Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

1930s and the first half of the 1940s, doing most of their best

work during that period. The Stooges were nominated for an

Oscar for Men in Black (1934) but were beaten by Disney’s

Three Little Pigs—only to come back the following year with

Three Little Pigskins (1935). Among their other classic shorts

were Hoi Polloi (1935), Violent Is the Word for Curly (1938),

Calling All Curs (1939), and You Natzy Spy (1940), in which

Moe bore an amazing resemblance to Hitler.

After Curly suffered a stroke in 1946, the call went out to

brother Shemp to return to the team. He did so with modest

results, but the group was never the same without Curly.

When Shemp died in 1955, Joe Besser filled in for two years

and was then replaced by Joe DeRita, who shaved his head and

called himself Curly-Joe. The team went steadily downhill.

The Stooges had never been big money-makers for

Columbia, but they were kept on because Harry Cohn report-

edly thought of them as his good luck charms; they had come

to the studio in the year that Columbia hit the big time with

FRANK CAPRA

’s It Happened One Night (1934), and the movie

mogul was content to keep them around. When Cohn died in

1958, the Three Stooges lost their patron, and they were let

go after completing their last short, Sappy Bullfighters (1958).

But a curious thing happened. Columbia unloaded all of

the Three Stooges shorts featuring Curly to television, and a

whole new audience of kids discovered the trio and went crazy

for them. In the twilight of their lives, the Three Stooges were

hotter than they had ever been in their entire careers. Their

faces appeared on lunch boxes, and they cashed in with per-

sonal appearances and a series of terrible feature films, among

them Have Rocket, Will Travel (1958), The Three Stooges in

Orbit (1960), and The Three Stooges Meet Hercules (1961).

Without Curly or Shemp, and feeling their age, Moe and

Larry, with the none-too-talented Curly-Joe, continued to

lumber through featured appearances in movies such as Four

for Texas (1963), but they finally wore out. Larry Fine’s stroke

in 1971 effectively shut down the act. Moe died not long after

the death of his dear friend and partner Larry in 1975.

See also

COMEDY TEAMS

.

Tierney, Gene (1920–1991) One of Hollywood’s great

beauties, she had an elegant yet sexy manner on screen that

suggested a blue flame: cool to the eye but hot to the touch.

She appeared in 36 films, starring in most of them and mak-

ing her best during the mid- to late 1940s. The one film for

which she is best remembered is Laura (1944), in which she

played the title role.

Tierney was the daughter of a well-to-do Wall Street

trader who, when she decided to become an actress, fully

supported her and even formed a corporation called Belle-

Tier that was designed solely to push her career. By 1939

Tierney was on Broadway, and when she appeared on stage

in The Male Animal the next year,

DARRYL F

.

ZANUCK

was in

the audience. He saw her screen potential and signed her to

a contract. That same year she made her movie debut in The

Return of Frank James (1940).

Tierney was given the star treatment very early on. She

played Ellie May in Tobacco Road (1941), she was Belle in Belle

Star (1941), and she was the female lead in

ERNST LUBITSCH

’s

Heaven Can Wait (1943), but it was Laura that hurled her into

the Hollywood firmament of stars. In this romantic suspense

movie directed by

OTTO PREMINGER

, a detective (played by

Dana Andrews) falls in love with a portrait of Laura (Tierney),

thinking that the beautiful woman in the picture has been

murdered. When she suddenly appears, alive and well, the

two are drawn together while a thwarted murderer (Clifton

Webb) continues his efforts to kill her.

The movie was a smash hit and has since become a clas-

sic. Tierney has been so associated with Laura that one tends

to forget that she garnered an Oscar nomination for Leave

Her to Heaven (1945), gave an achingly tender performance in

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947), and was excellent in

Whirlpool (1949). Most of her other films in the late 1940s

and early 1950s were ordinary, unmemorable entries such as

The Iron Curtain (1948), Night and the City (1950), The Mat-

ing Season (1951), and Plymouth Adventure (1952).

Tierney’s personal life was far more dramatic than many

of her later movies. She had dated John F. Kennedy before he

entered politics, married fashion designer Oleg Cassini in

1941, and, after their divorce in 1952, became deeply

involved with Aly Khan, the ex-husband of

RITA HAYWORTH

.

When that affair ended, she went into a severe emotional

TIERNEY, GENE

428

Gene Tierney, in her most famous role, is seen here as

Dana Andrews first saw her in Laura (1944). Andrews falls

in love with her image even though he believes Tierney’s

character is dead.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF GENE

TIERNEY LEE)

tailspin, spending 18 months in a sanitarium. Later, in 1960,

she married an ex-husband of

HEDY LAMARR

and settled in

Texas. After remarrying, she made a few appearances in

movies such as Advise and Consent (1962) and Toys in the Attic

(1963). One can glimpse her final appearance on film in The

Pleasure Seekers (1964).

Tiomkin, Dimitri (1899–1979) One of the great com-

posers for the screen whose scores were often notable for their

evocative combination of well-known classics and his own

original music. Tiomkin’s scores reached out to audiences; one

was often aware of his music in the films he scored but was not

distracted by it. Versatile and imaginative, Tiomkin, a pioneer

among Hollywood composers, was honored with four Oscars

for his efforts in a film career that lasted more than 40 years.

Born in Russia, Tiomkin received his early musical train-

ing at the St. Petersburg Conservatory of Music. He was con-

sidered a brilliant young man, making his living in the 1920s

as a concert pianist and conductor. Long before he came to

the United States, Tiomkin was intrigued with American

music; he was the first concert artist to play George Gersh-

win’s music in Europe.

The composer arrived in the United States in 1925 and

never left, becoming a citizen in 1937. Not long after coming

to America, Tiomkin settled into his new craft of writing film

scores for movies. He wrote ballet music for Devil-May-Care

(1929) and several other early sound films, eventually win-

ning the opportunity to write the music for all sorts of films

from horror movies such as Mad Love (1935) to adventures

such as Spawn of the North (1938).

Tiomkin worked closely with several directors throughout

their careers: He wrote the scores for many of

FRANK CAPRA

’s

movies, including Lost Horizon (1937), You Can’t Take It with

Yo u (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Meet John

Doe (1941), and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946); he was just as com-

patible with a director as diametrically different in tone and

style as

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

, for whom Tiomkin wrote the

music for, among others, Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Strangers

on a Train (1951), and Dial M For Murder (1954). Tiomkin

also wrote scores for a great many of

HOWARD HAWKS

’s

adventure films such as Only Angels Have Wings (1939), Red

River (1948), The Big Sky (1952), and Rio Bravo (1959).

The last three films mentioned above are particularly

notable because they were westerns. In the 1950s, Tiomkin

became the leading composer of scores for oaters when he

wrote the music and the theme song for High Noon (1952),

winning Academy Awards for both. He did not, however,

stick to westerns; his interests were far too wide ranging. He

also wrote the music for The High and the Mighty (1954), win-

ning yet another Oscar, and The Old Man and Sea (1958), for

which he won his fourth and final Academy Award.

Tiomkin continued working throughout the 1960s, only

slowing down near the end of the decade. His theme song for

Town Without Pity (1961) became a hit, but his final achieve-

ment was his version of Tschaikovsky, which he produced,

directed, and orchestrated in a joint American and Russian

production in 1970.

Toland, Gregg (1904–1948) A legendary cinematog-

rapher whose work during the 1930s and early 1940s set a

standard that has never been surpassed. Given a great deal of

freedom by producer

SAMUEL GOLDWYN

, for whom he usu-

ally worked, Toland adventurously lit movies to stunning

effect and devised camera angles and set-ups that dramati-

cally affected and enhanced a great many films.

Toland started his career in the silent era as an assistant

cameraman at the age of 16. He learned his craft during the

next 10 years and began to work as a lighting cameraman in

1929, coshooting more than a half-dozen films before taking

over as sole cameraman in 1931 for Palmy Days. He shot a

number of popular comedies, such as The Kid from Spain

(1932), and his talent led Samuel Goldwyn to give Toland

virtual carte blanche in photographing his newly imported

star, Anna Sten, with the hope of turning her into a glam-

orous beauty to match Garbo and Dietrich. Toland didn’t let

Goldwyn down. Nana (1934), We Live Again (1934), and The

Wedding Night (1935) were visually stunning movies. Film

historian George Mitchell referred to Toland’s efforts for We

Live Again as “some of the most breathtaking photography

ever recorded by a motion picture camera.” If Anna Sten did-

n’t become a star, it was not for Toland’s lack of skill.

With his reputation as a leading cameraman made in the

mid-1930s, he was assigned to bigger and better films in

which to display his craft. His rich and evocative lighting can

be seen in films such as The Road to Glory (1936), History Is

Made at Night (1937), and one of his most beautifully pho-

tographed films, The Grapes of Wrath (1940).

As Leonard Maltin explained in his excellent book,

Behind the Camera, Toland had a long and fruitful association

with

WILLIAM WYLER

, shooting many of the director’s best

films, including These Three (1936), Dead End (1937), Wuther-

ing Heights (1939), for which the cinematographer won an

Oscar, The Westerner (1940), The Little Foxes (1941), and The

Best Years of Our Lives (1946).

ORSON WELLES

deserves the credit for

CITIZEN KANE

(1941), but the neophyte director could not have realized the

film without Toland’s help. It was in Kane that Toland per-

fected the

DEEP FOCUS

photography that film students still

study today. He also shot ceilings in that movie for the first

time, and his ominous lighting helped launch the film noir

style that would soon follow.

During World War II, Toland photographed and codi-

rected (with

JOHN FORD

) December 7th, a documentary film

that brought him a second Oscar. But after his work on The

Best Years of Our Lives, the cinematographer made just three

more films before his sudden death from a heart attack at the

age of 44. His last film, Enchantment (1949), was released the

year after his death.

Tracy, Spencer (1900–1967) He is considered by

many of his colleagues and film historians to be the finest

American film actor of his time. With his craggy face, burly

build, and soulful eyes, Tracy held the screen with such a nat-

ural grace that he hardly seemed to be acting. Originally

typed as a gangster, the actor soon blossomed into a versatile

TRACY, SPENCER

429

character actor and star and then held top billing until his

death. Most film fans remember him as a member of one of

Hollywood’s most-loved screen teams, with Katharine Hep-

burn, in a total of nine movies. Less well known is the fact

that Tracy holds the record for the most Best Actor Academy

Award nominations—nine (he won the Oscar twice). He did-

n’t let such acclaim go to his head; this honored star’s pre-

scription for acting was merely, “Just know your lines and

don’t bump into the furniture.”

Born in Wisconsin to a middle-class family. Tracy found

he had a talent for speaking in public while a member of the

Ripon College debating team. Drawn to the stage, he trav-

eled to New York to become a student at the American Acad-

emy of Dramatic Arts. He fared well in New York, landing an

important role in the Broadway production of A Royal Fan-

dango in 1923. He worked steadily throughout the 1920s

until he had a smash hit playing a murderer on death row in

the Broadway production of The Last Mile in 1929. His suc-

cess led to screen tests in a Hollywood that was hungry for

stage stars who could excel in the new talkie era, but the ver-

dict from such studios as MGM, Fox, and

WARNER BROS

. was

that Tracy had no future in the movies. Fortunately, director

JOHN FORD

had seen Tracy in The Last Mile and knew talent

when he saw it. He talked Fox into giving Tracy a contract,

and the actor was given the lead in his first feature-length

movie, Ford’s prison picture Up the River (1930).

More prison and gangster movies followed, such as

Quick Millions (1931), Disorderly Conduct (1932), and 20,000

Years in Sing Sing (1933). His reputation as an actor was

already growing, and the latter film helped establish him as

a genuine star, but he broke out of the hardboiled tough guy

roles for good when he gave an electric performance in The

Power and the Glory (1933). His range of roles then

increased dramatically to include comedies, romances, and

period pieces.

During the mid-1930s, however, Tracy’s irascibility and

public drinking became a serious problem. Twentieth Cen-

tury–Fox tried to discipline him by giving him lesser roles,

but that merely put them at loggerheads with the actor.

Finally, he managed to get himself fired, but not until he had

made a fascinating version of Dante’s Inferno (1935).

MGM, concerned with Tracy’s bad-boy reputation and

worried, as well, that he lacked sex appeal, nevertheless took

a gamble and signed him up. The deal paid off handsomely.

The actor became one of the studio’s biggest stars in critical

and/or commercial hits, such as the antilynching movie Fury

(1936), San Francisco (1936), a Best Picture nominee for the

year (and Tracy’s first Best Actor–nominated performance),

Libeled Lady (1936), and Captains Courageous (1937), for which

he won his first Academy Award for Best Actor.

Although not every movie he made was a winner, Tracy

scored often enough to approach “The King,”

CLARK GABLE

,

in popularity, and by 1940, after making such films as Boy’s

Town (1938) for which he was honored with his second Oscar,

Stanley and Livingstone (1939), and Boom Town (1940), Tracy

finally outperformed Gable and entered his most successful

decade as an actor. It was also the decade in which he first

met and began to work with Katharine Hepburn.

The two were first teamed in Woman of the Year (1942).

The movie was so well received—and the two stars seemed so

natural together—that they were brought together again in

Keeper of the Flame (1943). Later, they were teamed again in

Without Love (1945), and it began to seem as if Tracy and

Hepburn were inseparable—at least on screen. Their roman-

tic relationship behind the scenes was handled discreetly due

to Tracy’s marriage (both he and his wife were Catholics and

would not divorce). For years, the two stars continued to

appear together in films such as State of the Union (1948),

Adam’s Rib (1949), Pat and Mike (1952), Desk Set (1957), and

his last film, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967). In all of his

films—even those with Hepburn—he insisted on top billing.

In addition to his collaborations with Hepburn, Tracy

made one of World War II’s most effective anti-Nazi films,

FRED ZINNEMANN

’s The Seventh Cross (1944). He also eased

into strong father roles in movies such as the hit comedy

Father of the Bride (1950), for which he received yet another

Oscar nomination, its sequel, Father’s Little Dividend (1951),

and The Actress (1953).

Tracy’s drinking and bad temper began to get the better

of him in the 1950s, and his output dropped precipitously.

Nonetheless, he won Oscar nominations for his perform-

ances in Bad Day at Black Rock (1955) and The Old Man and

the Sea (1958). Many believed that he should have been nom-

inated for The Last Hurrah (1958), which was one of his last

truly great performances.

Ill health began to slow Tracy down further. Before his

health failed him completely, however, he managed to give

crackling good performances in four more films, garnering a

staggering three more Oscar nominations. Tracy and Fredric

March gave acting lessons in Inherit the Wind (1960), each of

them chewing up the scenery. He was sober and strong as the

judge in Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) but sadly seemed tired

though game in It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), his

only nonnominated performance of the decade. Finally, after

a long absence from the screen, he allowed himself to be

coaxed into (and through) Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner by

Hepburn and director

STANLEY KRAMER

. He received his

ninth and final Oscar nomination for his role in the film. He

died shortly after filming was completed.

See also

HEPBURN

,

KATHARINE

;

SCREEN TEAMS

.

trailer More popularly known as “coming attractions,”

trailers are short films usually of less than 90 seconds’ dura-

tion that extol the virtues of movies either soon to be

released or playing at another theater. Trailers are gener-

ally—but not always—put together from the most intrigu-

ing, most action-filled, scenes of a movie. It is, therefore, not

surprising that many movie trailers are more exciting than

the movies themselves.

Ironically, trailer is a misnomer because these short com-

mercials precede feature films rather than trail them. Though

the derivation of the name is unknown, one theory has it that

the advertisement was traditionally shown after the first film

of a double feature (or, rather, at the beginning of the second

film), hence the name trailer.

TRAILER

430

Travolta, John (1954– ) An actor-singer-dancer who

achieved movie stardom in the late 1970s. Handsome and

charming in a boyish and cocky manner, Travolta promised

to become a major superstar until his career stalled after a

string of critical and box-office duds in the mid-1980s. Still

working, however, Travolta has made an effort to grow as an

actor, and a more mature major star emerged.

The youngest of six children, Travolta grew up in New

Jersey, studying acting with his mother. He left school at 16

to pursue a career in the theater, working in stock, TV com-

mercials, and eventually Broadway in Grease (though not an

original cast member).

Travolta’s first film appearance was in The Devil’s Rain

(1975), but he became a surprise TV star that same year when

he played the role of Vinnie Barbarino in the hit sitcom Wel -

come Back, Kotter. He showed his range in the TV movie The

Boy in the Plastic Bubble (1975) and indicated genuine big-

screen promise in a supporting role in

BRIAN DE PALMA

’s

smash hit Carrie (1976). Producer Robert Stigwood signed

the young actor to a three-picture contract, the first of which

was Saturday Night Fever (1977), the film that made Travolta

an instant movie star and launched a disco craze. His acting

in the film, and particularly his dancing, helped earn Travolta

an Oscar nomination as Best Actor.

His next film, Grease (1978), was an equally huge hit, and

the actor’s reputation as a talented musical performer was

firmly established. Moment by Moment (1978), in which he

costarred with Lily Tomlin, was a major bomb. He recouped,

however, with Urban Cowboy (1980), a film that spawned a

resurgence in all things country/western.

His films since Urban Cowboy have been lackluster, some

of them popular with critics and others popular with fans but

none of them popular with both. For instance, he starred in

Brian De Palma’s Blow Out (1981), a loser at the box office

but generally admired by the media. Conversely, his reprise

of the role of Tony Manero (from Saturday Night Fever) in

Staying Alive (1983), a film directed by

SYLVESTER STAL

-

LONE

, brought in ticket buyers by the truckload but was

roundly panned by critics. Perfect (1985) was anything but;

critics booed and fans stayed away.

Critics admired his courage for tackling a difficult role in

ROBERT ALTMAN

’s TV adaptation of Harold Pinter’s The

Dumb Waiter (1987), and as the 1980s came to a close, Tra-

volta seemed to be entering a new phase of his career with the

comedy Look Who’s Talking (1989), which was followed by

Look Who’s Talking, Too (1990) and Look Who’s Talking Now

(1993).

QUENTIN TARANTINO

’s Pulp Fiction (1995) gave him

a new lease on his career. Playing a hit man opposite partner

SAMUEL L

.

JACKSON

, Travolta received Oscar and Golden

Globe nominations. The following year, he received another

Golden Globe nomination for his role as a loan shark and

film buff in Get Shorty. In 1996 he was an archangel hoofer in

Michael, but he had a darker side in some of his 1990s films:

In Broken Arrow (1995) he played a psychotic villain, and in

Face/Off, he was the villain to

NICOLAS CAGE

’s good guy. The

New Jerseyite went south in Primary Colors (1998), playing a

southern governor who seeks the presidential nomination;

the political chicanery and the sexual exploits in the film were

inspired by President Bill Clinton’s life. One of his best roles

was as a sleazy, opportunistic lawyer who turns out to have a

heart of gold, in A Civil Action (1998), but

ROBERT DUVALL

,

who played his courtroom opponent, got the acting nomina-

tions. Travolta also appeared in some military movies: The

Thin Red Line (1998), The General’s Daughter (1995), and the

awful Battlefield Earth (2000). Like

JON VOIGHT

, in his later

years Travolta seems to have acquired a talent for playing vil-

lains, and he has made a few bad decisions. Although Travolta

has not garnered many awards, he has demonstrated his box-

office appeal. His films have grossed almost $2 billion, and

his average gross per film is more than $50 million.

treatment The second stage in the development of a con-

cept into a script. After the original idea for a film has been

presented—often on one single sheet of paper—a treatment

is ordered, which fleshes out the concept into something

approaching narrative form, detailing all the major scenes

and often including snatches of dialogue to suggest the tone

of the story. The treatment is a step short of a script.

Trevor, Claire (1909–2000) An actress who excelled

in playing women of easy virtue in a film career spanning

more than 30 years. During her busiest years in Hollywood,

the 1930s and 1940s, Trevor could be found mostly in con-

temporary dramas as a “bad girl” (a Hollywood euphemism

for a prostitute), in westerns as a “saloon girl” (another

euphemism), a gangster’s moll, or any other sort of loose,

down-on-her-luck character. She was nominated three times

for Best Supporting Actress

ACADEMY AWARDS

in such roles,

winning the Oscar once. For the most part, however, this tal-

ented actress worked in lower-budget movies that received

little attention. At one time, she was known in the industry as

Queen of the B’s.

Born Claire Wemlinger to a comfortable family, she stud-

ied art at Columbia University and then took up the theater

at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. After a modest

amount of stage experience, she was signed by Fox to a five-

year contract, making her movie debut in a western called

Life in the Raw (1933). She quickly moved up to lead roles,

but she stayed mostly in “B” movies during her early years,

with the fascinating exception of Dante’s Inferno (1935) and To

Mary with Love (1936). By this time, however, she had already

become typecast in tawdry tough-girl roles, making her a

natural for her first genuinely important part as

HUMPHREY

BOGART

’s former girlfriend turned whore in the heralded

screen version of

DEAD END

(1937). Their scene together in

an alley was devastatingly honest and powerful and remains

the highlight of the film more than 50 years after its release.

Her performance brought Trevor her first Oscar nomination,

but, unfortunately, she wasn’t free of the “B”s.

It wasn’t until 1939 that she was able to sink her teeth

into a significant part in a well-scripted movie. The film was

JOHN FORD

’s

STAGECOACH

, in which she played a woman of

questionable virtue. Not a surprise. But no one played such

parts better than Trevor, and the film’s success gave her the

TREVOR, CLAIRE

431

opportunity to appear in films better than those she was accus-

tomed to, such as The Dark Command (1940), Honky Tonk

(1941), Texas (1941), and The Adventures of Martin Eden (1942).

It didn’t last. During the rest of the 1940s and 1950s, her

career began a slow but inexorable downward slide, punctu-

ated by a handful of good movies. Among her better films

were Murder, My Sweet (1944) with

DICK POWELL

as Philip

Marlowe, and Key Largo (1947), in which she probably gave

the greatest performance of her career, earning a Best Sup-

porting Actress Oscar for her portrayal of the alcoholic girl-

friend of gangster Johnny Rocco (

EDWARD G

.

ROBINSON

).

Seven years later came another solid vehicle, The High and the

Mighty (1954), and Trevor was nominated for her third Acad-

emy Award.

She worked less often and in increasingly smaller parts

during the rest of the 1950s and 1960s, but at least the

movies she appeared in were generally better. Man Without

a Star (1955), Marjorie Morningstar (1958), Two Weeks in

Another Town (1962), and The Stripper (1963) offered Trevor

some of her best roles as her career neared its end. When

not acting in films, she put her talents to work in television,

winning an Emmy for her 1956 performance in the TV

broadcast of Dodsworth.

Trevor’s last motion picture performance was in a minor

movie called The Cape Town Affair (1967).

Turner, Kathleen (1955– ) An exotic blonde actress

who became a major film star of the 1980s. In addition to her

good looks, her most compelling feature is her voice, which

she claims is distinctly her own creation. The accent is a lit-

tle British, a little Spanish, and a little otherwordly, which

made her the perfect choice for the off-screen voice (uncred-

ited) of the animated bombshell Jessica Rabbit in Who

Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988).

Turner’s father was a career foreign-service officer who

held jobs all over the world, taking his family with him on his

travels. While a teenager in England, she decided to become

an actress. After her father died and her family moved to Mis-

souri, she continued studying theater and eventually made her

initial breakthrough on a daytime soap opera, The Doctors.

Turner honed her skills and gained valuable experience

during her 20 months doing daytime drama, and it paid off

when she was cast as the female lead in Lawrence Kasdan’s

Body Heat (1981). It marked not only Turner’s debut in

motion pictures but also Kasdan’s, and it was costar William

Hurt’s second movie. Despite the relative inexperience of the

writer-director and his two actors, the film was a surprise hit,

and Turner was immediately touted as a future star, thanks to

her sultry, sophisticated performance.

She went on to choose an eclectic mix of films during the

balance of the 1980s, including the

STEVE MARTIN

comedy

romp, The Man With Two Brains (1983), and the intense,

steamy Ken Russell indulgence, Crimes of Passion (1984).

Then, in short order, she suddenly fulfilled the prophecies of

the critics, scoring along with

MICHAEL DOUGLAS

in the

$100-million-grossing Romancing the Stone (1984), followed

by the disappointing but still commercially successful sequel,

Jewel of the Nile (1985). Turner played opposite Douglas yet

again in the black comedy War of the Roses (1989). She gave

strong performances during the mid- to late 1980s in such

critical and box-office standouts as Prizzi’s Honor (1985),

Peggy Sue Got Married (1986), and The Accidental Tourist

(1988), the latter film reuniting the Body Heat team in an

entirely different (and more sedate) movie.

Though she was in a couple of commercial flops, such as

Switching Channels (1988), Turner’s career was among the most

varied and most successful of any actress during the 1980s.

In 1989, Turner costarred with Michael Douglas in The

War of the Roses, an acerbic black comedy about divorce in

America. In 1991, she played gumshoe V. I. Warshawski in

an unsuccessful neo-noir thriller. Undercover Blues (1993)

was a comedy thriller about married spies (Turner and Den-

nis Quaid) trying to stop an old adversary from selling

stolen weapons. But mostly matronly roles awaited her dur-

ing the 1990s.

In 1993, for example, she played the mother who is try-

ing to pull her daughter out of a fantasy world in House of

Cards and was convincingly sympathetic. Perhaps her best

role of the 1990s, however, was in John Waters’s Serial Mom

(1994), a dark comedy about a suburban housewife who mur-

ders people who upset her view of the world. On trial for

multiple murders, she is acquitted after she befuddles one

witness by flashing him. Thereafter, she stalks a young

woman who didn’t know better than to wear white shoes after

Labor Day, following her into the ladies’ room to dispatch

her for her transgression.

Since then, Turner has appeared in Moonlight and

Valentino (1995) as an overbearing ex-stepmother of Eliza-

beth Perkins. She played the fairy godmother in A Simple

Wish (1997). In 1999, she appeared in Baby Geniuses, but,

more significantly, she played the uptight, dominating, overly

religious mother of the beautiful Lux sisters in The Virgin

Suicides. The latter was a great performance in a relatively

marginal independent film, adapted from the novel by Jeffrey

Eugenides and directed by Sofia Coppola, the daughter of

Francis Ford Coppola. Unfortunately, not all of the roles

offered to Turner were of that caliber.

Turner, Lana (1920–1995) An actress initially more

famous for her physique than her acting, yet who had suffi-

cient star power to fuel a film career lasting more than 40

years. A symbiosis existed between Turner and her fans; her

personal tribulations, which were trumpeted in the press,

made her a surprisingly sympathetic figure, and audiences

forgave her mediocre performances as long as they could

adore her on screen. Though Turner appeared in a range of

movies, she was best in melodramas, playing lower-class

women who fought their way to wealth and power.

Born Julia Jean Mildred Frances Turner, her childhood

was not as elegant as her name. Her father was murdered in

a robbery attempt when she was nine years old, sending her

family into a financial tailspin. She spent some time in foster

homes before finally reuniting with her mother, who had

moved to Los Angeles to make a living as a beautician.

TURNER, KATHLEEN

432

Legend has it that Turner was discovered sipping a soda

in Schwab’s Drugstore, but legend is wrong. She was actually

at Currie’s Ice Cream Parlor, which happened to be across

the street from Hollywood High School, which Turner

attended. She was 15 years old when Billy Wilkerson of The

Hollywood Reporter spotted her and helped her break into the

movies at

WARNER BROS

.

Turner made her debut in They Won’t Forget (1938), in

which she can be seen sipping a soda at a drugstore counter,

which later undoubtedly helped foster the legend of her dis-

covery. In any event, she was not rushed to stardom—at least

not yet. Mervyn Le Roy had directed They Won’t Forget, and

he thought she had “something”; Warner Bros. was not con-

vinced. When Le Roy went to MGM in 1938, he asked if he

could take Turner with him. The studio let her go.

At MGM, Turner was groomed, as were many stars, in

featured roles in their many successful series. She appeared in,

among others, Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938) and Calling Dr.

Kildare (1939). Her initial success, however, did not come

from the movies but from MGM’s campaign to prominently

feature her full figure in tight pullovers in a number of pin-up

pictures, billing her as “The Sweater Girl.” As a result of her

new image, Turner was soon rushed into sexy melodramas

such as Honky Tonk (1941), Somewhere I’ll Find You (1942), and

Johnny Eager (1942), becoming an instant sensation.

Turner’s appeal didn’t diminish one iota after the war

when she starred in the then steamy version of The Postman

Always Rings Twice (1946), a film that is generally credited as

her best. Other popular films followed, including Green Dol-

phin Street (1947) and Cass Timberlane (1947), but in the late

1940s and early 1950s Turner began to lose her appeal. Dur-

ing the first half of the 1950s, none of her films did well

except for The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), in which she was

cleverly cast as a bad actress.

By the late 1950s, having been in one flop after another,

it seemed as if Turner was washed up—until an ironic com-

bination of events briefly reestablished her as a major

celebrity. Her daughter killed her longtime boyfriend, a

gangster named Johnny Stompanato, knifing him to death in

Turner’s home. The tabloids went wild, especially when love

letters between Turner and the gangster were read in court as

evidence. Eventually, Turner’s daughter was acquitted on the

grounds of justifiable homicide (she had claimed she was pro-

tecting her mother). Even as the scandal unfolded, Turner’s

latest film, Peyton Place (1957), was released. The sexy soap

opera, buoyed by the publicity Turner received, became a

blockbuster hit, and in a classic Hollywood twist, Turner was

nominated for a Best Actress Oscar for her performance in

the film, the only acting accolade she ever received.

Her last big success was the highly regarded

DOUGLAS

SIRK

sudser Imitation of Life (1959). She continued to work in

films throughout the 1960s but with little impact. Her best

known movie in this period of decline was Madame X (1965).

By 1969 she was ready to try TV, starring in the short-lived

series The Survivors. There were a smattering of film appear-

ances in unimportant movies during the 1970s and then a

stint on the prime-time TV soap Falcon Crest in 1982, fol-

lowed by semiretirement.

She has married eight times (she married the same man

twice), and Turner’s personal life would make a better movie

than most of those in which she starred. Among her many

husbands were bandleader Artie Shaw and one-time movie

Tarzan Lex Barker. She was also reportedly involved at one

time with multibillionaire

HOWARD HUGHES

.

See also

SCANDALS

.

Twentieth Century–Fox One of Hollywood’s “Big Five”

film companies. It was formed in 1935 as a result of a merger

between an established studio fallen on hard times, the Fox

Film Corp., and a new studio, Twentieth Century. The ori-

gins of the Fox Film Corp. go back to nickelodeon days when

entrepreneur William Fox formed the Greater New York

Film Rental Company to distribute motion pictures. In 1915,

he moved the New York operation to Los Angeles and

changed the name to the Fox Film Corp. By the late 1920s,

after a prodigious campaign to acquire theaters and feature

directors and stars such as

JOHN FORD

, Raoul Walsh, Tom

Mix, and Janet Gaynor, and after experimenting with syn-

chronized sound (utilizing the sound-on-film process called

Movietone), Fox ran afoul of government antitrust actions.

Fox was forced out of the company in 1930.

Meanwhile,

DARRYL F

.

ZANUCK

, a successful production

chief at Warner Bros., was growing dissatisfied with his rela-

tionship with Jack Warner. He resigned in 1933 and with for-

mer United Artists executive

JOSEPH SCHENCK

, formed

Twentieth Century Pictures (the name supposedly came from

an executive who assured Zanuck that the name would be

good for at least 67 years!). Its first release was The Bowery

(1933), directed by Raoul Walsh. The next two years saw

such releases as The Affairs of Cellini (1934), The House of

Rothschild (1935), and Les Miserables (1935). After the merger

with Fox in 1935, Zanuck assumed complete control.

For the next 20 years, a diverse roster of stars, filmmak-

ers, and pictures were developed. Little

SHIRLEY TEMPLE

,

the most famous child star of her day, virtually kept the stu-

dio afloat in the 1935–39 period, with hits like Captain Janu-

ary (1936) and Wee Willie Winkie (1937). Director John Ford

was in his prime, scoring with Drums Along the Mohawk

(1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940) Young Mr. Lincoln (1940),

and others. Some of the greatest Technicolor musicals from

the 1940s exploited the so-called “Fox Blondes”—

BETTY

GRABLE

, June Haver, and Alice Faye (Marilyn Monroe came

along in the 1950s). The most important series of social-con-

sciousness films, aside from Warner Bros., emerged in the

1940s with Wilson (1943), Gentlemen’s Agreement (1947), and

The Snake Pit (1947).

In 1953, Spyros Skouras, then president of the company,

introduced a wide-screen, anamorphic process called Cine-

maScope with The Robe. It was his intention to produce all

future Fox releases in color and CinemaScope. However, the

process was subsequently rivaled by other wide-screen

processes such as Todd-AO and VistaVision. In 1956, Zanuck

left the company but, after the debacle of Cleopatra (1961),

returned as chairman of the board with his son, Richard, as

production chief in Hollywood. Also in 1956, a substantial

TWENTIETH CENTURY–FOX

433

package of theatrical features was sold to National Telefilm

Associates (NTA). Although some smash successes followed—

The Sound of Music (1965) and the first Star Wars film in 1977,

in particular—both Zanucks were eventually forced out.

Since 1985, Australian magnate Rupert Murdoch (News

Corp.) has been the studio’s owner. At the outset, Murdoch’s

ambition was to create Fox Broadcasting, a fourth U.S. tele-

vision network. Ironically, in 1989 the studio’s moviemaking

division assumed the name of William Fox’s original silent-

era studio, the Fox Film Corp.

Twentieth Century Fox movie studios, based in Los Ange-

les, is now a subsidiary of Fox Entertainment Group, Inc.

Other companies included in Fox Group are Fox Broadcast-

ing, Fox Kids, and Fox Sports. Fox also owns Fox Searchlight

and Fox 2000 Pictures, both independent and lower-budget

film distributors. Twentieth Century Fox films are some of the

highest-grossing in history and help Fox to keep its place in

the competitive world of Hollywood. Fox’s recent hits include

Titanic (1997), which it distributed in cooperation with Para-

mount, Independence Day (1996), and the extremely popular

Aliens, Die Hard, and Star Wars films.

The company is a good example of vertical integration.

While its production branch, which includes the studios, film

and television libraries, and other production facilities, pro-

vides content that meet the highest standards in the industry,

the distribution and exhibition outlets of the corporation

provide a robust platform to launch the programs in quest of

an audience (News Corp., Fox Entertainment Group).

Among Twentieth Century Fox’s recent releases are Moulin

Rouge (2001), Planet of the Apes (2001), Minority Report (2002),

One Hour Photo (2002), Runaway Jury (2003), and Master and

Commander (2003).

TWENTIETH CENTURY–FOX

434

Ulmer, Edgar G. (1904–1972) A director forced to

work with an inordinate number of ridiculous scripts who,

nonetheless, proved that a fluid camera and a foreboding

visual style could make an artistic statement of even the worst

vehicles Hollywood could offer. Ulmer not only suffered

with poor scripts; he also had to make do with threadbare

budgets. Nonetheless, he contributed a surprising number of

minor screen classics, including The Black Cat (1934), Blue-

beard (1944), Detour (1946), and Ruthless (1948).

Ulmer’s career began in Austria, though he received his

most important training in Germany under the tutelage of

such greats as the stage’s Max Reinhardt and the movies’ F.

W. Murnau. When Ulmer finally became a director in Hol-

lywood in 1933, he made a handful of films, including the

highly regarded horror film The Black Cat, before spending

the rest of the decade making movies in everything from

Ukrainian to Yiddish.

In the early 1940s, he worked his way back to Hollywood,

and it was during the next 10 years that he made the major-

ity of his best films. His German Expressionist style was well

suited to the developing

FILM NOIR

movement of the latter

1940s and early 1950s, and even cheap little movies such as

Murder Is My Beat (1952) with stars as dubious as Paul Lang-

ton and Barbara Payton made audiences take notice of a dis-

tinctive talent at work.

Ulmer’s films might have been thoroughly forgotten had

not the influential French film critics of the 1950s discov-

ered him as a true

AUTEUR

. During the 1960s, his cause was

taken up in America by the likes of critic Andrew Sarris and,

today, thanks to their efforts, Ulmer is considered a notable

minor artist.

United Artists One of Hollywood’s “Little Three”

motion picture companies (along with Columbia and Uni-

versal). Founded in 1919 by four of the greatest names in the

movies—

MARY PICKFORD

,

DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS

,

CHARLIE

CHAPLIN

, and

D

.

W

.

GRIFFITH

—United Artists claimed to

be the first company in which motion picture performers

acquired complete autonomy over their work and released

each picture singly, on its own merits, free of the “closed

booking” procedures that had reigned since the mid-teens.

However, there had been several efforts previous to UA that

attempted a system of “open booking”: In 1915, Lewis

Selznick rented the pictures of Clara Kimball Young singly

with his Clara Kimball Young Pictures Company; in 1919,

William Hodkinson attempted an “open market” policy with

his own distributing organization. Now, as heads of their

own respective production companies, Pickford, Chaplin,

Fairbanks, and Griffith controlled all artistic, financial, and

promotional activities.

The four partners first had to break free of their respec-

tive obligations to other studios. Pickford, Chaplin, and Grif-

fith all owed several pictures apiece to First National, and

Fairbanks was under contract to Paramount until May 1919.

The burden of the first releases would fall to Fairbanks,

whose thrill comedies, His Majesty the American and When the

Clouds Roll By, were both released in 1919. Some of the best-

known work of each founder came from the first decade of

the studio: After 1920 Fairbanks turned exclusively to cos-

tume epics, such as The Mark of Zorro (1920) and Robin Hood

(1923). Chaplin discontinued short comedies and turned to

such features as The Gold Rush (1925) and The Circus (1927).

Mary Pickford turned from the “little girl” roles of Pollyanna

(1920) to more mature roles in Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall

(1925) and Coquette (1929), and Griffith, before his departure

in 1924, made two of his most successful films, Way Down

East (1920) and Orphans of the Storm (1922).

However, by 1925, UA’s finances were suffering from a rel-

ative lack of product. Quality was not the issue; more pictures

435

U

had to be made and released. Joseph Schenck became the

board chairman, and he brought an influx of new talent to

release pictures through UA, including

GLORIA SWANSON

,

RUDOLPH VALENTINO

,

WILLIAM S

.

HART

, and producer

SAMUEL GOLDWYN

. Pride of place among his stable of stars

was Norma Talmadge, whom he had married in 1917 and had

helped guide to stardom of the first magnitude by the early

1920s. Norma’s younger sister, Natalie, had married

BUSTER

KEATON

. It was only natural that Keaton, who had enjoyed

creative freedom in earlier years under Schenck (who released

his films through MGM) and who regarded him as a second

father, would follow him to UA (where he made three mas-

terly, but poorly received pictures, The General, College, and

Steamboat Bill, Jr.). A chain of theaters was organized in 1926,

the United Artists Theatre Circuit, Inc., which gave the com-

pany guaranteed exhibition spaces. UA’s first talking picture

release was Roland West’s Alibi (1929).

In the 1930s, the company became a packager for the films

of independent producers Walter Wanger,

DAVID O

.

SELZNICK

, and (in England) Alexander Korda. After some dif-

ficult times in the 1940s, the studio went through a series of

reorganizations. In 1950, Chaplin and Pickford sold off their

stock. In the late 1950s, UA went into the television syndica-

tion market by acquiring the Warner Bros. film library and the

RKO film library and by purchasing Ziv Television Programs.

It also branched out into music recording and publishing by

forming United Artists Records and United Artists Music.

A syndicate took over until 1967 when TransAmerica

Corporation bought the company. It was at this time that the

spectacular failure of Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1979)

weakened the company. In 1981, MGM acquired the studio

and formed a new company, MGM/UA Entertainment

Company. Entrepreneur Kirk Kerkorian took control. Five

years later, the conglomerate’s film library was purchased for

television by entrepreneur Ted Turner for more than $1.5

billion. Notable films released in the 1950–90 period

included The African Queen (1952), High Noon (1952), Some

Like It Hot (1959), the James Bond films of the 1960s, and

Rain Man (1988).

In 1988, MGM announced a $400 million restructuring,

selling a 25 percent interest to producers Guber-Peters-

Barris. Chairman Lee Rich and MGM chairman Alan Ladd

Jr. resigned. Later that year, MGM announced a $200 million

rights offering plus another restructuring. As part of the

restructuring, UA was closed down.

The next year, in 1989, Kerkorian bought back the

MGM/UA name, logo, headquarters and television opera-

tion. However, in 1990, Kerkorian sold MGM/UA to Pathé

Communications and its owner, Giancarlo Parretti, for $1.3

billion. In 1992, Parretti defaulted on a billion-dollar loan

from Credit Lyonnais. The bank took over the studio

through a corporate governance challenge.

In 1993, Frank Mancuso joined MGM and hired John

Calley, a Warner Bros. producer, to oversee the operation of

UA. Films such as The Birdcage and GoldenEye, the latter

being one of the new episodes of the James Bond series,

brought better days to UA. Nevertheless, the success rapidly

ebbed and once again, in 1996, Kerkorian acquired

MGM/UA from Credit Lyonnais and named Lindsay Doran

as head of UA.

From 1997 to 1999, United Artists had few releases with

little success: Hoodlum (1997) and The Rage: Carrie 2 (1999).

In 1999, UA celebrated its 80th anniversary by becoming

MGM’s specialty film unit that was focused on producing and

acquiring films with budgets of less than $20 million.

Today, United Artists Films exists as a vital specialty films

unit of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. Its recent critical and

commercial successes include Ghost World (2001), Tea with

Mussolini (1999), Leaving Las Vegas (1995), Tomorrow Never

Dies (1997), and The Man in the Iron Mask (1998), starring

LEONARDO DICAPRIO

. This movie set a record by opening in

3,101 theaters nationwide, the largest debut for a film in the

history of the company.

Universal Pictures One of Hollywood’s “Little Three”

motion picture companies (along with

UNITED ARTISTS

and

Columbia). Its formative years were presided over by the for-

midable

CARL LAEMMLE

. Having established by 1909 one of

the largest film exchanges in America, Laemmle turned to pro-

duction that year in defiance of the

MOTION PICTURE

PATENTS COMPANY

monopoly and established his own Inde-

UNIVERSAL PICTURES

436

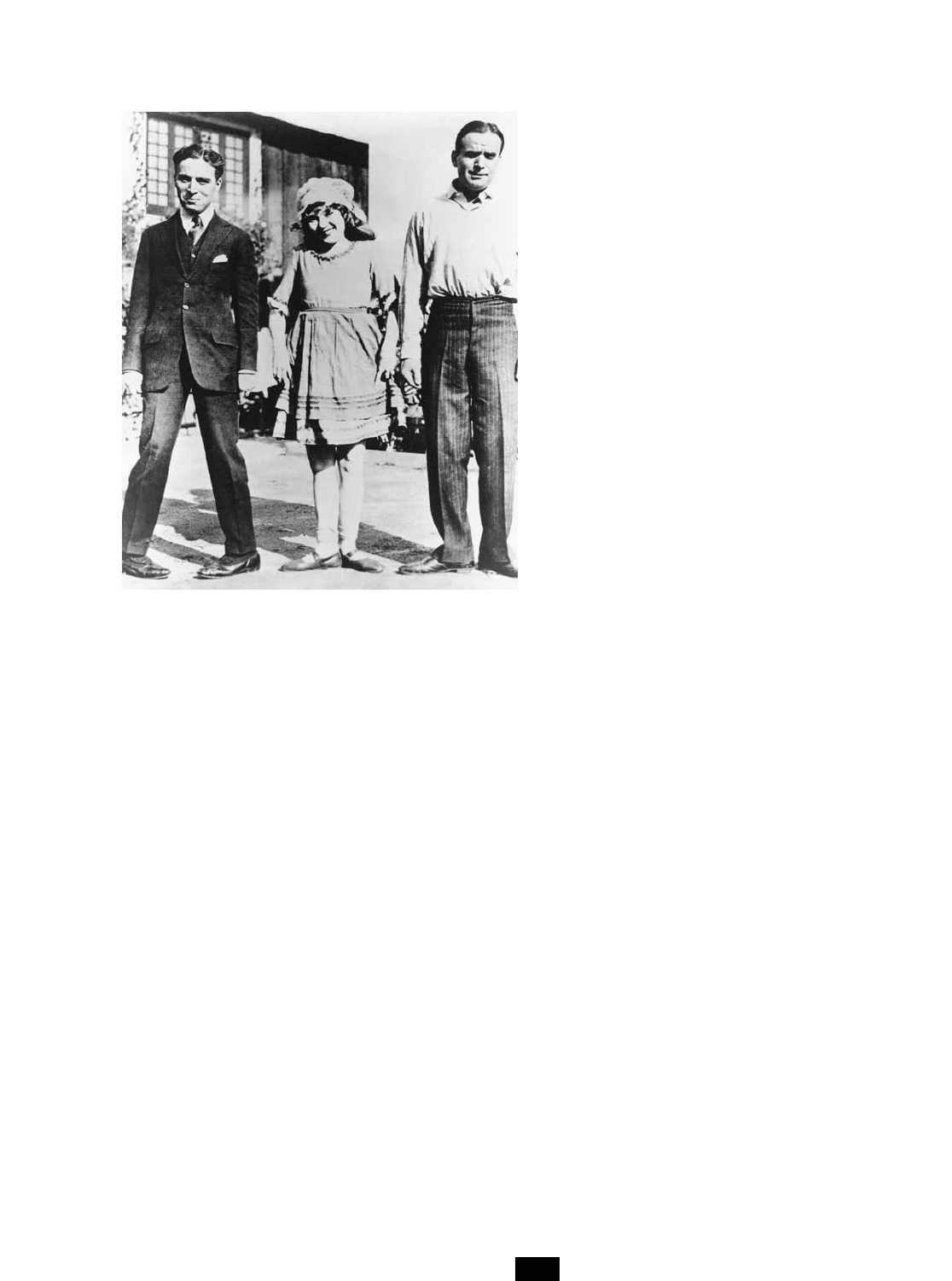

United Artists was founded in 1919. Three of the four

original stockholders are pictured here: Charlie Chaplin

(with the jacket), Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

The fourth founding member, director D. W. Griffith, had

a falling out with his partners and left the company in 1924.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF MOVIE STAR NEWS)

pendent Motion Picture Company. In 1912, he combined it

with several other companies to form The Universal (a name

he allegedly borrowed from the sign on a Universal Pipe Fit-

tings truck). Three years later, he opened the largest motion-

picture production facility in the world, Universal City, located

in the San Fernando Valley. It remains the oldest continuously

operating studio in America. The silent era was marked by

such emerging talents as director

ERICH VON STROHEIM

(Foolish Wives, 1922), production chief

IRVING THALBERG

, and

actor

LON CHANEY

. Future studio chief at Columbia,

HARRY

COHN

, got his start as one of Laemmle’s secretaries.

With the talking picture revolution and Universal’s first

all-talkie, Melody of Love in late 1928, Carl Laemmle Jr., was

appointed head of production. Several prestige pictures sub-

sequently appeared, including All Quiet on the Western Front

(1929) and Show Boat (1936). Laemmle Jr. also initiated one

of the studio’s most famous series of pictures, the horror

films—including Dracula (1930), Frankenstein (1931), and

The Invisible Man (1932). However, by the mid-1930s the stu-

dio was on the verge of financial collapse, and after Carl Jr.

was replaced by a series of other producers, including

Charles Rogers, the roster of releases reverted to mainly low-

budget programmers. These included the popular, cheery

DEANNA DURBIN

musicals, which helped the reorganized

company to begin to turn a profit and, later in the 1940s, the

Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes movies; low-budget come-

dies starring

W

.

C

.

FIELDS

, for example; and the

ABBOTT AND

COSTELLO

comedy team. It was also at this time that the stu-

dio took on a British partner, J. Arthur Rank.

In 1946, Universal merged with International Pictures.

Decca Records bought the company in 1952. It was absorbed

in 1962 by the former talent agency and communications

conglomerate created by Lew Wasserman, Music Corpora-

tion of America (MCA). Meanwhile, the studio began to

release packages of feature films to television. By now, the

movie output had been upgraded, ranging from a glossy

series of

DORIS DAY

vehicles to such blockbusters as Airport

(1970), The Sting (1973), Jaws (1975), and E.T. the Extra-Ter-

restrial (1982), at one time the top money-making film in

Hollywood history. In 1964, the Universal City Tours began.

In 1990, Universal opened a second studio in Orlando,

Florida, where tours are also conducted. The tours them-

selves are outgrowths of popular blockbuster films, like Back

to the Future and Jaws.

Since the early sixties, Universal had a steady life under

the leadership of its parent company, MCA. Popular and crit-

ically successful hits such as Field of Dreams (1989) set the stu-

dio style. However, by the end of 1990, Matsushita Electric

Industrial Company acquired MCA, paying $6.59 billion in a

deal that included MCA Television Group, MCA Records,

Geffen Records, Cineplex Odeon, and Universal Pictures. In

1995, Seagram’s Edgar Bronfman Jr. acquired MCA/Univer-

sal from Japan’s Matsushita, paying $5.7 billion for the media

company.

By the end of 2000, the French company Vivendi had

taken over Universal with the blessing of Seagram’s stock-

holders. One year later, Vivendi Universal, the new media

giant, merged Universal Pictures and Studio Canal with the

purpose of simplifying operations in Europe and the United

States. Each unit delimited its territory; thereafter, Studio

Canal would not have a hand in U.S. production anymore.

Therefore, such productions as

ROMAN POLANSKI

’s The

Pianist, Pradal’s Ginostra, and Mike Leigh’s Untitled ’01 were

all considered European projects, for obvious reasons.

During the nineties, Universal produced blockbusters

such as the Jurassic Park series and Schindler’s List (1993),

plus a larger variety of hits, including Apollo 13, Twelve Mon-

keys, The Mummy, and Primary Colors. More recently, Uni-

versal Pictures has released A Beautiful Mind (2001), The

Mummy Returns (2001), Harrison’s Flowers (2002) and the

remastered version of E.T. on its 20th anniversary. Universal

Studios has established successful theme parks in Hollywood

and in Orlando, Florida, and is planning a future park in

Osaka, Japan.

UNIVERSAL PICTURES

437