Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the country. Although most of the methods of gaining ille-

gal entry were well known, fraud was difficult to prove. In

the absence of regular immigration officials—the govern-

ment had no official immigration bureaucracy before

1892—most screening fell to the understaffed customs offi-

cials who were aware of the fraudulent methods used to skirt

the Chinese Exclusion Act and thus came to presume that

the Chinese were inveterate liars and likely criminals. With

the destruction of most immigration records during the

earthquake and resulting fires in San Francisco in 1906,

evading detection became even easier.

With increasing government regulations, it became

impossible to effectively screen immigrants in the two-story

shed at the Pacific Mail Steamship Company wharf in San

Francisco. The Bureau of Immigration (see I

MMIGRATION

AND

N

ATURALIZATION

S

ERVICE

) followed the example of

New York City’s founding of an immigrant station on E

LLIS

I

SLAND

, separated from the city itself. Established in 1910,

the Angel Island detention center on San Francisco’s old

quarantine island included barracks, a hospital, and various

administrative buildings. Here, immigrants could be iso-

lated, both to protect the population from communicable

diseases and to provide time for examination of possible

fraudulent entry claims.

Upon arrival in San Francisco, Europeans and first- and

second-class travelers were usually processed on board and

allowed to disembark directly to the city. All others were fer-

ried to Angel Island where the men and women were sepa-

rated before undergoing stringent medical tests, performed

with little regard for the dignity of the immigrant, looking

particularly for parasitic infections. Afterward, prospective

immigrants were housed in crowded barracks, sleeping in

three-high bunk beds, awaiting interrogation. The grueling

interviews, held before the Board of Special Inquiry, which

included two immigrant inspectors, a stenographer, and a

translator, covered every detail of the background and lives

of proposed entrants. Any deviation from details offered by

family members resulted in rejection and deportation. And

if a successful entrant ever left the country, the transcript of

his or her interrogation was on record for use when he or she

returned. The whole process could take weeks, as family

members on the mainland had to be contacted for corrobo-

rating evidence. In the case of deportation proceedings and

their appeals, an immigrant might spend months or more

than a year on Angel Island. Although this process applied

to all steerage-class passengers, most had fewer obstacles to

surmount than the Chinese did. The Japanese, for instance,

as a result of the G

ENTLEMEN

’

S

A

GREEMENT

(1907), often

had documents prepared by the Japanese government that

shortened the process.

While incarcerated for weeks or months in crowded,

filthy conditions and eating wretched food, many Chinese

immigrants despaired and longed for their homeland. Their

relatives and community officials began to complain of safety

and health concerns. One of hundreds of poems, either writ-

ten on or carved into the wall of the buildings, expressed the

helpless feeling of the unknown author’s situation:

Imprisoned in the wooden building day after day,

My freedom is withheld; how can I bear to talk about

it?

I look to see who is happy but they only sit quietly.

I am anxious and depressed and cannot fall asleep.

The Days are long and bottle constantly empty;

My sad mood even so is not dispelled.

Nights are long and the pillow cold; who can pity my

loneliness?

After experiencing such loneliness and sorrow,

Why not just return home and learn to plow the

fields?*

It was a fire, however, rather than government action, that

finally shut down the Angel Island facility. The administra-

tion building burned to the ground in April 1940, and by

the end of the year, all detainees had been moved to the

mainland. Three years later in the midst of World War II,

the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed, thus allowing Chi-

nese immigrants to become naturalized citizens.

The old site of the detention center was briefly used as

a prisoner-of-war processing center during World War II,

before falling into decay. In 1963, it was incorporated into

the Angel Island State Park, and 13 years later, the Califor-

nia state legislature appropriated $250,000 to restore the

barracks, which were opened to the public as a museum in

1983. Also in that year, the Angel Island Immigration Sta-

tion Foundation was created to partner with the California

State Parks and the National Park Service to continue pro-

grams of restoration and education. In 1997, the site was

declared a National Historic Landmark.

Further Reading

Chen, Helen. “Chinese Immigration into the United States: An Anal-

ysis of Changes in Im

migration Policies.” Ph.D. diss., Brandeis

University, 1980.

Daniels, Roger. “No Lamps Were Lit for Them: Angel Island and the

Historiography of Asian American Immigration.” Journal of

American E

thnic History 17 (Fall 1997): 3–18.

Lai, Him Mark. Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities

and Institutions. Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira Press, 2004.

Lai, H

im Mark, Genny Lim, and Judy Yung, eds. Island: Poetry and

History of Chinese I

mmigrants on Angel Island, 1910–1940. Seat-

tle: Univ

ersity of Washington, 1991.

Lee, Erika. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration During the Exclu-

sion Er

a, 1882–1943. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina

Pr

ess, 2003.

14 ANGEL ISLAND

*From Him Mark Lai, Genny Lim, and Judy Yung, eds. Island: Poetry

and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910–1940 (Seattle:

Univ

ersity of Washington, 1991), p. 68.

McGinty, Brian. “Angel Island: The Door Half Closed.” American

History Illustrated (September–October 1990): 50–51, 71.

Naka, M

ary. “Angel Island Immigration Station.” Survey of Race Rela-

tions (1922). Stanfor

d, Calif.: Stanford University, Hoover Insti-

tution Ar

chives, 1922.

Stolarik, M. Mark, ed. Forgotten Doors: The Other Ports of Entry into

the U

nited S

tates. Philadelphia: Balch I

nstitute Press, 1988.

Takaki, Ronald. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian

Americans. N

ew York: Penguin Books, 1989.

Wong, Esther. “

The History and Problem of Angel Island.” Survey of

R

ace Relations (March, 1924). Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Univer-

sity, H

oover Institution Archives.

Anti-Defamation League

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), a branch of the Jew-

ish service organization B’

NAI

B’

RITH

, is committed to

fighting racial prejudice and bigotry. Through an extensive

program of publication, public speaking, and lobbying, it

has developed considerable political influence. Concerned

especially with First Amendment issues, the ADL has been

especially active in monitoring the activities of hate groups

and militias.

A series of pogroms in Russia (1903–06) led Ameri-

canized German Jews to form the American Jewish Com-

mittee (1906), dedicated to protecting Jewish civil rights

around the world. The concept was directly tested in the

United States itself in 1913 when Leo Frank, a Jewish fac-

tory superintendent, was convicted of an Atlanta, Georgia,

murder, kidnapped from prison, and lynched. He was later

exonerated of the crime. Within a month, midwestern Jews

founded the ADL in order to counter racially based claims

emanating from the controversy. The ADL played an espe-

cially large cultural role from the time of its founding until

the end of World War II, a period when overt anti-Semitism

was common in the United States.

Further Reading

Dinnerstein, Leonard. Antisemitism in America. New York: Oxford

Univ

ersity Press, 1994.

Sorin, Gerald. A T

ime for Building: The Third Migration, 1880–1920.

B

altimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

So

yer, Daniel. Jewish Immigrant Associations and American Identity in

New Y

ork, 1880–1939. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University

Pr

ess, 1997.

Antin, Mary (1881–1949) author

Mary Antin was a powerful voice for immigrant assimilation

in America and one of the foremost champions of an open

immigration policy in the early 20th century.

Born in Polotsk, Russia, she, her mother and her sib-

lings joined her father, who had emigrated in 1891, in Mas-

sachusetts in 1894. Her first book, From Plotzk to Boston

(1899), was written in Yiddish. She became nationally

famous with her autobiographical The Promised Land

(1912), which had been serialized in the Atlantic Monthly.

Following the success of The Promised Land, she lectured

widely and fr

equently spoke on behalf of

Theodore Roo-

sevelt and the Progressive Party. Antin’s ardent support for

immigrant conformity to Anglo societal norms made her

popular with mainstream audiences and led to widespread

use of her works in public schools.

Further Reading

Guttmann, Allen. The Jewish Writer in America: Assimilation and the

Crisis of Identity

. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

P

roefriedt, William A. “The Education of Mary Antin.” Journal of

Ethnic S

tudies 17 (1990): 81–100.

Tuer

k, Richard. “At Home in the Land of Columbus: Americanization

in European-American Immigrant Autobiography.” In Multicul-

tural A

utobiogr

aphy: American Lives. Ed. James Robert Payne.

Kno

xville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992.

Arab immigration

The majority of Arabs in North America are the largely

assimilated descendants of Christians who emigrated from

the Syrian and Lebanese areas of the Ottoman Empire

between 1875 and 1920. A second wave of immigration

after 1940 was more diverse and more heavily Muslim,

including substantial numbers from Egypt, Iraq, Jordan,

Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Syria, and Yemen. In the U.S.

census of 2000 and the Canadian census of 2001 1,202,871

Americans and 334,805 Canadians claimed Arab ancestry or

descent from peoples of predominantly Arab countries.

Some analysts estimate the U.S. figure at closer to 3 mil-

lion. As late as 1980, about 90 percent were Christians,

though the majority of immigrants since 1940 have been

Muslims. The greatest concentration of Arabs in the United

States is in the greater Detroit, Michigan, area, particularly

Dearborn, with a population estimated at more than

200,000. Los Angeles County, California; Brooklyn, New

York; and Cook County, Illinois, also have large Arab pop-

ulations. Montreal, Quebec, has by far the largest Arab pop-

ulation in Canada.

Arab is a general ethnic term to designate the peoples

who originated in the Arabian P

eninsula. I

n modern times,

it more generally applies to those who speak Arabic and

embrace Arab culture. Arabs form the majority populations

in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Yemen, Oman, the United Arab

Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan,

Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. Sudan is about

50 percent Arab. Some Arabs migrated northward into the

Tigris and Euphrates river valleys about 5,000 years ago,

mixing with various Persian and Indo-European peoples to

form a common Mesopotamian culture. Arab culture was

widely spread only with the advent of the expansionistic

Islamic faith. In the 120 years following the Prophet

ARAB IMMIGRATION 15

Muhammad’s death in 632, Arab leaders conquered the

entire region stretching from modern Pakistan to Spain.

This resulted in the spread of both Islam and the broader

Arab culture. In some regions, Islam was embraced within

the context of deeply rooted, non-Arabic culture patterns.

This was the case most notably in Pakistan, Afghanistan,

Iran (ancient Persia), and Turkey. From the late 16th cen-

tury, most Arab lands were controlled or influenced by the

Turkish Ottoman Empire. Though Turkish influence waned

in the 18th and 19th centuries, leading to greater European

influence in northern Africa and the coastal regions of

southwest Asia, the Ottoman Empire continued to control

Kuwait, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, and much

of the Arabian Peninsula until the end of World War I

(1918).

The term Arab has been used in so many different ways

that exact immigration figures ar

e difficult to arriv

e at.

When the number of people arriving in North America

from the region of North Africa/Southwest Asia was small,

immigrants from the Ottoman Empire were usually classi-

fied in the category “Turkey in Asia,” whether Arab, Turk, or

Armenian. By 1899, U.S. immigration records began to

make some distinctions, and by 1920, the category “Syrian”

was introduced into the census, though religious distinctions

still were not noticed. Throughout the 20th century, there

was little consistency in designation, principally because

overall numbers remained small. As a result, Arabs might

variously have been listed according to country, as “other

Asian” or “other African,” or as nationals of their last coun-

try of residence.

The first major movement of Arabs to North America

came from Lebanon in the late 19th century. At the time,

Lebanon was considered a region within the larger area of

Syria, so the term Syrian was most often used. As “Syrian”

Christians living in an I

slamic empir

e, Lebanese Arabs were

subject to persecution, though in good times they were

afforded considerable autonomy. During periods of drought

or economic decline, however, they frequently chose to emi-

grate. Between 1900 and 1914, about 6,000 immigrated to

the United States annually. Often within one or two gener-

ations these Lebanese immigrants had moved into the mid-

dle class and largely assimilated themselves to American life.

Although Syrians began migrating to Canada about the

same time, their numbers were much smaller. As late as

1961, the population was less than 20,000. Though mostly

Christians, they were divided into several branches, includ-

ing Maronites, Eastern Orthodox, and Melkites. The next

wave of Arabs to immigrate to North America, most in the

wake of the Arab-Israeli War of 1967, were overwhelmingly

Muslim and had little in common with those who had

arrived early in the century.

See also E

GYPTIAN IMMIGRATION

;I

RAQI IMMIGRA

-

TION

;L

EBANESE IMMIGRATION

;M

OROCCAN IMMIGRA

-

TION

;P

ALESTINIAN IMMIGRATION

;S

YRIAN IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Booshada, Elizabeth. Arab-American Faces and Voices: The Origins of an

I

mmigrant Community. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003.

Elkholy

, Abdo. The Arab Moslems in the United States: Religion and

Assimilation. Ne

w Haven, Conn.: College and University Press,

1966.

Kashmeri, Z

uhair. The Gulf Within: Canadian Arabs, Racism, and the

Gulf W

ar

. Toronto: J. Lorimer, 1991.

K

oszegi, Michael A., and J. Gordon Melton, eds. Islam in North Amer-

ica: A Sourcebook. N

ew York: Garland Publishing, 1992.

McCarus, E

rnest, ed. The Development of Arab-American Identity. A

nn

Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Naff, Alixa. Becoming American: The Early Arab American Experience.

Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985.

O

rfalea, Gregory. Before the Flames: A Quest for the History of Arab

Americans. Austin: U

niversity of Texas Press, 1988.

S

uleiman, Michael W., ed. Arabs in America: Building a New Future.

Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000.

Z

o

gby, John. Arab America Today: A Demographic Profile of Arab Amer-

icans. Washington, D.C.: Arab American Institute, 1990.

Argentinean immigration

Argentineans first arrived in the United States and Canada

in significant numbers during the 1960s, primarily seeking

economic opportunities. In the 2000 U.S. census, 100,864

Americans claimed Argentinean descent, compared to 9,095

Canadians in their 2001 census. Most Argentinean immi-

grants, many of Italian origin, settled in large metropolitan

areas, with New York and Los Angeles being most popular.

More than half of Argentinean Canadians live in Ontario,

with most having settled in Toronto.

Argentina occupies 1,055,400 square miles of southern

South America between 21 and 55 degrees south latitude.

Bolivia and Paraguay lie to the north and Brazil, Uruguay,

and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. The Andes Mountains

stretch north to south along Argentina’s western border with

Chile. East of the mountains lie heavily wooded areas

known in the north as the Gran Chaco. The Pampas, an area

of extensive grassy plains, cover the central region of the

country. In 2002, the population was estimated at

37,384,816, with more than 12 million in the urban vicin-

ity of Buenos Aires. The majority practice Roman Catholi-

cism. Beginning in the early 16th century, Spanish colonists

migrated to Argentina, driving out the indigenous popula-

tion. In 1816, colonists gained independence, and by the

late 19th century Argentina was competing with the United

States, Canada, and Australia for European immigrants. By

1914, 43 percent of Argentina’s population was foreign

born, with most coming from Spain, Italy, and Germany.

Military coups slowed modernization from 1930 until

1946 when General Juan Perón was elected president. Perón

ruled until 1955, when he was exiled by a military coup.

Military and civilian governments followed until Perón’s

reelection in 1973. In 1976, a military coup ousted Perón’s

16 ARGENTINEAN IMMIGRATION

wife, Isabel, who had assumed the presidency following her

husband’s death in 1974. During the Dirty War (1976–83),

approximately 30,000 opponents of the right-wing regimes

that succeeded Perón were tortured and killed, leading to

increased international interest in Argentine refugees. In

1978, the United States launched the Hemispheric 500 Pro-

gram, providing parole for several thousand Chilean and

Argentinean political prisoners. In the following year,

Canada created a new refugee category for Latin American

Political Prisoners and Oppressed Persons. In both cases, the

standards for entry were higher than for refugees from

Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe, where applicants were

fleeing from communist regimes, leading critics to argue

that immigration policy was being driven by

COLD WAR

concerns.

As the military’s hold on power weakened, Argentina

invaded the British-held Falkland Islands in April 1982 but

surrendered them less than three months later. The national

economy thereafter faced prolonged recession, leading many

professionals to continue to seek employment in the United

States and Canada. Argentines are economically better off

than most Hispanic immigrant groups and less likely to live

in communities defined by ethnicity.

Prior to 1960, the U.S. Census Bureau did not separate

Hispanic nationalities, so it is difficult to determine exactly

how many Argentineans had entered the United States

before that time. By the 1970 census, however, there were

44,803 living in the United States, most of whom were well-

educated professionals. A second wave of immigration began

in the mid-1970s, with refugees fleeing the Dirty War of the

right-wing military regime. By 1990, almost 80 percent of

Argentinean Americans had been born abroad. Between

1992 and 2002, Argentinean immigration averaged about

2,500 annually.

A very limited Argentinean immigration to Canada

began early in the 20th century, the most notable being a

small community of about 300 Welsh Argentines who relo-

cated to Saskatchewan. Between passage of the I

MMIGRA

-

TION

A

CT

of 1952 and the early 1970s, Argentinean

immigration averaged several hundred per year, driven both

by Argentina’s economic decline and by Canada’s new pro-

visions for highly trained immigrants. Between 1973 and

1983, rapid inflation and government oppression during the

Dirty War led an average of more than 1,000 Argentineans

to relocate to Canada. Of 13,830 Argentinean immigrants

in Canada in 2001, 3,180 arrived between 1971 and 1980,

2,790 between 1981 and 1990, and 4,200 between 1991

and 2001.

Further Reading

Barón, A., M. del Carril, and A. Gómez. Why They Left: Testimonies

from A

rgentines Abroad. Buenos Aires: EMECE, 1995.

Lattes, Alfredo E., and E

nrique Oteiza, eds. The Dynamics of Argentine

Migr

ation, 1955–1984: Democracy and the Return of Expatriates.

Trans. David Lehmann and Alison Roberts. Geneva: United

N

ations and Research Institute for Social Development, 1987.

Marshall, A. The Argentine Migration. Buenos Aires: Flasco, 1985.

Pinal, J

orge del, and A

udrey Singer. “Generations of Diversity: Latinos

in the United States.” Population Reference Bureau Bulletin 52,

no

. 3 (1997): 1–44.

Rockett, I

an R. H. “Immigration Legislation and the Flow of Special-

ized Human Capital from South America to the United States.”

International Migration Review 10 (1976): 47–61.

Armenian immigration

Armenians first migrated to North America in large num-

bers following the massacres of 1894–95 at the hands of the

Ottoman Empire. An attempted genocide during World

War I (1914–18) led to another influx. Finally, the rise of

Arab nationalism during the 1950s led to the emigration of

tens of thousands of Armenians from Islamic countries

throughout the Middle East. In the U.S. census of 2000 and

the Canadian census of 2001, 385,488 Americans claimed

Armenian descent, while 40,505 did so in Canada. The early

centers of Armenian settlement in the United States were

New York City, Boston, and Fresno, California. Since 1970,

the majority of Armenians settled in the Los Angeles area,

making it the largest Armenian city outside their home-

land, with a population of more than 200,000. Brantford,

Ontario, was the largest Canadian settlement of Armenians

prior to World War II (1939–45), though by 2000, almost

half lived in Montreal and about one-third in Toronto.

The modern state of Armenia that emerged from the

breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 occupies 11,500

square miles of Southwest Asia between 38 and 42 degrees

north latitude. The ancient kingdom was almost 10 times

larger. Georgia lies to the north of modern Armenia; Azer-

baijan, to the east; Iran, to the south; and Turkey, to the

west. The land is mostly mountainous. In 2002, the popu-

lation was estimated at 3,336,100, with over a third in the

urban area of the capital city Yerevan. Ninety-three percent

of the population is ethnically Armenian. Minority ethnic

groups include Azeri, Russian, and Kurd. Armenian Ortho-

dox is the principal religion of the country.

Armenians are an ancient people who have inhabited

the Caucasus mountain area and eastern Anatolia (modern

Turkey) for more than 2,500 years. Although various Arme-

nian states exercised sovereignty in the ancient and medieval

periods, the region was most often dominated by more pow-

erful neighbors, including Persia, Rome, the Seljuk Turks,

and the Ottoman Turks. As Christians, Armenians were sub-

ject to frequent persecution at the hands of Islamic govern-

ments. In the 1890s, an Ottoman attempt to rid the empire

of this troublesome minority led to the murder of several

hundred thousand Armenians and an international call for

reforms. After Ottoman defeat in World War I, Armenia

briefly declared a republic (1918). Fearing Turkish aggres-

ARMENIAN IMMIGRATION 17

sion, the country accepted the protection of the Soviets in

1920 and in 1922 joined with Georgia and Azerbaijan to

form the Transcaucasian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic

within the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). In

1936, Armenia became an independent constituent repub-

lic of the USSR. In 1988, nearly 55,000 Armenians were

killed in an earthquake that destroyed several cities. Since

independence, in 1991, fighting between Armenia and

largely Muslim Azerbaijan over the Armenian enclave of

Nagorno-Karabakh has kept political tensions high in the

country.

Despite the fact that an Armenian farmer immigrated

to Virginia as early as 1618, it is estimated that there were

fewer than 70 Armenians in the United States prior to 1870.

The first great migration came in the wake of the massacres

of 1894–95. During the remainder of that decade, perhaps

100,000 Armenians immigrated to the United States. After

the Turkish government killed more than a million Armeni-

ans during World War I, another 30,000 escaped to Amer-

ica before the restrictive J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

(1924)

effectively closed the door, reducing the annual quota to

150. Following World War II, the D

ISPLACED

P

ERSONS

A

CT

(1948) enabled some 4,500 Armenians to come to the

United States outside the quota. Finally, tens of thousands of

Armenians who had been driven by Turkey into Iran, Iraq,

Lebanon, Egypt, Palestine, and Syria following World War

II immigrated during the 1950s. It is difficult to determine

with precision the number of Armenians who have come to

North America, because they emigrated from many Middle

Eastern countries and often were counted on the basis of

their immediately previous country of residence. Between

1960 and 1984, about 30,000 Armenians fled the USSR,

most settling in the greater Los Angeles area. As Soviet con-

trol of its republics began to weaken in the late 1980s, thou-

sands more immigrated to the United States. It has been

estimated that more than 60,000 came during the 1980s.

Following the initial turmoil surrounding Armenian inde-

pendence in 1991, numbers gradually declined. Between

1994 and 2002, Armenian immigration to the United States

averaged about 2,000 annually. This figure does not include

Armenians from Turkey or Iran.

During the 1890s, a small number of Armenians settled

on the western prairies of Canada, but a substantial com-

munity failed to develop. Around the turn of the century, a

larger contingent of mainly entrepreneurs and factory work-

ers settled in southern Ontario. By 1914 there were about

2,000 Armenians in Canada. Restrictions classifying Arme-

nians as “Asiatics” effectively stopped immigration until the

1950s, though about 1,300 were admitted as refugees dur-

ing the 1920s. Many were orphans sponsored by religious or

charitable organizations. With the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of

1952, Armenians were no longer classified as Asiatics and

thus found immigration easier. The Canadian Armenian

Congress sponsored hundreds of Armenian immigrants in

the 1950s and 1960s, with most settling near their head-

quarters in Montreal. Only about 4 percent of Armenian

Canadians immigrated after 1961, with 1,130 coming

between 1991 and 2001.

Further Reading

Armenians in America—Celebrating the First Century on the Occasion of

the N

ational Tribute for Governor George Deukmejian, October 10,

1987. Washington, D.C.: Armenian Assembly of America, 1987.

Av

akian, A. S. T

he Armenians in America. Minneapolis, Minn.: Lerner

,

1977.

Bakalian, Anny. Armenian-Americans: From Being to Feeling Armenian.

New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction, 1993.

Bournoutian, A. G. A H

istory of the Armenian People. 2 vols. Costa

M

esa, Calif.: Mazda, 1993–94.

Chichekian, Garo. The Armenian Community of Quebec. Montreal:

G. Chichekian, 1989.

D

eranian, H

agop Martin. Worcester Is America: The Story of Worcester’s

Ar

menians, the Early Years. Worcester, Mass.: Bennate Publica-

tions, 1998.

K

ulhanjian, G

ary A. The Historical and Sociological Aspects of Arme-

nian Immigr

ation to the United States, 1890–1930. San Francisco:

R. and E. Resear

ch Associates, 1975.

Malcolm, M. Vartan. Armenians in America. Boston and Chicago:

P

ilgrim

’s Press, 1919.

Mirak, Robert. Torn between Two Lands: Armenians in America 1890

to W

or

ld War I. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press,

1983.

T

akooshian, H

arold. “Armenian Immigration to the United States

Today from the Middle East.” Journal of Armenian Studies 3

(1987): 133–155.

Tashijian, James H. The Armenians of the United States and Canada: A

Brief Study. Boston: Armenian Youth Federation, 1970.

V

assilian, Hamo B., ed. Armenian American Almanac. 3d ed. Glendale,

Calif.: Armenian Refer

ence Books, 1995.

Waldstreicher, D. The Armenian Americans. New York: Chelsea

H

ouse, 1989.

W

ertsman, Vladimir. The Armenians in America, 1616–1976: A

Chr

onolog

y and Fact Book. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana Publica-

tions, 1978.

Australian immigration

As a traditional country of reception for immigrants, large

numbers of Australians never immigrated to North America.

In the U.S. census of 2000 and the Canadian census of

2001, 78,673 Americans claimed Australian descent, com-

pared to 25,415 Canadians. Unofficial estimates place the

number much higher. As many of these immigrants had

either previously immigrated to Australia from somewhere

else or were the descendants of immigrants, it is suspected

that census data often reflects country of earliest ancestry

rather than country of last residence. Australians are spread

throughout the United States, with the largest concentration

in southern California. They blend easily into mainstream

18 AUSTRALIAN IMMIGRATION

American and Canadian cultures and do not readily join

ethnic groups.

Australia, the only country occupying an entire conti-

nent, covers 2,966,150 square miles, almost as large as the

lower 48 states of the United States. Like the North Ameri-

can continent, Australia was lightly populated by native peo-

ples, the Aborigines, when Europeans arrived in the late

18th century. Unlike the United States and Canada, its great

distance from Europe and restrictive immigration policies

limited population growth. In 2002, Australia’s population

was just under 20 million, with 92 percent being of Euro-

pean descent, 6.4 percent of Asian descent, and 1.5 percent

of Aboriginal descent.

The Dutch explored Australia in the early 17th century

but did not colonize it. Captain James Cook’s explorations

between 1769 and 1777 led to an English settlement in New

South Wales, dominated by convicts, soldiers, and officials.

After the American Revolution, with the thirteen colonies

no longer available for convict transportation, the British

government began to exile convicts to Australia, a policy

that led to the forced immigration of 160,000 men, women,

and children between 1788 and 1868. By 1830, Great

Britain claimed the entire island. In 1901, Australia became

a commonwealth and immediately barred almost all “col-

oreds” from entry. Australia became fully independent of

Great Britain in 1937. Since 1973, Australia’s immigration

policy has been nonracial. About one-third of immigrants in

2000 were Asian.

Australians usually immigrated to North America in pur-

suit of economic opportunity, beginning with more than

1,000 during the first years after the C

ALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH

(1848). In 1851, however, most returned when gold was dis-

covered in western Australia. During the 19th century, immi-

gration to the United States averaged less than 1,000 per year.

World War II (1939–45) led to a significant rise in immigra-

tion, boosted by 15,000 Australian war brides returning with

American soldiers who had been stationed there. Between

1960 and 2000, Australian immigration rose as economic

conditions at home worsened and fell as they improved, with

the annual average at about 4,000. Throughout the 19th and

early 20th centuries, there was little immigration from Aus-

tralia to Canada, in part because of unwritten agreements to

avoid competition for immigrants. Data for Australian immi-

gration to Canada are unreliable, but there were only 2,800

Australian-born Canadians in 1941. Immigration began to

grow during the 1950s, as working conditions for nurses, aca-

demics, and other professionals were similar in both countries,

but pay was generally better in Canada. It peaked in 1967,

with almost 5,000 Australians entering. As was true through-

out the 20th century, however, many came for education or

temporary jobs and frequently returned to their homeland. As

a result of the 1976 I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

, which made it more

difficult to be admitted for work if Canadians could be found

to do the job, immigration dropped significantly. Of the

16,030 Australian Canadians in 2001, about 6,400 came after

1980.

Further Reading

Bateson, Charles. Gold Fleet for California: Forty-Niners from Aus-

tralia and N

ew Zealand. East Lansing: Michigan State Univer-

sity Pr

ess, 1963.

Cuddy, Dennis Laurence. “Australian Immigration to the United

States: From Under the Southern Cross to ‘The Great Experi-

ment.’” In Contempor

ary American Immigration: Interpretive

E

ssays. Ed. Dennis Laurence Cuddy. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1982.

Mo

ore, J. H., ed. Australians in America, 1876–1976. Brisbane, Aus-

tralia: Univ

ersity of Queensland Press, 1977.

Austrian immigration

In the U.S. census of 2000 and the Canadian census of

2001, 735,128 Americans and 147,585 Canadians claimed

Austrian ancestry. Because German speakers were divided

among several states during the great European age of immi-

gration (1820–1920), yet almost always embarked for the

New World from German ports, it is difficult to determine

exactly how many immigrants came from various states of

the old German Confederation (to the 1860s); from the

German Empire (from 1870); or from Austria and the Sude-

ten regions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Between 1861

and 1910, the U.S. Bureau of Immigration drew no dis-

tinctions among more than a dozen ethnic groups emigrat-

ing from the empire (see A

USTRO

-H

UNGARIAN

IMMIGRATION

). After 1919, Austrian immigration corre-

sponds to the successor state of Austria, one of six created

from the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire follow-

ing World War I. Austrian immigrants, many of whom were

Jewish, tended to settle in New York, Chicago, and other

large cities during the 19th and early 20th centuries. New

York City remains the center of Austrian settlement in the

United States, though there are growing concentrations in

California and Florida. Although Austrians tended to settle

on the Canadian prairies during the first half of the 20th

century, by the end of the century, the greatest concentra-

tion was in Toronto, with significant pockets of settlement

in other cities of Ontario. In both the United States and

Canada, Austrians assimilated rapidly and were not inclined

to join purely Austrian groups.

Austria is a mountainous, landlocked country of 31,900

square miles, lying between 46 and 49 degrees north lati-

tude. It is surrounded by Switzerland and Liechtenstein on

the west; Germany and the Czech Republic on the north,

Slovakia and Hungary on the east, and Italy and Slovenia on

the south. Its population of 8,150,835 is 99 percent ethnic

German, 78 percent of whom are Roman Catholic. From

the Middle Ages, Austria formed the core of a large multi-

ethnic empire that was finally broken apart following defeat

in World War I.

AUSTRIAN IMMIGRATION 19

After the war, the economic situation was unsettled in

the old German-speaking center of the empire, leading

18,000 Austrians to immigrate to the United States between

1919 and 1924. With the imposition of restrictive quotas

in the J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

(1924), Austrian immigration

was first limited to 785 per year, though it was revised

upward to 1,413 in 1929. Eventually another 16,000 immi-

grated between 1924 and 1937. As a result of American

restrictions, Austrian immigration to Canada, Argentina,

and Brazil increased, with more than 5,000 settling in

Canada during the interwar years. With mounting pressure

on European Jews in the 1930s, Jewish Austrians of means

increasingly sought opportunities to leave. President

Franklin Roosevelt relaxed restrictions on refugee immi-

grants in 1937, leading to an increase in visas. Between the

incorporation of Austria into the German Reich in 1938

and the entry of the United States into World War II in

1941, 29,000 Austrian Jews entered the United States, most

of whom were well educated, and many of whom were inter-

nationally renowned in their various fields of study (see

W

ORLD

W

AR

II

AND IMMIGRATION

). In the first two

decades following World War II, more than 100,000 Austri-

ans immigrated to the United States, the numbers boosted

by the allocation of nonquota visas for refugees and their

families during the 1950s. Immigration declined and return

migration quickened, however, as Austria established a

strong economy and effective social service system by the

mid-1960s. Between 1992 and 2002, average annual immi-

gration was just under 500.

Most immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire

to Canada were not from the present-day country of Austria.

Of perhaps 200,000 immigrants prior to World War I, most

were Slavic; probably fewer than 10,000 were German

speakers from the modern region of Austria. A large number

came from the province of Burgenland. Prior to World War

I, most of these settled on the prairies of Saskatchewan,

where they were joined by small numbers of Burgenlanders

from the United States. Following World War I, they were

designated “nonpreferred” because of their association with

the defeated Central Powers. As a result, during the 1920s

and 1930s, about 5,000 Austrians immigrated to Canada,

with most settling in the western provinces, around 70 per-

cent in Manitoba alone. After World War II, Austria faced a

long and difficult rebuilding process that prompted many

Austrians to immigrate to Canada, with the majority settling

in Ontario. Of the 22,130 Austrian immigrants in Canada

in 2001, about 62 percent (13,645) arrived prior to 1961.

Further Reading

Engelmann, Frederick, Manfred Prokop, and Franz Szabo, eds. A His-

tory

of the Austrian Migration to Canada. Ottawa: Carleton Uni-

versity Press, 1996.

G

oldner

, Franz. Austrian Emigration, 1938–1945. Trans. Edith

Simons. New Yor

k: F. Ungar, 1979.

Pick, Hella. Guilty

Victim: Austria from the Holocaust to Haider. New

Yor

k: I. B. Tauris, 2000.

Schlag, Wilhelm. “A Survey of Austrian Emigration to the United

States.” In Österr

eich und die angelsächsische Welt. Ed. Otto von

Hietsch. Vienna, Austria, and Stuttgart, Germany: W.

Braumüller, 1961.

Spaulding, E. Wilder. The Q

uiet Invaders: The Story of the Austrian

I

mpact upon America. Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag,

1968.

Stadler

, F

., and P. Weibl, eds. Cultural Exodus from Austria. 2d rev. ed.

V

ienna: Springer Verlag, 1995.

Szabo, F., F. Engelmann, and M. Prokop, eds. Austrian Immigration to

C

anada: S

elected Essays. Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1996.

Austro-Hungarian immigration

Austria-Hungary was a large, landlocked dynastic state situated

in central and southeastern Europe; it was partitioned follow-

ing World War I (1914–1918). In the great wave of European

migration between 1880 and 1919, Italy and Austria-Hungary

each sent more than 4 million immigrants to the United States,

totaling more than one-third of the 24 million total immi-

grants from that period. Migration to Canada was severely

restricted by German travel requirements—from whose ports

almost all Austrians traveled—which made migration to the

United States vastly easier. Some 200,000 Austro-Hungarians

nevertheless eventually made their way to Canada between

1880 and 1914, with the vast majority being Slavs.

Austria-Hungary was a vast, multinational empire that

lagged far behind western European countries in both eco-

nomic development and individual freedom, thus providing

impetus for the empire’s Poles, Czechs, Jews, Magyars (Hun-

garians), Slovenes, Croatians, Slovaks, Romanians, Rutheni-

ans, Gypsies, and Serbs to seek new opportunities in North

America. The exact number of immigrants from the Aus-

tro-Hungarian Empire cannot be determined, nor can the

numbers within particular ethnic groups. Not only were

official records not kept in Austria-Hungary during most of

the period, the nomenclature used to classify immigrants

frequently changed. Also, members of various central and

eastern European ethnic groups arriving in the United States

or Canada were often mistaken for one another.

In the 18th century, what would become Austria-Hun-

gary was usually referred to by its dynastic name, the Habs-

burg Empire, and increasingly in the 19th century as the

Austrian Empire. Thus, all subjects of the Habsburg crown

were properly referred to as “Austrians.” With the rise in

nationalistic sentiment from the early 19th century, more

Austrians began to identify themselves according to their

native culture and language. This growing sense of nation-

alism led to a number of revolutions in 1848 and eventually

in 1867 to the creation of a new federal system of govern-

ment in which Hungarian Austrians were given legislative

equality with German Austrians. Both partners discrimi-

nated against other ethnic groups, particularly the Slavs.

20 AUSTRO-HUNGARIAN IMMIGRATION

Only a handful of Austrians immigrated to North

America prior to the mid-19th century. When the Catholic

bishop-prince of Salzburg exiled 30,000 Protestants from his

lands in 1728, several hundred settled in Georgia. A few rad-

ical reformers fleeing the failed revolutions of 1848 settled in

the United States as political refugees. Most were middle

class and reasonably well educated and tended to cluster in

New York City and St. Louis, Missouri, where there were

already large German-speaking settlements. Although the

official estimate that fewer than 1,000 Austrians were in

America in 1850 is almost certainly wrong, it does suggest

the limited migration that had taken place by that time.

By the 1870s, however, several factors led to a rapid

increase in immigration. The emancipation of the peasantry

beginning in 1848 led to the creation of a market economy

and the potential for wage earnings and individual choices

about migration. Overpopulation also contributed to the

rapid increase in immigration. With a rapidly growing pop-

ulation, laws and inheritance patterns reduced the majority

of farms to tiny plots that could barely support a family. As

more agricultural workers were uprooted from the land, it

became more common for them to try their hand in North

America when prospects in Austrian cities failed. Finally, a

heightened sense of nationalism encouraged Austro-Hun-

garian minorities to escape the discriminatory policies of the

Austrians and Hungarians.

From 1870 to 1910, immigration increased dramati-

cally each decade, despite restrictions on immigration pro-

paganda. Many ethnic groups, including Poles, had high

rates of return migration, suggesting immigration as a tem-

porary economic expedient. On the other hand, German

Austrians, Jews, and Czechs tended to immigrate as families

and to establish permanent residence. With the United

States and Austria-Hungary on opposite sides during World

War I (1914–18), immigration virtually ceased. More than

100,000 Canadians of Austro-Hungarian origin were

declared enemy aliens. At the end of the war, the anachronis-

tic, multiethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire was dismembered

AUSTRO-HUNGARIAN IMMIGRATION 21

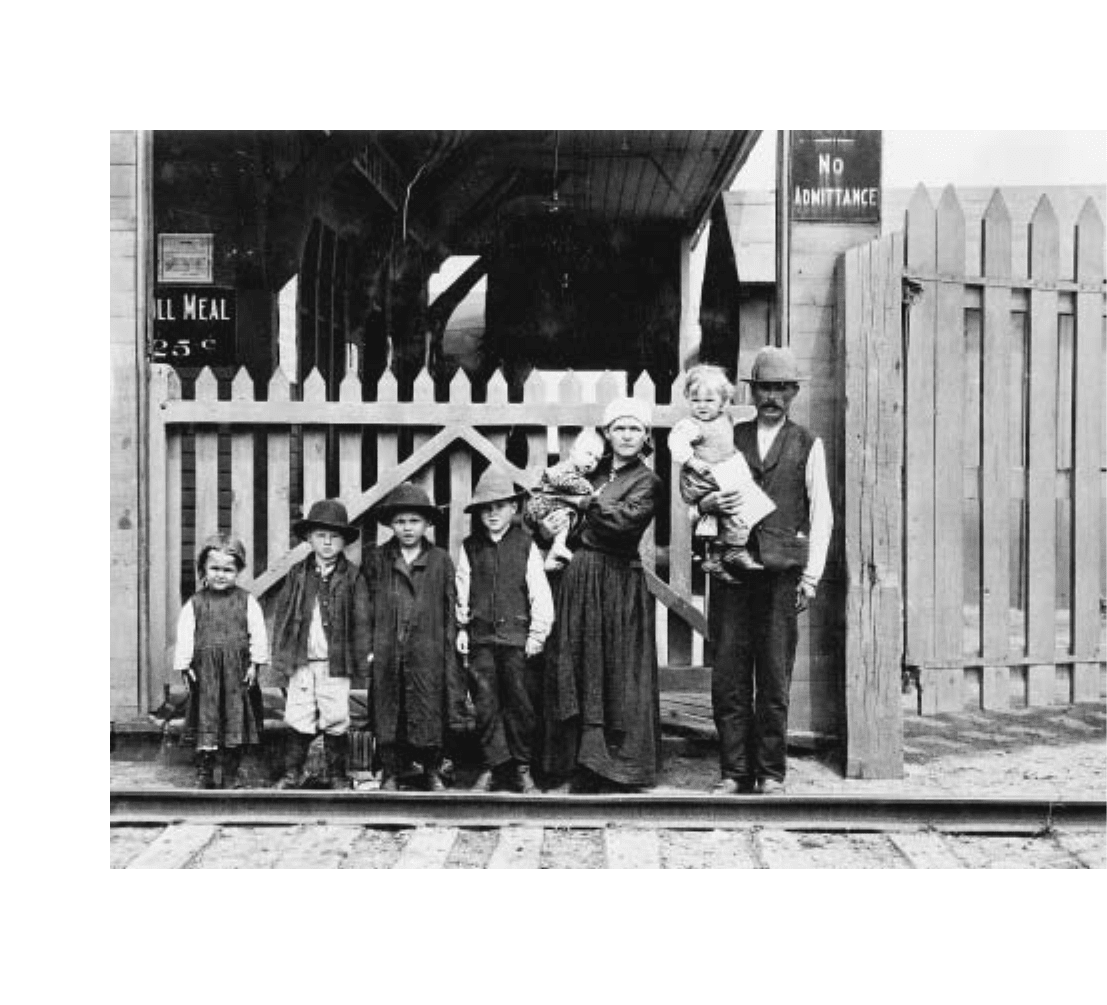

Galician immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire at immigration sheds in Quebec province: Peasant families such as this

were considered ideal immigrants by the Canadian government during the early 20th century. Galicia was a former Austrian

Crown territory, now divided between Ukraine and Poland.

(John Woodruff/National Archives of Canada/C-4745)

and replaced by the successor states of Austria, Hungary,

Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia.

See also A

USTRIAN IMMIGRATION

;C

ROATIAN IMMI

-

GRATION

;C

ZECH IMMIGRATION

;H

UNGARIAN IMMIGRA

-

TION

;J

EWISH IMMIGRATION

;P

OLISH IMMIGRATION

;

R

OMANIAN IMMIGRATION

;S

ERBIAN IMMIGRATION

;S

LO

-

VAKIAN IMMIGRATION

;S

LOVENIAN IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Alexander, J. G. The Immigrant Church and Community: Pittsburgh’s

Slov

ak Catholics and Lutherans, 1880–1915. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Uni-

v

ersity of Pittsburgh Press, 1987.

Avery, Donald. Reluctant Host: Canada’s Response to Immigrant Work-

ers, 1896–1994. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1995.

Chmelar

, John. “The Austrian Emigration, 1900–1914.” Perspectives

in American H

istory 7 (1973): 275–378.

Frajlic, F

rances. “Croatian Migration to and from the United States

between 1900 and 1914.” Ph.D. diss., New York University,

1975.

Greene, Victor. For God and Country: The Rise of Polish and Lithuanian

E

thnic Consciousness in A

merica, 1860–1910. Madison: State His-

torical Society of

Wisconsin, 1975.

Habenicht, Jan. History of Czechs in America. 1910. Reprint, St. Paul:

G

eck and S

lovak Genealogical Society of Minnesota, 1996.

Hoerder, Dirk, and I. Blank, eds. Roots of the Transplanted. New York:

Columbia U

niv

ersity Press, 1994.

Horvath, T., and G. Neyer, eds. Auswanderung aus Österreich. Vienna:

Bohlau V

erlag,

1996.

Korytova-Magstadt, Stepanka. To Reap a Bountiful Harvest: Czech

Immigration beyond the Mississippi, 1850–1900. Iowa City, Iowa:

Rudi Publishing, 1993.

Laska, V

., ed. The Czechs in America, 1633–1977: A Chronology and

F

act Book. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana Publications, 1978.

Lengyel, E

mil. Americans from Hungary. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott,

1948.

O

key

, Robin. The Habsburg Monarchy: From Enlightenment to Eclipse.

New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

Prisland, M. From Slovenia to America. C

hicago: Slovenian Women’s

Union of America, 1968.

Puskas, Julianna. From Hungary to the United States (1880–1914).

Budapest: Akademiai Kiado, 1982.

Rasporich, Anthony

W

. For a Better Life: A History of the Croatians in

Canada. T

oronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1982.

Schlag, W

illiam. “A Survey of Austrian Emigration to the United

States.” In Österreich und die angelsächsische Welt. Ed. Otto von

H

ietsch.

Vienna, Austria, and Stuttgart, Germany: W.

Braumüller, 1961.

Spaulding, E. Wilder. The Quiet Invaders: The Story of the Austrian

I

mpact upon A

merica. Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag,

1968.

Stolarik, M. M

ar

k. Immigration and Urbanization: The Slovak Experi-

ence, 1870–1918. M

inneapolis, Minn.: AMS Press, 1974.

Sz

abo, F., F. Engelmann, and M. Prokop, eds. Austrian Immigration

to Canada. Ottawa: Carleton U

niv

ersity Press, 1996.

Széplaki, Joseph, ed. The Hungarians in America, 1583–1974: A

Chronology and Fact Book. Dobbs Ferry

, N.Y.: Oceana Publica-

tions, 1975.

Taylor, A. J. P. The H

absburg Monarchy, 1809–1918: A History of the

Austrian Empir

e

and Austria-Hungary. London: H. Hamilton,

1941.

22 AUSTRO-HUNGARIAN IMMIGRATION

Baltimore, Lord See M

ARYLAND COLONY

.

Baltimore, Maryland

The city of Baltimore’s population has been in decline

throughout much of the 20th century. While the subur-

ban county population continues to grow with the devel-

opment of the Baltimore–Washington, D.C., corridor, the

city population in 2001 was 635,210, down 11.5 percent

from 1990.

Baltimore became an important port of entry for

immigrants during the 1820s. As the eastern terminus of

the National (Cumberland) Road that ran across the

Appalachian Mountains, it was a natural starting point for

recently arrived immigrants seeking land in the interior

of the country. Like most Atlantic seaboard cities, Balti-

more received significant numbers of French exiles dur-

ing the French Revolution and the early part of the

ensuing revolutionary wars (1789–95). By 1860, more

than one-third of the population was foreign born,

including large German and Irish communities. During

the great wave of new immigration between 1880 and

1920, Baltimore, and most eastern seaboard ports,

received immigrants from dozens of countries, with Ital-

ian and Greek communities becoming especially promi-

nent. Baltimore was not a popular immigrant destination

after 1920.

See also M

ARYLAND COLONY

.

Further Reading

Fein, Isaac. The Making of an American Jewish Community: The History

of Baltimore Jewry from 1773–1920. Philadelphia: Jewish Publi-

cation Society of America, 1971.

O

lesker

, Michael. Journeys to the Heart of Baltimore. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Olson, Sherry H. Baltimore: The Building of an A

merican City. Rev. ed.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Sandler, Gilbert. Jewish B

altimore: A Family Album. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins U

niversity Press, 2000.

Stolarik, M. Mark, ed. Forgotten Doors: The Other Ports of Entry to the

U

nited S

tates. Philadelphia: Balch Institute Press, 1988.

Bangladeshi immigration

In the U.S. census of 2000 and the Canadian census of

2001, 57,412 Americans and 13,080 Canadians claimed

Bangladeshi descent, though the numbers are speculative.

Between 1981 and 1998, legal immigrants from Bangladesh

to the United States numbered 68,000, but it was generally

conceded that the actual number was twice as great. Most

Bangladeshis (sometimes referred to as Bengalis or Bangalis)

came as students, though many were secondary migrants

from Saudi Arabia, Oman, Dubai, and Kuwait. They were

concentrated in large urban areas, particularly New York

City, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Georgia, and Miami, Florida.

Almost 90 percent of Bangladeshi Canadians live in urban

centers throughout Ontario and Quebec.

23

B

4