Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

tria launched a performing rights society in 1897, but similar societies

were not founded in the United Kingdom and the United States until

1914.

The British public viewed copyright law with much suspicion be-

cause of the notorious activities of Harry Wall in the 1870s.

99

Wall’s

strategy was to buy up old copyrights and then find performers who

were “guilty” of infringement. He issued them with a £2 demand, backed

up by threats of legal action. He intimidated them further by claiming

he acted for the Copyright and Performing Right Protection Office

(which he had cunningly set up himself in 1875). Legislation was in-

troduced in 1882 against “vexatious proceedings” of this kind, but it

failed to stop him; only the Copyright (Musical Compositions) Act of

1888, which placed the assessment of damages for breach of copyright

in the court’s hands, did so.

100

As they had been doing for more than

thirty years, SACEM continued to collect fees for performances in

Britain, though many did not like it. After the British Copyright Acts of

1882 and 1888, publishers had to announce on their sheet music

whether or not a piece could be performed in public without a fee.

However, far from thinking that performers should be obliged to pay to

perform a piece of music, some publishers were, instead, willing to pay

performers to promote their music. That is how drawing room ballads

attracted the name “royalty ballads” in the later decades of the century.

The names of the singers would be printed conspicuously on the title

page in order to encourage sales. Publishers and composers were, in

general, much more concerned about piracy than performing rights.

One gains a general impression—albeit very difficult to substanti-

ate with hard facts—that publishers were exploiting most British and

American composers in the nineteenth century. They were glad to be

published and earn anything they could, and they had no idea how to

better their relations with publishers, or how to exercise any kind of in-

tellectual property rights. Stephen Foster may have been the most

commercially successful songwriter of the 1850s, but his average an-

nual income from royalties was only $1,371.92.

101

French songwriters

were in the strongest position, having the protection of SACEM. In

Austria, the United Kingdom, and the United States, composers associ-

ated their income with sales of sheet music, not with performing rights.

Early copyright legislation favored publishers and did not offer much

protection to authors and, what is more, had to be registered separately

in different countries. An attempt to establish a reciprocal copyright

agreement between the United States and Britain was made in 1852,

but it fell through.

102

In 1855, Hall and Son created a storm by an-

nouncing that they were discounting the price of noncopyrighted for-

eign music, while maintaining the price of American music. Other pub-

lishers tried to organize a boycott, but Hall’s business boomed. The

recently formed Board of Music Trade had to agree to an across-the-

board cut of 20 percent on noncopyrighted music.

103

32 Sounds of the Metropolis

Publishers had other problems besides competition and rivalry; they

also had to deal with the vagaries and unpredictability of the customer.

Chappell made a huge profit after acquiring the British publishing

rights in Gounod’s Faust for a meager payment of around £100, prompt-

ing Boosey to jump in immediately with an offer of £1,000 for Gounod’s

next opera, Mireille. Alas, it flopped. Nevertheless, Boosey managed to

buy for £100 the rights to Lecocq’s La Fille de Madame Angot, which

proved to be one of the most popular operettas of the century.

104

Boosey

acquired the British copyright of nearly all Offenbach’s stage works,

while Chappell owned the rights to those of Gilbert and Sullivan.

During 1878, when forty-two companies in America were staging

versions of H.M.S. Pinafore, Gilbert and Sullivan were left to consider

uncomfortably that this popularity was worth nothing to them in fi-

nancial terms because of inadequate international copyright laws. They

hit on the idea of taking over a company from Britain to perform their

next comic opera in the United States, so that they would be ahead of

the game. The world première of The Pirates of Penzance, therefore, took

place at the Fifth Avenue Theater, New York, on 31 December 1879.

The score remained in manuscript, since its publication would have al-

lowed anyone to make use of it. However, this was not their only prob-

lem, as Sullivan explained:

Keeping the libretto and music in manuscript did not settle the difficulty,

as it was held by some judges that theatrical representation was tanta-

mount to publication, so that any member of the audience who managed

to take down the libretto in shorthand, for instance, and succeeded in

memorizing the music was quite at liberty to produce his own version

of it.

105

Sullivan even found that members of the orchestra were being offered

bribes to hand over band parts. An additional complication was that a

performance in England prior to one in America was necessary to ac-

quire British copyright protection. Thus, a one-night performance at

the small Royal Bijou Theatre in the seaside resort of Paignton took

place a few hours before the New York performance.

106

It was out of

the way and poorly advertised, in order not to spoil the British launch

at the Opera Comique in London a few months later.

Piracy was rife, and not just in instances such as Gilbert and Sulli-

van faced, or in the trade of itinerant ballad vendors out on the streets

(a trade on the wane in the 1870s). The Music Publisher’s Association

asked the Musical Opinion and Music Trade Review in 1882 to warn read-

ers that copying a copyrighted song by hand was an infringement, de-

spite the fact that advertisements in journals “circulating primarily

among ladies” offered to undertake this work.

107

The practice of mak-

ing manuscript copies of music continued to cause publishers concern,

especially when trade was slow in the later 1880s. Some people thought

that transcribing a song into another key was perfectly acceptable.

Professionalism and Commercialism 33

The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic

Works took place in 1886, and ended with an agreement that copyright

protection for authors would exist in the fourteen nations that signed

up for it; but the United States was not a signatory. In 1888, American

copyright law was changed to give reciprocal rights to American and

British composers, and the 1891 American act extended this, offering

28 years’ protection to authors from countries that had reciprocal copy-

right relations with the United States. SACEM then opened a New York

office, as did Boosey and Chappell. New York’s Witmark made a co-

publication arrangement with London’s Charles Sheard, and Harms did

likewise with Francis, Day and Hunter.

Toward the end of the century, arguments raged about cuts in the

retail price of music; some wholesalers were castigated for discounting

the trade price when negotiating with dealers, or when selling to schools

or professional musicians. The accepted system was that the publisher

produced the item at a certain cost, and added a little extra when sell-

ing to the wholesaler; then the retailer bought from the wholesaler at

a trade price and sold it to the customer at the retail price.

108

The Star System

It may well be argued that there were stars before the nineteenth cen-

tury, especially in the ranks of singers, and in the first half of the nine-

teenth century there was certainly no shortage of instrumental virtu-

osos who might fit that description. The modern type of star, however,

emerges with the entertainment industry and is differentiated by the

way he or she is turned into a commodity: for example, Johann Strauss

Sr. becomes the Waltz King and Jenny Lind the Swedish Nightingale.

However, in the early days they still tended to be treated as individuals

possessing unique talents, rather than being promoted as part of a sys-

tem of business-driven entertainment in which they might feature al-

most interchangeably as “top of the bill” artists, as did the lions comiques

in London music halls. The earlier entrepreneurial musicians usually

managed themselves, but those in the second half of the century were

more likely to seek the services of agents, entrusting to them the sched-

uling of their appearances and the bargaining over fees. Strauss Sr.

planned his own tours, but by the end of the century Vienna’s cele-

brated musicians looked to the agent Albert Gutman for help.

109

More-

over, there was an advantage from the concert promoter’s point of

view, in that alternatives could be considered, since agents would have

a variety of musicians on their books. Some of the earliest agents were

music publishers.

The first star of the café-concert (the French term is vedette) was

Thérésa (1837–1913; real name Emma Valadon). She was a sensation

at the Eldorado in 1863, and was soon offered a large increase in salary

(from 200 to 300 francs a month) to tempt her to the Alcazar.

110

Popu-

34 Sounds of the Metropolis

lar performers could now become very wealthy, and those who offered

a rags-to-riches story were, in Attali’s words, “a formidable instrument

of social order, of hope and submission simultaneously.”

111

Paulus

(Jean-Paul Habans) became the foremost French male star after devel-

oping a unique jerky style (style gambillard) in the 1880s.

112

The star sys-

tem relies on the existence of similar performance spaces that can be

visited by these artists; thus, the metropolis offers an ideal environment.

The star system became an important feature of London music hall

after 1860: George Leybourne, the Great MacDermott (Michael Farrell),

Jenny Hill, Albert Chevalier, Gus Elen, and Marie Lloyd were among

the most admired. Alexander Girardi was the preeminent Viennese

star: he sang the Wiener Fiakerlied (Pick) in the Viennese vernacular and

persuaded people, as did Gus Elen in London, that he was merely being

himself rather than putting on an act (even his Italian roots didn’t

counter the impression of authenticity). Girardi also sang in operetta,

and was much applauded in the role of Zsupán in Der Zigeunerbaron.

The glamorous female star was a feature of operetta: Hortense Schnei-

der became famous in the title role of La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein

after its tremendous success during the Paris Exhibition of 1867.

113

Emily Soldene was Schneider’s counterpart in London,

114

as Marie

Geistinger was in Vienna; Vienna also had an operetta star in Josephine

Gallmeyer, and New York had Lillian Russell.

115

The European aristocracy began to find themselves unable to af-

ford the high fees of international stars for their private concerts, and

their salons were on the wane during the second half of the century.

Liszt’s recitals took on much of the character of the aristocratic salon,

involving socializing, drinking, and smoking. He appeared at the high-

est-status public venues at the highest prices. Wagner, attending a re-

cital in Paris, wrote that tickets cost 20 francs, providing Liszt with

10,000 francs for one concert.

116

Strauss Sr. achieved international star-

dom as a consequence of touring with his orchestra (see chapter 5).

However, this course of action did not always guarantee sensational

success. Josef Gung’l toured—even as far as North America in 1849—

but did not attain the same individual acclaim; he became known only

as the Berlin Strauss. However, his waltz Die Hydropaten (1858) lent its

name to a group of pioneers of cabaret artistique in Paris (see chapter 8).

Setting the trend for the emergence in the later twentieth century of a

“pop aristocracy,” the chansonnier Aristide Bruant and Johann Strauss

Jr. both bought themselves country estates on their profits.

Among the stars of the Monday Popular Concerts in the 1860s

were the pianist Arabella Goddard and the tenor Sims Reeves, for

whom Balfe had composed “Come into the Garden, Maud” (Tennyson)

in the previous decade. John Boosey discussed the possibility of hold-

ing ballad concerts with the singer Madame Sainton Dolby, and put on

the first in 1867 at St. James’s Hall. He may have been influenced by

the success of ballad entertainments at the Crystal Palace the previous

Professionalism and Commercialism 35

year, which one critic described as “far superior to those of a similar

kind which have taken place in the metropolis.”

117

In the 1840s and

1850s an opportunity had arisen in the drawing room ballad market for

women songwriters, including those like Caroline Norton, who wrote

both verse and music. In the 1860s, women had become a powerful

force in this market, many of them being published by Boosey. Perhaps

the most commercially successful of all nineteenth-century women

songwriters was Claribel (Charlotte Alington Barnard), whose songs

were favorites in British and American homes from the 1860s to the

1880s.

118

For his ballad concerts, Boosey engaged star singers who could

attract a large public, such as Sims Reeves.

119

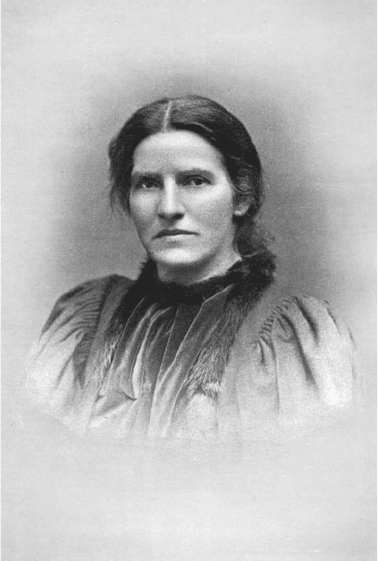

One of the greatest stars

proved to be the contralto Antoinette Sterling, born in Sterlingville,

New York, 1850 (see fig. 1.2). She chose this type of career quite delib-

erately—although her training had equipped her for a range of op-

tions—having studied with the famous singing teacher Manuel Garcia

(who had trained Jenny Lind and a host of others) and his daughter

Pauline Viardot. Sterling made an abundance of money from ballad

singing, since she had contracted to receive a royalty for a term of years

on many extremely popular ballads, such as Sullivan’s “Lost Chord”

and Molloy’s “Love’s Old Sweet Song.”

120

36 Sounds of the Metropolis

Figure 1.2

Antoinette Sterling.

Again we find that the music business does not always succeed in

achieving its desired goals: “I used to find ballad concerts handicapped,”

John Boosey’s nephew William lamented, “by it being necessary so

very frequently to repeat the same songs over and over again.”

121

If

many in the audience already possessed those songs, then it meant no

new business, and no additional royalty payment for the singer. A pos-

itive feature of the ballad concerts for impecunious composers was that

they could witness what was going down well with the audience and

try to repeat it. The consequence of this, however, was that the variety

of musical forms found in ballads, as well as variety of subject matter,

declined from the 1870s on, and publishers began looking out for com-

posers who might be thought to have found a formula for commercial

success.

122

In the 1880s, publishers trying to break into the New York

market learnt from London practice and began paying singers a royalty

of 6 to 14 cents per copy sold if they would promote their songs. The

equivalent type of bourgeois popular song in Paris is represented by the

romance.

123

It grew originally out of opera comique, and is characterized

by elegant lyricism and simple strophic form (and should not to be con-

fused with the later, more harmonically complex mélodie). The romance

was associated with the bourgeois salon and was as market oriented as

the drawing room ballads in London or New York. Some romances were

published in popular periodicals—one such was actually called La Ro-

mance. They differed from the English and American ballads in their

lack of inhibition about the subject of love.

In concluding this chapter on professionalism and commercialism

in music during the nineteenth century, it should be stressed that the

status of popular music changed profoundly with the development of

the music market. This may be summarized as follows. In the early days

of commercialization, the popular was condemned as being vulgar only

if it was considered to be pandering to low taste, but as the music in-

dustry grew, the more successful music was commercially, the more it

was perceived as music that appealed to a low and unrefined taste,

until all music written for sale was regarded as inferior. However, music

that was not thought to have originated as music for sale was still able

to sell in huge numbers—as did the vocal score of Messiah, the song-

sheet of the folk song “The British Grenadiers,” and the collection

Hymns Ancient and Modern (1861)

124

—and remain popular without

being despised as low in status and without its provoking critical con-

tempt. I consider these matters in more detail in chapter 4.

Professionalism and Commercialism 37

2

New Markets for

Cultural Goods

38

The critic Henry Lunn, writing in the Musical Times in 1866, was forced

to recognize that art now had to “take its place in the market with other

commodities.”

1

He conjured up a nostalgic vision of a supposed single

culture of former times, and yearned for “one grand association for the

presentation of the greatest orchestral works, which should include all

the available talent in the metropolis”;

2

social reformers’ ideal, too, was

a single, shared culture, uniting different classes and ethnic groups. But

the reality was that the economics of cultural provision in the second

half of the century necessitated focusing on particular consumers. Old

markets had to be developed, new ones created, and where necessary,

demand stimulated. In this chapter I am using the term “markets” be-

cause it makes more sense in the context of a capitalist economy than

speaking of individuals. No longer did individual patrons set the agenda

for the production of the majority of cultural artifacts; rather, it was the

market place. The reason markets were growing in the city was simple:

this was a period of urbanization in which city populations increased

rapidly as people arrived looking for work or business opportunities.

Georg Simmel, in his essay “Die Grossstädte und das Geistesleben”

(1902–3), notes that the form of supply in the metropolis is almost en-

tirely by “production for the market” instead of via personal relations

between producer and purchaser. The “struggle with nature for liveli-

hood” is transformed by the metropolis into an “inter-human struggle

for gain, which here is not granted by nature but by other men.”

3

These

markets targeted groups of consumers, setting out their stalls to attract

and profit from a city’s highly differentiated social strata—people of dif-

ferent social backgrounds, needs, and interests. The diverse markets for

cultural goods were noted in London at midcentury: “The gay have

their theatres—the philanthropic their Exeter Hall—the wealthy their

‘ancient concerts’—the costermongers what they term their sing-

song.”

4

Cultural value fluctuates with the consumer’s social status and

power to define legitimate taste. A cultural struggle occurs when a cur-

rent market’s values are upset by the formation of a rival market, as

shown in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience (1881), when Bunthorne the

fleshly poet and Grosvenor the idyllic poet compete for aesthetic status.

Urban residence was vital to entrepreneurship: it was in cities that

those in the business of culture looked for profit-making opportunities,

for markets that might be developed, and for art worlds that might be

extended or freshly created. In the 1860s, the institutions of the café-

concert in Paris and the music hall in London were the sites of new and

expanding networks of stage managers, lighting experts, venue man-

agers, poster designers, and so forth. The venture capitalist, however,

needed investment to open up a market, and it was in the city, too, that

financial backing was to be found. For some, there was a tendency to

self-promote aggressively, or to make overblown claims for their prod-

ucts, and “charlatan” became a common term of abuse for those who

did so.

5

As the nineteenth century wore on, an entrepreneur was seen

as someone risking capital, whether in building a business or in finan-

cial speculation. As noted in chapter 1, it might be a music publisher

making an investment in lithography, or raising funds to open a piano

factory, or sponsoring a concert series.

The biggest and most obvious change musicians faced in the early

nineteenth century, though London musicians had been prepared in

advance for this and Viennese musicians did not confront it till later,

was that they had to deal with markets and market relations rather

than patrons and patronage. Musicians were now placed in a situation

that gave rise to conflict between their need to affirm capitalist rela-

tions, in order to earn a living, and a desire to transgress them, in order

to assert artistic freedom. Yet musicians were not the only ones caught

up in this paradoxical situation, since music promoters were often torn

between their materialist interests and those that they may have felt to

be spiritual or aesthetic. The problem is that these interests are some-

times drawn together in a compromising fashion. It may be recalled

that, in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience, the complete transformation of

the plain-speaking soldiers into aesthetes is effected for decidedly ma-

terialistic and self-serving reasons.

Aristocratic taste in the eighteenth century was for ceremony and

formality; the bourgeoisie reacted against this by prizing individual

character and feelings. The fondness of the bourgeoisie for virtuosos,

Leonard Meyer suggests, was because virtuosos were understood to

possess innate gifts that were not dependent on lineage or learning.

6

A

New Markets for Cultural Goods 39

“natural” music was preferred that did not rely on previous informed

knowledge. The dislike for rules and conventions, linked to a new trust

in the spontaneous verdict of the people, is found in Richard Wagner’s

Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1867) when Hans Sachs asserts that if a mu-

sician follows nature’s path, it will be obvious to those who “know

nothing of the tablature.”

7

The subject of love was favored because it

cuts across class, as Earl Tolloller acknowledges with irony in his song

“Blue Blood” in Iolanthe (1882).

Hearts just as pure and fair

May beat in Belgrave Square

As in the lowly air

Of Seven Dials!

A way of avoiding art that relied on an education many people did

not possess (such as knowledge of classical antiquity) was to choose

contemporary topics and to celebrate the modern rather than the old

features of everyday life. The titles given to many Viennese waltzes,

and the ideas that frequently acted as inspiration, are examples of this

practice. The values of novelty and individuality related to bourgeois

ideology, being the virtues prized by “leaders of industry.”

8

Popular

forms with a working-class base were more likely to offer participation

(for example, the music hall song’s chorus); higher forms were more

likely to be objects of aesthetic contemplation. The greater the stress on

the aesthetic object, such as the priority of form over function, the

more likely it was to cause confusion or attract ridicule. In Gilbert and

Sullivan’s Ruddigore (1887), it is said jokingly that the villagers are odd

because they go around singing in four-part harmony. Suddenly the

artificial norms of opera stand exposed.

It was assumed that audiences with a higher class of musical taste

attended the Philharmonic Society’s concerts, and that those with less

elevated taste were more interested in oratorio. The Sacred Harmonic

Society had a chorus and orchestra totaling 300 in 1836, and it had in-

creased to 700 by the time Michael Costa became conductor in 1848.

The Society met in Exeter Hall and survived until 1888.

9

The issue of

taste, however, was more closely aligned to matters of respectability

and class status than to questions of aesthetics. A shopkeeper, for in-

stance, would have had no difficulty becoming a member of the Sacred

Harmonic Society, but Reginald Nettel reports that a tradesman was al-

most rejected as a member of the Philharmonic Society until an assur-

ance was given that “he did not serve behind the counter.”

10

A similar

distinction of class and taste existed in London theaters, especially be-

fore the Theatres Act of 1843, when only three theaters (Covent Gar-

den, Drury Lane, and the Haymarket) had been allowed to produce “le-

gitimate” drama—that is, drama without music. The minor theaters,

presenting their mixtures of songs and plays, were not regarded as re-

40 Sounds of the Metropolis

spectable venues, and the numbers of prostitutes in the neighborhoods

of such theaters added pressing moral concerns.

New markets developed for cultural goods, but each market needed

to be suitable for the different classes and class fractions that wished to

acquire these goods. A Viennese aristocrat, for example, might balk at

attending a concert in a bourgeois salon. Ruth Solie warns about the

confusion of applying latter-day ideas of salon music—as something

akin to parlor music—to the earlier days of salon concerts.

11

The key

questions are “Whose salon?” and “What was its social function?” The

salons of the old aristocracy in Vienna, for instance, were found by Tia

DeNora to play a role in the development of the concept of “serious

music.”

12

All classes had to take into account the character of a per-

formance venue before stepping inside, even though a certain amount

of class mixing was normal at musical entertainments. Depending on

where the entertainment was held, classes could separate themselves in

various ways—by occupying differently priced seats, or reserving boxes,

or booking special tables. In Paris, a cabaret artistique was not a place in

which working-class people felt at home, but neither was it suited to

the lower-middle-class clientele of the Divan Japonais. Yvette Guilbert

says it was a revelation for the audience at that establishment when she

began singing chansons from the most celebrated of cabarets, the Chat

Noir. She then moved further upmarket to perform at the bourgeois

Théâtre d’Application and, by the mid-1890s, any subversive quality

Guilbert may once have possessed was dissipated (see chapter 8).

Promenade Concerts

These concerts, which began in the 1830s, were the largest kind of pub-

lic concert, and during them people could display any manner of inat-

tentive listening—walking, talking, drinking, or eating. For this reason

they often took place in parks, or the Champs Elysées in Paris, although

in the 1840s they were becoming more formalized and were being held

in renovated or purpose-built halls during the winter months. Philippe

Musard had won popularity for his promenade concerts in Paris in

1833, and a few years later they were being imitated in London—an in-

debtedness highlighted by the phrase “à la Musard” tacked onto adver-

tisements. The Lyceum hosted the first in 1838, with its seats boarded

over to accommodate a standing audience.

13

The next year, in one of

the earliest references to music being “light,” the editor of the Musical

World, noting the hundreds attracted to the Lyceum Promenade Con-

certs, remarks: “when we contemplate the gratification that the lighter

music seems to afford to a very large portion of the audience, it appears

selfish to sneer at the means that produced it.”

14

The programs con-

sisted of overtures, quadrilles, solos, and waltzes by Joseph Lanner and

Strauss Sr. At Drury Lane in 1840, “Concerts d’été” were announced,

and Louis Jullien, who had fled from France to London because of in-

New Markets for Cultural Goods 41