Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

During the 1960s, Warner released hit films such as My

Fair Lady (1964) and Bonnie and Clyde (1967), but by then the

studio had largely become a distribution network for inde-

pendent producers. For instance, in the 1970s and 1980s,

CLINT EASTWOOD

’s Malpaso Company released its films

through Warner Bros.

Meanwhile, in 1956, Harry and Abe Warner had sold

their stock, and Jack had become the only brother left asso-

ciated with the company. He sold his share to Seven Arts in

1967, which, in turn, was bought by Kinney National Service

in 1969, later changing the name of the conglomerate to

Warner Communications. In 1989 Time, Inc. merged with

Warner to become Time–Warner, Inc. At that time, the film

subsidiary scored successes with films such as Beetlejuice

(1988), Batman (1989), and Lethal Weapon II (1989).

At the end of August 1995, Ted Turner declared that

negotiations to merge Turner Broadcasting System with

Time-Warner were on their way. In those days Time-Warner

owned some 18 percent of TBS. The media giant intended to

pay $8 billion in stock to take over the remaining 82 percent.

Time-Warner acquired TBS on October 10, 1996. Time-

Warner/Turner, the new company, possessed a wide spec-

trum of media enterprises. Among the film studio companies

were Castle Rock Entertainment, New Line Cinema, Turner

Pictures, and Warner Bros. On the side of television, Time-

Warner/Turner owned HBO, the Cartoon Network, Turner

Classic Movies, CNN, CNN International, TNT, and

WTBS. The publishing branch included the magazines Peo-

ple, Sports Illustrated, Time, as well as Warner Books. Almost

50 labels accounted for the music companies, including

Warner and Atlantic. Six Flags theme parks, Warner Bros.

retail stores, and World Championship Wrestling also

became part of Time-Warner/Turner’s operations.

When America Online (AOL) acquired Time-

Warner/Turner, the merger became the largest one in his-

tory, creating the biggest media corporation in the world.

The cost of the deal: $163 billion. Recent films released by

Warner Bros. include Showtime (2002), Ocean’s Eleven (2001),

Collateral Damage (2001), A.I. (2001), The Perfect Storm

(2000), The Matrix (1999), Any Given Sunday (1999), and The

Matrix Reloaded (2003).

See also

BIOPICS

;

CURTIZ

,

MICHAEL

;

GANGSTER MOVIES

;

THE JAZZ SINGER

;

JOLSON

,

AL

;

MUSICALS

;

RIN

-

TIN

-

TIN

;

SOUND

;

WARNER

,

JACK L

.;

ZANUCK

,

DARRYL F

.

Warner Bros. cartoons Under the banner of Looney

Tunes and Merrie Melodies, they were the hippest, cleverest,

and most amusing animated shorts ever produced. With

characters such as Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig,

Elmer Fudd, Foghorn Leghorn, Tweety Pie, Sylvester the

Cat, Pepe LePew, Wile E. Coyote, Road Runner, and Speedy

Gonzales, the Warner Bros. animation unit was a perpetual

hotbed of creative lunacy.

Under the stewardship of Leon Schlesinger, Warner

Bros. began to make cartoons in 1930. These early black-

and-white films were called Looney Tunes to build on the

popularity of Disney’s Silly Symphonies. In addition, as

pointed out by Douglas Gomery in The Hollywood Studio Sys-

tem, “Warners insisted that each cartoon should include

music from a current Warners’ feature film.”

Throughout the early 1930s, the animation unit strug-

gled to make a reputation but without much success. It was-

n’t until Schlesinger launched Merrie Melodies, a color

cartoon series in 1934, that the Warner cartoons began to

catch on. More importantly, though, Schlesinger hired new

talent such as Tex Avery, Bob Clampett, Friz Freleng, Frank

Tashlin, and Chuck Jones, who, over time, developed the

famous Warner cast of cartoon characters. It began to take

shape in 1936 when Porky Pig made his debut and became

the first animated star on the Warner lot.

Bugs Bunny, the carrot-chomping wise-guy rabbit, was

created soon after, taking his name from the man who origi-

nally sketched him, Bugs Hardaway. The unnamed character

was simply referred to as Bugs’ Bunny in the early develop-

ment stage and, finally, the name simply took hold (minus the

apostrophe). While Bugs was the best-known character

among the Warner animated stars, Daffy Duck offered an

inspired insanity, and he remains a sentimental favorite of a

great many fans.

Two of the most influential animators at Warner during

its heyday were Friz Freleng and Chuck Jones who, between

them, helped create the frenetic action, violence, and goofy

humor that became a hallmark of their studio. The two of

them often produced and directed the Warner cartoons,

while many of the best of these animated shorts were written

by Michael Maltese.

From 1937, the voice of the Warner cartoon characters

was that of Mel Blanc until his death in 1989. His son learned

all the cartoon voices, however, and will continue in his

father’s voice prints.

Warner cartoons reached their creative height in the

1940s. By the middle of the decade both Looney Tunes and

Merrie Melodies were made in color, and while the anima-

tion was never quite on a par with Disney’s work, the Warner

cartoons offered far more energy and off-the-wall tongue-in-

cheek humor, making them especially entertaining for both

children and adults.

During the 1950s, Warner continued to make cartoons,

which appeared first in movie theaters and then on television,

where they have continued to thrive to this day. Unfortu-

nately, the Warner animation unit was disbanded in 1969, but

there have been Warner cartoon specials on TV throughout

the years, and Bugs and Daffy have been reborn in movie

shorts by a crew of new animators. The ultimate recognition

of the Warner cartoons occurred in 1987 when the animated

works were added to the permanent collection of the

Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

See also

ANIMATION

.

Warner, Jack L. (1892–1978) Of the four brothers

who founded the motion picture company that bore their

family name, he was the best known. As chief of production

at the Warner Bros. Burbank studio, Jack Warner oversaw

the producers, stars, directors, and writers who created many

WARNER BROS. CARTOONS

448

of the most memorable movies of the studio era. Jack Warner

was not the brightest of the Warner brothers—that distinc-

tion belonged to the firm’s president, Harry, who controlled

the company purse strings from New York. Nor was Jack

Warner a visionary; brother Sam was the one among them

who pursued the dream of talking pictures. Albert was the

swing vote who usually backed Harry. But Jack was the only

brother who had a real feel for entertainment. He loved to

sing and tell jokes (usually bad ones), and he had a genuine

love of entertainers, many of whom he idolized.

Jack Warner was the youngest of 14 children born to a Pol-

ish immigrant family. Warner, himself, was born in Canada

while his family restlessly looked for a place to settle in North

America, finally putting down roots in Youngstown, Ohio.

When the Warner family invested in a nickelodeon in

Newcastle, Pennsylvania, in 1903, Jack was out front during

intermission singing to the customers. It was as close to

vaudeville as he’d ever get.

He joined with three of his brothers to continue in the

movie business but met with only variable success during the

silent era. Once their studio was firmly established in the late

1920s (thanks to The Jazz Singer, 1927), Jack ruled over film

production with an iron hand. Of all the major studios, Jack

Warner ran his studio, more than any other, like a factory,

churning out movies with the speed and efficiency of a fast-

moving production line, but unlike most other Hollywood

studio moguls, Jack Warner didn’t forget the poverty he once

knew. He promoted pictures with a social consciousness,

such as I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932) and Wild

Boys of the Road (1933).

A supporter of Franklin Roosevelt, Jack stood up for

Democratic causes throughout the 1930s and was a vigorous

backer of the war effort, starting as a major in the army sig-

nal corps and eventually becoming a colonel.

In 1956, when his surviving brothers, Harry and Albert,

sold their shares of the company, Jack stubbornly refused to

sell out. The old dinosaur continued running the company

until 1967, when he sold his shares to Seven Arts. In the

meantime, he had been duly honored by the Hollywood

community during the 1958 Oscar ceremonies when he was

presented with the prestigious Irving G. Thalberg Memor-

ial Award.

During Warner Bros.’ heyday, Jack Warner delegated

much of the production detail to such talented right-hand men

as

DARRYL F

.

ZANUCK

and

HAL B

.

WALLIS

. Toward the end of

his reign as studio chief and in the years thereafter, he proved

that he was an equally capable producer. He personally pro-

duced such hits as My Fair Lady (1964) and Camelot (1967), as

well as the entertaining musical flop 1776 (1972) and the sur-

prisingly offbeat, gritty western Dirty Little Billy (1972).

Jack Warner outlived all his brothers and, except for Dar-

ryl F. Zanuck, he was the last of the great movie moguls to

pass from the American scene.

See also

WARNER BROS

.

Warren, Harry (1893–1981) A prolific and hugely

successful composer and songwriter who wrote tunes for

Hollywood for nearly 50 years. According to the American

Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers, Warren is

the seventh best-selling songwriter of all time, and his long

list of movie musical classics attests to his popularity. He

helped three studios reach their respective musical heights,

writing tunes for

WARNER BROS

.’ greatest musicals of the

early to mid-1930s,

TWENTIETH CENTURY

–

FOX

’s

ALICE

FAYE

period in the late 1930s and early 1940s, and the begin-

ning of MGM’s musical golden era in the mid- to late 1940s.

He also contributed to Paramount’s successful musical come-

dies of the early 1950s. Winner of three Oscars, Warren’s

musical style was well suited to the movies: It was bold,

brassy, and elegantly simple; audiences could (and did) hum

the songs he wrote when they left the theater.

Born Salvatore Guaragno in Brooklyn, New York, he

made his way in Hollywood any way he could, working as an

extra and a propman, finally managing to become an assistant

director, but all the while he was writing music, and after

penning a hit song in the 1920s, he was set on his true career.

After a few Broadway shows, Warren returned to Holly-

wood. Sound had come to the movies, and musicals were

much in demand. At Warner Bros., working with lyricist Al

Dubin (Dubin was his first and most notable collaborator),

Warren wrote the songs for the classic musicals 42nd Street

(1933), Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), Footlight Parade (1933),

Dames (1934), Wonder Bar (1934), and others, creating stan-

dard tunes that are still much loved today.

When Warner Bros. lost interest in the musical, Warren

went to Fox, where he wrote the scores for such entertaining

films as Down Argentine Way (1940), Tin Pan Alley (1940), Sun

Valley Serenade (1941), Hello Frisco Hello (1943), and Sweet

Rosie O’Grady (1943).

At MGM, Warren helped develop the great musical tra-

dition that would flourish at the studio in the late 1940s and

1950s with songs for, among others, The Harvey Girls (1946),

Ziegfeld Follies (1946), and Summer Stock (1950).

He began to slow down in the 1950s and 1960s, but he

still managed to write hit songs for films such as the Martin

and Lewis vehicles The Caddy (1953) and Artists and Models

(1956). His last movie music could be heard in Rosie (1967).

Just a small sampling of Warren’s enormous output of hits

(exclusive of title songs from many of the previously men-

tioned films) are “Lullaby of Broadway,” “I Only Have Eyes

for You,” “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby,” “Jeepers

Creepers,” “Chattanooga Choo Choo,” “The More I See

You,” and “That’s Amore.”

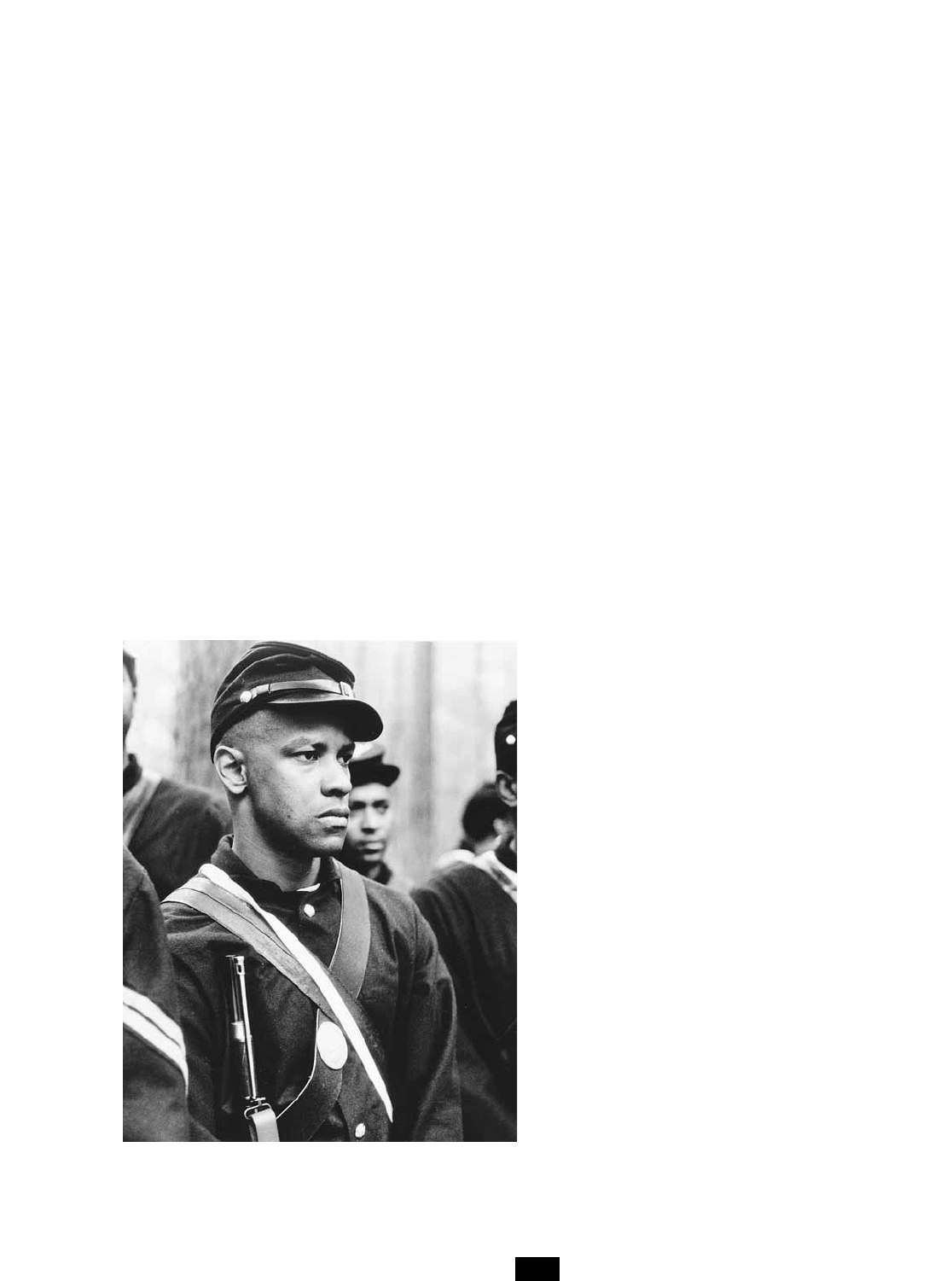

Washington, Denzel (1954– ) Few African-Ameri-

can entertainers ascended to superstar status in 20th-century

America, but Denzel Washington surely broke the color bar-

rier most effectively and absolutely, following the lead of

Harry Belafonte, Sammy Davis Jr.,

SIDNEY POITIER

, and

MORGAN FREEMAN

. One of Washington’s first film roles was

that of Pfc. Melvin Peterson in

NORMAN JEWISON

’s A Soldier’s

Story, adapted in 1984 by Charles Fuller from his critically

acclaimed Pulitzer Prize winner, A Soldier’s Play. Washington

was a natural casting choice because he had already played the

WASHINGTON, DENZEL

449

role onstage for the Negro Ensemble Company. A Soldier’s

Story was a benchmark film, demonstrating that a major stu-

dio such as

COLUMBIA PICTURES

could risk making a race-

themed movie and still expect a reasonable crossover

audience to realize a profit. A Soldier’s Story, which also

starred Howard E. Rollins Jr. and Adolph Caesar, was bud-

geted at $5 million, but the film was so successful that it made

more than $30 million and won Academy Award nomina-

tions. Denzel was part of a gifted ensemble that included

Robert Townsend and Larry Riley, but he was also unforget-

table, as witnessed by the Obie Award he won for his work in

the Negro Ensemble Company’s Off-Broadway production.

Experience had primed him for the role by the time the cam-

eras started turning.

Denzel Washington was born on December 28, 1954,

and grew up in Mount Vernon, New York, the son of a Pen-

tecostal preacher from Virginia and a former gospel singer

who had been born in Georgia but raised in Harlem. After

winning a scholarship to the Oakland Academy in upstate

New York, he went on to Fordham University in 1972. At

Fordham, he played the lead on stage in The Emperor Jones,

and he later auditioned for—and got—the role of Malcolm X

for a Federal Theatre Project production of When the Chick-

ens Come Home to Roost, but his first break would not come

until 1977 in the made-for-television film Wilma, starring

Cicely Tyson in a biopic about the track-and-field Olympic

star Wilma Rudolph. His first feature film, Carbon Copy

(1981), a comedy in which Denzel played

GEORGE SEGAL

’s

illegitimate son, was nothing to boast about. His next fea-

ture-film role, however, would be in the aforementioned A

Soldier’s Story.

Of course, success didn’t come all at once. Washington

paid his dues on NBC television, playing Dr. Phillip Chan-

dler on the St. Elsewhere series from 1982 to 1984. By the

final season, Denzel was making nearly $30,000 an episode,

but he was careful to avoid being typecast for the movie roles

that came his way. In

SIDNEY LUMET

’s Power (1986), he took

a villainous supporting role behind

RICHARD GERE

and

GENE

HACKMAN

in the political allegory. He played the South

African activist Steve Biko for Sir Richard Attenborough in

the antiapartheid film, Cry Freedom (1987), and found himself

with an Oscar nomination, but the film, based upon the rela-

tionship of Biko with the journalist Donald Woods (Kevin

Kline), was not a commercial success. Washington consid-

ered it something of a cop-out: “Cry Freedom was disappoint-

ing to me because it was supposed to be about Steve Biko,”

he complained. “It shouldn’t have been compromised by

making it Donald Woods’s movie.”

After traveling to England to appear in For Queen and

Country (1988), followed by the lead role in The Mighty Quinn

(1989), costarring his friend Robert Townsend, Washington

took a lesser role in the Civil War feature Glory (1989),

costarring with Matthew Broderick, Morgan Freeman, and

André Braugher, but he still ended up with an Academy

Award. (Another Oscar would come for Training Day in 2001,

with several nominations in between.) Glory was about a

black regiment that was decimated in the Civil War, but the

main character seemed to be Robert Gould Shaw (Broder-

ick), who organized the 54th Massachusetts to fight the

rebels. In 1990, Washington was cast as the trumpet player in

Spike Lee’s Mo’ Better Blues, intended to look like John

Coltrane but sound like Miles Davis. His next film role was

not well chosen: Heart Condition (1990) was a critical and

commercial failure. This was followed by Ricochet (1991),

another critical failure; Washington is on record objecting to

the film’s “mindless violence.”

A kinder, gentler role offered itself for his next project in

Mississippi Masala (1992), directed by Mira Nair and con-

cerned with an interracial romance in the American South,

but this was followed by Spike Lee’s invitation to play the

title role in Malcolm X (1992), Lee’s overlong tribute to the

slain iconic black leader. A more comfortable fit for the

actor, perhaps, was the role of Easy Rawlins in Devil in a Blue

Dress (1995), adapted by legendary black director Carl

Franklin from the detective novel by Walter Mosley. Could

any other black actor have commandeered the

CARY GRANT

role in the remake of The Bishop’s Wife (1947), retitled The

Preacher’s Wife, for its 1996 Christmas release? Well, Wash-

ington did.

The variety of roles that Washington has played is

impressive, ranging from his turn as Don Pedro in Kenneth

Branagh’s Much Ado about Nothing (1993), to Joe Miller, the

lawyer who agrees to represent an AIDS patient in Philadel-

phia (1993), to Lt. Cmdr. Ron Hunter in Crimson Tide (1995),

WASHINGTON, DENZEL

450

Denzel Washington in Glory (1989) (PHOTO COURTESY

TRI-STAR PICTURES)

followed by Lt. Col. Nathaniel Serling in Courage under Fire

(1996), to supercop Parker Burns in Virtuosity (1995), to his

FBI agent in The Siege (1998), to the quadriplegic detective in

The Bone Collector (1998), to the boxer Rubin “Hurricane”

Carter in The Hurricane (2000), to football coach Harrison

Boone in Remember the Titans (2000).

Denzel Washington, whose stellar abilities commanded

$12 million a picture by the end of the 20th century, has

become a bona-fide American everyman, a transformation

that no other black actor has so far managed. In fact, he

played an everyman type in John Q. (2002), which Variety dis-

missed as a “shamelessly manipulative commercial on behalf

of national health insurance,” costarring James Woods and

ROBERT DUVALL

. The fact that John Q. Archibald happens

to be a hard-working and sincere African American is almost

beside the point. He was, above all, a sympathetic blue-collar

citizen whose son badly needed medical attention. Variety’s

Todd McCarthy, who started his review on a cynical note,

admitted that “[d]espite all the simplifications, Washington

creates a credible characterization of a decent, working-class

man driven to extremes.” Biographer Douglas Brode may be

right in claiming that mixed audiences “don’t consciously

think of Denzel’s characters as black.” Hence

ALAN J

.

PAKULA

put him on a level playing field with

JULIA ROBERTS

in The

Pelican Brief (1993), and the formula and chemistry worked

beautifully. The same year that John Q. was released saw

Washington also make his directorial debut with Antwone

Fisher. At midcareer, then, Denzel Washington is certainly a

well-established star at the top of his game.

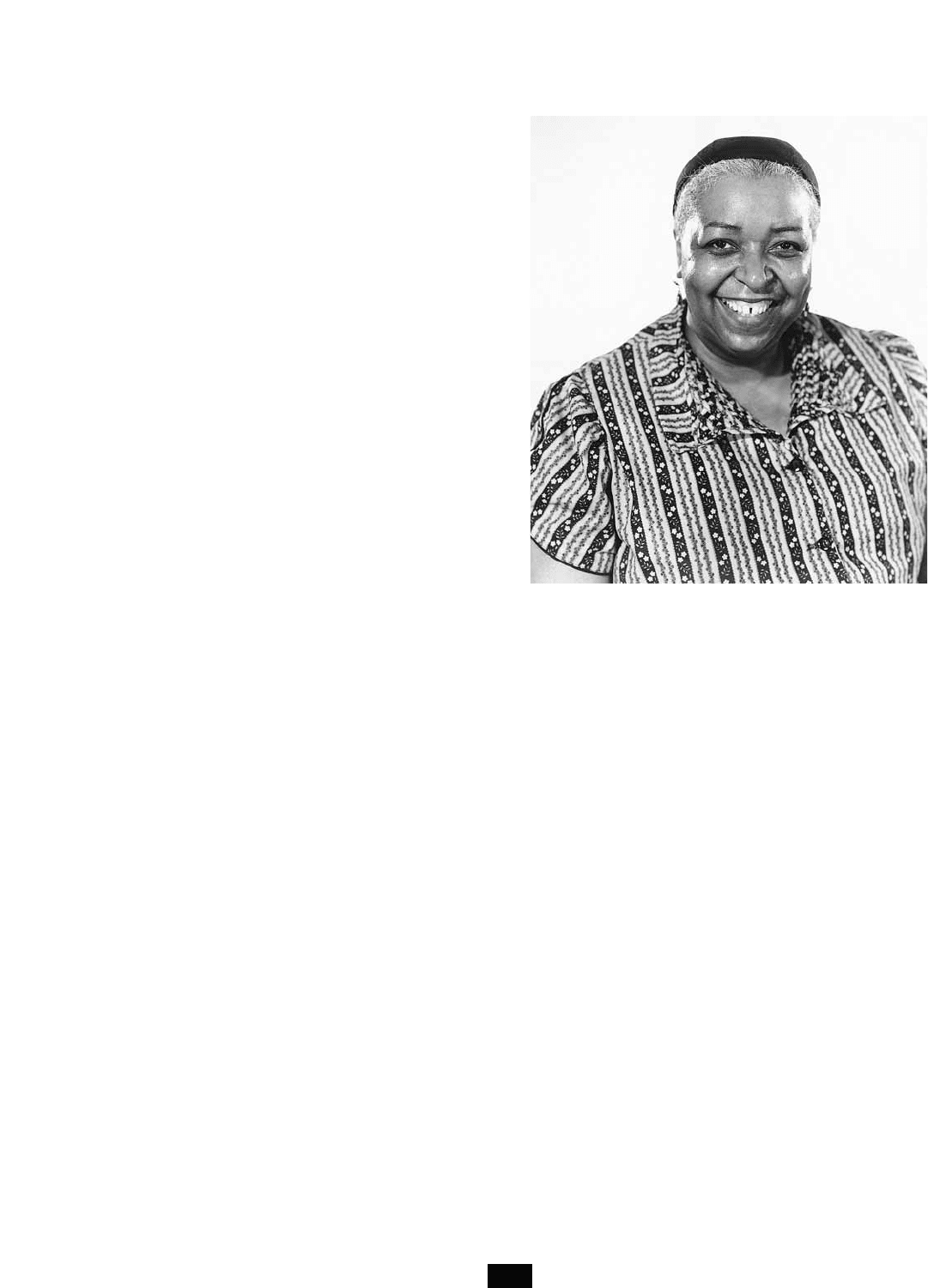

Waters, Ethel (1896–1977) A black singer/actress

who commanded the screen in the relatively few opportuni-

ties Hollywood offered her. Waters had dignity and power,

and those very attributes limited her movie career during the

less tolerant years that made up the bulk of her lifetime.

Nonetheless, she appeared in 10 films, making the most of

her screen time.

Waters was married at the age of 12 (she would marry a

total of three times) and worked at menial jobs before she

made a name for herself as the singer Sweet Mama String-

bean when she was 17. Working in vaudeville and later help-

ing to break the color barrier on Broadway, Waters became

one of the leading black singer-actresses in America.

Her appearances on film were often directly tied to her

successful Broadway shows. Two of her three best-known

movies had been stage hits that were turned into the films

Cabin in the Sky (1943) and The Member of the Wedding (1952).

The third was a film about racism, Pinky (1949), for which

she was honored with an Oscar nomination for Best Sup-

porting Actress.

It was in such movies as On with the Show! (1929), her

debut film, when she sang “Am I Blue?” and “Birmingham

Bertha” (both numbers were designed to be so tangential to

the plot that they could be easily edited out when the film was

circulated in southern cities), and in her starring role in Cabin

in the Sky, that film audiences were given a taste of her sexy,

sassy blues interpretations.

Most of her films, however, weren’t musicals, and Waters

bowed out of Hollywood after her appearance in The Sound

and the Fury (1959).

See also

RACISM IN HOLLYWOOD

.

Waxman, Franz (1906–1967) A film composer who

excelled at writing dark, moody music tinged with hints of

danger. No wonder, then, that his scores for Sunset Boulevard

(1950) and A Place in the Sun (1951) won Oscars. In fact, the

majority of his scores were for films that fit the gothic, hor-

ror, suspense, mystery, and thriller genres.

Born Franz Wachsmann in Germany, he studied music at

the Dresden Music Academy and the Berlin Music Conser-

vatory. His film career began in 1930 when he started to

arrange and then compose music for films at UFA, the Ger-

man film company. Jewish, he was physically attacked and

beaten by Nazi sympathizers in 1934, whereupon he fled to

Paris. He arrived in America soon thereafter and found a

home in Hollywood, where a great many German refugees

made him welcome.

His first film score in Hollywood was for The Bride of

Frankenstein (1935), and its sinister and brooding feeling set

WAXMAN, FRANZ

451

Ethel Waters was known as “Sweet Mama Stringbean”

when she started in show business at the age of 17. She rose

to fame as a singer and became known to movie audiences

in a modest number of motion pictures, many of which she

dominated with her warm, powerful personality.

(PHOTO

COURTESY OF THE SIEGEL COLLECTION)

the tone for much of his later work. Other than the magnifi-

cent Bernard Herrmann, Waxman was

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

’s

favorite composer, writing the scores for four films made by

the “master of suspense,” Rebecca (1940), Suspicion (1941), The

Paradine Case (1948), and Rear Window (1954).

Waxman was prolific, writing more than 50 film scores,

his greatest impact occurring during the

FILM NOIR

period of

the late 1940s and early 1950s. In particular, his music for

such films as The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947), Possessed (1947),

Dark Passage (1947), The Unsuspected (1947), and Sorry Wrong

Number (1948) helped immeasurably to create the paranoia

that infested these and other films of that era.

Of course, Waxman didn’t write moody music all the

time. Among his lighter efforts were the scores for such films

as the

MARX BROTHERS

’ A Day at the Races (1937), A Christ-

mas Carol (1938), The Philadelphia Story (1940), Woman of the

Year (1942), Air Force (1943), Mister Roberts (1955), Taras

Bulba (1962), and many others. The last film he scored was

Lost Command (1966).

In addition to his work in the movies, Waxman created

and nurtured the Los Angeles Music Festival in 1947, an

institution that has developed an international reputation.

Wayne, John (1907–1979) An actor who became a

folk hero for his portrayal of rugged, independent Americans.

During a career of nearly 50 years, he was the most consis-

tently popular performer in postwar Hollywood, landing in

the top 10 in box-office polls in 19 of 20 years between 1949

and 1968 (he missed the top 10 in 1958 when he bombed in

The Barbarian and the Geisha). As a consequence of his popu-

larity, his films brought in a staggering $800 million in box-

office receipts, which, in constant dollars, remains a record.

Big, broad shouldered, and square jawed, Wayne was an

imposing figure on film, but he also possessed a boyish charm

that hardened into a vulnerable dignity as his face weathered

with age. For the most part, Wayne will be remembered for

the many movies in which he collaborated with one of Hol-

lywood’s greatest directors, John Ford.

He was born Marion Michael Morrison in Winterset,

Iowa, to a druggist father. Ill health caused his father to move

the family to Southern California, where his strapping young

son excelled in both his studies and in sports. It was during

Wayne’s youth that he made regular visits to a local fire-engine

station, accompanied by his pet airedale, Duke, which led to

his nickname of Big Duke, later shortened simply to Duke.

A football scholarship sent Wayne to the University of

Southern California, where he played football for two years

before a shoulder injury, sustained while surfing, ended his

athletic career. While in college, Wayne worked summers at

the Fox Studio prop department, getting the job through a

contact with

TOM MIX

. During 1926, while at Fox, he met

and befriended director John Ford, who occasionally put his

young friend in scenes didn’t require any acting, in several

different movies such as Mother Machree (1928), in which

Wayne made his debut, and Hangman’s House (1928).

In 1929,

RAOUL WALSH

needed a star for his western epic

The Big Trail.

GARY COOPER

was unavailable and filming was

about to begin. Reports are mixed, but either John Ford rec-

ommended Wayne to play the lead in the film or Walsh sim-

ply spotted him on the Fox lot and decided to offer him the

starring role after giving him a screen test. It was for The Big

Trail that Marion Michael Morrison became John Wayne, a

name created in collaboration with Walsh and director

Edmund Goulding. “Wayne” came from General “Mad

Anthony” Wayne of Revolutionary War fame, and “John” was

a solid name that seemed simply to go nicely with “Wayne.”

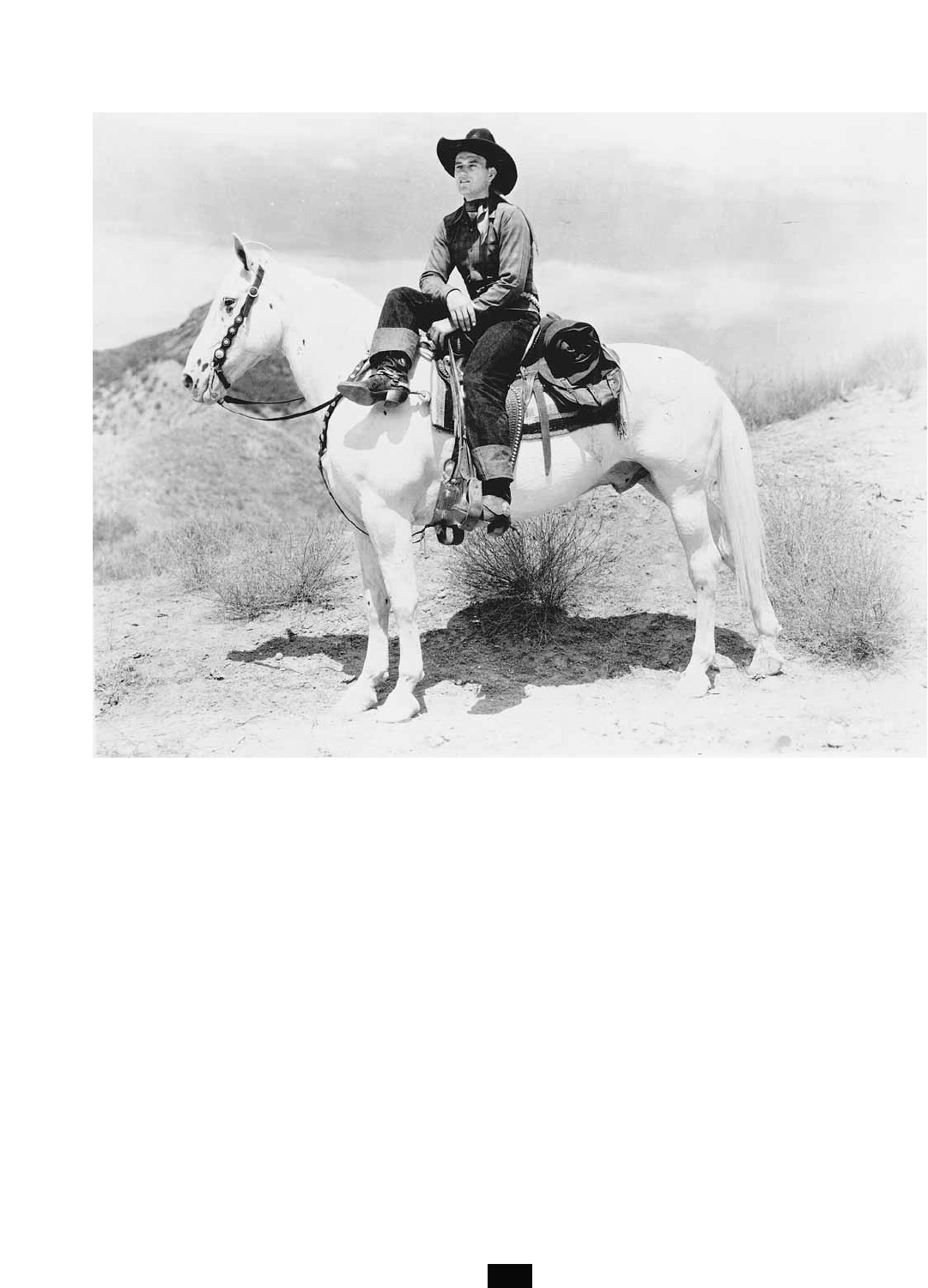

The new moniker didn’t help The Big Trail, which was a

major commercial flop. Wayne continued to act but in

increasingly minor movies until he settled in, first at the

poverty-row studio Mascot, followed by Monogram, and

then finally Republic, making serials and low-budget action

films, among the latter Riders of Destiny (1933), Randy Rides

Alone (1934), and The Three Mesquiteers (1938). He even took

a stab at being a singing cowboy, playing “Singing Sandy”

Saunders in one western (both his guitar playing and singing

were dubbed). He starred in the neighborhood of 200 of

these quickie oaters and low-grade movies; nobody knows for

sure how many.

For many years, John Ford had promised Wayne that he’d

give him a role in one of his films. After Gary Cooper turned

down the role of the Ringo Kid in Stagecoach (1939), Ford

made good his promise, giving Wayne the break of his career.

Stagecoach was a huge hit, and Wayne suddenly became a star

after having spent a decade in the Hollywood boonies. He

went on to star in 14 films directed by Ford, many of them

some of the director’s greatest works, including She Wore a Yel-

low Ribbon (1949), The Quiet Man (1952), The Searchers (1956),

and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).

Wayne was often considered a poor actor, but in fact he was

exceptionally good at playing John Wayne, and he played that

character—tough, prideful, and noble—with a considerable

variety of interpretations. He played him young and cocky in

Seven Sinners (1940), old and stubborn in Red River (1948),

independent and proud in Rio Bravo (1958), and vulnerably ide-

alistic in The Three Godfathers (1948). Except for his many west-

erns, which made up nearly half of his movies after Stagecoach,

Wayne was perhaps best known for his patriotic hard-as-nails

image in any number of war films, most notably The Fighting

Seabees (1944), They Were Expendable (1945), Sands of Iwo Jima

(1949), for which he received his first Best Actor Academy

Award nomination, and the Vietnam War–era The Green Berets

(1968), a controversial film that he also produced and directed

to critical catcalls but big box office. Of this latter film, it is

often noted that Wayne filmed the sun setting in the east.

In addition to starring in films, Wayne also produced a

great many movies, first at Republic and later through his

own company, Batjac Productions. Among those films he

produced were Angel and the Badman (1947), The Fighting

Kentuckian (1949), Hondo (1953), The High and the Mighty

(1954), Blood Alley (1955), and The Alamo (1960), which also

marked his debut as a director.

By the late 1960s, Wayne seemed to be an actor in a time

warp. His massive body lumbered through films that seemed

out of step with the rest of Hollywood. He reportedly had to

be lifted by crane to get up in the saddle of his horse. But his

WAYNE, JOHN

452

movies made money, even if they were mostly ignored by the

critics except to say “another John Wayne movie.” Only a few

of his later films were memorable, such as El Dorado (1967),

True Grit (1969), which brought him his only Best Actor

Oscar, and his final film, The Shootist (1976).

No actor has taken his last bow on film as movingly as

Wayne. The Shootist begins with a montage of scenes of

Wayne in his earlier westerns, ostensibly giving us the his-

tory of the film’s main character but really telling us that

this story is about the movie icon John Wayne. In the

course of the film, Wayne teaches a young man (

RON

HOWARD

) the Code of the West. When Wayne dies at the

end in a shootout (knowing all along that he is dying of

cancer), taking a saloonful of villains with him, we know

that we’ve seen the last of this particular brand of Ameri-

can hero.

The courage Wayne showed on screen in his many films

was matched by his endurance under the doctor’s knife. In

1963, he survived lung cancer, having one of his lungs

removed. Later, in 1978, he had open-heart surgery, and in

1979, cancer returned, leading to more surgery. He died

shortly thereafter. In honor of his passing, he became one of

the rare actors to ever have a congressional medal made in

his likeness.

See also

FORD

,

JOHN

;

HAWKS

,

HOWARD

;

SIEGEL

,

DON

-

ALD

;

SERIALS

;

STAGECOACH

;

WAR MOVIES

;

WESTERNS

.

Weaver, Sigourney (1949– ) Sigourney Weaver, the

daughter of NBC programming head Pat Weaver, led a priv-

ileged youth in New York City. Tall and nerdy in her fresh-

man year of high school, she transformed herself by changing

her name from Susan to Sigourney, a minor character in

Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and by becoming a class clown.

At Stanford University, she majored in English and acted in

university and community drama groups, taking on roles in

WEAVER, SIGOURNEY

453

John Wayne toiled in low-budget westerns and serials throughout the 1930s before becoming a star in John Ford’s Stagecoach

(1939). He is seen here in one of his many early cheapies.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF MOVIE STAR NEWS)

Shakespeare’s The Tempest and King Lear; but she was also

active in guerrilla theater, playing the title role in Alice in

ROTCland at the football stadium. At the Yale Drama School,

which Robert Brustein headed, she acted in some plays and

met colleagues such as playwright Christopher Durang, in

whose Off-Broadway play The Nature and Purpose of the Uni-

verse she appeared. She also was in Joseph Papp’s troupe in

New York and appeared in the Off-Broadway play Marco Polo

Sings a Solo. Television work in The Best of Families and Som-

erset followed, as well as a walk-on part in

WOODY ALLEN

’s

Annie Hall.

When she was cast as Ripley, in a part originally written

for a male, in Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), she seemed to have

made it, cinematically, because the film was a smash hit; but

her career seemed stalled, and she returned to the theater,

appearing in a production of Beyond Therapy in New York.

Her role opposite

MEL GIBSON

in The Year of Living Danger-

ously (1983) again seemed to establish her in Hollywood, but

Linda Hunt, who played a man in the film, received all the

accolades. Deal of the Century (1983), with

CHEVY CHASE

,

failed critically and financially, but Ghostbusters (1984), in

which she played a siren, allowed her to recover and estab-

lished her comedic talents. She was nominated for a Tony for

her role in David Rabe’s Hurlyburly, but she could not find

parts in Hollywood. Her next two films were made abroad. In

Half Moon Street (1986), shot in England, she played Dr. Lau-

ren Slaughter, a complicated, bright, witty, and gorgeous

woman of the ’80s. The film did well in Europe but not in the

United States, where it received little distribution and was

panned by critics. One Woman or Two (1986), shot in France,

also did well enough in Europe, but possibly because of the

subtitles (an international cast, including Gerard Depardieu,

was used), the film did not do well in the United States.

By contrast, however, Aliens (1986) did very well indeed.

In the sequel to Alien, she again played Ripley, but her role

was expanded and given more complexity, and in the course of

the film, she succeeded in transforming the burned-out Rip-

ley to a powerful leader. For her role in the blockbuster film,

she received plaudits from reviewers (one Rolling Stone critic

wrote that she “gives this programmed movie rawness and

life,” and Time put her on the cover of their July 28, 1986,

issue). She was nominated for an Oscar. In Alien 3 (1992), she

again reprised her Ripley role in what was to be the final

installment of the series. She did well in comedy features too.

Ghostbusters II (1989) was a comic diversion that did well at the

box office but mainly because of Bill Murray and

DAN

AYKROYD

. Perhaps her best comic performance was in Galaxy

Quest (1999), a spoof of Star Trek and Trekkie conventions.

Weaver has had her share of “serious” roles. She was

again nominated for an Oscar and won a Golden Globe for

her performance in Gorillas in the Mist (1988), in which she

played the role of animal rights activist Dian Fossey, intent

upon protecting “her” gorillas in Africa. In 1994, Weaver

convincingly played the raped and tortured victim of a South

American dictator in Death and the Maiden, directed by

ROMAN POLANSKI

. In 1997, she played the emotionally reck-

less wife and mother in Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm. She received

the British Academy award as Best Supporting Actress and

was also nominated for a Golden Globe. Her first 28 films

grossed some $979 million, indicating her box-office drawing

power. Weaver has since starred in Alien: Resurrection (1997),

reprising the role of Ripley which made her famous, Galaxy

Quest (1999), Heartbreakers (2001), and Holes (2003).

Webb, Clifton (1891–1966) A gifted and versatile

performer whose movie roles were generally limited to

pompous, upperclass, acid-tongued individuals. Webb some-

times played his archetypal character in dramatic films, but

he usually starred (often as the stuffed shirt babysitter, Mr.

Belvedere) in successful comedies during the late 1940s and

throughout the 1950s.

Born Webb Parmalee Hollenbeck, he began to dance

and act professionally while still a child. Not content with

his lot in life, he studied painting and music, briefly becom-

ing an opera singer when he was just 17. Then came a suc-

cessful career as a ballroom dancer, which led to jobs in

Broadway musicals in the late 1910s. He soon proved his

mettle as a serious actor, as well, gaining a fine reputation in

the English theater.

Tall and trim with a handsome countenance, he was a nat-

ural for the movies, which beckoned in the early 1920s. He

graced a number of films, among them Polly with a Past

(1920) and The Heart of a Siren (1925), but the peripatetic

actor did not become a silent movie star.

Webb returned to the stage and continued to cultivate his

many interests when, nearly two decades after his last film

appearance,

OTTO PREMINGER

decided he wanted Webb as

the sophisticated killer in Laura (1944). Though Preminger’s

boss at

TWENTIETH CENTURY

–

FOX

,

DARRYL F

.

ZANUCK

,

was dead set against hiring Webb, Preminger finally pre-

vailed. In the end, Laura became a smash hit, and Webb was

nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his per-

formance. He also became a character actor and star at Fox

and, ultimately, even became a very close friend of Zanuck’s.

In Hollywood films, where intellectuals were so often

looked on with distrust, Webb’s uppercrust, snobby, know-it-

all persona was a natural for antagonist roles. He played the

villain in The Dark Corner (1946) and a less-than-likeable

character in The Razor’s Edge (1946), which brought him

another Best Supporting Actor Academy Award nomination.

Then, something peculiar happened: Webb was cast as

the stuffy, pedantic babysitter, Mr. Belvedere, in Sitting Pretty

(1948) and stole the movie from its child stars (no easy feat).

The movie was a huge hit, and the actor went on to star in

several films, playing the same character. Once he was seen as

a lovable stuffed shirt, he was given similar lead roles in films

such as Cheaper by the Dozen (1949), Mister Scoutmaster

(1952), The Remarkable Mr. Pennypacker (1958).

He retired from the screen in 1962 after starring in an

unsuccessful drama, Satan Never Sleeps, in which he played an

anticommunist priest.

Weissmuller, Johnny (1904–1984) Though not the

first man to play Tarzan on film, he was undoubtedly the

WEBB, CLIFTON

454

best—and certainly the most fondly remembered. Weiss-

muller was a wooden actor with a halting speech pattern that

worked just fine for the monosyllabic role of the ape man cre-

ated by Edgar Rice Burroughs. His limitations as an actor

were more readily apparent when he grew a bit long in the

tooth to play Tarzan and starred in the low-budget Jungle

Jim series. Called upon to speak in the somewhat more

sophisticated tones of a jungle guide, Weissmuller was only

marginally more articulate than he had been as Tarzan. How-

ever, for generations who saw Weissmuller swinging from

vines on the big screen, and for their children who saw him

doing the same when the movies were rebroadcast on televi-

sion, Weissmuller would always be Tarzan.

Born Peter John Weissmuller, the young athlete became

a gold medal winner for the United States during the 1924

Olympics, and then he did it all over again in 1928, winning

a total of five gold medals. As a celebrated sports star, he was

lured into appearing in a few short subjects, but it wasn’t until

MGM decided to star him in Tarzan, the Ape Man (1932) that

an institution was born. The film had high production values,

a good script, and a strong supporting cast (including Mau-

reen O’Sullivan as Jane) behind Weissmuller’s surprisingly

bold, if stiff, performance. Weissmuller, who almost always

showed off his famed swimming prowess in at least one scene

in every film, starred in a total of 12 Tarzan movies, the first

half of them for MGM, the second set of six for RKO. The

best of these films were at MGM, and Tarzan and His Mate

(1934) is considered by most as the cream of the crop.

Weissmuller was 44 years old when he hung up his loin-

cloth and made his last Tarzan film, Tarzan and the Mermaids

(1948). He immediately went to

COLUMBIA PICTURES

and

began to star in a series of low-budget adventure films for

kids that began with Jungle Jim (1948). He continued to play

the same character in a total of 16 of these films (although in

the last three, all pretense was dropped, and his character was

called Johnny Weissmuller).

Except for one role in 1946, in a mediocre film called

Swamp Fire, Weissmuller played either Tarzan or Jungle Jim

exclusively through 1955. Curiously, his costar in Swamp Fire

was Buster Crabbe, another former champion swimmer who

had played Tarzan in a film produced by a competing studio

during the 1930s.

After a short stint as Jungle Jim on TV, Weissmuller quietly

retired. Like fellow swimmer/actor

ESTHER WILLIAMS

, he lent

his name to a pool company and did reasonably well in busi-

ness. He fared less well at marriage, marrying six times. His

last movie appearance was a cameo role in The Phynx (1970).

Welles, Orson (1915–1985) He was the boy genius

and enfant terrible who cowrote, directed, and starred at 25

years of age in what many consider the greatest movie ever

made, Citizen Kane (1941). Welles completed the direction of

a mere dozen feature films during the length of his career,

plus five other assorted full-length movies that were either

never finished or for which he did not receive directorial

credit. Several of his subsequent movies were brilliant; others

were flawed and oftentimes poorly made from a technical

standpoint, but they were never boring. Critic Andrew Sarris

wrote, “the dramatic conflict in a Welles film often arises from

the dialectical collision between morality and megalomania,

and Welles more often than not plays the megalomanical vil-

lain without stilling the calls of conscience.” Welles not only

proved to be a powerful performer in his own movies but a

visual and aural force (he had a marvelous, deep, resonant

voice) in the films of many other directors, as well.

Born to a rich Wisconsin couple, he was an enormously

gifted child who, among other astonishing accomplishments,

read Shakespeare as a virtual tot. His youth, however, was

beset by tragedy; his mother died when he was eight years

old, and four years later, Welles’s father died. Dr. Maurice

Bernstein, a physician friend of the family, became Welles’s

guardian, and his memory later figured prominently in Citi-

zen Kane, split between the harsh banker/guardian of the

young Charles Foster Kane and the sweet-tempered man

(named Bernstein) who later ran Kane’s newspapers.

Welles never attended college. He was besieged with

scholarship offers but, instead, set off for Ireland to sketch.

While on the Emerald Isle, he bluffed his way into an acting

career by pretending to be a famous New York theater star

and made his professional debut in a leading role on the stage

of the renowned Gate Theater. He drew excellent reviews

and planned to continue his acting career but had little suc-

cess in winning roles in either London or New York. Unper-

turbed, the young genius continued to travel and did the

usual expatriate activities, including fighting bulls in Spain.

After returning to America, Welles tried the theater again,

this time making his way to Broadway in the role of Tybalt in

the 1934 production of Romeo and Juliet. In that same year he

married actress Virginia Nicholson (divorced 1939), and had

his first brush with moviemaking, codirecting and appearing

in a four-minute short entitled The Hearts of Age.

During the rest of the 1930s, Welles was a cyclone of

activity, performing on radio, collaborating with John

Houseman as coproducer and director of the Phoenix The-

ater Group, the Federal Theater Project, and their most

famous theatrical enterprise, the brash and innovative Mer-

cury Theater, which they founded. The Mercury Theater

quickly gained a reputation for excellence that led Welles and

Houseman to create a radio show called The Mercury Theater

on the Air, which was responsible for the stunning 1938 Hal-

loween broadcast of H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds. The

program offered fake news reports of a Martian invasion,

which a surprisingly large segment of the population took to

be the truth, causing widespread panic. Welles directed the

program and played the leading character.

In Hollywood, the struggling RKO studio was in des-

perate need of new ideas, new talent, and especially some

inexpensively produced big hits. They saw Welles as a hot

radio and theatrical personality with a penchant for splashy

showmanship. He was, to their point of view, exactly what

they needed. The studio gave him carte blanche to make a

film with complete artistic control just so long as he stayed

within a rather severe budget. After several false starts on

other projects, Welles settled on Citizen Kane, a thinly veiled

biography of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst

WELLES, ORSON

455

but also (and unrecognized at the time) a somewhat autobi-

ographical story as well. Hearst’s attempts at stopping the

distribution of the film failed, and it was released to critical

raves and, contrary to popular mythology, to respectable box

office—though the film was hardly the huge success RKO

had hoped it would be. However, Citizen Kane was certainly

recognized by the Hollywood establishment as a superb

piece of filmmaking and honored with nine Oscar nomina-

tions, including most of the major awards, such as Best Film,

Best Director, Best Actor (Welles), and Best Photography. It

won but one Oscar, for Best Original Screenplay, which

Welles shared with Herman J. Mankiewicz.

Citizen Kane represented a huge leap forward in filmmak-

ing, both in its style and in its subject matter. In style, it was

a harbinger of the

FILM NOIR

movement with its dark, fore-

boding use of shadows and oppressive low-angle shots. The

deep-focus cinematography of Gregg Toland was never used

to better effect, hastening its adoption by other filmmakers.

In addition, Welles’s radio knowledge brought clever innova-

tions to the use of sound in Citizen Kane. The movie’s

baroque tale of lost innocence ushered in a new maturity in

the subject matter of Hollywood movies, which would later

be hastened by the events of World War II. Finally, the struc-

ture of the film itself, its clever telling of the story from sev-

eral different viewpoints, forever after opened up the narra-

tive possibilities of moviemaking.

Welles’s brilliance was not appreciated by RKO. The final

print of his second film, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), was

drastically cut in his absence while he was away making a film

for RKO in South America (which never saw the light of day).

The Magnificent Ambersons was dismissed by both the critics and

the public but was later reassessed as a massacred masterpiece.

After handing over the directorial reins to Norman Foster

for his thriller Journey into Fear (1943), Welles didn’t get a

chance to direct again until he made The Stranger (1946) with

the understanding that he would not deviate from the script. It

was a rather conventional suspense film to which Welles

brought his flair as director and actor. The commercial success

of that film led to his opportunity to write and direct The Lady

from Shanghai (1948), starring his second wife, Rita Hayworth

(wed 1943, divorced 1947). The film is best remembered for

its clever climax in which the characters have a shoot-out in a

hall of mirrors, shattering their multiple images. Despite the

nifty finale, the movie was a box-office failure.

Welles went on to make movies on the cheap, receiving

little acclaim for his work and even less commercial success.

To finance many of his films, he acted in most anything that

came along, often improving the movies he appeared in by

his mere presence. Among his directorial efforts during the

1940s and 1950s were Macbeth (1948), Othello (1952), Mr.

Arkadin (1955, also known as Confidential Report), and the

low-budget gem Touch of Evil (1958), which many consider

among Welles’s best films after Citizen Kane. But not even

Touch of Evil could revive his directorial career, despite its

being hailed as a masterpiece in Europe.

Welles spent much of his time where he was most appre-

ciated, living and working in Europe. He made only a hand-

ful of other films, all of them overseas: the disappointing The

Trial (1962), the much-admired Chimes at Midnight (1966),

the sweetly sensuous The Immortal Story (1968), and the

intriguing semidocumentary F for Fake (1973). Welles also

spent a great deal of time on a number of unfinished projects,

among them a version of Don Quixote that he began in 1955

and worked on intermittently until many of his cast members

died; The Deep; and The Other Side of the Wind.

Meanwhile, as an actor, he added his considerable pres-

ence to such films as Jane Eyre (1944), The Third Man (1949),

Moby Dick (1956), Compulsion (1959), A Man for All Seasons

(1956), Catch-22 (1970), Voyage of the Damned (1976), Butterfly

(1982), and dozens of others, most of them made in Europe.

In 1975, Welles received the American Film Institute’s

Life Achievement Award, an honor richly deserved. He later

settled in Las Vegas and became a frequent TV talk show

guest and pitchman for several commercial products. He

seemed to enjoy his rekindled celebrity and acceptance in the

show business mainstream, despite the fact that he still could

not receive funding to direct motion pictures.

Welles died of a heart attack in his home in Las Vegas.

See also

CITIZEN KANE

;

HAYWORTH

,

RITA

;

HERRMANN

,

BERNARD

;

HESTON

,

CHARLTON

;

HOUSEMAN

,

JOHN

;

MANKIEWICZ

,

HERMAN J

.;

TOLAND

,

GREGG

.

WELLES, ORSON

456

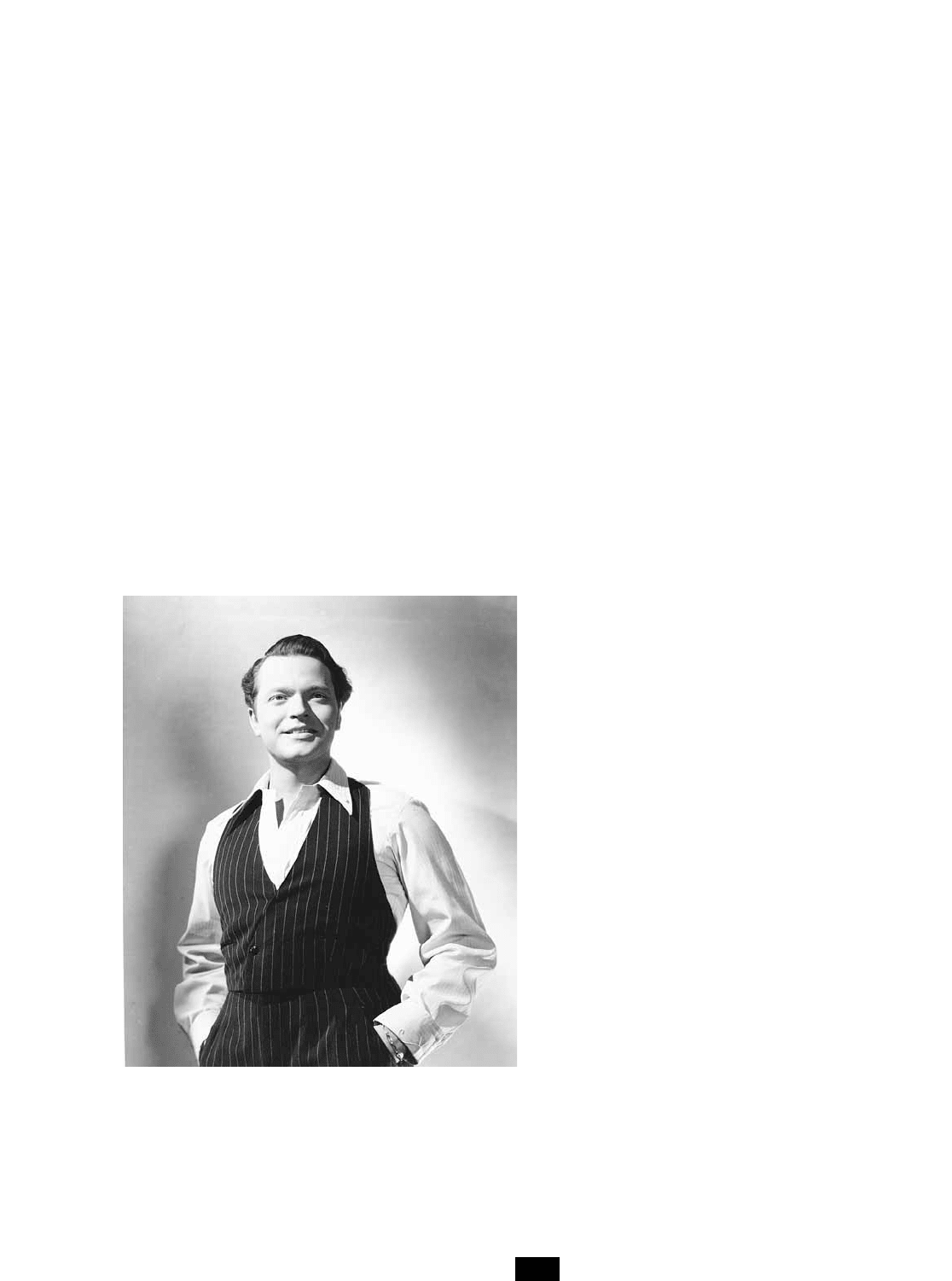

No one had a more auspicious beginning in the movie

business than Orson Welles. Seen here in a publicity still

for his first film, Citizen Kane (1941), he cowrote, directed,

and starred in that masterpiece, though he never fully

duplicated his initial success.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF

THE SIEGEL COLLECTION)

Wellman, William A. (1896–1975) A director of 76

movies, a number of them Hollywood milestones. He was

known within the film industry as “Wild Bill” Wellman due to

his gallant war record, as well as his hot temper and hard

drinking. He was, nonetheless, a competent filmmaker who

was nominated three times for Best Director Academy

Awards, for A Star Is Born (1937), Battleground (1949), and The

High and the Mighty (1954). He never took the Oscar home.

William Augustus Wellman was born for excitement. A

high school drop-out from Brookline, Massachusetts, he

played minor league hockey before joining the French For-

eign Legion as an ambulance driver during the First World

War. Later in the conflict, he became a pilot in the famous

Lafayette Escadrille and served with distinction, winning the

Croix de Guerre. Life after the war was, at first, a good deal

less exciting. He worked as a salesman but soon gave that up

to become a wing-walker in an air circus.

Wellman’s entry into the movie business was typically

dramatic. Forced to make an emergency landing, he brought

his plane down on the grounds of

DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS

’s

estate. Fairbanks, ever the cheerful and friendly sort, offered

Wellman a job as an actor in his 1919 film Knickerbocker

Buckaroo. Once in the business, however, Wellman decided to

tinker with the machinery of filmmaking rather than hone his

acting skills. During the next four years, he worked as a prop-

erty man and an assistant director before making his directo-

rial debut with The Man Who Won (1923).

A strong-willed man, he quickly moved from directing

low-budget westerns to more important features. By the end of

the silent era, he was considered a major talent, especially

when he made what became the first Academy Award-winning

Best Picture, Wings (1927), a film famous for its incredible fly-

ing sequences. Drawing on his wartime experiences, the direc-

tor poured his heart and soul into the film’s aerial combat

footage and turned the movie into a blockbuster hit.

By and large, war movies and male action/adventure films

proved to be Wellman’s forte. Among his better efforts in the

genres were The Public Enemy (1931), which became a gang-

ster classic, Heroes for Sale (1933), Call of the Wild (1935), Beau

Geste (1939), which benefited from Wellman’s firsthand expe-

rience as a Legionnaire, and The Story of G.I. Joe (1945).

Wellman never had a particularly light touch with romance,

but he was a capable director of hard-edged comedies, proving

his worth with such films as Nothing Sacred (1937) and Roxie

Hart (1942). Surprisingly (given his own hard-boiled approach

to life), he made several films with a social conscience, such as

Wild Boys of the Road (1933) and The Ox-Bow Incident (1943).

These films, however, may owe more to their writers and pro-

ducers than to Wellman’s own interest in the subject matter.

His last movie was Lafayette Escadrille (1958), a film obvi-

ously made from the heart; he wrote the script himself, but

it was sadly unconvincing. When he died of leukemia at the

age of 79, the old flying ace left instructions that he be cre-

mated and his ashes scattered to the four winds from a high-

flying airplane.

In the end, Wellman was not so much a stylist or an artist

as a man who saw excitement in the movie business and

jumped on board for the ride.

West, Mae (1892–1980) Looking more like a female

impersonator than a sex symbol, she was easily the greatest

comedienne in film history. With a combination of outra-

geous hip swinging and outlandish double entendres, she

both shocked and delighted audiences with her comically

sexy sensibility. Her persona was well crafted from the very

beginning because Mae West created it herself. In her most

famous films, she not only starred but also wrote her own

scripts—or, at the very least, her own dialogue.

The daughter of a prominent heavyweight prize-fighter,

West was brought up in the public eye and she clearly reveled

in it. At the age of six, she was appearing in stock in her

hometown: Brooklyn, New York. After that, she went into

vaudeville, billed as “The Baby Vamp,” eventually becoming

the originator of the shimmy dance.

In 1926, West starred on Broadway in a play she had writ-

ten, produced, and directed. It was titled Sex, and it caused an

uproar. People either clamored for tickets or clamored for

West to be thrown in jail for public indecency. In the end, the

latter group won out; the impressario and star was thrown in

jail for 10 days on an obscenity charge.

But her imprisonment was the best publicity West could

have hoped for. After two less-successful ventures, she

opened on Broadway in 1928 with a huge hit, Diamond Lil.

Two more plays followed—one of which brought her back to

court on obscenity charges, but this time she beat the rap.

In the early 1930s, with the depression in full swing, Hol-

lywood studios were willing to try anything to get people into

their theaters. One of the more desperate studios was Para-

mount. George Raft wanted Mae West for his film Night

After Night (1932), and the studio decided to hire her as a

supporting player. She refused the part, however, until she

was allowed to write her own dialogue.

Paramount never regretted granting her request. West

became a film star the moment she hit the screen when she

returned a hat-check girl’s exclamation of “Goodness, what

beautiful diamonds,” with the riposte “Goodness had nothing

to do with it, dearie.” Many years later George Raft wrote, “In

this picture, Mae West stole everything but the cameras.”

Her next film was based on her play Diamond Lil, though

Paramount changed the title because of the show’s salacious

reputation. Calling the film She Done Him Wrong (1933), the

studio billed West as the star. The movie was a major hit, as

was her next vehicle, I’m No Angel (1933). The latter film

brought $3 million into Paramount’s coffers, making it one of

the biggest hits of the year. Both costarred

CARY GRANT

.

It was partly due to West’s notoriety that the Hays Office

strengthened its production code. (See

THE HAYS CODE

.) As a

result, her next movie, originally titled It Ain’t No Sin, was

given the more innocuous name Belle of the Nineties (1934), but

West was more clever than her keepers, and despite censor-

required script changes, her double entendres still elicited

shocked laughter from her fans.

By 1935, with three hit movies in a row, Mae West

became the highest paid woman in America. After a modest

success that same year with Goin’ to Town, she scored another

hit with Klondike Annie (1936). But it was generally downhill

from that point on, both in film content and in audience

WEST, MAE

457