Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Most of these Mexicans worked in agriculture in either

Texas or California, but their numbers were also significant

in Kansas and Colorado, and migrants began to take more

industrial jobs in the upper Midwest and Great Lakes

region, leading to a general dispersal throughout the coun-

try. Between 1900 and the onset of the Great Depression in

1930, the number of foreign-born Mexicans in the United

States rose from 100,000 to 639,000. With so many Amer-

ican citizens out of work, more than 500,000 Mexicans were

repatriated during the 1930s. When the United States

entered World War II in December 1941, the need for labor

was urgent, leading to passage of the Emergency Farm Labor

Program in August 1942. The Bracero Program, as it was

commonly called, emerged from an agreement between the

U.S. and Mexican governments with five major provisions:

1. Mexicans would not engage in military service

2. Mexicans would not suffer discrimination

3. Workers would be provided wages, transportation,

living expenses, and repatriation in keeping with

Mexican labor laws

4. Workers would not be eligible for jobs that would

displace Americans

5. Workers would be eligible only for agricultural jobs

and would be subject to deportation if they worked

in any other industry

Despite wages of only 20¢ to 50¢ per day and deplorable liv-

ing conditions in many areas, braceros both legal and illegal

continued to come, finding the wages sufficient to enable

them to send money home to their families.

The original Bracero Program ended in 1947 but was

extended in various ways until 1964. During the 22 years

of its existence, almost 5 million braceros worked in the

United States, contributing substantially to the agricultural

development of the United States and remitting more than

$200 million to relatives in Mexico. The growth of liberal

political power in the United States, increased mechaniza-

34 BRACERO PROGRAM

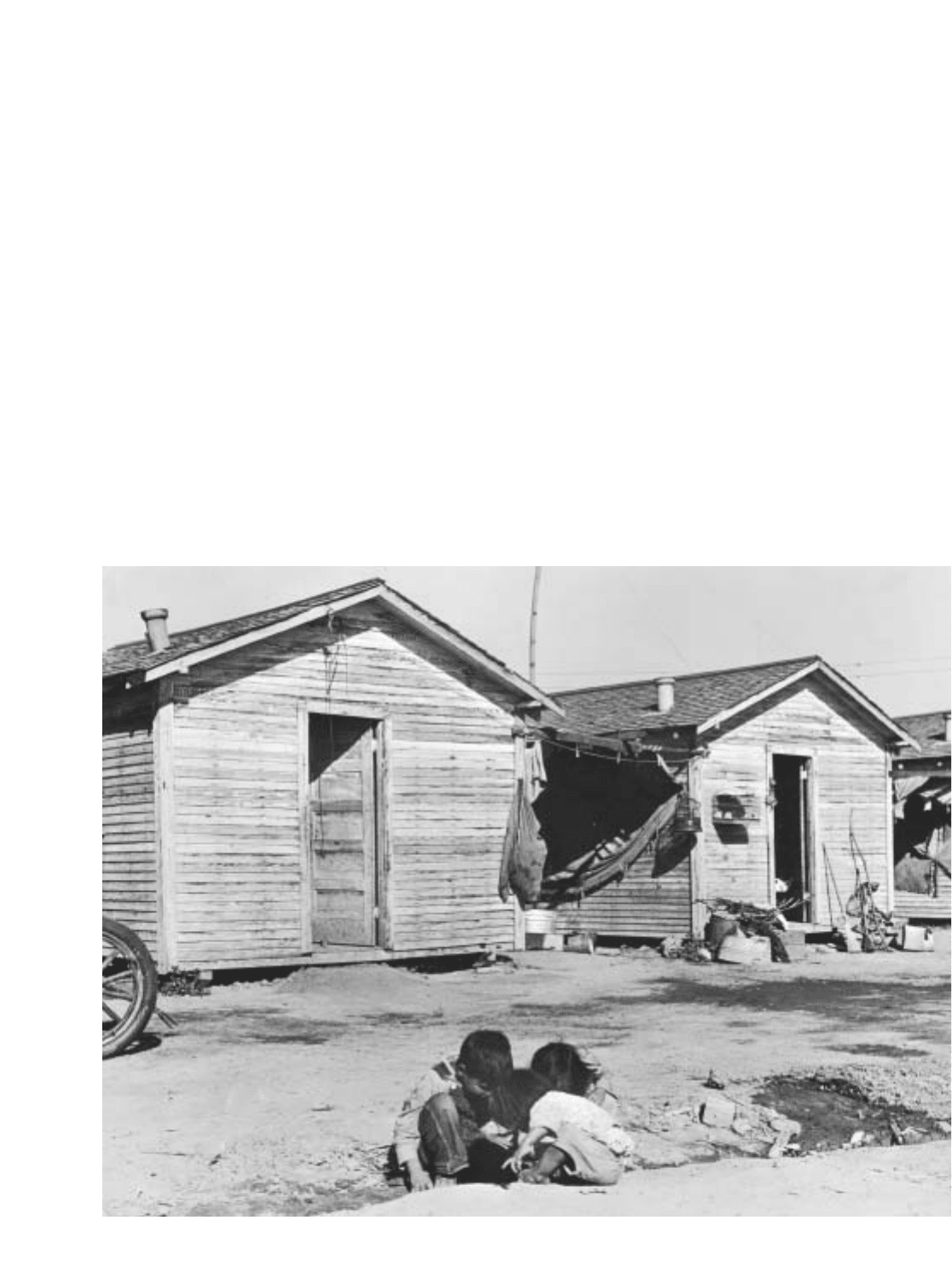

Company housing for Mexican migrant laborers, Corcoran, California, San Joaquin Valley, 1940 (National Archives #NWDNS-83-G-4147b)

tion in agriculture, and a rising demand for labor in Mexico

all contributed to the ending of the program in 1964.

Further Reading

Briggs, Vernon M., Jr. “Foreign Labor Programs as an Alternative to

Illegal I

mmigration: A Dissenting View.” In The Border That

Joins: Mexican M

igrants and U.S. Responsibility. Ed. Peter G.

B

rown and Henry Shue. Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Littlefield,

1983.

Calavita, Kitty. Inside the S

tate: The Bracero Program, Immigration, and

the I.N.S. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Driscoll, B

arbara A. The Tracks North: The Railroad Bracero Program of

Wor

ld War II. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999.

Galar

za, Ernest. Merchants of Labor: The Mexican Bracero History.

Santa Barbara, Calif.: McNally and Loftin, 1964.

G

amboa, E

rasmo. Mexican Labor and World War II: Braceros in the

Pacific Nor

thwest, 1942–1947. Austin: University of Texas Press,

1990.

Rasmussen, W

ayne D. A H

istory of the Emergency Farm Labor Supply

P

rogram, 1943–1945. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1951.

Bradford,William (1590–1656) religious leader and

colonizer

One of the chief architects of the Pilgrim migration from

Holland to Plymouth in 1620 (see P

ILGRIMS AND

P

URI

-

TANS

;M

ASSACHUSETTS COLONY

), William Bradford served

as Plymouth Colony’s governor between 1622 and 1656

(excepting 1633–34, 1636, 1638, and 1644). His wise lead-

ership inspired confidence and helped ensure the survival of

England’s second colony in America.

Bradford was born in Austerfield, Yorkshire, into a yeo-

man farming family. He joined a separatist congregation as

a young man and in 1608 followed John Robinson to Ley-

den, Holland, to avoid religious persecution by King James

I. Though granted complete freedom of conscience there,

the separatists feared that their families were losing their

English identity and began searching for a new home. In

1617, Bradford served on a committee to arrange migration

to America and in 1620 was one of 102 Pilgrims to set sail

for the New World aboard the Mayflower, an expedition

funded b

y an E

nglish joint-stock company with only nom-

inal interest in the Pilgrims’ religious cause. Bound with a

royal patent to settle in Virginia, the Pilgrims had no legal

standing in New England, where they landed as the result of

a navigational error. This led Bradford and the other men

in the group to sign the Mayflower Compact (November

11), establishing “a civil body politick” to protect the colony

from anarchy.

After the 1621 death of John Carver, the colony’s first

governor, Bradford was elected to the position. As leader of

a small band of poor settlers, he faced many difficulties. In

1623, he abandoned Pilgrim communalism as detrimental

to initiative; in 1636, he encouraged the codification of local

laws and a basic statement of rights. Bradford led the Pil-

grims to honor their financial commitments, though it took

more than 20 years to repay their English investors. Much of

Plymouth’s success owed to Bradford’s religious tolerance

and good relations with the native peoples of the region. His

historical masterpiece, Of Plimmoth Plantation, is one of

the most vivid accounts of early settlement in America. I

t

was written betw

een 1630 and 1650, but not published in

full until 1856.

Further Reading

Bradford, William. Of Plimmoth Plantation. Ed. Charles P. Deane.

Boston: Massachusetts H

istorical Society, 1856.

Langdon, George D. Pilgrim Colony: A History of New Plymouth,

1620–1691. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1966.

S

mith, Bradford. Bradford of Plymouth. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott,

1951.

Brazilian immigration

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, few Brazil-

ians immigrated to North America, as their country was

actively promoting immigration to Brazil to develop the

untapped resources of the country. As late as 1960, only

27,885 Americans claimed Brazilian descent. By 2000, how-

ever, the number had risen to 181,076. In 2001, 9,710

Canadians claimed Brazilian descent. Most observers place

the actual figures in both countries at almost twice that

number as a result of illegal immigration. New York City has

the largest Brazilian population in North America, with the

greatest concentration in Queens. Most Canadian Brazilians

live in Toronto and southern Ontario.

Brazil occupies 3,261,200 square miles of the eastern

half of South America between 5 degrees north latitude

and 33 degrees south latitude. French Guiana, Suriname,

Guyana, and Venezuela lie to the north; the Atlantic

Ocean, to the east; Uruguay, to the south; and Colombia,

Peru, Bolivia, and Paraguay to the west. The Amazon River

basin is located in the northern part of the country and is

densely covered in tropical forests. In the northeast, flat

arable land provides a home for the majority of the esti-

mated 174,468,575 people who live in Brazil. Over 10

million people live in both São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Over half the population, about 55 percent, is descended

from Portuguese, German, Italian, and Spanish immi-

grants. About 6 percent is black, and 38 percent is of

mixed black and white ancestry. Most Brazilian immi-

grants to North America have been of European descent,

often representing the well educated seeking economic

opportunities in a time of domestic economic stress.

Roman Catholicism is practiced by approximately 70 per-

cent of the population.

The Atlantic seaboard of Brazil was colonized by Por-

tugal in the 16th century. Settlers brought African slaves

BRAZILIAN IMMIGRATION 35

into the country until 1888 when slavery was abolished.

Brazil declared its independence from Portugal in 1822 and

was ruled by an emperor until 1889, when a republic was

proclaimed. Beginning in 1930, Brazil was ruled by mili-

tary leaders, excepting a 19-year span of democratic regime

from 1945 to 1964. Democracy was returned to Brazil in

the presidential elections of 1985.

Immigration figures are unreliable. Prior to 1960 in

the United States and 1962 in Canada, Brazilians were

counted collectively as “South Americans” or in some other

general category, making it impossible to distinguish exact

numbers for particular countries. It has been estimated that

about 50,000 Brazilians legally entered the United States

prior to 1986, and about 15,000 entered Canada.

Throughout the 20th century Brazil’s economy grew

to become one of the largest in the world, substantially

based on development of resources in the vast Amazonian

rain forest. Most of the early immigration to Canada was

in some way related to the close economic ties between

large Canadian corporations and the developing Brazilian

economy. Companies including Brascan, Alcan Alu-

minum, and Massey-Ferguson invested billions of dollars

in Brazil in the four decades following World War II

(1939–45), and Brazil remained Canada’s third leading tar-

get country for investment, behind only the United States

and Great Britain. By 1951, Canada was the second lead-

ing investor in Brazil, behind only the United States.

When the economic boom collapsed in 1981, Canadian

companies began to pull out of the country. By 1986, their

share of foreign holdings there had dropped from 30 per-

cent to 5 percent.

In the midst of considerable wealth, much of Brazil

remained in poverty, even before the economic collapse of

the 1980s. The return of a democratic government in 1985

made emigration easier, leading as many as 1.4 million

Brazilians to leave the country between 1986 and 1990.

Whereas many Brazilian immigrants prior to the mid-

1980s were from the professional or upper classes, most

after 1986 were small entrepreneurs or workers, seeking

fresh economic opportunities. Given the continued weak-

ness of the economy into the 21st century, many observers

believe that Brazilian immigration to North America will

continue to grow significantly. Some have estimated that

in 2000 there were as many as 350,000 Brazilians in the

United States, half of them illegally. The official govern-

ment estimate of the unauthorized Brazilian resident pop-

ulation in 2000 was 77,000, up from 20,000 in 1990 and

almost certainly significantly lower than the actual num-

ber. Between 1992 and 2002, more than 63,000 Brazil-

ians entered the United States legally. Of Canada’s 11,700

Brazilian immigrants in 2001, more than half (5,995)

entered the country between 1991 and 2001. Brazilian

immigration to both the United States and Canada grew

from the late 1990s onward.

Further Reading

Burns, E. Bradford. A History of Brazil. 3d ed. New York: Columbia

U

niversity Press, 1993.

Canak, W. L., ed. Lost Promises: Debt, Austerity, and Development in

Latin A

merica. B

oulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1989.

D

aMatta, Roberto. Carnavals, Rogues, and Heroes: An Interpretation

of the Br

azilian Dilemma. Trans. John Drury. Notre Dame, Ind.:

University of N

otre Dame Press, 1991.

Goza, Franklin. “Brazilian Immigration to North America.” Interna-

tional M

igr

ation Review 28 (Spring 1994): 136–152.

McDo

wall, Duncan. The Light: Brazilian Traction, Light and Power

Company L

imited, 1899–1945. Toronto: University of Toronto

Pr

ess, 1988.

Margolis, Maxine L. Little Brazil: An Ethnography of Brazilian Immi-

g

r

ants in New York City. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University

Press, 1994.

———. “

Transnationalism and Popular Culture: The Case of Brazil-

ian Immigrants in the United States.” Journal of Popular Culture

29 (1995): 29–41.

Britannia colony See B

ARR COLONY

.

British immigration

In the U.S. census of 2000, more than 67 million Americans

claimed British descent (English, Irish, Scots, Scots-Irish,

Welsh), while in the Canadian census of 2001, almost 10

million reported British ancestry. From the time of the first

permanent British presence in the New World at

Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, until 1900, British immi-

grants outnumbered all others in the United States and

Canada. And though the French took the lead in settling

A

CADIA

and Q

UEBEC

, the transfer of N

EW

F

RANCE

to

Britain at the conclusion of the S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

in 1763

spelled the end of significant French immigration. Between

1783 and 1812, the lands of modern Canada were flooded

with Loyalists and land seekers from the newly formed

United States of America. Economic distress and famine in

Ireland led to the emigration of some 5 million Irish

between 1830 and 1860, most choosing to go to the United

States or Canada. By the time Canada took its first post-

confederation census in 1871, 26 percent of Canadians were

of Scottish descent; 24 percent, Irish; and 20 percent,

English. By the time other immigrant groups overtook the

British in numbers immigrating to the United States,

around the turn of the 20th century, the British culture pat-

tern had been firmly established as the American model. In

Canada, the early French enclave of Quebec became increas-

ingly isolated as British customs and institutions took root

throughout the remainder of Canada.

British is an imprecise but useful term to describe four

major ethnic gr

oups that inhabited the two largest of the

British I

sles, Britain and Ireland. In ancient times, the

islands were inhabited by Celtic peoples, who were the

36 BRITANNIA COLONY

ancestors of the Scots, Welsh, and Irish. After 500 years of

Roman rule, in the fifth century, Britain was overrun by the

Nordic Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, who formed the basis of

the modern English peoples. In the medieval period, the

islands were ruled by various Irish, English, Welsh, Scot-

tish, and Danish (Viking) kings. During the 11th century,

French-speaking Normans conquered England but were

gradually absorbed into the old Anglo-Saxon traditions of

the country and by the 15th century had become fully

English in culture. Between the 9th and 14th centuries,

English kings consolidated control over the Danes and

Welsh, gained considerable influence over the Scottish

monarchy, and made inroads into eastern Ireland. During

the 17th century, England expanded into the New World,

establishing colonies along the Atlantic seaboard of North

America and throughout the Caribbean, as well as in the

Indian Ocean. England also finally brought northeastern

Ireland (U

LSTER

) under its control, formally annexing the

region in 1641. As early as the 16th century, the English

government began parceling out confiscated Irish lands to

caretakers willing to undertake the settlement of loyal

English or Scottish farmers, though their numbers remained

small until the 17th century. Between 1605 and 1697, it is

estimated that up to 200,000 Scots and 10,000 English

resettled in Ireland. Most settlers in the early stages were

poverty-stricken Lowland Scots. From the 1640s, however,

an increasing number were Highland Scots.

In 1603, the Scottish and English crowns were joined

under James VI of Scotland (James I of England), and by

1707, Scotland and England agreed to The Act of Union,

creating a new state named Great Britain. After the disas-

trous loss of the thirteen colonies during the A

MERICAN

R

EVOLUTION

(1775–83) and a brief period of Irish leg-

islative independence from 1782, Ireland’s parliament was

abolished, in 1801 and the country was administratively

united with Great Britain, forming the United Kingdom of

Great Britain and Ireland. Between the late 18th and the

mid-19th centuries, Britain was the leading industrial and

economic power in the world, which in part led to the cre-

ation of the largest colonial empire on earth. At the start of

the 20th century, Great Britain ruled Ireland, Canada,

South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, much of tropi-

cal Africa, India, and island and coastal regions throughout

the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and the Caribbean and

Mediterranean Seas. As a result of the Anglo-Irish War

(1919–21), the Irish Free State was created in southern Ire-

land, nominally under British direction but gradually

emerging as a fully independent nation, the Republic of

Eire, by 1937. The devastation of two world wars led to a

relative economic decline during the 20th century and a

gradual dismemberment of the empire between the 1940s

and the 1960s. The United Kingdom, or UK—often

referred to simply as Britain or Great Britain—joined the

European Community in 1973. The weak economy of the

1970s gave way to a booming growth in the 1980s under

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

There was no typical British immigrant to North Amer-

ica. Immigrants were English, Welsh, Scots, Scots-Irish, and

Irish. Some came as proprietors or representatives of the gov-

ernment, some as soldiers, some as seekers of religious free-

dom, some as indentured servants (see

INDENTURED

SERVITUDE

), and some as paupers. Most came to better their

economic circumstances in some way, driven by overcrowd-

ing and poor economic conditions in Britain. The British

came in four waves, each prompted by a peculiar set of cir-

cumstances. After unsuccessfully seeking reforms in the

Church of England, about 21,000 Puritans migrated to

Massachusetts, mainly from East Anglia, during the 1630s.

During the mid-17th century, about 45,000 Royalists,

including a large number of indentured servants, emigrated

from southern England to Virginia. During the late 17th

and early 18th centuries, about 23,000 settlers, many of

them Quakers, emigrated from Wales and the Midlands to

the Delaware Valley. Finally, in the largest migration, during

the 18th century, about 250,000 north Britons and Scots-

Irish immigrated, more than 100,000 of them from Ireland,

many settling along the Appalachians.

It is estimated that more than 300,000 Britons immi-

grated to America between 1607 and 1776, and a large nat-

ural increase led to a white population of some 2 million by

the time of the American Revolution, half of them English

and most of the remainder Scots, Scots-Irish, or Welsh. Nei-

ther the French before 1763 nor the British in the following

two decades had much success in attracting settlers to the

Canadian colonies. The population of the entire Canadian

region at the end of the American Revolution was about

140,000, most of whom were French and accounted for by

a high rate of natural increase. But Britain’s loss of the Amer-

ican colonies led to a dramatic demographic shift in its

remaining North American colonies. Before the end of the

1780s, 40,000–50,000 Loyalists left the new republic for

N

OVA

S

COTIA

, N

EW

B

RUNSWICK

, and Quebec. In addi-

tion, another several thousand Americans seeking better

farmlands moved to western Quebec. As a result of this great

influx of largely English-speaking settlers, in 1791, Quebec

was divided into Upper Canada (Ontario) and Lower

Canada (Quebec), roughly along British and French lines

of culture.

The French Revolution, French Revolutionary Wars,

and Napoleonic Wars (1789–1815) led to a lull in immi-

gration, but economic recession in England and Ireland led

to a steady immigration from the 1820s, culminating in the

mass migration of the 1840s and 1850s in the wake of a

potato famine in Ireland. Between 1791 and 1871, the pop-

ulation of British North America jumped from 250,000 to

more than 3 million, more than one-quarter of it Irish. By

1851, the largely British population of Upper Canada finally

surpassed that of Lower Canada, and 10 years later, the

BRITISH IMMIGRATION 37

French-Canadian population of Lower Canada dipped

below 80 percent.

Despite the vast influx of immigrants, emigration

from Canada to the United States was a routine feature

throughout the 19th century. Agricultural crises, rebel-

lions, and the difficulty of obtaining good farmland led

more than 300,000 people to migrate south of the border.

The outmigration became even more pronounced after

1865. Despite government policies actively encouraging

British immigration, until the turn of the 20th century,

more emigrants left Canada than those who entered, and

a large number of these emigrants were British. Beginning

in 1880, control of immigration fell under the auspices of

the Canadian high commissioner, who began to promote

immigration more aggressively, sending out immigration

agents, who arranged lectures and organized fairs, and

advertising throughout Britain. Though less successful

than hoped, the program did lead to some 600,000 British

immigrants between 1867 and 1890. They continued to

come in large numbers after 1890, more than 1 million

between 1900 and 1914 alone. The percentage of British

immigration declined to 38 percent by 1914, as larger

numbers of southern and eastern Europeans chose to settle

in Canada, but British immigration continued to be the

largest of any country. Between 1946 and 1970, 923,930

Britons settled in Canada and another 311,911 Americans,

many of British descent. After 1970, numbers declined

each decade as non-European immigration took off.

Between 1996 and 2000, immigration from the United

Kingdom ranked 10th as a source country for immigration

to Canada, averaging about 4,600 immigrants per year,

about 2.2 percent of the total, although immigration

dropped steadily from the 1950s. Of almost 632,000

immigrants from the United Kingdom and Ireland (Eire)

in Canada in 2001, 62 percent (392,700) had entered the

country before 1971.

Following the American Civil War (1861–65), the

United States received a steady stream of British immigrants

from both Europe and Canada. Though they constituted

the largest national immigrant group by decade until 1900,

their numbers peaked in three periods: from the mid-1840s

to the mid-1850s, from 1863 to 1873, and from 1879 to

1890. Many were escaping famine in Ireland and economic

hardship elsewhere, but the rapidly industrializing United

States also lured large numbers of skilled workers, machin-

ists, and miners to help drive industrial development. In

1860, more than half of America’s foreign-born population

was British. By the turn of the 20th century, British immi-

gration to the United States was declining, as an increasing

percentage of British immigrants chose to go to Canada,

Australia, or New Zealand. Inexpensive land had become

difficult to find and the specialized skills of British workers

were less needed as industry became more mechanized. This,

in conjunction with Britain’s passage of the Empire Reset-

tlement Act (1922), which assisted migration within the

empire, played a major role in the decline. After World War

II (1939–45), British immigration to the United States

rebounded, aided initially by wartime evacuations and the

entry of 40,000 British war brides, and then by a burgeon-

ing economy. Between 1950 and 1980, about 600,000

British and Irish citizens immigrated to the Unites States;

about 310,000 immigrated between 1981 and 2002. Aver-

age annual immigration to the United States from the

United Kingdom and Ireland (Eire) between 1992 and 2002

was almost 20,000. California became home to more British

immigrants in the 1980s and 1990s than any other state, in

part because of the movie, music, and computer industries

centered there.

See also A

MERICAN

R

EVOLUTION AND IMMIGRATION

;

C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

;

I

RISH IMMIGRATION

; S

COTTISH IMMIGRATION

; U

NITED

S

TATES

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

.

Further Reading

Bailyn, Bernard. The Peopling of British North America: An Introduc-

tion. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1986.

———. Vo

yagers to the West. New York: Knopf, 1986.

Baseler, Marilyn C. “Asylum for Mankind”: America, 1607–1800.

Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1998.

B

er

thoff, Rowland Tappan. British Immigrants in Industrial Amer-

ica: 1790–1950. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press,

1953.

B

umsted, J. M.

The People’s Clearance: Highland Emigration to British

Nor

th America, 1770–1815. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh

Univ

ersity Press, 1982.

Cressy, David. Coming Over: Migration and Communication between

E

ngland and N

ew England in the Seventeenth Century. Cam-

bridge: Cambridge University P

ress, 1987.

Dickson, R. J. Ulster Immigration to the United States. London: Rout-

ledge, 1966.

D

onaldson, G

ordon. The Scots Overseas. London: R. Hale, 1966.

Erikson, Charlotte. The I

nvisible Immigrants: The Adaptation of English

and Scottish Immigr

ants in Nineteenth-Century America. Miami,

Fla.: U

niversity of Miami Press, 1972.

Erikson, Charlotte. Leaving England: Essays on British Emigration in the

N

ineteenth C

entury. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1994.

Fischer

, David Hackett. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in Amer-

ica. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

G

raham, I

an C. C. Colonists from Scotland: Emigration to North Amer-

ica, 1707–1783. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1956.

G

riffin, P

atrick. The People with No Name: Ireland’s Ulster Scots,

America

’s Scots Irish, and the Creation of a British Atlantic World,

1689–1764. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2001.

J

ohnson, S

tanley. A History of Emigration from the United Kingdom to

N

orth America, 1763–1912. London: Routledge and Sons, 1913.

Leyburn, James G. The Scotch-I

rish: A Social History. Chapel Hill: Uni-

versity of N

orth Carolina Press, 1962.

Lines, Kenneth. British and Canadian Immigration to the United States

since 1920. San Francisco: R. and E. Research Associates, 1978.

38 BRITISH IMMIGRATION

Lines, Kenneth. “Britons Abroad.” Economist 325, no. 7791 (1993):

86–88.

Reid, W. Stanford. The Scottish Tradition in Canada. Toronto: McClel-

land and S

te

wart, 1976.

Shepperson, David. British Emigration to North America: Projects and

O

pinions in the E

arly Victorian Period. Oxford: Blackwell, 1957.

Van Vugt, W

illiam E. Britain to America: The Mid-Nineteenth Century

I

mmigrants to the United States. Champaign, Ill.: University of

Illinois P

ress, 1999.

Wilson, David A. United I

rishmen, United States: Immigrant Radicals

in the E

arly Republic. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press,

1998.

W

oods, Lawr

ence M. British Gentlemen in the Wild West: The Era of the

Intensely E

nglish Cowboy. New York: Free Press, 1989.

Bulgarian immigration

There were very few Bulgarian immigrants to North Amer-

ica prior to the 20th century, and they never constituted a

major immigrant group. In the U.S. census of 2000 and the

Canadian census of 2001, only 55,489 Americans identified

themselves as having Bulgarian ancestry, and only 15,195

Canadians. The earlier Bulgarian ethnic neighborhoods

were in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Granite City, Illinois,

while later immigrants congregated in major cities, includ-

ing Detroit, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Toronto

was the first the choice of most Bulgarian Canadians, and

in 2001 more than half lived in Ontario.

Bulgaria occupies 42,600 square miles in the eastern

Balkan Peninsula along the Black Sea between 41 and 44

degrees north latitude. Romania lies to the north; Greece

and Turkey, to the south; and Serbia and Montenegro and

Macedonia, to the west. Several major plains dominate the

landscape. In 2002, the population was estimated at

7,707,495, the majority of which are ethnically Bulgarian. A

minority of Turks lives in Bulgaria and practices Islam, while

most of the country adheres to Bulgarian Orthodox. Slavs

first settled Bulgaria in the sixth century. In the seventh

century Turkic Bulgars arrived, amalgamating with the

Slavs. The nation was Christianized during the ninth cen-

tury. The Ottoman Turks invaded Bulgaria at the end of the

14th century and ruled for more than 400 years. Frequent

revolts led to the exile and forced migration of large num-

ber of Bulgarians to Russia, the Ukraine, Moldavia, Mace-

donia, Hungary, Romania, and Serbia. The first immigrants

who began coming to North America just after the start of

the 20th century were almost all single men who planned

to return to Bulgaria after earning a stake. They worked on

railroads or in other forms of migrant labor, thus not estab-

lishing large ethnic communities. Bulgaria gained territory

during the Aegean War but lost it again as an ally of Ger-

many in World War I (1914–18). In 1944, following its

withdrawal from an alliance with Axis powers in World War

II (1939–45), Bulgaria came under Communist rule, aided

by the Soviet Union. A Communist regime remained in

power until 1991 when a new constitution came into effect.

Despite democratization, the economy went into a sharp

decline that incited national protests in 1997.

It is extremely difficult to establish accurate immigration

figures for Bulgarians. Until the early 20th century, they were

often listed as Turks, Serbs, Greeks, or Macedonians, depend-

ing on the particular passport they were holding. In some

periods, they were grouped with Romanians. Given the esti-

mated numbers of Bulgarian immigrants over a century, one

would expect their numbers to be much larger now. This may

be explained in part by the large return migration during the

Balkan Wars (1912–13) and World War I, in part by the con-

stantly shifting boundaries throughout the region, making

“nationality” a problematic category.

A handful of Bulgarian converts to Protestant Chris-

tianity immigrated to the United States during the last half

of the 19th century, mainly for training, though some chose

to stay. A few hundred Bulgarian farmers settled in Canada

before the turn of the century. The first major wave of Bul-

garian immigration, however, was sparked by the failed Ilin-

den revolt in Turkish Macedonia in 1903. Combined with

the economic distress of native Bulgarians, 50,000 had

immigrated to the United States by 1913 and perhaps

10,000 to Canada. Most Bulgarians were poor, and travel

was difficult from remote regions of southeastern Europe,

so their numbers never approximated those of other Euro-

pean groups. After World War II, a repressive Communist

regime made immigration virtually impossible, sealing the

borders in 1949, though several thousand Bulgarians

escaped and came to the United States as refugees, often

after several years in other countries. Between passage of the

restrictive J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of 1924 and the I

MMI

-

GRATION

A

CT

of 1965, which abolished national quotas,

it is estimated that only 7,660 Bulgarians legally entered the

United States, though some came illegally through Mex-

ico. The restrictive American legislation led more Bulgari-

ans to settle in Canada, with 8,000–10,000 immigrating

during the 1920s and 1930s and several thousand more

between 1945 and 1989.

With the introduction of multiparty politics in 1989,

travel restrictions were eased, leading to a new period of emi-

gration from Bulgaria. Between 1992 and 2002, more than

30,000 Bulgarians immigrated to the United States, most

being skilled workers and professionals. There was a similar

surge of immigration in Canada. Of 9,105 Bulgarian immi-

grants in Canada in 2001, 7,240 (80 percent) came between

1991 and 2001, and 62 percent of these came between 1996

and 2001.

Further Reading

Altankov, Nicolay. The Bulgarian Americans. Palo Alto, Calif.: Ragu-

san Pr

ess, 1979.

Boneva, B. “Ethnic Identities in the Making: The Case of Bulgaria.”

Cultural Survival Quarterly 19, no. 2 (1995): 76–78.

BULGARIAN IMMIGRATION 39

Carlson, C., and D. Allen. The Bulgarian Americans. New York:

Chelsea House, 1990.

Christowe, Stoyan. The Eagle and the Stork: An American Memoir. New

Yor

k: H

arper’s Magazine Press, 1976.

Morawska, Eva. “East Europeans on the Move.” In The Cambridge

S

u

rvey of World Migration. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1996.

P

aprikoff, G. Works of Bulgarian Emigrants: An Annotated Bibliography.

Chicago: G. Paprikoff, 1985.

Petr

off

, L. Sojourners and Settlers: The Macedonian Community in

T

oronto to 1940. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995.

Puskás, J

ulianna, ed. Overseas Migration from East-Central and South-

eastern E

urope, 1880–1940. Budapest: Hungarian Academy of

Science, 1990.

T

rajko

v, V. A History of the Bulgarian Immigration to North America.

S

ofia, Bulgaria: [n.a] 1991.

Bulosan, Carlos (1911–1956) labor activist

Carlos Bulosan, a Filipino migrant worker, emerged as one

of America’s most respected writers and labor activists dur-

ing the 1940s. Although he was disillusioned later in life, his

novels reflect the optimism of immigrant opportunity in the

United States.

Bulosan emigrated from Luzon Island in the Philip-

pines in 1930. Having had considerable contact with

Americans and having heard favorable reports from rela-

tives and friends, he traveled to Seattle, Washington, where

poverty forced him to sell his services to a labor contractor,

who put him to work in the Alaskan canneries. From the

dangerous first season in the canneries through a variety

of low-wage agricultural jobs in Washington, California,

Idaho, Montana, and Oregon, Bulosan learned firsthand

the deceptiveness of the “American dream.” Not only were

jobs hard to find during the depression, but racial preju-

dice was common. Riding boxcars across the West, he wit-

nessed the plight of African Americans, Chinese, Jews, and

fellow Filipinos, who along with poor whites were strug-

gling to make ends meet with dignity. Bulosan nevertheless

met with many acts of kindness by ordinary Americans

and marveled at the moral complexity of the country:

“America is not a land of one race or one class of men,” he

wrote. “We are all Americans that have toiled and suffered

and known oppression and defeat, from the first Indian

that offered peace in Manhattan to the last Filipino pea

pickers.”

Determined to give his people a voice and to help

immigrants cope with their difficulties, Bulosan expressed

his experience in stories and poems. In 1934, he established

the radical magazine The New T

ide and became active in

labor politics. He also published in mainstr

eam magazines

such as the New Yorker and Harper’s Bazaar. In 1950, he

became editor of the highly politiciz

ed y

earbook of the

United Cannery and Packing House Workers of America. At

the time of his death from tuberculosis in 1956, he was lit-

tle known, but Filipino immigrants of the 1960s and 1970s

revived interest in his life and work. Bulosan is best remem-

bered for three semiautobiographical World War II–era

works dealing with the paradox of American attitudes

toward Asian immigrants: The Voice of Bataan (1943), The

Laughter of My Father (1944), and America Is in the Heart

(1946). The 1973 republication of the latter novel led to its

widespr

ead use in college classr

ooms and a greater apprecia-

tion for Bulosan.

See also F

ILIPINO IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Bulosan, Carlos. America Is in the Heart: A Personal History. New York:

Har

court, Brace, 1946.

———. On Becoming Filipino: The Selected Writings of Carlos Bulosan.

Ed. E. San Juan, Jr. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995.

E

vangelista, Susan. Carlos Bulosan and His Poetry: A Biography and

Antholog

y. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila Univer-

sity Pr

ess, 1985.

Lasker, Bruno. Filipino Immigration to Continental United States and

to H

awaii. Chicago: U

niversity of Chicago Press, 1931.

Morantte, P

. C. Remembering Carlos Bulosan. Quezon City, Philip-

pines: Ne

w Day Publishers, 1984.

40 BULOSAN, CARLOS

Filipino agricultural laborers in a lettuce field in the Imperial

Valley, California, 1939. Having come to the United States as a

laborer in 1930, Carlos Bulosan became an important labor

leader in the 1940s. By the 1980s, Filipinos were second only

to the Chinese in overall numbers of Asian immigrants.

(Photo

By Dorothea Lange/Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division

[LC-USF34-019340-E])

Takaki, Ronald. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian

Americans. New York: Penguin, 1990.

Burlingame Treaty

The Burlingame Treaty between the United States and

China (1868) granted “free migration and immigration” to

the Chinese. Although it did not permit naturalization, it

did grant Chinese immigrants most-favored-nation status

regarding rights and exemptions of noncitizens.

Although emigration from China was officially forbid-

den, within four years of the discovery of gold in Califor-

nia, from 1848 to 1852, 25,000 Chinese had immigrated

to California in the hope of striking it rich on “Gold Moun-

tain.” The bloody Taiping Rebellion (1850–64) against the

Qing Dynasty led thousands more to seek asylum abroad.

The Chinese were generally well received.

With the United States embarking on a period of rapid

development of mines, railroads, and a host of associated

industries in the West, Secretary of State William H. Seward

sought a treaty with China that would provide as much

cheap labor as possible. Negotiating for China was a highly

respected former U.S. ambassador to China, Anson

Burlingame, whose principal goal was to moderate Western

aggression in China. In the Burlingame Treaty, signed on

July 28, 1868, the United States agreed to a policy of non-

interference in the development of China. The treaty also

recognized “the inherent and inalienable right of man to

change his home and allegiance” and provided nearly unlim-

ited immigration of male Chinese laborers until the 1882

passage of the C

HINESE

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

.

Further Reading

Biggerstaff, Knight. “The Official Chinese Attitude toward the

Burlingame M

ission.” American Historical Review 41 (July 1936):

682–702.

Hsu, I

mmanuel C.

Y. China’s Entrance into the Family of Nations: The

Diplomatic Phase, 1858–1880. Cambridge, M

ass.: Harvard Uni-

versity P

ress, 1998.

U.S. Congress, Senate. Report of the Joint Special Committee to Investi-

gate Chinese I

mmigr

ation. Report 689. Washington, D.C.:

G.P.O., 1877.

W

illiams, F. W. Anson Burlingame and the First Chinese Mission to

For

eign P

owers. New York: Scribner’s, 1912.

BURLINGAME TREATY 41

Cabot, John (Giovanni Caboto)

(ca. 1450–ca. 1499)

explorer

Giovanni Caboto, one of the ablest seamen of his day, spent

the last years of his life searching for a northwestern route

to the Indies. Sailing under the English flag, he became the

first European since the Vikings (ca. 1000) to set foot on the

North American mainland. He also established English

claims to what would later become Canada and the thirteen

colonies.

The record of both Caboto’s life and voyages is obscure,

as no journals or logs have survived, and the accounts of his

son, Sebastian, are questionable. He was born somewhere

in Italy, becoming a Venetian citizen in 1476. An experi-

enced sailor in the Adriatic, Mediterranean, and Red Seas,

he moved to Spain around 1490, seeking support for a west-

ward voyage. Rejected by both Spain and Portugal, he suc-

cessfully gained the support of Henry VII of England in

1496 and hence became known to history as John Cabot.

On May 20, 1497, he and some 20 seamen set sail from

Bristol in the caravel Matthew and on June 22 sighted the

N

or

th American continent. Landing probably either on

Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island, he claimed the

region for England and returned with reports of rich fishing

grounds. This success ensured a second voyage with the sup-

port of both the king and local merchants. Cabot departed

Bristol with five ships in May 1498. Circumstances sur-

rounding the return of one ship, while Cabot and crews on

the other four perished, remains a mystery. Evidence sug-

gests, however, that he further explored the Newfoundland

fisheries and claimed territories for England along the

Atlantic seaboard as far south as the Carolinas.

Further Reading

Firstbrook, Peter. Voyage of the Matthew. San Francisco: KQED Books

and Tapes,

1997.

Harisse, Henry. John Cabot, the Discoverer of North America, and Sebas-

tian, H

is Son. London: B. F

. Stevens, 1896.

Morison, Samuel E

lliot. The European Discovery of America: The

Nor

thern Voyages,

A

.

D

. 500–1600. New York: Oxford University

Press, 1971.

Williamson, James A. The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery under

H

enr

y VII. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1962.

California gold rush

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in the Sacramento Val-

ley of California in January 1848 enticed thousands of

immigrants from around the world. Between 1848 and the

granting of statehood in 1850 more than 90,000 people

migrated to California, most from within the United States,

but large numbers also from Mexico, Chile, Australia, and

others from many regions of Europe. Almost all arrived

through the port of S

AN

F

RANCISCO

, turning a sleepy vil-

lage into a city of 25,000 in less than two years. Between

1850 and 1852, more than 20,000 people entered Califor-

nia, almost all men. By 1852, the Californian population

had risen to more than 250,000. Among the immigrants

were large numbers of Chinese workers from the impover-

ished and flood-ravaged province of Guangdong (Canton),

42

C

4

who were especially responsive to the attractions of Gam

Saan (Gold Mountain), as California was called in China. In

the early years, 70 percent of Chinese immigrants were min-

ers, though they moved into railroad construction and a

variety of service industries as the placer deposits (those most

easily reached with simple and inexpensive equipment)

played out.

Further Reading

Almaguer, Tomas. Racial Faultlines: The Historical Origins of White

Supremacy in C

alifornia. Berkeley: University of California Press,

1994.

B

rands, H. W. The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New

A

merican Dr

eam. New York: Doubleday, 2002.

Johnson, S

usan Lee. Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California

Gold R

ush. New York: W. W. Norton, 2000.

Liu Pei-chi. A History of the Chinese in the United States of America,

1848–1911. T

aipei, Taiwan: Commission of Overseas Affairs,

1976.

Takaki, R

onald. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian

Americans. New York: Penguin, 1989.

Calvert, Sir George See M

ARYLAND COLONY

.

Cambodian immigration

There was virtually no Cambodian immigration to North

America prior to 1975. As a result of the Vietnam War

(1964–1975) and subsequent regional fighting, large num-

bers of Cambodians were granted refugee status by both the

United States and Canada. In the U.S. census of 2000 and

the Canadian census of 2001, 206,052 Americans and

20,430 Canadians claimed Cambodian descent, though

many working with Cambodians suggest the actual number

is much higher. Almost half of all Cambodians in the United

States live in California, with the largest concentrations in

Long Beach and Stockton. There is also a significant popu-

lation in Lowell, Massachusetts. In Canada, Cambodians

were widely spread following sponsorship opportunities,

though more settled in Montreal than elsewhere.

Cambodia occupies 68,100 square miles of the

Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia between 10 and 15

degrees north latitude. Laos forms part of its northern bor-

der, together with Vietnam, which is also to its east. The

Gulf of Thailand lies to the west. Forests cover most of the

country including the flat areas around Tonle Sap Lake in

the central region and the mountains of the southeast. In

2002, the population was estimated at 12,491,501. The

Khmer ethnic group makes up 90 percent of the population,

which also includes 5 percent Vietnamese and 1 percent

Chinese citizens. Theravada Buddhism is practiced by 95

percent of the people. The Khmer dynasty ruled Cambodia

and much of the Indochina Peninsula between the 9th and

13th centuries. France established a protectorate in the

country in 1863, linking the areas of modern Vietnam,

Laos, and Cambodia in the colonial territory of French

Indochina. France withdrew in 1954, dividing the region

into North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Cambodia was

embroiled in

COLD WAR

conflicts with North and South

Vietnam. When the United States pulled out of Vietnam in

1975, Cambodian Maoist insurgents, organized in a guer-

rilla group known as Khmer Rouge, captured the capital city

of Phnom Penh. Under the leader Pol Pot, most Cambodi-

ans were driven into the countryside and brutally forced to

build up agricultural surpluses. It is estimated that between

1 and 2 million died as a result of execution, starvation, or

disease. In 1979, Vietnam launched a full-scale invasion of

the country over border disputes, toppling the Khmer

CAMBODIAN IMMIGRATION 43

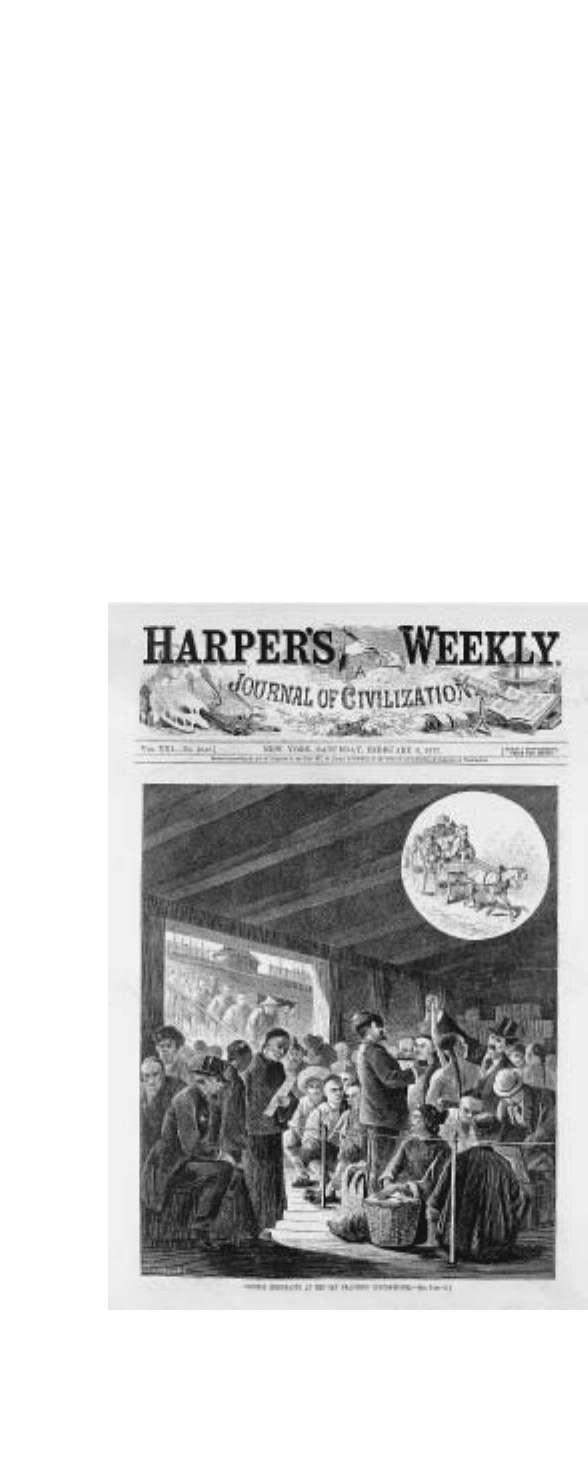

The headline of a Harper’s Weekly in 1877 read “Chinese

immigrants at the San Francisco Custom-House.” A sleepy

Mexican village before the gold rush of 1848, San Francisco

had a population of more than 250,000 by 1852 and quickly

became the center of Chinese immigration.

(Library of

Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-93673])