Sandau R. Digital Airborne Camera: Introduction and Technology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

1.4 Matrix Concept or Line Concept 21

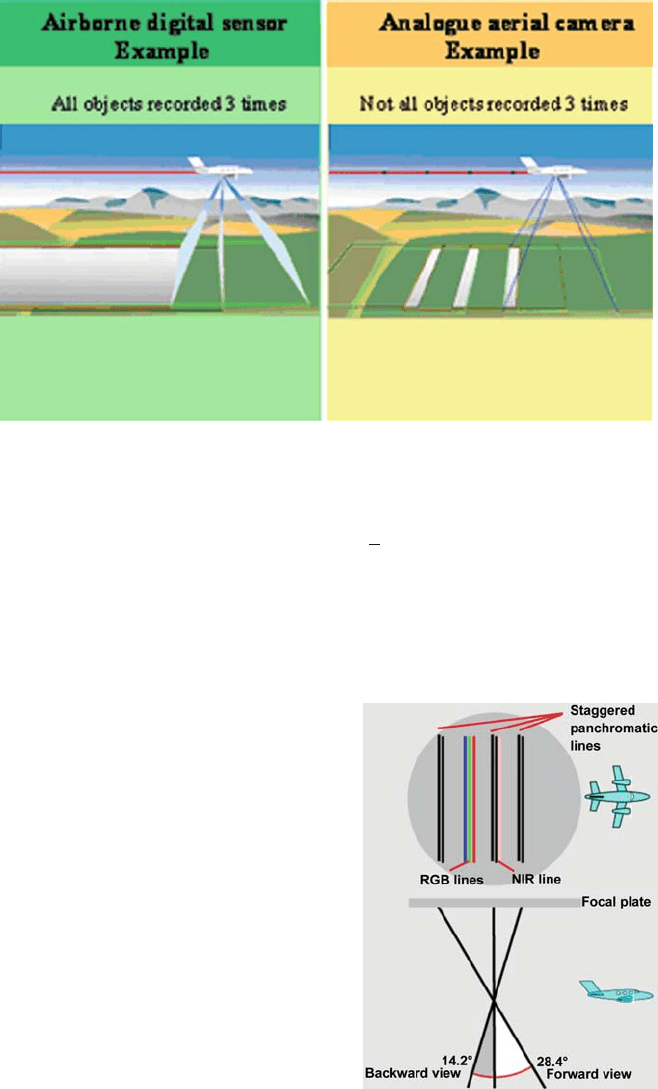

Fig. 1.4-2 Different principles of photography are used in line and matrix cameras for making 3D

measurements (Leica, 2004)

γ

Z

= arctan

d

f

. (1.4-1)

In Fig. 1.4-3, the ADS40 camera, in which the forward and backward view angles

are different owing to the asymmetrical arrangement of the stereo lines, is used as

an example to illustrate the situation. The range of stereo angles – 14.2

◦

, 28.4

◦

and

Fig. 1.4-3 Implementing an

asymmetrical array of stereo

lines (Leica, 2004)

22 1 Introduction

42.6

◦

– of the implementation shown covers the angles listed in Table 1.2-2, which

are required for various applications in photogrammetry and remote sensing.

In the matrix camera, the angle of convergence is a function of the overlap o and

hence variable

γ

m

= arctan

s(1 − o)

f

. (1.4-2)

In (1.4-2), s is the format width of the matrix in the direction of flight and f the

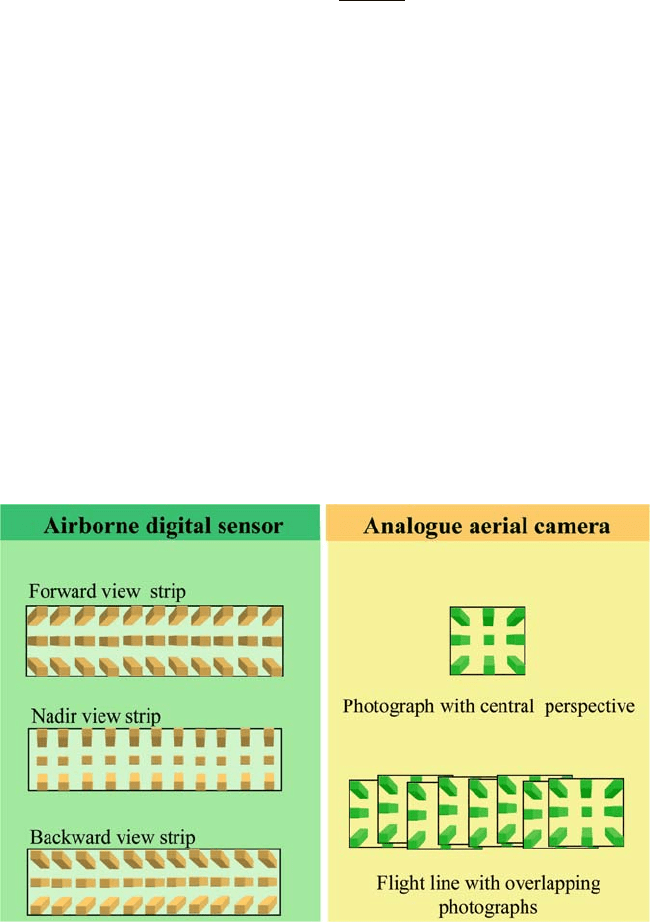

focal length again. To illustrate various perspectives in line and matrix cameras,

schematic representations of tall buildings are shown in Fig. 1.4-4. As with a film

camera, the relief displacement of the central perspective produced with a matrix

camera has two components. The cross-track shift is a function of the distance from

the image centre at right angles to the flight direction and of the height difference.

In the direction of flight, the shift is a function of the distance from the image centre

in the direction of flight and of the height difference.

A special case of central perspective is used in the line camera, namely line per-

spective. The essential difference is that the shift component in the direction of flight

is constant for equal height differences all along the image strip. The line perspective

makes it possible to see images in three dimensions, similar to the way we see nor-

mal stereoscopic pairs, and also to measure the parallax for determining the height.

The uniform perspective for the longitudinal direction of the entire image strip is

advantageous.

Line cameras operating according to the pushbroom principle are designed such

that sufficient energy impinges on the detectors given the smallest permissible GSDs

Fig. 1.4-4 Differences in perspectives of line and matrix cameras (Leica, 2004)

1.4 Matrix Concept or Line Concept 23

and reasonable illumination to satisfy the condition

t

int

≤ t

dwell

(1.4-3)

where t

int

is the integration time and t

dwell

is the dwell time or time of flying over

a GSD. FMC (forward motion compensation) is not required. With matrix cameras,

it is permissible to incorporate TDI mode in the radiometric design when designing

the system. TDI is explained in Section 4.4.2. Suffice it to say here that the energy

reflected by an object on the ground is pushed forward to the pixels of each succes-

sive matrix line. In n shifting and signal accumulation stages, one obtains an n-fold

integration time, increases the signal n-fold and increases the SNR by the factor

√

n.

The reflected radiation is accumulated by the object from n different angles, how-

ever, which influences the precision of height measurements. During this n-fold

integration time, the roll, pitch and yaw also cause image migration, which can be

ameliorated through platform stabilisation. It is expedient to use FMC, therefore,

only if the image migration brought about by changes in the aircraft’s attitude does

not cause greater image migration in the direction of flight than that compensated by

FMC. Nor may cross-track image migration become greater than the pixel dimen-

sion during the integration time. Only then does pixel smearing still remain within

acceptable limits (see also Sections 2.4, 4.1 and 4.10.1).

In most matrix cameras, integration time is controlled by mechanical shutters.

In line cameras, integration time is controlled electronically; moving parts are not

required. Exterior orientation is the same across the whole matrix in matrix cameras.

Individual matrix photographs have to be connected when making image strips,

using pass points at the von Gruber locations. In line cameras, exterior orienta-

tion is the same for all the lines in the focal plane, but it changes with each line

recorded. This is illustrated in Fig. 1.4-5. The consequences for sensor orientation

are described in Section 2.10.

Whereas the requirements which the position and attitude measuring technology

for matrix cameras has to meet correspond to those of analogue airborne cameras,

additional aspects need to be taken into account in the use of multiple-line cameras.

The three-line camera is based on the fact that at least three lines are needed to

establish correct orientation with the aid of pass points at the von Gruber locations

(Hofmann, 1986), but this procedure requires a great deal of computing time. GPS

and IMU systems can support the process of determining the exact orientation of all

lines (see Section 4.9). Cost-effectiveness is a decisive factor when selecting IMU

systems.

Georeferencing following high-precision measurement of external orientation at

each recording position is possible by using measured data on its own, because this

is not a cost-effective solution. Economical measuring systems can be used and

georeferencing results computed within an acceptable time frame in georeferencing

using bundle block adjustment with a relatively small number of linkage points by

incorporating position and attitude values of relatively low precision. In the mean-

time, GPS receivers are also used in analogue airborne cameras and matrix cameras

for navigation purposes and for supporting the generation of image strips. As a rule,

24 1 Introduction

Fig. 1.4-5 Schematic representation of external orientation change for each new line recorded

(Leica, 2004)

differential position determination using kinematic phase measurement is employed

in all camera types. Real-time solutions are nor required.

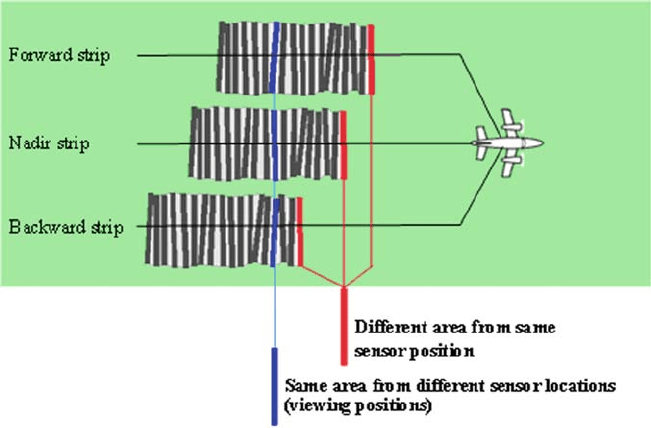

Figure 1.4-6 shows this photo flight situation typical of airborne cameras.

The sensor head of the ADS40 multiple-line camera contains an integrated IMU

selected according to the foregoing criteria. Aspects of the rectification of multiple-

line camera images sketched here are discussed in further detail in Sections 2.10

and 4.9.

Resolution values and performance that should be as close as possible to those

of analogue airborne cameras are among the principal characteristics of digital air-

borne cameras. Resolution and performance are defined by GSD (ground sample

distance, see Section 2.5) and swath width. This applies to both multispectral and

panchromatic channels.

Instead of an airborne camera film, it would be ideal to have a matrix with 80,000

× 80,000 detector elements array in the focal plane. This matrix should have detec-

tors spaced roughly 2–3 μm apart, with spectral responsivities alternating between

blue, green, red and NIR (near infrared). The 20,000 × 20,000 colour detectors

would correspond to analogue aerial photographs in a 23 × 23 cm format that have

been digitized with an 11.5-μm grid. A detector size of 16 × 16 cm to 24 × 24 cm

would be large enough for lenses used in analogue airborne cameras to be com-

bined directly with the matrix. The surface would have to be extremely even with

tolerances in the range of a few micrometres (see Sections 4.2 and 4.5). Such a

matrix cannot be manufactured at an acceptable price today. But there are alter-

natives based on different approaches for the two basic concepts (matrix or line).

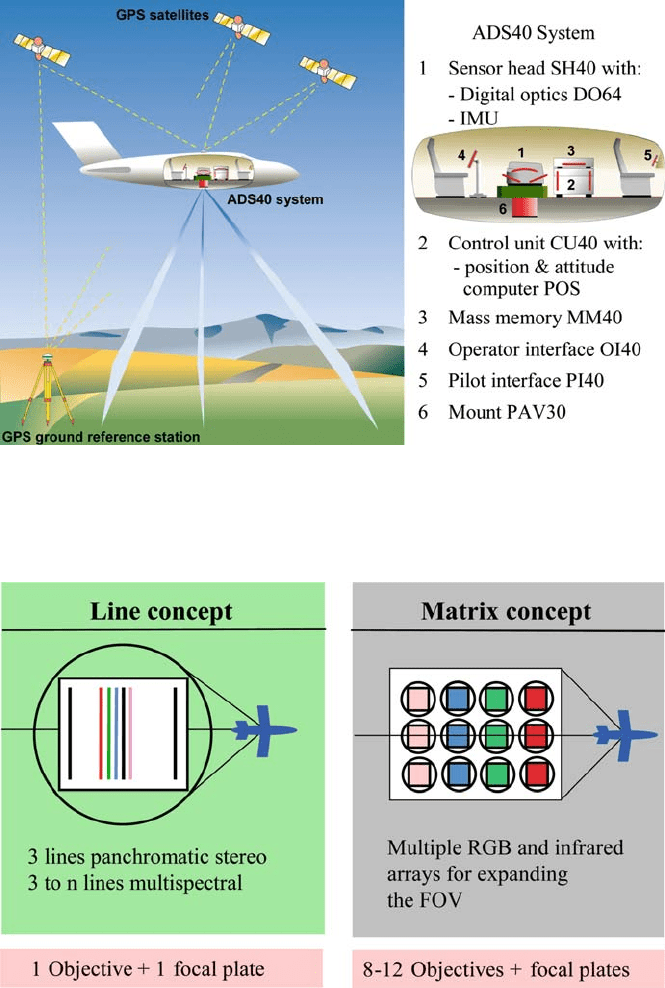

The basic ideas behind the two alternatives are shown in Fig. 1.4-7. In each case,

1.4 Matrix Concept or Line Concept 25

Fig. 1.4-6 Schematic representation illustrating the use of differential GPS in aerial photography

in conjunction with an ADS40 (Leica, 2004)

Fig. 1.4-7 Alternative solutions for digital airborne cameras (Leica, 2004)

26 1 Introduction

a Cartesian coordinate system is constructed, the axes of which represent spectral

resolution along the flight track and geometric resolution across the track in com-

bination with the swath width, thus representing the number of detector elements

schematically.

Since it is easier to construct an array comprising a multitude of faultless detector

elements in a single dimension (line) with good yield than in two dimensions simul-

taneously (matrix), lines are bound to provide higher resolutions at a given stage in

technological development. The current state of the art is lines with 12,000 detec-

tor elements which, in staggered array (see Section 2.5), can accomplish 24,000

scanning operations along the line (see Section 2.5 and Chapter 7).

Matrices with roughly 9,000 × 9,000 detector elements are available today,

although their application in digital airborne cameras is not yet economical.

Currently, matrices with about 7 × 4 k are used (see Section 1.5). Thus, depending

on the required number of sampling points in the swath direction, the appropriate

number of matrix cameras is arranged side by side. As shown in Section 1.5, several

variants are possible.

There are also two basic concepts (matrix or line) with respect to the spectral

co-ordinates shown in the flight direction in Fig. 1.4-7. In the case of the matrix

concept, the appropriate number of cameras must be used to achieve the required

swath width with the specified GSD for each spectral channel or, if several channels

are combined in a camera using special optical processes, then for each channel

combination.

In the case of the line concept, additional lines – corresponding to the number

of required spectral channels – are arranged in the focal plane between the lines

(usually panchromatic) used in topographic mapping. It should be noted that in both

alternative solutions shown in Fig. 1.4-7, the differences in angles of convergence

and exposure time between the spectral channels, on the one hand, and between

spectral channels and the panchromatic channels, on the other, lead to pixel cover

problems during data processing or presentation. These systemic pixel cover prob-

lems arising from angles of convergence and varying recording time points also

occur with analogue airborne cameras, however, when images from several flight

missions using different films (panchromatic, colour, IR) are joined. A major advan-

tage of digital airborne cameras is that all data obtained with analogue airborne

cameras using three different films from three photo flights can be generated on

a single flight. Here, the pixel cover problems result from the overlapping of the

results obtained not on three photo flights but on only one. Also, greater differ-

ences in illumination conditions inevitably occur when images are generated on

three flights in the case of analogue airborne cameras than those generated on a

single flight using digital airborne cameras.

These systemic errors can be avoided only if the angles of convergence between

channels and different time points of imaging can be avoided. This can be done

with camera systems that convey the different spectral light components (R, G, B,

NIR) to different detector systems (matrices or lines) via polychroitic beam-splitting

devices. In large-format digital cameras (see Section 1.5) this can be achieved more

readily by using detector lines and polychroitic beam splitting devices, which cover

1.5 Selection of Commercial Digital Airborne Cameras 27

the airborne camera’s entire FOV, rather than by using matrix-based multi-camera

systems (see Chapter 7).

1.5 Selection of Commercial Digital Airborne Cameras

There are several cameras on the market that are sold and/or used as digital airborne

cameras. A good survey of the different systems from different manufacturers is

given in Petrie and Walker (2007). It gives also a classification of all systems.

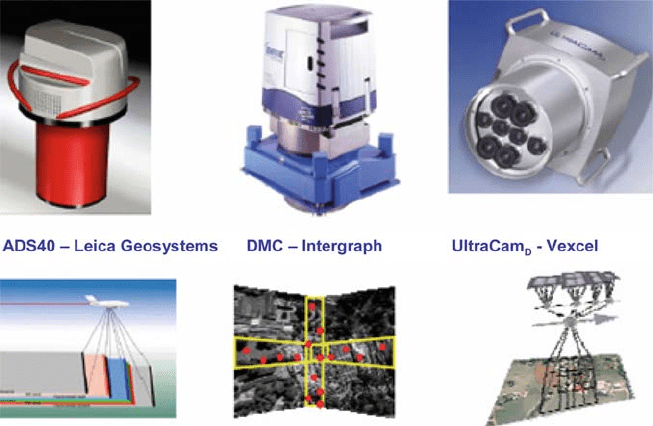

We focus our attention here on the large-format cameras ADS80, DMC and

UltraCam shown in Fig. 1.5-1, which are already being marketed worldwide and

which are also representative of the various approaches.

Fig. 1.5-1 Commercial large-format (Cramer, 2004)

1.5.1 ADS80

The multiple-line scanner ADS40 (Airborne Digital Sensor) made by Leica

Geosystems (Leica, 2004) was developed in cooperation with Institut für

Weltraumsensorik und Planetenerkundung of Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und

Raumfahrt in Berlin. The scanner is based on the three-line concept and is an adap-

tation of the WA0SS stereo camera developed for the Russian Mars 96 mission

(Sandau, 1998), so the ADS40 represents the latest technologies available. It is sup-

plied in various focal plan variants (see Section 7.1). To illustrate the basic principle

28 1 Introduction

of the scanner’s construction, some details of one of its variants are examined here.

The panchromatic CCD line directed vertically downward consists of two lines with

12,000 detector elements each, the elements being spaced 6.5 μm apart and stag-

gered against each other by half a detector width. A synthetic 3.25 μm grid with

24,000 sampling points in the ground track across the direction of flight is produced

through this staggered arrangement. Two similar CCD lines directed forwards and

backwards and, with the 62.7 mm f/4 lens, yield stereo angles of 28.4

◦

and 14.2

◦

respectively. The FOV is 64

◦

in the cross-track direction, so a swath width of 2.4 km

can be achieved a flight altitude of 1,500 m,. At a distance of 14.2

◦

from the cen-

tral CCD line, there are narrow-banded, spectrally separated R, G and B lines with

12,000 detector elements each, suitable for generating true-colour images as well

as for thematic interpretation in remote sensing applications. In addition, 2

◦

from

the central line, there is a line that is sensitive in the near infrared range (NIR). The

filter design and the linear characteristic of the CCD detector elements give the dig-

ital airborne camera the quality of an imaging and measuring instrument. The RGB

channel are perfectly co-registered through special optical means and there are no

chromatic fringes. Table 1.5-1 shows some parameters of the ADS40 in comparison

with the other two digital airborne cameras detailed here. Further details are given

in Chapter 7.

Table 1.5-1 Comparison of parameters of digital airborne cameras (camera head)

ADS40 DMC UltraCam

D

Dynamic range 12 bits 12 bits 12 bits

Frame frequency 800 s

–1

0.5 s

–1

0.77 s

–1

Shutter N/A 1/300–1/50 s 1/500–1/60 s

FMC N/A Electronic (TDI) Electronic (TDI)

Detector type CCD line CCD matrix CCD matrix

Element spacing 6.5 μm12μm9μm

Spectral channels Pan, R, G, B, NIR Pan, R, G, B, NIR Pan, R, G, B, NIR

Panchromatic system

Detector size (y · x) 2 × 12,000 staggered 7 × 4 k 4,008 × 2,672

Number of detectors 3 4 9

Number of lenses 1 4 4

Image format (y · x) 24,000 × strip length 13,824 × 7,680 11,500 × 7,500

Focal length, f# 62.7 mm, f/4 120 mm, f/4 100 mm, f/5.6

FOV (y · x) 64

◦

× N/A 69.3

◦

× 42

◦

55

◦

× 37

◦

Multispectral system

Detector size (y · x) 12,000 3,072 × 2,048 4,008 × 2,672

Number of detectors 4 4 4

Number of lenses 1 4 4

Image format (y · x) 12,000 × strip length 3,072 × 2,048 3,680 × 2,400

Focal length, Focal

length f#

62.7 mm, f/4 25 mm, f/4 28 mm, f/4

FOV (y · x) 64

◦

× N/A 69.3

◦

× 42

◦

61

◦

× 42

◦

N/A – not applicable

1.5 Selection of Commercial Digital Airborne Cameras 29

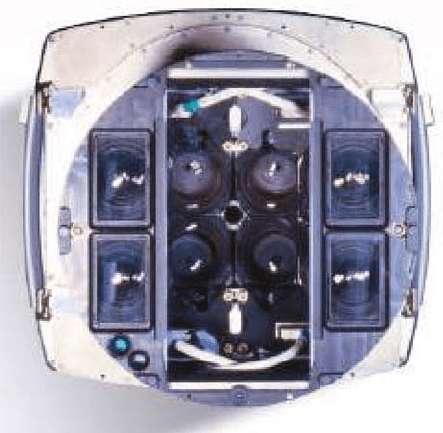

1.5.2 DMC

The matrix-based camera system DMC (Digital Mapping Camera) from Intergraph

(Intergraph, 2008) uses four 7 × 4 k matrices behind four lenses whose optical

axes are slightly inclined in order to produce a panchromatic image of 13,824 ×

7680 pixels in central perspective from the butterfly-shaped component images (see

Section 7.2). The system’s FOV is 69

◦

× 42

◦

, its pixel size is 12 μm and its focal

length 120 mm. The maximum repetition rate of two frames per second makes for

large image scales and small GSDs. In addition to the four panchromatic cameras,

there are four multispectral cameras for R, G, B and NIR with matrix sizes of 3 ×

2 k. The focal lengths of 25 mm ensure that the multispectral coverage of each

exposure is the same as that of the image array from the four panchromatic cameras.

Pan-sharpening is used to produce colour images. Figure 1.5-2 shows the DMC’s

lens array: the inner four lenses generate the panchromatic image, whereas the outer

four lenses, the four colour separations. Some of the parameters of the DMC are

shown in Table 1.5-1 in comparison with the two other digital airborne cameras

covered here.

Fig. 1.5-2 The DMC as seen from below. The four inner cameras generate the panchromatic image

(Z/I Imaging, 2003)

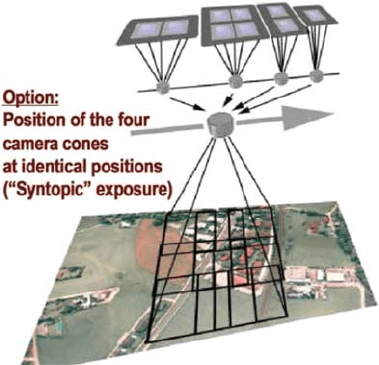

1.5.3 UltraCam

The Vexcel UltraCam approach (see Section 7.3) uses nine CCD matrices with 4,008

× 2,672 detector elements to generate a panchromatic image of 11,500 × 7,500

30 1 Introduction

Fig. 1.5-3 The panchromatic

image is made from nine

component images (see

Gruber and Manshold, 2008)

pixels (see Gruber and Manshold, 2008). Figure 1.5-3 shows how the patchwork-

like montage of the composite image is produced.

The four colour images are generated with four additional cameras with focal

lengths of 28 mm. The associated larger outer lenses can be seen in Fig. 1.5-1.

Colour images of higher resolution are generated with the aid of pan-sharpening.

Some of the parameters of the UltraCam

D

are shown in Table 1.5-1 in comparison

with the two other digital airborne cameras covered here.