Pumping Station Desing - Second Edition by Robert L. Sanks, George Tchobahoglous, Garr M. Jones

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the

annual cost.

By

following their method

of

calcula-

tion,

the

designer

can

then accurately evaluate power

costs

for

alternatives.

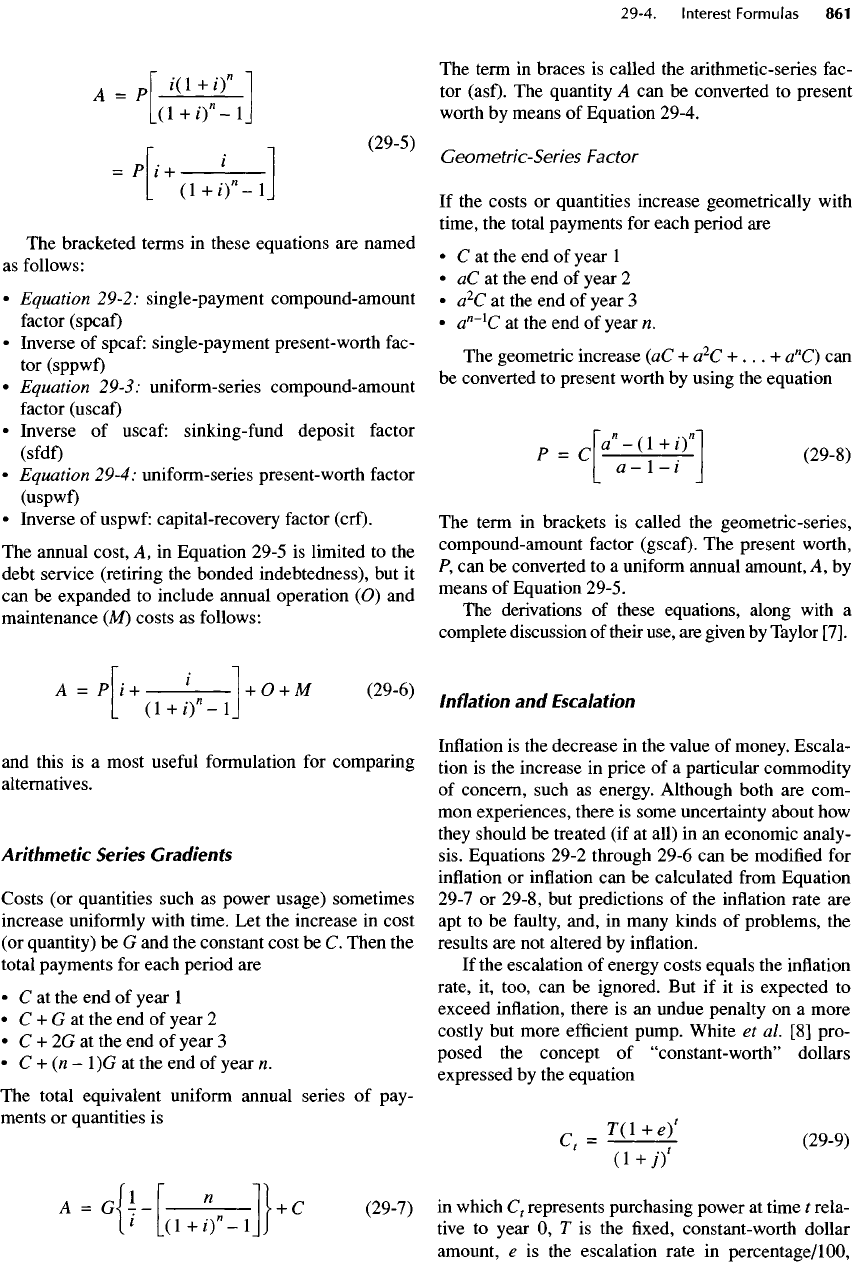

29-4. Interest Formulas

The

comparative worth

of two or

more alternative

plans

can be

evaluated

on the

basis

of

either annual

cost

or

present worth.

Equivalence

Costs

can be

compared only

on

some equivalent basis

such

as

present worth

or a

uniform

series

of

annual

payments.

The two

basic formulas

for the

relationship

between present worth,

future

sum,

and

periodic pay-

ments

are

F =

Pf(I+/)"]

(29-2)

F =

Ap

1+

?"-

1

!

(29-3)

where

/

is the

interest rate

(in

decimals

or

percentage/

100)

per

payment period,

n is the

number

of

payment

periods,

P is a

present (lump)

sum of

money,

F is the

future

(lump)

sum of

money

at the end of n

periods

equivalent

to P at

interest

rate

/,

and A is the

uniform

end-of-period (usually annual) payment equivalent

to

a

present (lump) sum.

If the

payment period

is, for

example, monthly,

the

annual interest rate

is

divided

by

12 and n is

multiplied

by 12.

Other formulas

can be

derived algebraically

from

Equations

29-2

and

29-3

as

follows:

P=

F

d

+

O"

r

»

I

(

29

'

4

>

=

4

(1+0

1

I

L

/(1

+

O" J

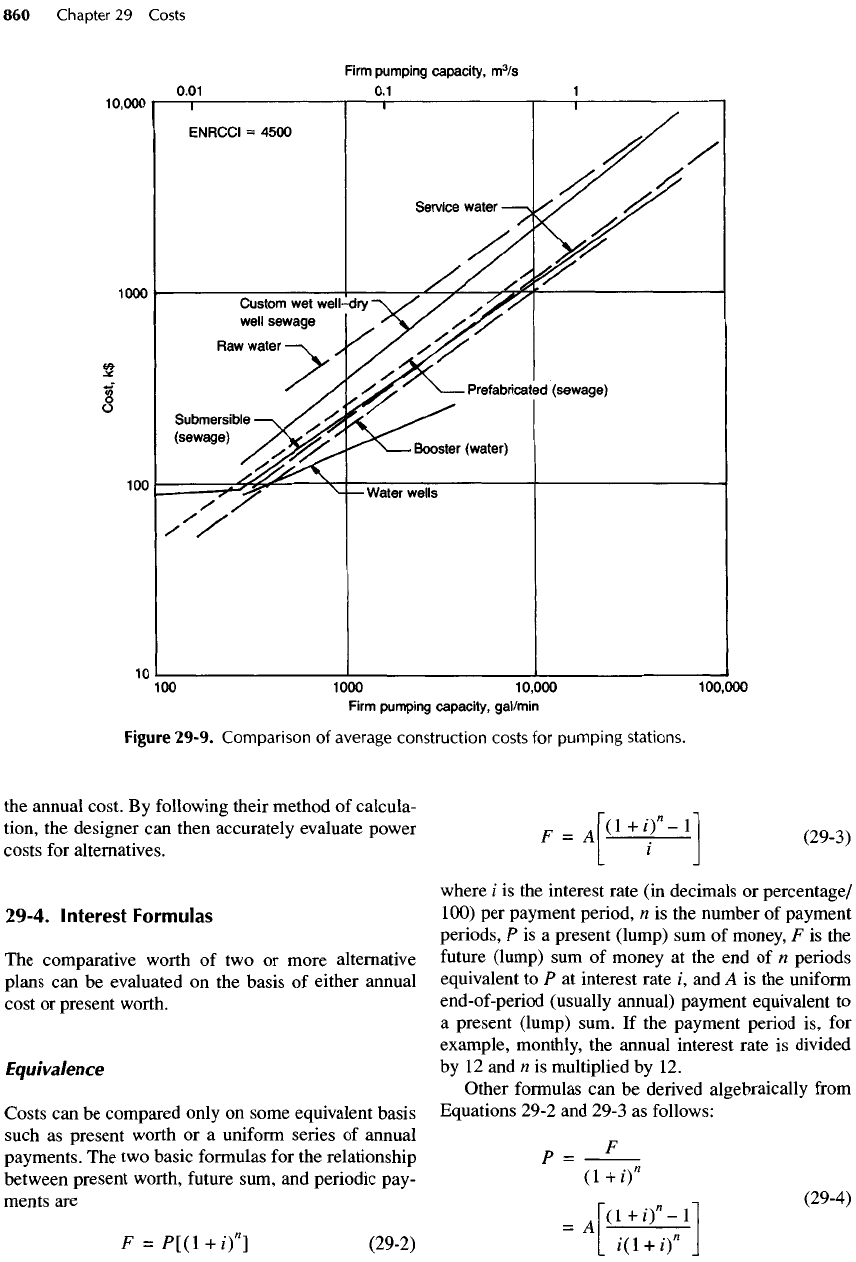

Figure 29-9.

Comparison

of

average

construction

costs

for

pumping

stations.

A

=

4'

(1+/)

"

1

Ld+o"-iJ

r

.

i

(

29

-

5

)

=

/>/

+

'

L

(i+o"-ij

The

bracketed terms

in

these equations

are

named

as

follows:

•

Equation

29-2:

single

-payment

compound-amount

factor

(spcaf)

•

Inverse

of

spcaf: single-payment

present-

worth

fac-

tor

(sppwf)

•

Equation

29-3:

uniform-series compound-amount

factor

(uscaf)

•

Inverse

of

uscaf:

sinking-fund

deposit

factor

(sfdf)

•

Equation 29-4:

uniform-

series

present-

worth

factor

(uspwf)

•

Inverse

of

uspwf: capital-recovery

factor

(erf).

The

annual cost,

A, in

Equation 29-5

is

limited

to the

debt service (retiring

the

bonded indebtedness),

but it

can be

expanded

to

include annual operation

(O) and

maintenance

(M)

costs

as

follows:

A-Pi+

l

+ 0 + M

(29-6)

.

(1

+

iT-lJ

and

this

is a

most

useful

formulation

for

comparing

alternatives.

Arithmetic

Series

Gradients

Costs

(or

quantities such

as

power usage) sometimes

increase

uniformly

with time.

Let the

increase

in

cost

(or

quantity)

be G and the

constant cost

be C.

Then

the

total payments

for

each period

are

• C at the end of

year

1

• C + G at the end of

year

2

• C + 2G at the end of

year

3

• C +

(n

-

I)G

at the end of

year

n.

The

total equivalent

uniform

annual series

of

pay-

ments

or

quantities

is

A

= G\

l

n

1

+ C

(29-7)

I*

Ld

+

'T-iJI

The

term

in

braces

is

called

the

arithmetic-series fac-

tor

(asf).

The

quantity

A can be

converted

to

present

worth

by

means

of

Equation 29-4.

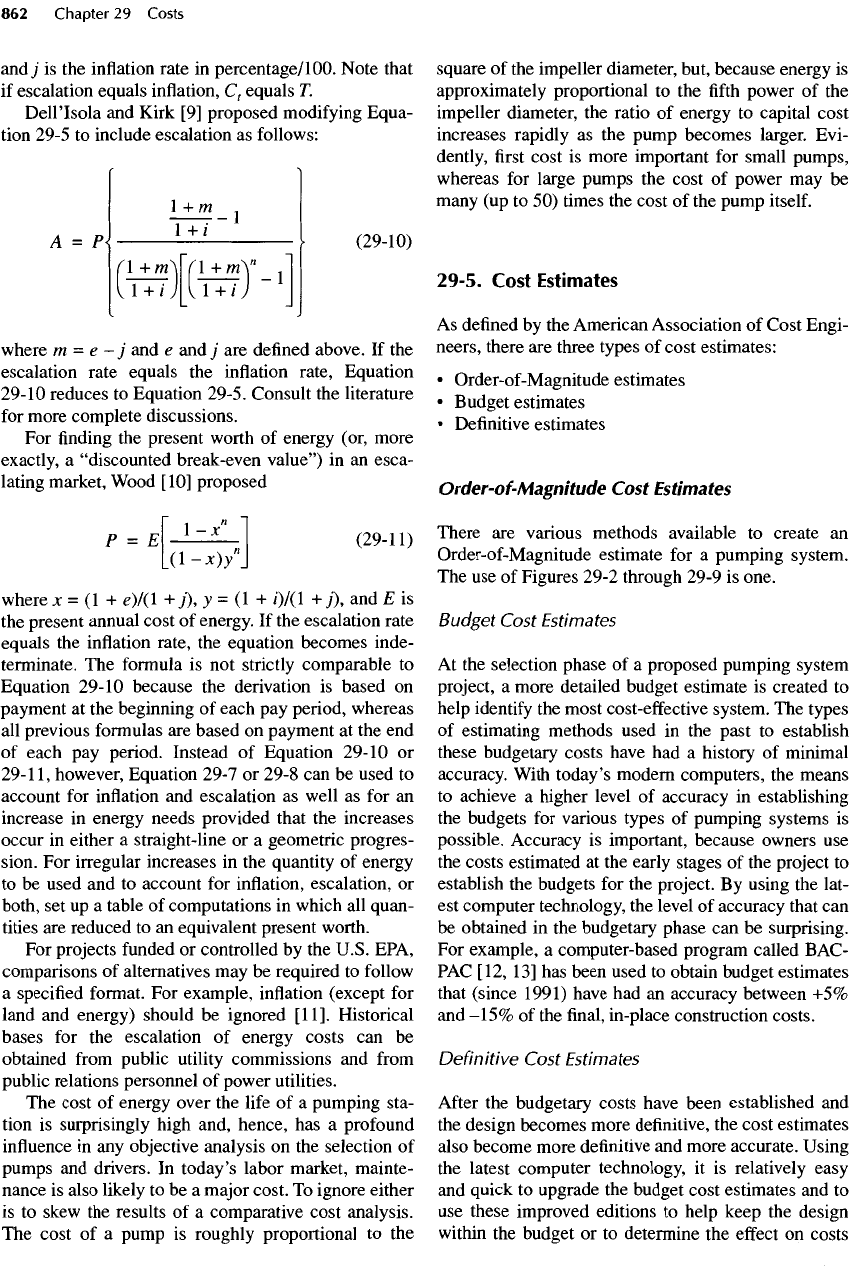

Geometric-Series

Factor

If

the

costs

or

quantities increase geometrically with

time,

the

total payments

for

each

period

are

• C at the end of

year

1

• aC at the end of

year

2

•

O

2

C

at the end of

year

3

•

a

n

~

l

C

at the end of

year

n.

The

geometric increase

(aC +

O

2

C

+

.

.

.

+

a

n

C)

can

be

converted

to

present worth

by

using

the

equation

n

,+

'\n~\

P

=

C

a

-

(

\

+l

)

(29-8)

a— 1

—

i

The

term

in

brackets

is

called

the

geometric-series,

compound-amount

factor

(gscaf).

The

present worth,

P,

can be

converted

to a

uniform annual amount,

A, by

means

of

Equation 29-5.

The

derivations

of

these equations, along

with

a

complete discussion

of

their use,

are

given

by

Taylor

[7].

Inflation

and

Escalation

Inflation

is the

decrease

in the

value

of

money. Escala-

tion

is the

increase

in

price

of a

particular commodity

of

concern, such

as

energy. Although both

are

com-

mon

experiences, there

is

some uncertainty about

how

they

should

be

treated

(if at

all)

in an

economic analy-

sis. Equations 29-2 through 29-6

can be

modified

for

inflation

or

inflation

can be

calculated

from

Equation

29-7

or

29-8,

but

predictions

of the

inflation

rate

are

apt

to be

faulty,

and,

in

many kinds

of

problems,

the

results

are not

altered

by

inflation.

If

the

escalation

of

energy costs equals

the

inflation

rate,

it,

too,

can be

ignored.

But if it is

expected

to

exceed

inflation,

there

is an

undue penalty

on a

more

costly

but

more

efficient

pump. White

et

al.

[8]

pro-

posed

the

concept

of

"constant-worth"

dollars

expressed

by the

equation

Cf

=

T(l+e)

(29

_

9)

(1+7')'

in

which

C

t

represents purchasing power

at

time

t

rela-

tive

to

year

O, T is the fixed,

constant-worth dollar

amount,

e is the

escalation rate

in

percentage/

100,

and;

is the

inflation

rate

in

percentage/

100.

Note that

if

escalation equals

inflation,

C

t

equals

T.

Dell'Isola

and

Kirk

[9]

proposed modifying Equa-

tion

29-5

to

include escalation

as

follows:

1

+m

.

A = P<

l+l

•

(29-10)

r

i+w

l[r

i+m

T-il

(i

+

ij[(i

+

ij

J

where

m-e-j

and e and

j

are

defined

above.

If the

escalation rate equals

the

inflation

rate, Equation

29-10

reduces

to

Equation 29-5. Consult

the

literature

for

more complete discussions.

For finding the

present worth

of

energy (or, more

exactly,

a

"discounted

break-even value")

in an

esca-

lating

market, Wood

[10]

proposed

1

n

1

P=E

(29-11)

Ld-*)/

J

where

x = (1 +

e)/(l

+y),

y = (1 +

/)/(!

+;'),

and E is

the

present annual cost

of

energy.

If the

escalation rate

equals

the

inflation

rate,

the

equation becomes inde-

terminate.

The

formula

is not

strictly comparable

to

Equation

29-10 because

the

derivation

is

based

on

payment

at the

beginning

of

each

pay

period, whereas

all

previous formulas

are

based

on

payment

at the end

of

each

pay

period. Instead

of

Equation 29-10

or

29-1

1,

however, Equation 29-7

or

29-8

can be

used

to

account

for

inflation

and

escalation

as

well

as for an

increase

in

energy needs provided that

the

increases

occur

in

either

a

straight-line

or a

geometric progres-

sion.

For

irregular increases

in the

quantity

of

energy

to be

used

and to

account

for

inflation,

escalation,

or

both,

set up a

table

of

computations

in

which

all

quan-

tities

are

reduced

to an

equivalent present worth.

For

projects

funded

or

controlled

by the

U.S. EPA,

comparisons

of

alternatives

may be

required

to

follow

a

specified

format.

For

example,

inflation

(except

for

land

and

energy) should

be

ignored

[U].

Historical

bases

for the

escalation

of

energy costs

can be

obtained

from

public

utility

commissions

and

from

public

relations personnel

of

power utilities.

The

cost

of

energy over

the

life

of a

pumping sta-

tion

is

surprisingly high and, hence,

has a

profound

influence

in any

objective analysis

on the

selection

of

pumps

and

drivers.

In

today's labor market, mainte-

nance

is

also likely

to be a

major

cost.

To

ignore either

is to

skew

the

results

of a

comparative cost analysis.

The

cost

of a

pump

is

roughly proportional

to the

square

of the

impeller diameter, but, because energy

is

approximately proportional

to the fifth

power

of the

impeller

diameter,

the

ratio

of

energy

to

capital cost

increases rapidly

as the

pump becomes larger. Evi-

dently,

first

cost

is

more important

for

small pumps,

whereas

for

large pumps

the

cost

of

power

may be

many

(up to 50)

times

the

cost

of the

pump

itself.

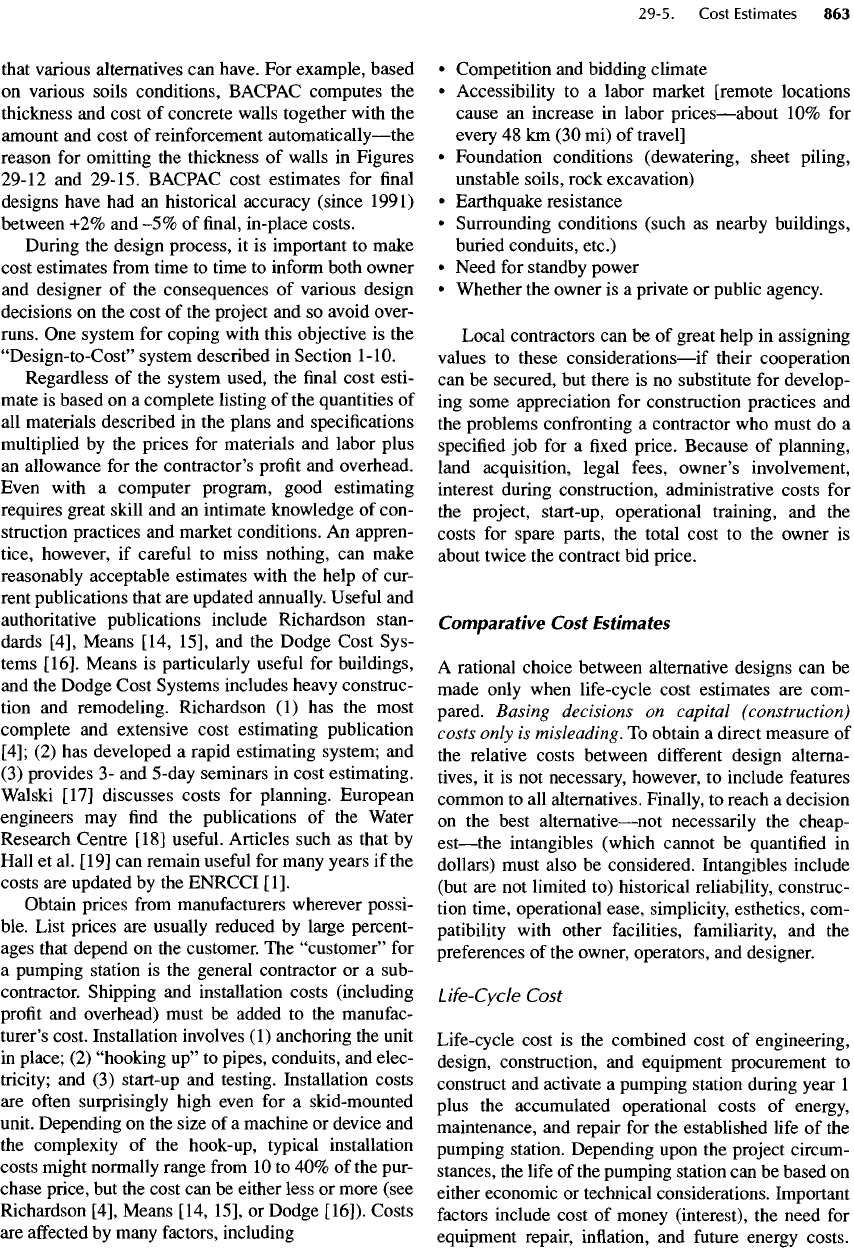

29-5. Cost

Estimates

As

defined

by the

American Association

of

Cost Engi-

neers,

there

are

three

types

of

cost

estimates:

•

Order-of-Magnitude estimates

•

Budget

estimates

•

Definitive estimates

Order-of-Magnitude

Cost

Estimates

There

are

various methods available

to

create

an

Order-of-Magnitude

estimate

for a

pumping system.

The use of

Figures 29-2 through 29-9

is

one.

Budget Cost Estimates

At

the

selection phase

of a

proposed pumping system

project,

a

more detailed budget estimate

is

created

to

help

identify

the

most cost-effective system.

The

types

of

estimating methods used

in the

past

to

establish

these budgetary costs have

had a

history

of

minimal

accuracy.

With today's modern computers,

the

means

to

achieve

a

higher level

of

accuracy

in

establishing

the

budgets

for

various types

of

pumping systems

is

possible. Accuracy

is

important, because owners

use

the

costs estimated

at the

early stages

of the

project

to

establish

the

budgets

for the

project.

By

using

the

lat-

est

computer technology,

the

level

of

accuracy that

can

be

obtained

in the

budgetary phase

can be

surprising.

For

example,

a

computer-based program called BAC-

PAC

[12,

13] has

been used

to

obtain budget estimates

that

(since

1991)

have

had an

accuracy between

+5%

and

-15%

of the final,

in-place

construction costs.

Definitive

Cost Estimates

After

the

budgetary costs have been established

and

the

design becomes more

definitive,

the

cost estimates

also become more

definitive

and

more accurate. Using

the

latest computer technology,

it is

relatively easy

and

quick

to

upgrade

the

budget cost estimates

and to

use

these improved editions

to

help keep

the

design

within

the

budget

or to

determine

the

effect

on

costs

that

various alternatives

can

have.

For

example, based

on

various soils conditions, BACPAC computes

the

thickness

and

cost

of

concrete

walls together with

the

amount

and

cost

of

reinforcement

automatically

—

the

reason

for

omitting

the

thickness

of

walls

in

Figures

29-12

and

29-15.

BACPAC

cost

estimates

for final

designs have

had an

historical accuracy (since 1991)

between

+2% and -5% of final,

in-place

costs.

During

the

design process,

it is

important

to

make

cost estimates

from

time

to

time

to

inform

both owner

and

designer

of the

consequences

of

various design

decisions

on the

cost

of the

project

and so

avoid over-

runs.

One

system

for

coping with this objective

is the

"Design-to-Cost"

system described

in

Section

1-10.

Regardless

of the

system used,

the final

cost esti-

mate

is

based

on a

complete listing

of the

quantities

of

all

materials described

in the

plans

and

specifications

multiplied

by the

prices

for

materials

and

labor plus

an

allowance

for the

contractor's

profit

and

overhead.

Even with

a

computer program, good estimating

requires great skill

and an

intimate knowledge

of

con-

struction

practices

and

market conditions.

An

appren-

tice, however,

if

careful

to

miss nothing,

can

make

reasonably acceptable estimates with

the

help

of

cur-

rent

publications

that

are

updated annually.

Useful

and

authoritative publications include Richardson stan-

dards [4], Means [14, 15],

and the

Dodge Cost Sys-

tems

[16].

Means

is

particularly

useful

for

buildings,

and

the

Dodge Cost Systems includes

heavy

construc-

tion

and

remodeling. Richardson

(1) has the

most

complete

and

extensive cost estimating publication

[4];

(2) has

developed

a

rapid estimating system;

and

(3)

provides

3- and

5-day seminars

in

cost estimating.

Walski

[17] discusses costs

for

planning. European

engineers

may find the

publications

of the

Water

Research Centre [18]

useful.

Articles such

as

that

by

Hall

et

al.

[19]

can

remain

useful

for

many

years

if the

costs

are

updated

by the

ENRCCI

[I].

Obtain prices

from

manufacturers wherever possi-

ble. List prices

are

usually

reduced

by

large percent-

ages

that

depend

on the

customer.

The

"customer"

for

a

pumping station

is the

general contractor

or a

sub-

contractor. Shipping

and

installation costs (including

profit

and

overhead)

must

be

added

to the

manufac-

turer's cost. Installation involves

(1)

anchoring

the

unit

in

place;

(2)

"hooking

up" to

pipes, conduits,

and

elec-

tricity;

and (3)

start-up

and

testing. Installation costs

are

often

surprisingly high even

for a

skid-mounted

unit.

Depending

on the

size

of a

machine

or

device

and

the

complexity

of the

hook-up, typical installation

costs might normally range

from

10 to 40% of the

pur-

chase

price,

but the

cost

can be

either less

or

more (see

Richardson [4], Means [14, 15],

or

Dodge

[16]).

Costs

are

affected

by

many factors, including

•

Competition

and

bidding climate

•

Accessibility

to a

labor market [remote

locations

cause

an

increase

in

labor

prices

—

about

10% for

every

48 km (30 mi) of

travel]

•

Foundation conditions

(dewatering,

sheet piling,

unstable

soils,

rock excavation)

•

Earthquake resistance

•

Surrounding conditions (such

as

nearby buildings,

buried conduits, etc.)

•

Need

for

standby power

•

Whether

the

owner

is a

private

or

public agency.

Local contractors

can be of

great help

in

assigning

values

to

these

considerations

—

if

their cooperation

can

be

secured,

but

there

is no

substitute

for

develop-

ing

some appreciation

for

construction practices

and

the

problems confronting

a

contractor

who

must

do a

specified

job for a fixed

price.

Because

of

planning,

land

acquisition, legal

fees,

owner's involvement,

interest during construction, administrative costs

for

the

project, start-up, operational training,

and the

costs

for

spare parts,

the

total cost

to the

owner

is

about twice

the

contract

bid

price.

Comparative

Cost

Estimates

A

rational choice between alternative designs

can be

made only when life-cycle cost estimates

are

com-

pared. Basing decisions

on

capital

(construction)

costs

only

is

misleading.

To

obtain

a

direct measure

of

the

relative costs between

different

design alterna-

tives,

it is not

necessary, however,

to

include features

common

to all

alternatives.

Finally,

to

reach

a

decision

on

the

best

alternative

—

not

necessarily

the

cheap-

est

—

the

intangibles (which cannot

be

quantified

in

dollars) must also

be

considered. Intangibles include

(but

are not

limited

to)

historical reliability, construc-

tion time, operational

ease,

simplicity, esthetics, com-

patibility with other facilities,

familiarity,

and the

preferences

of the

owner, operators,

and

designer.

Life-Cycle

Cost

Life-cycle

cost

is the

combined cost

of

engineering,

design, construction,

and

equipment procurement

to

construct

and

activate

a

pumping station during year

1

plus

the

accumulated operational costs

of

energy,

maintenance,

and

repair

for the

established

life

of the

pumping

station. Depending upon

the

project circum-

stances,

the

life

of the

pumping station

can be

based

on

either economic

or

technical considerations. Important

factors

include cost

of

money (interest),

the

need

for

equipment repair,

inflation,

and

future

energy costs.

The

initial cost together with each

of the

annual costs

(corrected

to

present worth value

by

means

of the

equations

in

Section

29-4)

yields

the

total

life-cycle

cost. Although

the

life-cycle cost

may not be

exact,

it

is the

only

way in

which

the

relationship between dif-

ferent

alternatives

can be

objectively assessed.

Unfortunately,

owners

are

seldom willing

to pay for

a

life-cycle cost analysis that

is

truly

complete,

and it is

customary

to

consider capital costs only and, even

so, to

ignore

the

effects

of the

project

on the

cost

of the

whole

system.

(For example, savings using

C/S

instead

of V/S

pumping

may

stress

—

and

hence increase

the

cost

—

of

the

treatment process downstream.)

The

designer,

as a

consequence,

is

often

required

to

guess

at

answers,

and

such

guesses

can be

misleading.

In

Example 29-1

of the

original

(1989)

edition

of

this book, stations with con-

stant

speed (C/S), variable speed (V/S) with AFDs,

and

V/S

with eddy-current

couplings

for

pump drivers were

compared

for an 880 L/s (20

Mgal/d)

wastewater pump-

ing

station.

In

view

of the

inefficiency

of

eddy-current

couplings,

the

results were surprising.

The

comparative

costs were 126, 107,

and 100

respectively. Thus,

the

lowest cost

was for

eddy-current couplings.

The

results

might

have been

different

if

energy costs

had

been

higher than those

assumed

—

essentially

a

peak power

rate

of

6.37

eTkW

• h and an

off-peak

rate

of

3.15

0/kW

•

h.

Nowadays,

the

prices

of

eddy-current couplings

have

increased whereas

the

prices

of

AFDs have

decreased,

so in

today's

market,

the

AFDs would proba-

bly

be the

most cost

effective.

Example

29-1

Life-Cycle Cost Comparison

of

Three Alternative Wastewater Pumping Stations

Two

common problems today involve:

(1)

the

choice between using

a few

large pumps

and

more smaller ones (with

the

consequent

increase

in

piping

and

space requirement)

and (2) the

choice between using

C/S and V/S

drives. Both problems

as

applied

to

submersible pumps

are

illustrated

in

Example

29-1.

The

example

is

hypothetical,

but the

life-cycle cost analyses

are

realistic

and

supportable.

Three

options

are

compared:

•

Three

V/S

pumps

(2

duty,

1

standby)

of

equal size.

•

Three

C/S

pumps

of the

above size plus

a

smaller jockey pump.

•

Three

C/S

pumps

of

equal size.

To

avoid tedious repetition

in

tables, this example

is

worked only

in

U.S. customary units.

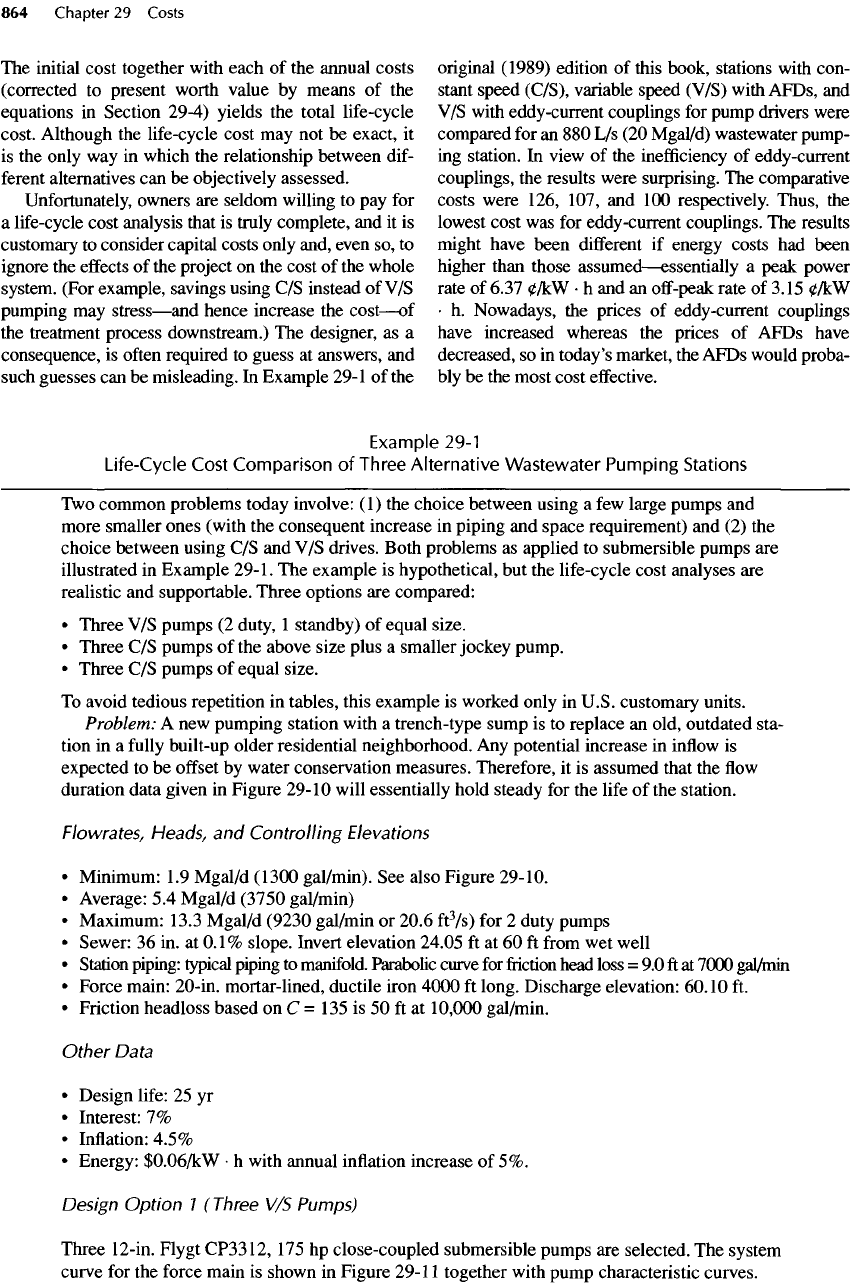

Problem:

A new

pumping station with

a

trench-type sump

is to

replace

an

old, outdated sta-

tion

in a

fully

built-up older residential neighborhood.

Any

potential increase

in

inflow

is

expected

to be

offset

by

water conservation measures. Therefore,

it is

assumed that

the flow

duration

data given

in

Figure

29-10

will essentially hold steady

for the

life

of the

station.

Flowrates,

Heads,

and

Controlling

Elevations

•

Minimum:

1.9

Mgal/d (1300

gal/min).

See

also Figure 29-10.

•

Average:

5.4

Mgal/d (3750 gal/min)

•

Maximum: 13.3 Mgal/d (9230 gal/min

or

20.6

ft

3

/s)

for 2

duty

pumps

•

Sewer:

36 in. at

0.1%

slope. Invert elevation

24.05

ft at 60 ft

from

wet

well

•

Station piping: typical piping

to

manifold.

Parabolic

curve

for

friction

head loss

= 9.0 ft at

7000

gal/min

•

Force main: 20-in. mortar-lined, ductile iron

4000

ft

long. Discharge elevation:

60.10

ft.

•

Friction headloss based

on C =

135

is 50 ft at

10,000

gal/min.

Other Data

•

Design

life:

25 yr

•

Interest:

7%

•

Inflation:

4.5%

•

Energy:

$0.06/kW

• h

with annual

inflation

increase

of

5%.

Design

Option

1

(Three

V/S

Pumps)

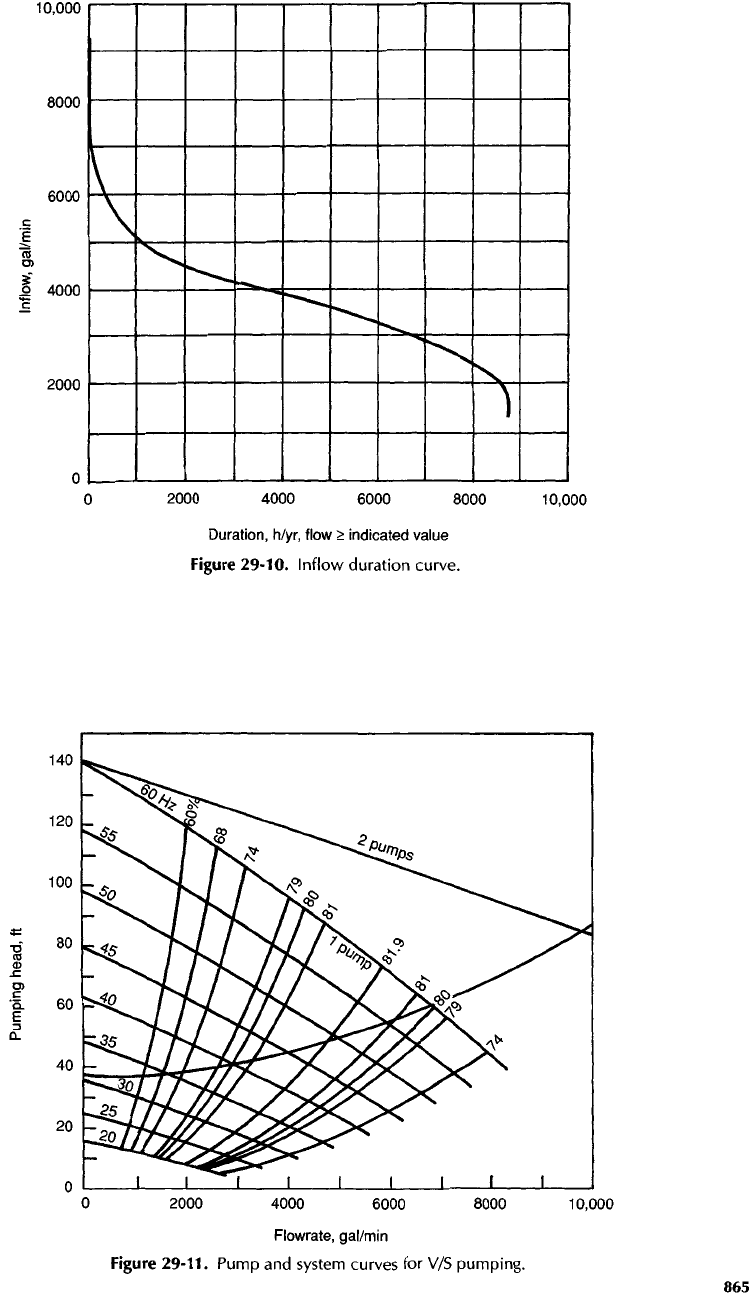

Three

12-in.

Flygt

CP3312,175

hp

close-coupled submersible pumps

are

selected.

The

system

curve

for the

force main

is

shown

in

Figure

29-11

together with pump characteristic curves.

Figure

29-10. Inflow duration curve.

Figure

29-11.

Pump

and

system curves

for V/S

pumping.

Station piping headlosses

for a

pump

are

assumed

to

follow

a

parabola

to a

loss

of 1

ft

at

a

dis-

charge

of

6000

gal/min.

To

make sure that

the

station

can

meet

its

requirements,

the H-W C is

often

considered

to

vary

between

145 or 150 and

120.

For a

life-cycle cost analysis, however,

the use of

excessive

safety

factors

is

misleading,

and the

best—not

the

safest—values

are

needed,

so the

chosen

value

of C is

135.

Two

pumps together

can

discharge

9860

gal/min

at

89.5

ft of

head whereas

a

single pump

can

discharge

6790

gal/min

at

69.6

ft of

head.

Each pump

is

equipped with

a

top-of-the-line

pulse width modulated (PWM) type

of AFD to

produce

the

highest drive

efficiencies

available

to

date. Because

of

their sensitivity

to

heat,

fumes,

and

dust,

the

AFDs

are

housed

in a

small air-conditioned building where incoming

air is

filtered to

remove

all

dust

and

fumes,

particularly

H

2

S.

Motors

controlled

by AF

converters

are

subjected

to

severe service

and are

consequently derated. Despite

the

derating, they require

more maintenance than

do

motors

for C/S

pumps.

The

principal advantage

of V/S

pumping

is

that discharge equals

inflow

at all

times,

and

thus

there

are no

sudden changes

of the

inflow

to the

treatment

plant—an

advantage that

may be

overwhelming

or

negligible depending

on the

relative sizes

of

pumping station

and

treatment

plant

and the

sensitivity

of the

treatment plant facilities

to

shock loads.

The

other advantages

are

the

increased operational

flexibility, the

reduced energy consumption,

the

smaller size

of the wet

well,

and a

shallower excavation

if the wet

well must

be

self-cleaning.

The

disadvantages

are the

substantial

costs

of the

AFDs,

the

increased control system complexity,

the

potential problems

with

harmonics

and

power quality, plus

the

increased maintenance both

for the AF

converters

themselves

and for the

air-conditioning unit required

to

protect

them

from

dust,

fumes,

and

heat.

Furthermore, AFDs require highly skilled personnel

for

servicing

and

repairs. Overall station

reliability

is

reduced somewhat,

but

AFDs have

become

more dependable

in

recent years. High-

quality equipment

is

reliable

when well maintained

and

housed

in an

air-conditioned space.

The

design

follows

the

guidelines

in

Chapter

12. At an

entrance velocity

of 5.5

ft/s,

the

diam-

eter

of the

suction bell

for

6800

gal/min (Figure

29-11)

would

be

1.88

ft, but the

next standard

flange

and

flare is

1.96

ft in

diameter.

The

maximum entrance velocity

is

5.03 ft/s.

The

trench

width

is 2 D =

3.92

ft. and the

depth

is 2 D + floor

clearance

=

4.90

ft.

Submergence required

(Equation 12-1)

is 4.8 ft. The top of the

trench

was set

0.95

ft

below

the

invert

of the

sewer

so

that

at

neither peak

inflow

nor at

half

the

peak

inflow

(at a

lower elevation,

of

course) would

the

average velocity

in the wet

well above

the

trench

and

around

the

motors exceed

1.0

ft/s.

The

actual submergence

is

about

5.2 ft at LWL and 7.5 ft at

HWL.

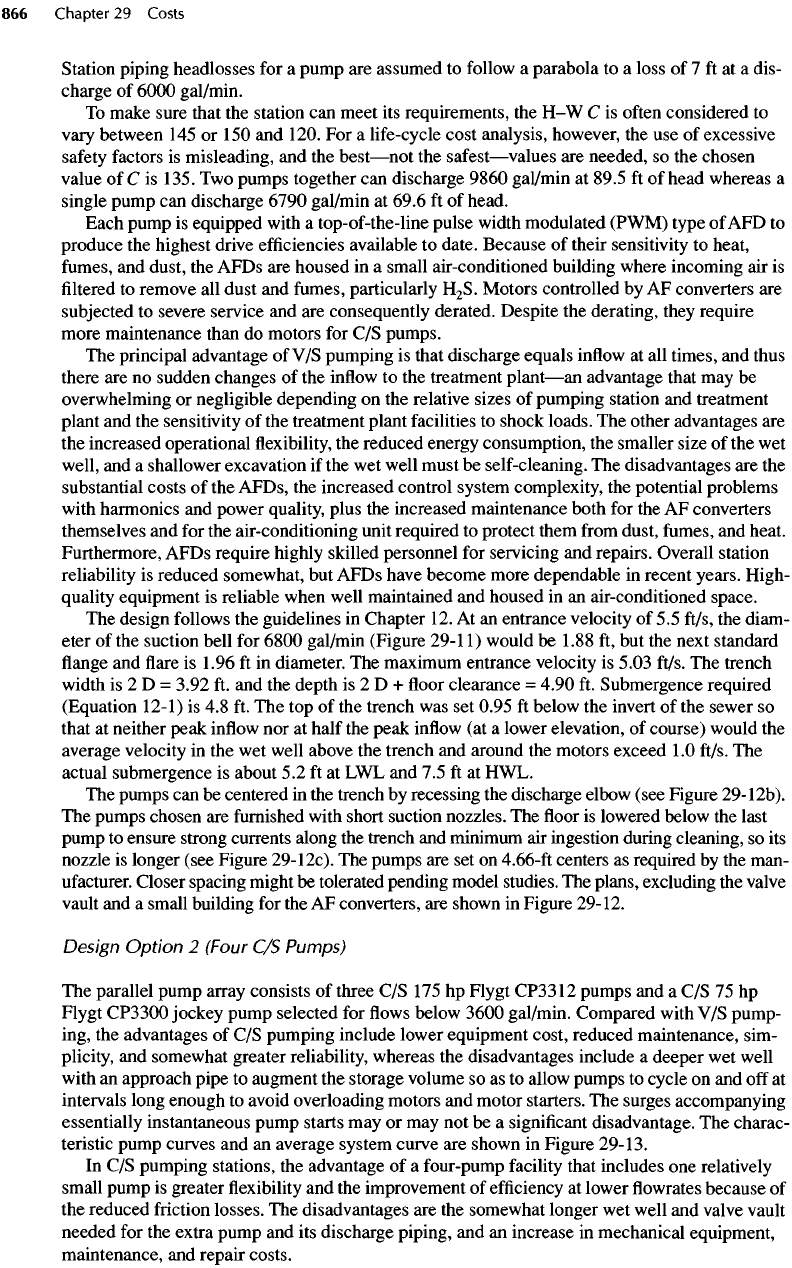

The

pumps

can be

centered

in the

trench

by

recessing

the

discharge elbow (see Figure

29-12b).

The

pumps chosen

are

furnished

with short suction nozzles.

The floor is

lowered below

the

last

pump

to

ensure strong currents along

the

trench

and

minimum

air

ingestion

during cleaning,

so its

nozzle

is

longer (see Figure

29-12c).

The

pumps

are set on

4.66-ft

centers

as

required

by the

man-

ufacturer.

Closer spacing might

be

tolerated pending model studies.

The

plans, excluding

the

valve

vault

and a

small building

for the AF

converters,

are

shown

in

Figure

29-12.

Design

Option

2

(Four

C/S

Pumps)

The

parallel pump array consists

of

three

C/S 175 hp

Flygt

CP3312

pumps

and a C/S 75 hp

Flygt

CP3300

jockey pump

selected

for flows

below

3600

gal/min. Compared with

V/S

pump-

ing,

the

advantages

of C/S

pumping include lower equipment cost, reduced maintenance, sim-

plicity,

and

somewhat greater reliability, whereas

the

disadvantages include

a

deeper

wet

well

with

an

approach pipe

to

augment

the

storage volume

so as to

allow pumps

to

cycle

on and

off

at

intervals long enough

to

avoid overloading motors

and

motor starters.

The

surges accompanying

essentially instantaneous pump starts

may or may not be a

significant

disadvantage.

The

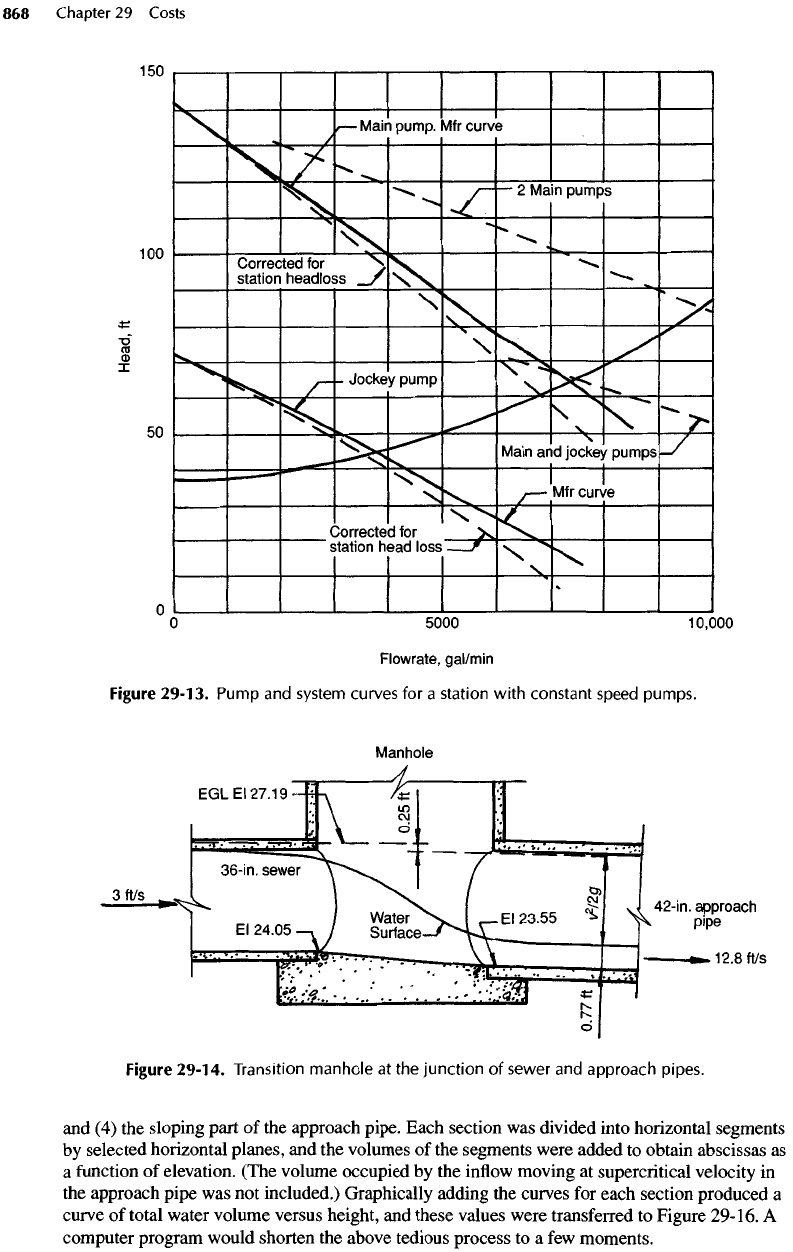

charac-

teristic pump curves

and an

average system curve

are

shown

in

Figure

29-13.

In

C/S

pumping stations,

the

advantage

of a

four-pump facility that includes

one

relatively

small pump

is

greater

flexibility and the

improvement

of

efficiency

at

lower

flowrates

because

of

the

reduced

friction

losses.

The

disadvantages

are the

somewhat

longer

wet

well

and

valve vault

needed

for the

extra pump

and its

discharge piping,

and an

increase

in

mechanical equipment,

maintenance,

and

repair

costs.

Figure

29-12.

Plans

for a

pumping

station

with

three

V/S

pumps,

(a)

Plan

at

Elev.

28.0

ft; (b)

Section

A-A;

(c)

Section

B-B.

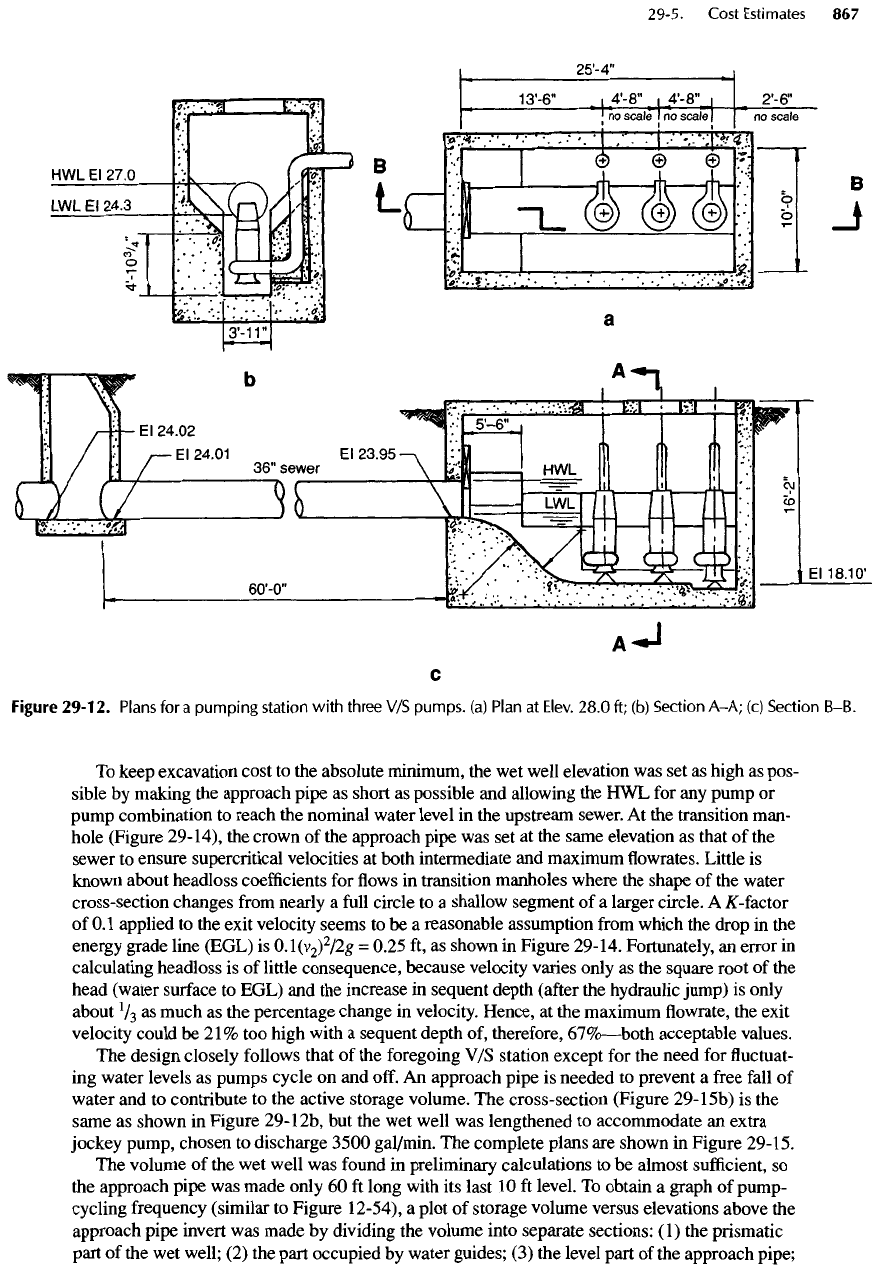

To

keep excavation cost

to the

absolute minimum,

the wet

well elevation

was set as

high

as

pos-

sible

by

making

the

approach pipe

as

short

as

possible

and

allowing

the HWL for any

pump

or

pump

combination

to

reach

the

nominal water level

in the

upstream sewer.

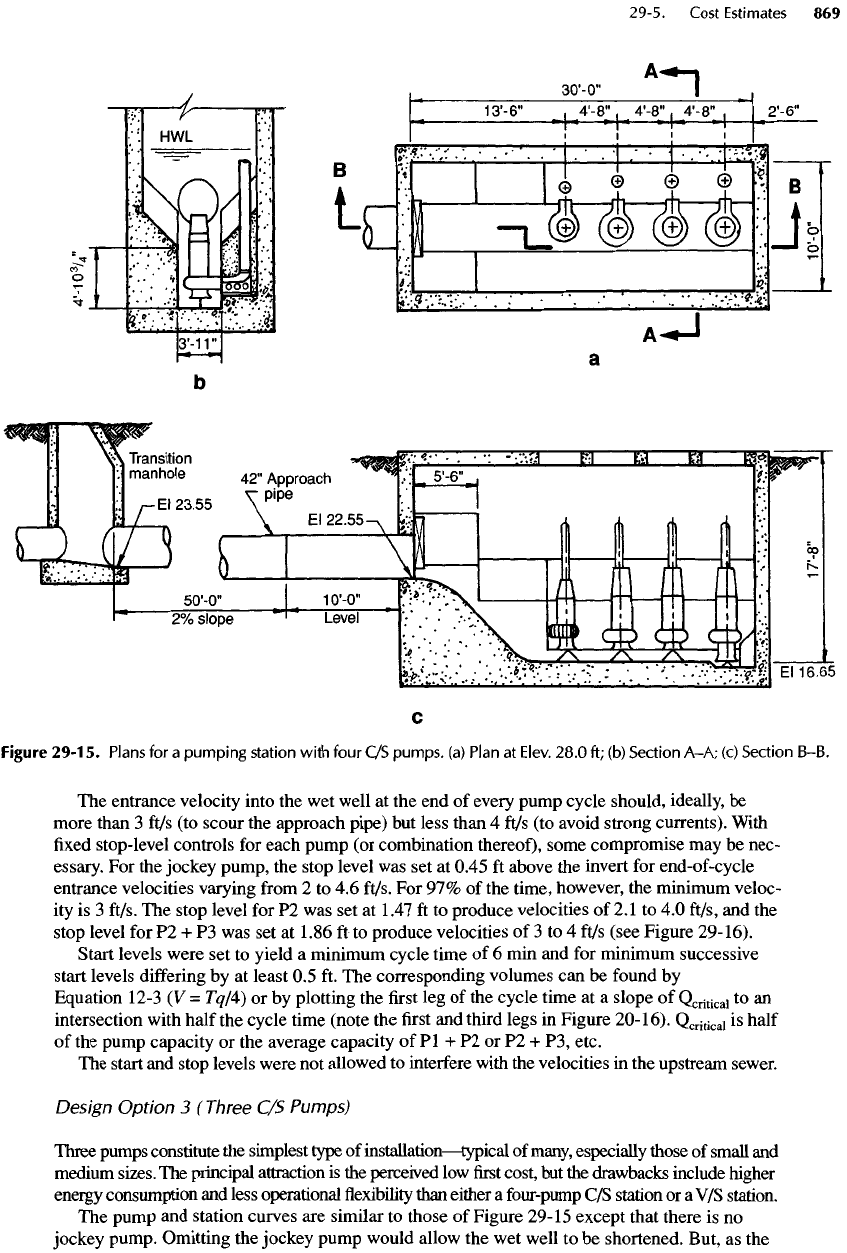

At the

transition man-

hole (Figure 29-14),

the

crown

of the

approach pipe

was set at the

same elevation

as

that

of the

sewer

to

ensure supercritical velocities

at

both intermediate

and

maximum

flowrates.

Little

is

known

about

headless

coefficients

for flows in

transition manholes where

the

shape

of the

water

cross-section changes

from

nearly

a

full

circle

to a

shallow segment

of a

larger circle.

A

K-factor

of

0.1

applied

to the

exit velocity seems

to be a

reasonable assumption

from

which

the

drop

in the

energy

grade line (EGL)

is

0.1(v

2

)

2

/2g

=

0.25

ft, as

shown

in

Figure 29-14. Fortunately,

an

error

in

calculating

headless

is of

little consequence, because velocity varies only

as the

square root

of the

head (water

surface

to

EGL)

and the

increase

in

sequent depth

(after

the

hydraulic jump)

is

only

about

V

3

as

much

as the

percentage change

in

velocity. Hence,

at the

maximum

flowrate, the

exit

velocity could

be

21%

too

high with

a

sequent depth

of,

therefore,

67%—both

acceptable values.

The

design

closely

follows that

of the

foregoing

V/S

station except

for the

need

for fluctuat-

ing

water levels

as

pumps cycle

on and

off.

An

approach pipe

is

needed

to

prevent

a

free

fall

of

water

and to

contribute

to the

active storage volume.

The

cross-section (Figure

29-15b)

is the

same

as

shown

in

Figure

29-12b,

but the wet

well

was

lengthened

to

accommodate

an

extra

jockey pump, chosen

to

discharge

3500

gal/min.

The

complete

plans

are

shown

in

Figure

29-15.

The

volume

of the wet

well

was

found

in

preliminary calculations

to be

almost

sufficient,

so

the

approach pipe

was

made only

60 ft

long

with

its

last

10 ft

level.

To

obtain

a

graph

of

pump-

cycling

frequency

(similar

to

Figure 12-54),

a

plot

of

storage volume versus elevations above

the

approach

pipe

invert

was

made

by

dividing

the

volume into separate

sections:

(1) the

prismatic

part

of the wet

well;

(2) the

part occupied

by

water guides;

(3) the

level part

of the

approach pipe;

Figure

29-14.

Transition

manhole

at the

junction

of

sewer

and

approach

pipes.

and

(4) the

sloping part

of the

approach

pipe.

Each section

was

divided into horizontal segments

by

selected horizontal planes,

and the

volumes

of the

segments were added

to

obtain abscissas

as

a

function

of

elevation. (The volume occupied

by the

inflow

moving

at

supercritical velocity

in

the

approach pipe

was not

included.) Graphically adding

the

curves

for

each section produced

a

curve

of

total water volume versus height,

and

these values were transferred

to

Figure 29-16.

A

computer program would shorten

the

above tedious process

to a few

moments.

Figure

29-13.

Pump

and

system curves

for a

station

with

constant speed pumps.

Figure

29-15.

Plans

for a

pumping

station

with

four

C/S

pumps,

(a)

Plan

at

Elev.

28.0

ft; (b)

Section

A-A;

(c)

Section

B-B.

The

entrance velocity into

the wet

well

at the end of

every pump cycle should, ideally,

be

more than

3

ft/s

(to

scour

the

approach pipe)

but

less than

4

ft/s

(to

avoid strong currents). With

fixed

stop-level controls

for

each pump

(or

combination thereof), some compromise

may be

nec-

essary.

For the

jockey pump,

the

stop level

was set at

0.45

ft

above

the

invert

for

end-of-cycle

entrance velocities varying

from

2 to 4.6

ft/s.

For 97% of the

time, however,

the

minimum veloc-

ity

is 3

ft/s.

The

stop level

for P2 was set at

1.47

ft to

produce velocities

of

2.1

to 4.0

ft/s,

and the

stop level

for P2 + P3 was set at

1.86

ft to

produce velocities

of 3 to 4

ft/s (see Figure

29-16).

Start levels were

set to

yield

a

minimum cycle time

of 6 min and for

minimum successive

start levels

differing

by at

least

0.5 ft. The

corresponding volumes

can be

found

by

Equation

12-3

(V =

Tq/4)

or by

plotting

the first leg of the

cycle time

at a

slope

of

Q

critical

to an

intersection with half

the

cycle time (note

the first and

third legs

in

Figure

20-16).

Q

critical

is

half

of

the

pump capacity

or the

average capacity

of Pl + P2 or P2 + P3,

etc.

The

start

and

stop levels were

not

allowed

to

interfere with

the

velocities

in the

upstream sewer.

Design

Option

3

(Three

C/S

Pumps)

Three pumps constitute

the

simplest type

of

installation—typical

of

many,

especially those

of

small

and

medium

sizes.

The

principal attraction

is the

perceived

low first

cost,

but the

drawbacks include higher

energy

consumption

and

less operational

flexibility

than

either

a

four-pump

C/S

station

or a V/S

station.

The

pump

and

station curves

are

similar

to

those

of

Figure

29-15

except that there

is no

jockey pump. Omitting

the

jockey pump would allow

the wet

well

to be

shortened. But,

as the