Seely F.B. Analytical Mechanics for Engineers

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SIMPLE

CIRCULAR

PENDULUM

361

the

string.

Although

these

ideal

conditions cannot be

realized

fully

in

any

physical

apparatus,

the

motion of a small

body

sus-

pended

by

a

light

thread

will be

approximately

that

of the ideal

simple

pendulum.

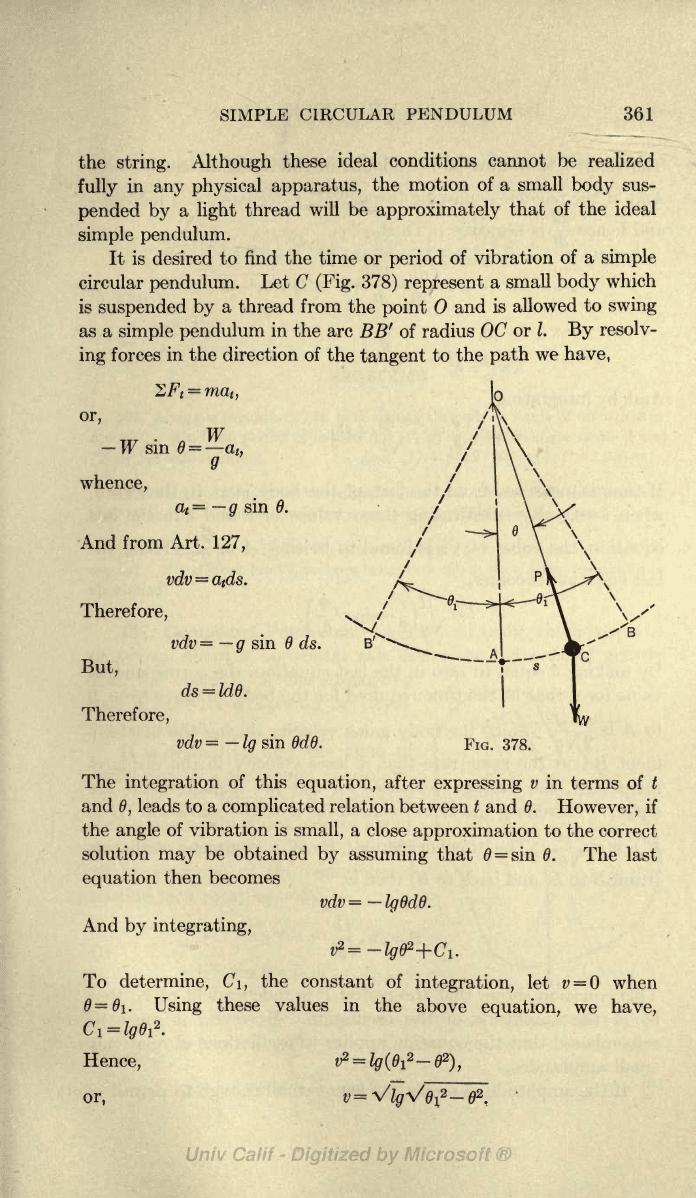

It

is

desired

to find

the time or

period

of

vibration

of a

simple

circular

pendulum.

Let

C

(Fig.

378)

represent

a small

body

which

is

suspended

by

a thread

from

the

point

and

is

allowed

to

swing

as a

simple pendulum

in

the

arc

BB

1

of

radius

OC

or

I.

By

resolv-

ing

forces

in

the direction of

the

tangent

to

the

path

we

have,

or

Sft-

w

W

sin

=

a*,

J/

whence,

Or

=

</

sin 0.

And

from Art.

127,

vdv=a

t

ds.

Therefore,

vdv

=

g

sin

ds.

But,

Therefore,

=

ld6.

vdv

=

lg

sin Odd.

FIG.

378.

The

integration

of this

equation,

after

expressing

v

in

terms of

t

and

6,

leads

to a

complicated

relation

between t

and

6.

However,

if

the

angle

of vibration is

small,

a

close

approximation

to the

correct

solution

may

be obtained

by

assuming

that

=

sin 6.

The last

equation

then

becomes

vdv=

IgBdB.

And

by integrating,

To

determine, Ci,

the

constant of

integration,

let

v

=

when

=

#i.

Using

these

values

in

the

above

equation,

we

have,

Hence,

or,

362

FORCE,

MASS,

AND

ACCELERATION

ds

The

time, t, may

now

be introduced

in

the

equation

since ^

-r-

And,

if

the

particle

is

moving

towards

A,

s

decreases as t

increases

ds

and hence

-j-

is

negative.

Thus,

or,

de

And, by integrating,

If time is measured

from

the instant the

body

is at

B,

then

=

Q\

when

2

=

0.

By substituting

these

values

of 6

and

t

in

the last

equation,

the value of

2

is found to be sin"

1

1 or

^-

Thus,

the

last

equation

becomes,

By

making

6

equal

to zero

in

the last

equation,

the

corresponding

value

for

t,

that

is,

the time

required

for

the

body

to move from B

to

A is

^A/-.

Since the

body gains velocity

during

the

displace-

ment

BA at

the

same rate that

it

loses

velocity

in the

displace-

ment

AB',

the

average

velocities for the two

displacements

are

equal.

Therefore,

the time

required

for a

single

oscillation

(B

to

B')

is TT

^-.

The time

or

period, P,

of a

complete

oscillation

(from

B

to

B' and back to

B)

then

is,

-2-J?

\0

This

equation

shows

that the

period

P

is

independent

of

6\,

that

is,

of

the

amplitude

of

the

oscillation.

However,

it must

be

remembered

that

the

equation

applies

to oscillations of

relatively

small

amplitudes.

Jf

the

amplitude

of

oscillation

is

not

small

enough

to

permit

of

COMPOUND

PENDULUM

363

the

assumption

that

sin

=

6,

then the time of a

complete

oscilla-

tion

is

expressed by

the

series,

in

which

k

=

sin

-.

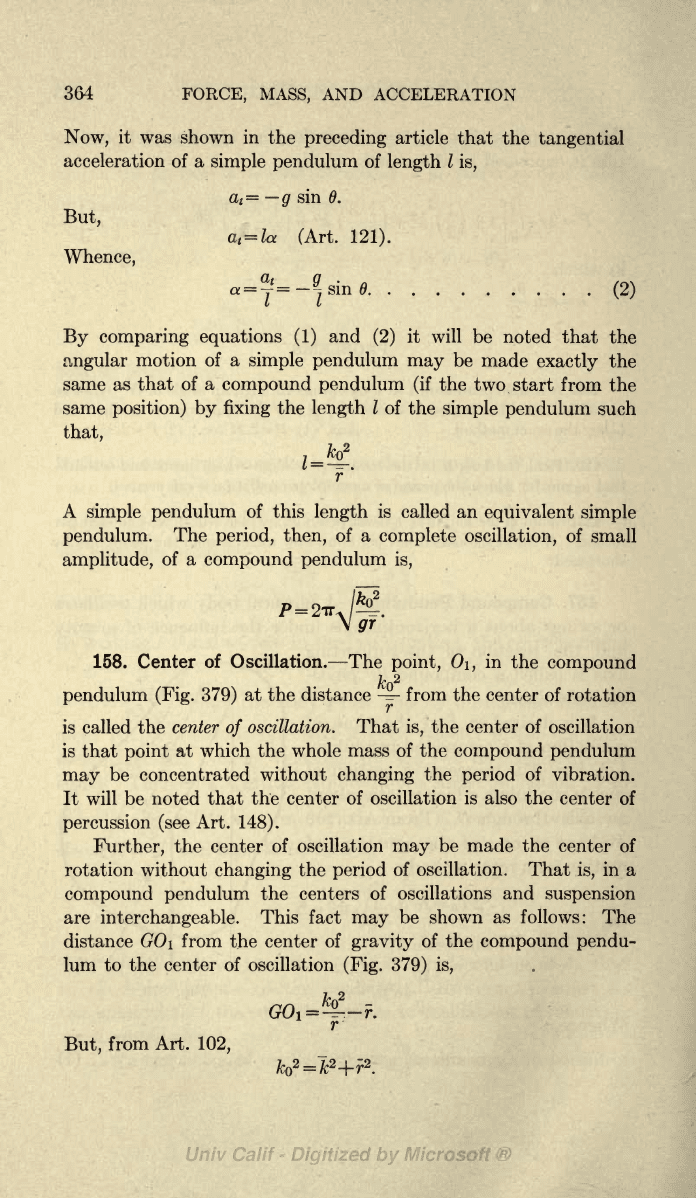

PROBLEMS

409.

A

simple pendulum

4

ft.

long swings through

an

angle

of 60

(that

is,

^=30).

Find the

period

of

oscillation,

(1)

by

the

approximate

method and

(2)

by

the exact

method.

Ans.

(1)

P =2.21

sec.;

(2)

P

=

2.25 sec.

410. Find the

length

of the

simple

pendulum

which beats

half-seconds,

that

is,

one for which

the

period

of a

complete

oscillation

is one second.

411. What is the

length

of

a clock

pendulum

which will make one beat

per

second.

If the

clock

loses 5 sec.

per

hour,

how much should the

pendulum

be

shortened?

157.

Compound

Pendulum. A

physical

body

which

oscillates

or

swings

about

a horizontal axis under

the influence of

gravity

and the

reaction of the

supporting

axis

is

called

a

compound

or

physi-

cal

pendulum.

It is desired to find the time of

oscillation of a

compound pendulum.

Let

Fig.

379

represent

a

section

of

such

a

pendulum

which

rotates about

an

axis

through

0. From

Art.

146

we

have as one

of

the

equations

of

motion

for a

rotating body,

Or,

Whence,

Wr

sin

=

7o

a

gr

=

-

<*=

f-o

sin 0.

364

FORCE,

MASS,

AND

ACCELERATION

Now,

it was shown in

the

preceding

article

that the

tangential

acceleration

of a

simple pendulum

of

length

I

is,

a

t

=

g

sin 6.

But,

a

t

=

la

(Art.

121).

Whence,

(2)

By

comparing equations

(1)

and

(2)

it will

be

noted

that the

angular

motion of a

simple pendulum

may

be

made

exactly

the

same

as that of

a

compound pendulum (if

the

two

start from

the

same

position)

by

fixing

the

length

I of

the

simple pendulum

such

that,

A

simple pendulum

of this

length

is

called an

equivalent

simple

pendulum.

The

period, then,

of

a

complete

oscillation,

of

small

amplitude,

of a

compound pendulum is,

P f)--

I"*

**'w

158. Center

of Oscillation.

The

point, Oi,

in

the

compound

pendulum (Fig.

379)

at the distance

~

from the

center

of

rotation

is called the

center

of

oscillation. That

is,

the center of

oscillation

is that

point

at

which

the

whole

mass

of the

compound pendulum

may

be concentrated

without

changing

the

period

of

vibration.

It will be

noted that the center

of oscillation is

also

the

center of

percussion

(see

Art.

148).

Further,

the

center of oscillation

may

be made the

center of

rotation without

changing

the

period

of oscillation. That

is,

in

a

compound pendulum

the centers of

oscillations and

suspension

are

interchangeable.

This fact

may

be shown

as

follows: The

distance

G0\

from

the

center of

gravity

of the

compound pendu-

lum

to the center of oscillation

(Fig.

379) is,

But,

from

Art.

102,

TORSION PENDULUM

365

Whence,

Now

if

Oi

is made the

center

of

rotation,

then the

new

center

of

k

2

oscillation,

02,

will be

a distance

G0%

from

the

center of

gravity.

But

r

is now

equal

to

G0\

; hence,

r 'i?

Therefore

0%

coincides with

0\

and

hence the

centers of

sus-

pension

and oscillation

are

interchangeable.

PROBLEMS

412.

A

uniform slender

rod

4

ft.

long

oscillates as a

compound

pendulum

about

a horizontal axis

through

one

end of the

rod,

the

rod

being

perpendicular

to the axis,

(a)

Find

the

period

of

oscillation.

(6)

About

what other

point

could

the rod

rotate and have the same

/~\0

period

of oscillation.

Ans.

(a)

P

=

1.80

sec.; (6)

1.33

ft. from end of

rod.

413. Find the

length

of a uniform

slender bar

having

a

period

of

oscillation

of

1

sec. when allowed to

swing

as

a

compound

pendulum

about

an axis

through

one end

of

the bar.

Ans. 1

=

1.22 ft.

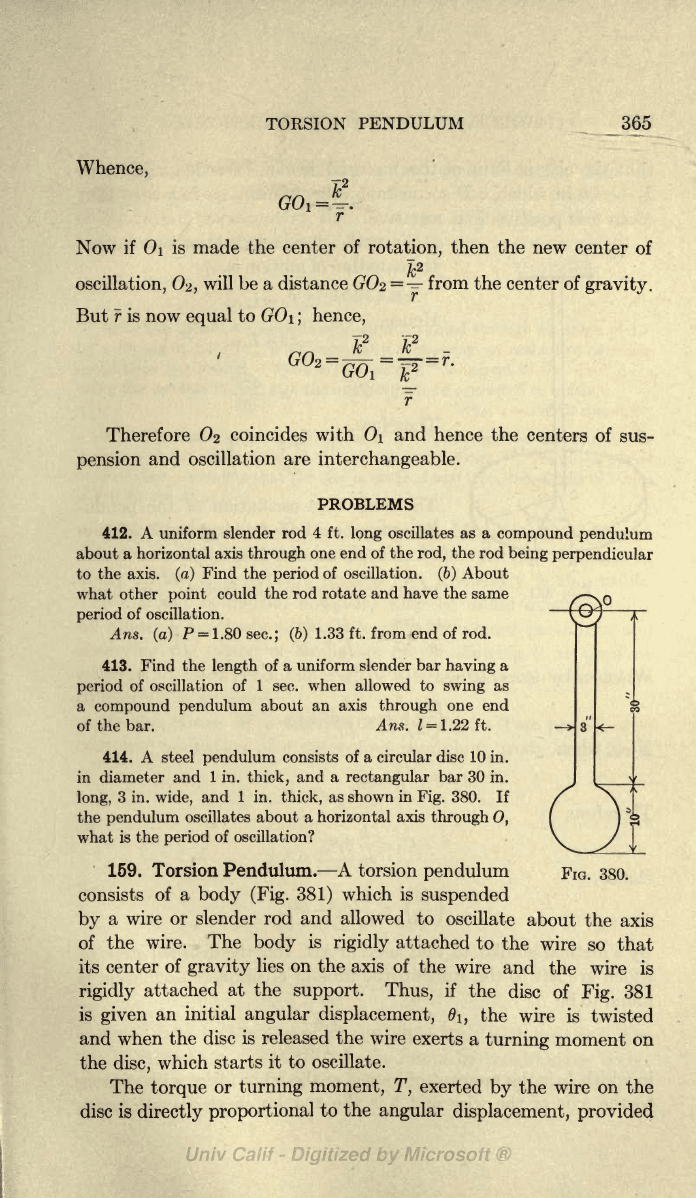

414. A steel

pendulum

consists

of a

circular disc 10 in.

in diameter

and

1

in.

thick,

and a

rectangular

bar

30 in.

long,

3

in.

wide,

and

1

in.

thick,

as shown

in

Fig.

380. If

the

pendulum

oscillates

about a horizontal axis

through

0,

what is

the

period

of oscillation?

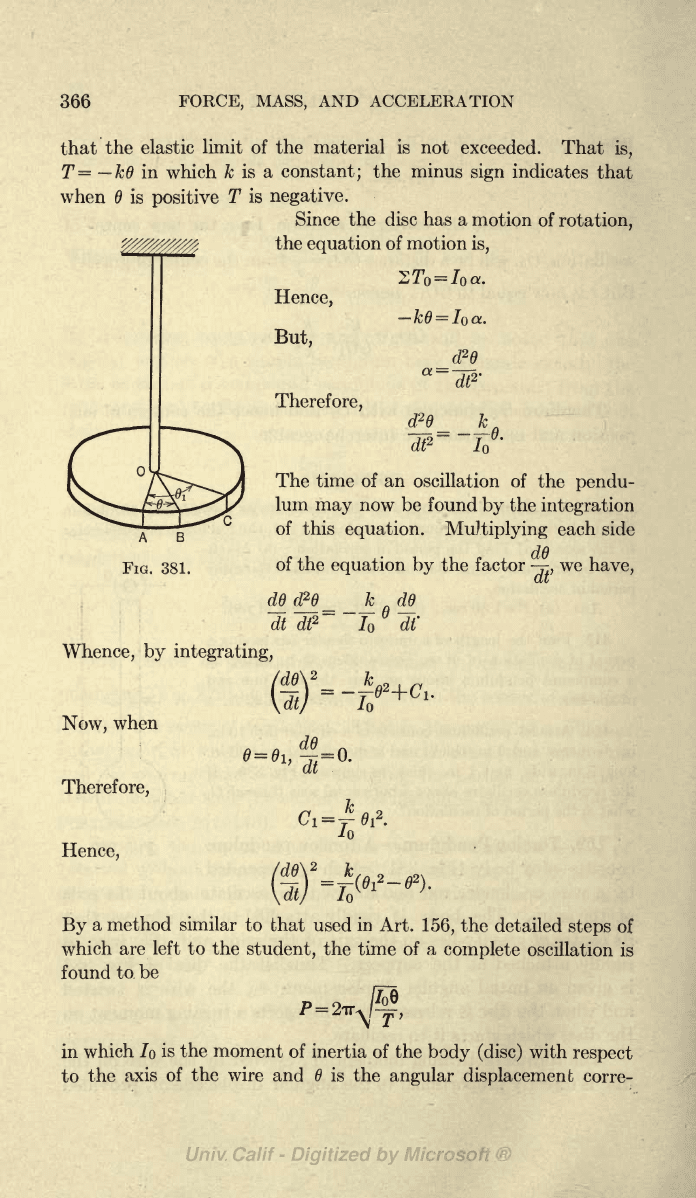

159.

Torsion Pendulum.

A

torsion

pendulum

FIG. 380.

consists

of a

body

(Fig.

381)

which

is

suspended

by

a wire

or slender rod

and

allowed to

oscillate

about

the

axis

of

the

wire.

The

body

is

rigidly

attached

to

the

wire

so that

its

center

of

gravity

lies on

the axis of

the

wire

and

the wire is

rigidly

attached

at the

support.

Thus,

if

the

disc

of

Fig.

381

is

given

an

initial

angular

displacement,

61,

the

wire is twisted

and when

the

disc

is released the

wire

exerts a

turning

moment

on

the

disc,

which

starts

it to oscillate.

The

torque

or

turning

moment,

T,

exerted

by

the wire

on the

disc is

directly proportional

to the

angular

displacement,

provided

366

FORCE,

MASS,

AND

ACCELERATION

that

the elastic

limit of the material is not

exceeded. That

is,

T=

kd in

which

ft is

a

constant;

the

minus

sign

indicates

that

when

9

is

positive

T is

negative.

Since

the disc

has a

motion

of

rotation,

the

equation

of

motion

is,

Hence,

But,

a

Therefore,

dt

2

'

00

_

k

W

To

9

'

The time of an

oscillation of

the

pendu-

lum

may

now be found

by

the

integration

of

this

equation. Multiplying

each side

of

the

equation by

the factor

-^,

we

have,

_

^

a

de

dt dP

IQ

df

Whence, by

integrating,

Now,

when

(

de

\

2

k

(dt)

=

-T

Therefore,

Hence,

By

a method similar

to that

used

in

Art.

156,

the

detailed

steps

of

which

are

left to

the

student,

the time of

a

complete

oscillation

is

found

to be

in which

IQ

is

the

moment of inertia

of

the

body (disc)

with

respect

to

the

axis

of the

wire

and

B

is the

angular displacement,

corre-

DETERMINATION

OF MOMENT OF INERTIA

_367

spending

to

which

the wire

exerts the

torque

T

on the

disc.

It

will

be observed

that

the

period

of an

oscillation

is

independent

of the

initial

displacement,

that

is,

of the

amplitude

of

the vibra-

tion,

assuming

that

the elastic

limit of the wire is not

exceeded.

PROBLEMS

415. The disc

of a torsional

pendulum

is turned

through

an

angle

of

10

by

a

torque

of

1

ft.-lb. When released it

is

observed

to make five

complete

oscillations

per

second. What is the

moment of

inertia

of the

disc?

(In

using

the

formula of Art.

159,

the

angle

must be

expressed

in

radians).

Ans. 7

=

.00582slug-ft.

2

416. The

disc

of a torsional

pendulum

is

1

ft. in

diameter and

2

in. thick.

A

torque

of

1

ft.-lb. is

required

to turn the disc

through

8.

Find the

period

of

oscillation,

assuming

that the disc is made

of

cast

iron,

the

weight

of which

is

450 Ib.

per

cubic foot.

160.

Experimental

Determination

of

Moment of Inertia.

As

noted

in

Art.

106,

the calculation of the

moment

of inertia

of

many

bodies is a difficult

process

and

frequently

is

impossible.

The moment of

inertia, however,

may

be found

experimentally

by

allowing

the

body

to oscillate as a

compound

pendulum

and

observing

the

period

of

oscillation or

by

allowing

it

to oscillate

either as a

torsion

pendulum

itself or

with a

given

torsion

pendulum

to

which it

is attached.

/.

By

Means

of

a

Compound

Pendulum.

The

period

of

a

complete

oscillation of a

compound

pendulum,

from

Art.

157,

is

P

=

27TA/^.

gr

Or,

P

2

_

But,

g

Hence,

_MP

2

_

_

WP

2

r

=

~4^~

gr

~~

~b?~'

in

which

Jo

is the moment of

inertia

of

the

body

with

respect

to the

axis of

suspension

Now

W

may

be

found

by

weighing

the

body,

r

by

balancing

the

body

over

a

knife

edge,

and

P

by

observing

the

period

jDfjDScillation

.

368

FORCE,

MASS,

AND

ACCELERATION

After

7o

is

found,

the moment

of

inertia

with

respect

to a

parallel

axis

through

the mass-center

(7)

may

be

calculated from

the

equation,

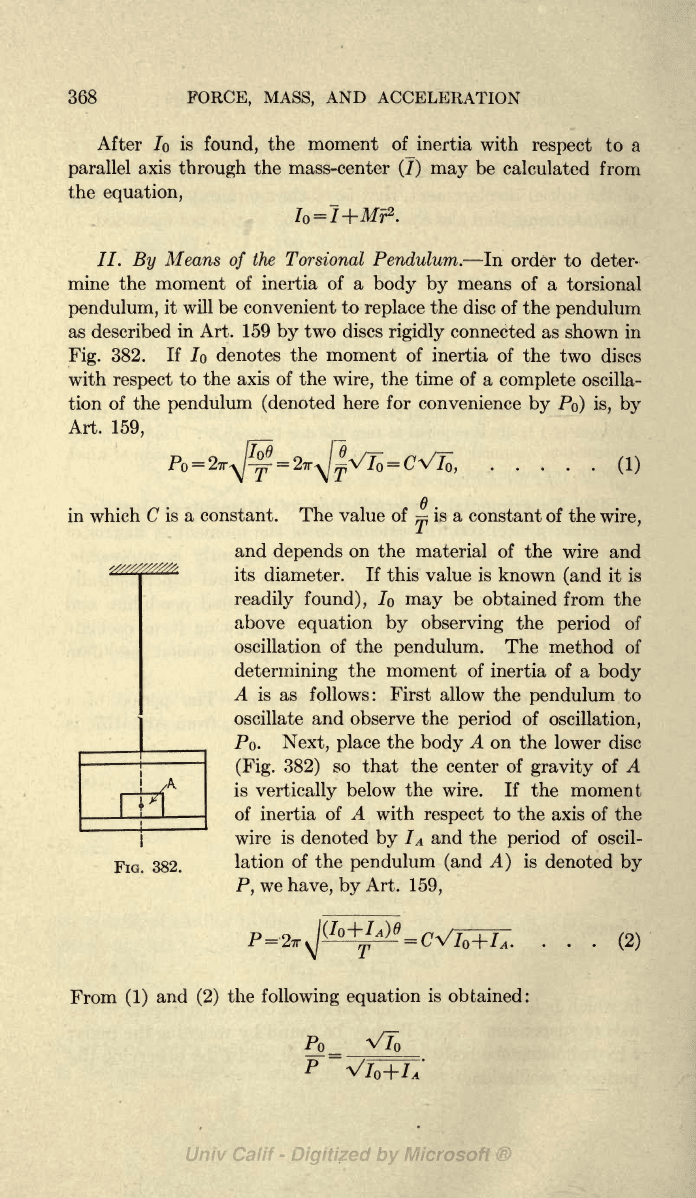

II.

By

Means

of

the Torsional Pendulum.

In

order to

deter-

mine the

moment of inertia of a

body by

means

of a

torsional

pendulum,

it will

be convenient to

replace

the disc

of the

pendulum

as described

in Art. 159

by

two discs

rigidly

connected as

shown

in

Fig.

382.

If

/o

denotes

the

moment of

inertia of

the

two discs

with

respect

to the

axis of

the

wire,

the time

of a

complete

oscilla-

tion of the

pendulum

(denoted

here for

convenience

by

PO)

is, by

Art.

159,

.....

(1)

in which

C is a

constant. The

value

of

^

is a

constant of the

wire,

and

depends

on

the material of

the wire

and

its diameter.

If

this value is

known

(and

it is

readily

found),

/o

may

be

obtained

from

the

above

equation

by

observing

the

period

of

oscillation of

the

pendulum.

The

method

of

determining

the moment of

inertia of

a

body

A

is as follows: First

allow the

pendulum

to

oscillate

and observe

the

period

of

oscillation,

PO-

Next,

place

the

body

A

on the

lower

disc

(Fig.

382)

so that the center of

gravity

of

A

is

vertically

below

the

wire.

If

the moment

of

inertia

of A

with

respect

to the

axis

of the

wire

is denoted

by

I

A

and

the

period

of oscil-

lation

of the

pendulum

(and A)

is

denoted

by

P,

we

have,

by

Art.

159,

FIG.

382.

...

(2)

From

(1)

and

(2)

the

following

equation

is

obtained:

P

VT

NEED

FOR

BALANCING

363

That

is,

Hence,

It

may

be

noted that

if the discs

are

of such

form that their

moment

of inertia

may

be

calculated it

is not

necessary

to

know

the

con-

P

2

T

_

T I

L

1

A -tOl ^m

stant

;~,

of

the

wire.;

PROBLEMS

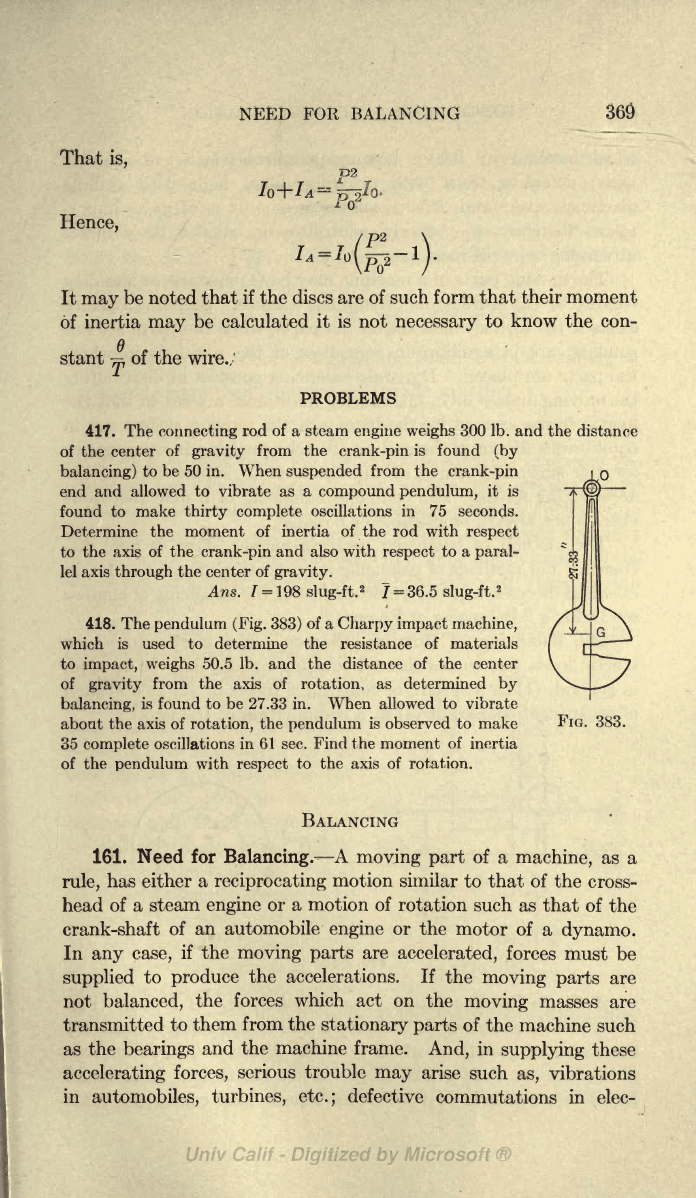

417.

The

connecting

rod

of

a steam

engine

weighs

300

Ib. and

the distance

of

the center

of

gravity

from the

crank-pin

is found

(by

balancing)

to be 50 in. When

suspended

from the

crank-pin

end and

allowed

to

vibrate

as a

compound

pendulum,

it is

found

to make

thirty

complete

oscillations

in

75 seconds.

Determine

the moment of inertia of the rod with

respect

to the

axis of the

crank-pin

and also

with

respect

to a

paral-

lel axis

through

the

center

of

gravity.

Arts.

/

=

198

slug-ft.

2

7

=

36.5

slug-ft.

2

418. The

pendulum

(Fig.

383)

of a

Charpy

impact

machine,

which

is

used to

determine the resistance

of materials

to

impact,

weighs

50.5 Ib.

and

the

distance

of the

center

of

gravity

from the

axis

of

rotation,

as

determined

by

balancing,

is found to be

27.33

in. When allowed

to

vibrate

about the axis of

rotation,

the

pendulum

is observed

to make

FIG.

383.

35

complete

oscillations

in 61 sec.

Find

the moment

of

inertia

of the

pendulum

with

respect

to

the axis

of

rotation.

BALANCING

161.

Need for

Balancing.

A

moving

part

of a

machine,

as a

rule,

has either

a

reciprocating

motion

similar to

that of

the

cross-

head

of a steam

engine

or a motion of

rotation

such

as that

of

the

crank-shaft

of an automobile

engine

or the

motor

of

a

dynamo.

In

any

case,

if the

moving

parts

are

accelerated,

forces

must be

supplied

to

produce

the accelerations. If

the

moving

parts

are

not

balanced,

the

forces which act on

the

moving

masses

are

transmitted

to them

from the

stationary

parts

of

the

machine such

as the

bearings

and

the machine

frame.

And,

in

supplying

these

accelerating

forces,

serious trouble

may

arise

such

as,

vibrations

in

automobiles,

turbines,

etc.;

defective

commutations in elec-

370

FORCE,

MASS,

AND

ACCELERATION

trical

machinery;

heavy

bearing

pressures

which

cause

undue

wear;

defective work with

grinding

discs,

high-speed

drilling

machines,

etc.;

and defective lubrication.

It is of

great impor-

tance,

therefore,

to

properly

neutralize or balance these

forces

in

various

types

of

machines.

The

moving parts

of

a machine

may

be

(1)

in

static or

standing

balance or

(2)

in

dynamic

or

running

balance.

Standing

balance

exists

if the

forces which act on the

parts,

when the

parts

are not

running,

are

in

equilibrium

regardless

of the

positions

in

which

the

parts

are

placed.

Dynamic balancing

consists in

distributing

the

moving

masses or

in

introducing

additional masses so

that

the

inertia

forces

exerted

by

the masses of the

moving system

are

in

equilibrium amongst

themselves,

thereby making

it

unnecessary

for the

stationary parts

of the machine

to

supply

any

of the

accelerating

forces.

The

complete

balancing

of a

machine,

how-

ever,

is

not

always practicable

or

possible.

The method of

balancing rotating masses,

only,

is here dis-

cussed. For methods of

balancing reciprocating

masses

and for

an

excellent discussion of

the whole

subject

of the

balancing

of

engines

see

Dalby's

"

Balancing

of

Engines."

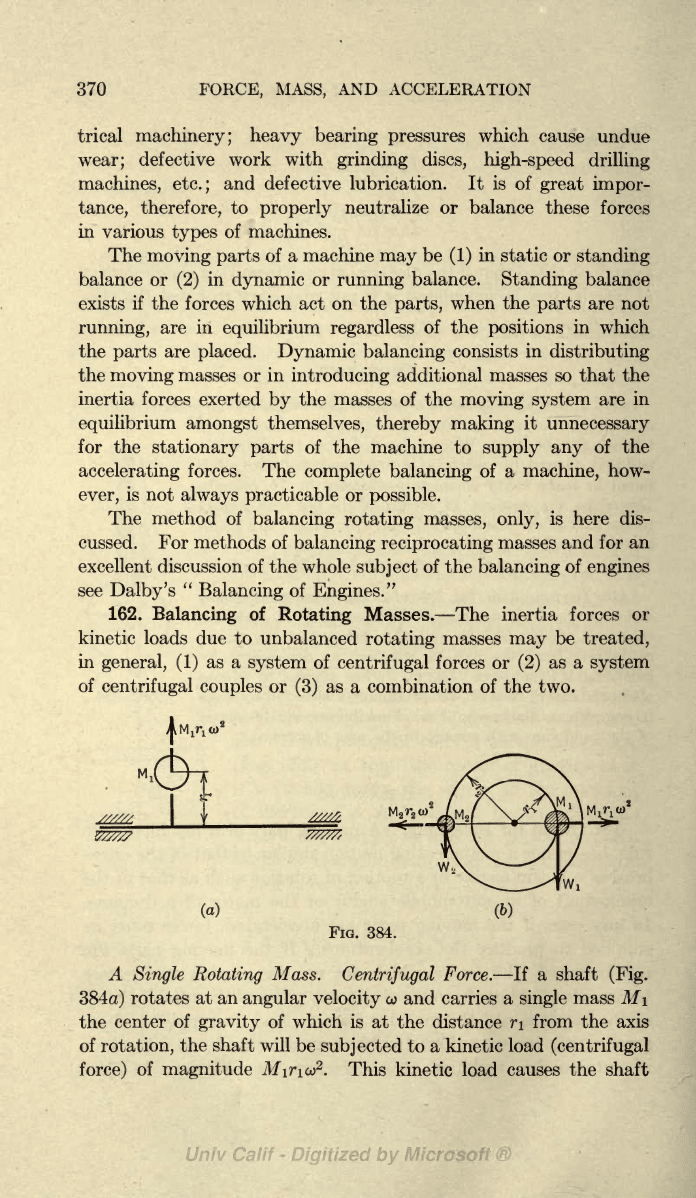

162.

Balancing

of

Rotating

Masses.

The inertia

forces or

kinetic loads due

to

unbalanced

rotating

masses

may

be

treated,

in

general,

(1)

as

a

system

of

centrifugal

forces

or

(2)

as a

system

of

centrifugal couples

or

(3)

as a combination of the two.

(a)

FIG.

384.

A

Single Rotating

Mass.

Centrifugal

Force.

If a shaft

(Fig.

384a)

rotates at

an

angular velocity

a>

and carries a

single

mass

MI

the

center

of

gravity

of which is at the distance

r\

from

the

axis

of

rotation,

the

shaft

will be

subjected

to a

kinetic

load

(centrifugal

force)

of

magnitude

M

\riu>

2

.

This

kinetic

load

causes the shaft