Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

only about 200. His own wife had returned to France after

four years, disliking the hardship and isolation. For more

than a quarter of a century, Champlain worked strenuously

to hold Canada against British incursions, to maintain close

relations with the Algonquians and Hurons, and to con-

vert the Native Americans to Christianity.

Further Reading

Bishop, Martin. Champlain: The Life of Fortitude. 1948. Reprint, New

Yor

k: Octagon Books, 1979.

Heidenreich, C. E. Explorations and Mapping of Samuel de Champlain,

1603–1632. Toronto: B. V. Gutsell, 1976.

M

orison, Samuel Eliot. Samuel de Champlain: Father of New France.

Boston: Little, Brown, 1972.

P

ar

kman, Francis. France and England in North America. Vol. 1. New

Yor

k: Library of America, 1983.

Trudel, Marcel. The Beginnings of New France, 1524–1663. Toronto:

M

cClelland and S

tewart, 1972.

Vachon, André. Dreams of Empire: Canada before 1700. Ottawa: Pub-

lic Ar

chiv

es of Canada, 1982.

Chavez, Cesar (1927–1993) labor organizer

Cesar Chavez became the most visible public spokesman

for the rights of migrant farmworkers in the United States

during the 1960s and 1970s and the first national symbol of

the Mexican-American labor community. His work as a

labor organizer led him to oppose consistently the agribusi-

ness industry’s use of both legal and illegal labor from Mex-

ico and thus brought him into conflict with other Hispanic

leaders who criticized his lack of commitment to La Raza

(the people).

Chavez’s father migrated with his family to Yuma, Ari-

zona, from Chihuahua, Mexico, in 1888. With the depres-

sion came loss of the family store in 1934 and the family

homestead in 1939, leading Chavez and the other members

of his family to become permanent migrant laborers. Living

in the San Jose barrio of Sal Si Puedes after two years in the

U.S. Navy (1944–46), Chavez became interested in com-

munity work and the political philosophies of nonviolence.

He worked with the Community Service Organization

(CSO) throughout the 1950s, rising to the position of exec-

utive director (1958–62). In 1958, Chavez became directly

involved in labor organization, leading a campaign in

Oxnard, California, to oust braceros (Mexican laborers) who

had been brought in to drive down labor wages (see

B

RACERO

P

ROGRAM

). The campaign was initially success-

ful, but Chavez realized that results would not be permanent

without a labor union to see that agreements were kept. In

1962, he established the Farm Workers Association (FWA)

but chose to maintain its independence from the A

MERICAN

F

EDERATION OF

L

ABOR

–C

ONGRESS OF

I

NDUSTRIAL

O

RGANIZATIONS

(AFL-CIO) and its branch the Agricul-

tural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), hoping to

maintain the strong sense of community activism that had

been part of the CSO.

Chavez emerged as a national figure in 1965 when he

led the FWA into a Delano, California, grape workers’ strike

that had been initiated by AWOC’s local director Larry Iti-

long on behalf of Filipino-American workers protesting the

hiring of low-wage braceros. The Delano strike captured

the attention of reformers of all classes and races, and many

from around the United States volunteered to help. In 1966,

Chavez led a much-publicized march from Delano to Sacra-

mento in order to present the matter to Governor Pat Brown

and continued to expand consumer boycotts. With an

emphasis on nonviolence, community solidarity, and reli-

gious fervor, Chavez’s work resembled to many Americans

the efforts of Martin Luther King, Jr., on behalf of African

Americans. Later that year, under Chavez’s suggestion, the

FWA took the name National Farm Workers Union (later

changed to United Farm Workers of America [UFW]) and

joined with AWOC in order to give farmworkers greater

bargaining power. In July 1970, the grape strike finally

54 CHAVEZ, CESAR

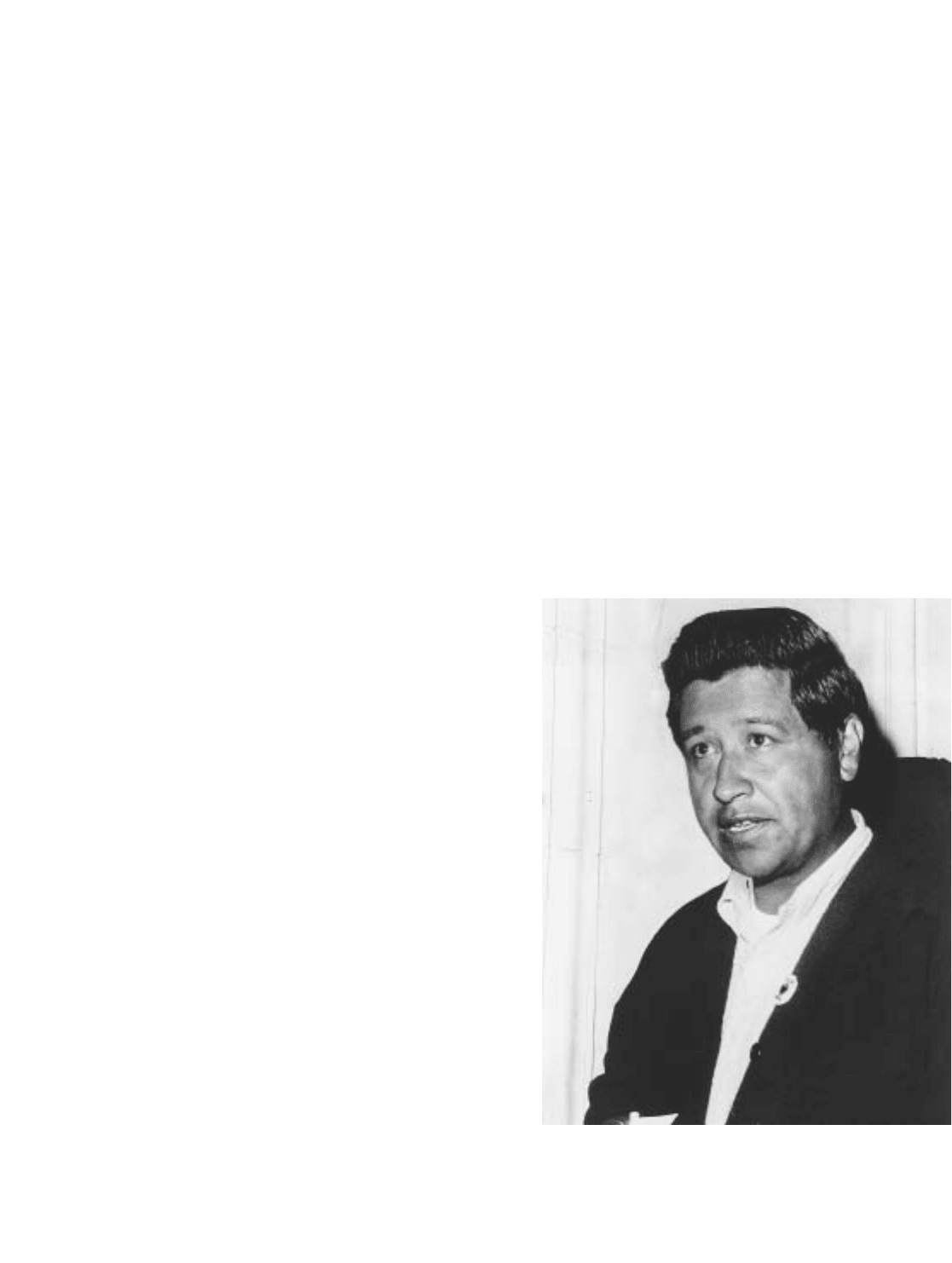

Cesar Chavez, photographed in 1966, was the first major

organizer of legal Mexican and Mexican-American migrant

farm laborers. His United Farm Workers of America waged a

long and bitter but ultimately successful strike against grape

growers in California (1966–70).

(Library of Congress, Prints &

Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-111017])

ended, with workers earning substantial increases in pay and

the union organization strengthened.

Although the Delano grape strike was his most visible

piece of labor activism, Chavez continued to organize strikes

and to speak out against illegal immigration and its detri-

mental effect on wages. As the 1970s progressed, he was

increasingly attacked by members of the Hispanic commu-

nity who argued that his commitment to working-class

issues worked against the greater good of Hispanics gener-

ally, including illegal Mexican immigrants who hoped to

better their lives by coming to the United States. He never-

theless continued to work with the governments of both

the United States and Mexico in order to secure protections

for the interests of legal Mexican Americans in the United

States. Chavez encouraged the U.S. government to include

provisions in the I

MMIGRATION

R

EFORM AND

C

ONTROL

A

CT

(1986) applying sanctions against employers who

knowingly hired illegal immigrants. In 1990, he signed an

agreement with the Mexican government stipulating that

Mexican citizens who were members of the UFW could also

qualify for Mexican social security benefits.

Further Reading

Etulain, Richard W., ed. Cesar Chavez: A Brief Biography with Docu-

ments. New York: Palgrave, 2002.

F

erris, S

usan, and Ricardo Sandoval. The Fight in the Fields: Cesar

Chavez and the F

armworkers Movement. New York: Harcourt

Brace J

ovanovich, 1997.

Griswold del Castillo, Richard, and Richard A. Garcia. Cesar Chavez:

A T

riumph of S

pirit. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press,

1995.

Levy

, J

acques E. Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa. New York:

W.

W. Norton, 1975.

Chicago, Illinois

For most of the 19th and 20th centuries, the city of Chicago

was one of the most desirable destinations for immigrants.

Emerging in the late 19th century as the hub of midwestern

development, Chicago had good rail access from eastern

ports of entry, and its slaughterhouses and industries pro-

vided jobs for unskilled workers. Large numbers of Ger-

mans, Irish, Swedes, Norwegians, Canadians, Czechs, Poles,

Greeks, and Italians clustered there in the 19th and early

20th centuries. After World War II (1939–45), Bosnian

Muslims, Latvians, Lithuanians, Pakistanis, Mexicans, and

Hasidic Jews created significant enclaves in Chicago.

According to the 2000 U.S. census, Chicago had the third

largest Hispanic population in the United States (753,644,

behind New York City and Los Angeles) and the seventh

largest Asian population (125,974). Its foreign-born popu-

lation was about 1.1 million.

Chicago began as a small military outpost established in

1816. By 1833, it was incorporated as a village with a pop-

ulation of more than 150. When the government forced a

land settlement on the local Indian tribes, removing them

west of the Mississippi River, the European population

boomed. By 1848, a canal was completed linking Chicago

to the Mississippi, and by 1856, it was the hub of 10 rail-

roads. The city continued to grow during and after the Civil

War (1861–65), becoming the leading grain, livestock, and

lumber market in the world. In 1870, Chicago’s population

of almost 300,000 was 17 percent German (52,316) and

13 percent Irish (40,000), with the percentage of foreign

born rapidly rising. Unprepared for the rapid influx of

inhabitants, the city was host to overcrowding, disease, and

degraded living conditions.

In response to the plight of the immigrants, in 1889,

J

ANE

A

DDAMS

opened the Hull-House settlement to pro-

vide assistance to the urban poor. The large pool of unskilled

labor fueled the city’s economic development but also led to

tensions. In May 1886, the deadly Haymarket bombing

during a labor rally revived nativist fears of immigrant radi-

calism. By 1890, Chicago was second only to New York in

population and a magnet for numerous immigrant groups.

In 1900, Swedes comprised almost 9 percent of Chicago’s

population (150,000), making it second only to Stockholm

in Swedish population. By 1920, it was the largest Norwe-

gian city in the world besides Oslo, and there was already a

Polish population of 400,000. Between 1910 and 1920, at

the peak of early 20th-century immigration, about three-

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 55

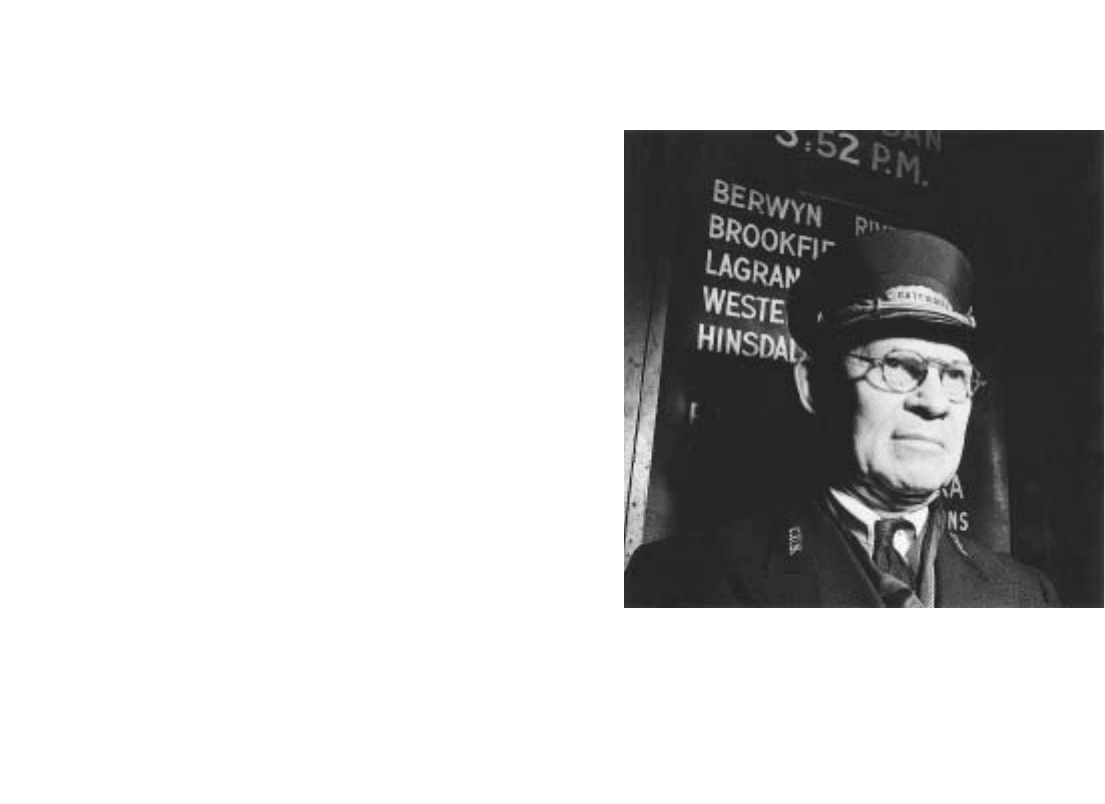

Charles Sawer, gateman at Union Station, Chicago, Illinois,

1943. In multiethnic Chicago, a man like Sawer was useful in

the train station, where he served as an interpreter in Yiddish,

Polish, German, Russian, Slovak, and Spanish.

(Photo by Jack

Delano/Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USW3-

015557-E])

fourths of Chicago’s population was either first- or second-

generation immigrant.

After World War I (1914–18), most of the immigrant

groups, including Czechs, Italians, Poles, and Greeks, began

to disperse into new neighborhoods and eventually the sub-

urbs, replaced by African Americans and other southerners

moving north for industrial work. A Mexican community

was well established by 1920, having moved north to work

in steel mills and meatpacking plants. By the 1920s, the

children and grandchildren of the “new immigrants” were

developing a strong middle-class base (see

NEW IMMIGRA

-

TION

). Together with economic ascendancy came greater

opportunities for leadership and financial backing, both

necessary to begin to influence the political process. A mile-

stone was reached in 1930 when Anton J. Cermak, born in

a mining town northwest of Prague, was elected mayor of

Chicago. From that point forward, most of the old Euro-

pean immigrant groups rapidly assimilated into the main-

stream of Chicago social and political life. Still, Chicago

was a city of immigrants. In 1927, almost 30 percent of its

population was born in Europe. The Jewish population

alone, composed largely of poor eastern Europeans, was

275,000.

After World War II (1939–45), Chicago continued to

attract immigrants. Historically a city populated mainly by

Europeans and African Americans, it became one of the

most ethnically diverse cities in the world. Mexicans con-

tinued to join the “colony” established after 1910, settling

mainly in South Chicago. Apart from the largely assimi-

lated Germans and Irish, Mexican Americans formed the

largest ethnic group in Chicago by far, with a population

of 1,132,147 in 2001 (in the greater Chicago-Gary-

Kenosha area). Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians

fleeing in the aftermath of the Vietnam War (1964–75)

and the Khmer repression came in large numbers during

the late 1970s and early 1980s, congregating in the North

Side neighborhood of Uptown. By 2000, there were about

25,000 Southeast Asians living in Chicago. Asian Indians

were one of the most rapidly growing populations, set-

tling mainly in western and northwestern suburbs. Indian

Americans benefited greatly from provisions of the I

MMI

-

GRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965, abolishing

racial quotas and favoring skilled workers such as engineers

and medical professionals. The act also gave preference to

family reunification, which enabled Indians to bring their

families to Chicago. Between 1980 and 2000, their num-

bers grew from about 32,000 to 123,000. There were also

large populations of Puerto Ricans (161,655) and Chinese

(78,277). In 1990–91, more than 5,000 Soviet Jews were

relocated in Chicago, representing more than 9 percent of

all Jewish émigrés to the United States. During the 1990s,

Chicago was still the fourth most popular destination for

immigrants, ranking behind New York City, Los Angeles,

and Miami, Florida.

Further Reading

Allswang, John M. A House for All Peoples: Ethic Politics in Chicago

1890–1936. Lexington: U

niversity Press of Kentucky, 1971.

Anderson, Philip J., and D

ag Blanck. Swedish-American Life in

Chicago: Cultur

al and Urban Aspects of an Immigrant People,

1850–1930. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University, 1991.

B

eijbom, U

lf. Swedes in Chicago: A Demographic and Social Study of the

1846–1880 Immigr

ation. Vaxjo, Sweden: Emigrants’ House,

1971.

Cohen, Lizabeth. M

aking a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago,

1919–1939. Ne

w York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Cutler, Irving. The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb. Champaign:

Univ

ersity of Illinois Press, 1996.

Erdmans, Mary Patrice. Opposite Poles: Immigrants and Ethnics in Pol-

ish Chicago

, 1976–1990. U

niversity Park: Pennsylvania State

University P

ress, 1998.

Jones, Peter D’A., and Melvin C. Holli. Ethnic Chicago. Grand Rapids,

M

ich.: E

rdmans, 1981.

Kantowicz, Edward R. Polish-American Politics in Chicago,

1888–1940. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975.

K

eil, Hartmut, and John B. Jentz, eds. German Workers in Industrial

Chicago, 1850–1910: A Compar

ative Perspective. DeKalb: North-

ern Illinois U

niversity Press, 1983.

Kopan, A. T. The Greeks in Chicago. Urbana: University of Illinois

P

r

ess, 1989.

Kourvetaris, G. A. First- and Second-Generation Greeks in Chicago.

Athens: National Center for Social Research, 1971.

Lo

voll, Odd S. A Century of Urban Life: The Norwegians in Chicago

befor

e 1930. Urbana, Ill.: Norwegian American Historical Soci-

ety, 1988.

McCaffr

ey, L. J. The Irish in Chicago. Urbana: University of Illinois

Press, 1987.

N

elli, H

umberto S. Italians in Chicago, 1880–1930. New York:

Oxford University Press, 1975.

Pacyga, Dominic A. Polish Immigrants and Industrial Chicago:

Workers

on the South Side, 1880–1922. Columbus: Ohio State Univer-

sity Pr

ess, 1991.

Parot, Joseph J. Polish Catholics in Chicago, 1850–1920. DeKalb:

N

or

thern Illinois University Press, 1981.

Philpott, Thomas L. The Slum and the Ghetto: Neighborhood Deterio-

ration and Middle-Class Reform, Chicago

, 1880–1930. N

ew York:

Oxfor

d University Press, 1978.

Rassogianis, Alex. “The Growth of Greek Business in Chicago:

1900–1930.” M.A. thesis, University of Wisconsin at Milwau-

kee, 1982.

Chicano

The term Chicano is a politicocultural indicator of one’s

identification as a pure-blood or mestizo (mixed race)

descendant of the native peoples of the old Aztec homeland

of Aztlán. Its origins are unclear, but it was first widely used

by young people in the U.S. Southwest during the 1950s. As

frustration set in over the lack of economic and social

progress during the 1960s, many Mexican-American leaders

throughout the southwestern states adopted the term as an

56 CHICANO

affirmation of their Indian past and a rejection of European-

American values. Going beyond the traditional political tac-

tics of earlier Mexican-American organizations, Chicano

leaders encouraged greater militancy in their activism. J

OSE

A

NGEL

G

UTIERREZ

established the Mexican American Youth

Organization in Texas, organizing a series of consciousness-

raising high school “walkouts” to protest Anglocentric text-

books and educational discrimination. In Denver, Colorado,

(Rodolfo) C

ORKY

G

ONZALES

left the Democratic Party in

1965 to form a Chicano-rights organization, the Crusade for

Justice. He was also instrumental in defining the Chicano

movement by helping draft the manifesto El Plan Espiritual

de Aztlán (1969) and writing its most enduring piece of liter-

ature, the epic poem I A

m Joaquín. Both men w

ere prominent

in establishing the national L

A

R

AZA

U

NIDA PARTY

(LRUP),

the political arm of the Chicano movement, which was most

prominent in the mid-1970s. During the 1970s, the Chi-

cano movement was closely associated with C

ESAR

C

HAVEZ

’s

struggle to improve conditions for migrant farmworkers, the

vast majority of whom were Mexicans. By the late 1970s, Chi-

cano activism began to subside and with it, the political preva-

lence of the term.

See also M

EXICAN IMMIGRATION

;T

IJERINA

,R

EIES

L

ÓPEZ

.

Further Reading

Acuña, Rodolfo. Occupied America: The Chicano Struggle for Libera-

tion. 3d ed. New York: Harper and Row, 1988.

Góme

z Q

uiñones, Juan. Chicano Politics: Reality and Promise,

1940–1990. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press,

1990.

G

onzale

z, Gilbert G., and Raul Fernandez. “Chicano History: Tran-

scending Cultural Models.” Pacific Historical Review 63 (Novem-

ber 1994): 469.

Chilean immigration

The earliest migration of Chileans to the north came dur-

ing the California gold rush of 1848–49, when some 7,000

immigrated to the United States, with most settling in San

Francisco and Santa Clara Counties. In 2000, 68,849 per-

sons of Chilean origin resided in the United States, with the

highest concentrations in Los Angeles; Miami, Florida; and

New York City. According to the Canadian census of 2001,

34,115 Canadians claimed Chilean descent, most residing

in Toronto and Montreal. Because the earliest “Chilenos”

frequently intermarried, the modern Chilean American is

more likely to be part of a general community than of an

ethnic enclave.

Chile is a long, narrow country of 288,800 square miles

along the west coast of South America between 17 and 55

degrees south latitude. With a coastline of 2,600 miles, it has

a long seafaring tradition that has invited immigration from

many countries, including Spain, Italy, Germany, Ireland,

Greece, Yugoslavia, and Lebanon. Peru forms its border to

the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east,

and the Pacific Ocean to the west. The Andes Mountains,

some of the highest in the world, stretch north to south

along its eastern border against the Atacama Desert in the

north, plains in the central region, and forests in the south.

An archipelago makes up much of southern Chile includ-

ing the largest island, Tierra del Fuego, which is shared with

Argentina. In 2002, the population was estimated at

15,328,467, with more than 5 million in the urban area of

the capital city of Santiago. About two-thirds of the popu-

lation is of mixed European and Indian descent (mestizo),

and almost all the others of European descent. Roman

Catholicism is the dominant religion, claimed by 89 percent

of the population. The other 11 percent are Protestant

Christians.

The Inca Empire ruled over Chile until the 16th-cen-

tury Spanish conquest. Chile fought for its independence

between 1810 and 1818, after which it established a signif-

icant economic relationship with the United States. Chilean

men often served on American whaling ships and sometimes

settled in northeastern U.S. ports. More than 7,000 entered

California during the gold rush of 1848–49, many of whom

were experienced miners. Nevertheless, throughout the 19th

and early 20th centuries there was only sporadic emigration.

Chile’s civil war of 1891 led thousands to immigrate to the

United States, Europe, and Argentina. After 1938, when a

leftist government was elected, conservative Chileans began

migrating to the United States, steadily increasing the

Chilean populations in New York City and Los Angeles.

Middle- and upper-class Chileans frequently came to the

United States for education. The election of marxist Sal-

vador Allende in 1970 led to an even larger exodus. Allende

was assassinated in 1973 by a repressive, U.S.-backed mili-

tary junta under General Augusto Pinochet, thus creating a

new wave of emigration of leftists who had supported

Allende. Both the United States and Canada were reluctant

to admit avowed marxists, fearing political complications

domestically and the appearance of undermining their anti-

communist allies in Chile. Continued pressure from church,

humanitarian, labor, and Hispanic groups nevertheless led

to minor refugee modifications. During 1973 and 1974,

Canada admitted about 7,000 Chilean refugees. In 1978,

the United States launched the Hemispheric 500 Program,

providing parole for several thousand Chilean and Argen-

tinean political prisoners. In the following year, Canada cre-

ated a new refugee category for “Latin American Political

Prisoners and Oppressed Persons.” In both cases, the stan-

dards for entry were higher than those for people from

Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe, where applicants were

fleeing communist regimes. During the 1970s, 17,600

Chileans immigrated to the United States, coming from

both sides of the political spectrum and often clashing in

their new country.

CHILEAN IMMIGRATION 57

After widespread international criticism for human

rights abuses, in 1990, Pinochet was forced to return the

country to civilian rule. Of more than 1 million Chileans

who were either exiled or forced to flee the country, about

10 percent settled in the United States. Between 1992 and

2002, the United States admitted 17,887 Chilean immi-

grants. Angered by American

COLD WAR

support for

Pinochet, many Chileans chose to emigrate elsewhere. Of

Canada’s 24,495 Chilean immigrants in 2001, almost

11,000 came between 1971 and 1980 and about 5,700

between 1991 and 2001.

Further Reading

Beilharz, E., and C. U. Lopez. We Were Forty-Niners! Chilean Accounts

of the Califor

nia Gold Rush. Pasadena, Calif.: Ward Ritchie, 1976.

Collier, S

imon, with William F. Sater. A History of Chile, 1808–1994.

Cambridge: Cambridge U

niversity P

ress, 1996.

Duran, Marcela. “Life in Exile: Chileans in Canada.” Multiculturalism

3, no

. 4 (1980): 13–16.

Hudson, Rex A. Chile: A Country Study. 3d ed. Washington, D.C.:

U.S. G

o

vernment Printing Office, 1995.

Kay, Diana. Chileans in Exile: Private Struggles, Public Lives.

Wolfeboro, N.H.: Longwood Academic, 1987.

Lope

z, Carlos U. Chilenos in California: A Study of the 1850, 1852,

and 1860 Censuses. S

an Francisco: R. and E. Research Associates,

1973.

M

oaghan, J

ay. Chile, Peru, and the California Gold Rush of 1849.

Berkeley: University of California Press, R. and E. Research Asso-

ciates, 1973.

Pereira Salas, Eugenio. Los primeros contactos entre Chile y los Estados

Unidos, 1778–1809. Santiago: Andres Bello, 1974.

Pozo, J

osé del. Los Chilenos del Quebec y los Estudios avanzados: M

emo-

rias y tesis sobre Chile en Canadá. Montreal: Publicació de PRO-

TACH, 1994.

R

ockett, Ian R. H. “Immigration Legislation and the Flow of Special-

ized Human Capital from South America to the United States.”

International Migration Review 10 (1976): 47–61.

Wright, Thomas C., and R

ody Oñate, eds. Flight fr

om Chile. Albu-

querque: U

niversity of New Mexico Press, 1998.

Chinese Exclusion Act (United States) (1882)

The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first measure to specifi-

cally ex

clude an ethnic group from immigrating to the

United States. It formed the basis of American anti-Asian

immigration policy and was not repealed until 1943, when

the United States and China became allies during World

War II (see W

ORLD

W

AR

II

AND IMMIGRATION

).

When the Chinese first came to California in large

numbers, in the 1850s in the wake of the gold rush, they

were generally well received as among “the most worthy of

our newly adopted citizens.” By the 1870s, they constituted

almost 10 percent of the population of California, but with

the economic hard times of the 1870s, many westerners

blamed the 100,000 Chinese immigrants for taking jobs and

depressing wages. Increasing agitation from the early 1870s

was for a time deflected by merchants, industrialists,

steamship companies, missionaries, and East Coast intellec-

tuals who argued in favor of the Chinese presence in Amer-

ica. By the late 1870s, politicians in the Midwest and East

took an interest in placating an increasingly violent white

labor force and thus were inclined to agree to limitations on

Chinese immigration. In addition to organized opposition

from labor groups such as the Workingmen’s Party,

RACISM

played a large role in anti-Chinese attitudes. Growing anti-

Chinese opposition led to passage of the P

AGE

A

CT

(1875)

and appointment of a Senate committee to investigate the

question of Chinese immigration (January 1876). In 1879,

Henry George published Progress and Poverty, one of the

most influential economic tracts of the 19th century

, in

which he concluded that the Chinese w

ere economically

backward and “unassimilable.” In the same year, President

Rutherford B. Hayes encouraged Congress to examine ways

of limiting Chinese immigration. After much debate and

many abortive bills, the United States and China signed the

Angell Treaty (1881), which modified the B

URLINGAME

T

REATY

(1868) and gave the United States authority to reg-

ulate the immigration of Chinese laborers. A bill was quickly

brought forward to exclude Chinese laborers for 20 years,

but it was vetoed by President Chester A. Arthur, who

argued that such a long period of exclusion would contra-

vene the articles of the Angell Treaty. Arthur reluctantly

signed a revised measure on May 6, 1882. Its major provi-

sions included

1. exclusion of all Chinese laborers for 10 years, start-

ing 90 days from enactment of the new law

2. denial of naturalization to Chinese aliens already in

the United States

3. registration of all Chinese laborers already in the

United States, who were still allowed to travel freely

to and from the United States

Chinese officials and their domestic servants were exempted

from the prohibition. In 1888, the S

COTT

A

CT

imposed new

restrictions on Chinese immigration. The exclusions were

extended in 1892 and again, for an indefinite period of time,

in 1902. As a result of the 90-day deferral period, almost

40,000 additional Chinese laborers entered the United States,

raising the Chinese population to about 150,000.

Further Reading

Chan, Sucheng, ed. Entry Denied: Exclusion and the Chinese Commu-

nity in America, 1882–1943. P

hiladelphia: Temple University

Pr

ess, 1991.

Daniels, Roger. Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Pol-

icy and I

mmigr

ants since 1882. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004.

Gy

ory, Andrew. Closing the Gate: Race, Politics, and the Chinese Exclu-

sion Act. Chapel H

ill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

58 CHINESE EXCLUSION ACT

Miller, Stuart C. The Unwelcome Immigrant: The American Image of the

Chinese, 1785–1882. Berkeley: University of California Press,

1969.

Rhoads, E

dward J. M. “‘White Labor’ vs. ‘Coolie Labor’: The ‘Chi-

nese Question’ in Pennsylvania in the 1870s.” Journal of Ameri-

can Ethnic H

istory 21 (Winter 2002): 3–33.

Takaki, R

onald. Strangers from a Different Shore. Boston: Little,

Br

own, 1989.

Chinese immigration

The Chinese were the first large Asian group to settle in

both the United States and Canada and proved integral to

the economic development of the North American west.

As visible minorities, they were also the first to suffer from

RACISM

as well as

NATIVISM

. The C

HINESE

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

(1882) in the United States and the C

HINESE

I

MMI

-

GRATION

A

CT

(1885) in Canada were the first pieces of

CHINESE IMMIGRATION 59

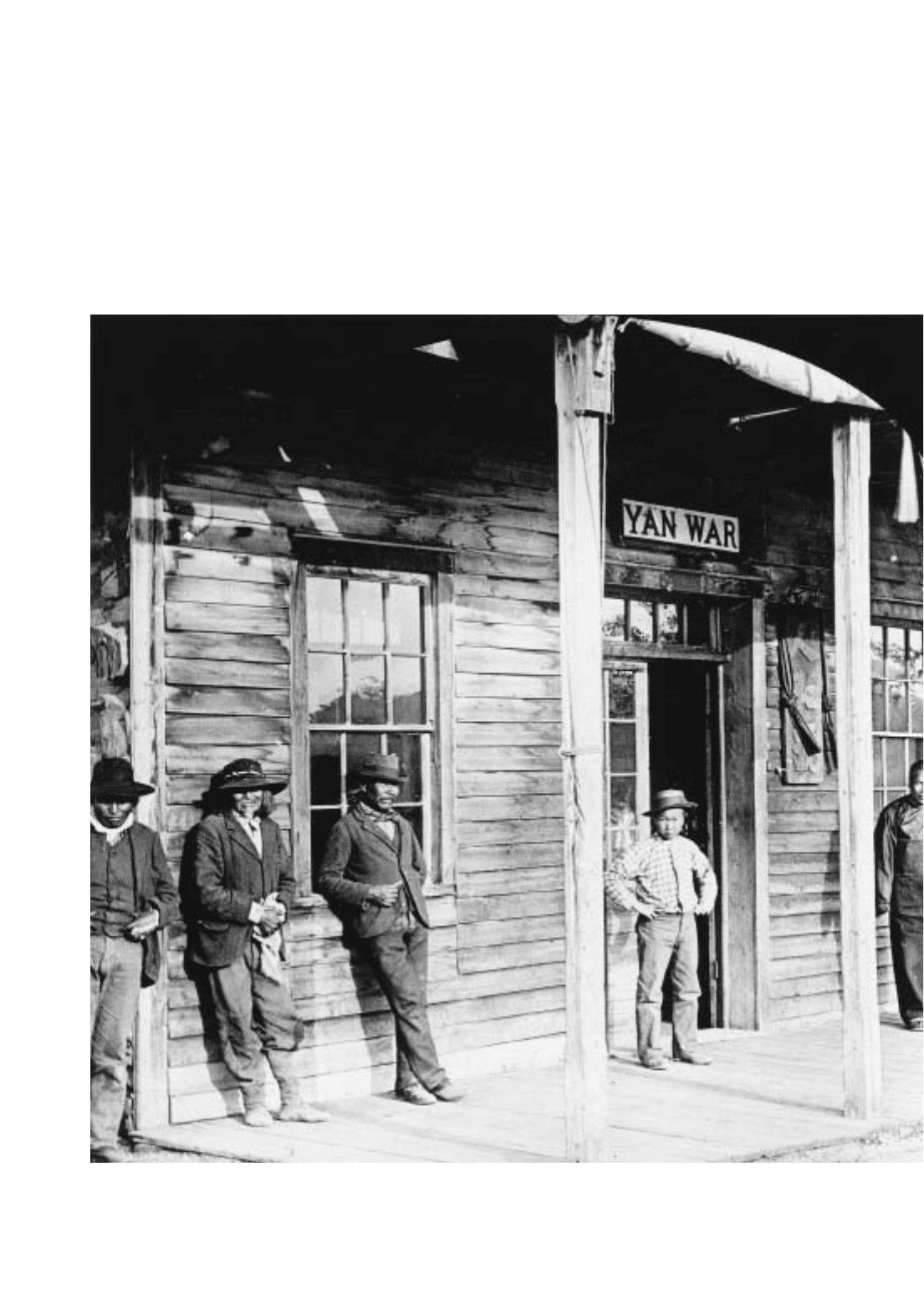

A Chinese store in the interior of the “upper country,” British Columbia, ca. 1910. Between 1881 and 1884, more than 17,000

Chinese immigrants arrived in Vancouver, most to work on the Canadian Pacific Railway. Fears of a “yellow” west led to Canada’s

first anti-immigrant legislation based on race, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885.

(National Archives of Canada/PA-122688)

immigration legislation in each country to deny entry on

the basis of race.

From the mid-1850s to 2002, more than 1.5 million

Chinese immigrated to the United States, not including

hundreds of thousands of ethnic Chinese from other coun-

tries. About 600,000 Chinese entered Canada during the

same period. Over time, the Chinese in North America

proved to be resilient, adaptable, and successful in moving

up the economic ladder. As a result, by the 1990s they were

often refused minority status in a variety of programs

emphasizing racial balancing. In the U.S. census of 2000

and the Canadian census of 2001, about 2.9 million Amer-

icans and 1.1 million Canadians claimed Chinese descent.

San Francisco was the early center of Chinese settlement in

the United States. During the 20th century, however, sig-

nificant Chinatowns were established in major cities across

the United States. According to the U.S. census of 2000,

New York City (536,966), San Francisco (521,645), and Los

Angeles (472,637) have the largest Chinese populations in

the United States. Toronto (435,685) and Vancouver

(347,985) have the largest Chinese populations in Canada

as recorded in the Canadian census of 2001.

China is the world’s largest country in population (1.3

billion in 2002) and third largest in landmass (3,696,100

square miles). It is bordered on the north by Russia, Korea,

and Mongolia; to the west by Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan,

Afghanistan, and India; to the south by Nepal, Bhutan,

India, Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam; and to the east by the

Pacific Ocean. Developing one of the world’s earliest great

civilizations along the Yellow River by about 1600

B

.

C

.,

China exerted from thereon broad cultural influence

throughout eastern and southeastern Asia, most notably in

Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Throughout its long imperial

rule, China’s political and cultural supremacy was seldom

questioned by either rulers or neighbors. Even when ene-

mies such as the Mongols (1279–1368) and the Manchus

(1644–1911) conquered China, they largely embraced its

(Han) culture, maintaining the country’s long traditions. It

was not until the 1830s that China’s encounter with the

West and its new industrial technologies led some to ques-

tion China’s traditional reliance upon the Confucian val-

ues of the ancient past. By the late 19th century, China

had been carved into spheres of European influence. The

Qing dynasty of the Manchus was so severely weakened

that the country was defeated by the much smaller but

rapidly modernizing Japan (Sino-Japanese War, 1894–95),

and the dynasty itself was overthrown by republican forces

in 1911. Throughout its history, China’s dense population

left it particularly vulnerable to the famines and floods that

frequently ravaged the country. This, coupled with China’s

economic superiority in Asia, helped establish an ongoing

tradition of migration that led to the establishment of large

Chinese communities throughout Southeast Asia. Thus,

when opportunities arose to migrate to North America,

immigrants responded within a traditional framework for

migration.

The first significant period of immigration to North

America came between 1849 and 1882, when some

300,000 young, impoverished, and mostly male peasants

came as contract laborers during the C

ALIFORNIA GOLD

RUSH

. The young men of coastal Guangdong (Canton)

Province, who suffered from increasing competition from

European manufactured goods, loss of jobs, and interethnic

conflicts, had both the means of learning of North Ameri-

can opportunities and access to the ships that would take

them there. Few made money for themselves in the gold-

fields, but they proved to be valuable laborers for large min-

ing corporations, and they frequently earned a living

providing mining camps with food, supplies, and a variety

of services. After the mines played out, the Chinese stayed to

work on railroad construction, swamp reclamation, and in

agriculture and fishing. They were considered ideal laborers

and constituted about 80 percent of the labor force of the

Central Pacific Railroad during the construction of the first

transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869. Prohibited

from becoming citizens, most planned to improve their

financial position, then eventually return to China, an atti-

tude reinforced by the rise of militant anti-Chinese senti-

ment throughout the West. By 1882, when Chinese

immigration was virtually prohibited, there were about

110,000 Chinese in the United States, most in California

and other western states.

The pattern of immigration and exclusion was remark-

ably similar in Canada, though on a smaller scale. Chinese

people first came in significant numbers to British

Columbia with the Fraser River gold rush of 1858. Within

two years their population was 4,000. After the goldfields

were exhausted, the Chinese increasingly became servants,

ran low-capital businesses such as laundries and restaurants,

and worked in agriculture and on the railroads. Between

1881 and 1884, it is estimated that 17,000 were brought in

to work on the Canadian Pacific Railway, more than half

directly from China, but a significant number from the

United States as well. As a result of local Canadian opposi-

tion, in 1885, the Chinese Immigration Act was passed,

imposing a $50 head tax on Chinese immigrants, thus dras-

tically reducing their entry.

From 1882 until 1943, generally only students, mer-

chants, and diplomats were allowed to come freely to the

United States. With Canadian restrictions less severe, some

laborers continued coming to Canada with the expectation

of meeting relatives or of illegally entering the United States.

Between 1886 and 1911, more than 55,000 paid the head

tax, but many of these either returned to China or migrated

to the United States. Due to the initial gender imbalance (27

men to one woman in 1890), prohibitions on interracial

marriage, and immigration restrictions, the vast majority of

Chinese women in North America were forced to become

60 CHINESE IMMIGRATION

prostitutes, most sold into sexual slavery by impoverished

Chinese families. This unusual social structure was usually

hidden away in “Chinatowns,” where most Chinese lived

and did business and where few whites, save missionaries

and public officials, ever ventured. This social exclusion was

strengthened in Canada with passage of a Chinese exclu-

sion law of 1923, based on the doctrine that the two races

were wholly different and could not work toward the same

goals. Though making some provision for Chinese who had

entered under the head tax to travel between China and

Canada, the new regulations allowed virtually no new immi-

grants between 1924 and 1946.

World War II (1939–45) encouraged some change in

both American and Canadian attitudes toward the Chi-

nese. With China an important ally against Imperial Japan,

and thousands of Chinese Americans volunteering for mil-

itary service and working in defense-related industries, in

1943, Congress repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Although the number of allowable immigrants remained

small, Chinese aliens did gain the right to naturalization.

The W

AR

B

RIDES

A

CT

brought some 6,000 into the coun-

try outside the quota, and various Refugee Acts associated

with the

COLD WAR

enabled another 30,000 mostly well-

educated Chinese to enter. In Canada, Chinese were

granted access to more professions, and it was made easier

for them to acquire citizenship. The Chinese Immigration

Act of 1947 and Order in Council P.C. 2115 did not rep-

resent a major change in immigration policy, however, as it

only allowed Chinese Canadians who were citizens to

bring their spouses and minor children into the country.

During the 1940s, only about 5 percent were Canadian or

British citizens.

The I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965

finally removed race as a barrier to immigration to the

United States, opening a new era to which the Chinese

eagerly responded. In addition to large numbers coming to

reunite with family members, some 250,000 highly edu-

cated scientists, engineers, and intellectuals migrated to the

United States between 1965 and 2000 to take advanced

degrees, with most remaining in the country. Tens of thou-

sands emigrated from Taiwan (see T

AIWANESE IMMIGRA

-

TION

) and Hong Kong, principally for education and

economic opportunities. Normalization of diplomatic rela-

tions with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1979

opened a new immigration market. Following the end of the

Vietnam War in 1975, more than 1 million Vietnamese,

Laotian, and Cambodian refugees entered the United States;

perhaps one-third were ethnic Chinese, who tended to settle

in Chinatowns. Finally, during the 1980s and 1990s, the

smuggling of Chinese laborers from the PRC became a

growing problem. In 2000, the Immigration and Natural-

ization Service estimated that there were about 115,000

unauthorized Chinese living in the United States, the largest

number for any country outside the Western Hemisphere.

Between 1992 and 2002, more than 700,000 Chinese from

the PRC, Hong Kong, and Taiwan immigrated to the

United States. Canada’s

IMMIGRATION REGULATIONS

of

1967 similarly eliminated racial considerations in immigrant

selection, leading to an upsurge in Chinese immigration,

most coming from Hong Kong. Between 1991 and 2001,

more than 400,000 Chinese immigrated to Canada, making

them the fastest growing visible minority in the country.

Hong Kong was the number one source country for Cana-

dian immigration throughout most of the 1990s and was

only replaced by the People’s Republic of China in 1997 as

Hong Kong’s position within the PRC was regularized. Tai-

wan also placed in the top six source countries during most

of the 1990s.

See also A

NGEL

I

SLAND

.

Further Reading

Chan, Anthony. Gold Mountain: The Chinese in the New World. Van-

couver

, Canada: New Star Books, 1983.

Chan, Sucheng. Entry Denied: Exclusion and the Chinese Community in

A

merica, 1882–1943. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991.

Chang, Iris. The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. New York:

Viking P

ress, 2003.

Chen, Yong. Chinese San Francisco

, 1850–1943: A Trans-Pacific Com-

munity. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2000.

Chin, Ko-lin. Smuggled Chinese: Clandestine Immigration to the United

States. P

hiladelphia: Temple University Press, 1999.

Daniels, Roger. Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United

S

tates since 1850. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988.

Hing, B

ill Ong. Making and Remaking Asian America through Immi-

gration P

olicy, 1850–1990. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University

Press, 1993.

Lai, David Chuenyan. C

hinatowns: Towns within Cities in Canada.

Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia Press, 1988.

Lai, H

im Mark. Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities

and Institutions. W

alnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira Press, 2004.

Lee, Erika. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclu-

sion E

ra, 1882–1943. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina

Press, 2003.

Lee Tunh-hai. A History of Chinese in Canada. Y

angmingshan, Taiwan:

Zhonghua dadian bian yin hui, 1967.

Ling, Huping. Surviving on the Gold Mountain: A History of Chinese-

American

Women and Their Lives. New York: State University of

New Yor

k Press, 1998.

Liu, Po-chi. A History of the Chinese in the United States of America,

1848–1911. T

aipei: Commission of Overseas Chinese, 1976.

McClain, Charles J. I

n Search of Equality:

The Chinese Struggle against

Discrimination in Nineteenth-Century America. Berkeley: Univer-

sity of California Pr

ess, 1994.

McCunn, Ruthanne Lum. Chinese American Portraits. San Francisco:

Chronicle Books, 1988.

M

e, Dianne, Mark Lin, and Ginger Chih. A Place Called Chinese

A

merica. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt, 1985.

Miller

, Stuart C. The Unwelcome Immigrant: The American Image of the

Chinese, 1785–1882. Berkeley: University of California Press,

1969.

61CHINESE IMMIGRATION 61

Pan, Lynn, ed. The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas. Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999.

———. Sons of the Yellow Emperor: A History of the Chinese Diaspora.

Boston: Little, B

rown, 1990.

Saxton, Alexander. The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chi-

nese Mo

vement in California. Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1995.

S

keldon, Ronald. “Migration from China.” Journal of International

Affairs 49, no. 2 (1996): 434–455.

Steiner

, S

tan. Fusang: The Chinese Who Built America. New York:

H

arper and Row, 1979.

Tan, Jin, and Patricia E. Roy. The Chinese in Canada. Ottawa: Cana-

dian H

istorical Association, 1985.

T

sai, Shih-shan Henry. China and the Overseas Chinese in the United

S

tates, 1868–1911. F

ayetteville: University of Arkansas Press,

1983.

———. The Chinese Experience in America. Bloomington: Indiana

U

niv

ersity Press, 1986.

Tung, William L. The Chinese in America, 1820–1973: A Chronology

and Fact Book. Dobbs F

erry, N.Y.: Oceana Publications 1974.

W

ickberg, Edgar, ed. From China to Canada: A History of the Chinese

Communities in Canada. T

oronto: McClelland and Stewart,

1982.

Z

eng

Yi and Zhang Qinwu. “Conditions in China Influencing Out-

migration.” In The Silent Debate: Asian Immigration and Racism

in Canada. Eds. Eleanor Laquian, Aprodicio Laquian, and Terry

McGee. Vancouver, Canada: Institute of Asian R

esearch, Uni-

versity of British Columbia, 1998.

Chinese Immigration Act (Canada) (1885)

Incorporating recommendations from the Royal Commis-

sion on Chinese I

mmigration (1884–85), the Chinese

Immigration Act was the first Canadian legislation to for-

mally limit immigration based on race. While not prohibit-

ing immigration altogether, its severe restrictions formed the

basis of official Canadian policy toward the Chinese until

after World War II.

Protests began almost immediately after Chinese labor-

ers started to arrive in large numbers to work on the Cana-

dian Pacific Railway in the early 1880s. More than 17,000

arrived in Vancouver alone between 1881 and 1884.

Although white Canadians complained that the Chinese

were dirty, disease ridden, and lacking morals, employers

were not slow to recognize their value, as they worked for

30–50 percent less than European laborers, who were in any

case in short supply. Although Prime Minister John Mac-

donald was, like most Canadians, opposed to permanent

Chinese settlement, as he told the House of Commons,

“Either you must have labour or you can’t have the railway.”

Following the recommendations of the Royal Commission,

the Chinese Immigration Act imposed a $50 head tax on

Chinese laborers and limited ships to one Chinese immi-

grant per 50 tons of cargo. Excluded from the head tax were

tourists, students, diplomats, and merchants. The measure

was amended in 1908, limiting head tax exclusions and

expanding the list of prohibited immigrants. A revised act of

1923 eliminated the head tax but instituted exclusionary

clauses so broad that Chinese immigration was virtually

halted until repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act in 1947:

During that period, only 15 Chinese were legally permitted

to immigrate to Canada.

Further Reading

Kelley, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

History of C

anadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

T

oronto Press, 1998.

Roy, Patricia E. “A Choice between Evils: The Chinese and the Con-

struction of the Canadian Pacific Railway in British Columbia.”

In The CPR West: The Iron Road and the Making of a Nation. Van-

couv

er and

Toronto: Douglas and McIntyre, 1984.

Wickberg, Edgar, ed. From China to Canada: A History of the Chinese

Communities in C

anada. T

oronto: McClelland and Stewart,

1982.

CIC See D

EPARTMENT OF

M

ANPOWER AND

I

MMIGRATION

.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada See

D

EPARTMENT OF

M

ANPOWER AND

I

MMIGRATION

.

Civil Liberties Act (United States) (1988) See

J

APANESE INTERNMENT

,W

ORLD

W

AR

II

AND

IMMIGRATION

.

Civil Rights Act (United States) (1964)

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it illegal to discriminate

in employment or the use of public facilities on the basis of

race, color, religion, gender, or national origin. It also out-

lawed poll taxes and arbitrary literacy tests that had tradi-

tionally been used to exclude African Americans and other

minorities from voting. The act gave the attorney general

broad powers to bring legal suit against violators who con-

tinued to practice segregation. Finally, the act provided for

creation of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis-

sion (EEOC) to assist in assuring fairness in employment

practices.

Though the Civil Rights Act marked the legislative

high point of the Civil Rights movement led by African

Americans, its provisions were equally applicable to immi-

grants. A changing social consciousness based on the jus-

tice of the Civil Rights movement and the imperatives of

the

COLD WAR

helped pave the way for the nonracially

based I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965. As

Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy observed to Congress

6262 CHINESE IMMIGRATION ACT

in 1964, except in immigration, “Everywhere else in our

national life, we have eliminated discrimination based on

national origins.”

Further Reading

Abraham, Henry J., and Barbara A. Perry. Freedom and the Court. 6th

ed. Ne

w York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Bell, Derrick A., Jr. Race, Racism, and American Law. 2d ed. Boston:

Little, B

r

own, 1980.

Bullock, Charles S., III, and Charles M. Lamb. Implementation of

C

ivil Rights P

olicy. Monterey, Calif.: Brooks-Cole, 1984.

Coast Guard, U.S.

The Coast Guard is the part of the U.S. Armed Forces

responsible for enforcing maritime laws, search-and-rescue

operations at sea, interdictment of drugs and illegal aliens,

protection of the marine environment, and protection of

maritime borders. It operates as a branch of the D

EPART

-

MENT OF

H

OMELAND

S

ECURITY

in peacetime but is inte-

grated with the U.S. Navy during time of war. Organized

along similar lines, the Coast Guard and navy routinely

cooperate in Greenland, Iceland, and other Arctic areas.

Coast Guard vessels and personnel have provided naval sup-

port in all U.S. wars, including the war against Iraq (2003).

The Coast Guard was founded in 1790, although it did

not take its present name until 1915 when the Revenue Cut-

ter Service and the Life-saving Service merged. Responsibil-

ities of the Light House Service were transferred to the Coast

Guard in 1939, and those of the Bureau of Marine Inspec-

tion and Navigation in 1946. The largest peacetime opera-

tion of the guard was during the M

ARIEL

B

OATLIFT

of

1980–81, when more than 125,000 Cuban refugees sailed

from their homeland to Florida, most in crowded small craft

not suited to sea voyages. Coast Guard resources were called

in from bases along the East Coast, and 900 reservists were

called to active duty. In the wake of the S

EPTEMBER

11,

2001, attacks, supervision of the Coast Guard was trans-

ferred in 2003 from the Department of Transportation to

the newly created Department of Homeland Security.

Further Reading

Canney, Donald L. U.S. Coast Guard and Revenue Cutters,

1790–1935. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1995.

J

ohnson, R

obert Erwin. Guardians of the Sea: History of the United

States Coast G

uard, 1915 to the Present. Annapolis, Md.: Naval

Institute P

ress, 1987.

Colbert, Jean-Baptiste (1619–1683) statesman

Jean-Baptiste Colbert was a member of the Great Council of

State and the French king Louis XIV’s intendant de finance

(superintendant of finance). He was responsible for imple-

menting mer

cantile r

eforms designed to extract New World

wealth for the French Crown. After the failures of the C

OM

-

PAGNIE DE LA

N

OUVELLE

F

RANCE

(Company of New

France), he established the Compagnie des Indes Occiden-

tals (French West Indies Company) to govern N

EW

F

RANCE

and compete with England and Spain in the Americas.

Though generally successful in managing French finances,

he was never able to attract large numbers of French settlers

to New France.

Born into a prosperous family from Reims, Colbert

became an agent for Cardinal Mazarin in 1651. In 1661, he

was appointed superintendant of finance and quickly became

the most important adviser to Louis XIV, gradually taking

charge of the navy, the merchant marine, commerce, the

royal household, and public buildings. Colbert worked tire-

lessly to repair France’s financial structure, wrecked by years

of corruption and neglect. He made the tax system more effi-

cient, expanded industry, and promoted the export of French

luxury goods. Through strict regulation and supervision, he

tightened royal control over finance and built one of the

strongest navies in Europe. The American colonies had suf-

fered particular neglect during the previous 40 years. In order

to revive American self-sufficiency, Colbert appointed J

EAN

T

ALON

as intendant of New France, and together they pro-

moted immigration, economic diversification, and trade with

the West Indies. In the last years of Colbert’s life, expensive

wars promoted by his rival, the war minister marquis de Lou-

vois, undermined many of the benefits of his financial reor-

ganization. Cold and unpopular with the public, Colbert was

nevertheless an incredibly efficient administrator who

enhanced French power in the Americas.

Further Reading

Cole, Charles Woolsey. Colbert and a C

entury of French Mercantilism.

2 vols. Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1939.

Eccles, W

. J. Canada under Louis XIV, 1663–1701. Toronto: McClel-

land and S

tewart, 1964.

Goubert, Pierre. Louis XIV and Twenty Million Frenchmen. 1966.

R

eprint, N

ew York: Pantheon Books, 1970.

Murat, Ines. Colbert. Charlottesville: University P

r

ess of Virginia,

1984.

cold war

The period of intense political and ideological struggle

between democratic countries led by the United States and

the Soviet Union (1945–91) and its communist satellites is

often referred to as the cold war. As the Soviet Union sought

to surround itself with friendly communist states in the

wake of the enormous devastation of World War II

(1939–45), the United States aided anticommunist, right-

wing governments in all parts of the world. Ideological dif-

ferences thus permeated the processes of modernization and

decolonization of European empires. Millions of people

were displaced in the struggle between communism and

democracy and sought permanent haven in North America.

63COLD WAR 63