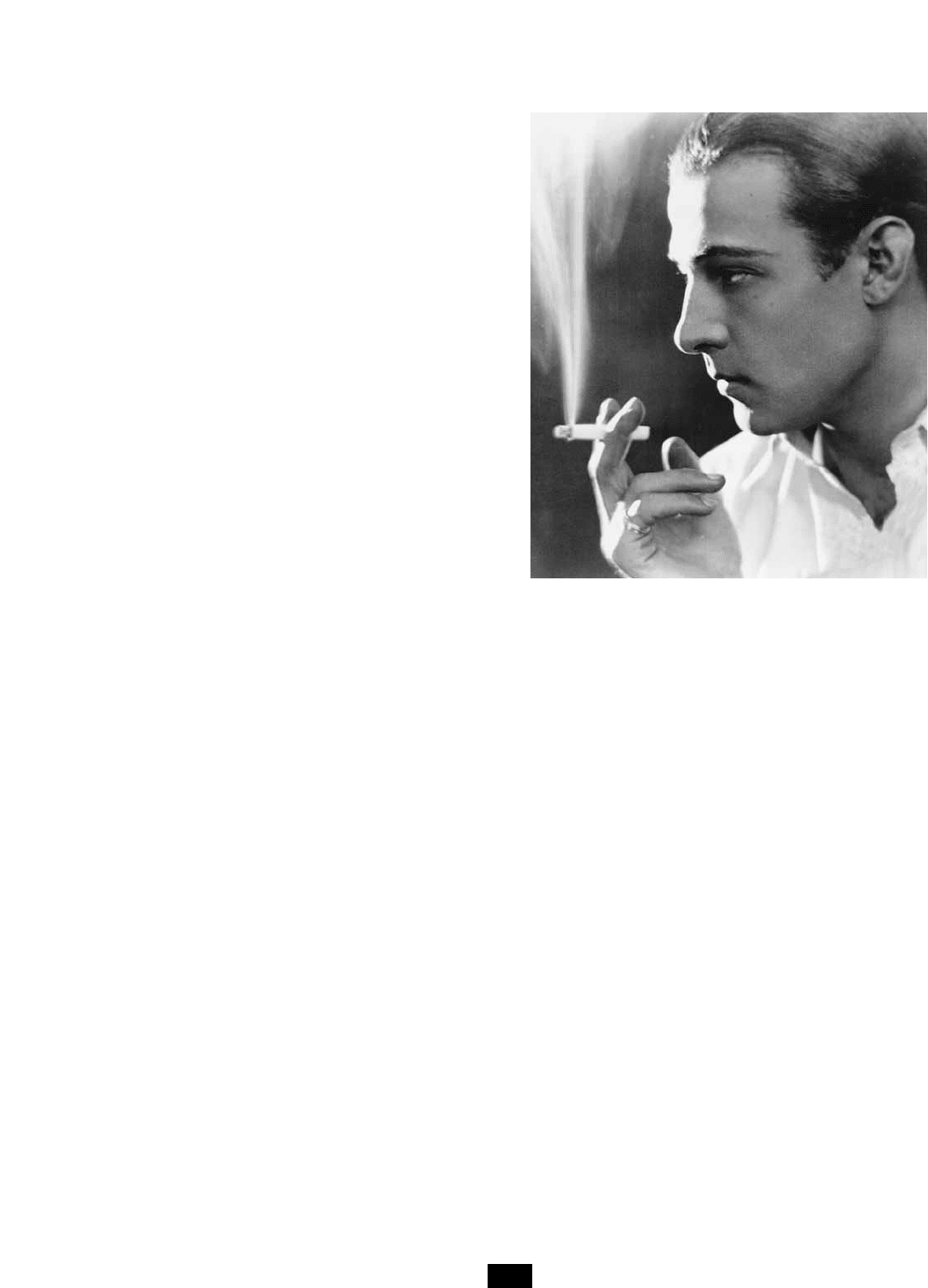

For many, Rudolph Valentino’s appeal to women seems

totally inexplicable, but his brooding intensity was utterly

magnetic in his day. He didn’t have a long period in vogue—

just five years—and his success almost certainly would have

ended with the coming of talkies, but he became a legend, in

large part because of his sudden, tragic death in 1926.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF THE SIEGEL COLLECTION)

Valentino had died. There were street riots in New York dur-

ing his funeral, and several women even committed suicide.

Valentino fan clubs lasted throughout the decades and his

image as a screen lover remains one of the enduring clichés

of the silent era.

As for Valentino, himself, he was reportedly a rather ordi-

nary man who found little happiness in his stardom. As he

once lamented, “A man should control his life. Mine is con-

trolling me.”

See also

SEX SYMBOLS

:

MALE

.

Van Sant, Gus (1952– ) Gus Van Sant was born in

Louisville, Kentucky, on July 24, 1952. His family later

moved to Connecticut and, eventually, to Portland, Oregon.

According to Tom Poe, “Van Sant became interested in film-

making at an early age and began making short Super-8 films

at the age of twelve. He continued making films as an art stu-

dent at the Rhode Island School of Design and, following

graduation, worked as a sound engineer for Roger Corman.”

Van Sant’s black-and-white film Mala Noche (1985), adapted

from the autobiographical novel by Walt Curtis, became a hit

at gay and lesbian film festivals.

A pioneer of the new queer cinema of the 1980s, Gus Van

Sant was the first openly gay director to become a main-

stream Hollywood filmmaker during the 1990s, as a result of

two “art-house” features, Drugstore Cowboy (1989), about a

band of 1970s dope fiends, and My Own Private Idaho (1991).

The latter film, inspired by

ORSON WELLES

’s Chimes at Mid-

night, restructured and updated the action of Welles’s Shake-

spearean compilation of the so-called Henriad (primarily the

plays King Henry IV, Parts I and II), moving it to contempo-

rary Portland, Oregon, where Van Sant lives and works. Just

as My Own Private Idaho was an homage to Welles, later in

the decade, Van Sant paid tribute to

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

in

his 1998 remake of Psycho (1960). As Tom Poe has written,

Van Sant “approached the task as if he had been given the

opportunity to restore rather than to re-make the classic film,

which he chose to film in color.” Van Sant’s Psycho was “a

remarkably faithful, even reverential reconstruction of the

original film, largely employing Hitchcock’s storyboards and

an only slightly augmented version of the original Bernard

Herrmann score.”

In his tribute to Orson Welles, Van Sant took far more

liberties with the text of Shakespeare and with Chimes at

Midnight. Welles had cited writing credits for Holinshead

and Shakespeare, but Van Sant credited himself as the

writer of My Own Private Idaho, though he also cited “addi-

tional dialogue by William Shakespeare.” After the critical

success of Drugstore Cowboy in 1989, Van Sant turned to two

screenplays that he had already written, combining a story

of street hustlers in Portland, Oregon, with his updated

adaptation of Henry IV and focusing, as Welles had done, on

the story of Shakespeare’s Falstaff. The result has been

called “Van Sanitized” Shakespeare, but, as Hugh Davis has

written, Van Sant’s “greatest inspiration is clearly and

admittedly Welles’s film, to which he is paying homage as

much as he is reviving Shakespeare.”

After the success of My Own Private Idaho, Van Sant’s career

faltered with his adaptation of the Tom Robbins novel Even

Cowgirls Get the Blues (1994) but rebounded the next year with

To Die For (1995). Adapted by Buck Henry from Joyce May-

nard’s novel, this film tells of a vapid housewife (

NICOLE KID

-

MAN

) who yearns to become a media celebrity. Even more

successful was Good Will Hunting (1997), scripted by actors

Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Van Sant’s Psycho, which fol-

lowed in 1998, was regarded as something of an oddity, but Van

Sant again recovered mainstream success with Finding Forrester

(2000), concerning the relationship between an African-Amer-

ican teenager and a reclusive writer played by

SEAN CONNERY

.

video assist The term applies to the recent practice of

simultaneously videotaping takes while shooting them on

film. Video, unlike film, doesn’t have to be developed before

one can see what has been shot. Therefore, recording a take

or a scene on video allows directors the opportunity to see

immediately if they like what they see or if they want to make

changes. The video assist is a helpful method of ensuring that

a scene works and will not have to be reshot after the set has

been struck. So far, video assists have been used mostly on

larger budget features, but it is reasonable to expect that the

practice will eventually widen to include all but the most

inexpensively produced films.

Vidor, King (1894–1982) Though born to a wealthy

Texas family, he was one of Hollywood’s most “European”

directors, as evidenced by both his fluid filmmaking style and

the often (if naive) political and social subject matter of his

movies. Most other American directors were content to make

a good, fast-paced, and entertaining film, but Vidor saw the

motion picture as an artistic medium early on. But his impres-

sive career, which spanned the 1920s through the 1950s, owed

as much to his American pragmatism as it did to his artistic

impulses. Vidor knew that his movies had to make money if

he was going to continue to direct, and, therefore, he only

rarely neglected the commercial realities of filmmaking.

Vidor’s early interest in film was born when he worked as

a projectionist in a Galveston movie theater. Fascinated with

the motion-picture medium, he started to make his own

newsreels in Texas as well as a comedy and an industrial film.

He married young Texas actress Florence Arto, and the two

set out for Hollywood in 1915. As Florence Vidor, his wife

went on to become a silent-screen star while he struggled to

find his own niche in the movie business. He worked as an

extra, tried to sell his scripts, and, after making a handful of

independent features, he put enough money together in 1920

to start his own shoestring studio, Vidor Village, and began

to make movies starring his wife.

Neither Vidor Village nor his marriage to Florence lasted.

The studio went out of business in 1922, and the marriage

ended in 1924. Meanwhile, the director had begun to work for

the Metro Company, which was soon melded into

METRO

-

GOLDWYN

-

MAYER

. Vidor made his big breakthrough, taking

what was intended to be a standard war yarn at MGM, The Big

VAN SANT, GUS

440

Parade (1925), and turning it into a powerful antiwar film and

one of the biggest hits of the silent era.

His reputation made, Vidor was in a position to pick and

choose his projects. Among his subsequent films was The

Crowd (1928), a stark and deeply cynical movie that dealt with

the loneliness and despair beneath the hustle and bustle of

America’s big cities. It was another major critical and box-

office hit for the director, and he was nominated for an Acad-

emy Award for Best Director.

Vidor took chances. He made Hallelujah in 1929 with an

all-black cast. Though the film was inadvertently racist in

many ways, his choice to deal with issues of race at all says a

great deal about his social conscience. Once again, the acad-

emy put him forward as a Best Director nominee.

As the studio system solidified during the early talkie era,

it became more and more difficult for a free-thinking director

like Vidor to make the kinds of movies that he yearned to put

on the screen. His skill was much in evidence in films such as

The Champ (1931), for which he won his third Oscar nomina-

tion for Best Director, and the brazenly erotic Bird of Paradise

(1932). But Vidor wanted to make Our Daily Bread (1934), a

film about farmer cooperation during the depression, and he

had to go outside the studio system, using his own money to

produce, write, and direct what has become an American clas-

sic. Justly famous for its climactic montage finale as the farm-

ers successfully irrigate their crops, Our Daily Bread left

Vidor’s bank account thoroughly parched. Although highly

regarded by many critics, it was a flop at the box office.

Henceforth, Vidor did not stray from the studio system,

although there was still a definite social and political point of

view in his work, most notably in Stella Dallas (1937); The

Citadel (1938), for which he garnered his fourth Oscar nomi-

nation; The Fountainhead (1949); and War and Peace (1955), for

which he received the last of his five Oscar nominations. He is

perhaps best remembered as the director of the sprawling epic

western Duel in the Sun (1946). His last film was Solomon and

Sheba (1959). All told, he directed 55 films, roughly half of

them with sound—but all of them with intelligence and style.

Though he never won an

ACADEMY AWARD

, Vidor was

awarded a special Oscar in 1979 for “his incomparable

achievements as a cinematic creator and innovator.”

Voight, Jon (1938– ) A complex and committed actor

who had his greatest screen success in the late 1960s and

1970s. Tall, blond, and blue-eyed, he has mostly shied away

from traditional leading-man roles to play characters who

live on the fringe of society.

The son of a golf pro, Voight intended to become either

a painter or a scenic designer but found his calling in the the-

ater while attending Catholic University, from which he

graduated in 1960. He went on to study acting at New York’s

Neighborhood Playhouse from 1960 to 1964, receiving both

emotional and financial support from his parents. As a result

of their generosity, Voight was able to avoid the actor’s alter-

nate profession of waiting on tables.

He had his first major break when he joined the Broad-

way cast of The Sound of Music as a replacement during that

hit show’s long run, playing the role of Rolf (and singing

“You Are Sixteen”) for six months. He received far more

attention from critics for his leading role in a revival of

Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge. As it happened,

DUSTIN HOFFMAN

was the assistant stage manager during

that show, and the two actors developed a mutual respect.

Later, Hoffman recommended Voight for the role of Joe

Buck in Midnight Cowboy (1969), turning his friend into an

Oscar nominee and a star virtually overnight.

Midnight Cowboy, however, was not Voight’s first film role.

After acting in stock and on TV, he made his movie debut in

Hour of the Gun (1967). Among other earlier films, he also

worked with Hoffman in Madigan’s Millions, a movie that was

made in 1967 before either of them were stars and finally

released in 1970 when they were both hot properties.

Voight’s film choices during his career have often

reflected his liberal and socially conscious beliefs; from the

very beginning, he has been rather picky about his movie

roles. As a consequence, he hasn’t appeared on screen quite

as often as he might have. He found his work in the 1970s,

with magnificent performances in Deliverance (1972) and

Coming Home (1978), winning an Oscar for his performance

as a paraplegic Vietnam veteran in the latter film. He was also

quite winning in some extremely mediocre movies, including

the counterculture exploitation movie The Revolutionary

(1970), the sentimental Conrack (1974), and the even more

sentimental The Champ (1979).

He continued to work in films during the 1980s but with

considerably less success. His best-known movie of the 1980s

was Runaway Train (1985), in which he and Eric Roberts

wowed the critics with their over-the-top performances.

Most of his other films of the 1980s, such as Lookin’ to Get

Out (1982) and Table for Five (1983), received mediocre

reviews and did little business at the box office. He was little

seen on the screen in the late 1980s.

Voight regained prominence as a skilled character actor

during the 1990s as a result of a great variety of roles, such as

the obsessed football coach in Varsity Blues (1999), helping

that film to earn $52 million, and as Jim Phelps in

BRIAN DE

PALMA

’s Mission Impossible, which earned more than $180 mil-

lion. Voight specialized in playing distinctive villains, such as

the ruthless government thug in Enemy of the State (1998). In

1997, Voight was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for

Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of a crooked insur-

ance company executive in John Grisham’s The Rainmaker.

That same year, he also appeared in U-Turn and Anaconda. In

the war epic Pearl Harbor, Voight played President Franklin

Delano Roosevelt, but his most convincing portrayal of a

real-life character was his role as Howard Cosell in Ali

(2001), which justly earned him a Golden Globe nomination

for Best Supporting Actor.

Von Sternberg, Josef See

STERNBERG

,

JOSEF VON

.

VON STERNBERG, JOSEF

441

Wald, Jerry (1911–1962) He was a screenwriter and a

producer who many believe to be the model for Budd Schul-

berg’s title character in What Makes Sammy Run? Ambitious

and energetic, Wald had a keen eye for the commercial

aspects of filmmaking. In a career that spanned 30 very active

years, he collaborated on the screenplays of many of

WARNER

BROS

.’ better films of the late 1930s and early 1940s and then

produced a sizeable percentage of that studio’s biggest hits in

the mid- to late 1940s. In the 1950s and beyond, when stu-

dios floundered in their search for a winning formula at the

box office, Wald continued to find commercial success right

up until (and after) his death.

Wald wrote about radio when he began his career as a

journalist. Not long after, in 1933, he parlayed his knowledge

into a string of short subjects for Warner Bros. starring radio

personalities. Impressed with young Wald, the studio hired

him as a screenwriter. He earned credits on mediocre films

such as Gift of Gab (1934) as well as some of Warner’s better

films such as Brother Rat (1938), The Roaring Twenties (1939),

Torrid Zone (1940), and They Drive By Night (1940).

When he turned producer in 1942, he started with minor

HUMPHREY BOGART

films that did well at the box office,

including All Through the Night (1942), Across the Pacific

(1942), and Action in the North Atlantic (1943). His success

with these war films led him to bigger budget efforts includ-

ing Destination Tokyo (1944) and Objective Burma (1945).

Wald came into his own as a Warners producer in the

mid-1940s when he found the winning formula for popular

women’s films. In a memo, taken here from the fascinating

book Inside Warner Bros. (1935–1951) by Rudy Behlmer, Wald

wrote to his immediate boss, Steve Trilling, “When are you

going to get wise to the fact that you can tell a corny story,

with basic human values, in a very slick, dressed-up fashion?”

Wald put his theories to the test in films such as Mildred Pierce

(1945), Humoresque (1946), Possessed (1947), Johnny Belinda

(1948), and Flamingo Road (1949) with huge success. In addi-

tion, he produced such strong and moody action movies as

Dark Passage (1947) and Key Largo (1948). As a result of his

stunning track record during the latter half of the 1940s, Wald

was presented with the Irving Thalberg Award in 1948.

Except for a brief stint as vice president in charge of pro-

duction at Columbia between 1953 and 1956, Wald pro-

duced as an independent. He didn’t lose his golden touch.

Among the films that bore the imprint of Jerry Wald Pro-

ductions were Peyton Place (1957), The Long Hot Summer

(1958), Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation (1962), and the posthu-

mously released The Stripper (1963).

Wallis, Hal B. (1899–1986) A producer and studio

executive, involved in the making of more than 400 movies,

a great many of which are now considered classics. In a

career spanning nearly 50 years, he first made his mark at

WARNER BROS

. as their executive in charge of production

during the broadest stretch of the studio’s golden years. He

then formed his own company, Hal Wallis Productions,

earning a reputation as one of Hollywood’s most successful

independent producers.

Born Harold Brent Wallis to a poor Chicago family, he

held a series of unmemorable jobs before moving to Los

Angeles in 1922. In that same year, Wallis became the man-

ager of the Garrick Theater, a major movie house, a job that

led to his being hired in 1923 as a publicity man for Warner

Bros. As Warners grew, so did Wallis’s responsibilities. He

became studio manager in 1928 and then head of production

for a short while. Between 1931 and 1933, he was supplanted

by

DARRYL F

.

ZANUCK

, but from 1933 until 1944, Wallis was

JACK L

.

WARNER

’s right-hand man.

During his stewardship at Warners, Wallis was responsi-

ble for some of the studio’s most memorable films, and his

442

W

name was boldly included in the credits of such films as Lit-

tle Caesar (1930), Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), Captain Blood

(1935), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), Dark Victory

(1939), The Maltese Falcon (1941), Yankee Doodle Dandy

(1942), and Casablanca (1942). His efforts at Warner Bros.

were appreciated by his peers, who honored him twice with

the Irving Thalberg Award, first in 1938 and then in 1943.

Jack Warner and Hal Wallis had a falling out in 1944, and

the producer formed his own production company, releasing

his films through Paramount, an association that lasted for 25

years. He was even more commercially successful as an inde-

pendent than he was at Warners, producing the enormously

popular Martin and Lewis comedies as well as Elvis Presley’s

musicals. He also brought challenging theater works to the

screen, producing, among others, Come Back, Little Sheba

(1952), The Rose Tattoo (1955), The Rainmaker (1956), and

Becket (1964).

Wallis finally changed his allegiance in 1969 to Universal,

producing such films as Anne of a Thousand Days (1969), True

Grit (1969), and his last movie, Rooster Cogburn (1975).

Walsh, Raoul (1887–1980) Hollywood’s premier out-

door action director, Walsh’s work is characterized by visual

economy and a strong masculine image, the latter quality

allowing him to inject a surprising amount of tenderness

and warmth into scenes that lesser directors would never

have dared.

Walsh was born to a well-to-do New York City family.

His father was an Irish builder, and his mother was of Span-

ish descent. Despite the comforts of home and a few years at

a couple of different colleges, including Seton Hall, young

Walsh gave in to his adventurous spirit and ran off to Texas

to punch cattle. After a horse fell on his leg, however, the

young man’s interests turned to the theater, and he estab-

lished an acting career. Walsh began to appear in one-reel

westerns as a villain in 1909 and soon began to study the

action behind the camera, becoming an assistant director for

D

.

W

.

GRIFFITH

in 1912.

He began to direct in 1914 with The Double Knot, but he

also continued to act throughout the silent era. As a director,

he often made movies that starred his younger brother, the

silent movie star George Walsh (1892–1981). Raoul’s most

famous acting role was as John Wilkes Booth in Griffith’s The

Birth of a Nation (1915).

A pivotal moment in Walsh’s career as a Hollywood

director occurred in 1920 when he made a serious and artis-

tic film called Evangeline. As Kingsley Canham reports in his

book, The Hollywood Professionals, Walsh’s experience with the

film was anything but gratifying. Walsh said, “Evangeline got

the most wonderful write-ups of any picture I ever made.

There were editorials written about it. But it didn’t make a

quarter. So I decided then to play to Main Street and to hell

with art.”

Despite his decision, Walsh had only sporadic success

during the early 1920s, but he hit his stride with one of the

greatest adventure epics of all time when he directed the

Douglas Fairbanks classic The Thief of Bagdad (1924). He

soon followed it with yet another hit, the male-bonding film

What Price Glory? (1926), which introduced the military char-

acters Flagg and Quirt to big-screen audiences. Walsh went

on to direct several popular sequels.

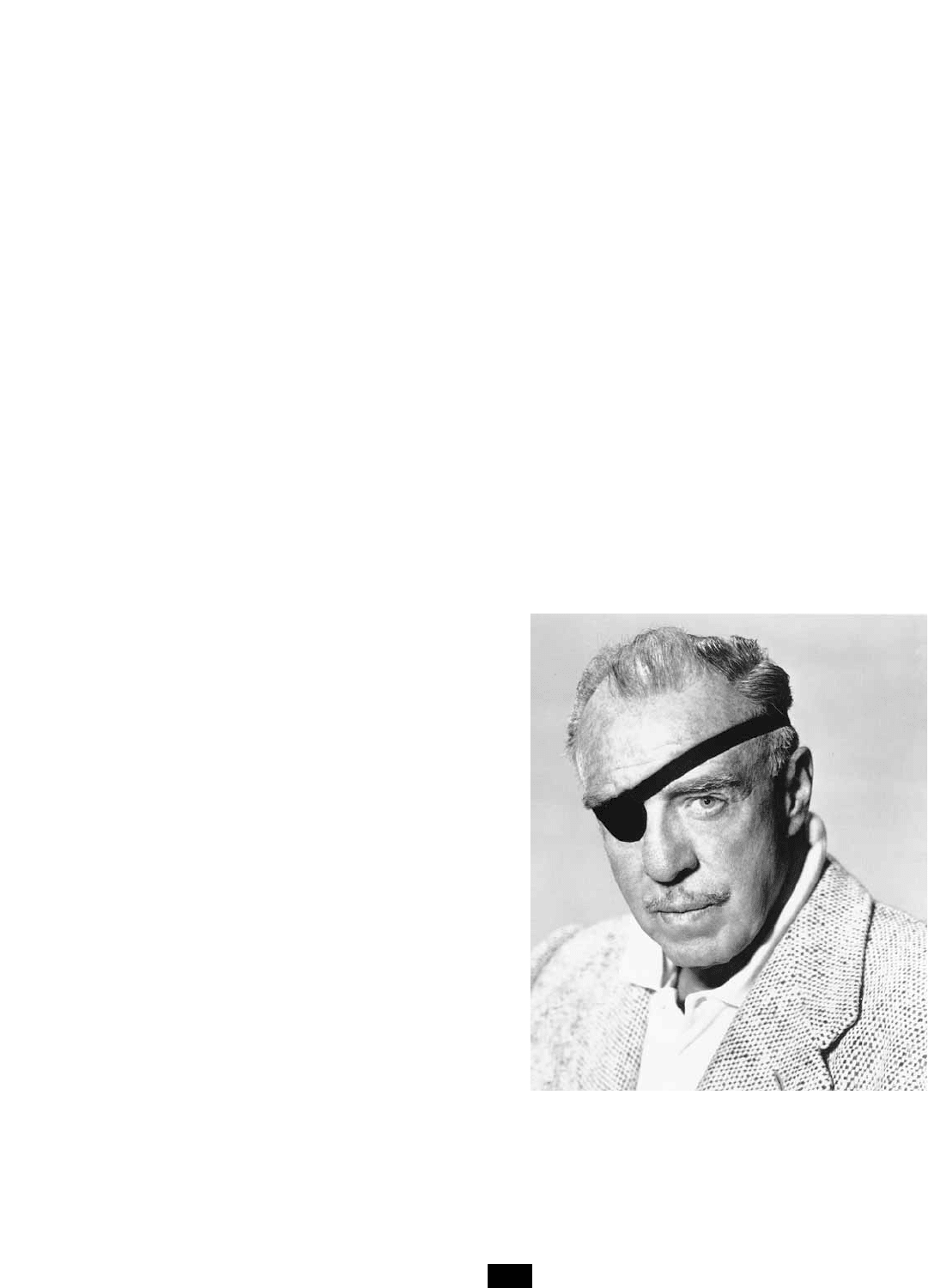

While making In Old Arizona (1929), a film which Walsh

was supposed to direct as well as star in as the Cisco Kid, he

was involved in a traffic accident and lost his right eye. The

distinctive patch that Walsh wore for the rest of his life added

to his mystique but ended his acting career. Warner Baxter

took over Walsh’s role in that film and ironically won an

Oscar as Best Actor, making him a major star.

Throughout the 1930s Walsh worked steadily, though his

skills as an action director were rarely put to good use. He

directed a few notable comedies, such as

MAE WEST

’s

Klondike Annie (1935) and

JACK BENNY

’s Artists and Models

(1937), as well as a number of light adventure films and

romantic comedies, but there was nothing special about his

work until he hooked up with Warner Bros. in 1939, direct-

ing Cagney and Bogart in The Roaring Twenties.

Warner Bros. was the perfect studio for Walsh’s tough,

male-oriented action films. In addition to the second half of

the 1920s, Walsh’s golden period as a director was the decade

between his two greatest gangster films, The Roaring Twenties

and White Heat (1949).

WALSH, RAOUL

443

Raoul Walsh began his film career as an actor but lost his

right eye in a traffic accident during the making of In Old

Arizona (1929). He then settled for becoming one of the

most respected action directors in Hollywood.

(PHOTO

COURTESY OF MOVIE STAR NEWS)

Despite a directorial career that spanned 50 years, the

movies for which Walsh is best remembered today are the

ones that starred

ERROL FLYNN

,

HUMPHREY BOGART

, and

JAMES CAGNEY

. They epitomized Walsh’s ideal of men of

action, and he directed them with panache.

Though it was director

MICHAEL CURTIZ

who made

Errol Flynn a star in Captain Blood (1935) and then guided his

career throughout the rest of the 1930s, it was Walsh who

sustained Flynn’s career, directing the actor in seven films,

among them one of Walsh’s greatest achievements, They Died

with Their Boots On (1941), as well as Gentleman Jim (1942)

and Objective Burma! (1945). Walsh also helped Bogart to

become a star when he directed him in They Drive by Night

(1940) and High Sierra (1941). As for Cagney, Walsh directed

the pugnacious actor in some of his best vehicles, including

The Strawberry Blonde (1941) and White Heat (1949). Of the

latter film, it has often been said that Walsh was the only

director in Hollywood who could have gotten away with a

scene that had Cagney sitting on his mother’s lap.

Walsh worked consistently throughout the 1950s, but it

was a period of slow decline for the aging director. He made

mostly mediocre westerns and war movies during the decade.

One of his more interesting projects, however, was a noble

attempt at bringing Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead

to the screen in 1958.

His last film was a minor western with Troy Donahue

called A Distant Trumpet (1964). He retired when his one

good eye began to fail him and he could no longer see well

enough to direct.

Wanger, Walter (1894–1968) In a career that spanned

five decades, he began as a producer and quickly rose to chief

of production at three of Hollywood’s biggest studios, Para-

mount, Columbia, and MGM. Wanger made all sorts of films,

from elegant romances to action films—usually with “A”

movie budgets. In the 1950s, he became an independent, suc-

cessfully producing some of the film industry’s most memo-

rable “B” movies.

Born Walter Feuchtwanger, the future producer seemed

destined for a career in Washington rather than Hollywood.

After graduating from Dartmouth College (followed by a short

stint as a producer on Broadway in 1917), he joined the war

effort as an officer in Army Intelligence. When World War I

ended, he joined President Woodrow Wilson’s staff, assisting

the statesman in his struggle to establish the League of

Nations. Perhaps disillusioned by his experience at the desul-

tory Paris Peace Conference, Wanger returned to the United

States and began his career as a producer at Paramount.

In Wanger’s long career, he was responsible for such films

as the

MARX BROTHERS

’ first effort, The Cocoanuts (1929),

one of Garbo’s most memorable movies, Queen Christina

(1933), Frank Borzage’s much-admired romance History Is

Made at Night (1937),

JOHN FORD

’s classic western Stagecoach

(1939) (for which Wanger served as executive producer),

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

’s excellent Foreign Correspondent (1940),

and

FRITZ LANG

’s clever Scarlet Street (1943), for which

Wanger, again, acted as executive producer.

His career slid in the late 1940s and early 1950s when he

produced a series of mediocre pictures and box-office duds.

Worse, still, he was involved in a major scandal when he was

arrested and convicted for shooting and wounding the agent

of his wife, actress Joan Bennett. A short jail sentence for

Wanger resulted.

In the mid-1950s, while working as an independent and

releasing through

UNITED ARTISTS

, Wanger proved that he

was not finished in show business when he produced two of

Donald Siegel’s and Hollywood’s best “B” movies of the

decade, Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954) and Invasion of the Body

Snatchers (1956). After yet another success with the hit I Want

to Live! (1958), Wanger stumbled badly when he was hired to

produce

CLEOPATRA

(1963). The production ran heavily over

budget, and Wanger was replaced by

DARRYL F

.

ZANUCK

.

The imbroglio effectively ended the producer’s career.

war movies A major genre that has ebbed and flowed in

popularity since the days of the nickelodeon. The very first war

movie, Tearing Down the Flag (1898), was so popular that it

caused a rush on the penny arcades that featured it. But it was-

n’t until the unprecedented success of

D

.

W

.

GRIFFITH

’

S THE

BIRTH OF A NATION

(1915), which contained scenes of Civil

War battles on a grand scale, that filmmakers woke up to the

inherent cinematic and dramatic possibilities of war movies.

America’s involvement in “the war to end all wars” in

1917 helped spur interest in the war-movie genre. World

War I spawned its share of blatant propaganda films such as

The Kaiser: The Beast of Berlin (1918) and Heart of Humanity

(1918), but it also inspired its share of thoughtful films, such

as Griffith’s much admired Hearts of the World (1918), which

contained actual battle footage shot by Griffith in Europe.

For the most part, however, the film industry would

approach World War I as a serious subject for film only after

sufficient time had passed to allow audiences some emotional

distance and a period of reflection. Interestingly, this pattern

of reticence followed by renewed interest in war movies

would repeat itself in Hollywood after each successive Amer-

ican armed conflict.

The first major film examining issues of World War I

opened seven years after the war’s end. King Vidor’s classic

The Big Parade (1925) was the first film to give a truly realis-

tic sense of war and its terrible cost. On the one hand, the

battle sequences in the film were exciting and thrilling, seem-

ingly glorifying war, but the film’s message was finally and

firmly antiwar because the audience saw the aftermath of the

battles as well.

Service comedies aside, The Big Parade set the standard

for most World War I films that followed, such as All Quiet

on the Western Front (1930) The Dawn Patrol (1930, and its

remake, 1938), and Today We Live (1933). All dramatized a

loss of innocence among soldiers, pilots, and sailors and were

permeated by a general sense of wasted youth.

The Hollywood World War I movie began to change

just before America’s entry into World War II, as the movie

studios readied the public for the new conflict to come.

Films such as The Fighting 69th (1940) and Sergeant York

WANGER, WALTER

444

(1941) extolled the heroism of the fighting man and, if not

glorifying war, inferred that there are times when it is nec-

essary to fight.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and America

joined the war effort, Hollywood and the U.S. government

became partners in filmmaking. According to Clayton R.

Koppes and Gregory D. Black in their informative book,

Hollywood Goes to War, the Office of War Information had a

profound impact on what war movies Hollywood made and

how they made them. Government officials actually partici-

pated in story conferences and wrote speeches mouthed by

actors in many a war film. Of course, World War II was seen

as a total war, and Hollywood, including most studios, writ-

ers, directors, and stars, was more than pleased to cooperate

with the government.

The significant themes that began to emerge in many of

the World War II movies were brotherhood, unity for the

good of the cause, and sacrifice.

For the first time in Hollywood history, a cross section of

ethnic groups could be found in the movies, with all of the

characters of the representative groups acting as heroes. It

quickly became a cliché that each cinematic combat unit con-

tain one Italian, one Jew, and one black. But this formula

undoubtedly helped the home audience to appreciate the

need to keep the nation united—with color and ethnic lines

breached—in the fight against tyranny. In films such as

Bataan (1943) and Guadalcanal Diary (1943), Hollywood pre-

sented a new and progressive image of racial and ethnic har-

mony forged in the crucible of war.

The need for unity in the face of the German and Japan-

ese war machines prompted Hollywood to make an about

face in its usual presentation of the normal American indi-

vidualist hero. A spate of films touted the virtues of working

as a team, teaching the rugged individualist that he had to

give up his solitary ways if the Allies were going to win the

war.

JOHN GARFIELD

, for one, learned that lesson in Air Force

(1943) when his loner character finally pitched in to save the

lives of his buddies.

In true patriotic fashion, war movies made during World

War II proclaimed the necessity and the nobility of sacrifice.

Beginning with John Farrow’s harrowing Wake Island (1942),

a movie that had something of the spirit of the Alamo about

it, martyrdom became a key element in a great many of

World War II’s most emotionally effective movies, such as

The Purple Heart (1944) and They Were Expendable (1945).

Near the end of World War II, when it became apparent

that the Allies would win, a few insightful war movies such

as A Walk in the Sun (1945) and The Story of G.I. Joe (1945)

WAR MOVIES

445

Black Hawk Down, directed by Ridley Scott (2001) (PHOTO COURTESY REVOLUTION STUDIOS)

were made, touching upon the genuine experience of the

common soldier.

It wasn’t until 1946, though, that some of the bitterness

of lost youth and shattered dreams could be played out on the

screen with the release of The Best Years of Our Lives. The film

was a hit and a Best Picture Academy Award winner. For the

most part, however, unlike the antiwar sentiment prevalent in

films after World War I, World War II has traditionally been

presented to movie audiences in a very positive light, even

years later in films such as The Longest Day (1962), A Bridge

Too Far (1977), and The Dirty Dozen (1967).

The difference between the antiwar attitude of most

World War I movies and the prowar attitude of most World

War II films was succinctly summed up in purely Hollywood

terms by Jeanine Basinger in her excellent book, The World

War II Combat Film, when she wrote, “World War I was a

flop and World War II was a hit.”

Although World War II received “A” movie treatment,

the Korean conflict was relegated mostly to “B”s. Director

Samuel Fuller, working on a shoestring, didn’t hesitate to put

his personal stamp on the war in some of the most com-

pelling war movies of the early 1950s, such as The Steel Hel-

met (1950) and Fixed Bayonets (1951).

If Korea was casually overlooked by Hollywood, Vietnam

was consciously avoided by the industry. In the late 1960s and

early 1970s, most filmmakers saw the mass audience as too

politically polarized to make successful movies on the subject.

John Wayne ignored the conventional wisdom and starred in

and directed the pro-Vietnam War film The Green Berets

(1968). It was a poor movie that received awful reviews, but

it was mildly successful at the box office.

Later, as the emotional wounds caused by the Vietnam

War began to heal, a handful of thoughtful movies appeared

in the theaters, among them, Coming Home (1978), which

dealt with the effects of the war on its survivors. Go Tell the

Spartans (1978) became the first movie about that war to

present a realistic and intimate story of soldiers in combat.

The Deer Hunter (1978), a sprawling saga that tried to come

to terms with the American male ethos and its relationship to

the war, stalked away with the Best Picture Academy Award.

The best was yet to come, however, when, the following year,

Francis Coppola’s brilliant psychological examination of the

dark side of the conflict, Apocalypse Now (1979), was released.

After this brief flurry of interest, though, the war wasn’t

graphically presented to film audiences again until 1986 in

the Academy Award-winner Platoon, on the heels of which

came Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987), followed by

BRIAN DE PALMA

’s harrowing Casualties of War (1989), all of

these movies crackling with pent-up rage and disgust for the

waste in human life.

In the meantime, however, America refought the Viet-

nam War in movie fantasies such as Sylvester Stallone’s

Rambo II (1985) and Chuck Norris’s Missing in Action (1984)

and their sequels. If America couldn’t win the Vietnam War

in fact, Stallone and Norris would finally win it in the movies.

With only a few exceptions, the films of the 1990s either

took a self-congratulatory glance back at World War II or

explored more recent military adventures in the Balkans or

in the Persian Gulf. Deterrence (1999) was ahead of its time

in dramatizing a nuclear showdown between the U.S. presi-

dent and Uday Hussein, but the film was released long

before the situation in Iraq became confrontational, and the

film disappeared from sight. Three Kings (1999) was far more

successful, perhaps because of its casting (George Clooney,

Mark Wahlberg, Spike Jonze, and Ice Cube) but mainly

because of its irreverent tone in treating the war in Kuwait

as a black comedy.

A far more serious look at American adventurism in the

Third World was provided by Black Hawk Down (2001), which

took place in Somalia, where American forces attempt to cap-

ture some of a warlord’s top lieutenants. Some American sol-

diers are killed on the mission, and others are wounded. When

the American soldiers return “to leave no man behind,” the

American rescuers are attacked by thousands of Somalis. Nine-

teen Americans and more than 1,000 Somalis died because of

this foolhardy mission. The film, based on an actual incident,

highlighted the limitations of superior American technology in

a Third World setting. Michael Winterbottom’s film, Welcome

to Sarajevo (1997), was also based on a true story by an ITN

reporter covering the turmoil in the Balkans.

The World War II films suggested that, of course, war

was hell, but it had to be approached with a winning attitude.

Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor (2001) was an expensive epic star-

ring Ben Affleck and Josh Hartnett as soldier buddies who

compete for the affection of Kate Beckinsale. Of course,

Pearl Harbor was a military disaster, but the flop film takes a

more positive approach by ending with Jimmy Doolittle’s air

attack over Tokyo.

STEVEN SPIELBERG

’s Saving Private Ryan (1998) was at

first glance a wrenching representation of the Normandy

invasion, as American soldiers were cut down on the con-

tested beaches, but after an initial bloodbath, the film shifted

to a story involving

TOM HANKS

leading a squad of soldiers

on a rescue mission to find and bring back Private Ryan

(Matt Damon), whose three brothers have been killed in

action. The search was undertaken to prevent a repeat of the

real-life Sullivan tragedy, in which all five Sullivan brothers

were killed. The movie suggests that the search was worth it,

but there is a lingering doubt because of the incredible sacri-

fices that had to be made for a single soldier. Still, the film

made more than $190 million.

The Thin Red Line (1998) came out six months after Sav-

ing Private Ryan and concerned the war in the Pacific. Again,

the Americans were successful, but in the aftermath of their

victory, the audience saw the humiliated and humanized

Japanese, and the question arose of whether or not the vic-

tory was worth the sacrifice. Saving Private Ryan swamped

Terrence Malick’s adaptation of the James Jones war novel

because Spielberg concentrated on exterior action, whereas

Malick attempted to probe existentially into his characters,

posing philosophical issues such as “Maybe all men got one

big soul,” as the dialogue attests. The irony was that The Thin

Red Line was based on a novel written by the author of From

Here to Eternity, the iconic 1953 war film.

Bruce Beresford’s Paradise Road (1997), which grossed

only $2 million, was a far more serious treatment of an Aus-

WAR MOVIES

446

tralian story, set during the war in the Pacific. It concerns a

group of women taken as prisoners by the Japanese and

herded into a concentration camp in Sumatra. They are

beaten and humiliated, but their spirit is indomitable, thanks

to the efforts of

GLENN CLOSE

, who organizes them into a

choral group, enabling the physically captured white women

to escape emotionally through their music.

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin (2002) starred

NICOLAS CAGE

as

an Italian soldier more interested in Verdi than military duty.

The main concern of the film is Greek life under the Italian

occupation, which Corelli commands and which ends with a

German massacre of the Italian forces.

ROMAN POLANSKI

’s

The Pianist (2002) told a deeply moving story of a Jewish con-

cert pianist who is trapped in Poland during the German occu-

pation but is able to elude the Nazis and, therefore, escape the

death camps. The film won the Golden Palm at the Cannes

Film Festival and was also honored at the Academy Awards.

The concert pianist of Polanski’s film owes his life to a

music-loving Nazi commandant, who is himself killed when

the Russians sweep across Poland. Quite the reverse happened

in Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993), set in the death

camps in Poland, where a Nazi commandant amuses himself

by shooting Jewish prisoners at random while enjoying Wag-

ner’s music. For this film, Spielberg earned his first Academy

Award for Best Director. The film also won for Best Picture.

See also

ANTIWAR FILMS

;

COPPOLA

,

FRANCIS FORD

;

FULLER

,

SAMUEL

;

KUBRICK

,

STANLEY

;

MILESTONE

,

LEWIS

;

STALLONE

,

SYLVESTER

;

VIDOR

,

KING

;

WAYNE

,

JOHN

.

Warner Bros. The only family-run film company among

the “Big Five” (which included Paramount, MGM, Twentieth

Century–Fox, and RKO). It was founded by the four brothers

Warner, Harry Warner (1881–1958), who was the president

and real power of the firm; Albert Warner (1884–1967), the

least well known of the brothers who handled overseas distri-

bution; Samuel Warner (1888–1927), the visionary brother

who pushed the others toward experimenting with sound but

who died before the talkie revolution began with the Warner

production of The Jazz Singer (1927); and Jack L. Warner

(1892–1978), the most famous of the brothers who oversaw all

production of the Warners’ films at their Burbank studio.

The four Warner brothers were among 14 children born

to a family that emigrated from Poland. The brothers started

out as exhibitors during the first decade of the 20th century.

They then turned to distribution but folded in 1910. They

continued to dabble in the growing movie business, produc-

ing and distributing until they hit it big with their film My

Four Years in Germany (1917). They opened their own

“poverty row” studio in Hollywood and began their 10-year

climb toward success. During those years, they had Ernst

Lubitsch on their staff of directors, but the key to their sur-

vival was twofold. They had a series of hit films starring Rin-

Tin-Tin during the 1920s, plus they also had the brilliant and

driven Darryl F. Zanuck as a writer and later as their chief

producer, reporting to Jack L. Warner until 1933.

The company began to prosper during the booming

1920s, and the studio borrowed heavily, first buying the ail-

ing Vitagraph Company in 1925, thereby gaining studio

space and a distribution system, and later buying theater

chains to ensure exhibition outlets.

In June of 1925, Warner Bros. and Western Electric

began to work together to develop talking motion pictures.

In 1926, Warner established the Vitaphone Company as a

subsidiary for their sound-on-disc shorts, which were mostly

of vaudeville musical arts. The Jazz Singer (1927), the first

feature-length film with songs and a modest number of spo-

ken lines of dialogue, caused a sensation. The Warner film,

starring Al Jolson, became one of the biggest hits of the year,

and the talkies were born.

In the early 1930s, during the Great Depression, the

company was seriously hurt due to its heavy debt burden.

Warner always had a tightfisted reputation, and the studio

responded by making movies faster and more cheaply than

any other major company; it also worked its stars much

harder and paid them far less money than they might have

been paid by Warner competitors, causing clashes, suspen-

sions, and court cases with outspoken stars such as

JAMES

CAGNEY

,

BETTE DAVIS

, and

OLIVIA DE HAVILLAND

.

Among Warner Bros.’ other stars under contract were

GEORGE ARLISS

,

PAUL MUNI

,

EDWARD G

.

ROBINSON

, and

ERROL FLYNN

and, in the 1940s,

HUMPHREY BOGART

and

JOAN CRAWFORD

. The studio also boasted a fine crew of

directors, such as Michael Curtiz and, later,

RAOUL WALSH

and

JOHN HUSTON

.

During the 1930s, the studio was particularly successful

with its cycle of biopics, such as Disraeli (1929), The Story of

Louis Pasteur (1936), and Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet (1940).

These films were excellent entertainment as well as an easy-

to-take education for a large segment of the mass audience.

Just as significantly, Warner captured the public imagina-

tion with its gangster films that began with Little Caesar

(1930) and Public Enemy (1931), as well their spectacular

musicals such as Footlight Parade (1933) and Gold Diggers of

1933 (1933). Most striking were their explosive, socially

conscious films such as I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang

(1932).

More than any other studio, Warner made films in sup-

port of the war effort. The studio released the first anti-Nazi

film, Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939), and even made a pro-

Soviet film, Mission to Moscow (1943), at the request of Presi-

dent Roosevelt. As a studio whose films were predicated on

action, violence, and melodrama, it was also the perfect com-

pany to make patriotic war films that ranged from Action in

the North Atlantic (1943) to Objective Burma! (1945).

The studio’s earlier reputation in hard-boiled gangster

and, later, G-man films during the 1930s, plus its stable of

tough leading men, made Warner a leader in the film noir

genre of the latter 1940s, with classics such as Mildred Pierce

(1945) and White Heat (1949).

The end of the

STUDIO SYSTEM

hit the company hard.

It was forced to sell its theaters in 1951, and profits began

to plummet. Strangely enough, it was television that kept

the company going during the 1950s when Warner TV

shows, such as Cheyenne and Maverick, brought in much-

needed revenue.

WARNER BROS.

447