Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Rouge. Thousands fled to Thailand, and many were even-

tually granted asylum in third countries. Vietnam withdrew

troops in 1989, paving the way for United Nations–spon-

sored elections under a new constitutional monarchy.

Khmer Rouge rebels continued to violently protest the gov-

ernment until their leader broke away to support the monar-

chy in 1996.

In the immediate aftermath of the Vietnam War, per-

haps as many as 8,000 Cambodians eventually found their

way to the United States before the end of the decade. The

first widespread resettlement of Cambodian refugees in the

United States began, however, in 1979. Most were resettled

by voluntary agencies (VOLAGs) affiliated with churches

that had first been organized in 1975 in order to deal with

the massive influx of Vietnamese refugees. The VOLAGs

were contracted by the U.S. government to teach English

and locate sponsors who would assume responsibility for

up to two years. During the 1980s, about 114,000 Cambo-

dian refugees were resettled in the United States, with almost

70 percent coming between 1980 and 1984. The majority

of refugees in both the United States and Canada were

poorly educated and from rural areas. As a tenuous stability

returned to Cambodia during the 1990s, immigration lev-

eled off, averaging a little less than 2,000 per year between

1992 and 2002.

It is estimated that prior to 1975 there were only 200

Cambodians in Canada. Between 1975 and 1980 some stu-

dents, diplomats, and businessmen, left in limbo by the

diplomatic isolation of their country under the Khmer

regime, were granted permanent resident status. Most Cam-

bodian Canadians, however, were refugees admitted during

the 1980s and early 1990s, when Canada accepted more

than 18,000. The largest number entered in 1980, when

3,269 were resettled. Of the 18,740 Cambodians in Canada

in 2001, 11,240 came between 1981 and 1990, and only

3,315 between 1991 and 2001.

Further Reading

Adelman, Howard. Canada and the I

ndochinese Refugees. Regina,

Canada: L. A. Weigl Educational Associates, 1982.

Chan, Sucheng, ed. Not Just Victims: Conversations with Cambodian

Community Leaders in the United States. Urbana: University of

Illinois P

r

ess, 2003.

Dorais, Louis-Jacques. The Cambodians, Laotians and Vietnamese in

Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 2000.

Dorais, Louis-J

acques, Lise Pilon, and Huy Nguyen. Exile in a Cold

Land. New Haven, Conn.:

Y

ale University Press, 1987.

Ebihara, May M., Carol A. Mortland, and Judy L. Ledgerwood, eds.

Cambodian Culture since 1975: Homeland and Exile. Ithaca, N.Y.:

Cornell University Press, 1994.

Haines, David W., ed. Refugees as Immigrants: Cambodians, Laotians,

and

V

ietnamese in America. Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Little-

field, 1989.

Hein, Jeremy. From Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia: A Refugee Experience

in the U

nited States. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995.

McLellan, Janet. Cambodian Refugees in O

ntario: An Evaluation of

Resettlement and Adaptation. North York, Canada: York Lanes

Pr

ess, 1995.

Mortland, Carol A. “Khmer.” In Case S

tudies in Diversity: Refugees in

A

merica in the 1990s. Ed. David W. Haines. Westport, Conn.:

Praeger

, 1997.

O’Connor, Valerie. The I

ndochina Refugee Dilemma. Baton Rouge:

Louisiana S

tate University Press, 1990.

Rumbaut, Rubén G. “A Legacy of War: Refugees from Vietnam, Laos

and Cambodia.” In Origins and D

estinies: I

mmigration, Race and

Ethnicity in America. Eds. Silvia Pedraza and Rubén G. Rumbaut.

Belmont, Calif

.: Wadsworth, 1996.

Smith-Hefner, Nancy J. Khmer American: Identity and Moral Educa-

tion in a Diasporic Community

. B

erkeley: University of California

Pr

ess, 1999.

Welaratna, Usha. Beyond the Killing Fields: Voices of Nine Cambodian

S

ur

vivors in America. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press,

1993.

Canada—immigration survey and policy

overview

Canada has frequently been referred to as “a nation of immi-

grants,” though the percentage of immigrants has always

been less than the term would suggest. In its peak periods

during the 1860s and the first decade of the 20th century, the

percentage was less than one-quarter of the population and

since 1940 has stabilized between 16 and 18 percent. In

2001, the Canadian population of just under 30 million was

18 percent immigrant. Another consistent, related theme is

the persistence of outmigration, mostly to the United States.

With a few exceptions, most periods of Canadian history saw

more people leaving than coming, or only modest gains in

net immigration. Finally, Canadian immigration policy was

until the 1970s largely exclusionary, heavily favoring immi-

grants from Britain, the United States, and western Europe.

Canada occupies 3,851,809 square miles of the north-

ern reaches of the North American continent, making it by

area the second largest country in the world. Most of

Canada lies above the 49th parallel, northward to the Arctic

Ocean and extending from the Atlantic Ocean in the east

to the Pacific Ocean in the west. Difficult terrain and harsh

winters have kept the Canadian population relatively small

throughout its history. Parts of modern Canada were visited

by the Vikings, around 1000, though they left no perma-

nent mark on the culture. J

OHN

C

ABOT

(sailing for En-

gland, 1497) and J

ACQUES

C

ARTIER

(French, 1534) were

the next Europeans to explore the Atlantic coasts. Their

claims on behalf of their respective countries laid the foun-

dation for an intense rivalry for control of Canada, one of

the hallmarks of international affairs from 1604 to 1763.

British victory in the S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

(1756–63) guar-

anteed the predominance of British culture patterns, but

more than 150 years of French settlement left an indelible

mark, particularly in the province of Q

UEBEC

.

44 CANADA—IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

Settlement of St. Croix Island (1604) and Quebec

(1608) by Frenchmen Samuel de Champlain and Pierre du

Gua, sieur de Monts, marked the beginning of colonization

of the lands claimed for France by Cartier. Within N

EW

F

RANCE

there were three areas of settlement: A

CADIA

, the

mainland and island areas along the Atlantic coast;

L

OUISIANA

, the lands drained by the Mississippi, Missouri,

and Ohio river valleys; and Canada, the lands on either side

of the St. Lawrence Seaway and just north of the Great

Lakes. Among these, only Canada, with the important set-

tlements of Quebec and Montreal, developed a significant

population. A harsh climate and continual threats from the

British and the Iroquois made it difficult for private compa-

nies to attract settlers to Canada; only about 9,000 came

during the entire period of French control. The principal

economic activity was the fur trade, which was incompatible

with family emigration and therefore left New France

sparsely populated and vulnerable to the more rapidly

expanding British. In 1663, Louis XIV (r. 1643–1715)

made New France a royal colony but was only moderately

successful at bringing in more colonists.

At the end of the Seven Years’ War, Canada’s French

population of some 70,000 was brought under control of

the British Crown, which organized the most populous areas

as part of the colony of Quebec. At first administering the

region under British law and denying Catholics important

rights, the British further alienated their new citizens. Then,

in an attempt to win support of Quebec’s French-speaking

population, Governor Guy Carleton, in 1774, persuaded

the British parliament to pass the Q

UEBEC

A

CT

, which guar-

anteed religious freedom to Catholics, reinstated French

civil law, and extended the southern border of the province

to the Ohio River, incorporating lands claimed by Virginia

and Massachusetts. This marked the high point of escalating

tensions with the thirteen colonies to the south that would

explode into the American Revolution (1775–83) and even-

tually result in the loss of the colonies and trans-Appalachian

regions south of the Great Lakes.

With the loss of the thirteen colonies came the migra-

tion to Canada of 40,000–50,000 United Empire Loyalists,

who had refused to take up arms against the British Crown

and were thus resettled at government expense, most with

grants of land in N

OVA

S

COTIA

,N

EW

B

RUNSWICK

, and

western Quebec. The special provisions of the Quebec Act

that had preserved the culture of the French and encour-

aged their loyalty, angered the new English-speaking

American colonists. As a result, the British government

divided the region into two colonies by the Constitutional

Act of 1791. Lower Canada, roughly the modern province

of Quebec, included most of the French-speaking popula-

tion. There, government was based on French civil law,

Catholicism, and the seigneurial system of land settlement.

Upper Canada, roughly the modern province of Ontario,

included most of the English-speaking population and

used English law and property systems. Both colonies had

weak elected assemblies. After the War of 1812 (1812–15),

hard times led English, Irish, and Scottish settlers to immi-

grate to British North America in record numbers. Fear-

ing loss of control of the government of Lower Canada,

some French Canadians revolted in 1837, which triggered

a rebellion in Upper Canada. Both rebellions were quickly

quashed, and the British government unified the two

Canadas into the single province of Canada (1841) (see

D

URHAM

R

EPORT

). This form of government did not

work well, however, as the main political parties had

almost equal representation in the legislature and thus had

trouble forming stable ministries.

From 1848, the rapidly growing provinces in British

North America won self-government and virtual control

over local affairs. By the 1860s, there was general agreement

on the need for a stronger central government, which led to

the confederation movement. In 1867, representatives of

Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia agreed

to petition the British government for a new federal gov-

ernment. The British North America Act (1867) provided

a parliamentary government for the new dominion, with

the British monarch remaining head of state and the British

government continuing to be responsible for foreign affairs

until 1931, when Canada gained complete independence.

In the east, P

RINCE

E

DWARD

I

SLAND

and N

EWFOUND

-

LAND

feared domination by the larger provinces but even-

tually joined the Dominion of Canada, in 1873 and in

1949, respectively. The new western provinces also joined:

Manitoba in 1870, British Columbia in 1871, Alberta in

1905, and Saskatchewan in 1905. The lightly populated

Northwest Territories and the Yukon Territory of the far

north became part of Canada in 1870 and 1898, respec-

tively. And finally, after 23 years of negotiation, in 1999 the

territory of Nunavut was carved from the Northwest Terri-

tories as a homeland for the native Inuit peoples.

For about 30 years following confederation, more peo-

ple left Canada than arrived as immigrants, most lured away

by economic prospects in the rapidly industrializing United

States. Sir John Macdonald, the prime minister for most of

the period (1867–73 and 1878—91), valued western devel-

opment as a means of strengthening the nation and actively

promoted policies designed to attract immigrants. The first

piece of immigrant legislation was the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1869, mainly aimed at safe travel and protection from

passenger abuse. With powers granted to the cabinet by the

act itself, orders-in-council could be used to amend the leg-

islation, thus avoiding passage of completely new measures.

Through such orders-in-council, classes of undesirable ele-

ments such as criminals, prostitutes, and the destitute were

specified in amendments, moving Canada toward an

increasingly restrictive immigration policy. In 1885, the gov-

ernment introduced a $50 head tax on Chinese immigrants,

effectively barring widespread immigration from China.

CANADA—IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW 45

Still, the Canadian government was interested in Euro-

pean laborers, especially if they were willing to farm the

western prairies. The federal government, which adminis-

tered western lands under the Department of Agriculture,

tried to encourage immigration with a generous homestead

provision. The most important single piece of legislation was

the D

OMINION

L

ANDS

A

CT

(1872), under which any male

head-of-family at least 21 years of age could obtain 160 acres

of public homestead land for a $10 registration fee and six

months’ residence during the first three years of the claim.

The policy was on the whole a failure. An average of fewer

than 3,000 homesteaders per year between 1874 and 1896

took advantage of the program. Lack of railway access and

isolation contributed to the slow rate of development. As the

government continually sought funding for the building of

the Canadian Pacific Railway, it also launched plans to sell

lands to colonization companies. The plan failed between

1874 and 1877 and again between 1881 and 1885. The

generous provision of sale of land to colonization companies

at $2 per acre, with the promise of a rebate once settlement

and transportation links to other settlements had been estab-

lished, led to little more than massive land speculation.

Although 26 companies had procured grants totaling nearly

3 million acres by 1883, only one company fulfilled its

agreement. More successful were group settlement plans that

set aside large tracts for specific immigrant groups such as

the Mennonites (see M

ENNONITE IMMIGRATION

), Scandi-

navians, Icelanders (see I

CELANDIC IMMIGRATION

), Jews

(see J

EWISH IMMIGRATION

), Hungarians (see H

UNGARIAN

IMMIGRATION

), and Doukhobors.

From the mid–1890s until World War I (1914–18; see

W

ORLD

W

AR

I

AND IMMIGRATION

), favorable government

policies, eastern industrialization, and the opening of the

western provinces to agriculture brought 300,000–400,000

immigrants each year, most from the British Isles and cen-

tral and southern Europe. This relatively open policy was

nevertheless opposed by virtually all francophone nationalists

in Quebec, who feared that the French minority was being

deliberately swamped with English speakers. The flood of

immigrants led to passage of the 1906 I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

,

which greatly expanded the categories of undesirable immi-

grants, enhanced the power of the government to make judg-

ments regarding deportation, and set the tone for the

generally arbitrary expulsion of undesirable immigrants that

characterized Canadian policy throughout much of the 20th

century. In the period between World War I and World War

II (1939–45; see W

ORLD

W

AR

II

AND IMMIGRATION

), eco-

nomic depression and international turmoil kept immigra-

tion low, averaging less than 20,000 per year. After the war,

immigration remained a significant demographic force in the

country, especially during times of international crisis. The

I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1952 nevertheless continued to invest

the minister of citizenship and immigration with almost

unlimited powers regarding immigration. As late as 1957, 95

percent of all immigrants to Canada were from Europe or the

United States. That changed rapidly in the 1960s, as Euro-

pean countries abandoned their colonial empires in Africa

and Asia and the Canadian public began to support a more

active policy toward refugee resettlement. A new series of

IMMIGRATION REGULATIONS

in 1967 introduced for the

first time the principle of nondiscrimination on the basis of

race or national origin, virtually ending the “white Canada”

policy that had prevailed until that time. The following year,

the Union Nationale government in Quebec established its

own Ministry of Immigration, which was recognized by the

federal government as a result of the Couture-Cullen Agree-

ment in 1978. As a result, Quebec gained effective control

of nonsponsored immigration into the province and the right

to establish its own criteria. While the goal of the federal gov-

ernment was increasingly multicultural in character, Quebec

46 CANADA—IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

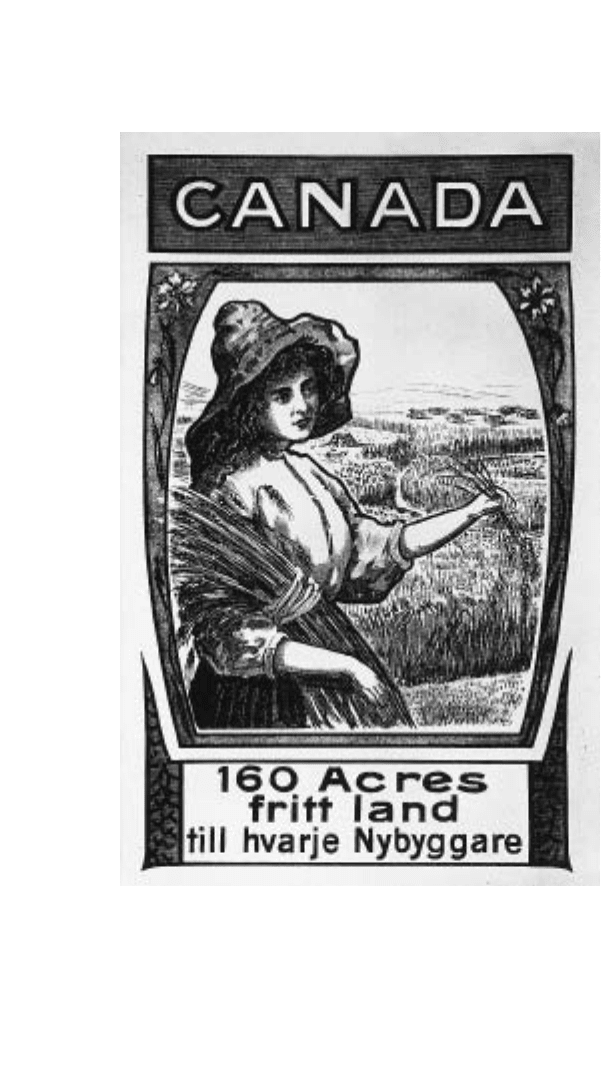

An advertisement in Swedish for Canadian land from the first

decade of the 20th century. Both Canada and the United

States advertised widely for agricultural immigrants to fill their

empty prairies.

(Canadian Department of the Interior/National

Archives of Canada/C-132141/TC-0754)

pursued what it called “cultural convergence,” receptive to

non-francophone cultures but clearly valuing maintenance of

francophone predominance.

Between 1965 and 2001, European immigration to

Canada dropped from 73 to 10 percent of the total.

Between 1852, when Statistics Canada began publishing

records, and 2001, about 16 million immigrants came to

Canada. Of these, almost 2 million came in the period

between 1991 and 2001, and almost two-thirds of these

were from Asia, mainly from China, India, Pakistan, Korea,

and the Philippines.

See also A

LIEN

L

AND

A

CT

;C

HINESE

I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

;I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

(1910); I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

(1976); I

MMIGRATION AND

R

EFUGEE

P

ROTECTION

A

CT

;

I

MMIGRATION

A

PPEAL

B

OARD

A

CT

; P.C. 695.

Further Reading

Badets, Jane, and Tina Chui. Canada’s Changing Immigrant Population.

Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 1994.

Beaujot, R

oderic. Population Change in Canada. Toronto: McClel-

land and Ste

wart, 1991.

Behiels, Michael D. Quebec and the Question of Immigration: From

Ethnocentrism to E

thnic Pluralism, 1900–1985. Ottawa: Cana-

dian Historical Association, 1991.

B

umsted, J. M. Canada’s Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook. Santa

Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, 2003.

Burnet, Jean R., with Har

old Palmer. “Coming Canadians”: An I

ntro-

duction to a History of Canada’s Peoples. Toronto: McClelland

and S

tewart, 1989.

Careless, J. M. S. Canada: A Story of Challenge. Cambridge: Cam-

bridge Univ

ersity Press, 1953.

Cowan, Helen I. British Emigration to British North America: The

First Hundred Years. Toronto: University of Tor

onto P

ress, 1961.

Dirks, Gerald E. Controversy and Complexity: Canadian Immigration

P

olicy during the 1980s. Montreal and Kingston: McGill–Queen’s

Univ

ersity Press, 1995.

Eccles, William J. France in America. New York: Harper & Row, 1972.

Friesen, Gerald. The C

anadian Pr

airies: A History. Toronto: Univer-

sity of Toronto Press, 1984.

Garcia y Griego, Manuel. “Canada: Flexibility and Control in Immi-

gration and Refugee Policy.” In Controlling Immigration: A

G

lobal P

erspective. Eds. Wayne A. Cornelius, P. L. Martin, and J.

F. H

ollifield. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994.

Granatstein, J. L., et al. Nation: Canada since Confederation. 3d ed.

Tor

onto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1990.

Hansen, Marcus Lee. The Mingling of the Canadian and American Peo-

ples. Vol. 1, Historical. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press;

Toronto: Ryerson Press; London: Humphr

ey M

ilford, Oxford

University Press; 1940.

Hawkins, Freda. Canada and Immigration: Public Policy and Public

Concern. Montreal: McG

ill–Q

ueen’s University Press, 1988.

Hoerder, Dirk. Creating Societies: Immigrant L

ives in Canada. Mon-

treal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1999.

Iacovetta, Franca. A Nation of Immigrants: Women, Workers and Com-

munities in C

anadian History, 1840s–1960s. Toronto: University

of

Toronto Press, 1998.

Johnson, Stanley. A History of Emigration from the United Kingdom to

N

orth America, 1763–1912. London: Routledge and Sons, 1913.

Kelley

, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

History of C

anadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

T

oronto Press, 1998.

Knowles, Valerie. Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and

Immigr

ation P

olicy, 1540–1997. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1997.

Laquian, A

prodicio, and Eleanor Laquian. Silent Debate: Asian Immi-

gration and R

acism in Canada. Vancouver: University of British

Columbia Pr

ess, 1997.

Macdonald, Norman. Canada: Immigration and Colonization,

1841–1903. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1966.

M

agocsi, Paul Robert, ed. Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples. Toronto:

Univ

ersity of Toronto Press, 1999.

Simmons, Alan B. “Latin American Migration to Canada: New Link-

ages in the Hemispheric Migration and Refugee Flow Systems.”

International Journal 48 (Spring 1993): 282–309.

T

r

oper, Harold. “Canada’s Immigration Policy since 1945.” Interna-

tional Jour

nal 48 (Spring 1993): 255–281.

Woodsworth, J

ames S. Strangers within Our Gates. Toronto: University

of

Toronto Press, 1972.

Canadian immigration to the United States

From the earliest period of European settlement in North

America in the 17th century, France and England both

found it difficult to attract settlers to the cold northern

colonies that eventually became Canada. As communities

and economic opportunities grew to the south, however,

Canadians, most of whom spoke English, found it relatively

easy to relocate to the United States. As a result, Canada has,

throughout much of its history, suffered a net loss of migra-

tion, despite the immigration of more than 16 million peo-

ple between 1852 and 2002. According to the 2000 U.S.

census, 647,376 Americans claimed Canadian descent,

though the number clearly underrepresents those whose

families once inhabited Canada. Between 1820 and 2002,

more than 4.5 million Canadians immigrated to the United

States, though many were born in European countries and

only temporarily resided in Canada before moving on to the

south.

The first major migration of Canadians to the lands of

the present-day United States was in 1755, when Britain

captured A

CADIA

from France during the ongoing colonial

conflict that developed into the S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

(1756–63). Over the next several years, most of the French-

speaking Acadians were scattered throughout Britain’s

southern colonies, with about 4,000 eventually settling

together in L

OUISIANA

, where they formed a distinctive

“Cajun” culture. Tensions between British North America

and the thirteen American colonies that eventually won

their independence in the American Revolution (1775–83)

were high between 1763 and 1815. Though common cul-

tural and economic interests fostered a gradual normaliza-

tion of relations between the two countries, immigration

CANADIAN IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES 47

remained small prior to the 1850s. There was still a consid-

erable amount of good farmland in Canada, and talk of fed-

eration promoted hope for economic development in the

future.

Records before the second decade of the 20th century

are unreliable, but it seems that Canadian immigration to

the United States rose steadily from the 1850s. Around

1860, more Canadians left the country than European and

U.S. immigrants arrived. As the United States rapidly indus-

trialized after the Civil War (1861–65), Canadians fre-

quently took advantage of the demand for labor, moving

across the international border much as if they were moving

internally. French Canadians in Quebec, dissatisfied with

the old siegneurial system, left en masse, usually for the tex-

tile mills of New England. Farmers dissatisfied with weather

and isolation in the prairie provinces frequently sought bet-

ter conditions to the south. In the 1880s alone, 390,000

immigrated to the United States. Between 1891 and 1931,

another 8 million followed. Three-quarters were born in

Europe, but as many as 2 million were Canadian born. By

1900, Canadian immigrants comprised 8 percent of Amer-

ica’s foreign-born population. Even with passage of the

restrictionist J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of 1924, Canadians were

exempt and continued to come in large numbers, with

almost 1 million immigrating in the 1920s. Generally,

French-speaking Canadians settled in New England, while

English speakers often moved to New York or California.

Canadian immigration declined during the depression

and World War II era but picked up significantly during

the 1950s and 1960s, as Canadians took advantage of job

opportunities in a booming U.S. economy. Following pas-

sage of the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965,

however, which established hemispheric quotas, numbers

declined dramatically. Between the early 1960s and the early

1980s, the Canadian share of immigrants to the United

States dropped from 12 percent to 2 percent. Still, between

1931 and 1990, about 1.4 million Canadians officially

entered the United States, though the actual figures were

much higher. Statistics prior to the United States census of

1910 and the Canadian census of 1911 are estimates, as

Canadian movements were treated as internal migration

rather than international immigration, and there were

almost no regulations before 1965.

Ratification of the N

ORTH

A

MERICAN

F

REE

T

RADE

A

GREEMENT

(NAFTA), reducing trade barriers between

Canada, the United States, and Mexico, further strength-

ened economic ties between Canada and the United States.

NAFTA stipulated that business managers and other pro-

fessionals should be allowed to move more freely across bor-

ders. Between 1991 and 2002, about 185,000 Canadians

came to the United States, with larger numbers than ever

coming as well-paid professionals.

See also C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY

OVERVIEW

;F

RENCH IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Brault, Gerard J. T

he French Canadian Heritage in New England.

Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England; Kingston:

McG

ill–Queen’s University Press, 1986.

Chiswick, Barry R., ed. Immigr

ation, Language, and Ethnicity: Canada

and the U

nited States. Washington, D.C.: AEI Press, 1992.

Ducharme, J

acques. The Shadows of the Trees: The Story of French-

Canadians in New E

ngland. New York: Harper and Row, 1943.

H

ansen, Marcus Lee, and John Bartlett Brebner. The Mingling of the

Canadian and A

merican Peoples. New Haven, Conn.: Yale Uni-

versity Pr

ess, 1940.

Lines, Kenneth. British and Canadian Immigration to the United States

since 1920. San Francisco: R. and E. Research Associates, 1978.

Long, J

ohn F., and Edward T. Pryor, et al. Migration between the

United S

tates and Canada. Washington, D.C.: Current Popula-

tion Reports/S

tatistics Canada, February 1990.

Marchand, S. A. Arcadian Exiles in the Golden Coast of Louisiana.

New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Library, 1943.

S

amuel, T. J. “Migration of Canadians to the U.S.A.: The Causes.”

International Migration 7 (1969): 106–116.

S

t. J

ohn-Jones, L. W. “The Exchange of Population between the

U.S.A. and Canada in the 1960s.” International Migration 11

(1973): 32–51.

T

r

uesdell, Leon E. The Canadian-Born in the United States,

1850–1930. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1943.

Vedder, R. K., and L. E. Gallaway. “Settlement Patterns of Canadian

Emigrants to the U.S., 1850–1960.” Canadian Journal of Eco-

nomics 3 (1970): 476–486.

Cape Verdean immigration

Although Cape Verdeans have never constituted a large

immigrant group in North America, they formed an impor-

tant cog in the 19th-century Atlantic whaling industry

before finally settling in New England. In the U.S. census of

2000, 77,203 Americans claimed Cape Verdean descent,

though the actual figure is much higher. Most settled in

Massachusetts and Rhode Island. According to the Cana-

dian census of 2001, there were only 320 Cape Verdeans in

Canada, though here too the figure is likely low. Most live in

Toronto or Montreal.

Cape Verde is group of Atlantic islands occupying

1,600 square miles off the west coast of Africa between

15 and 17 degrees north latitude. The nearest countries

are Mauritania and Senegal to the east. Cape Verde com-

prises 15 stark volcanic islands populated by an estimated

405,163 citizens. Portuguese settlers began to colonize the

islands in the 15th century and soon began to import

African slaves. Consequently, 70 percent of the people of

Cape Verde are Creole mulattos, while Africans comprise

the rest. Roman Catholicism is the principal religion.

Through a regular series of droughts, imposition of the

slave trade until 1878, and oppressive Portuguese labor

legislation well into the 20th century, many Cape

Verdeans chose to seek their fortunes at sea on American

48 CAPE VERDEAN IMMIGRATION

whaling ships, staying in New England to harvest cran-

berries. The earliest Cape Verdean settlers arrived during

the mid-19th century, but they did not come in signifi-

cant number until the early 20th century, when Cape

Verdean seaman were routinely carrying laborers from

their homeland to New Bedford, Massachusetts, and

Providence, Rhode Island.

Until the restrictive E

MERGENCY

Q

UOTA

A

CT

of 1921

and J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of 1924, Cape Verdeans arrived

freely as Portuguese subjects. Thereafter, almost none were

allowed in. During the 1920s and 1930s, many of those

already in the country moved to Ohio and Michigan to

work in the auto and steel industries. This situation

remained until 1975 when Cape Verde gained its indepen-

dence. Under provisions of the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965, their potential allotment of

visas immediately rose from 200 to 20,000.

The number of Cape Verdeans in both the United

States and Canada is significantly higher than official fig-

ures suggest for a number of reasons. Until 1975, most car-

ried Portuguese passports, reported themselves as

Portuguese, and often associated with Portuguese commu-

nities in North America. Immigration agents usually

grouped them with Portuguese immigrants, or in the

ambiguous “Other Atlantic Islands” category, making

exact counts difficult. In census questions, some claimed

African-American or African-Canadian status. With the

coming of independence, a newer generation asserted their

Cape Verdean identity and began to speak their native

Crioulo, a distinct creolized language based on Portuguese.

It has been estimated that between 43,000 and 85,000

Cape Verdeans immigrated to the United States between

1820 and 1976, based on a percentage of total Portuguese

immigrants.

In North America, Cape Verdeans, were both oppressed

as Africans and isolated within the black community as

Roman Catholics. As a result, they tended to maintain dis-

tinct communities dominated by extended families. Given

their grouping with European Portuguese immigrants prior

to 1975, it is impossible to say how many Americans are

descended from Cape Verdeans, but generally accepted esti-

mates place the figure at about 400,000. About 10,000

Cape Verdeans immigrated to the United States between

1992 and 2002. The total immigrant population in Canada

is a little more than 300, with about one-third coming dur-

ing the 1990s.

Further Reading

Busch, B. C. “Cape Verdeans in the American Whaling and Sealing

Industry

, 1850–1900.” American Neptune 25, no

. 2 (1985):

104–116.

Carr

eira, A. The People of the Cape Verde Islands: Exploitation and Emi-

gration. Trans. Christopher Fyfe. Hamden, Conn.: Archon

Books, 1982.

Halter, Marilyn. Between Race and Ethnicity: Cape Verdean American

I

mmigration, 1860–1965. Urbana: University of Illinois Press,

1993.

Hay

den, R. C. A

frican-Americans and Cape Verdean–Americans in New

B

edford: A History of Community and Achievement. Boston: Select

Publications, 1993.

L

obban, R. A. Cape

Verde: Crioulo Colony to Independent Nation. B

oul-

der, Colo.: Westview Press, 1995.

Machado, D. M. “Cape Verdean Americans.” In Hidden Minorities:

The P

ersistence of E

thnicity in American Life. Ed. J. H. Rollins.

W

ashington, D.C.: University Press of America, 1981.

Carpatho-Rusyn immigration See R

USSIAN

IMMIGRATION

.

Carolina colonies

The Carolina colony, later divided, was the gift of Charles

II (r. 1660–85) to eight loyal courtiers who had followed

him into exile during the English Civil War. Led by Sir John

Colleton, on March 24, 1663, the “true and absolute Lords

Proprietors of Carolina” were granted proprietary control of

all lands between the V

IRGINIA COLONY

and Florida. There,

they developed a plantation society, heavily dependent on

slavery, producing wood, naval stores, hides, rice, and

tobacco for the international market. By the mid-18th cen-

tury, slaves made up the majority of South Carolina’s popu-

lation. A policy of religious toleration led to a diverse

European population throughout the Carolinas, including

large numbers of Scots (15 percent of the European popu-

lation), Irish and Scots Irish (11 percent), Germans (5 per-

cent), and French Huguenots (3 percent).

The earliest attempt to settle in the Carolinas was the

ill-fated R

OANOKE COLONY

venture of 1584–90. Taking up

land bestowed by Queen Elizabeth, S

IR

W

ALTER

R

ALEIGH

carefully planned the first English colony in territory

claimed by Spain but far north of any area of actual settle-

ment. Located inside the Outer Banks, Roanoke was diffi-

cult to reach, requiring navigation of treacherous Cape

Hatteras. Relations with the native peoples were bad from

the beginning. When Sir Francis Drake visited the colony in

1586, the remaining settlers determined to return to En-

gland with him. A second attempt by Raleigh in 1587 fared

worse. Diplomatic tensions and war with Spain kept any

English ships from visiting Roanoke until 1590. By then,

the colony had been deserted, and the settlers either killed or

absorbed into the local population.

Hoping to grow rich through land sales and rents, the

Lords Proprietors of Carolina subdivided their grant into the

Albemarle region, bordering Virginia; the Cape Fear region,

along the central coast; and Port Royal, in present-day South

Carolina. With personal investment by Carolina proprietors

and the vigorous leadership of Anthony Ashley Cooper

CAROLINA COLONIES 49

(later the earl of Shaftesbury), they instituted the Funda-

mental Constitutions of Carolina, which provided for a local

aristocracy. Those purchasing large tracts of land received a

title and the right to a seat on the Council of Nobles.

Smaller landowners sat in an assembly with the right to

accept or reject council bills. Unsuited to the wilds of a new

territory where small farmers were needed to work the land,

the system attracted few settlers. As a result, the early econ-

omy of the colony was based on logging and a vigorous trade

with local tribes, especially in deerskins. Europeans intro-

duced firearms into an already volatile system of tribal con-

flict and encouraged the capture of Native Americans who

were then taken into slavery. By 1708, there were 1,400

Indian slaves, and 2,900 African slaves in the Carolinas.

Overpopulation in the British sugar island of Barbados

eventually led to the creation of a successful plantation econ-

omy along Carolina’s southern coast, most notably growing

indigo and rice for the cash market. Almost half the white

inhabitants of the Port Royal region had emigrated from

Barbados, many of them wealthy younger sons who brought

experience and slaves, as well as a political independence

that separated them from the early proprietors. As a result,

although the economy flourished, the government was in

disarray. By 1719, an increasingly representative form of

local government had asserted itself, and the last propri-

etary governor was overthrown. Ten years later, King George

I (r. 1714–27) established the royal colonies of North Car-

olina and South Carolina.

The revocation in 1685 of the Edict of Nantes, which

had granted a degree of religious tolerance to French Protes-

tants (Huguenots), led to the settlement of about 500

Huguenots in the Carolina colonies. After attempts to raise

silkworms and grapes failed, many settled in and around

Charleston, becoming merchants and businessmen. Most

did well economically and by 1750 were indistinguishable,

except for surnames, from their English counterparts. The

Scots-Irish often came as indentured servants (see

INDEN

-

TURED SERVITUDE

) and tended to settle in the backcountry

when their service was completed. The War of the Spanish

Succession (1701–14) and the severe winter of 1708–09

drove thousands of Germans to migrate, first to England as

refugees, then to the British colonies, including about 600

to the backcountry of the Carolinas. On the frontier, the

clannish Scots-Irish and Germans were joined from the

1740s by others who migrated from northern colonies down

the Great Philadelphia Road (also known as the Great

Wagon Road), which ran from Philadelphia to Camden,

South Carolina. It is estimated that by the time of the Amer-

ican Revolution (1775–83), the Scots-Irish may have com-

prised a majority of the 140,000 inhabitants of the Carolina

backcountry. The religious toleration of the Carolinas also

attracted a variety of migrant groups seeking religious free-

dom as well as land, including Baptists, Quakers, Presbyte-

rians, Moravians, and members of the Reformed Church.

Further Reading

Hofstadter, Richard. America at 1750: A Social Por

trait. New York:

Alfred A. Knopf, 1971.

Lefler, Hugh T., and William S. Powell. Colonial North Carolina: A

Histor

y

. New York: Scribner’s, 1973.

S

irmans, M. Eugene. Colonial South Carolina: A Political History,

1663–1763. Chapel Hill: Institute of Early American History

and C

ultur

e, University of North Carolina Press, 1966.

Unser, Daniel H., Jr. Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in a Frontier Exchange

E

conomy

. Chapel Hill: Institute of Early American History and

Culture, U

niversity of North Carolina Press, 1992.

Weir, Robert M. Colonial South Carolina: A History. Millwood, N.Y.:

KT

O, 1983.

W

ood, Peter H., et al., eds. Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial

Southeast. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989.

Carriage of Passengers Act (United States)

(1855)

The rapid influx of Irish, G

erman, and Chinese immigrants

into the United States after 1845 was accompanied by a

series of steamship disasters and the prevalence of cholera,

typhus, and smallpox among arriving immigrants. In late

1853, New York senator Hamilton Fish, a Republican,

called for a select committee to “consider the causes and the

extent of the sickness and mortality prevailing on board of

emigrant ships” and to determine what further legislation

might be necessary.

With the support of President Franklin Pierce,

Congress repealed the M

ANIFEST OF

I

MMIGRANTS

A

CT

(1819) and subsequent measures relating to transportation

of immigrants, replacing them on March 3, 1855, with “an

act to extend the provisions of all laws now in force relating

to the carriage of passengers in merchant-vessels, and the

regulation thereof.” Its main provisions included

1. Limitation of passengers, with no more than one

person per two tons of ship burden

2. Requirement of ample deck space—14–18 square

feet per passenger, depending on the height between

decks—and adequate berths

3. Requirement of ample foodstuffs, including the fol-

lowing per each passenger: 20 pounds of “good navy

bread,” 15 pounds of rice, 15 pounds of oatmeal,

10 pounds of wheat flour, 15 pounds of peas and

beans, 20 pounds of potatoes, one pint of vinegar,

60 gallons of fresh water, 10 pounds of salted pork,

and 10 pounds of salt beef (with substitutions

allowed where specific provisions could not be

secured “on reasonable terms”)

4. Requirement of the captain to maintain sanitary

conditions on board

5. Extension of all provisions to steamships, supersed-

ing the Steamship Act of August 13, 1852

50 CARRIAGE OF PASSENGERS ACT

With advances in shipbuilding technology greatly increasing

the size of ships, modifications in the space and food

requirements were made in a carriage of passengers act of

July 22, 1882.

Further Reading

Bromwell, William J. History of Immigration to the United States,

1819–1855. 1855. R

eprint, New York: Augustus M. Kelley,

1969.

Hutchinson, E. P

.

Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. P

hiladelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981.

Cartier, Jacques (1491–1557) explorer

The French king Francis I’s (r. 1515–47) search for a sea-

soned mariner to lead his country’s challenge to Spain and

Portugal in the recently discovered Americas brought to the

forefront Jacques Cartier. Although Cartier found neither

gold nor the Northwest Passage to Asia, his three voyages to

the Americas between 1534 and 1542 firmly established

French claims to Canada (see C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION

SURVEY AND POLICY REVIEW

).

Cartier was raised in the bustling seaport of Saint-

Malo in northern France, and had almost certainly traveled

to the Americas as a young man, perhaps in the company

of Giovanni da Verrazano. Cartier first sailed from Saint-

Malo with two ships and 61 men in April 1534. Explor-

ing the coasts of northern N

EWFOUNDLAND

, Anticosta

Island, and P

RINCE

E

DWARD

I

SLAND

, he claimed the

region for France and returned to a hero’s welcome. Freshly

outfitted with three ships, in May 1535, he returned to the

New World to explore the St. Lawrence River, certain that

he had found the fabled western passage through the con-

tinent. Native tales of the fabulous wealth of “Saguenay”

led him further inland, where he established French claims

to the areas surrounding the future cities of Quebec and

M

ONTREAL

, in present-day Q

UEBEC

province. With the

kidnapped Huron chief Donnaconna personally conveying

details of the mysterious land of Saguenay to Francis I, in

1541, the French king outfitted Cartier for a third journey,

with five ships and 1,000 men. The settlement of Charles-

bourg Royal was founded in 1542, but native opposition

and infighting between Cartier and Jean-François de La

Rocque de Roberval, a late royal appointment as Cartier’s

nominal superior, led to abandonment of the settlement in

1543. Although Francis I was disappointed to find no

wealth in N

EW

F

RANCE

, Cartier’s explorations led to fur-

ther development 50 years later.

Further Reading

Blashfield, Jean F. Cartier: Jacques Cartier’s Search for the Northwest Pas-

sage. Minneapolis, Minn.: Compass Point Books, 2002.

Car

tier

, Jacques. The Voyages of Jacques Cartier. Introduction by Ram-

say Cook. T

oronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993.

Trudel, Marcel. The Beginnings of New France, 1524–1663. Toronto:

M

cClelland and Stewart, 1972.

Vachon, André. Dreams of Empire: Canada before 1700. Ottawa: Pub-

lic Ar

chiv

es of Canada, 1982.

Castle Garden

Castle Garden was the first formal immigrant depot of the

United States, operating from 1855 until 1892 at the

southern tip of New York’s Manhattan Island. Built as a

fort prior to the War of 1812, it soon became an enter-

tainment center, most famous for hosting the Swedish

singer Jenny Lind in 1850. In 1855, the New York State

Board of Commissioners of Immigration converted it into

a processing station for immigrants arriving at the city (see

N

EW

Y

ORK

,N

EW

Y

ORK

).

Prior to 1855, immigrants arrived haphazardly at a vari-

ety of New York City docks. The chaotic scenes there, as

bags were sorted and directions given in many languages,

reflected the disorganized state of immigration policy. Only

in 1847 was a state board of immigration established, hos-

pitals and temporary quarters established on the city’s Ward’s

Island, and an employment office established on Canal

Street. Still, in 1849, the courts judged immigrants to be a

type of “foreign commerce” and hence left their care to the

Treasury Department. With neither a federal immigration

bureaucracy nor an official national policy, local port offi-

cials kept few records, and those they did keep were often

inaccurate. As hundreds of thousands of immigrants, largely

from Ireland and Germany, poured into New York City

every year after the mid-1840s, the state commissioners real-

ized that a better system was needed for tracking immigrant

entry, guarding against disease, and protecting newly arrived

immigrants from exploitation.

After 1855, immigrants were ferried from their ships to

Castle Garden, where immigration officers counted them

and obtained information regarding age, religion, occupa-

tion, and value of personal property. Immigrants were

required to bathe with soap and water. And though few ever

received direct financial assistance, they were able to

exchange money, purchase food at reasonable rates (kitchen

facilities were provided), buy railroad tickets, and receive job

advice, all relatively free from the influence of predatory

“providers.” There was no formal housing there, but immi-

grants were provided with temporary shelter. During the

Civil War (1861—65), Union recruiting officers met arrivals

at Castle Garden, offering large bonuses and other incen-

tives for joining the army.

As the volume of immigration increased dramatically

in the 1870s, states receiving large numbers of immigrants

petitioned the federal government for revision of immigra-

tion policies. State and local authorities had earlier levied

a head tax on immigrants to provide services, but this had

been declared unconstitutional in the Passenger Cases of

CASTLE GARDEN 51

1849. An alternate system was devised putting more of

the burden on transporters, allowing shipmasters to either

post bonds or pay commutation fees for healthy passen-

gers. This, too, the courts declared unconstitutional, in

1876, on the grounds it interfered with “foreign com-

merce,” an area reserved to congressional oversight. After

years of appeals, New York State officials threatened to

close Castle Garden unless the federal government agreed

to fund its operations. As a result, in 1882 a head tax of

50¢ was assessed on every immigrant in order to meet the

initial costs of reception. New federal guidelines in 1890

requiring more extensive physical and mental examina-

tions, along with the massive influx of immigrants—

almost 5 million coming through New York alone during

the 1880s—led the federal government to establish a new

immigrant depot at E

LLIS

I

SLAND

.

Further Reading

Andrews, William Loring. The Iconography of the Battery and Castle

Gar

den. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901.

Hall, A. O

akey. When Jenny Lind Sang in Castle Garden. New York:

Ladies’ H

ome Journal, 1896.

Novatny, Ann. Strangers at the Door: Ellis Island, Castle Garden, and the

G

reat Migration to America. Riverside, Conn.: Chatham Press,

1972.

S

v

ejda, George J. Castle Garden as an Immigrant Depot. Washington,

D.C.: Division of History, Office of Archaeology and Historic

P

reservation, 1968.

census and immigration

The United States and Canada each conduct a national cen-

sus every 10 years for the purpose of gaining reliable statis-

tics on their evolving populations. These statistics are used

to produce a variety of official population studies and are

made available to government agencies, scholars, businesses,

health care officials, and others interested in better under-

standing population composition in order to provide gov-

ernmental, social, or commercial services. The statistics are

particularly relevant to the formulation of government

immigration policies and to the development of social ser-

vices for immigrants, who are likely to be in greater need of

those services than the general population is. The most

recent census taken in the United States was in March 2000,

52 CENSUS AND IMMIGRATION

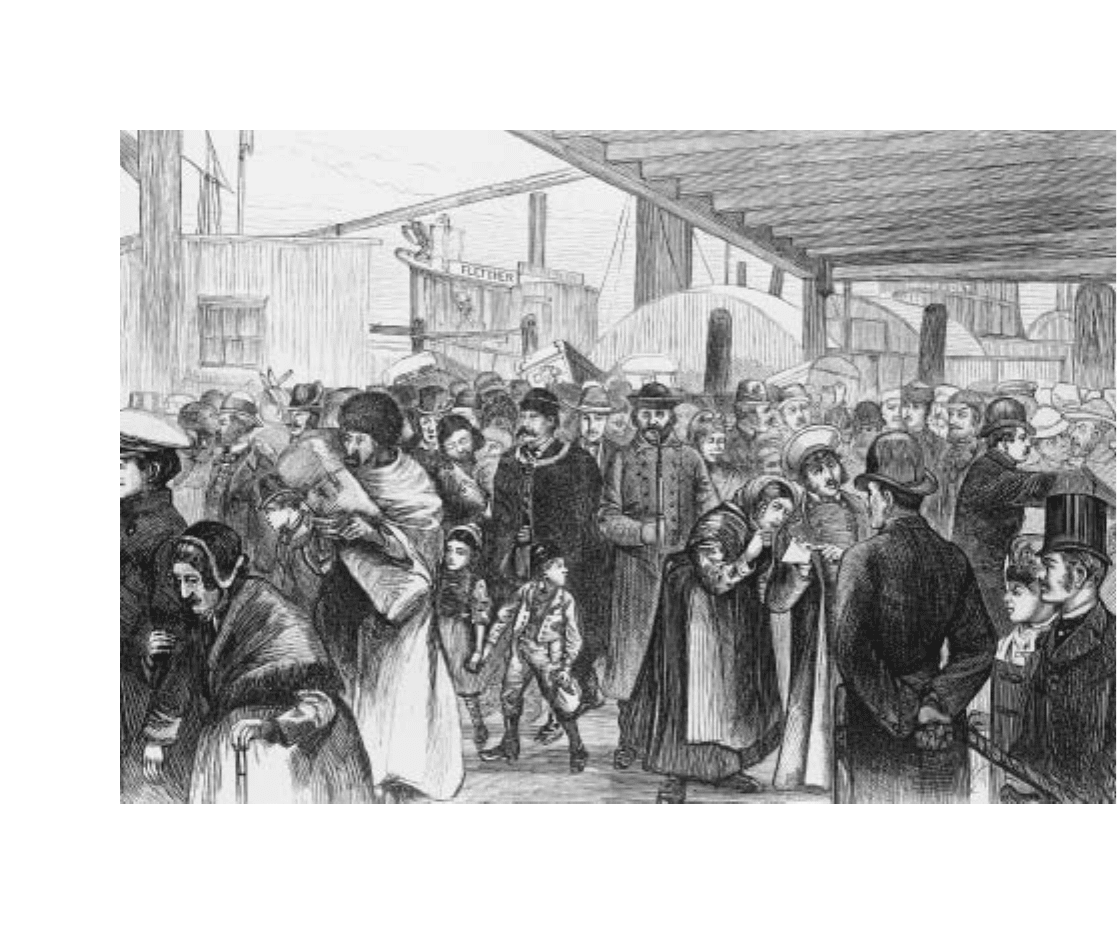

An illustration from Harper’s Weekly, May 29, 1880, depicts immigrants landing at Castle Garden, New York City. From 1855, Castle

Garden served as the main immigration depot for the United States until Ellis Island was opened in 1892.

(Library of Congress, Prints

& Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-99403])

and in Canada, in May 2001. In both countries, it is illegal

for anyone associated with census taking to reveal informa-

tion about individuals.

U.S. Census

The first U.S. national census was taken in 1790, as mandated

by Article 1, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, for the pur-

pose of apportioning representation to the various states. As

the country grew and became more complex, new categories

were added to the census. In 1850, questions were first

included on a wide array of social issues, including “place of

birth.” In 1850, the foreign-born population was 9.7 per-

cent. During peak years of immigration (1860–1920), it fluc-

tuated between 13 and 15 percent of the population. In 1970,

due to restrictive policies, the foreign-born population

reached an all-time low at 4.7 percent. The unexpected and

rapid increase in the

NEW IMMIGRATION

from Asia and Latin

America since 1970 steadily drove the percentage higher. In

2000, the 28.4 million foreign-born Americans represented

10.4 percent of the total population. Data on Americans born

outside the United States are generally comparable between

1850 and 2000, though there are certain inherent weaknesses

and refinements that must be taken into account. For

instance, in 1890, children born in foreign countries who had

an American citizen as a parent began to be counted as

“native” rather than “foreign born.” Also, evolving political

boundaries, particularly in Europe, have made it difficult to

know the exact ethnicity of many immigrants, or the modern

country to which one might assign one’s ancestry.

Canadian Census

The first Canadian national census, provided for under Sec-

tion 8 of the Constitution Act (British North America Act)

of 1867, was taken in 1871, primarily to apportion parlia-

mentary representation. From the first census, ancestral ori-

gins were recorded. In 1881, British Columbia, Manitoba,

and Prince Edward Island were added to the four original

provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, and

Ontario. New questions relating to religion, birthplace, cit-

izenship, and period of immigration were added in 1901.

The census was initially the responsibility of the Ministry

of Agriculture and then the Ministry of Trade and Com-

merce (1912) before the Dominion Bureau of Statistics was

created in 1918. In order to mark economic development,

the Bureau of Statistics introduced a simplified quinquen-

nial (every five years) census in 1956. In 1971, respondents

were asked to complete their own census questionnaire for

the first time, and the Dominion Bureau of Statistics was

renamed Statistics Canada.

See also

RACIAL AND ETHNIC CATEGORIES

.

Further Reading

Anderson, Margo J. The American Census: A Social History. New

Hav

en, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1988.

———, ed. Encyclopedia of the U.S. Census. Washington, D.C.: Con-

gressional Q

uarterly Press, 2000.

Bryant, Barbara Everett, and William Dunn. Moving Power and

Money:

The P

olitics of Census Taking. Ithaca, N.Y.: New Strategic

P

ublications, 1995.

Edmonston, Barry, and Charles Schultze, eds. Modernizing the U.S.

Census. Washington, D.C.: N

ational A

cademy Press, 1995.

“History of the Census of Canada.” Statistics Canada. Available

online. URL: http://www.statcan.ca/english/census96/history.

htm. Modified July 5, 2001.

Kent, Mary M., et al. “First Glimpses from the 2000 U.S. Census.”

Population Bulletin 56, no. 2 (June 2001).

R

obey

, Bryant. “Two Hundred Years and Counting: The 1990 Cen-

sus.” Population Bulletin 44, no. 1 (1989).

R

odrigue

z, Clara E. Changing Race: Latinos, the Census, and the His-

tory of E

thnicity in the United States. New York: New York Uni-

versity P

ress, 2000.

Skerry, Peter. Counting on the Census? Race, Group Identity, and the

E

v

asion of Politics. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution,

2000.

U.S. Census B

ur

eau. Available online. URL: http://www.census.gov.

U.S. Office of Management and Budget. “Revisions to the Standards

for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity.”

Federal Register 62, no. 210 (October 30, 1997): 58,782–58,790.

Champlain, Samuel de (ca. 1567–1635) explorer,

businessman

Samuel de Champlain was the principal founder of N

EW

F

RANCE

and the first European explorer of much of modern

Quebec and Ontario.

Champlain was born in the Atlantic French seaport of

Brouage. Little is known of his early life, but he became a

devout Roman Catholic as French Catholics and

Huguenots battled for his hometown. Champlain’s skill as

a cartographer, artist, and author of his first journey to the

Americas with a Spanish expedition in 1599 led to his com-

mission by Henry IV, king of France (r. 1589–1610) to

establish a French colony in North America. Although

J

ACQUES

C

ARTIER

had claimed A

CADIA

and the St.

Lawrence Seaway in the 1530s, the bitter winters had

restricted French interest to fishing along coastal waters.

Champlain founded ill-fated colonies at St. Croix Island

(1604) and Port Royal, N

OVA

S

COTIA

(1606), before estab-

lishing the first permanent French settlement in North

America at Quebec (1608), where only eight of the origi-

nal 24 Frenchmen survived the first winter. In 1627, he

became head of the C

OMPAGNIE DE LA

N

OUVELLE

F

RANCE

, often known as the Company of One Hundred

Associates, which was granted title to all French lands and a

monopoly on all economic activity except fishing, in return

for settling 4,000 French Catholics in Canada. Although

the fur trade flourished, Frenchmen paid little attention to

Champlain’s calls to establish farming settlements. At the

time of his death in 1635, the population of Quebec was

CHAMPLAIN, SAMUEL DE 53