Roll Forming Handbook / Edited by George T. Halmos

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

As forming continues away from center,closer to the edges, several center rolls can be deleted

with the exception of the top and bottom guide rolls for one cell at each or at everysecond pass.

Complete sets of top and bottom rolls, which fully envelop the section, are only supplied for the

last twopasses. The above described principle can eliminate 25 to 45% of the rolls by replacing

them withlowerpriced spacers.

5.12.10 Scoring (Grooving)Rolls

The recommended design for scoringrolls is mentioned in Section 5.6.2 (Splitting) and Section 5.12.5

(Application of Radii).

5.12.11 Cutouts for Embossments and Other Protrusions

Embossments or groovesare frequently formed in the first passes. To ensurethat these protrusions from

flat surfaceare not “squashed back,”the rolls in the subsequent passes havetobecut away.Itissuggested

that the cutouts should be longer than the shape of the protrusion. If the cutout has the same size as the

protrusion, aslight deviation in shoulder alignment or setup will reform the longitudinal grooves or

squash the embossments. Because the protrusions are already formed, it is better to use oversized cutouts,

not touching the protrusions (Figure5.159).

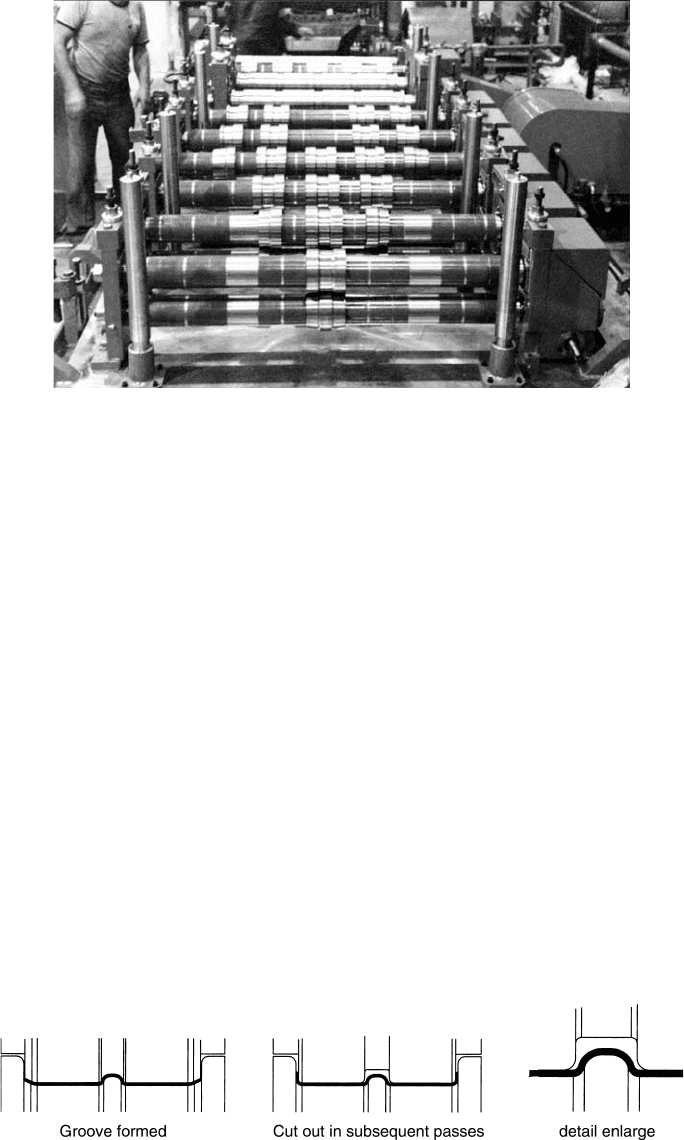

FIGURE 5.158 In panel mills, most passes do not requirefull set of rolls.

FIGURE 5.159 Passes following the forming of grooves require generous cutouts to prevent the reforming or

damaging the grooves.

Roll Forming Handbook5 -92

5.12.12 Overbending

Metals roll formed at room temperature will display“springback”(Figure 5.160). To obtain the angle

specified on the drawing (

a

), the section must be overbent by moreorless the same degreeasthe

springback. The amount of springback is influencedbymanyfactors (see also Section 5.4.3). The

springback and thus the angle of overbending will increase if:

*

The yield strength and the tensile strength of the material is higher

*

The elastic modulus ( E )islower

*

The r : t ratio is larger

*

The gap between the male and female rollsisraised

*

The bending angle is belowcertain limit (small angle bending)

Because the springback can varyfrom coil to coil and even within acoil, the degreeofoverbending by the

rollsshould be adjustable.

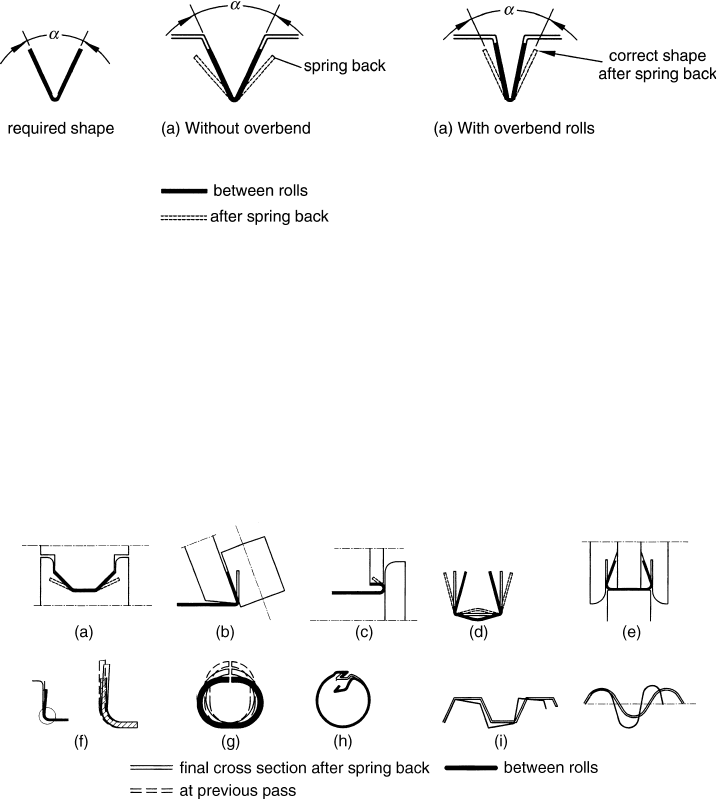

Some of the frequently used overbending methods and rolls are shown in Figure5.161a–i.

*

Figure5.161aisasimple method of overbending used when arelatively small springback angle is

predictable. Springback adjustabilityisminimal.

*

Figure5.161bisatypical arrangement for overbending with side-rolls. This method can be

applied to awide varietyoffinished angles but the maximum angle is limited by the possible

chipping or breaking of the too-thin male roll.

FIGURE 5.160 Overbending is required to counteract springback and to achieve the required bending angle.

FIGURE 5.161 Different overbending methods can be used.

Roll Design 5 -93

*

Forhems (fold-back), the degree of overbending can be adjusted by lifting or lowering the top

rolls (see Figure5.161c). This method can be applied from an angle of approximately 1208

(depending on leg length) to bending over 1808 (teardrop shape).

*

Figure5.161dshows howoverbending can compensate for springback by utilizing afalse bend.

This is arelatively flexible method and is applicable to anyangle including partially closed

sections.

*

Figure5.161e, one of the oldest (and still frequently used) methods, is overbending angles with

tapered rolls. Adjusting the rolls up and down will change the degree of overbend, but

considerable up and down movement is required when the springback variation is large. It is

morefrequently used to overbend predictable small springback. This method is applicable to

bends between 90 and 1808 .

*

Figure5.161f—after forming a90 8 angle, asmall “constant radius”bend adjacent to the 908

bend can provide an overbend. Asmall up and down movement of the upper roll can change

the overbend angle. It is assumed that after springback, the product will havethe correct angle

and the right width. Accordingtoanexperienced rollformer [414], this method helps to reduce

flaretoo.

*

Springback in nonwelded tubes willcreate alarger than the desired slot. The slot can be closed

by forming avertical oval at aprevious pass followed by an overbend roll producing aslightly

oval section in the horizontal direction (Figure5.161g). After springback, the section willbe

circular with asmall or no gap between the edges.

*

Figure5.161h—one edge of atubular section to be lock-seamed can be overbent towards the

tube center to achieve the required overlap for lock-seaming.After springback, the lock-seam

process can be completed.

*

Figure5.161i—the outside corrugations, close to the edge of roll formed panels made from

highstrength material, will haveconsiderable springback. The result is shallower edge

corrugations and wider panel than required. To compensate for springback, some of the outside

bend lines can be overbent by afew degrees (depending on the material). The springback of

these overbent angles will yield the correct cross-section.

5.13 Calculating Roll Dimensions Manually

The flower diagram shows the cross-section of the partially formed strip at each pass. To startthe roll

design, the designer has to calculate the geometryofboth the top and bottom surfacesofthe strip and

establish top and bottom roll pass diameters at each of the passes.

The rollgeometrycalculations are similar to the calculation used to establish strip width. The main

difference is that the rollgeometryhas to be established for both top and bottom roll surfaces at each pass

including side-roll passes.

Everyroll designer has aslightly different approach to the calculations, which are sometimes

augmented or shortcut by making drawings in large, usually a10:1 scale.

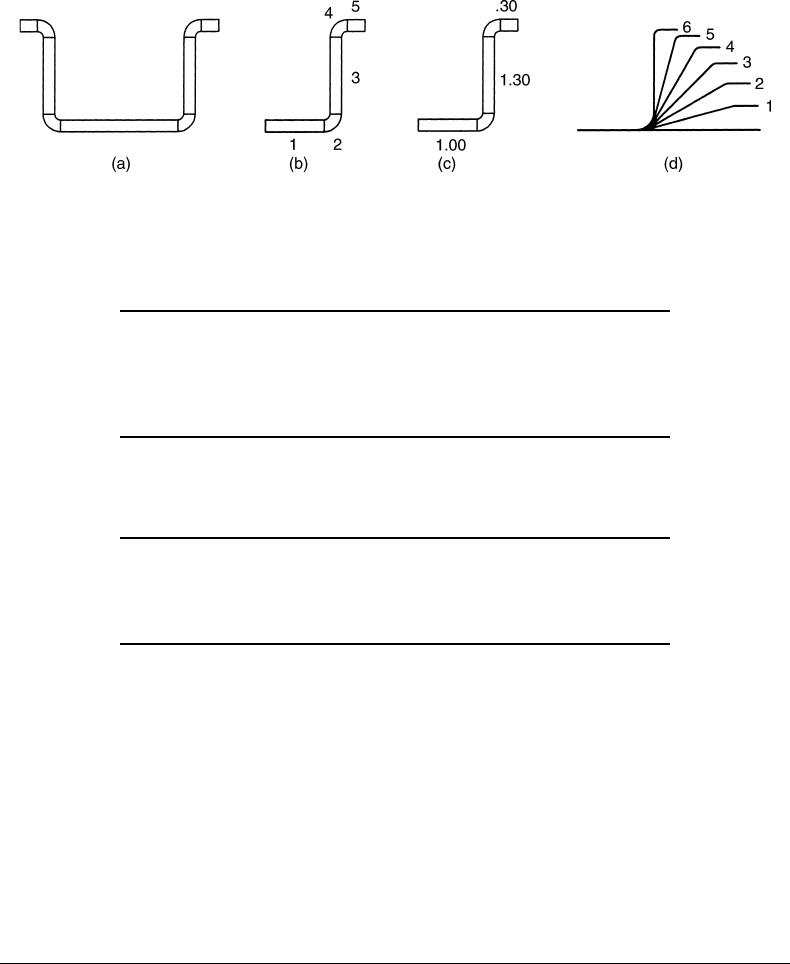

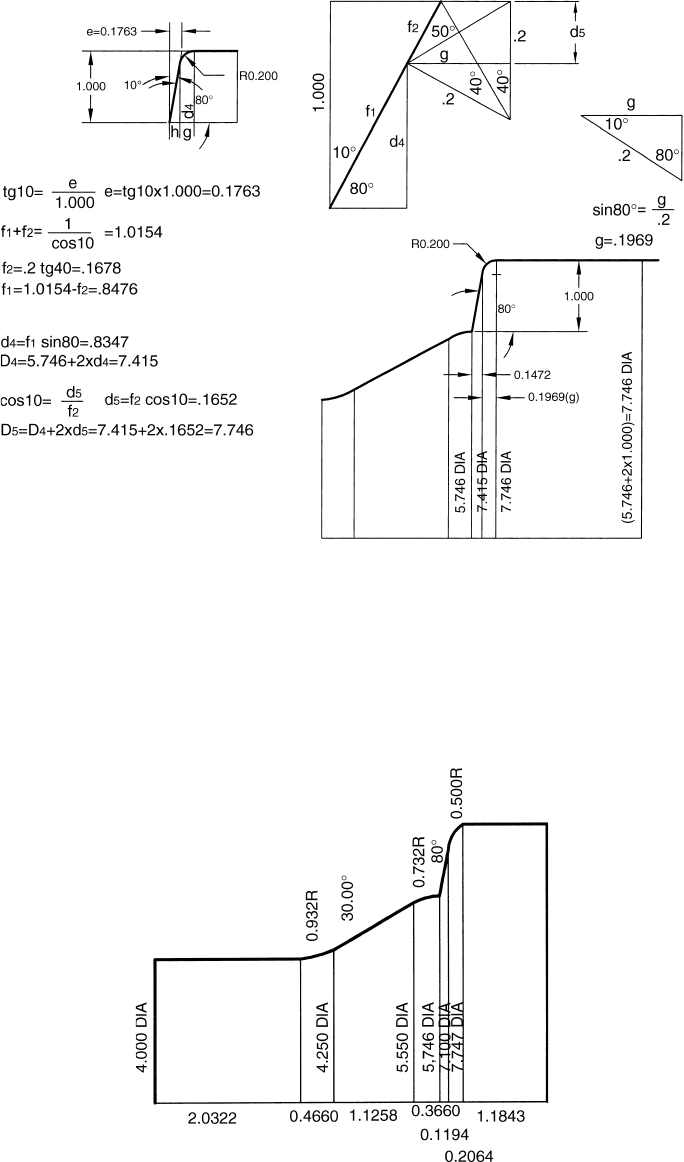

The following example shows one method of calculation of a“hat” section shown in Figure5.162.In

Figure5.162a, the drawing shows the finished hat section, Figure5.162bshows half of the cross-section

with straight and curvedelement numbers starting at the centerline (vertical guide plane). Figure

5.162cshows the length of the straight elements. The inside radius and thickness are assumed to be

0.200 in. Figure5.162dshows the flower diagram using 6passes. Note that this example is designed for

demonstration purposes only and does not reflect the optimum forming angles.

(a) Blank Size (StripWidth) Calculation:

Element #2 (and #4) use Equation 5.7

L ¼ 0 : 0174533 £ 90ð 0 : 2 þ 0 : 33 £ 0 : 2 Þ

L ¼ 1 : 570797 £ 0 : 266 ¼ 0 : 4178

Roll Forming Handbook5 -94

(b) Calculating Bending Radius for Constant ArcBending (use Equation 5.15)

For simplicity,only Pass #2,Pass #4,and Pass #6are calculated.

ForPass #2,

a

¼ 308 R

2

¼ð180=

p

Þð: 4178= 30Þ 2 ð 0 : 33 £ 0 : 20Þ¼: 732

ForPass #4,

a

¼ 608 R

4

¼ð180=

p

Þð: 4178= 60Þ 2 ð 0 : 33 £ 0 : 20Þ¼: 333

ForPass #6,

a

¼ 908 (final section) R

6

¼ .200

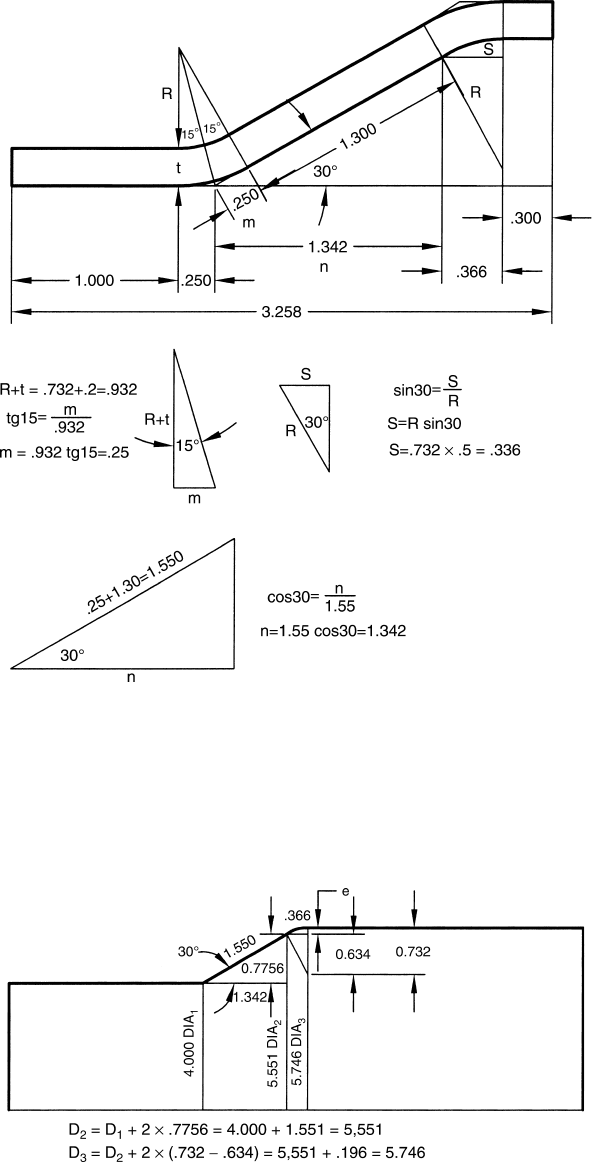

(c) Calculating Roll Surface Geometry of Bottom Roll in Pass #2.

Fordetails, see Figure5.163 to Figure5.165.Figure5.166 shows the final dimensioned roll

drawing for the right half of the second pass bottom roll.

5.14 Computer-Aided Roll Design

One set of rolls maycontain several hundreds or thousands of dimensions. The dimensions are inter-

related within aroll, between the top and bottom rolls in apass, and with all the other passes.

As technologyimproved, the trigonometrical calculations by using log tables havebeen advanced to

mechanical and eventually to electronic calculators. The latest step in the development was to change to

computers.

In addition to the speed, computer-aided roll design eliminates the tedious, monotonous calculations,

drawings, recalculations, and redrawings. Each program and drawing can be savedand retrieved. Roll

drawings can be replotted or modified at anytime. The new software packages incorporate many

convenient time-saving utilityprograms such as cost estimates, roll weight calculations, tool blank cutting

lists, and so on.

Element #1 1.0000 (straight)

20.4178

31.3000 (straight)

40.4178

50.300 (straight)

FIGURE 5.162 Finished section is broken down to straightand curved elements.

t ¼ .20 6passes

a

1

(158 )15 8

k ¼ .33

a

2

(158 )30 8

R ¼ .20

a

3

(158 )45 8

a

4

(158 )60 8

a

5

(158 )75 8

a

6

(158 )90 8

Roll Design 5 -95

The computer-aided roll design software packages varyindegreeofsophistication, speed, and

capabilityofproviding all the design featuresused in the manual roll design. The improved software has

opened the door to change roll design from arttoscience.

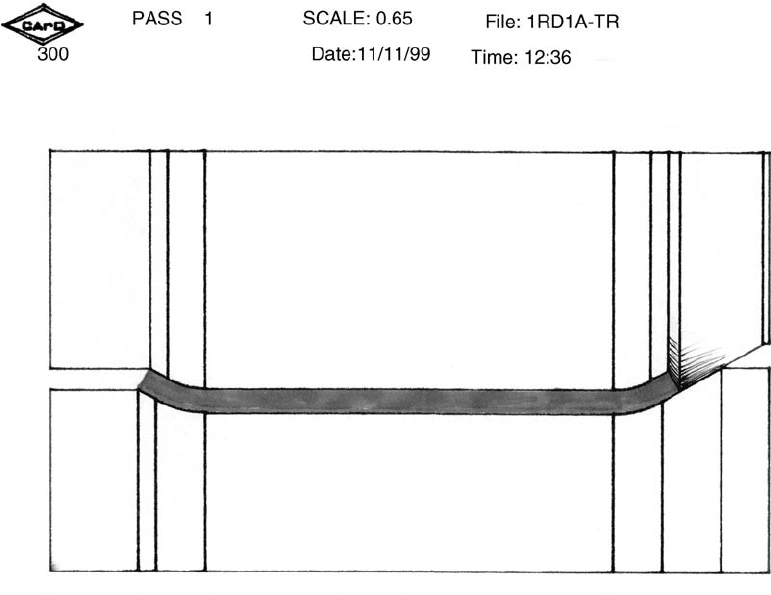

In most computer-aided roll design systems, the design startswiththe input of the mill and other

pertinent data (maximum material thickness, “ k ”factors, etc.). The next step is to generate the finished

FIGURE 5.163 Manual calculation of cross-section.

FIGURE 5.164 Calculating the first elements of aroll.

Roll Forming Handbook5 -96

cross-section by entering the length of straight elements and the inside radius, angle, direction of bending

of the curvedelements, and the “ k ”factor.The blank size (strip width) is then automatically calculated.

Forrolldesign, the “plus” width toleranceshould be added to the calculated strip width. After the flower

is completed, the preliminary(raw) roll design commences by enveloping the section with the top and

FIGURE 5.165 Calculating additional elements of the roll.

FIGURE 5.166 Fully dimensioned rolls.

Roll Design 5 -97

bottom rolls at each pass, with lines commencing from the center line of the top and bottom shafts as

shown in the left side of Figure5.167.

This task is completed in seconds. The designer has to refinethe rawrolls, taking into consideration

several other factors such as howthe leading edge of the strip will enter into the gap between the rolls,

whether it is necessarytotrap the edges to improvetolerances, howthe rolls will be split, wheretomake

cutouts, how to add radii to the roll edges, where to apply side-rolls, spacers, and so on. All of these

decisions are based on the experience of the designer and are influenced by the factors described in the

previous sections of this chapter.

Some programs provide only “raw”roll drawings and other features enveloping the product at each

pass, working from shaft centers. To complete the roll designs, the output of these systems is further

refined by one of the commercially available CAD systems. These relatively inexpensive computer-aided

roll design software are used most frequently by the roll designers.

Other,moresophisticated systems completethe roll designs by adding all the featuresnormally

applied by manual design. They can trap,add lead-in flanges, radii, split spacers, and create setup

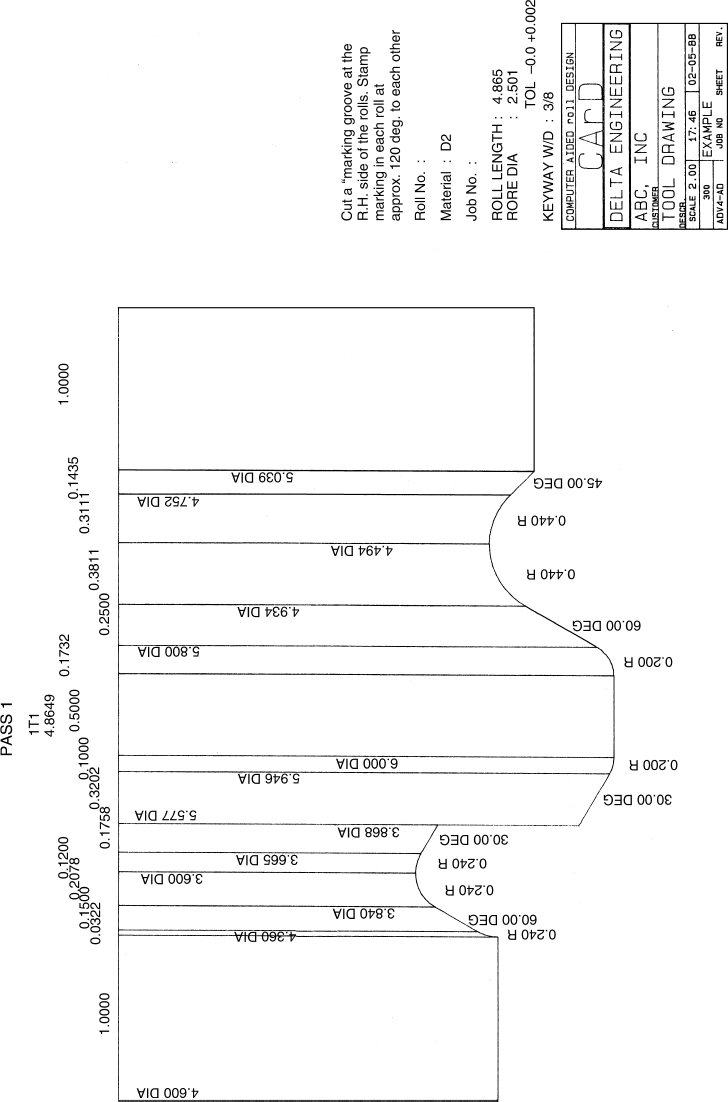

drawings (Figure5.168 and Figure 5.180). Other available software can calculate the bending allowance,

recommend the required number of passes to form the section, prepare quotations, roll cutting lists

and CNC programs for machining,and they may haveadditional features. Another software package

calculates and graphically shows the anticipated stresses generated by the forming at each pass

(Figure5.169). All these computer-aided roll design systems, at different levels, havefound widespread

applications to savethe designer’stime and provide better and moreaccurate rolldrawings.

Further programs havebeen developed by researchers either developing their own programs or using

the commercially available finite element modeling packages [73]. Manyofthe researchers conducted

experiments withsimple sections and, under given conditions, they are able to simulate surprisingly

FIGURE 5.167 “Unedited” (raw) rolls, top and bottom rolls envelop the sections (left-hand side). Lead-in flange

added on the right-hand side.

Roll Forming Handbook5 -98

FIGURE 5.168

Some software can add trap

,lead-in flanges, radius, and other features to

complete the

roll.

Roll Design 5 -99

accurately asimple roll forming process. Most of these simulations require large computers and lengthy

CPU time, which are not available to most roll designers, but some of the results havefound their way

into commercially available roll design systems.

However,regardless of the sophistication of the presently available programs, the know-how and

expertise of the rolldesigners cannot be replaced. There is no doubt that further research in this field can

yield additional data that willreduce the uncertainties which still exist in the roll design.

The following examples will show how asimple factor,such as the sequence of bending established by

the designer,willinfluence the flowofmaterial, the stresses developed in the strip and the provision for

the operator to compensate for the nonuniformityofthe material.

5.15 Examples

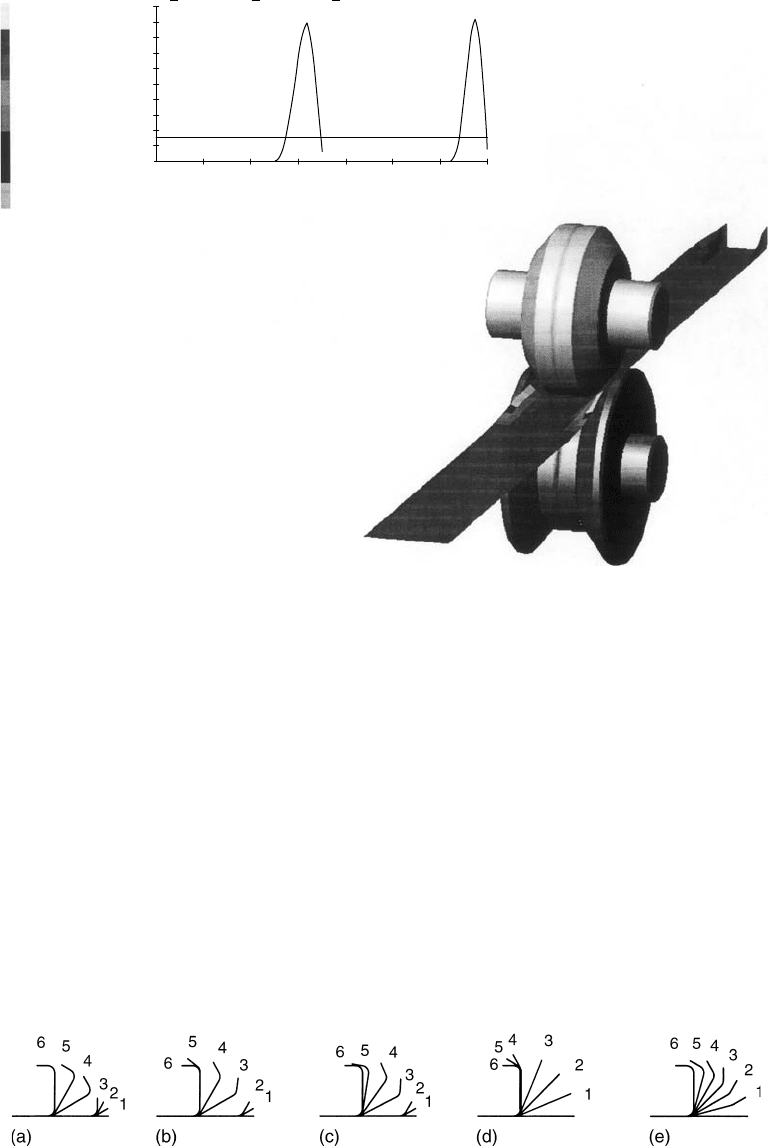

The first example shows some but not all of the bending sequence possibilities for asimple “C” channel

illustrated in Figure 5.170.

Figure5.170aLips at edges are formed completely in the first passes,

Figure5.170bLip forming starts at the first pass, but it is completed in the sixth (last) pass,

Figure5.170cSame as Figure5.170b, but the final lip bending is in Pass #5,

Figure5.170dLegs are formed first, lips are formed in the last pass.

Figure5.170eAll angles are bent in each pass.

In the case of more complicated shapes, the permutations in forming sequence and magnitude are

limitless.

Even the forming of asimple “U” channel can be accomplished in different ways depending on the

number of passes and the preferenceofthe designer (Figure5.171).

*

Shortlegs formed from thin material may be accomplished in 2passes (Figure5.171a). Forthick

or highstrength material, the first pass may requireavery shallow bend to drive the material in.

This is equally applicable to Figure5.171b–e. Examples shown in these figures disregard the

overbending requirements.

*

Figure5.171bshows the same section, but because of the condition, the leg is formed in 3passes.

Some designers may elect to haveaneven increase in all the process (b1) or haveasmaller increase

in the first and third passes, and alarger one in the second pass.

*

If longer length or other conditions necessitate morepasses, then again the designer may elect to

have4equal increase in angles (22.58 per pass; see Figure5.171c1) or 208 in the first and last pass,

and 258 in the second and third passes (Figure5.171c2), or even smaller first and last pass

deformation (15 and 308 in the second and third passes).

*

Some designers divide the horizontal axis to equal distances to establish the bending angles

(Figure 5.171d). This figure shows the forming in five passes. The author does not recommend this

approach.

*

Awell-proven approach is to add asmall first pass forming angle, about 158 ,depending on the

thickness and mechanical properties of the material, to ensure asmooth, unaided entryofthe strip

end into the first pass. Forthicker,highstrength material, this angle may havetobereduced to 0 8 .

*

The last pass may be only a58 bend from 85 to 908 (Figure 5.171e). The remaining angles (in the

example shown on this figure) 708 is divided by 4(because thereisatotal of six passes in the

example). The second and the one before the last bending will be reduced and the in-between

angle increased to arrive to the total 908 (e.g., 10, 17, 20.5, 20.5, 17, and 5 8 ). This approach

provides the closest to asmooth slow-startslow-finish and faster in-between bending. The angles

maybecorrected by viewing the top view of the flow diagram to provide asmooth “S” shape.

There is an unusual, but veryeconomical, way to form deeper channels from thin material. To minimize

edge strain, the full depth is achieved in along horizontal center distancebetween an entrypass and

Roll Forming Handbook5 -100

the first pass. The entrypass (Figure5.172)has averyshallowcurvaturetohelp to form the material

(EP). At asufficient distance, in the first pass of the mill, the section has afull depth “U” shape (1). The

radius of the “U” should be large enoughnot to create permanent deformation in the material

(approximately 40 to 60 times material thickness for mild steel). In the second pass (2), the bottom of

the section is flattened with aradius in the opposite direction to compensate for springback. Asizeable

section of the legs will also be straightened to the bend line, applying ashallowcurvatureopposite to

the previous bending.The third pass (3) finalizes the section. Guiding the edges into the first pass is

important to keep the length of the legs uniform.

The forming of ribbed panels depends upon whether the number of ribs is even or uneven.

Figure5.173ashows four ribs symmetrical to the center line. In this case, the center of the panel remains

Center %

1.6946

1.3557

1.0168

0.6778

0.3389

0.0000

− 0.1915

− 0.3831

2.0

1.6

1.2

0.8

0.4

0.0

200.0 400.0

600.0 800.0

1000.0 1200.0 1400

1, side 2, side

strain Limit

Longitudinal distance [mm]

CourCenter Strain

%

FIGURE 5.169 Forming stresses can be calculated and graphically represented by some software. (Courtesy of data

MSoftware GmbH.)

FIGURE 5.170 Different ways to form “C” channels.

Roll Design 5 -101