Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Bathgate, a prestigious picture adapted by Tom Stoppard

from the E. L. Doctorow novel.

Other prestigious projects included

ROBERT ALTMAN

’s The

Player (1992) and a memorable role in

QUENTIN TARANTINO

’s

Pulp Fiction (1994). Drawn to the offbeat, he starred in Luc

Besson’s The Fifth Element (1997), Terry Gilliam’s Twelve Mon-

keys (1995, a remake of Chris Marker’s La Jetée), and Last Man

Standing (1997, a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Japanese classic,

Yojimbo). Willis also appeared in The Jackal (1997), Armageddon

(1998), the hit The Sixth Sense (1999), The Whole Nine Yards

(2000), Unbreakable (2000), and Tears of the Sun (2003).

Willis, Gordon (1931– ) A gifted cinematographer

who has rediscovered the beauty of black-and-white photog-

raphy under the direction of

WOODY ALLEN

. Willis, who

began his career in 1970, has consistently worked with Allen

since Annie Hall (1977), but even before their unique collab-

oration, the cinematographer had firmly established a dis-

tinctive atmospheric style in films such as Loving (1970),

Klute (1971), and, most notably, The Godfather (1972) and The

Godfather, Part II (1974).

Working with Woody Allen, however, Willis has received

his overdue recognition. In particular, his evocative black-

and-white photography for films such as Interiors (1978),

Manhattan (1979), Zelig (1983), for which he won an Oscar

nomination, and Broadway Danny Rose (1984) has highlighted

a nearly lost art. He was nominated for an Academy Award

for Best Cinematography for his work on The Godfather, Part

III (1990) and was featured in the documentary Visions of

Light: The Art of Cinematography (1992). He received the

Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of

Cinematographers, a fitting tribute to one of Hollywood’s

most gifted cinematographers.

Wise, Robert (1914– ) A former film editor turned

director and sometime producer who has quietly emerged as

a filmmaker of considerable stature. It is no coincidence that

Wise’s career overlaps with many of Hollywood’s finest

moments. He edited

ORSON WELLES

’s two classics, Citizen

Kane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), directed

three films in the highly praised

VAL LEWTON

series of hor-

ror movies in the early 1940s, directed several low-budget

genre films in the late 1940s and early 1950s that have

become cult classics, and then directed several of Holly-

wood’s most expensive musicals of the 1960s, including two

monster hits. In all, Wise’s pictures have garnered 67 Acad-

emy Award nominations and 19 Oscars. Wise himself has

been nominated seven times and has won four Oscars. He

was also the recipient of the academy’s Irving Thalberg

Award in 1967 and the Directors Guild prestigious

D

.

W

.

GRIFFITH

Award in 1988.

The son of a meat packer, Wise had hoped to become a

journalist but was unable to continue his studies during the

depression. Looking for work, he traveled to Hollywood,

where he got a job as a messenger in RKO’s film editing

department with the help of his older brother, David, then an

accountant with the studio. Soon he was fascinated by the

way movies were cut and patched together, and before long

he was given an opportunity to try his hand at the art. After

nine months, he was made an apprentice sound-effects editor

and later a music editor.

Wise received his first film credit for a 10-minute short

subject and eventually received a promotion to assistant edi-

tor, finally becoming a film editor in 1938. He edited such

films as Bachelor Mother (1939), The Hunchback of Notre Dame

(1939), The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939), and The

Fallen Sparrow (1943). In addition to editing the previously

mentioned Welles films, he also directed the controversial

final scenes in The Magnificent Ambersons, much to the con-

sternation of Welles’s devotees.

After the Ambersons experience, Wise began to bombard

RKO executives with requests to direct. In 1943, he was edit-

ing Curse of the Cat People when its original director, far

behind schedule, was removed. Wise was given the job; the

movie became a hit in the Val Lewton cycle of horror films;

and Wise was established forevermore as a director.

During the next several years, he continued to direct low-

budget films, many of them horror and suspense movies such

as the highly regarded The Body Snatcher (1945) and Born to

Kill (1947). His big break came with Blood on the Moon (1948),

a significant critical and commercial success. He followed it

WISE, ROBERT

467

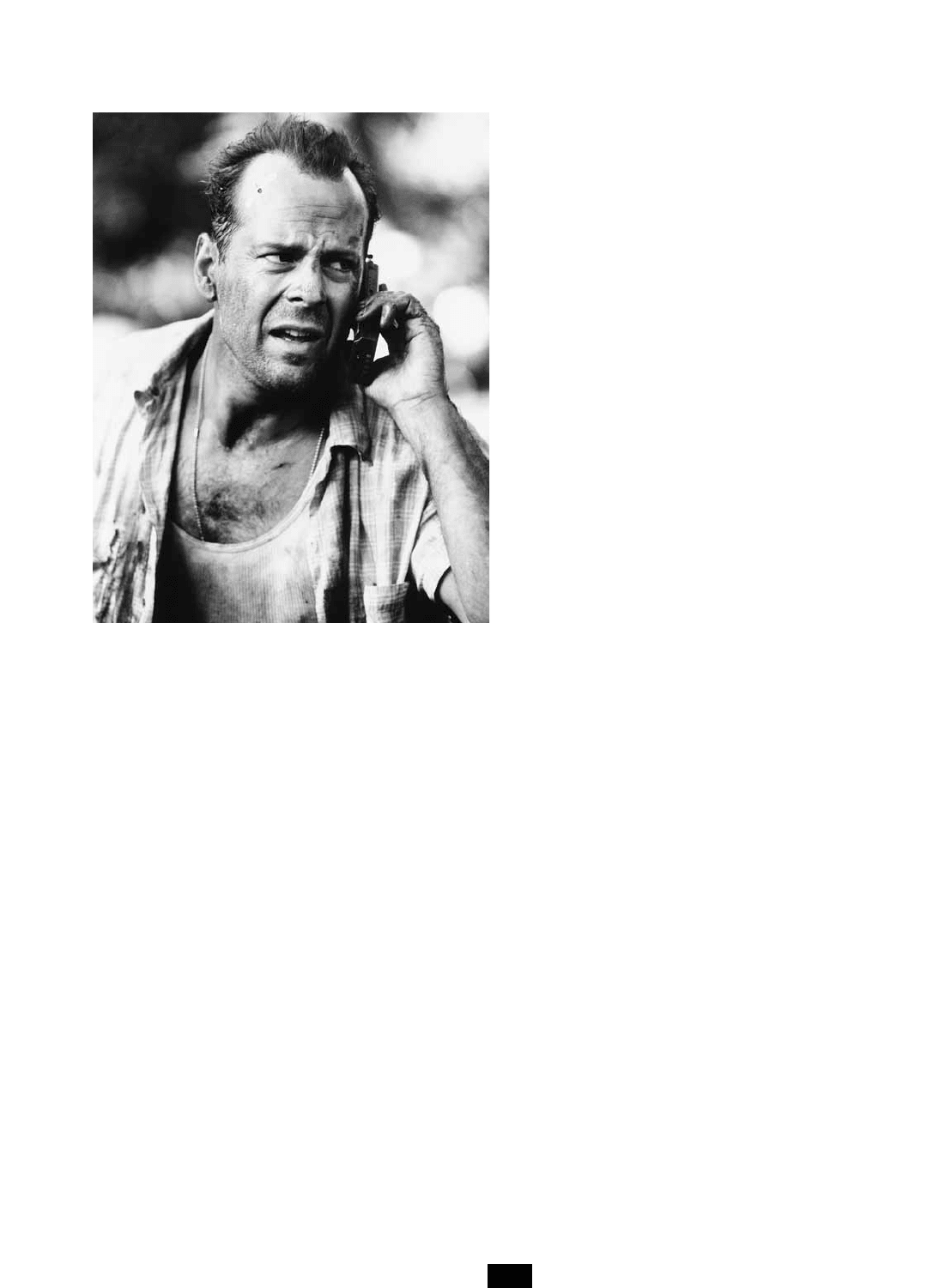

Bruce Willis in Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995) (PHOTO

COURTESY TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX)

with what some film buffs consider one the best boxing

movies ever made (and also one of very few movies that takes

place in real time), The Set-Up (1949). Not long after, in

1951, Wise made yet another cult favorite, the memorable

science-fiction film The Day the Earth Stood Still.

Wise’s films became less interesting during the rest of the

1950s, but he made a few solid hits, among them Executive

Suite (1954), Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), Run Silent,

Run Deep (1958), and I Want to Live! (1958). It wasn’t until the

early 1960s, however, that Wise ascended the Hollywood lad-

der as a director of megabuck hits, producing and codirecting

(with Jerome Robbins) West Side Story (1961) and directing

and producing The Sound of Music (1965). Wise won double

Oscars for both films, garnering

ACADEMY AWARDS

for Best

Director and producer of those two Best Picture winners.

As one of the grand old men of Hollywood and one of the

few directors the studios would entrust with a big budget,

Wise continued to make expensive movies. Except for The

Sand Pebbles (1966), he had more misses than hits, making

such major bombs as Star! (1968) and The Hindenburg (1975).

Nonetheless, the old pro who had directed The Day the Earth

Stood Still was brought in to direct the first of what would

become a hit series of science fiction films, Star Trek—The

Motion Picture (1979).

Wise has been less active as a director in recent years, hav-

ing been elected president of the Academy of Motion Picture

Arts and Sciences in 1985. He did, however, finally return to

film directing in 1989 with the disappointing musical Rooftops.

women directors For all the glamour and beauty that is

Hollywood, men have dominated the movie industry for

most of its existence, but if in recent years it seems as if

women have been making inroads as writers, producers, and,

particularly, directors, female success in the motion picture

business doesn’t begin to touch the influence women had in

the industry during the silent era.

A great many women pioneered the movies alongside

men in the years before the formation of the studio system.

Alice Guy Blaché was the world’s first woman director,

beginning her work in France in 1896. In 1910, she became

the first woman to own her own studio in the United States,

the Solax Company. A number of other women would later

have their own studios and production companies, including

Lule Warrenton, Dorothy Davenport, and Lois Weber.

The women directors of the 1910s and 1920s weren’t

unusual, nor were they relegated to minor movie status.

According to Anthony Slide, in his book Early Women Direc-

tors, most film studios employed at least one female director,

and Universal Pictures actually had, at one time, nine women

in charge of their own productions.

A significant number of actresses became directors during

the silent era, usually starting their careers behind the cam-

era by directing themselves. Among the less well-remem-

bered actress/directors were Cleo Madison, Ruth

Stonehouse, Margery Wilson, Gene Gauntier, Kathlyn

Williams, and Lucille McVey. Among the more famous stars

who directed themselves were

LILLIAN GISH

, Alla Nazimova,

and Mabel Normand.

Women were also well represented in the ranks of sce-

nario writers. Many of these screenwriters became directors,

as well. For instance, Ida May Park, Ruth Ann Baldwin, and

Jeanie MacPherson were all scenario writers who became

directors. The most successful of all female screenwriters,

Frances Marion, who wrote a prodigious number of hit films,

including Stella Dallas (1925), The Champ (1931), Dinner at

Eight (1933), and Camille (1937), also directed and produced

several films. She did not, however, have the same success as

a director as she had as a screenwriter.

By the time of the talkie revolution, women were finding

it increasingly difficult to find work as directors. The only

woman who managed to make it into the 1930s as a director

at a major studio was Dorothy Arzner; she was Hollywood’s

only woman director at that time. Among her credits were

such films as Christopher Strong (1933) and Craig’s Wife (1936).

There was no other female director at a major studio in

Hollywood until actress Ida Lupino began to work behind

the camera in 1950 with Outrage, which she also coscripted.

She directed a handful of other motion pictures, leaving the

door open for other women to follow.

The flow of female film directors continued as a trickle

with Joan Micklin Silver’s much-admired movie Hester Street

(1975). Silver went on to direct the popular romantic comedy

Crossing Delancey (1988); the well-received and controversial

A Private Matter (1992), a film about abortion; and two other

films, one made for cable and one a disappointing teen flick.

Claudia Weill directed Girlfriends in 1978, but it was not until

1997 that she got to direct another film, Critical Choices, a film

about struggles at an abortion clinic.

WOMEN DIRECTORS

468

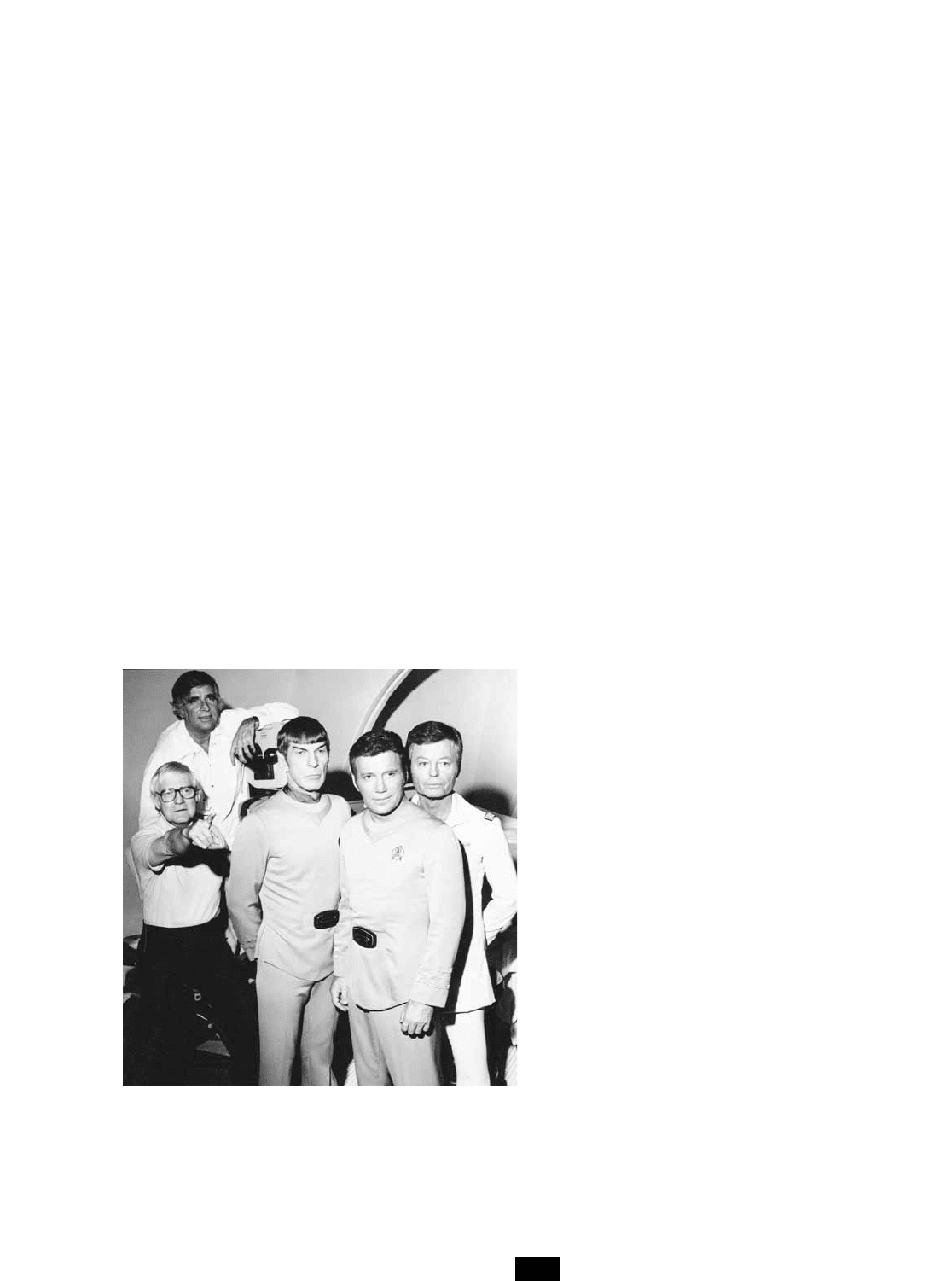

Director Robert Wise’s pictures have garnered numerous

Academy Award nominations and Oscars. Wise himself has

been nominated several times and has won several Oscars.

He is pictured here directing Star Trek—The Motion Picture

(1979)

(PHOTO © 1978 PARAMOUNT PICTURES CORPO-

RATION, COURTESY OF ROBERT WISE)

In the late 1970s, some actresses stepped behind the cam-

era. Anne Bancroft coscripted and directed Fatso (1979), and

Barbra Streisand began her directing career with Yentl (1983),

which she followed by the critically acclaimed and popular

The Prince of Tides (1991) and The Mirror Has Two Faces (1996).

Sondra Locke directed and starred in Ratboy (1986), which

was followed by Impulse (1990) and Trading Favors (1997).

Diane Keaton broke into directing in 1987 with Heaven,

which was followed by Wildflower (1991) and Unsung Heroes

(1995). Lee Grant directed two films, Tell Me a Riddle (1980)

and Staying Together (1989). The most successful of the

actress/directors has been

PENNY MARSHALL

of Laverne and

Shirley television fame. She began with the hugely popular Big

(1988), starring Tom Hanks, and has continued to make excel-

lent films such as Awakenings (1990), which won an Oscar

nomination for Best Picture; A League of Their Own (1992), a

film about women’s baseball; Renaissance Man (1994), a com-

edy with Danny DeVito; and The Preacher’s Wife (1996), with

DENZEL WASHINGTON

and Whitney Houston.

More significantly, nonactresses have recently been mak-

ing their mark in Hollywood as directors. Susan Seidelman

directed four films in the 1980s, among them the cult classic

Desperately Seeking Susan (1985), but her only film since then

is Tales of Erotica (1993). Joyce Chopra, Karen Arthur, and

Joan Tewksbury have also directed films in the 1990s. One of

the longest directing careers among women has been that of

Amy Heckerling, who got her start with the popular teen

flick Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) and has continued

to mine the teen and comic markets with such hits as Look

Who’s Talking (1989) and its 1990 sequel, as well as the

updated remake of Jane Austen’s Emma, titled Clueless (1995).

Two more prolific and outstanding female directors are

Martha Coolidge and Nora Ephron, who also writes scripts.

Coolidge’s hits include Rambling Rose (1991), Lost in Yonkers

(1993), and Out to Sea (1997). Ephron’s successes have been

even more impressive. She began with This Is My Life (1992),

which was followed by four films, including the two hugely

successful romantic comedies starring Meg Ryan and Tom

Hanks, Sleepless in Seattle (1993) and You’ve Got Mail (1998);

both received several Oscar nominations.

While there are still far fewer women behind movie cam-

eras than there are men, Hollywood is slowly working its way

back to the level of the silent era when women could be

found at all levels of filmmaking.

See also

ARZNER

,

DOROTHY

;

BLACHÉ

,

ALICE GUY

;

KEATON

,

DIANE

;

LUPINO

,

IDA

;

MARION

,

FRANCES

;

MAY

,

ELAINE

;

NORMAND

,

MABEL

;

STREISAND

,

BARBRA

.

women’s pictures Also sometimes known as tearjerkers

and “weepies,” these movies generally depict the romantic

(rather than the outright sexual) aspirations of leading char-

acters. Most often, the emotional rug is pulled from under

them by broken hearts, degradation, and illness. These films

always have a female protagonist and, unlike most serious

novels and stage works, are geared directly to the female

audience, often (at least in the past) with a decidedly senti-

mental point of view. Women’s pictures of the studio era are

notable for their great attention to clothing and hair styles, as

well as for their generally languid pace. Where films

designed for men often contain ample outdoor action scenes,

women’s pictures play themselves out on an internal land-

scape, marked by feelings, talk of commitments (or the lack

of them), betrayals, and so on, and as far as Hollywood is

concerned, they are also about big box office.

Films geared strictly to women became especially popu-

lar during the late 1910s and 1920s when going to the movies

became a solidly middle-class leisure activity. With his Victo-

rian sensibility,

D

.

W

.

GRIFFITH

made some of the most mem-

orable early women’s pictures. In Broken Blossoms (1919), for

instance, Lillian Gish falls in love with an Asian man (played

by Richard Barthelmess). Given the racial attitudes of the

time, it was an impossible love story, which made it a perfect

example of the genre’s developing formula. For decades to

come, any love affair that was doomed to failure had the

ingredients of a potential woman’s picture.

There have been any number of actresses who have

excelled in the genre, most notably

GRETA GARBO

, Janet

Gaynor, Irene Dunne,

VIVIEN LEIGH

, Margaret Sullavan,

BETTE DAVIS

,

JOAN CRAWFORD

, Greer Garson,

SUSAN HAY

-

WARD

,

SHIRLEY MACLAINE

, and many others. But when one

looks at the best of the women’s pictures, one sees the steady

work of a relative handful of directors. For example, it was

Clarence Brown who directed many of Greta Garbo’s most

romantic movies during the late 1920s and 1930s, and it was

Frank Borzage who made many of the greatest films of the

genre during those same years when he directed Seventh

Heaven (1927), Street Angel (1928), Bad Girl (1932), and History

Is Made at Night (1938). He was joined by

GEORGE CUKOR

who was well known for bringing out the best in female per-

formers and directed such fully realized women’s pictures as

Camille (1936), Gaslight (1944), and The Actress (1953). The last

director to genuinely specialize in the area (and then, only at

the end of his career), was

DOUGLAS SIRK

, who made such rich

soap operas as the remake of Magnificent Obsession (1954),

Written on the Wind (1957), and Tarnished Angels (1958).

The women’s picture thrived during the studio era, and

such films were often made by others besides the great mas-

ters of the genre. A good “schmaltzy” story was the key, and

both hack and accomplished directors contributed such clas-

sics as Back Street, which was so potent at the box office that

it was made three times, in 1932, 1941, and 1961. Waterloo

Bridge was another all-time great that was made three times,

in 1931, 1940, and in 1956 as Gaby. Leo McCarey made the

tearjerker Love Affair (1939) and decided to remake it himself

in 1957 as An Affair to Remember. Wuthering Heights (1939),

Random Harvest (1942), Letter from an Unknown Woman

(1948), Love Is a Many Splendored Thing (1955), and Splendor

in the Grass (1961) are a sampling of some of the genre’s best.

Perhaps the single most important woman’s picture from

an historical perspective was Dark Victory (1939). This

weepie starring Bette Davis was the first to have an essentially

innocent person die at the end. The commercial success of

Dark Victory opened the floodgates to a whole new era of

tearjerkers where life and death hang in the balance.

Women’s pictures went into decline once the studio era

ended and individual filmmakers, most of them men, began

to make movies independently. In addition, with the rise of

WOMEN’S PICTURES

469

the women’s movement, old-fashioned romance went some-

what out of style. Perhaps the last pure example of the genre

is Love Story (1970).

The modern women’s picture has become far more

sophisticated, but the basic elements of a female protagonist

and female concerns has not changed. Now, however, the

themes (in addition to romance and death) have been broad-

ened to include such social issues as career choice and rape.

Examples of the modern women’s picture are The Turning

Point (1977), Terms of Endearment (1983), The Accused (1988),

and Beaches (1989).

Because of changing attitudes toward sex and gender roles,

there have been relatively few “traditional” women’s films

since 1990. There is a kind of “unisex” quality about films,

except for the ultraviolent films men have traditionally liked.

The difference between the films still exists, however, as indi-

cated by the discussion of “women’s films” such as An Affair to

Remember (1957) and “men’s films” such as The Dirty Dozen

(1967) and in the film Sleepless in Seattle (1993). There are still

films that are more popular with women than with men.

Films dealing with the way women respond to each other

in the face of death include Marvin’s Room (1996) and One

True Thing (1998), both starring

MERYL STREEP

, who seems

to have an affinity for such roles. The “romance” films mostly

involved

MEG RYAN

and

JULIA ROBERTS

and included such

films as Sleepless in Seattle, You’ve Got Mail (1998), The Run-

away Bride (1999), and One Day in September (2000), the last

of which combines romance with death. A film about mature

romance was The Bridges of Madison County (1995), featuring

Meryl Streep and

CLINT EASTWOOD

. The most popular

romantic film of the 1990s was undoubtedly Titanic (1997), a

sentimental weepie that many adolescent girls bragged about

seeing more than a dozen times.

Of course, there is another side to romance—divorce—

and some films dealt with the problem seriously, but two

films approached the issue from a “women don’t get mad;

they get even” perspective. The First Wives Club (1996) fea-

tured the revenge exacted by Bette Midler,

DIANE KEATON

,

and

GOLDIE HAWN

; and Waiting to Exhale (1995) demon-

strated that black women were every bit as adept at taking

revenge as their white sisters.

Revenge was taken to new heights in Death and the

Maiden (1994) in which a woman (

SIGOURNEY WEAVER

)

avenges herself on the man whom she believes abused her 15

years before. The film was directed by

ROMAN POLANSKI

and

adapted from an Ariel Dorfman play. A similar film, also

adapted from a play, was Extremities (1986). The very fact

that these two plays were adapted to film indicates that their

makers believed there was an audience for them.

Other films that feature communities of women or mul-

tiple generations of women include Widows’ Peak (1994), a

film about a town run by women; Steel Magnolias (1989),

which focused on women in a beauty shop; Fried Green

Tomatoes (1991), a film about women gaining their inde-

pendence; Tea with Mussolini (1999), a film about women

“imprisoned” in Italy during World War II; and The Joy

Luck Club (1993), which traced the fates of Chinese-Ameri-

can women.

Two of the most critically acclaimed films of 2002 were

women’s films. The Hours was about three women in different

eras and asserted that independence is essential for women,

even if it means forsaking traditional spousal and child-rear-

ing duties. Far from Heaven explored the problems that beset

a 1950s suburban housewife who must deal not only with her

husband’s homosexuality but also with the bigotry of her

community when it discovers her association with an

African-American man.

See also

BORZAGE

,

FRANK

;

LE ROY

,

MERVYN

.

Wood, Natalie (1938–1981) She was among the rare

child actors who made the leap from moppet to adult movie

star, but she was an actress of contradictions. Though per-

ceived as a mediocre performer, she managed to garner three

Oscar nominations; though a great beauty, her acting lacked

a sensual fire; and despite her consistent popularity, she

never achieved superstar status and was often overshadowed

by her costars.

Born Natasha Gurdin to a Russian father and French

mother, she grew up speaking several languages and studied

dance (her mother had been a ballerina) at a very early age.

When she was four years old, Happy Land (1943) was being

filmed in her hometown of Rosita, California, and she landed

a tiny role in the movie. The director, Irving Pichel, was

impressed with her and cast her several years later when he

needed a child actress who could play the part of a German

refugee in Tomorrow Is Forever (1946). It was the start of the

actress’s career.

As a child star, Wood was no

MARGARET O

’

BRIEN

, but

she was both pretty and sincere. Young Natalie made her

mark in films such as Miracle on 34th Street (1947) and

Scudda-Hoo! Scudda-Hay! (1948). In the early 1950s she tried

television, starring in a series called Pride of the Family. She

did not succeed on the small screen and returned to the

movies, struggling through the awkward period of adoles-

cence. It wasn’t until she blossomed as a young adult and

costarred with

JAMES DEAN

in Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

that she emerged as a potential new star. Winning a Best

Supporting Actress Academy Award nomination for her per-

formance brought her increased visibility, though James

Dean was the focus of most people’s attention.

Full-fledged stardom did not come quickly. Just as she

was overwhelmed in Rebel Without a Cause by the acting of

James Dean and Sal Mineo, she passed through a succession

of 1950s films such as Marjorie Morningstar (1958) without

making a very great impression. Her films, though, were gen-

erally popular at the box office, and she was just 22 years old

as the 1960s began, a decade in which she gave the lion’s

share of her best and most memorable performances.

Her career finally took off when she starred opposite

WARREN BEATTY

in

ELIA KAZAN

’s production of Splendor in

the Grass (1961) and received an Oscar nomination for Best

Actress. To the surprise of many, she was then cast as Maria

in West Side Story (1961). Her childhood dance training came

in handy for the film, but her singing voice was dubbed by

Marni Nixon.

WOOD, NATALIE

470

Those two hit films were followed by a nearly unbroken

streak of box-office winners that lasted until the end of the

decade. She was at the height of her career, starring in Love

with the Proper Stranger (1963) with

STEVE MCQUEEN

and

winning her third and final Oscar nomination, Sex and the

Single Girl (1964) with

TONY CURTIS

, Inside Daisy Clover

(1966) with

ROBERT REDFORD

, This Property Is Condemned

(1966) with Redford again, and Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice

(1969) with Dyan Cannon, Elliott Gould, and Robert Culp.

The titles of most of her 1960s films were suggestive—

and often controversial—but both the movies and Natalie

Wood proved in the end to be rather tame.

Married twice to actor Robert Wagner, Ms. Wood

devoted most of the 1970s to home life. She made a few films

for TV and theatrical release, the most notable being the

underrated comedy with George Segal The Last Married Cou-

ple in America (1979). She nearly completed a big-budget

thriller called Brainstorm when she drowned in a mysterious

boating accident in 1981. Brainstorm was released posthu-

mously in 1983 with little fanfare.

See also

CHILD STARS

.

Woodward, Joanne (1930– ) An actress who began

her film career in sexy roles but who soon displayed her tal-

ent starring in character parts to which she brought depth of

perception. Since her film career began in 1955, Woodward

has either acted with or been directed by her longtime hus-

band, Paul Newman, in nearly half of all her motion pictures.

This was not a case of nepotism, however; Woodward had

already won an Oscar for her electric performance in The

Three Faces of Eve (1957) during Newman’s initial flush of

popularity in the mid- to late 1950s.

Born to a well-to-do family in Georgia, Woodward acted

in high school and college, as well as for a small community

theater, before making the trip to New York to study acting

at the Neighborhood Playhouse. Soon she began to appear in

live TV dramas, but had the first and most important break

of her career when she won an understudy role in the 1953

Broadway production of Picnic; the supporting-actor role in

the play was performed by Paul Newman. The two married

five years later in 1958.

Woodward made her movie debut in a starring role in

Count Three and Pray (1955). In the year that she and Newman

were wed, they starred together in two films, The Long Hot

Summer (1958) and Rally Round the Flag, Boys! (1958). Their

other acting collaborations include From the Terrace (1960),

Paris Blues (1961), A New Kind of Love (1963), Winning (1969),

WUSA (1970), and The Drowning Pool (1975). In most of the

later films, the couple was better than their material.

Woodward also starred in a number of films that were

directed by Newman: Rachel, Rachel (1968), for which she was

nominated for an Oscar, The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-

the-Moon Marigolds (1972), a TV movie The Shadow Box

(1981), Harry and Son (1984), in which Newman also starred,

and The Glass Menagerie (1987). These films were largely of a

very high caliber, although none of them was a box-office

winner except Rachel, Rachel, but in every film in which New-

man directed her, Woodward received glowing notices for

her work.

During the last 50 years, Woodward has done splendid

work in solo efforts that have often been overlooked. Her abil-

ities as a character actress are best displayed in movies such as

A Kiss before Dying (1956), The Sound and the Fury (1959), The

Stripper (1963), A Big Hand for the Little Lady (1966), A Fine

Madness (1966), and Summer Wishes, Winter Dreams (1973).

In addition to her film work, Woodward has been a com-

mitted stage actress and has also been active in making quality

TV movies, especially during the late 1970s and throughout

the 1980s. Along with her husband, she has also been a politi-

cal activist, lobbyist, and fund-raiser for liberal causes.

During the 1990s, Woodward did little acting, but what

work she did was improved by her presence. She provided the

voice of the narrator in

MARTIN SCORSESE

’s adaptation of

The Age of Innocence (1993), for example, anchoring that film

to the ethos of Edith Wharton’s New York during the 1870s.

Her most important role of the decade came in 1990, how-

ever, when she played Mrs. Bridge to Paul Newman’s Mr.

Bridge in the Merchant-Ivory adaptation of two novels by

Evan S. Connell, Mr. and Mrs. Bridge. She received the New

York Film Critics Best Actress Award and was nominated for

an Academy Award for this performance. Beyond this,

Woodward was featured in three made-for-television films—

Foreign Affairs and Blind Spot (both 1993) and Breathing

Lessons (1994)—and she also took a supporting role in

Philadelphia, directed by Jonathan Demme in 1993.

See also

NEWMAN

,

PAUL

.

writer-directors The identity of the person most

responsible for a motion picture has been hotly debated. In

one camp, it is argued that the screenwriter’s original charac-

ters, plot, and themes are the core of what is seen on the big

screen. The other camp holds that the director is the ultimate

creator of a film because he or she controls all of its elements,

choosing the locations and the actors, deciding on the light-

ing and music, among many other things. Both make cogent

points, but there can be no argument that those filmmakers

who both write and direct their films are the ultimate cre-

ators, devisers, and realizers of their stories. Surprisingly,

however, relatively few writer-directors have prospered in

Hollywood, no doubt because it is hard enough to succeed in

one of these areas, let alone both. Since the early 1940s,

though, there has been an increasing number of writer-direc-

tors who have not only made their mark in American films

but have also changed the course of movie history.

Scripts were often unnecessary during the early silent era,

but as films became more complex, writers were hired to organ-

ize and structure their plots as well as write title cards. Thomas

H. Ince was probably the first important writer-director. He

wrote detailed notes before filming, both for himself and later

for other directors whom he supervised. There were relatively

few writer-directors during the silent era, but the extravagant

Erich von Stroheim was a notable example. In the area of com-

edy,

CHARLIE CHAPLIN

and

BUSTER KEATON

were predomi-

nant writer-directors, who also starred in their own vehicles.

WRITER-DIRECTORS

471

The genuine flowering of the screenwriter’s craft, how-

ever, did not occur until the sound era. By then, the

STUDIO

SYSTEM

had already evolved, compartmentalizing the differ-

ent functions required to create a film (i.e., writers wrote,

directors directed, producers produced). During the 1930s,

the only significant attempt toward melding the jobs of writ-

ing and directing came when screenwriters Ben Hecht and

Charles MacArthur were given the chance to direct their own

films. The results were the wordy but fascinating Crime With-

out Passion (1934) and The Scoundrel (1935). Neither made any

impact at the box office, and in any event, the movies were

mostly directed by their cinematographer,

LEE GARMES

.

The rise of the writer-director began in earnest at Para-

mount in 1940 when the highly successful screenwriter Pre-

ston Sturges insisted on the right to direct his own work. He

struck a blow for creative control by succeeding handsomely

at the box office with seven consecutive comedy hits over a

five-year period.

Meanwhile, the struggling RKO studio, looking for a

shot in the arm, hired Orson Welles, who directed and

cowrote, as well as starred in, what many consider to be the

greatest movie ever made,

CITIZEN KANE

(1941).

At Warner Bros., John Huston had been writing success-

ful scripts, and he was promised that if his screenplay for

High Sierra (1940) was a hit, he’d be allowed to direct his own

film. It was, and he made his writer-director debut with The

Maltese Falcon (1941).

Not long after Sturges, Welles, and Huston broke the ice,

they were followed by Billy Wilder, who cowrote and

directed The Major and the Minor (1942). They remained the

big four throughout the 1940s and beyond.

The freedom of the writer-director has always been

bound by financial restrictions, especially when the purse

strings were held by conservative producers and studios.

Some writer-directors who came to prominence in the 1950s

and 1960s thrived under those conditions, among them

Richard Brooks and

BLAKE EDWARDS

. But many of the new

breed of writer-directors tended to work as independents,

most notably

SAMUEL FULLER

,

STANLEY KUBRICK

, and

JOHN CASSAVETES

.

In recent decades, writer-directors have become increas-

ingly commonplace as movies have become an accepted

mode of personal expression. The new wave of writer-

directors received its first big push in the area of screen com-

edy, thanks to the distinctive versions of Woody Allen and

Mel Brooks. The mammoth success of writer-director Fran-

cis Coppola’s The Godfather (1972) caused a trickle of such

filmmakers to turn into a flood. Successful screenwriters who

were anxious for the chance to direct their own films were

given funding, and such talents as John Milius, Paul

Schrader, and Lawrence Kasdan blossomed into critically

acclaimed moviemakers. Even Sylvester Stallone, much

maligned by critics as an actor, has proven himself a capable

writer-director on more than one occasion.

In the 1980s, a new crop of talented and commercially

viable writer-directors surfaced. For instance, John Sayles

emerged as an independent filmmaker who usually works out-

side the studio system making such intelligent and iconoclas-

tic films as Return of the Secaucus 7 (1980), The Brother from

Another Planet (1984), and Matewan (1987). Oliver Stone

became a mainstream writer-director with considerable box-

office clout, thanks to his Oscar-winning Platoon (1986) and

smash hit Wall Street (1987). Stone, however, has not suc-

cumbed to the lure of big box office; he followed his big-

budget, high-profile films with the scintillating art-circuit

winner Talk Radio (1989). Another newcomer to the writer-

director ranks has been playwright

DAVID MAMET

, who, after

writing scripts for films such as The Untouchables (1987), began

to direct his own screenplays, making such highly regarded

movies as House of Games (1987) and Things Change (1988).

Mamet’s latest projects (through 2003) were Homicide (1991),

The Spanish Prisoner (1997), The Winslow Boy (1999), State and

Main (2000), and Heist (2001).

Writer-director

M

.

NIGHT SHYAMALAN

emerged as a

powerful new filmmaker with The Sixth Sense (1999), a tale of

the supernatural starring

BRUCE WILLIS

and Haley Joel

Osment. The movie turned out to be a surprise hit. Shya-

malan followed with Unbreakable (2000), an underrated

movie that didn’t fare well at the box office despite the pres-

ence of Bruce Willis and

SAMUEL L

.

JACKSON

. He returned

with the science-fiction movie Signs (2002), starring

MEL

GIBSON

, another hit that proved he could continue to deliver

thoughtful, well-crafted movies.

See also

ALLEN

,

WOODY

;

BROOKS

,

MEL

;

BROOKS

,

RICHARD

;

COPPOLA

,

FRANCIS FORD

;

HECHT

,

BEN

;

HUSTON

,

JOHN

;

INCE

,

THOMAS H

.;

LEVINSON

,

BARRY

;

MILIUS

,

JOHN

;

SAYLES

,

JOHN

;

SCHRADER

,

PAUL

;

STALLONE

,

SYLVESTER

;

STROHEIM

,

ERICH VON

;

STURGES

,

PRESTON

;

WELLES

,

ORSON

;

WILDER

,

BILLY

.

Wyler, William (1902–1981) In a career spanning 45

years, he directed nearly 50 features. During his long and

fruitful association with independent producer

SAMUEL

GOLDWYN

, Wyler became a director of prestige projects that

were often adaptations of stage plays, many of them by the

leading playwrights of his era. In an effort to remain true to

the spatial relations of the plays he filmed, Wyler pioneered

the use of deep-focus photography with the help of his cine-

WYLER, WILLIAM

472

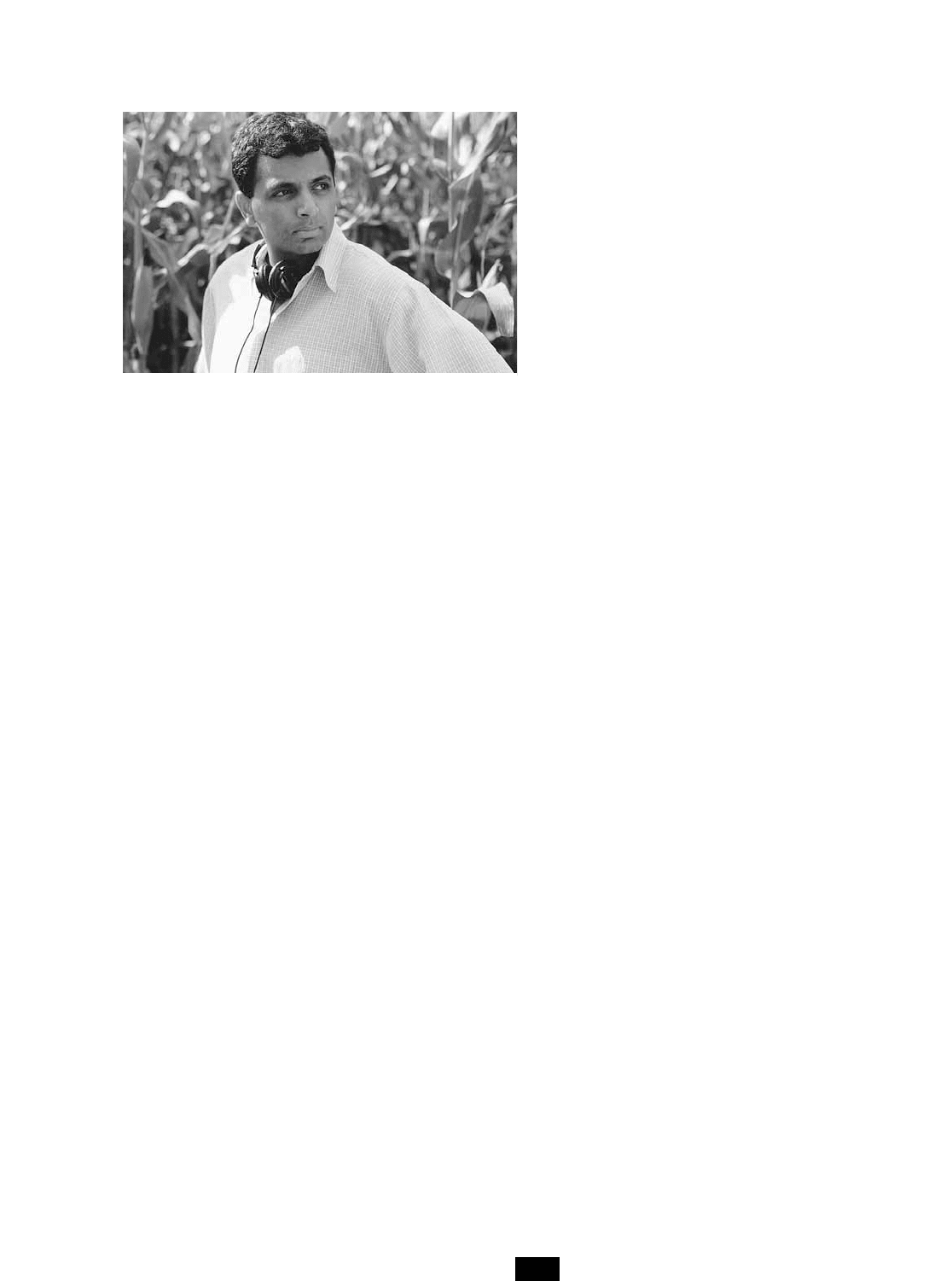

Writer-director M. Night Shyamalan (AUTHOR’S

COLLECTION)

matographer,

GREGG TOLAND

. Wyler’s films were popular

and highly respected efforts that brought him a record 12

Best Director Academy Award nominations; he won the

Oscar on three occasions. In 1965, he became one of the very

few directors to be honored with the prestigious Irving G.

Thalberg Memorial Award. He followed that with the Amer-

ican Film Institute Life Achievement Award in 1976.

Born to a Swiss family in Mulhouse, Alsace, when it was

German territory, he was educated on two fronts, business

and the arts. His entry into films was a result of the legendary

nepotism of

CARL LAEMMLE

, who hired hundreds of relatives

and put them to work at his burgeoning movie company,

Universal Pictures. Wyler was related to Laemmle ever so

distantly through his mother, but the American movie mogul

happily engaged the young man in 1922 as a publicity writer

in his movie company’s New York office.

Soon after arriving in America, however, Wyler was dis-

patched to Hollywood, where, in quick succession, he held a

variety of jobs, including grip, prop master, casting director,

production assistant, and assistant director. Wyler learned

the business of moviemaking quickly and was given the

opportunity to direct when he was just 23 years old. In addi-

tion to directing dozens of two-reel westerns, he made his

feature film debut with Crook Busters (1925).

There was nothing terribly distinguished about his silent

films, though they were solidly made with good pacing and

plenty of action. In the early 1930s, however, he began to

direct issue-oriented stories that brought him critical notice,

among them Hell’s Heroes (1930), A House Divided (1932), and

Counsellor-at-Law (1933).

His career began to blossom more rapidly after he left

Universal in 1936 to begin his association with Samuel Gold-

wyn. Their first film together was an adaptation of Lillian

Hellman’s controversial play The Children’s Hour, which was

renamed in the 1936 film version, These Three. (Wyler

remade the film under the original title in 1962.)

Wyler went on to receive an unprecedented number of Best

Director Academy Award nominations. His 12 nominations

were for: the critically acclaimed Dodsworth (1936), the lushly

romantic Wuthering Heights (1939); the underrated Bette Davis

vehicle The Letter (1940), plus the overrated Bette Davis vehi-

cle The Little Foxes (1941); the hugely popular Mrs. Miniver

(1942) for which he also won the Oscar; the post-World War II

classic The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), which brought him his

second Oscar; the emotionally restrained The Heiress (1949);

the tough Detective Story (1951); the charming Roman Holiday

(1953); the warm family saga Friendly Persuasion (1956); the

big-budget megahit Ben-Hur (1959) for which he won his third

Oscar; and the idiosyncratic little movie The Collector (1965).

There is little thematic unity or consistency to Wyler’s

films, but their quality is constant. Nonetheless, auteurist

critics have criticized the director for never having exhibited

a consistent style or theme in his work. True or not, there has

hardly been a director who has made quite so many highly

regarded movies. Consider, for instance, that Wyler also

directed such memorable Hollywood milestones as Dead End

(1937), Jezebel (1938), The Westerner (1940), The Big Country

(1958), and Funny Girl (1968).

Though he is not often considered an actor’s director—

many performers openly hated him (he was notorious for

incessantly demanding retakes)—Wyler elicited 14 Oscar-

winning performances from his stars, not to mention a great

many Oscar-nominated performances, as well.

His last film was The Liberation of L. B. Jones (1970), after

which he retired.

Wyman, Jane (1914– ) An actress who made the

majority of her movies before attaining fame, Wyman has

appeared in more than 70 films in a career that began in

1936. She was cast as comic relief and tough blondes in

mostly unimportant movies during her early years in Holly-

wood but emerged a star thanks to the unexpected critical

and commercial success of The Lost Weekend (1945). The lat-

ter half of the 1940s and early 1950s were Wyman’s golden

years in Hollywood. She was nominated for four Best Actress

Oscars during that period, winning the Academy Award once

for her performance as the deaf-mute in Johnny Belinda

(1948). Today, Wyman is perhaps better known as both the

matriarch of the prime time TV soap Falcon Crest and as

RONALD REAGAN

’s first wife (1940–48).

Born Sarah Jane Fulks, she tried to break into the movies

as a child actress without success. Later, as a young adult, she

began to perform as a singer on radio, using the name Jane

Durrell. Still enamored of the movies, she finally began to

show up in films in minor roles, making her debut in Gold

Diggers of 1937 (1936). She went on to appear in an average

of more than six movies per year during the latter half of the

1930s, most of them of minor distinction. She did, however,

star along with Ronald Reagan in the popular Brother Rat

(1938), as well as its sequel, Brother Rat and a Baby (1940).

The two also costarred in An Angel from Texas (1940) and

Tugboat Annie Sails Again (1940).

After Reagan left Hollywood to join the war effort,

Wyman’s career began to pick up. Her strong performance

opposite Ray Milland’s Oscar-winning portrayal of an alco-

holic in The Lost Weekend was not overlooked by the industry.

Given better roles in “A” movies, she proved herself both a

versatile and a popular actress in The Yearling (1946) for

which she received her first Best Actress Academy Award

nomination; Magic Town (1947); the previously mentioned

Johnny Belinda; The Glass Menagerie (1950); The Blue Veil

(1951), which brought her another Oscar nomination; Mag-

nificent Obsession (1954), which got Wyman her fourth and

last Oscar bid; and All That Heaven Allows (1956).

Past her prime in the mid-1950s, Wyman turned to tele-

vision. Like actresses Donna Reed and

LORETTA YOUNG

, she

had her own program, The Jane Wyman Theater, which ran

from 1956 to 1960. She was little seen on movie screens both

during and after those years on the tube, appearing only in

Holiday for Lovers (1959), Pollyanna (1960), Bon Voyage!

(1962), and How to Commit Marriage (1969). She made her

unexpected comeback on television in 1981 when she joined

the original cast of the hit show Falcon Crest, in which she

starred as Angela Channing from 1981 until the series ended

in 1990.

WYMAN, JANE

473

Young, Loretta (1913–2000) An actress known within

the film industry as “Hollywood’s Beautiful Hack” because

she starred in so many mediocre movies. In a career that

began in earnest in 1927, Young appeared in more than 90

films, but most movie fans would be hard pressed to name

more than half a dozen of them. Yet she was personally mem-

orable due to her big doe eyes and high cheekbones; she was

truly one of Hollywood’s most striking beauties.

Born Gretchen Michaela Young, she was the product of a

broken home. Her mother gathered up her brood of daugh-

ters and went to Hollywood in the hope of getting the kids

into show business. Loretta was briefly a child actress in bit

roles before receiving a convent education. Later, when she

was 14, director Mervyn Le Roy called, wanting Loretta’s

older sister, Polly Ann, for a small role in Naughty but Nice

(1927). In Polly Ann’s absence, Loretta asked to play the role

instead, and Le Roy agreed.

Young had a sensitive, ethereal quality on film in her

youth, and she soon found plenty of work. Among her note-

worthy early films were Laugh Clown Laugh (1928) and The

Squall (1929), in which she proved herself capable as an

actress in sound films.

During the first half of the 1930s, she usually played lead-

ing roles in the movies of bigger stars; few pictures were built

around her. Nonetheless, she was effective in vehicles for stars

such as

JOHN BARRYMORE

in The Man from Blankleys (1930),

RONALD COLMAN

in The Devil to Pay (1930), Jean Harlow in

Platinum Blonde (1931), and

JAMES CAGNEY

in Taxi (1932).

474

Y

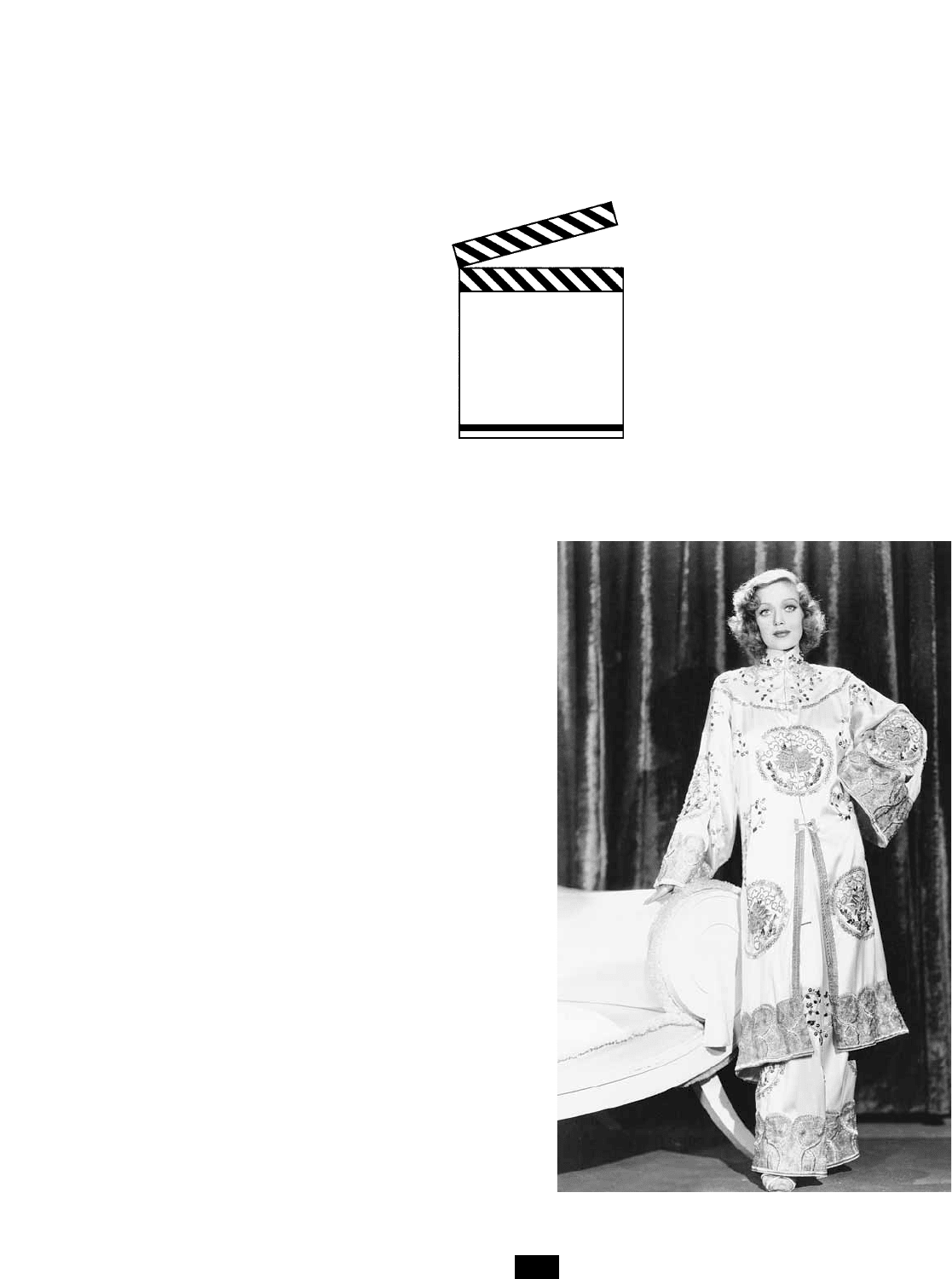

Loretta Young was a second-tier glamour queen who had

the nickname of “Hollywood’s Beautiful Hack.” Only late in

her movie career did she receive the kind of rich roles that

allowed her to show her talent.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF

THE SIEGEL COLLECTION)

By the mid-1930s, she became a star in her own right,

getting major roles in bigger-budget movies at her new stu-

dio,

TWENTIETH CENTURY

–

FOX

. She could be seen to fine

effect in such films as Ramona (1936), Ladies in Love (1936),

and Three Blind Mice (1938). Despite her star billing in “A”

movies, she was still mostly used for decoration and rarely

given meaty roles. Unhappy at Fox, she bitterly parted com-

pany with the studio.

Young’s career went into a minor tailspin during the early

1940s, and she appeared in many lesser productions,

although she shined as

ALAN LADD

’s love interest in China

(1943). By this time, she had been in the movies for more

than 15 years, and yet she was only in her early thirties. She

was far too beautiful and far too young to be washed up, and

she proved that she possessed both the skills and the drawing

power to reclaim her position as a top Hollywood star. She

rebounded in the latter half of the decade in films such as

Along Came Jones (1945) with

GARY COOPER

and the tightly

woven thriller The Stranger (1946), playing

ORSON WELLES

’s

wife (Welles also directed). But 1947 saw her at the pinnacle

of her Hollywood success, taking an Oscar home for her per-

formance in The Farmer’s Daughter. Unfortunately, her rise to

the top was short-lived. There were a couple of good films

thereafter, such as The Bishop’s Wife (1947), Come to the Stable

(1949), for which she was nominated for an Oscar, and Key to

the City (1950), but her subsequent movies were released as

“B’s,” including Half Angel (1952) and her last motion pic-

ture, It Happens Every Thursday (1953).

Seeing no future in the movie business, Young turned to

television and became the hostess and occasional star of The

Loretta Young Show (1953–61). It was a rousing success and a

multiple Emmy winner, thanks to her stunning wardrobe and

grande-dame style, not to mention some fine dramatic

moments. When the show went off the air, she resurfaced the

following year in The New Loretta Young Show, but the public

was no longer interested and it was soon cancelled. She lived

in quiet retirement afterward, making news only in 1972

when she sued and won a court case against NBC, which had

illegally aired her old TV series overseas.

Loretta Young’s last television appearance was in Lady in

a Corner (1989). The star of nearly 100 films died on August

12, 2000. A biography, Forever Young, by Joan Wester Ander-

son, revealed that Young’s “adopted” daughter, Judy, was in

fact the illegitimate child of Young and

CLARK GABLE

, whose

rumored liaison had been kept secret for fear that the scandal

would ruin both their Hollywood careers.

YOUNG, LORETTA

475

Zanuck, Darryl F. (1902–1979) A movie mogul who

was instrumental in the early growth of Warner Bros. and

who founded Twentieth Century–Fox, running the company

for a good part of its existence. Zanuck was a deeply involved

producer who personally supervised the creation of more

movies than any other head of production in Hollywood.

Although he was a mediocre, if prolific, screenwriter during

his early years in the movie industry, he always displayed a

great talent as an idea man who understood the requirements

of commercial storytelling.

Darryl Francis Zanuck was born in Wahoo, Nebraska,

but spent much of his youth in Los Angeles with his mother

and stepfather. He had his first encounter with the movies at

the age of seven, stumbling upon a film crew, who dressed

him up as a little Indian girl and put him in their movie, pay-

ing him a dollar a day.

Zanuck never bothered finishing high school. Instead, he

lied about his age and joined the army (he was one day shy of

his 15th birthday), seeing combat in France during World

War I. When he returned to America two years later, he

decided to become a writer. He collected more than his share

of rejections for his potboiler short stories until he finally

sold his first, Mad Desire, which was published in 1923. Other

sales followed, including a story bought by Fox and turned

into a film in 1923, the name of which has been lost.

To gain more prestige in the movie business, Zanuck

slapped together four of his scenarios and arranged to have

them published as a book; three of those stories were turned

into movies, and he was well on his way to becoming a regu-

lar contributor to the motion-picture business. After short

stints as a gag writer for

MACK SENNETT

,

HAROLD LLOYD

,

and

CHARLIE CHAPLIN

, Zanuck began to write for the then

struggling film company Warner Bros.

In 1924, he began to write scripts for Warners’ biggest

audience draw, the German shepherd Rin Tin Tin, and soon

proved to be a veritable volcano of story ideas. According to

Mel Gussow in his excellent biography of Zanuck, Don’t Say

Yes Until I Finish Talking, he wrote as many as 19 films in one

year. Finally, at the behest of

JACK WARNER

, he came up with

three pseudonyms, Melville Crossman, Mark Canfield, and

Gregory Rogers, reserving his real name only for prestige

projects. Ironically, Melville Crossman became the most pop-

ular writer of the four of them, and (unwittingly) MGM tried

to hire the nonexistent screenwriter away from Warners.

Zanuck’s influence continued to grow, and he was pro-

moted several times until he finally became Jack Warner’s

right-hand man as head of production. In the meantime, he

either wrote or produced many of Warner’s most important

films, including the movie that began the talkie era, The Jazz

Singer (1927). Zanuck was responsible for much of Warner’s

early successes, introducing the

BIOPIC

cycle with Disraeli

(1929), the gangster cycle with Little Caesar (1931) and Public

Enemy (1931), the social consciousness cycle with I Am a

Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), and the revived musical

cycle with 42nd Street (1933).

In 1933, in a dispute with Harry Warner, Zanuck quit and

then teamed with Joseph M. Schenck at United Artists to

form their own film company, Twentieth Century Pictures.

The company was in business a scant but successful two years

before merging with the much larger but ailing giant, Fox

Film Corporation, becoming Twentieth Century–Fox in

1935. Zanuck was vice president in charge of production, a

title he held until 1956. In that capacity, he turned his newly

formed company into a profitable major studio with few stars

on his roster. Under his supervision, the studio put out so

many costume epics during the latter half of the 1930s that it

became known as 16th-Century-Fox.

During the early 1940s, Zanuck once again went off to war,

this time as a lieutenant colonel making documentary films.

On his return to the studio, he entered what many consider his

476

Z