Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

For the middle class, culture was instructive but first required that

people were instructed in it; hence the didactic character of attempts to

encourage working-class “appreciation.” The People’s Concert Society,

founded in 1878, was an amateur organization dedicated to making

high-status music known among the London poor. The society began

Sunday concerts of chamber music in South Place, Moorgate, in 1887.

From the succeeding year, admission was free, or a voluntary contribu-

tion could be made, and attendance was good.

24

In 1882, the Popular

Musical Union was founded “for the musical training and recreation of

the ‘industrial classes.’”

25

Concerts took place at the People’s Palace in

London’s East End, and continued to do so until 1935. Persuasion was

used, but no coercion was needed to interest the working class in music;

the ideology of respectability and improvement meant that music, in-

strumental as well as vocal, could even be found on the timetables of

instructive activities at Mechanics’ Institutes, especially after 1830.

26

The British brass band movement, in the second half of the century,

was viewed, alongside choral singing, as another example of “rational

and refined amusement,” hence the willingness of factory owners to

sponsor works bands.

27

They were to feel sour, however, when they dis-

covered brass bands leading marches of striking workers.

28

These bands

had their roots in the industrial North, but the steel, ironworks, and

shipping companies of East London also had bands in the 1860s. Huge

annual contests were held at the Crystal Palace during 1860–63. The

first of these, a two-day event, attracted an audience of 29,000.

29

The

test pieces for the contests at the Crystal Palace placed an emphasis on

high-status music: selections from Meyerbeer’s grand operas were the

favorite choices, as at the Belle Vue contests in Manchester during the

same decade. In the other cities of this study, regimental bands were a

common sight. Paris’s most famous military band was that of the Garde

Republicaine (formed in 1854 as the band of what was then the Garde

de Paris). It acquired a substantial reputation in America while on tour

there in the early 1870s. Adolphe Sax was responsible for the instru-

mental organization of the band. It contained several families of instru-

ments with six pistons (trumpets, trombones, saxhorns, and tubas) that

were of his own invention, his desire being to enable a more consistent

production of chromatic runs of notes than that possible on three-pis-

ton instruments.

30

In other respects, the band was not dissimilar in size

or instrumentation from that of the Household Brigade in London. In

the 1850s, the sale of refreshments was permitted on Sundays in certain

London parks to coincide with military band performances. This met

with strong opposition from those who wished to guard Sunday’s im-

portance as a religious day and who feared also that the excitement of

listening to band music would trigger civil disturbance.

31

On the other

hand, the right kind of music, in the right surroundings, was thought to

act as “a civilising influence to which the lower classes were particularly

62 Sounds of the Metropolis

responsive.”

32

In Vienna, at midcentury, a license from the magistracy

was required for permission to make “music for entertainment in pub-

lic resorts,” and the intention to include concert and operatic music

alongside dance music was a great help in obtaining it.

33

Physical Threats to Morality

A belief in the moral power of music was an all-pervasive ideology: “Let

no one,” the great champion of the improving powers of music the

Reverend Haweis admonished, “say the moral effects of music are small

or insignificant.”

34

It was the activities that accompanied music making

that raised suspicion of unwholesome conduct, not the music itself.

Even in Vienna, for example, there were those who worried about the

moral propriety of the waltz, its sensuality, and the close proximity of

the couple dancing.

35

The waltz offers an example of how music could

be perceived as being linked to a physical threat to public morality.

When the waltz first began to be danced “in society,” it provoked moral

outrage in some quarters. Existing society dances were more decorous;

the minuet and gavotte may have been dances for couples, but they

emphasized graceful movement and involved delicate contact with the

fingers only. In the waltz you could hold your partner, and not just

with fingertips. Certainly, it was de rigueur for both men and women to

wear gloves, but you could still hold your partner close. There were

other subversive features, too, as Arthur Loesser explains with refer-

ence to the early waltz of the 1790s:

it seemed utterly disorderly—it had no fixed number of steps, no pre-

scribed direction of movement, no general pattern. It was for no settled

number of couples: each pair danced without caring about any of the oth-

ers—any couple could enter the dance or leave it at any second, as the

whim might strike them. Truly, the waltz was an illustration of the two

most intoxicating virtue-words of the age: the “people” and “liberty.”

36

The Empire line dominated women’s fashions when the waltz was first

introduced, and ball gowns allowed libidinous males considerable op-

portunity for groping, especially given the absence of corseting. Clothes

were soon designed to place much more textile between partners, the

outcome being the bell-shaped dress. Next, the development of the

crinoline meant that heavy underwear was no longer necessary—

though it is often forgotten that the cage collapsed as the man pushed

forward.

Byron wrote a poem on the waltz in 1812 when it was little known

in England. The following excerpts illustrate his (perhaps surprising)

moral disgust:

From where the garb just leaves the bosom free,

That spot where hearts were once supposed to be;

Music, Morals, and Social Order 63

Round all the confines of the yielded waist,

The strangest hand may wander undisplaced;

The lady’s in return may grasp as much

As princely paunches offer to her touch.

Hot from the hands promiscuously applied,

Round the slight waist, or down the glowing side,

Where were the rapture then to clasp the form

From this lewd grasp and lawless contact warm?

At once love’s most endearing thought resign,

To press the hand so press’d by none but thine;

To gaze upon that eye which never met

Another’s ardent look without regret;

Approach the lip which all, without restraint,

Come near enough—if not to touch—to taint.

37

The waltz combined closeness with a sensation of the room spin-

ning around, and this could prove an erotic and giddy experience. Later

in the century, this is what Madame Bovary discovers when she waltzes

for the first time (the experience being heightened by her consumption

of alcohol):

They began slowly, and then went faster. They turned: everything around

them turned—the lamps, the furniture, the wainscoting, and the floor, like

a disc on a pivot. On passing near the doors, the hem of Emma’s dress

grazed

38

his trousers. Their legs entwined; he looked down at her, she

looked up at him; a languor took hold of her; she stopped. They set off

again; and, with a more rapid movement, the Viscount, dragging her, dis-

appeared with her to the end of the gallery, where, panting, she nearly fell,

and, for a moment, leant her head on his breast. And then, still turning,

but more gently, he conducted her back to her seat; she leaned back

against the wall and put her hand over her eyes.

39

Queen Victoria’s interest in waltzing helped to win it respectability

in Britain, but moral concerns about dance music did not disappear,

and were always ready to resurface.

40

They did so, for instance, in 1885,

when Mr. Burnand of the Aberdeen Presbytery launched a widely re-

ported attack on “balls, dancing parties, and promiscuous gatherings of

people of both sexes for indulging in springs and flings and artistic

circles and close-bosomed whirlings.”

41

Ironically, it was not the waltz

but the galop that ended up being banned in Vienna, after the authori-

ties decided it was injurious to health in the 1840s. Strauss Jr.’s way

around this was to develop the Schnell-Polka, which was more or less

the galop under a new name. In 1854, when he produced his Schnell-

post-Polka (Express Mail Polka, op. 159), a cholera epidemic was creat-

ing a more distracting health worry than that of purportedly dangerous

dances.

64 Sounds of the Metropolis

Public and Private Morality

It was meaningless, of course, if the entertainment was respectable but

the venue not. Concern about prostitution in theaters and music halls

grew in the second half of the century.

42

In Vienna, prostitutes were

found at some of the grandest dance halls, such as the Apollo in the

1820s.

43

The next decade the Apollo cleaned itself up entirely—by be-

coming a soap factory. In Paris, concern about prostitution in cafés de-

veloped in the 1860s, previous attention having been on other public

spaces, such as boulevards and gardens. Alcohol consumption was an-

other threat to morals and respectability, and fractional interests within

the bourgeoisie used music as a medium of persuasion; for example, the

temperance groups in London and New York promoted songs portray-

ing the destructive effects of drunkenness on the home and family.

44

The music hall was especially disliked, not just because of the availabil-

ity of alcohol there but also because it was celebrated in song (hence at-

tempts to create “coffee music halls”). At one social level were Bessie

Bellwood calling for her pint of stout and Gus Elen yearning constantly

for half pints of ale, and at another were George Leybourne and Alfred

Vance praising, respectively, champagne from Moët and from Cliquot.

45

Music for the nineteenth-century middle-class home aligns itself

with one of the fundamental “Victorian values”—that of improvement.

It was the possession of an improving or edifying quality that allowed

music to be described, in a favorite Victorian phrase, as “rational amuse-

ment.” The quality that makes the nineteenth-century domestic ballad

distinctive arises from its moral concerns and not from sentimental self-

indulgence or a love of the maudlin, as some people mistakenly sup-

pose. In short, American and British ballad writers and composers were

often concerned to place sentimentality in the service of other aims,

and these other aims were primarily social, moral, religious, and polit-

ical rather than aesthetic.

The moral tone, whether we regard it now as healthy or not, is pre-

cisely what makes the Victorian ballad differ in character from the

songs that came after. Early twentieth-century British and American

ballads tend to shy away from the moral didacticism found in the pre-

vious century’s ballads. The two closing decades of the nineteenth cen-

tury were a transitional period, during which the variety of ballad types

and ballad forms decreased. The structural diversity illustrated by songs

like “Come into the Garden, Maud” (words by Alfred Tennyson, music

by Michael Balfe, 1857) and “The Lost Chord” (words by Adelaide

Procter, music by Arthur Sullivan, 1877) gives way to the more pre-

dictable shapes of post-1880 ballads, in which irregularities are accom-

modated to a more obvious overall verse and refrain form. This process

was accelerated by the song sheet production of the group of firms in

New York’s Tin Pan Alley in the 1890s.

Music, Morals, and Social Order 65

So let us begin by asking what themes were found suitable for the

purpose of improvement. There are many songs that remind us of our

own mortality, or place human life in a grander scheme of things, or

contrast the secular and the divine. These, it should be stressed, do not

always need to have an overtly sacred theme. There are other songs that

take children as a theme, perhaps celebrating the love of parents for

children, or touching on infant death, or presenting illustrations of the

presumed innocence of children as a means of teaching adults a moral

lesson. In addition to these, there are songs that deal with friendship,

pride in one’s country, and courage, whether that is exemplified in

battle or in facing the grim realization that one has been jilted in love.

46

The features that give the nineteenth-century domestic ballad its

distinctiveness spring from a desire to teach a moral lesson, or educate

people about appropriate social behavior, or edify and uplift them spir-

itually and drive them on to perform good deeds. Perhaps the first song

that established firmly the kind of sentiment that was to be emulated

by all songwriters who saw the middle-class home as their market was

“Home, Sweet Home!” of 1823. Even at the end of the century, it was

still felt to possess a remarkable moral and emotional power. In one

story of an English colonial boy in the Australian outback, it is thanks

to his pet bird being able to whistle “Home, Sweet Home” that he is

saved from a gang of desperados: “strange and marvelous it was to see

the tears trickling down the cheeks of these grizzled scoundrels at the

thought of the homes into which they had probably brought nothing

but shame and misery.”

47

The song was, interestingly, a collaboration

between an American, John Howard Payne, and an Englishman, Henry

Bishop. In that, it foreshadowed the transatlantic traffic in this type of

song that grew with every decade of the century. It featured in the En-

glish opera Clari, or The Maid of Milan, and it has an Italianate character

suited to the opera’s subject. However, the Italian connection is no

more than that of a cantabile operatic style, rather than an Italian folk-

song, despite the fact that Bishop had tried earlier to pass it off as a Si-

cilian air in a book of national airs.

48

The Italianate quality persisted in many of the songs composed by

the Jewish English entertainer Henry Russell (fig. 3.1).

49

One such was

“Woodman, Spare That Tree!” of 1837, another Anglo-American cre-

ation, with words by George Pope Morris.

50

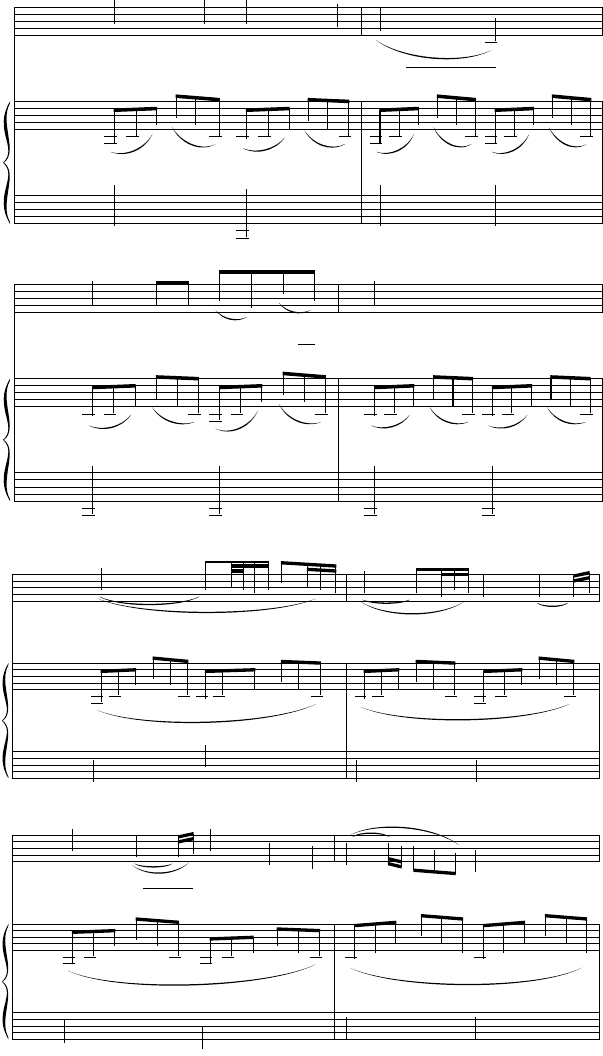

A few sample measures

will show that this is not a million miles from the famous aria “Casta

diva” from Bellini’s Norma of 1831 (see ex. 3.1).

This song brings us face to face more directly than does “Home,

Sweet Home” with what some find the biggest obstacle to taking nine-

teenth-century ballads seriously: what is perceived as exaggerated sen-

timentality. Here is a narrative concerning someone whose emotional

ties to a particular old oak are likely to seem excessive even to the most

ardent tree-hugging hippie. However, Henry Russell is quite clear on

this point: “sickening sentiment is born of a sickening mind,” he pro-

66 Sounds of the Metropolis

claims, believing that his own songs, in contrast, exemplify a healthy

moral tone.

51

Edgar Allan Poe was a champion of George Morris, claim-

ing that “Woodman, Spare That Tree” was a composition “of which any

poet, living or dead, might justly be proud.” Poe was convinced it would

make Morris’s name immortal.

52

The sternest moral fiber is to be found in temperance songs, al-

though these frequently sounded too haranguing even for those who

otherwise prided themselves on their respectability. All the same, 500

people were reputedly turned away from a concert in Niblo’s Garden

given by the teetotal Hutchinson Family.

53

Where alcohol was con-

cerned, the middle-class watchword tended to be moderation, not pro-

hibition. The most affecting type of temperance song overcame this re-

sistance by putting its message in the mouth of a child—for example,

“Come Home, Father!” (words and music by Henry Clay Work, 1864)

and “Father’s a Drunkard and Mother Is Dead” (words by Stella, music

by Mrs. E. A. Parkhurst, 1866). The first of these bears the epigraph

54

’Tis the SONG OF LITTLE MARY,

Standing at the bar-room door

While the shameful midnight revel

Rages wildly as before.

The laboring poor may have been sung about and even felt to be

understood in certain socially concerned drawing room ballads, but

their lives often lay outside the experience of those who sang them (see

fig. 3.2). Antoinette Sterling, who so movingly performed “Three Fish-

ers Went Sailing,” confessed that not only had she no experience of

storms at sea but “had never even seen fishermen.”

55

The subject posi-

Music, Morals, and Social Order 67

Figure 3.1 One of New York and

London’s most popular socially

committed and wholesome enter-

tainers, Henry Russell, in later life.

&

&

?

b

b

b

c

c

c

.

œ

j

œ

.

œ

j

œ

Wood man spare that

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

3

3

3

3

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

œ

Œ

tree!

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

˙

˙

-

&

&

?

b

b

b

œœœ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Touch not a sin gle

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

Ó

bough;

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

˙

˙

-

&

&

?

b

b

b

8

12

8

12

8

12

.

˙

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

Ca sta

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

.

‰‰Œ ‰

j

œ

.

‰‰Œ ‰

.

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

‰‰

œœ

œ

Di va, ca sta

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

.

‰‰Œ ‰

J

œ

.

‰‰Œ ‰

----- --- -

&

&

?

b

b

b

.

œ

œœ

œ

.

œ

T

œ

J

œ

Di va che i nar

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ

J

œ

.

‰‰Œ ‰

J

œ

.

‰‰Œ ‰

œœ

œœ

œ

œ

.

œŒ‰

gen ti

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

.

‰‰Œ ‰

J

œ

.

‰‰Œ ‰

- -- ---

Example 3.1 (a) Henry Russell’s “Woodman, Spare That Tree!” (words by

George Morris, music by Henry Russell); (b) “Casta diva” (Vincenzo

Bellini, Norma (1831), act 1).

(a)

(b)

68

tion such ballads addressed was that of the middle class. So, too, did the

Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas, parading middle-class prejudices, al-

beit in an ironic way, as in Ko-Ko’s list of “society offenders” in The Mi-

kado. The characters of this opera are, unmistakably, English in fancy

dress. The Gondoliers (1889) satirizes antiegalitarianism, summed up in

the lines “When every one is somebodee, / Then no one’s anybody.” It

appeared at a time of antimonarchist sentiment and the growth of so-

cialist and republican ideas. The issue of class distinction was especially

to the fore, and the Duke of Plaza-Toro lampoons the buying of titles:

Small titles and orders

For Mayors and Recorders

I get—and they’re highly delighted.

The satire aimed at the House of Lords in Iolanthe (1882) is more

plentiful than that targeting the Commons (Private Willis’s song); re-

form of the Upper House was a contemporary issue. After the first

night, a song was removed because a critic accused Gilbert of “bitterly

aggressive politics” and pathos that “smacks of anger, a passion alto-

gether out of place in a ‘fairy opera.’”

56

The song offended middle-class

values by sympathizing with a wretched pickpocket, suggesting that

anyone “robbed of all chances” would turn to theft.

The respectability of the bourgeoisie was not beyond challenge, of

course, in any of the cities that form the basis of this study. Samuel

Smiles was aware of bourgeois hypocrisy: “We keep up appearances,

too often at the expense of honesty.”

57

In Paris, Yvette Guilbert repre-

sented bourgeois vices humorously in chansons like “Le Fiacre” (words

and music by Léon Xanrof) and “Je suis pocharde!” (words by Léon

Laroche, music by Louis Byrec). When she sang at the respectable

Eden-Concert in 1890, she was allowed to sing the latter (concerning

the effects of alcohol) but not the former (concerning marital infidel-

ity). The context of “Je suis pocharde!” helped it to gain acceptability.

Guilbert herself stressed that this is a girl from a “good family” who has

been drinking champagne at her sister’s wedding and is “gentiment

grise” (slightly tipsy).

58

Pochard is both an adjective and a noun (“drunk-

ard”), and it is easy to see how offensively vulgar it might have been in

its feminine form.

The subject position of music halls and cafés-concerts was that of

the upper-working-class or lower-middle-class male. Even the large

Queen’s Music Hall, situated in solidly working-class Poplar, assumed

the audience would share the values of those social groups.

59

The per-

formers themselves were of a mixed class background: of the lions

comiques in London, for example, George Leybourne had been a me-

chanic and the Great MacDermott a bricklayer, but the Great Vance was

formerly a solicitor’s clerk. The toff or “swell” character of the 1860s ap-

pealed to socially aspiring lower-middle-class males. Leybourne, the

most acclaimed of the swells, was given a contract in 1868, at the height

Music, Morals, and Social Order 69

of his success with the song “Champagne Charlie,” requiring that he

continued his swell persona off stage.

60

The swell, however, is double-

coded: he might inscribe admiration for wealth and status, but he sub-

verts bourgeois values in celebrating excess and idleness (“A noise all

night, in bed all day and swimming in Champagne,” Charlie boasts).

Some of those attending cafés-concerts, also, were putting on appear-

ances, like the calicots (Parisian slang for drapers’ assistants, known in

London slang as “counter-jumpers”). Hence the appeal of the Parisian

swell, or gommeux, the most famous being Libert. Henriette Bépoix, a

gommeuse, appeared fast on his heels. Gommeuses were common in the

1890s, wearing extravagant feathered hats, gaudy dresses, and lots of

jewelry. They presented themselves as fun-loving and giddy, with rich,

if unattractive, lovers. The renowned twentieth-century star of the music-

hall, Mistinguett, began as an eccentric gommeuse at the Eldorado.

The efforts the bourgeoisie made in the interests of respectability

were not always an unqualified success, and sometimes failure ap-

peared unexpectedly. It would be easy to assume, given the association

70 Sounds of the Metropolis

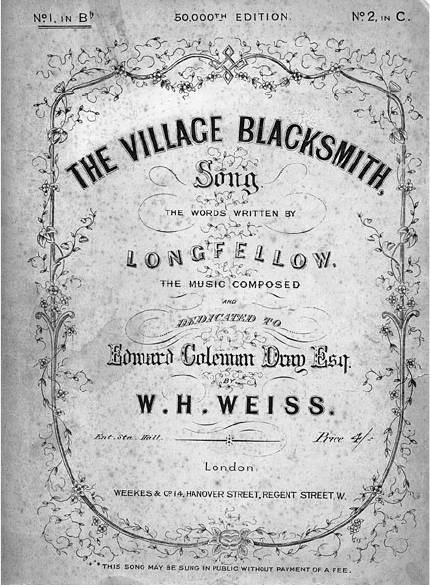

Figure 3.2 The title page of a morally uplifting

drawing room ballad employing tasteful decoration

and different type fonts.

of French entertainment with the risqué, that London reacted more

cautiously to the sauciness of Offenbach’s operettas. On the contrary,

in England they were sometimes lewder. Punch remarked of the pro-

ductions of La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein and La Belle Hélène starring

Hortense Schneider in 1868: “Schneider was far more vulgar in Lon-

don than in Paris, though on her native heath her performance was

witnessed chiefly by ladies of the faster set.”

61

Once again, this opens

up the issue of culture as an area of compromise where no complete

dominance can be achieved. For the musical journalist Henry Chorley,

La Grande-Duchesse, which many found so hilarious and tuneful, repre-

sented “opera in the mire”; he thought it the lowest point to which a

stage work could sink “in offence to delicacy,” and condemned its music

as “trite and colourless.”

62

Much of the cultural change during the century can be seen as

driven by the power and interests of fractions within the middle classes,

but as Kathy Peiss points out, “the lines of cultural transmission travel

in both directions,” and the working class did not passively consume

cultural messages.

63

For example, the African-American musical A Trip

to Coontown, which ran for longer than any other nineteenth-century

show in New York, was described by a Boston reviewer as having

humor that “smacks far more of the street and barroom than of the

drawing room.”

64

And in 1899, the Musical Courier, with reference to

the American ragtime craze, proclaimed: “A wave of vulgar, filthy and

suggestive music has inundated the land.”

65

The irony was that ragtime

idiomatically suited the instrument most imbued with domestic re-

spectability, the piano. However, the flipside was that pianos were also

common in New York’s brothels and honky-tonks.

The presence of different classes in the same venue did not mean

that they mixed. Emile Blémont wrote about cafés-concerts in the

Evênement of February 1891:

There are two publics, different and totally distinct from one another in the

Café Concerts. On the one hand you will find the masses, a trifle heavy, a

trifle slow, but simple-minded, sympathetic and generous. . . faithful to the

old traditional form of song. . . . On the other hand . . . you will find an-

other public which is, in some respects, more highly cultivated. They are

the rakes, the déclassés of literature or trade, forming the bohemia of the

more well-to-do middle class; free lances most of them in their particular

professions of trade or art.

66

Blémont commented that the two publics sat close together but did

not intermingle, and that in some establishments the “popular ele-

ment” dominated, while in others it was the “bohemian element.” The

double clientele was also found in the cabarets of Montmartre (see

chapter 8). In London, the socially mixed music halls were in the cen-

ter and attracted bohemian types from the beginning; the working-

class halls were in the East End and south London. London’s suburbs

Music, Morals, and Social Order 71