Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

she conducts with her bow, and acts as leader alternately. Her conducting

is not conducting in the Richterian sense: there is no reason to suppose

that she could use a bâton, so as to produce an original interpretation of a

classical work; but she marks time in the boldest and gayest Austrian spirit,

and makes the dances and marches spin along irresistibly.

39

The ladies’ orchestras (Damenkapellen) that were formed in Austria

and Germany in the mid–nineteenth century were mainly involved

in playing Unterhaltungsmusik (overtures, marches, dances, character

pieces), and their members were typically of lower-middle-class origin,

many drawn from families of musicians. These orchestras would usu-

ally play at leisure resorts (like spas) and in public gardens, parks, and

hotel restaurants. Their size was extremely varied, and might be any-

thing from four to sixty strong.

40

The standard of playing was generally

considered to be high. The Vienna Ladies’ Orchestra had been going for

many years, and had already toured New York in 1871.

The first British ladies’ orchestras were amateur—the Dundee

Ladies’ String Orchestra and Lady Radnor’s Orchestra—but that was

soon to change. Much praise was given to the orchestra put together

for professional engagements in England by Mrs. Hunt. One critic re-

marks, “Those who have had an opportunity of hearing Mrs. Hunt’s ca-

pable orchestra will appreciate the fact that it is quite possible to bring

together a body of lady orchestral performers who will play pieces

suited to string and wood-wind instruments at least as well as musi-

cians drawn from the other sex.”

41

Mrs. Hunt, the conductor, had ear-

lier experience as a piano soloist. She then formed a band, initially

twelve strong, with the help of John Ulrich, and performed for the first

time at the house of Captain Barron in Grosvenor Square, on which oc-

casion Arthur Sullivan was present. Perhaps through Sullivan’s inter-

cession, W. S. Gilbert designed their costumes after the style associated

with a French women’s club of the seventeenth century called Les Mer-

veilleuses, but as the orchestra obtained more and more engagements,

the players also appeared in military costume as Les Militaires if the

type of engagement seemed to warrant it (see fig. 1.1). Rosabel Wat-

son, who formed the Aeolian Ladies’ Orchestra, thought the costumes

worn by Mrs. Hunt’s Orchestra (in which she had performed) under-

mined the professional status of women musicians.

42

She may well

have taken note of the kind of patronizing comments made by concert

reviewers such as Shaw.

Mrs. Hunt’s Orchestra performed at aristocratic country homes, as

well as at venues in London (including several months at the Waterloo

Panorama). They then embarked on a tour, which took in Scotland and

Ireland. They also toured abroad, playing at the Paris Exhibition and

the Nice Municipal Casino. On tour, the orchestra consisted normally

of thirty players. Like the Viennese Ladies’ Orchestra, they frequently

included some men in their ranks, since heavy brass instruments were

not commonly played by women—though Mrs. Hunt, herself, saw no

22 Sounds of the Metropolis

reason why they should not be. Women brass players were certainly to

be found in Salvation Army bands, since William Booth had a policy of

sexual equality, and these players would have been visible at his Crys-

tal Palace music festivals (begun 1890), which attracted many thou-

sands.

43

The biggest difficulty for Mrs. Hunt, however, was not in find-

ing suitable women players but in finding continuous engagements; so

by 1897, the control of her orchestra had passed into the hands of a

limited company. By that time, there was little doubt that women were

beginning to see possibilities of making careers as professional instru-

mental musicians, and a Strand Musical Magazine article on Mrs. Hunt

concludes, “there are certainly professions open to women which are

not only less lucrative, but generally offer less advantages than that of

an orchestral musician.”

44

Women were already playing in a mixed-sex

orchestra at the triennial Handel Festival at the Crystal Palace in the

1890s.

45

Nevertheless, despite their growing numbers, they were still

facing prejudice and exclusion, and were not permitted membership in

the London Orchestral Association. The professional mixed orchestra

was finally assured when Henry Wood gave positions to six women in

the Queen’s Hall Orchestra in 1913 on equal pay terms with the men.

Wood remarks that the men, in fact, “took kindly to the innovation.”

46

Not every city in this survey responded to social change so promptly:

despite those pioneering “Vienna Ladies,” women were not allowed to

audition for the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (founded, as men-

tioned earlier, in 1842) until 1997.

47

Professionalism and Commercialism 23

Figure 1.1 Mrs. Hunt’s orchestra in 1897.

Prices were said to be “within the reach of everyone” at the first

Queen’s Hall promenade concert, the promenade itself being a shil-

ling;

48

however, as we have seen from Ria’s story, for the same price you

could have a very good seat in a music hall. “Cheap” depends heavily

on context, the venue, and its location. Victoria Cooper has provided a

carefully considered analysis, drawing on a variety of sources, of the

amount of disposable income, as well as leisure time, that was available

for people in different occupations to spend on musical activities. At the

less prosperous end of the market, a budget of between 1 and 2 percent

of income “would permit the purchase of one Novello score per year in

addition to limited attendance at concerts” for a schoolmaster earning

£81 a year in 1851.

49

This is below the income of £150 a year that Geof-

frey Best set as the threshold for membership in the middle class.

50

The Sheet Music Trade

Alongside the promotion of public performances, music publishing was

the most important musical money-making enterprise of the new com-

mercial age. The commodification of music was at its most visible in the

sheet music trade, and the purchase of sheet music was an unambigu-

ous and conspicuous example of the consumption of musical goods.

After 1775, Vienna became an important center for engraved music,

stimulated by the presence there of composers such as Haydn and

Mozart. Music engraved on copper plates was the normal method of

printing when the Austrian Aloys Senefelder sought a cheaper method

in lithography. At first he worked with etched stone, but in 1797 he in-

vented a new lithographic method in which he no longer etched away

at the stone surface but instead relied on chemical reactions, especially

the mutually repelling qualities of grease and water. From the town of

Offenbach, lithography spread via the music publisher André’s family

connections to London and Paris. Senefelder himself was responsible

for its introduction in Vienna, where in the early years of the nine-

teenth century he founded the press Chemische Druckerei.

51

The ear-

liest Viennese examples are not of a quality to compare with engraved

music, and the same goes for the Imprimerie lithographique in Paris.

Lithography in London was mainly used for pictorial work before mid-

century, and gave a boost to the sheet music trade because of the in-

creased facility of including illustrations. Some of those responsible for

pictorial chromolithographic title pages in the 1860s, like Alfred Con-

canen (mainly music hall songs) and John Brandard (mostly dance

music), created work of high quality. In 1843, the sons of Senefelder’s

partner in the lithographic trade moved to New York.

52

Two rival technologies to lithography, engraving (which had

switched to the use of pewter plate) and moveable music type, contin-

ued to be used into the 1860s. In the 1840s, when Novello opted for

musical type, most music was being engraved on pewter plates, which

24 Sounds of the Metropolis

was a cheaper option if small numbers were required. The problem was

that the plates wore out, sometimes after only a thousand impressions.

Music types were expensive to purchase, and a lot of time was taken

setting them in place, but they proved cheaper if sales ran into several

thousands rather than several hundreds. Spina in Vienna needed to

have a hundred plates made to satisfy demand for Johann Strauss Jr.’s

Blue Danube waltz (see chapter 5), even though each plate was deemed

sufficient for 10,000 copies.

53

Though some publishers were committed

to the cleaner look of engraved music, the replacement of lithographic

stone by zinc and aluminum plates and the use of the rotary press made

lithography an ever more attractive option. Powerful lithographic ma-

chines in the 1850s could produce prints at fifty times the rate of hand

presses (3,000 impressions an hour instead of 60).

54

A number of song

publishers used color lithography for title pages in London and New

York, and it was very popular in the 1890s.

Boston, then Philadelphia, had taken the lead in music publishing

in the United States, but New York soon began to thrive as a center of

sheet music and piano production in the nineteenth century. Firth and

Hall began publishing music in New York in 1827, and became one of

the biggest firms within a decade; their publication of Henry Russell’s

“Woodman, Spare That Tree!” (1837) set the seal on this. They had al-

ready become a piano business by then, having linked up with piano

maker Sylvanus Pond. Hall broke with the other partners in 1847 to

form Hall and Son. The business paper the New York Musical Review

named Firth and Pond, Hall and Son, Horace Waters, and Berry and

Gordon as the biggest publishers in New York in 1855—the turnover of

music books and sheet music at Firth and Pond alone was worth

$70,000 that year. This firm’s sales of pianos were worth $50,000, and

other instruments added a further $30,000. At that time, they em-

ployed ninety-two people, forty of whom were in the piano factory

(soon to double in numbers).

55

Firth published Stephen Foster’s songs,

the biggest hit among them being “Old Folks at Home,” with 130,000

copies sold between 1851 and 1854.

56

Novello opened a New York

branch in 1852, having already captured the market there with the

firm’s cheap oratorio editions and collections of sacred music. However,

prevalent piracy and ineffective copyright legislation meant that popu-

lar song publishers remained fixed in their respective countries.

Before the Civil War, the biggest American music publisher was

Oliver Ditson of Boston (who was also a silent partner of Berry and

Gordon in New York). The massive sales of certain Civil War songs (for

instance, George Root’s “Tramp, Tramp, Tramp”) seemed stimulated by

the exceptionally emotional times, but the music trade continued to

boom in the next decade. This was helped by the simultaneous boom

in music education, especially piano lessons. Census figures are not

available till 1900, but then show 92,000 full-time music teachers and

musicians (compared to 43,249 in Britain).

57

Ditson remained Ameri-

Professionalism and Commercialism 25

ca’s biggest popular song publisher until the 1880s. New York’s biggest

firms in this decade were Harms (established 1881) and Witmark (es-

tablished 1885). The huge economic potential of popular music was ev-

ident in the 1890s when Charles Harris’s “After the Ball” (1892) dem-

onstrated that a hit song could sell millions of copies. When Witmark

moved to 49–51 West Twenty-eighth Street in 1893, it signaled a shift

of the center of music publishing from the theater district around Union

Square to what was to become known as Tin Pan Alley (a term suppos-

edly coined by songwriter Monroe Rosenfeld). There was a new atti-

tude to marketing, along with new strategies for promoting songs.

58

Song-plugging, for example, involved performances in music shops

and department stores to boost sales. In a development of the Boosey

Ballad Concert practice of paying singers royalties on performances,

New York publisher Woodward began paying singers to promote songs.

Witmark introduced the professional copy, giving it free of charge to

professional singers.

59

The song itself had to have a “punch”—some-

thing to make it stand out in a competitive market, like a memorable

group of notes, or a memorable line in the lyric.

60

Other promotional

devices included advance copies and free theater band arrangements.

On the downside, prices were being cut (10–15 cents rather than 25

cents) and a song was beginning to have shorter life span—a popular

success might be forgotten after three months. However, the arrival of

attractive new syncopated styles kept the market buoyant toward the

end of the century.

In London, Novello made successive reductions in the price of

music, and cheap music was also to be had from Charles Sheard (the

Musical Bouquet series), Davidson, and Hopwood and Crew. By the end

of the century, a popular song in Britain would frequently sell 200,000

copies. There were bigger hits, such as “The Lost Chord,” which sold

half a million copies between its first publication (1877) and 1902.

61

In 1898, the Musical Opinion estimated the annual sales of sheet music

in Britain at around 20 million,

62

higher than the equivalent in Aus-

tria or France, though not the United States. The major reason for this

was that the eagerness to possess a piano was greater in Britain and

America.

In the competitive business of music publishing, compromises were

often necessary. There were, for example, perils attached to trying to

obtain an exclusive contract with a composer, as the Paris agent of

Breitkopf and Härtel explains to a colleague in a letter of 1837:

Your method of buying everything by one composer is not going to work,

considering that it leads to the present competition and [the resulting] in-

flation. Sometimes we should let others have the less important pieces,

whatever suits their business. [If we did that], the others would let us have

some good things and not invade my territory. Schott and Schlesinger are

my tough competitors who are often much faster and more generous than

I dare to be.

63

26 Sounds of the Metropolis

He then tells how, in the next month, Schott outbid him for Thal-

berg’s piano fantasies on “God Save the Queen” and “Rule Britannia.”

64

Sometimes it was a case of backing the wrong horse. Both Joseph

Mainzer and John Hullah were champions of fixed-do systems for sight

singing. Hullah basing his system on that used for the Orphéon choirs

in Paris, but the Rev. John Curwen’s moveable-do system of Tonic Sol-

fa won the day in Britain.

The well-documented dealings of the firm of Novello are an illus-

tration of the variety of business decisions that nineteenth-century

music publishers had to make. Vincent Novello, an organist, set up his

business at his home in Oxford Street in 1811 when he failed to find a

publisher for a collection of sacred music he had compiled.

65

His son,

Alfred Novello, had the idea of publishing cheap editions of admired

choral works.

66

Cheap editions of oratorios like Handel’s Messiah and

Haydn’s Creation were crucial to the spread of choral societies through-

out Britain, societies that then stimulated further demand. Novello

turned next to journal production, publishing the Musical World from

1836. Music publishers were, from the beginning, naturally keen to en-

courage an interest in music and especially their own catalogues. Breit-

kopf and Härtel began publication of the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung

in 1798 in Leipzig, and it allowed them to advertise and promote their

trade.

67

Maurice Schlesinger, who was speculating in railway stocks

when he was not engaged in music publishing matters, founded the

Gazette musicale to promote his wares. He then took over François-

Joseph Fétis’s more earnest Revue musicale de Paris, and created the

Revue et Gazette musicale, catering for the musical tastes and aspirations

of the bourgeoisie.

68

In the second half of the century, literature about

music increased significantly—eighty-three different music periodicals

appeared in New York between 1850 and 1900

69

—and music publish-

ers often started their own journals.

70

The great success of Joseph Mainzer’s singing classes in the early

1840s led Alfred Novello to take over Mainzer’s periodical, which from

June 1844 became the Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, priced at

a penny halfpenny. Difficulties in getting the octavo-size publication

printed encouraged him to go into printing himself in 1847, using the

method of moveable musical type that William Clowes had recently

improved on for the periodical the Harmonicon (1823–33). This meant

that Novello could now publish for other firms. Henry Littleton, who

had been Alfred’s assistant, took over when he retired in 1857, and

eventually bought up the business in 1866. The next year, Littleton

bought up the firm of Ewer, primarily to acquire the British copyright

of Ewer’s Mendelssohn publications, especially the oratorio Elijah. He

began promoting oratorio concerts in 1869, ensuring that ticket prices

offered the same value for money as his publications, so that he was

able to stimulate demand further and ensure that the firm became “one

of the largest of its kind in the world.”

71

Professionalism and Commercialism 27

The Piano Trade

Though choral singing was certainly important to the sheet music

trade (for instance, two flourishing sacred music societies merged in

1849 to form the New York Harmonic Society), most publishers were

concerned above all with music for piano. Some businesses yoked the

sheet music trade and the piano trade together: when Mr. Firth of Firth

and Hall, New York, died in September 1864, he was declared “the old-

est and probably the best known music publisher and piano dealer in

the States.”

72

Piano music—particularly dances, operatic excerpts, and

songs—formed the largest and most profitable area of music publish-

ing. In Vienna, it was already an established fact in the early 1800s that

waltzes for piano “were among the publishers’ safest aids to staying in

business, and they disliked to be short of them.”

73

For the prolific pro-

duction of piano music based on operas, nobody beat the Viennese

composer Carl Czerny. With the increased sales of pianos as the century

wore on came a demand for music that sounded difficult without actu-

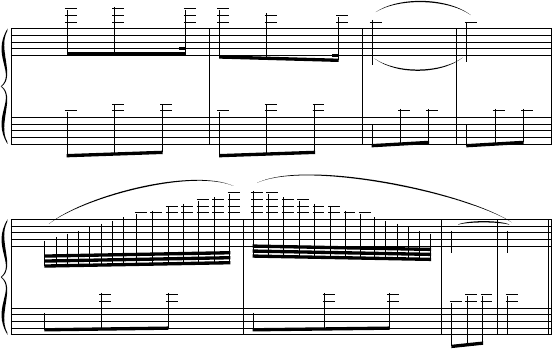

ally being so. An example from later in the century that remained a

drawing room favorite into the twentieth century is J. W. Turner’s Fairy

Wedding Waltz (1875), which allows the fastest of scale passages to be

accomplished easily as a glissando by means of a right-hand fingernail

(see ex. 1.1).

In the 1790s, a piano was a fashionable luxury in wealthy Viennese

homes. The English piano was substantially different from the Vien-

nese piano in the eighteenth century; it was a heavier instrument with

thicker strings and soundboard, and a more complex action.

74

Conrad

Graf was the important Viennese maker, and his pianos still sounded

28 Sounds of the Metropolis

&

?

8

3

8

3

œ

œ

f

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

&

?

œ

glissando

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

15

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

14

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

‰

œ

œ

œ

‰

Example 1.1 J. W. Turner, The Fairy Wedding Waltz (London, 1875),

measures 9–16.

different from English models in the 1820s. John Broadwood was the

most significant figure in the technological development of the English

piano, and London became a center of piano making. The new work-

ing relations of the Industrial Revolution were brought to the produc-

tion of pianos when Broadwood introduced a division of labor to in-

crease efficiency and lower costs.

75

Matthias Müller in Vienna and John Hawkins in Philadelphia, both

around 1800, had made early versions of the upright piano (with strings

stretching downward to the floor inside the cabinet). The population

living within the Vienna’s city walls was, for the most part, dwelling in

houses divided into apartments; space was at a premium, so a market

for upright pianos opened up. Erard was the first firm in Paris to iden-

tify the market for pianos for apartment-dwellers, and set about design-

ing an upright model in the 1820s that would fit a smaller room.

76

Up-

rights were to become the norm for smaller homes in Paris, London,

and Vienna—but not New York, where square pianos remained in

vogue longer. In London, a six-octave Broadwood cottage piano in

1828 cost 50 guineas, exactly half the price of the firm’s horizontal

grand.

77

A new cottage piano could be had from Robert Wornum (Bed-

ford Square), who had patented his upright design in 1826, for 42

guineas in 1838.

78

Uprights and squares were domesticated pianos, just

as reed organs were domesticated organs. American organs, which

sucked through the reeds, were thought to produce a steadier tone

than French harmoniums, which blew through the reeds, and they be-

came popular during the second half of the century.

79

In 1843, Henri Heine complained of the impossibility of escaping

the piano in Paris: “you can hear it ring in every house, in every com-

pany, both day and night.”

80

While this is humorous hyperbole, it is not

far wide of the mark: the Gazette of 10 November 1845 estimated the

number of pianos in Paris at 60,000.

81

In the same year, there were 108

piano makers in Vienna, but these were small businesses, and Viennese

pianos were usually cheaper and not of a high quality at this time.

82

Taste in piano tone had certainly changed by the time of the Great Ex-

hibition of London in 1851. Of the ten countries exhibiting pianos, only

makers from Austria and Canada received neither a prize nor an “hon-

orable mention.”

83

Austria reestablished its reputation soon afterward,

especially with the admired pianos made by Bösendorfer in Vienna. In

1851, there were around 200 English piano firms, most of them located

in London, and Broadwood still dominated, with Collard in second

place. William Pole, in his catalogue Musical Instruments in the Great In-

dustrial Exhibition of 1851, claimed that a million pounds worth of pianos

had been made that year, while France in 1849 produced £320,000

worth.

84

The number of men playing pianos should not be regarded as

insignificant: there was barely a piano in Oxford colleges in the 1820s,

and there were an estimated 125 pianos and 30 concertinas by the mid-

1850s.

85

$15 million (representing 25,000 instruments) was spent on

Professionalism and Commercialism 29

pianos in the United States in 1866.

86

Steinway and Sons (the name

was originally Steinweg) opened in New York in 1853 on East Four-

teenth Street and soon became the preeminent American maker. Stein-

way’s overstringing, which was perfected in 1859, was a key ingredient

in the firm’s success. The gold medals awarded to the firms Steinway

and Chickering at the Paris Exhibition of 1867 sealed the United States’

reputation in the European piano market, and by 1880 Steinway was

one of the world’s leading brands.

The association of domestic piano playing with young middle-class

women had become ubiquitous by the mid–nineteenth century.

87

Piano

playing and singing were considered important genteel accomplish-

ments for young middle-class women. It was regarded as indicative of

moral and aesthetic refinement, and not of any desire to perform pro-

fessionally. Because women not only played the piano but were also

the chief users of another item of modern technology, the sewing ma-

chine, an unusual business opportunity arose. Some American firms

after the Civil War tried to cope with the demand for both, and for a

while there was even a periodical called the Musical and Sewing Machine

Gazette.

88

The fact that middle-class girls were obliged to learn the piano

does not alone explain what Cyril Ehrlich calls the “piano mania” of

late nineteenth-century Britain.

89

Prices of musical instruments were

falling in the second half of the century. Pianos became available to a

wider social mix, not only because of the drop in price but also because

a three-year installment plan (hire purchase) was introduced in Lon-

don and New York. This system had arisen in London in the 1860s, at

first mainly for inferior instruments, and available only to customers

with permanent employment. It became more flexible in the 1870s and

helped make possible the large-scale acquisition of pianos. Pianos “for

the million” were being advertised at 10 guineas in 1884.

90

On top of

this, there was a growing market in secondhand instruments. The price

of sheet music also fell in the 1870s, as the volume of production and

number of competing firms increased. In the United Kingdom, the re-

moval of excise duty on paper in 1861 also contributed to lowering

prices.

91

Instrument technology was developing throughout the cen-

tury, and not only where pianos were concerned: J. P. Oates’s new pis-

ton valves for brass were on show at the Great Exhibition of 1851, as

were Adolphe Sax’s sax horns and saxophones.

Some piano firms built their own concert halls. In midcentury,

Pleyel had two halls in Paris suitable for concerts, and Erard also had a

hall with an auditorium. Pleyel and Erard were the biggest firms in

Paris. The Bösendorfer-Saal, a recital room holding 500, opened in

1872 in Vienna; five years later Bösendorfer’s main rival opened the

Saal Ehrbar, seating the same number. In 1866, Steinway built a con-

cert hall in New York to hold 2,500, and opened a hall adjoining their

London branch in 1878 (capacity 400). Music publishers also had a

similar interest: Tom Chappell of the firm of that name largely financed

30 Sounds of the Metropolis

the building of St. James’s Hall. The Viennese pianist Henri Herz pro-

vides an example of how to seize opportunities and show business ver-

satility in the first half of the century. He first earned money as a virtu-

oso in Paris, then as a piano teacher and composer of piano music of

seeming difficulty, and then as a piano maker. Muzio Clementi, re-

nowned for his piano compositions, went similarly into business as a

piano maker in London.

The size and weight of pianos meant that the import and export

market was not huge, though German pianos became increasingly pop-

ular in Britain after 1875, and Queen Victoria bought a Bechstein grand

in 1881.

92

Bechstein (established 1853 in Berlin) were overstrung, like

Steinway, and adopted the iron frame. English firms had been suspi-

cious of this technology, thinking the tone inferior—an impression that

can, perhaps, be put down to the romanticizing of wood in a country

of metal industries. Steinway was heavily into sales promotion, and en-

gaged Anton Rubinstein to tour America publicizing their business in

1872–73.

93

They also sought testimonials from eminent musicians in

Europe to be quoted in their advertisements. Steinway certainly ex-

ceeded other firms in the “hard sell” tactics they employed, though the

quality of their instruments was beyond question.

94

It must have been

astonishing for musicians born early in the century to see America

achieve the position of being the world’s largest producer of musical in-

struments.

95

Copyright and Performing Rights

For Raymond Williams, copyright and royalty are the two significant

indicators of the changed relations that professionalization and the cap-

italist market for cultural goods brought about.

96

The enforcement of

copyright protection on the reproduction and performance of music

was an enormous stimulus to the music market, affecting writers, per-

formers, and publishers. In Britain, the Copyright Act of 1842 allowed

the author to sell copyright and performing rights together or sepa-

rately. In France, protection was offered to café-concert songwriters for

the first time after a court action for an unauthorized performance in

Paris in 1847. Jacques Attali maintains that the French law acknowl-

edging a performing right in songs could not have come to pass with-

out the existence of cafés-concerts.

97

It was there that songs were rec-

ognizably commodities for consumption and, thus, had a claim to be

considered “works” alongside those already protected in the law of

1791. The reaction in La France Musicale was one of disbelief: “If you

create operas, symphonies, in a word, works that make a mark, then

royalties shall be yours; but taxing light songs and ballads, that is the

height of absurdity!”

98

In 1851, however, Société des Auteurs, Com-

positeurs, et Editeurs de Musique was founded (SACEM ) and became

active in collecting performing rights and pursuing infringements. Aus-

Professionalism and Commercialism 31