Sandau R. Digital Airborne Camera: Introduction and Technology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter 2

Foundations and Definitions

2.1 Introduction

Some preliminary remarks are helpful before the foundations and definitions are

provided in more detail. Optoelectronic imaging sensors are described by param-

eters or functions that characterise the geometric, radiometric and spectral quality

of optical imaging and the quality of the analogue and digital processing of optical

information.

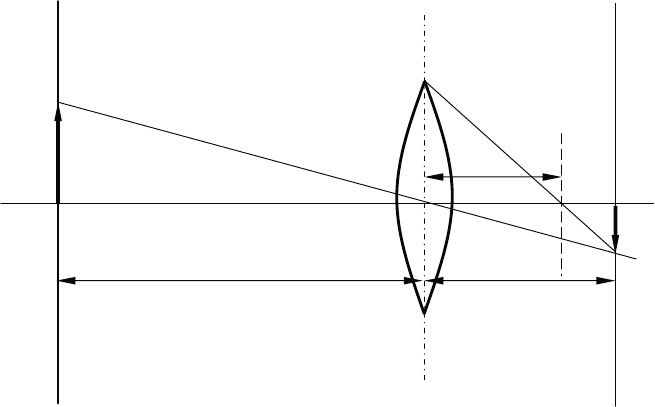

Geometric imaging by the lens of a sensor (which will be considered in more

detail in Section 4.2) is described, as a first approximation, by thin lens (ideal) imag-

ing of an object. If one considers the image of a luminous point P which is located

at distance g in front of the lens then this point is mapped at distance b behind the

lens in a point P’. The relationship between g and b is given by

1

f

=

1

g

+

1

b

, (2.1-1)

where f is the focal length of the lens.

If the point P is located at distance G from the optical axis then the distance B of

point P’ from the optical axis is

B =

b

g

·G (2.1-2)

(see Fig. 2.1-1).

If the image is not observed in the image plane (at distance b from the lens), but

in a shifted plane at distance b ± ε, then the point P is imaged into a circle. The

image becomes blurred, and the blur increases with increasing shift ε. This simple

model of an imaging lens is sufficient for a coarse assessment of the imaging quality,

but is not sufficient for a more precise analysis.

In general, real (multi-lens) optics have imaging errors which violate the ideal

imaging equations (2.1-2) and (2.1-2). These errors are not considered here, but

the reader is referred to McCluney (1994). In high-precision optics the errors are

minimized by elaborate lens corrections. The remaining errors can be measured

31

R. Sandau (ed.), Digital Airborne Camera, DOI 10.1007/978-1-4020-8878-0_2,

C

Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010

32 2 Foundations and Definitions

P'

f

g

b

P

B

G

Fig. 2.1-1 Imaging by a thin lens

in a process of geometric calibration and corrected by software later. If there is a

requirement to measure in images (photogrammetry), the geometric calibration and

subsequent correction must be done very carefully.

Not all effects of optical imaging can be explained by the laws of geometric

optics, because, if we use a better approximation, light is described by waves, which

are characterised by parameters such as wavelength λ, frequency ν, amplitude A,

and phase ϕ. This leads to phenomena of diffraction affecting the imaging quality.

The point P is no longer mapped to a point P’ but to a diffuse spot, the diameter of

which characterises the geometric resolution of imaging. Existing lens errors (aber-

rations) lead to a further deterioration of the image quality. If aberrations are absent,

the imaging lens is said to be diffraction-limited. Because diffraction is a wave

phenomenon, image quality decreases with increasing wavelength λ. The approxi-

mation of geometric optics described at the beginning of this chapter is reached as

λ → 0. Only in this case will a point be mapped into a point.

Light as a waveform also has properties such as coherence and polarisation. In

most cases these phenomena do not play an essential role in the design of a camera

and they are not discussed here. Light is considered as incoherent and unpolarised.

The (partial) coherence of radiation is responsible for the interference of light, which

occurs especially in the use of laser radiation. Whereas for coherent light the wave

amplitudes are superimposed, incoherent light is a superimposition of intensities

(radiances and brightnesses). The amplitudes and phases of incoherent light are ran-

dom functions of space and time (called white noise in the case of fully incoherent

light) and the light must be described by statistical averages of quadratic quantities

(intensities, correlation functions and so on). Real light is neither fully coherent nor

2.1 Introduction 33

totally incoherent – it is partially coherent – but that property will not be used in the

following analysis.

Polarisation follows from the vector character of light. As with any other electro-

magnetic radiation obeying Maxwell’s equations, light is described by electric and

magnetic field vectors which are orthogonal to each other and to the direction of

propagation (transverse fields). If one considers, for example, the electric vector

in a given point of space as a function of time it can describe various curves. If

it oscillates along a straight line the light is linearly polarised. But the vector also

can describe an ellipse (elliptical polarisation) or a circle (circular polarisation) or

even move randomly (unpolarised radiation). Natural radiation, which is often unpo-

larised, can become polarised after reflection or refraction at optical surfaces. This

effect can give useful information on the properties of polarising media, but it can

also lead to radiometric errors if it is not taken into account. If one wants to have

precise radiometry, rather than just attractive pictures, then polarisation should be

studied intensely.

Light is always a superimposition of wave trains with different wavelengths (and

directions of propagation). Therefore, all physical quantities which describe the

radiation, such as amplitudes, phases and intensities, depend on the wavelength λ or

on the wavenumber σ = 1/λ. These functions f(λ) characterise the spectral proper-

ties of light, and f(λ) is the spectrum of the corresponding physical quantity f.Ifthe

function f(λ) is concentrated in a small neighbourhood around a mean wavelength

λ0 then the radiation is (quasi-)monochromatic. Otherwise, the radiation is more or

less broad-band. It can be decomposed into its spectral parts using filters, prisms or

gratings, enabling useful information on light sources or on reflecting, refracting,

absorbing, or scattering media to be obtained. Natural radiation in general is broad-

band, whereas laser radiation can be extremely narrow-band. Connected with the

spectrum is the colour of light, which is not a physical quantity but a phenomenon

of visual perception. Many models have been developed to describe colour more or

less correctly and these should be used if true colour images must be generated.

The physical value which is measured by a radiation detector is proportional to

a time average of the quadratic amplitude of incoming radiation. It is a measure of

the radiation energy in a certain spectral interval reaching the detector during the

integration time and of the brightness too. When that energy must be measured (for

ordinary cameras that is not the case – a good visual impression is enough), then

a radiometric system must be considered. Radiometric systems need very careful

design, because diverse errors can cause considerable deterioration of the quality of

measurement.

The description of light by Maxwell’s equations as a continuous phenomenon in

space and time is only an approximation of its true nature. If one goes to the atomic

range and investigates the emission and absorption of light by atoms and molecules,

it becomes clear that light is emitted and absorbed only as discrete portions of energy

(light quanta or photons). For our purposes it is sufficient to imagine a photon as a

wave train of limited duration and extent with the wavelength λ and the frequency

ν = c/λ, (2.1-3)

34 2 Foundations and Definitions

where c is the velocity of light, and the energy

E = h ×ν, (2.1-4)

where h is Planck’s constant.

Because the emission of a photon is a random event (i.e. the time of emission is a

random variable), natural light is a more or less random superimposition of photons

with a fluctuating photon number in space and time. These fluctuations are called

photon noise, which is the ultimate limit of the radiometric measurement accuracy

of an optoelectronic system.

After the optical system is adequately described, including the radiation source

and the transmitting medium, it is necessary to study the properties of the detector

and the signal processing electronics. Advanced optoelectronic detectors are assem-

bled detector elements arranged regularly on a chip. The continuous radiation field

is sampled by the limited area of a detector element. Owing to the size of the detec-

tor element and the spatial distribution of the sensitivity, the spatial information is

blurred. This blur is superimposed on the blur generated by diffraction of light at

the aperture of the optics. Sometimes the regular arrangement of the detector ele-

ments produces certain unwanted phenomena (aliasing), which can be reduced by a

proper trade-off of optics and detector array. To achieve this, one has to consider the

sampling theorem together with the parameters describing the blur, such as Point

Spread Function (PSF) or Modulation Transfer Function (MTF). Here the Fourier

transform plays an essential role.

In the following sections the characteristics of radiation, optics and sensors,

which have been mentioned only briefly so far, will be discussed in more detail.

The registration of incoherent and unpolarised radiation is of particular interest.

The necessary theoretical foundation is presented together with practical questions,

to which reference is made in later chapters.

Reference may be made to the following books for a deeper insight into the

problems: Goodman (1985), McCluney (1994), Jahn and Reulke (1995) and Holst

(1998a, b).

2.2 Basic Properties of Light

According to the wave theory of light, a light wave propagating in a medium can be

described by the real part of a superimposition of plane waves

A

(

λ

)

·exp

j ·

(

k · r − ω · t

)

. (2.2-1)

Here, k =

2π

λ

·e is the wave vector described by the wavelength λ and the direc-

tion of propagation given by the unit vector e. ω = 2πν is the circular frequency,

which depends on the wavelength according to c = λ·ν (2.1-3). The phase velocity

c is the velocity of light in the transmitting medium. It is connected with the vacuum

velocity of light via c = c

vac

/n (n = n(λ) is the refractive index). The amplitude A,

36 2 Foundations and Definitions

used for coarse estimation. Strictly speaking, it holds only in the interior of a cav-

ity whose walls have the constant temperature T. Such a cavity is filled with the

so-called black body radiation with the radiance

B

λ

(

T

)

=

2hc

2

λ

5

·

1

exp

h·c

λ·k·T

−1

. (2.2-4)

In (2.2-4) h is Planck’s constant, k the Boltzmann constant, and T the absolute

temperature.

For the purpose of calibration, black body radiation is often (especially in the

infrared part of the spectrum) generated approximately by so-called black bodies. In

reality, they always show deviations from Planck’s law (2.2-4), which are described

by the emissivity ε

λ

. A light source which does not receive radiation emits the

radiance

L

λ

= ε

λ

·B

λ

(

T

)

, (2.2-5)

with ε

λ

<1.

An example of a near black body source is the sun. The photosphere of the sun

approximately emits black body radiation with a temperature of about T =5,800 K.

Then the chromosphere absorbs some parts of that spectrum resulting in a radiance

of type (2.2.5).

For the estimation of the radiant energy hitting a detector element, the optical

mapping of a radiating surface by a lens is now considered. Let F

O

be the object

area (which is assumed here to be perpendicular to the principal axis) which is

mapped on to a detector element of area F

D

. Then, according to (2.1-2):

F

D

=

b

2

g

2

·F

O

. (2.2-6)

The radiation emitted by F

O

and reaching F

D

is collected by a lens of aperture D

and area F

L

=

π

4

·D

2

. This radiation is contained in the solid angle (see Fig. 2.2-2)

O

=

F

L

g

2

·cos

(

ϑ

)

=

π

4

·

D

g

2

·cos

3

(

ϑ

)

. (2.2-7)

The detector element, therefore, receives approximately the power

λ

= L

λ

·cos

(

ϑ

)

·F

O

·

O

·λ =

π

4

·

D

g

2

·F

O

·cos

4

(

ϑ

)

·L

λ

·λ.

Using (2.2-6) and considering far away objects (g >> f ; b ≈ f), then one finally

obtains

λ

=

π

4

·

D

f

2

·F

D

·cos

4

(

ϑ

)

·L

λ

·λ =

π

4

·

F

D

f

2

#

·cos

4

(

ϑ

)

·L

λ

·λ. (2.2-8)

38 2 Foundations and Definitions

Formally, the integration is extended over all wavelengths from zero to infinity.

But in reality only a part of that spectrum interacts with the detector element because

of the limitation given by the transmission function τ

λ

.

During a time interval t (integration time) the sensor element receives the

energy

E = · t. (2.2-11)

Because the CCD or CMOS sensors considered here are quantum detectors, it

is sometimes more adequate to consider light as a flux of energy quanta or pho-

tons. These detectors can be characterised by the quantum efficiency η

qu

, which,

on average, generates N

el

electrons from the impinging (mean) number N

ph

of

photons.

To calculate the mean number of photons hitting the detector element, Equations

(2.2-10) and (2.2-11) should be written as

E =

∞

0

e

λ

dλ, (2.2-12)

with

e

λ

=

π

4

·

F

D

f

2

#

·cos

4

(

ϑ

)

·τ

λ

·L

λ

·t +e

λ,scatter

. (2.2-13)

According to quantum theory, the radiation energy at wavelength λ can only be

a multiple of the energy h ·ν = h ·c/λ of a single photon (see (2.1-4) and (2.1-3)).

If n

λ

dλ is the mean number of photons in the interval [λ,λ+dλ], then it follows that

e

λ

= n

λ

·

h · c

λ

and

n

λ

=

λ

h · c

·e

λ

=

π

4

·

F

D

f

2

#

·cos

4

(

ϑ

)

·τ

λ

·

λ

h · c

·L

λ

·t. (2.2-14)

N

ph

=

∞

0

n

λ

dλ is the total number of photons received by the detector element.

Now the mean number of electrons generated inside the detector element can be

calculated if (2.2-14) is multiplied by the quantum efficiency and integrated over the

wavelengths:

N

el

=

π

4

·

F

D

f

2

#

·cos

4

(

ϑ

)

·t ·

∞

0

η

qu

λ

·τ

λ

·

λ

h · c

·L

λ

·dλ. (2.2-15)

2.2 Basic Properties of Light 39

This quantity is converted into a voltage by the read-out electronics. This volt-

age is fed into an analogue-to-digital converter, which generates a digital number

proportional to N

el

. This number can be stored and processed digitally.

The formulae presented above are sufficient for coarse estimation of the detector

signal. For more precise investigations one must consider the space- and time-

dependencies of the radiation quantities. The radiance L

λ

and also the related

quantities depend in general on space and time, which was neglected above. Because

the integration time t of a CCD or CMOS sensor is very short in most cases, L

λ

does not change much during this time and

t+t

t

L

λ

t

dt

may be approximated by

L

λ

(t)t as was done above.

Let X, Y be the coordinates in the object plane (e.g. on the surface of the Earth if

the Earth is observed by a spaceborne or airborne sensor). Then L

λ

is a function of

X and Y. The corresponding coordinates in the image plane (or focal plane) where

the detector is positioned are, according to (2.1-2)

x =−

b

g

·X; y =−

b

g

·Y. (2.2-16)

The quantities which are related to the measured values, therefore, are func-

tions of x and y. They can change considerably from one detector element to

another.

A point (X,Y) on the surface of a radiating object is mapped by the lens (in the

approximation used in geometric optics) on to a point (x,y) in the image plane. The

function L

λ

(X,Y) is then transformed into the function

L

∗

λ

(

x,y

)

= L

λ

−

g

b

·x, −

g

b

·y

, (2.2-17)

which is a function of the coordinates x, y in the image plane.

Therefore, in the formulae presented above, F

D

· L

λ

should be substituted by

F

D

L

∗

λ

x

,y

dx

dy

≈ F

D

· L

∗

λ

(

x,y

)

. This is not true if diffraction is taken into

account. The necessary modifications are considered in detail later when appropriate

mathematics (Fourier transform) is available (Section 2.3).

At the end of this chapter the relationships between radiometry and photometry

will be briefly considered.

If one considers measurement systems then, as above, one has to work with

radiometric quantities. But in the past (and often today too) images have been

evaluated visually. For this purpose certain photometric quantities are used which

are connected with properties (especially the spectral sensitivity) of the human

visual system. To present the relationships between the radiometric and photo-

metric quantities a precise definition of the radiometric quantities already used is

necessary.

The spectral radiance L

λ

is the power of radiation emanating from a surface per

unit wavelength interval (for example, 1 nm), per unit area (for example, 1 m

2

)

40 2 Foundations and Definitions

and per unit solid angle (steradian, sr). It is a function of spatial coordinates x, y,

time t, wavelength λ, zenith angle θ and azimuth angle φ. It has the dimension

[W/(m

2

·sr·nm)]. The radiance L [W/(m

2

·sr)] is given by

L

λ

dλ. The radiance, inte-

grated over the area, is denoted as intensity I [W/sr]. The irradiance E [W/m

2

]ata

radiation receiving surface is

E =

L ·cos θ ·d;

(

d = sin θ ·dθ ·dφ

)

,

which is the power per unit area received by a surface hit by impinging radiation

which is confined to the solid angle . Integration over the area (e.g. of a detector

element) gives the radiant flux [W]. Without integration over the wavelength one

obtains related spectral quantities such as the spectral flux

λ

[W/nm]; =

λ

dλ

.

Let Q

λ

be any spectral radiometric quantity. Then the related photometric

quantity Q

phot

is given by

Q

phot

= 683 ·

Q

λ

·V

(

λ

)

dλ. (2.2-18)

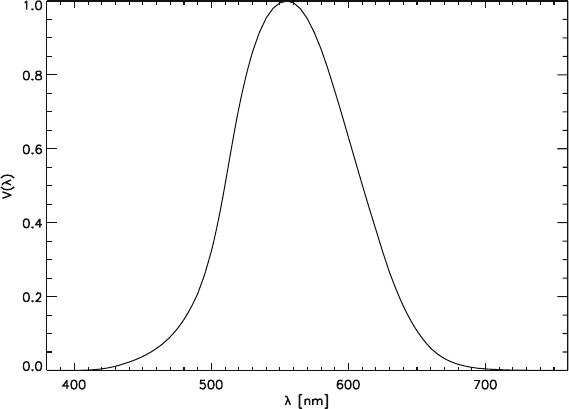

Here, V(λ) is the human sensitivity for photopic vision (i.e. vision by the retinal

cones). It is presented in Fig. 2.2-3. The relationships between the radiometric and

photometric quantities are given in Table 2.2-1.

Fig. 2.2-3 Human sensitivity for photopic vision V(λ)