Pike Robert, Neal Bill. Corporate finance and investment: decisions and strategy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

.

Chapter 8 Analysing investment risk 205

Table 8.5 UMK cost structure

Unit data £ £

Selling price 20

Less: Materials (6)

Labour (5)

Variable costs (1)

(12)

Contribution 8

Annual sales (units) 12,000

Total contribution 96,000

Less: Additional fixed costs (20,000)

Annual net cash flow 76,000

Present value (4 years at 10%)

240,920

Less: Capital outlay (200,000)

Net present value 40,920

Annual cash receipts

The break-even position is reached when annual cash receipts multiplied by the annu-

ity factor equal the investment outlay. The break-even cash flow is therefore the invest-

ment outlay divided by the annuity factor:

This is a percentage fall of

Annual fixed costs could increase by the same absolute amount of £12,909, or

Annual sales volume the break-even annual contribution is £63,091 £20,000 £83,091.

Sales volume required to break even is £83,091/£8 10,386, which is a percentage

decline of

Selling price can fall by:

a decline of

Variable costs per unit can rise by a similar amount:

Continued

£1.07

£12

100 8.9%

£1.07

£20

100 5.4%

£96,000 £83,091

12,000

£1.07 per unit

12,000 10,386

12,000

100 13.5%

£12,909

£20,000

100 64.5%

£76,000 £63,091

£76,000

17.0%

£200,000

3.17

£63,091

76,000 3.17

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 205

.

206 Part III Investment risk and return

New risks put scenario planning in favour

FT

Who could have predicted the

horrific events of September 11,

2001? A 1999 US congressional

commission led by former sena-

tors Gary Hart and Warren

Rudman came close. It warned

that the US was ‘increasingly vul-

nerable to attack on our home-

land’ and that ‘rapid advances in

information and biotechnologies

will create new vulnerabilities’.

But perhaps more important

than the commission’s prophetic

messages was its approach.

Instead of forecasting a specific

future, it set out a collection of

possible attack scenarios. It then

evaluated national security by

analysing possible policies to pre-

pare for, or respond to them.

This approach – known as

scenario planning – has gained

renewed popularity among pub-

lic and private decision-makers.

In January this year, the New

England Journal of Medicine pub-

lished a scenario planning analysis

on whether US health workers or

the whole nation should be vacci-

nated against smallpox to counter

the threat of bio-terrorism. Presi-

dent George W. Bush decided to

inoculate 500,000 military person-

nel and 439,000 health workers.

Scenario planners face three

challenges. The first is construct-

ing meaningful scenarios. This

requires expert analysis of the

factors that affect the outcomes. A

second challenge is determining

the likelihoods of the scenarios.

Finally, planners must decide

on a good criterion for selecting

strategies. Most individuals and

institutions are risk-averse: they

value an uncertain reward at a

level significantly below the aver-

age level the reward in fact reach-

es. Strategies with higher average

pay-offs often entail greater risks.

Hence, scenario planning often

involves analysing the reward at

different levels of risk – much as

is done in financial planning.

What explains the recent inter-

est in scenario planning? For one

thing, we live in turbulent times.

Terrorism, political instability

and threats of war make scenar-

ios of extreme price fluctuations

in commodity and energy mar-

kets more likely. Severe acute res-

piratory syndrome, ‘mad cow

disease’ and foot-and-mouth dis-

ease have rekindled awareness of

the natural biological threats we

face. Accounting scandals force us

to second-guess what used to be

considered accurate information

about suppliers and customers. In

short, companies face far greater

risks than before. Indeed, when

Mattel used scenario planning to

formulate its 2002 strategy, it

considered scenarios with several

big customers (such as Kmart,

FAO and eToys) going bankrupt

and others (Wal-Mart) starting to

make their own toys.

Source: Awi Federgruen and Garrett Van Ryzin,

Financial Times, 19 August 2003, p. 11.

Sensitivity analysis, as applied in the above example, discloses that selling price and

variable costs are the two most critical variables in the investment decision. The deci-

sion-maker must then determine (subjectively or objectively) the probabilities of such

changes occurring, and whether he or she is prepared to accept the risks.

■ Scenario analysis

Sensitivity analysis considers the effects of changes in key variables only one at a time.

It does not ask the question: ‘How bad could the project look?’ Enthusiastic managers

can sometimes get carried away with the most likely outcomes and forget just what

might happen if critical assumptions – such as the state of the economy or competitors’

reactions – are unrealistic. Scenario analysis seeks to establish ‘worst’ and ‘best’ scenar-

ios, so that the whole range of possible outcomes can be considered. It encourages ‘con-

tingent thinking’, describing the future by a collection of possible eventualities.

Discount rate

The break-even annuity factor is £200,000/£76,000=2.63. Reference to the present value

annuity tables for four years shows that 2.63 corresponds to an IRR of 19 per cent. The error

in cost of capital calculation could be as much as nine percentage points before it affects the

decision advice.

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 206

.

Chapter 8 Analysing investment risk 207

Market factors Investment factors Cost factors

Market size Investment outlay Variable costs

Market growth rate Project life Fixed costs

Selling price of product Residual value

Market share captured by the firm

Self-assessment activity 8.5

What do you understand by Monte Carlo simulation? When might it be useful in capital

budgeting?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

■ Simulation analysis

An extension of scenario analysis is simulation analysis. Monte Carlo simulation is an

operations research technique with a variety of business applications. The computer

generates hundreds of possible combinations of variables according to a pre-specified

probability distribution. Each scenario gives rise to an NPV outcome which, along with

other NPVs, produces a probability distribution of outcomes.

One of the first writers to apply the simulation approach to risky investments was

Hertz (1964), who described the approach adopted by his consultancy firm in evaluat-

ing a major expansion of the processing plant of an industrial chemical producer. This

involved constructing a mathematical model that captured the essential characteristics

of the investment proposal throughout its life as it encountered random events.

A simulation model might consider the following variables, which are subject to

random variation.

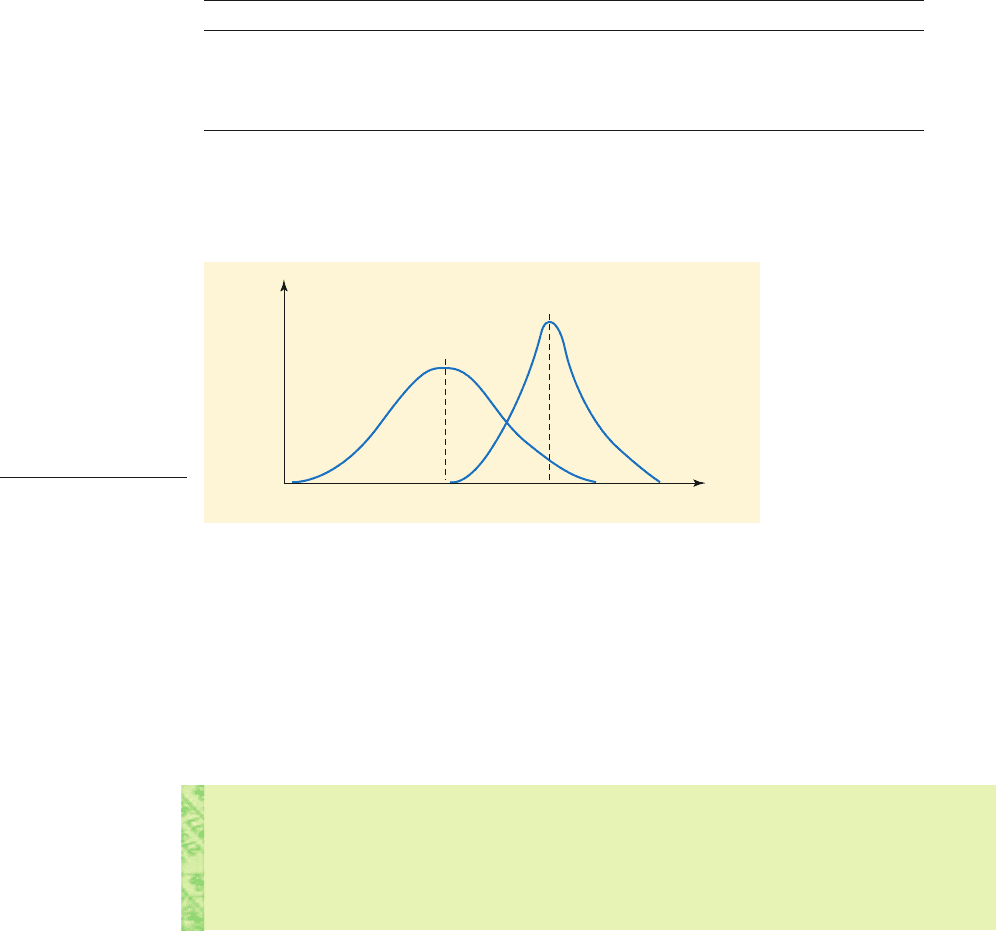

Comparison is then possible between mutually exclusive projects whose NPV prob-

ability distributions have been calculated in this manner (Figure 8.6). It will be observed

that project A, with a higher expected NPV and lower risk, is preferable to project B.

Monte Carlo simulation

Method for calculating the

probability distribution of

possible outcomes

B

A

NPV

Frequency

0

Figure 8.6

Simulated probability

distributions

In practice, few companies use this risk analysis approach, for the following reasons:

1 The simple model described above assumes that the economic factors are unrelated.

Clearly, many of them (e.g. market share and selling price) are statistically interde-

pendent. To the extent that interdependency exists among variables, it must be speci-

fied. Such interrelationships are not always clear and are frequently complex to model.

2 Managers are required to specify probability distributions for the exogenous vari-

ables. Few managers are able or willing to accept the demands required by the sim-

ulation approach.

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 207

.

208 Part III Investment risk and return

Two approaches are commonly used to incorporate risk within the NPV formula.

■ Certainty equivalent method

This conceptually appealing approach permits adjustment for risk by incorporating the

decision-maker’s risk attitude into the capital investment decision. The certainty equiv-

alent method adjusts the numerator in the net present value calculation by multiplying

the expected annual cash flows by a certainty equivalent coefficient. The revised for-

mula becomes:

Certainty equivalent method

where: is the expected net present value; is the certainty equivalent coefficient,

which reflect’s management’s risk attitude; is the expected cash flow in period t; i is

the riskless rate of interest; n is the project’s life; and is the initial cash outlay.

The numerator represents the figure that management would be willing to

receive as a certain sum each year in place of the uncertain annual cash flow offered

by the project. The greater is management’s aversion to risk, the nearer the certainty

equivalent coefficient is to zero. Where projects are of normal risk for the business, and

the cost of capital and risk-free rate of interest are known, it is possible to determine

the certainty equivalent coefficient.

Example

Calculate the certainty equivalent coefficient for a normal risk project with a one-year

life and an expected cash flow of £5,000 receivable at the end of the year. Shareholders

require a return of 12 per cent for projects of this degree of risk and the risk-free rate of

interest is 6 per cent.

The present value of the project, excluding the initial cost and using the 12 per cent

discount rate, is:

Using the present value and substituting the risk-free interest rate for the cost of

capital, we obtain the certainty equivalent coefficient:

The management is, therefore, indifferent as to whether it receives an uncertain

cash flow one year hence of £5,000 or a certain cash flow of £4,732 (i.e. £5,000 0.9464).

■ Risk-adjusted discount rate

Whereas the certainty equivalent approach adjusted the numerator in the NPV formula,

the risk-adjusted discount rate adjusts the denominator:

0.9464

a

1£4,4642

11.062

£5,000

a £5,000

1 0.06

£4,464

PV

£5,000

1 0.12

£4,464

1aX

t

2

I

o

X

t

aNPV

NPV

a

N

t 1

aX

t

11 i2

t

I

o

8.7 ADJUSTING THE NPV FORMULA FOR RISK

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 208

.

Chapter 8 Analysing investment risk 209

Adjusting the discount rate: Chox-Box Ltd

Chox-Box Ltd is a manufacturer of confectionery currently appraising a proposal to launch

a new product that has had very little pre-launch testing. It is estimated that this proposal

will produce annual cash flows in the region of £100,000 for the next five years, after which

product profitability declines sharply. As the proposal is seen as a high-risk venture, a 12

per cent risk premium is incorporated in the discount rate. The risk-adjusted cash flow,

before discounting at the risk-free discount rate, is therefore £89,286 in Year 1 (£100,000/1.12),

falling to £56,742 in Year 5 (£100,000/1.12

5

).

To what extent does this method reflect the actual riskiness of the annual cash flows for

Years 1 and 5? Arguably, the greatest uncertainty surrounds the initial launch period. Once

the initial market penetration and subsequent repeat orders are known, the subsequent

sales are relatively easy to forecast. Thus, for Chox-Box, a single risk-adjusted discount rate

is a poor proxy for the impact of risk on value over the project’s life, because risk does not

increase exponentially with the passage of time, and, in some cases, actually declines over

time. The Eurotunnel project provides another illustration of this. By far the greatest risks

were in the initial tunnelling and development phases.

A deeper understanding of the relationship between the certainty equivalent and risk-

adjusted discount rate approaches may be gained by reading the appendix to this chapter.

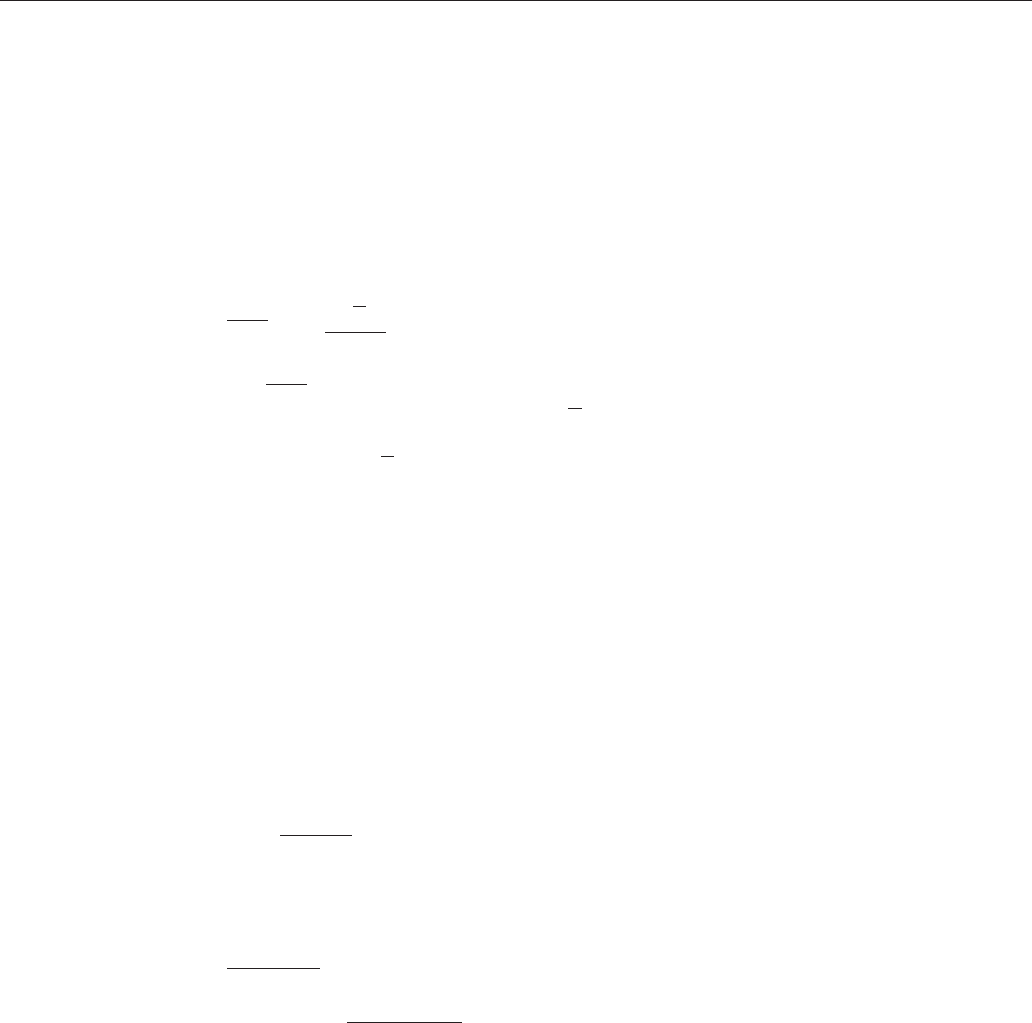

246 810

Time (years)

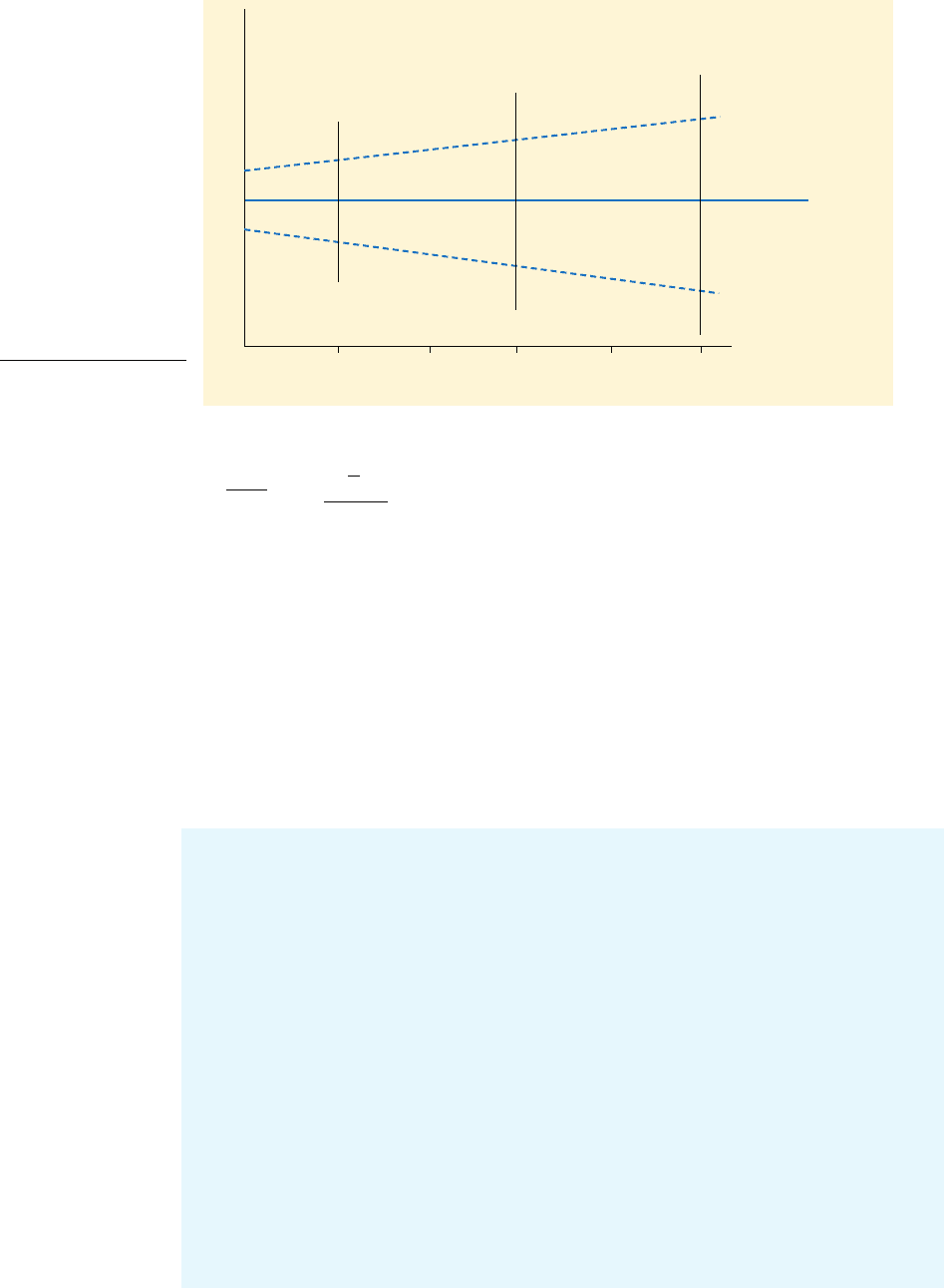

Expected

cash flow

Cash-flow (£)

Figure 8.7

How risk is assumed to

increase over time

Risk-adjusted discount rate method

where k is the risk-adjusted rate based on the perceived degree of project risk.

The higher the perceived riskiness of a project, the greater the risk premium to be added to

the risk-free interest rate. This results in a higher discount rate and, hence, a lower net

present value.

Although this approach has a certain intuitive appeal, its relevance depends very

much on how risk is perceived to change over time. The risk-adjusted discount rate

involves the impact of the risk premium growing over time at an exponential rate, imply-

ing that the riskiness of the project’s cash flow also increases over time. Figure 8.7 demon-

strates this point. Although the expected cash flow from a project may be constant over

its ten-year life, the riskiness associated with the cash flows increases with time. However,

if risk did not increase with time, the risk-adjusted discount rate would be inappropriate.

NPV

a

N

t 1

X

t

11 k2

t

I

o

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 209

.

210 Part III Investment risk and return

Table 8.6

Risk analysis in 100

large UK firms

1975 (%) 1980 (%) 1986 (%) 1992 (%) 1997 (%)

Sensitivity analysis 28 42 71 86 89

Best/worst case analysis n.a. n.a. 93 95 n.a.

Reduced payback period 25 30 61 59 11

Risk-adjusted rate 37 41 61 64 50

Probability analysis 9 10 40 47 42

Beta analysis – – 16 20 5

Source: Pike (1996), Arnold and Hatzopoulos (2000)

The big gamble: Airbus rolls out its new weapon in its battle with Boeing

The biggest bet placed by Europe’s aerospace industry was

officially launched in January 2005. The Airbus A380 – a

twin-decked behemoth with seats for 555 passengers – was

rolled out in Toulouse and gives the company a complete

range of models to challenge Boeing, ending the lucrative

monopoly Boeing has had in the very large aircraft market

for 35 years.

Noel Forgeard, Airbus chief executive, says the company

had made a ‘successful metamorphosis to a world leader’.

He claims the group is almost twice as profitable as

Boeing’s commercial airplanes division, helped by a ‘huge,

relentless effort to reduce unit cost and grow our produc-

tivity: it is the reason why we can gain market share and

grow profitably.’

Boeing has certainly looked increasingly vulnerable. The

group’s critics say its long years of success led to compla-

cency and it allowed the pace of product innovation to

slow as it prioritised short-term earnings over investment.

‘Boeing has struggled with the development work needed

to take the company into the 21st century,’ says Tim

Clark, president of Emirates, the Dubai-based airline that

is one of the world’s most important buyers of long-haul

aircraft and will be the biggest operator of the Airbus

A380.

Airbus’s A380 ‘will change the game for long-haul air-

lines and airports,’ says Chris Avery, aviation analyst at JP

Morgan. ‘With operating costs 15 per cent below the

B747-400, we believe A380 operations will have an advan-

tage on long-haul services in markets between Europe and

Asia, across the Pacific and across the Atlantic.’ Boeing,

however, thinks the A380 is a white elephant, designed for

a world that no longer needs aircraft of such great size.

Airbus has 149 orders so far, still short of the 250 that it

estimates are needed to give a profit. The $11 billion

investment of public and private money is a huge gamble.

Boeing and Airbus agree that air traffic over the next 20

years is expected to increase annually on average by about

5 per cent. But they differ greatly on how airlines will

accommodate that. Boeing’s vision is based on the ‘frag-

mentation’ of aviation markets, reflecting passengers’ pref-

erence for more point-to-point, non-stop services and more

frequent services instead of being routed to destinations via

connecting hubs. Airbus accepts that fragmentation, but it

also expects consolidation on the main trunk routes.

MINI CASE

8.8 RISK ANALYSIS IN PRACTICE

To what extent do companies employ the techniques discussed in this chapter? Table 8.6

shows changes over the past twenty-five years.

Sensitivity analysis and best/worst case (or scenario) analysis are conducted in

almost all larger UK companies. Approximately one half of larger firms adjust the dis-

count rate for risk. Less common, however, are techniques requiring managers to

assign probabilities to possible outcomes; managers prefer to assess the likelihood of

outcomes in a more subjective manner. Finally, there is little real evidence that Beta

analysis (based on the Capital Asset Pricing Model and discussed in Chapter 10) is

used extensively in industry.

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 210

.

Chapter 8 Analysing investment risk 211

Airbus seems to be winning the argument. In recent

years, it has won over some operators that previously used

only Boeing aircraft. But Airbus still has plenty to prove. In

Japan, Boeing reigns supreme. There, the government and

the aerospace industry are backing Boeing’s 7E7.

Another challenge is the weakness of the dollar against

the euro. This has the potential to undermine its long-term

competitiveness. For most of 2005 and 2006 Airbus is pro-

tected, having hedged about $40 billion of revenues at

around It has also taken the precaution of pricing

most of its purchases in dollars – even in Europe –

thereby transferring exchange risk to suppliers. Gerald Blanc,

Airbus executive vice-president operations, warned, ‘This will

probably impair our ability to invest as much in research and

development as we have done so far.’

A third challenge is Airbus’s ability to show it will not be

thrown off course by the change of management at the

top. The tussle for supremacy in managing Airbus between

the parent company’s dominant French and German share-

holders means that it is currently without a chief executive

at a time when the A380 project is about to enter the cru-

cial phase of flight testing, certification and the build-up of

production before the first delivery in 2006.

Source: Based on Financial Times, 17 January 2005.

Required

Identify the strategic and financial risks in the Airbus

A380 project and suggest how they should be assessed

and managed.

;1>$1.

Risk is an important element in virtually all investment decisions. Because most peo-

ple in business are risk-averse, the identification, measurement and, where possible,

reduction of risk should be a central feature in the decision-making process. The evi-

dence suggests that firms are increasingly conducting risk analysis. This does not

mean that the risk dimension is totally ignored by other firms; rather, they choose to

handle project risk by less objective methods such as experience, feel or intuition.

We have defined what is meant by risk and examined a variety of ways of measur-

ing it. The probability distribution, giving the probability of occurrence of each possi-

ble outcome following an investment decision, is the concept underlying most of the

methods discussed. Measures of risk, such as the standard deviation, indicate the

extent to which actual outcomes are likely to vary from the expected value.

Key points

■ The expected NPV, although useful, does not show the whole picture. We need to

understand managers’ attitudes to risk and to estimate the degree of project risk.

■ Three types of risk are relevant in capital budgeting: project risk in isolation, the

project’s impact on corporate risk and its impact on market risk. The last two are

addressed more fully in the following two chapters.

■ The standard deviation, semi-variance and coefficient of variation each measure, in

slightly different ways, project risk.

■ Sensitivity analysis and scenario analysis are used to locate and assess the potential

impact of risk on project performance. Simulation is a more sophisticated approach,

which captures the essential characteristics of the investment that are subject to

uncertainty.

■ The NPV formula can be adjusted to consider risk. Adjustment of the cash flows

is achieved by the certainty equivalent method. The risk-adjusted discount rate

increases the risk premium for higher-risk projects.

SUMMARY

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 211

.

212 Part III Investment risk and return

Further reading

A fuller treatment of risk is found in Levy and Sarnat (1994). Useful research studies on the use

of risk analysis are given in Pike (1988, 1996), Pike and Ho (1991), Mao and Helliwell (1969) and

Bierman and Hass (1973).

For simplicity, we have so far assumed single-period investments and conveniently

ignored the fact that investments are typically multi-period. As risk is to be specifical-

ly evaluated, cash flows should be discounted at the risk-free rate of interest, reflect-

ing only the time-value of money. To include a risk premium within the discount rate,

when risk is already considered separately, amounts to double-counting and typically

understates the true net present value. The expected NPV of an investment project is

found by summing the present values of the expected net cash flows and deducting

the initial investment outlay. Thus, for a two-year investment proposal:

where is the expected NPV, is the expected value of net cash flow in Year 1,

is the expected value of net cash flow in Year 2, is the cash investment outlay and

i is the risk-free rate of interest.

A major problem in calculating the standard deviation of a project’s NPVs is that

the cash flows in one period are typically dependent, to some degree, on the cash flows

of earlier periods. Assuming for the present that cash flows for our two-period project

are statistically independent, the total variance of the NPV is equal to the discounted

sum of the annual variances.

For example, the Bronson project, with a two-year life, has an initial cost of £500 and

the possible payoffs and probabilities outlined in Table 8.7. Applying the standard

deviation and expected value formulae already discussed, we obtain an expected NPV

of £268 and standard deviation of £206.

Assuming a risk-free discount rate of 10 per cent, the expected NPV is:

NPV

300

11.102

600

11.102

2

500 £268

I

o

X

2

X

1

NPV

NPV

X

1

1 i

X

2

11 i2

2

I

o

APPENDIX

MULTI-PERIOD CASH FLOWS AND RISK

Table 8.7

Bronson project pay-

offs with independent

cash flows

Probability Year 1 cash flow (£) Year 2 cash flow (£)

0.1 100 200

0.2 200 400

0.4 300 600

0.2 400 800

0.1 500 1,000

Expected value £300 £600

Standard deviation £109 £219

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 212

.

Chapter 8 Analysing investment risk 213

The standard deviation of the entire proposal is found by discounting the annual

variances to their present values, applying the equation:

In our simple case, this is:

The project therefore offers an expected NPV of £268 and a standard deviation of

£206.

■ Perfectly correlated cash flows

At the other extreme from the independence assumption is the assumption that the

cash flows in one year are entirely dependent upon the cash flows achieved in previ-

ous periods. When this is the case, successive cash flows are said to be perfectly cor-

related. Any deviation in one year from forecast directly affects the accuracy of

subsequent forecasts. The effect is that, over time, the standard deviation of the prob-

ability distribution of net present values increases. The standard deviation of a stream

of cash flows perfectly correlated over time is:

Returning to the example in Table 8.7, but assuming perfect correlation of cash

flows over time, the standard deviation for the project is:

Thus the risk associated with this project is £280, assuming perfect correlation,

which is higher than that for independent cash flows. Obviously, this difference would

be considerably greater for longer-lived projects.

In reality, few projects are either independent or perfectly correlated over time. The

standard deviation lies somewhere between the two. It will be based on the formula

for the independence case, but with an additional term for the covariance between

annual cash flows.

■ Interpreting results

While decision-makers are interested to know the degree of risk associated with a

given project, their fundamental concern is whether the project will produce a positive

net present value. Risk analysis can go some way to answering this question. If a pro-

ject’s probability distribution of expected NPVs is approximately normal, we can esti-

mate the probability of failing to achieve at least zero NPV. In the previous example,

the expected NPV was £268. This is standardised by dividing it by the standard devi-

ation using the formula:

Z

X NPV

s

£280

s

£109

1.1

£219

11.12

2

s

a

N

t 1

s

t

11 i2

t

s

B

s

1

2

11 i2

2

s

2

2

11 i2

4

B

12,000

11.12

2

48,000

11.12

4

£206

s

B

a

N

t 1

s

t

2

11 i2

2

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 213

.

214 Part III Investment risk and return

where X in this case is zero and Z is the number of standardised units. Thus, in the

case of the independent cash flow assumption, we have:

Reference to normal distribution tables reveals that there is a 0.0968 probability that

the NPV will be zero or less. Accordingly there must be a or 90.32 per cent

probability of the project producing an NPV in excess of zero.

It is probably unnecessary to attempt to measure the standard deviation for every

project. Even the larger European companies tend to use probability analysis sparingly

in capital project analysis. Unless cash flow forecasting is wildly optimistic, or the

future economic conditions underlying all investments are far worse than anticipated,

the bad news from one project should be compensated by good news from another

project.

Sometimes, however, a project is of such great importance that its failure could

threaten the very survival of the business. In such a case, management should be fully

aware of the scale of its exposure to loss and the probability of occurrence.

■ Probability of failure: Microloft Ltd

Microloft Ltd, a local family-controlled company specialising in attic conversions, is

currently considering investing in a major expansion giving wider geographical cov-

erage. The NPV from the project is expected to be £330,000 with a standard deviation

of £300,000. Should the project fail (perhaps because of the reaction by major competi-

tors), the company could afford to lose £210,000 before the bank manager ‘pulled the

plug’ and put in the receiver. What is the probability that this new project could put

Microloft out of business?

We need to find the value of Z where X is the worst NPV outcome that Microloft

could tolerate:

Assuming the outcomes are normally distributed, probability tables will show a 3.6

per cent chance of failure from accepting the project. A family-controlled business, like

Microloft, may decide that even this relatively small chance of sending the company

on to the rocks is more important than the attractive returns expected from the project.

£210 £330

£330

1.8

Z

X NPV

s

11 0.09682

1.30 standardised units

Z

0 £268

£206

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 214