Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Bangladesh occupies 51,600 square miles of South Asia

between 21 and 27 degrees north latitude and is almost

entirely surrounded by India, to the north, east, and west.

The Bay of Bengal lies to the south and Myanmar to the

southeast. The land is mostly flat and lies in a wet tropical

climate zone dominated by the Ganges and Brahmaputra

Rivers. In 2002, the population was estimated at

131,269,860, with more than 12 million in the urban area

of Dhaka. Ninety-eight percent of the population is Bengali,

while the remainder is Bihari or tribal. Islam is the predom-

inant religion and is practiced by 88 percent of the popula-

tion; 11 percent are Hindus. Hindus occupied Bangladesh

until the 12th century when Muslims invaded. Britain

gained control of the region in the 18th century and in 1905

partitioned the region into Muslim and Hindu areas, pre-

saging the eventual partition of India in 1947 along religious

lines and dividing the Bengali people. At the time of parti-

tion, East Bengal was joined with the Muslim areas of west-

ern India, more than 1,000 miles away, to became a

province of the new state of Pakistan. In 1971, civil war

broke out between Pakistan and troops in the east. Pakistan

surrendered after India joined the war in which 1 million

died and 10 million refugees fled to India. Bangladesh’s

independence was declared in December 1971. During the

1970s much of the economy was nationalized as the coun-

try came under the influence of India and the Soviet Union.

Following several military coups, Bangladesh was declared

an Islamic republic in 1988. Three years later a parliamen-

tary democracy was declared. Bangladesh, one of the poor-

est countries in the world, has been subject to many natural

disasters, including a 1991 cyclone that killed more than

131,000 people. Cyclones and floods regularly displace mil-

lions in a land of high population density and low-lying

land.

Bengali immigrants began arriving in the United States

as early as 1887, though their numbers remained small due

to discriminatory legislation. Some were Hindu and Muslim

activists who fled following the British partition of the

region into Hindu and Muslim zones in 1905. Almost all

early immigrants were single men, many of whom married

Mexican or mixed-race women. During the first wave of

immigration following independence in 1971, most immi-

grants were well-educated professionals, fleeing the political

turmoil of their country and frequently granted refugee sta-

tus. As late as 1980, there were still fewer than 5,000 for-

eign-born Bangladeshis in the United States, though their

numbers steadily increased through the end of the century.

During the 1990s, the minority Chittagong Hills people

were more frequent immigrants, escaping political repres-

sion in Bangladesh. Between 1992 and 2002, almost 70,000

Bangladeshis were admitted to the United States.

Throughout the 19th century many educated Bengalis

became part of the British colonial establishment, playing a

large role in the nationalist movement and occasionally

immigrating to various parts of the empire, including

Canada, though their numbers were very small. In the first

decade of uncertainty following independence, fewer than

1,000 Bangladeshis immigrated to Canada, joining perhaps

twice that number from the Indian state of Bengal. The

number of immigrants began to rise gradually during the

1970s, then more significantly after the mid-1980s, as ear-

lier immigrants began to sponsor their family member. Of

21,595 Bangladeshis in Canada in 2001, more than 81 per-

cent entered the country between 1991 and 2001.

See also I

NDIAN IMMIGRATION

;P

AKISTANI IMMIGRA

-

TION

;S

OUTH

A

SIAN IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Baxter, Craig. Bangladesh: From a Nation to a State. Boulder, Colo.:

Westvie

w Press, 1997.

Buchignani, Norman, and Doreen M. Indra, with Ram Srivastava.

Continuous Journey: A Social History of South Asians in Canada.

Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1985.

Hossain, Mokerr

om. “S

outh Asians in Southern California: A Socio-

logical Study of Immigrants from India, Pakistan and

Bangladesh.” South Asia Bulletin 2, no. 1 (Spring 1982): 74–83.

Jensen, J

oan M. Passage from India: Asian Indian Immigrants in North

A

merica. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1988.

Johnston, H

ugh. The East Indians in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian His-

torical Association, 1984.

Leonar

d, Kar

en Isaksen. South Asian Americans. Westport, Conn.:

Gr

eenwood Press, 1997.

Novak, J. J. Bangladesh: Reflections on the Water. Bloomington: Indiana

U

niv

ersity Press, 1993.

Petivich, Carla. The Expanding Landscape: South Asians in the Dias-

por

a. Chicago: M

anohar, 1999.

Rahim, Aminur. “

After the Last Journey: Some Reflections on

Bangladeshi Community Life in Ontario.” Polyphony 12, nos.

1–2 (1990): 8–11.

Sisson, R., and L. E. Rose. War and Secession: Pakistan, I

ndia, and the

C

reation of Bangladesh. Berkeley: University of California Press,

1990.

T

inker

, Hugh. The Banyan Tree: Overseas Emigrants from India, Pak-

istan, and Bangladesh. N

ew York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Van der

Veer, Peter, ed. Nation and Migration: The Politics of Space in

the South Asian Diaspor

a. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylva-

nia Pr

ess, 1995.

Barbadian immigration

As the most densely populated island nation in the

Caribbean Sea, Barbados has long experienced strong demo-

graphic pressures resulting in emigration. At first, Barbadi-

ans focused on labor opportunities in the Caribbean basin;

however, after World War II (1939–45), Barbadians increas-

ingly sought access to the United States, Canada, and Great

Britain. In the U.S. census of 2000 and the Canadian census

of 2001, 54,509 Americans and 23,725 Canadians claimed

Barbadian descent. The largest concentration in the United

24 BARBADIAN IMMIGRATION

States by far is in New York City; in Canada, it is in Toronto

and to a lesser extent Montreal.

Barbados is an Atlantic island occupying 170 square

miles of the eastern West Indies near 13 degrees north lati-

tude. St. Lucia and St. Vincent are the nearest islands and lie

to the west. The island of Barbados is somewhat mountain-

ous and is surrounded by coral reefs. In 2002, the popula-

tion of Barbados was estimated at 275,330 and was

principally black. Two-thirds of the population were Protes-

tant Christians, while a small percentage practiced Roman

Catholicism. British colonists first settled Barbados in 1627,

establishing plantations to take advantage of the lucrative

sugar trade. The island became one of the main importers of

African slaves. During the 17th and 18th centuries, planters

sometimes invested their plantation wealth in the American

colonies, particularly the Carolinas. Black emigration came

after emancipation in 1838, though the numbers remained

small until the 20th century. Barbados began to move

toward independence in the 1950s and in 1958 joined nine

other Caribbean dependencies to form the Federation of the

West Indies within the British Commonwealth. The federa-

tion dissolved in 1962, and Barbados became fully inde-

pendent in 1966.

Early immigration figures for Barbados are only esti-

mates. Prior to the 1960s, both the United States and

Canada categorized all immigrants from Caribbean basin

dependencies and countries, as “West Indians.” Due to the

shifting political status of territories within the region dur-

ing the period of decolonization (1958–83) and special

international circumstances in some areas, the concept of

what it meant to be West Indian shifted across time, thus

making it impossible to say with certainty how many immi-

grants came from Barbados. Also, migration from island to

island within the Caribbean was common, making statistics

after the 1960s less than reliable (see W

EST

I

NDIAN IMMI

-

GRATION

).

Black Barbadians had been migrating as workers to

Guyana, Panama, and Trinidad from the 1860s, but it was

not until the turn of the 20th century that they came to the

United States in significant numbers. Between 1900 and

1924, about 100,000 West Indians, including significant

numbers of Barbadians, immigrated to the United States,

many of them from the middle classes. The restrictive

J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

(1924) and economic depression in

the 1930s virtually halted Barbadian immigration. Barba-

dian workers were among 41,000 West Indians recruited for

war work after 1941, but isolationist policies of the 1950s

kept immigration low until passage of the Immigration Act

of 1965. It is estimated that more than 50 percent of Barba-

dian immigrants prior to 1965 were skilled or white-collar

workers. The M

C

C

ARRAN

-W

ALTER

I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZATION

A

CT

of 1952 established an annual quota

of only 800 for all British territories in the West Indies,

including Barbados. When Barbados gained full indepen-

dence from Britain in 1966, in a new wave of immigration

that was dominated by workers, Barbadian immigrants con-

tinued to head to the northeast, with 73 percent of them liv-

ing in Brooklyn, New York, by 1970. Though overall

numbers of immigrants remained relatively small, averaging

less than 2,000 per year since 1965, Barbadians were gener-

ally better educated than most Caribbean immigrants and

thus fared better economically and exercised a dispropor-

tionate share of leadership. By 1990, the total number of

Barbadian Americans was 33,178, with almost three-quar-

ters of them being foreign born. Between 1992 and 2002, an

average of about 800 Barbadians immigrated to the United

States each year.

Restrictive elements of the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1952

in Canada excluded most black immigration, though a spe-

cial program was instituted in 1955 to encourage the immi-

gration of Barbadian and Jamaican domestic workers “of

exceptional merit.” Single women with no dependents,

healthy, and having had at least an eighth-grade education

qualified for landed immigrant status in return for a one-

year commitment to domestic service. This program, con-

tinued until 1967 when the nonracial point system was

introduced for determining immigrant qualifications,

brought perhaps 1,000 Barbadian women to Canada.

Caribbean immigration to Canada peaked between

1973 and 1978, when West Indians composed more than

10 percent of all immigrants to Canada. A substantial num-

ber of these were Barbadians, almost all coming for economic

opportunities. The proportion can be inferred from the

number of immigrants living in Canada in 2001. Among

almost 300,000 West Indian immigrants, Barbados had the

fourth-highest number (14,650), behind Jamaica (120,210),

Trinidad and Tobago (65,145), and Haiti (52,625). Of those,

more than 63 percent (more than 9,000) arrived during the

1960s and 1970s; fewer than 2,000 arrived between 1991

and 2001. The proportion of women to men remains high,

primarily because of the domestic workers’ program of the

1950s and 1960s. There is an additional but undetermined

number of Barbadians (perhaps a thousand or more) who

came as part of the “double lap” migration, immigrating first

from Barbados to Great Britain and then to Canada. A grow-

ing racism in Britain is often cited by “double lap” migrants

as their cause for leaving.

See also

IMMIGRATION REGULATIONS

.

Further Reading

Beckles, Hilary McDonald. A History of Barbados: From Amerindian

S

ettlement to Nation-State. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Pr

ess, 1990.

Bristow, Peggy, et al., eds. “We’re Rooted Here and They Can’t Pull Us

U

p

”: Essays in African Canadian Women’s History. Toronto: Uni-

versity of

Toronto Press, 1994.

Calliste, Agnes. “Canada’s Immigration Policy and Domestics from

the Caribbean: The Second Domestic Scheme.” In Race, Class,

BARBADIAN IMMIGRATION 25

Gender: Bonds and Barriers. Socialist Studies: A Canadian Annual,

vol. 5. Ed. Jesse Vorst. Toronto: Between the Lines, 1989.

———. “Women of ‘Exceptional Merit’: Immigration of Caribbean

Nurses to Canada.” Canadian Journal of Women and the Law 6

(1993): 85–99.

Gmelch, G. Double Passage: The Lives of Caribbean Migrants Abroad

and Back Home. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992.

Howe, G., and Don D. Marshall, eds. The Empowering Impulse: The

Nationalist Tradition of Barbados. Kingston, Jamaica: Canoe

Press, 2001.

Kasinitz, Philip. Caribbean New York: Black Immigrants and the Poli-

tics of Race. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1992.

Kent, David L. Barbados and America. Arlington, Va.: C. M. Kent,

1980.

LaBrucherie, Roger A. A Barbados Journey. Pine Valley, Calif.: Ima-

genes Press, 1985.

Levine, Barry, ed. The Caribbean Exodus. New York: Praeger, 1987.

Owens-Watkins, Irma. Blood Relations. Bloomington: University of

Indiana Press, 1996.

Palmer, R. W. Pilgrims from the Sun: West Indian Migration to Amer-

ica. New York: Twayne, 1995.

Richardson, Bonham. Caribbean Migration. Knoxville: University of

Tennessee Press, 1983.

Tennyson, Brian Douglas. Canada and the Commonwealth Caribbean.

Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1988.

Walker, James W. St. G. The West Indians in Canada. Ottawa: Cana-

dian Historical Association, 1984.

Westmoreland, Guy T., Jr. West Indian Americans. Westport, Conn.:

Greenwood Press, 2001.

Winks, Robin. Canadian-West Indian Union: A Forty-Year Minuet.

London: Athlone Press, 1968.

Barnardo,Thomas John (1845–1905) social

reformer

Thomas John Barnardo was best known for his philan-

thropic work among London’s destitute children. As a result

of his efforts, some 20,000

HOME CHILDREN

were dis-

patched to Canada as agricultural and domestic apprentices

in order to remove them from the evils of urban London.

Barnardo was born in Dublin, Ireland. After convert-

ing to evangelical Christianity (1862), he preached in

Dublin’s slums. In 1866, he traveled to London to study

medicine, with a view toward joining the China Inland

Mission. While still in school, he was drawn to the plight of

26 BARNARDO,THOMAS JOHN

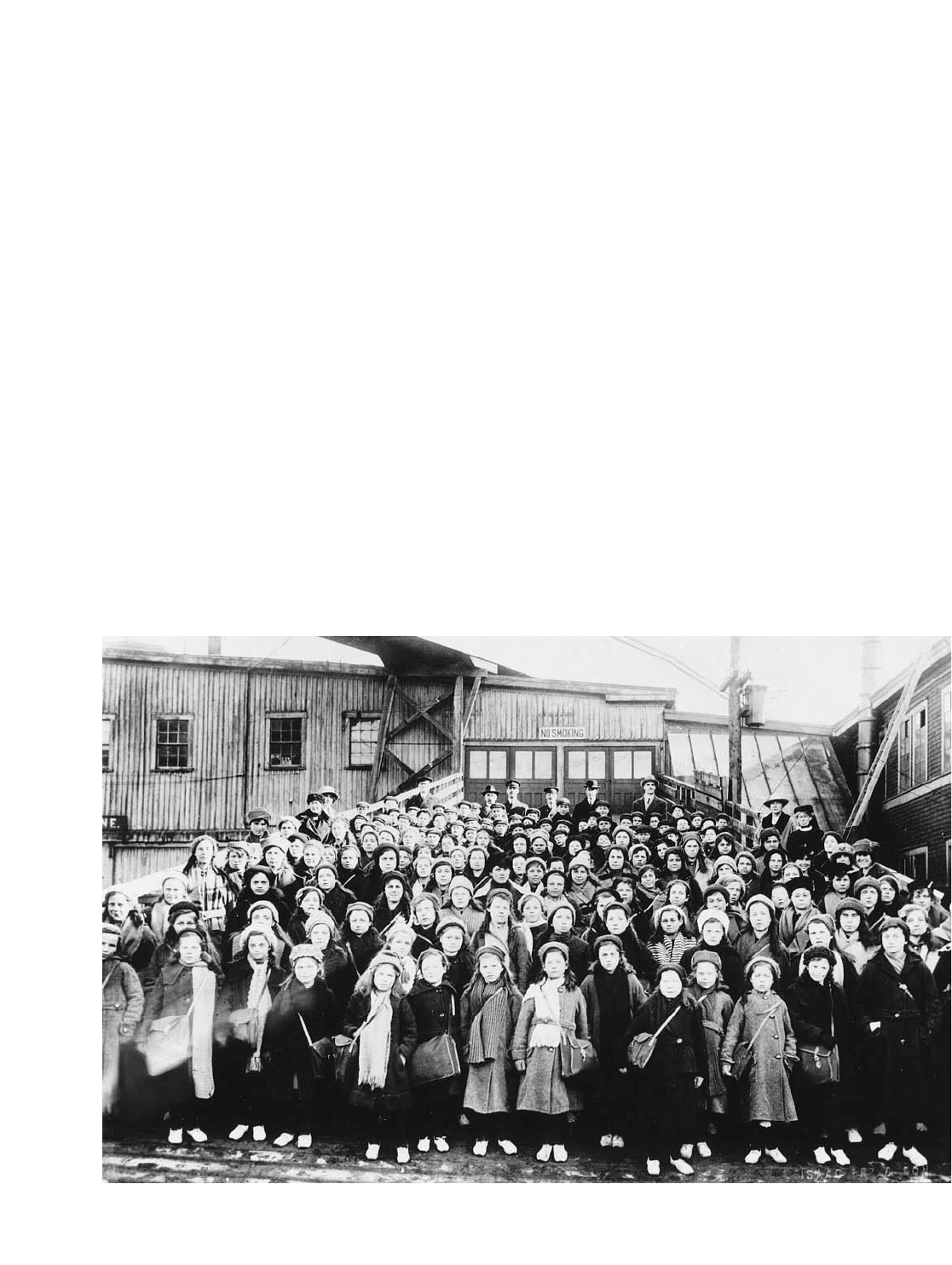

Immigrant children from Dr. Thomas John Barnardo’s homes at Landing Stage, St. John, New Brunswick, ca. 1905. Barnardo’s

homes for destitute children eventually brought more than 30,000 British children to Canada as apprentices between the 1880s

and the 1930s.

(National Archives of Canada/PA-41785)

London waifs and in 1867 founded the East End Juvenile

Mission in Stepney. A powerful speaker, Barnardo

addressed the Missionary Conference in 1867 and soon

enlisted the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury and banker Robert

Barclay to help establish the first of his homes for destitute

children (1868), soon known as “Dr. Barnardo’s homes.”

Barnardo abandoned his medical studies after 1870 in order

to devote himself full time to the cause of homeless chil-

dren. With a charter stating that “no destitute child” would

ever be refused admission, by 1878 he had established 50

homes in the capital. He also was an active supporter of leg-

islation promoting the welfare of children.

As early as 1872, Barnardo was sending destitute chil-

dren to Canada through an emigration network run by a

Quaker activist, Annie Macpherson. By 1881, he became

convinced that emigration offered the best hope for most of

London’s poor children. After visiting Canada and speaking

with government officials, he established homes there and

arranged to apprentice thousands of slum children in rural

Canadian areas. At the time of his death, more than 12,000

children were either resident in his homes or boarded out to

others. It is estimated that Barnardo’s homes were responsi-

ble for sending some 30,000 children to Canada. They con-

tinued to be sent to Canada until 1939, as well as to

Australia into the 1960s.

Further Reading

Barnardo, Syrie Louise Elmsie. Memoirs of the Late Dr. Barnardo. Lon-

don: Hodder and Stoughton, 1907.

Rose, June. For the S

ake of the Children: Inside Dr. Barnardo’

s, 120

Years

of Caring for Children. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1987.

Williams, Ar

thur E. The Adventures of Dr. Barnardo. 3d ed. London:

Allen, 1966.

Wymer, Norman. Dr. Barnar

do. London: Oxford University Press,

1954.

Barr colony

The Barr colony was the attempt of two Anglican clergymen

to establish a British colony in 1903 in remote

Saskatchewan, almost 200 miles northwest of Saskatoon.

Although few of the 2,000 original settlers had any agricul-

tural experience and the administration of the colony was a

disaster, the coming of the railway in 1905 guaranteed its

existence.

Reverend Isaac Barr had hoped to join forces with the

British colonial administrator Cecil Rhodes in extending the

British Empire into western Canada (see C

ANADA

—

IMMI

-

GRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

). With Rhodes’s

death in 1902, Barr joined Reverend George Lloyd in his

plan for settling unemployed British workers and soldiers

demobilized following the Boer War (1899–1902). Barr

negotiated with the Canadian government to reserve a block

of land for his settlers and arranged for them to be trans-

ported on the SS Lake Manitoba, equipped to handle less

than one-thir

d the total number of immigrants. After

numer

ous organizational disasters, the colonists deposed

Barr and elected Lloyd leader. In 1905, Saskatchewan was

organized as a province of the Dominion of Canada.

Further Reading

Macdonald, Norman. Canada: Immigration and Colonization,

1841–1903. T

oronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1966.

Timlin, M

abel. “Canada’s Immigration Policy, 1896–1910.” Canadian

Journal of E

conomics and Political Science 26 (1960): 517–532.

Basque immigration

The Basques make up a very small proportion of European

immigration to North America. In the U.S. census of 2000

and the Canadian census of 2001, 57,793 Americans and

2,715 Canadians claimed Basque descent, though the num-

bers probably underrepresent the actual figure. Until 1980,

Basque Americans were included by the U.S. Immigration

and Naturalization Service in aggregate figures for Spain and

France. The majority of Basque Americans live in California.

Canadian Basques are spread throughout the country.

Though they traditionally worked the eastern fisheries and

settled in Quebec, there is a substantial and growing com-

munity in Ontario, as well as other settlement in New-

foundland, Nova Scotia, and British Columbia.

The Basque homeland is a historic region in the western

Pyrenees Mountains, extending from southwestern France

to northern Spain and the Bay of Biscay. Almost 90 percent

of the region is in Spain, and all but about 200,000 of

almost 3 million inhabitants are on the Spanish side of the

line. The Basques are racially and linguistically unlike either

the French or the Spanish, and the origins of their non-

Indo-European language remain a mystery. The Kingdom of

Navarre was largely a Basque state and managed to maintain

its independence until the 16th century, when it came under

the formal control of its two large neighbors. In 1512, Spain

and France signed a treaty dividing their territory. Because

the Basques had resisted the Moorish invasion of the

Iberian Peninsula, they were granted significant privileges

that enabled them to hold important government and

church positions in the Spanish colonial bureaucracy. In

1980, Spain constituted the provinces of Álava, Guipúzcoa,

and Vizcaya as an autonomous community known as the

Basque Country. Radical factions among the Basques were

dissatisfied and began a terrorist campaign to gain complete

independence.

Basques have had a tendency to migrate throughout

their history, in part because of a strong seafaring tradition.

They made up the largest ethnic contingent in Christopher

Columbus’s voyages to the New World and served routinely

on crews exploring the coasts of the Americas. They also

played major roles in the Spanish exploration, settlement,

BASQUE IMMIGRATION 27

and governance of the Americas between the 16th and 18th

centuries. The upheavals of the French Revolution and ensu-

ing revolutionary wars (1789–1815) and Basque support for

the defeated pretender to the Spanish throne, Don Carlos,

led thousands more to emigrate in the 19th century; most

went to South America and Mexico. Whereas the earlier

Basques had generally been of aristocratic background, most

of the second wave were of modest circumstances.

Basque immigration to the United States began in

earnest during the California gold rush (1848), when South

American Basques tried their hand in the goldfields. Most

eventually went back to the sheep grazing that they had

transported from the Old World to South America. By the

1870s, Basque shepherds were in every western U.S. state.

Given that few Basques learned English and that most were

isolated by their seminomadic work, they were often derided

and exercised little political clout. They nevertheless con-

tinued to recruit family members from Europe until restric-

tive immigration legislation was passed in the 1920s. As a

result of the Taylor Grazing Act (1934), free access to pub-

lic lands was ended and with it much of the viability of

Basque shepherding that depended upon the free movement

of sheep from mountain pastures to valley grazing. Under

the J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

(1924), Spain’s entire annual

quota was reduced to only 121 immigrants, virtually end-

ing Basque immigration. As a result of the economic dis-

locations of World War II (1939–45), Basque shepherds

were in much demand. Under pressure from groups like

the Western Range Association, special legislation was

passed to exempt them from the Spanish quota, enabling

more than 5,000 to come between 1957 and 1970, though

many of them were required to return to Europe after three

years. As the Basque economy improved in the 1970s,

immigration to the Americas was not viewed as an attrac-

tive option. By the mid-1990s, the number of Basque-

American shepherds had dropped from 1,500 to a few

dozen. While Los Angeles was the early center of Basque

settlement in the United States, by the mid-20th century

Basques had spread widely throughout the grazing lands of

the West. Those settling in California, Arizona, New Mex-

ico, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and central Nevada

tended to be from Navarra and France; those in northern

Nevada, Idaho, and Oregon, principally from the Vizcaya

province of Spain.

Basques were regularly fishing in Canadian waters by

the early 16th century. Although hundreds of Basques

worked the banks and made use of Canadian shores, there

appears to have been no permanent settlements until the

1660s, when the French government founded Plaisance in

Newfoundland. Inhabited mainly by Basque fishermen, the

colony was handed over to the British by the Treaty of

Utrecht in 1713, when most of the inhabitants moved to

Île Royale (Cape Breton). Although their numbers remained

small, they often came from prominent families and served

in responsible positions of government. Between 1718 and

1758, for instance, the king’s commander of the Labrador

coast was a Basque Canadian. Most Basques in Canada

remained itinerants, however, with permanent residents of

N

EW

F

RANCE

seldom numbering more than 120. Although

a handful of French Basques continued to settle the Mag-

dalen Islands and along the St. Lawrence Seaway, their num-

bers remained very small until early in the 20th century. In

1907, about 3,000 Basque fishermen migrated from Saint-

Pierre and Miquelon to Montreal, hoping to improve their

economic condition, though most eventually returned to

their homeland.

Further Reading

Bélanger, René. Les Basques dans l’estuaire du Saint-Laurent. Mon-

treal: P

resses de l’Université du Quebec, 1971.

Clark, Robert. The Basques: The Franco Years and Beyond. Reno: Uni-

v

ersity of N

evada Press, 1980.

Decroos, J. F. The Long Journey: Social Integration and Ethnicity Main-

tenance among Urban Basques in the S

an F

rancisco Bay Region.

Reno: Basque Studies Program, University of Nevada, 1983.

D

ouglass,

William. “The Vanishing Basque Sheepherder.” American

West 17 (1980): 30–31, 59–61.

D

ouglass,

William, and John Bilbao. Amerikanuak: Basques in the New

Wor

ld. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1975.

Etulain, Richar

d W., ed. Portraits of Basques in the New World. Reno:

Univ

ersity of Nevada Press, 1999.

Irigaray, Louis, and Theodore Taylor. A S

hepherd Watches, a Shepherd

S

ings: Growing Up a Basque Shepherd in California’s San Joaquin

Valley. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Company, 1977.

Laxalt, R

ober

t. Sweet Promised Land. New York: Harper and Row,

1957.

M

cCall, G. E. B

asque-Americans and a Sequential Theory of Migration

and Adaptation. San Francisco: R. and E. Research Associates, 1973.

Belarusan immigration See R

USSIAN IMMIGRATION

.

Belgian immigration

Belgians were among the earliest settlers in colonial North

America, although they immigrated in significant numbers

only between 1820 and 1920. In the U.S. census of 2000

and the Canadian census of 2001, 360,642 Americans and

129,780 Canadians claimed Belgian descent. Because Bel-

gians assimilated more quickly than many immigrant

groups, there are few distinct Belgian communities in North

America. In the United States, the greatest concentrations

are in Michigan and Wisconsin. In Canada, Belgians are

widely dispersed throughout the country, with Ontario hav-

ing the largest provincial population and Montreal having

the largest urban population.

Belgium occupies 11,700 square miles of western

Europe between 49 and 52 degrees north latitude. A coast-

line on the North Sea forms its northern border along with

28 BELARUSAN IMMIGRATION

the Netherlands. Germany and Luxembourg lie to the east

and France to the west. The land is mostly flat. In 2002, the

population of Belgium was estimated at 10,258,762, three-

quarters of which practice Roman Catholicism. The remain-

ing quarter is Protestant. Dutch-speaking Flemings make up

55 percent of the population and inhabit the north. The

other major ethnic group is the French-speaking Walloons,

who make up another third of the population and inhabit

the southern regions. Ethnic tension continues to cause

political conflict and led the parliament to federalize the

government in 1993.

Belgium was first settled by Celts and then frequently

conquered, beginning with the Romans under Julius Caesar.

Thereafter the Franks, Burgundy, Spain, Austria, and France

controlled the region until Belgium was made part of the

Netherlands in 1815. In 1624, Walloon Protestants

migrated to New Holland (later N

EW

Y

ORK

) seeking greater

religious freedom, though these early colonial migrants were

few. A few Belgian artisans also settled in N

EW

F

RANCE

after

1663. Belgium gained independence in 1830, when its ter-

ritorial integrity was guaranteed by the major powers. Eco-

nomic opportunity, however, far outweighed religious or

political factors in the choice of poor Belgian farmers to emi-

grate. With Belgium rapidly growing and in the vanguard of

the European Industrial Revolution, farmers were rapidly

displaced and after 1840 were encouraged by their govern-

ments to emigrate, though more than 80 percent chose to

stay in Europe prior to the 1880s. About 63,000 Belgians

came to the United States before 1900 and another 75,000

between 1900 and 1920. As many as 18,000 Walloons may

first have migrated to Canada before crossing over into the

United States. Prior to 1910, there were fewer than 10,000

Belgians in Canada, but another 20,000 arrived before

1930, with most settling in Manitoba and the prairie

provinces. In the Canadian I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1869,

Belgians were listed as a “preferred” group, and their farmers

remained in high demand. After 1930, immigrants were

more frequently artisans, skilled workers, or professionals.

Though many Belgians in both the United States and

Canada assimilated quickly—the Flemings with the Dutch,

and the Walloons with the French and French-Canadians—

a Walloon-speaking enclave remained into the 21st century

in the Door Peninsula of northeastern Wisconsin. By 1860,

Belgians owned 80 percent of a three-county area northeast

of Green Bay.

As a result of German invasions in 1914 and 1940,

small numbers of Belgians were admitted to the United

States and Canada as refugees during both World War I and

World War II. The disruptions of World War II led large

numbers of Belgians to seek economic opportunity in North

America. Between 1945 and 1975, almost 40,000 immi-

grated to Canada and a similar number to the United States.

From the 1980s, numbers were small, generally well below

quotas, and most often represent well-educated profession-

als seeking career opportunities. Between 1992 and 2002,

Belgian immigration to the United States averaged annually

a little more than 600. Of 19,765 Belgian Canadians iden-

tified in the 2001 census, almost half immigrated prior to

1961, and only 2,185 between 1991 and 2001.

Further Reading

Amato, Joseph. Servants of the Land: God, Family and Farm: The Trin-

ity of B

elgian Economic Folkways in Southwestern Minnesota. Mar-

shall, Minn.: C

rossings Press, 1990.

Bayer, Henry G. The B

elgians: First Settlers in New York. New York:

D

evin-Adair Co., 1925.

Holand, H. Wisconsin’s Belgian Community. Sturgeon Bay, Wis.: Door

County H

istorical S

ociety, 1933.

Jaenen, Cornelius J. The Belgians in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian His-

torical Association, 1991.

K

urgan, G

inetterand E. Spelkens. Two Studies on Emigration through

Antwerp to the N

ew World. Brussels, Belgium: Center for Ameri-

can S

tudies, 1976.

Laatsch, W. G., and C. Calkins. “Belgians in Wisconsin.” In To Build

a New Land: Ethnic Landscapes in North A

merica. Ed. A. G.

Noble. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Lucas, Henry. Netherlanders in America. Ann Arbor: University of

Michigan Press, 1955.

M

agee, J

oan. The Belgians in Ontario: A History. Toronto: Dundurn,

1987.

Sabbe, Philemon D., and Leon Buyse. Belgians in America. Thielt, Bel-

gium: Lannoo, 1960.

Wilson, Keith, and James B. Wyndels. The Belgians in Manitoba. Win-

nipeg: Peguis, 1976.

Bill C-55 (Canada) (1989)

With the Canadian Supreme Court’s decision in S

INGH V

.

M

INISTER OF

E

MPLOYMENT AND

I

MMIGRATION

(1985) that

oral hearings were required in every case for the determina-

tion of refugee status, there was an immediate need to

restructure the hearing process. The first Bill C-55 (1986),

proposed as an amendment to the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of

1976, dramatically increased the maximum number of

potential refugee-claim adjudicators. The maximum num-

ber of members of the Immigration Appeal Board (IAB) was

raised from 18 to 50, and of vice-chairs from five to 13.

The new administrative machinery was nevertheless unable

to meet the backlog of hearings, which extended to more

than three years. At the same time, many immigrants

claimed refugee status in the hope that the backlog of cases

might lead to grants of amnesty. There were concerns on

both sides of the political spectrum, leading to a bitter and

protracted debate over Canada’s immigration policy. On

the Right, there was widespread concern over unregulated

immigration and abuse of the system; on the Left, over

human rights and procedural fairness.

While the backlog of hearings mounted, there were two

celebrated cases, one in which ships carrying undocumented

BILL C-55 29

Tamils (1986) and Sikhs (1987) landed on Canadian shores

and another concerning an influx of refugee claimants from

Portugal and Turkey. A second Bill C-55 (the Refugee

Reform Bill, introduced 1987) restructured the process for

determining refugee status, replacing the IAB with the

Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB), which had two divi-

sions, the Immigration Appeals Division (IAD) and the

Convention Refugee Determination Division (CRDD). It

also provided for a two-stage hearing process. In the first

stage, which sought to eliminate patently unfounded claims,

a preliminary joint inquiry by an independent adjudicator

and a CRDD member would first determine a claimant’s

admissibility. The second stage of the process involved a full

hearing before two members of the CRDD. The companion

Bill C-84 (introduced 1987) increased penalties for smug-

gling refugees, levied heavy fines for transporting undocu-

mented aliens, and extended government powers of search,

detention, and deportation. Both measures were widely

opposed by liberals and more than 100 organizations,

including the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, the

Inter-Church Committee on Refugees, and the Canadian

Bar Association. The major criticisms were that no hearing

was guaranteed before the IRB at the first stage of eligibility

screening and that provisions for a “safe country” while

awaiting the results of the hearing were not adequate. Both

measures were passed in 1988 and became effective in 1989.

Further Reading

Creese, Gillian. “The Politics of Refuges in Canada.” In Deconstruct-

ing a Nation. E

d. Vic Satzewich. Halifax, Canada: Fernwood,

1992.

D

i

rks, Gerald E. Controversy and Complexity: Canadian Immigration

Policy during the 1980s. M

ontreal and Kingston, Canada:

McG

ill–Queen’s University Press, 1995.

Glenn, H. Patrick. Refugee Claims, the Canadian State and North

A

merican R

egionalism in Hemispheric Integration, Migration and

Human Rights. Toronto: York University Centre for Refugee

S

tudies, 1994.

K

elley, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

H

istor

y of Canadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

Tor

onto Press, 1998.

Plaut, W. G. Refugee Determination in Canada. Ottawa: Minister of

S

upply and S

ervices, 1985.

Bill C-86 (Canada) (1992)

One of the earliest measures designed to deal with the threat

of terrorism, Bill C-86 was introduced in the House of

Commons on June 16, 1992, as an alteration to the I

MMI

-

GRATION

A

CT

of 1976. The Conservative government

argued that in the post–

COLD WAR

era, there were few

refugees from communist regimes, for whom the refugee

provisions were principally designed, but many potential

immigrants with ties to globalized crime syndicates and ter-

rorist organizations. The measure gave the government

greater powers to exclude persons suspected of ties to crimi-

nal or terrorist organizations, and gave medical examiners

more authority in screening those deemed medically inad-

missible. It also provided for fingerprinting and videotap-

ing of refugee hearings. In streamlining the refugee

determination process, the two-stage hearing of B

ILL C

-55

was replaced by a single hearing, with a senior immigration

officer given authority to make a determination regarding

refugee status. The most controversial aspect of the bill pro-

hibited admission from a “safe” third country prepared to

grant refugee status. Many groups, including B’

NAI

B’

RITH

and the Canadian Ethnocultural Council objected, fearing

that political rather than humanitarian standards would be

applied in determining how safe a refugee would be in

another country. The government defended the provision

as an encouragement to other countries to aid in the pro-

tection of refugees. Although opposition by humanitarian,

religious, legal, and ethnic organizations led to a modifica-

tion of some of the more stringent provisions, the bill was

largely implemented as designed.

Further Reading

Badets, Jane, and Tina Chui. Canada’s Changing Immigrant P

opulation.

Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 1994.

Kelley, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

History of Canadian I

mmigr

ation Policy. Toronto: University of

T

oronto Press, 1998.

Stoffman, Daniel. Toward a More Realistic I

mmigr

ation Policy for

Canada. Toronto: C. D. Ho

we Institute, 1993.

Swan, Neil, et al. The Economic and Social Impacts of Immigration.

Ottawa: Economic Council of Canada, 1991.

B’nai B’rith (Children of the Covenant)

B’nai B’rith is the largest Jewish service organization in the

world, with 500,000 members in some 58 countries. I

t has

traditionally promoted greater understanding of Jewish cul-

ture, a heightened sense of Jewish identity, and protection of

human rights generally. Its major component organizations

include the Hillel Foundation for college students, the

A

NTI

-D

EFAMATION

L

EAGUE

(ADL), and B’nai B’rith

Women.

The organization was founded by 12 German Jewish

Americans in New York City in 1843 in order to protect

Jewish rights around the world and to serve the greater needs

of humanity. It became active in Canada in 1875. During

the 19th century, members spoke out against the threat-

ened expulsion of Jews from several states during the Civil

War, raised money for cholera victims in Palestine, and

raised awareness of the persecution of Jews in Romania and

Russia. In the 20th century, the organization became more

directly involved in public policy, especially through the

activities of the ADL. B’nai B’rith regularly monitors the

activities of the United Nations and the European Union

30 BILL C-86

and has played a significant role in bringing Nazi war crim-

inals to justice. The organization also funds a wide variety of

humanitarian projects, include disaster relief, feeding of the

hungry, and literacy programs. B’nai B’rith furthers its

agenda through an extensive program of speaking and pub-

lication, including the International Jewish M

onthly

.

Further Reading

Cohen, Naomi Werner

. Encounter with Emancipation: The German

Jews in the United States, 1830–1914. Philadelphia: Jewish Pub-

lication Society of America, 1984.

G

rusd, Edward E. B’nai B’

rith: The Story of a Covenant. N

ew York:

Appleton-Century, 1966.

Moore, Deborah Dash. B’nai B’rith and the Challenge of Ethnic Lead-

ership. Albany: State U

niversity of New York Press, 1981.

This is B’nai B’rith. Rev. ed. Washington, D.C.: B’nai B’rith Interna-

tional, 1979.

Border Patrol, U.S.

The U.S. Border Patrol is the uniformed enforcement arm

of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency of the

U.S. C

ITIZENSHIP AND

I

MMIGRATION

S

ERVICES

, in the

D

EPARTMENT OF

H

OMELAND

S

ECURITY

. Prior to 2003, it

was managed by the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZA

-

TION

S

ERVICE

(INS). The Border Patrol was established

in 1924 primarily to control the entry of undocumented

(illegal) aliens. The immediate impetus for its establish-

ment was the dramatic influx of Mexicans, estimated at

some 700,000, due to the Mexican Revolution (1910–17).

Whereas almost all Mexican migrant labor had been tem-

porary before, the revolution permanently displaced thou-

sands who were prepared to stay in the United States.

Although the 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexico border was the focal

point of Border Patrol activity throughout much of the

20th century, the agency was responsible for approximately

250 ports of entry and more than 8,000 miles of land and

sea borders. From the 1960s, it played an increasingly

prominent role in the interception of Caribbean and Cen-

tral American immigrants along the Gulf and Florida

coasts. As the issue of illegal immigration became more

highly politicized in the 1990s, the size and budget of the

agency doubled, most directly through the I

LLEGAL

I

MMI

-

GRATION

R

EFORM AND

I

MMIGRANT

R

ESPONSIBILITY

A

CT

(1996). With increased budgets came more sophisti-

cated technologies, including ground sensors and infrared

tracking equipment, as well as stronger permanent fences

along areas of high crossing. In the 1990s, the Border

Patrol made about 1.5 million arrests annually. Increased

border patrols had little effect on the numbers of illegal

immigrants, however, as they simply turned to more

remote crossing points or paid higher prices to smugglers

for riskier enterprises. In the wake of the S

EPTEMBER

11,

2001, terrorist attacks, Border Patrol duties along the U.S.-

Canadian border were greatly enhanced, with additional

agents and funding allotted under the USA PATRIOT

A

CT

(2001).

See also B

RACERO

P

ROGRAM

; M

EXICAN IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Calavita, Kitty. Inside the State: the Bracero Program, Immigration, and

the I.N.S. New Y

ork: Routledge, 1992.

D

unn, Timothy J. The Militarization of the U.S.-Mexico Border,

1978–1992: Low

-Intensity Conflict Doctrine Comes Home. Austin:

Center for Mexican-American Studies, Univ

ersity of Texas at

Austin, 1996.

Jacobson, David. The Immigration Reader. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell,

1998.

M

itchell, Christopher, ed. Western Hemisphere Immigration and

United S

tates Foreign Policy. University Park: Pennsylvania State

University Pr

ess, 1992.

Perkins, Clifford Alan, and C. L. Sonnichsen. Border Patrol: With the

U.S. I

mmigr

ation Service on the Mexican Boundary, 1910–54. El

Paso: T

exas Western Press, 1978.

Bosnian immigration

Bosnians began to immigrate to North America around

1900, though their numbers remained small until the

BOSNIAN IMMIGRATION 31

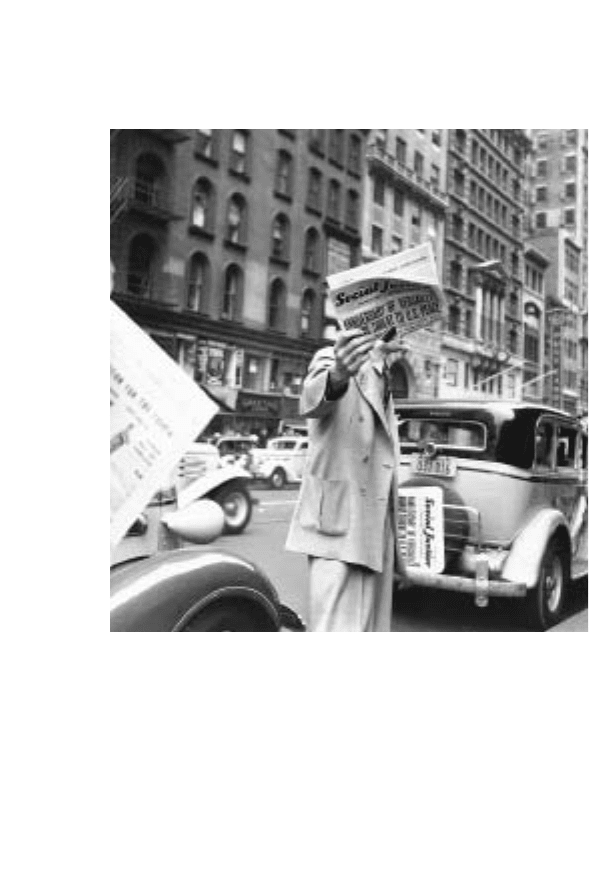

The newspaper Social Justice, founded by Father Charles

Coughlin, railed against the “British-Jewish-Roosevelt

conspiracy.” His strongly anti-Semitic message earned him

30 million radio listeners in the mid-1930s, the largest

radio audience in the world, and pointed to the need for

organizations like B’nai B’rith.

(Photo by Dorothea Lange,

1939/Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USF34-

019817-E])

breakup of Yugoslavia and the resultant civil war in the

early 1990s produced a flood of refugees. In the U.S. 2000

census, of the 328,547 Americans who claimed Yugoslav

descent, about 100,000 were Bosniaks (Bosnians of Mus-

lim descent). In the 2001 Canadian census, 25,665 peo-

ple claimed Bosnian descent. In both countries, the vast

majority of Bosnians were refugees. The earliest Bosnian

immigrants settled in Chicago, Detroit, and other indus-

trial cities of the North. In 2000, more than 75 percent

lived in Chicago, Milwaukee, and Gary, Indiana. The

rapid influx of refugees after 1992 led to Bosnian settle-

ments in New York City; St. Louis, Missouri; St. Peters-

burg, Florida; Chicago; Cleveland, Ohio; and Salt Lake

City, Utah. Bosnian Canadians have gravitated toward

Toronto and southern Ontario, mainly because of devel-

oping economic opportunities there.

The modern country of Bosnia and Herzegovina occu-

pies 19,700 square miles of the western Balkan Peninsula

along the Adriatic Sea between 42 and 45 degrees north

latitude. Serbia and Montenegro lies to the east and the

south, Croatia to the north and west. The land is moun-

tainous with areas of dense forest. In 2002, the popula-

tion was estimated at 3,922,205. The people are ethnically

divided between Bosniaks, who make up 44 percent of the

population; Serbs, 31 percent; and Croats, 17 percent. The

population is similarly divided along religious lines: 43

percent Muslim, 31 percent Orthodox, and 18 percent

Catholic. All groups speak similar Serbo-Croat languages.

Throughout history, Bosnia and Herzegovina have been

ruled both as independent provinces under larger nations

and as a joint province. Bosnia was first ruled by Croatia in

the 10th century, before control passed to Hungary for 200

years. The region came under Turkish rule (Ottoman

Empire) from 1463 until 1878, during which time large

portions of the population were converted to Islam. As

the border regions of the Ottoman Empire became

embroiled in international conflict during the 19th cen-

tury, Catholics from Bosnia generally adopted a Croatian

identity and Orthodox Christians a Serbian one, leaving

Muslims as the only remaining “Bosnians.” When Aus-

tria-Hungary took control of the region in 1878, Bosnia

was united with Herzegovina into a single province. In

1918, Bosnia became a province of Yugoslavia until 1946

when it was again united with Herzegovina as a joint

republic under the new Communist government of Josip

Broz, Marshal Tito. Yugoslavia struggled economically in

the 1980s, leading to increased tensions between the coun-

try’s various ethnic groups and a declaration of Bosnia and

Herzegovina’s independence in 1991. The following year

the question of independence was decided by a referendum

that flung the country into a three-way ethnic civil war.

Bosnian Serbs purged Bosnian Muslims from their terri-

tory, laid siege to the capital of Sarajevo, and embarked on

a campaign of “ethnic cleansing.” In 1994, Muslims and

Croats joined in a confederation to fight the Bosnian Serbs

who had taken control of most of the country. In 1995,

with the help of North Atlantic Treaty Organization

(NATO) air strikes, the Muslim-Croat confederation

regained all but a quarter of the land. NATO stabilization

forces continued into 2004 to occupy the country, which

was governed as a republic under a rotating executive.

It is difficult to arrive at precise figures for Bosnian

immigration. Prior to the 1990s, Bosnian in Yugoslavia was

equated with Muslim, and religious categories were not used

for enumeration of immigrants. Bosnians or

dinarily identi-

fied themselv

es in political terms as Turks or Austro-Hun-

garians prior to World War I, or as Serbs, Croatians, or

Yugoslavs after World War I. Only with the growing sense of

nationalism in the wake of independence did the term

Bosnian (meaning “from Bosnia”) become widely used and

finally incorporated into the recor

d keeping of the U

nited

States and Canada.

The first Bosnian settlers to enter the United States in

significant numbers were peasant farmers from the poorest

areas of Herzegovina. Most settled in Chicago and other

midwestern cities after 1880, where they worked on the new

subway system and in other construction projects. A second

group of Bosnians, implicated by their association with Ser-

bian monarchists or the fascist Croatian Ustasha regime,

immigrated to the United States in the wake of the 1946

Communist takeover of Yugoslavia. They tended to be well

educated and broadly representative of the diverse Muslim

society of Bosnia. The largest group of immigrants came in

the wake of the 1992 war with Serbia, in which 2 million

Bosnians, mostly Bosniaks, were made refugees. From only

15 immigrants in 1992, Bosnian immigration jumped dra-

matically as the fighting wound down, with almost 90,000

being admitted to the United States by 2002.

The first influx of Bosnians into Canada was after

World War II, fleeing from the Communist regime.

Although most were Muslims, they largely considered them-

selves Croatians of Muslim faith. By the late 1980s, there

were about 1,500 Bosnian Muslims in Canada, the major-

ity having come into the country after the mid-1960s, when

Yugoslavia relaxed its emigration policies. In the wake of

the “ethnic cleansing” between 1992 and 1995, thousands

of refugees were admitted to Canada. Of the 25,665

Bosnian immigrants in 2001, 88 percent (22,630) arrived

between 1991 and 2001.

See also A

USTRO

-H

UNGARIAN IMMIGRATION

;C

ROAT

-

IAN IMMIGRATION

; S

ERBIAN IMMIGRATION

; Y

UGOSLAV

IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Friedman, F. The Bosnian Muslims: Denial of a Nation. Boulder, Colo.:

Westvie

w Press, 1996.

“Hope for Bosnian Refugees.” New York Times, March 10, 2000,

p

.

A7.

32 BOSNIAN IMMIGRATION

Malcolm, Noel.Bosnia: A Short History. New York: New York Univer-

sity Press, 1996.

Mertus, Julie, and Jasmina Tesanovic. The Suitcase: Refugee Voices from

Bosnia and C

r

oatia, with Contributions from over Seventy-five

Refugees and Displaced People. Berkeley: University of California

P

r

ess, 1997.

Silber, Laura, and Allan Little. Yugoslavia: D

eath of a N

ation. New

York: Penguin, 1995.

Boston, Massachusetts

The capital of Massachusetts since colonial times, Boston

has also been an important immigrant city since its found-

ing in 1630. Although settled by Puritans, many non-Puri-

tans chose to settle in Boston. By the early 18th century it

had become a diverse commercial, fishing, and shipbuild-

ing center in British North America. Bostonians were

among the most prominent leaders of the patriot movement

of the 1760s and 1770s that led to the A

MERICAN

R

EVO

-

LUTION

and the independence of the United States of

America. As a thriving port of the rapidly developing new

republic, Boston’s population included a large number of

foreign merchants and mariners, but at the turn of the 19th

century, its permanent population was decidedly Anglo-

Saxon. The character of the city was greatly transformed

after 1830 by the influx of Irish settlers escaping economic

hardship and, after 1847, the devastating effects of the

potato famine. The port of Boston, which had not been a

major receiving area for immigrants prior to 1847, took in

20,000 Irish immigrants annually between 1847 and 1854.

By 1860, more than one-third of the population of 136,181

was foreign born, and nearly three-quarters of these were

Irish. After 1880, Boston was second only to New York in

number of immigrants received. It reached its peak in 1907,

taking in 70,164.

Throughout the 19th century, immigrants provided

the backbone for the industrial development of Boston.

Before World War I (1914–18), Boston became the center

of American settlement for the Irish and Albanians, with

substantial communities of Armenians, Greeks, and Ital-

ians. The high percentage of immigrants led to widespread

NATIVISM

and discrimination. Many immigrants never-

theless improved their positions, in part because of their

dominance in the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. By

the 1870s, the police and fire departments were dominated

by the Irish, and by the 1880s, one in four teachers was

Irish. By the early 20th century, second- and third-genera-

tion Irish were moving into positions of prominence in

business, public services, and politics and by the 1940s,

had moved into the economic and political mainstream.

After World War II (1939–45), Barbadians, Brazilians,

Haitians, Hasidic Jews, Soviet Jews, Hondurans, Latvians,

Lithuanians, and Panamanians established substantial

communities in Boston.

Further Reading

Handlin, Oscar. B

oston’s Immigrants: A Study in Acculturation. Rev.

ed. New York: Atheneum, 1968.

Levitt, Peggy. “Transnationalizing Community Development: The

Case of Migration between Boston and the Dominican Repub-

lic.” Non-Profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 26 (1997):

509–526.

O’Connor

,

Thomas H. The Boston Irish: A Political History. B

oston:

Northeastern University Press, 1995.

Stolarik, M. Mark, ed. Forgotten Doors: The Other Ports of Entry to the

United S

tates. P

hiladelphia: Balch I

nstitute Press, 1988.

Thernstrom, Stephen. The Other Bostonians: Poverty and Progress in the

American M

etropolis, 1880–1970. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard

Univ

ersity Press, 1973.

———Poverty and Progress: Social Mobility in a Nineteenth-Century

American C

ity

. Cambridge, Mass.: Har

vard University Press,

1964.

Bracero Program

Bracero, the Spanish word for “manual laborer,” is the name

given to “temporary” Mexican laborers who entered the

United States under congressional exemptions from other-

wise restrictive immigration legislation. More specifically,

the Bracero Program was the informal name given to the

Emergency Farm Labor Program initiated in 1942 and

extended until 1964 that enabled Mexican farmworkers to

legally enter the United States with certain protections in

order to ensure the availability of low-cost agricultural labor.

At the same time that the Mexican government selected the

allotted quota of workers for the Bracero Program—averag-

ing almost 300,000 annually during the 1950s—a similar

number were entering illegally and became commonly

known as “wetbacks” (many having waded across the Rio

Grande). Together, the legal and illegal immigrants of this

period made Mexico the predominant country sending

immigrants to the United States.

Mexican laborers first came to the United States in sig-

nificant numbers in the first decade of the 20th century,

replacing the excluded Chinese and Japanese laborers.

Wartime demands for labor during World War I (1914–18)

coupled with the labor needs of southwestern agriculturalists,

encouraged the U.S. Congress to exempt Mexicans as tem-

porary workers from otherwise restrictive immigrant legisla-

tion. As a result, almost 80,000 Mexicans were admitted

between the creation of a “temporary” farmworkers’ program

in 1917 and its termination in 1922. Fewer than half of the

workers returned to Mexico. Linking with networks that orga-

nized and transported the Mexican laborers, workers contin-

ued to enter the United States throughout the 1920s, with

459,000 officially recorded. Although there were no official

limits on immigration from the Western Hemisphere, many

Mexicans chose to bypass the official process, which since

1917 had included a literacy test; the actual number of Mex-

ican immigrants was therefore much higher.

BRACERO PROGRAM 33