Pike Robert, Neal Bill. Corporate finance and investment: decisions and strategy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

.

Analysing investment risk

8

Learning objectives

The main learning objectives are the following:

■ To understand how uncertainty affects investment decisions.

■ To explore managers’ risk attitudes.

■ To appreciate the levels at which risk can be viewed.

■ To be able to measure the expected NPV and its variability.

■ To appreciate the main risk-handling techniques and apply them to capital budgeting problems.

Eurotunnel investors discover a black hole

In 1802, Napoleon turned down French mining engi-

neer Matthieu Favier’s proposal for a Channel tunnel,

rising in the centre to a man-made island allowing

for a change of horses for the stage-coach traffic.

Many other schemes were subsequently rejected

until, in 1986, the Anglo-French Treaty was signed,

authorising the construction, financing and operation

of a twin rail tunnel system by Eurotunnel. The com-

pany is, effectively, a one-project business.

The preliminary prospectus provided forecasts

upon which expected returns and sensitivities could

be prepared. Potential investors and lenders were

asked to invest in a highly risky venture that would

not pay a dividend for at least eight years and where

the expected annual return was around 14 per cent.

The Economist commented at the time that the

Tunnel was ‘a hole in the ground that will either make

or lose a fortune’ for its investors. Throughout its

much-publicised history, Eurotunnel has struggled to

raise the necessary finances. The project’s construction

costs have more than doubled the original estimate,

while delays in completion and late delivery of trains

have held up revenue growth. On top of this, a major

fire on the supposedly safe freight carriages put it out

of operation and dented public confidence.

By 2000, things were looking a little better. The

chairman announced that the first dividend was

expected in 2006. However, closer questioning

revealed that this was the ‘upper case scenario’. In

the ‘lower case scenario’ dividend payments do not

begin until 2010. In 2005 the company is looking to

set up a rescue deal to pay for the interest charges

on the 6.4 billion it owes to 122 banks.

Those first investors who took a risk on either

making or losing a fortune saw Eurotunnel’s share

price plummet from 900p to 20p, and may have to

wait a quarter of a century before they receive their

first dividend! To the public, Eurotunnel may be a

hole in the ground, but to original investors it is a

massive hole in their pockets.

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 195

.

196 Part III Investment risk and return

Self-assessment activity 8.1

Why is risk assessment important in making capital investment decisions?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

8.1 INTRODUCTION

The Channel Tunnel is one of many cases where investment decisions turn out to be far

riskier than originally envisaged. The finance director of a major UK manufacturer for

the motor industry remarked, ‘We know that, on average, one in five large capital proj-

ects flops. The problem is: we have no idea beforehand which one!’

Stepping into the unknown – which is what investment decision-making effective-

ly is – means that mistakes will surely occur. Entrepreneurs, on average, have nine

failures for each major success. Similarly, on average, nine empty oil wells are drilled

before a successful oil strike. Sir Richard Branson, head of Virgin Atlantic, once said,

‘the safest way to became a millionaire is to start as a billionaire and invest in the air-

line industry.’

This does not mean that managers can do nothing about project failures. In this and

subsequent chapters, we examine how project risk is assessed and controlled. The var-

ious forms of risk are defined and the main statistical methods for measuring project

risk within single-period and multi-period frameworks are described. A variety of risk

analysis techniques will then be discussed. These fall conveniently into methods intend-

ed to describe risk and methods incorporating project riskiness within the net present

value formula. The chapter concludes by examining the extent to which the methods

discussed are used in business organisations.

■ Defining terms

At the outset, we need to clarify our terms:

■ Certainty. Perfect certainty arises when expectations are single-valued: that is, a par-

ticular outcome will arise rather than a range of outcomes. Is there such a thing as

an investment with certain payoffs? Probably not, but some investments come fair-

ly close. For example, an investment in three-month Treasury Bills will, subject to

the Bank of England keeping its promise, provide a precise return on redemption.

■ Risk and uncertainty. Although used interchangeably in everyday parlance, these

terms are not quite the same. Risk refers to the set of unique consequences for a

given decision that can be assigned probabilities, while uncertainty implies that it

is not fully possible to identify outcomes or to assign probabilities. Perhaps the

worst forms of uncertainty are the ‘unknown unknowns’ – outcomes from events

that we did not even consider.

The most obvious example of risk is the 50 per cent chance of obtaining a ‘head’ from

tossing a coin. For most investment decisions, however, empirical experience is hard to

find. Managers are forced to estimate probabilities where objective statistical evidence is

not available. Nevertheless, a manager with little prior experience of launching a partic-

ular product in a new market can still subjectively assess the risks involved based on the

information he or she has. Because subjective probabilities may be applied to investment

decisions in a manner similar to objective probabilities, the distinction between risk and

uncertainty is not critical in practice, and the two terms are often used interchangeably.

Investment decisions are only as good as the information upon which they rest.

Relevant and useful information is central in projecting the degree of risk surrounding

future economic events and in selecting the best investment option.

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 196

.

Chapter 8 Analysing investment risk 197

Table 8.1

Betterway plc: expected

net present values

NPV outcomes Weighted outcomes

Investment (£) Probability (£)

A 9,000 1 9,000

10,000 0.2 2,000

B 10,000 0.5 5,000

20,000 0.3 6,000

1.0 9,000

50,000 0.2 11,000

C 10,000 0.5 5,000

50,000 0.3 15,000

1.0 9,000

ENPV

ENPV

8.2 EXPECTED NET PRESENT VALUE (ENPV): BETTERWAY PLC

To what extent is the net present value criterion relevant in the selection of risky invest-

ments? Consider the case of Betterway plc, contemplating three options with very dif-

ferent degrees of risk. The distribution of possible outcomes for these options is given

in Table 8.1. Notice that A’s cash flow is totally certain.

Clearly, while the NPV criterion is appropriate for investment option A, where the

cash flows are certain, it is no longer appropriate for the risky investment options B

and C, each with three possible outcomes. The whole range of possible outcomes may

be considered by obtaining the expected net present value (ENPV), which is the mean

of the NPV distribution when weighted by the probabilities of occurrence. The ENPV

is given by the equation:

where is the expected value of event X, is the possible outcome i from event X,

is the probability of outcome i occurring and N is the number of possible outcomes.

The NPV rule may then be applied by selecting projects offering the highest expect-

ed net present value. In our example, all three options offer the same expected NPV of

£9,000. Should the management of Betterway view all three as equally attractive? The

answer to this question lies in their attitudes towards risk, for while the expected out-

comes are the same, the possible outcomes vary considerably. Thus, although the expect-

ed NPV criterion provides a single measure of profitability, which may be applied to

risky investments, it does not, by itself, provide an acceptable decision criterion.

p

i

X

i

X

X

a

N

i 1

p

i

X

i

expected net present value

The average of the range of

possible NPVs weighted by

their probability of occurrence

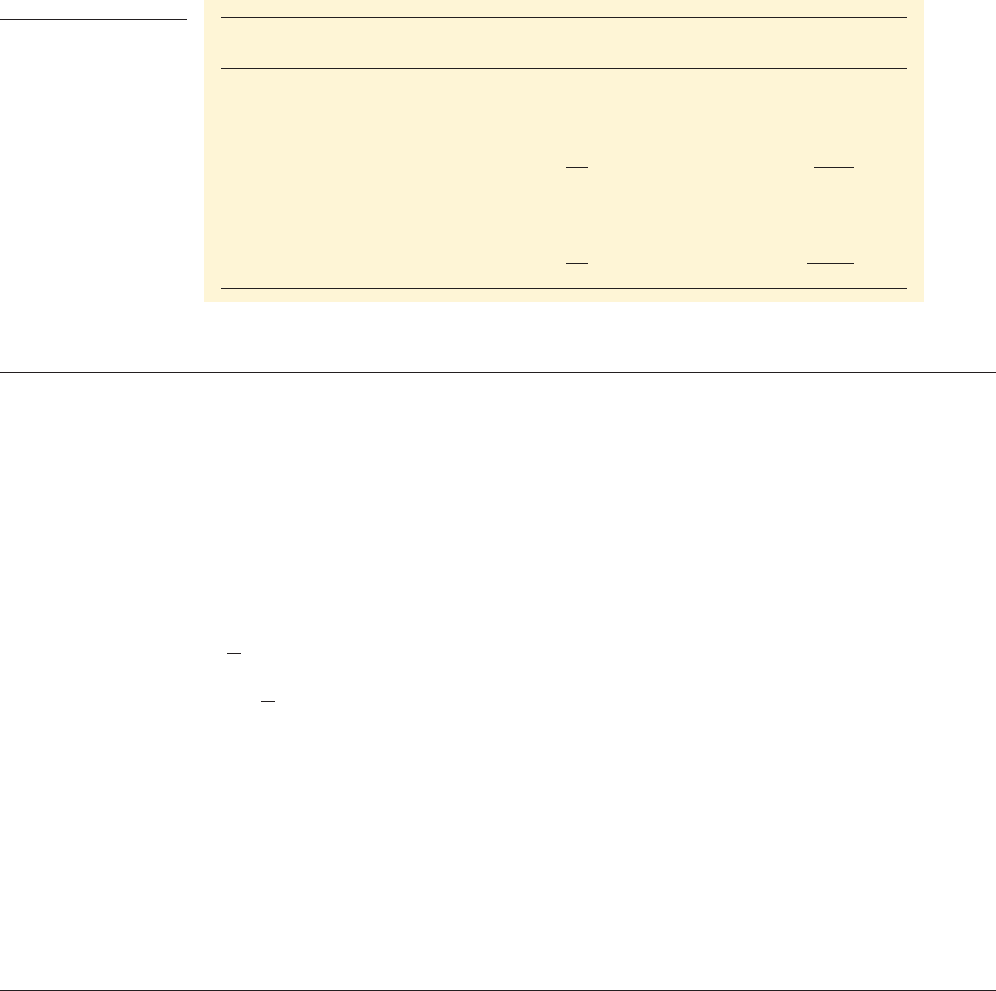

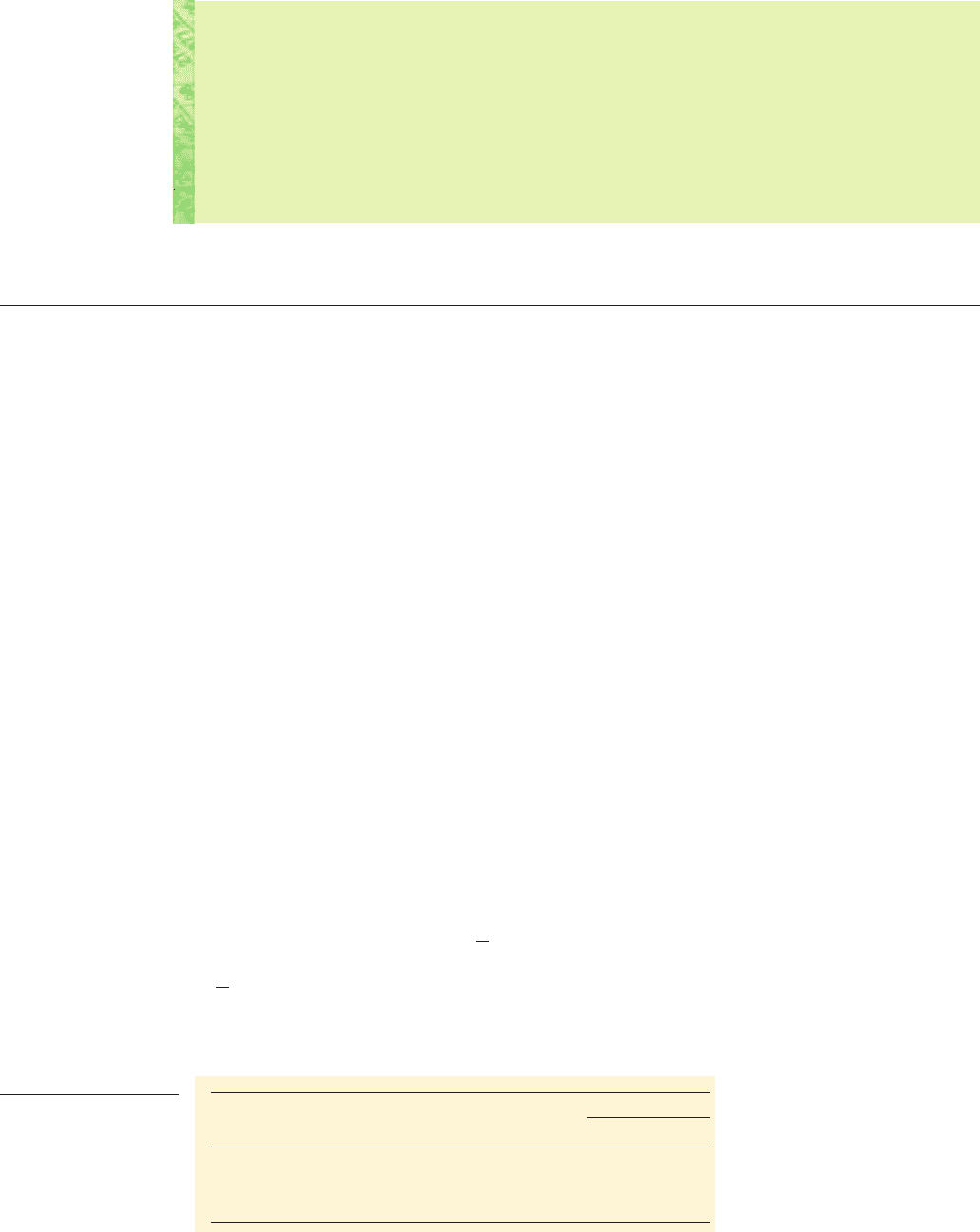

8.3 ATTITUDES TO RISK

Business managers prefer less risk to more risk for a given return. In other words, they

are risk-averse. In general, a business manager derives less utility, or satisfaction, from

gaining an additional £1,000 than he or she forgoes in losing £1,000. This is based on the

concept of diminishing marginal utility, which holds that, as wealth increases, marginal

utility declines at an increasing rate. Thus the utility function for risk-averse managers

is concave, as shown in Figure 8.1. As long as the utility function of the decision-maker

can be specified, this approach may be applied in reaching investment decisions.

■ Example: Carefree plc’s utility function

Mike Cool, the managing director of Carefree plc, a business with a current market

value of £30 million, has an opportunity to relocate its premises. It is estimated that

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 197

.

198 Part III Investment risk and return

Risk-indifferent

Risk-taker

Risk-averter

Utility

Profit or wealth

Figure 8.1

Risk profiles

0102030 42

Wealth (£m)

Utility

∆

U

F

∆

U

A

Figure 8.2

Risk-averse investor’s

utility function

there is a 50 per cent probability of increasing its value by £12 million and a similar

probability that its value will fall by £10 million. The owner’s utility function is outlined

in Figure 8.2. The concave slope shows that the owner is risk-averse. The gain in utili-

ty as a result of the favourable outcome of £42 million, is less than the fall in util-

ity resulting from the adverse outcome of only £20 million.

The conclusion is that, although the investment proposal offers £1 million expected

additional wealth (i.e. 0.5 £12 m 0.5 (£10 m)), the project should not be under-

taken because total expected utility would fall if the factory were relocated.

While decision-making based upon the expected utility criterion is conceptually

sound, it has serious practical drawbacks. Mike Cool may recognise that he is risk-

averse, but is unable to define, with any degree of accuracy, the shape of his utility func-

tion. This becomes even more complicated in organisations where ownership and

management are separated, as is the case for most companies. Here, the agency problem

discussed in Chapter 1 arises. Thus, while utility analysis provides a useful insight into

the problem of risk, it does not provide us with operational decision rules.

1¢U

A

2

1¢U

F

2

8.4 THE MANY TYPES OF RISK

Risk may be classified into a number of types. A clear understanding of the different

forms of risk is useful in the evaluation and monitoring of capital projects:

1 Business risk – the variability in operating cash flows or profits before interest. A

firm’s business risk depends, in large measure, on the underlying economic envi-

ronment within which it operates. But variability in operating cash flows can be

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 198

.

Chapter 8 Analysing investment risk 199

Operating gearing example: Hifix and Lofix

Hifix and Lofix are two companies identical in every respect except cost structure. While

Lofix pays its workforce on an output-related basis, Hifix operates a flat-rate wage system.

The sales, costs and profits for the two companies are given under two economic states,

normal and recession, in Table 8.2. While both companies perform equally well under nor-

mal trading conditions, Hifix, with its heavier fixed cost element, is more vulnerable to

economic downturns. This can be measured by calculating the degree of operating gearing:

The degree of operating gearing is far greater for the firm with high fixed costs than for

the firm with low fixed costs. (Chapter 18 further discusses operating gearing.)

Table 8.2 Effects of cost structure on profits (£000)

Hifix Lofix

Normal Recession Normal Recession

Sales 200 120 200 120

Variable costs

60

96

Fixed costs

80

20

Profit/loss 20

20 20 4

Change in sales

40%

40%

Change in profits

200%

80%

2080

160100

For Lofix

80%

40%

2

For Hifix

200%

40%

5

Operating gearing

percentage change in profits

percentage change in sales

heavily affected by the cost structure of the business, and hence its operating gear-

ing. A company’s break-even point is reached when sales revenues match total

costs. These costs consist of fixed costs – that is, costs that do not vary much with

the level of sales – and variable costs. The decision to become more capital-intensive

generally leads to an increase in the proportion of fixed costs in the cost structure.

This increase in operating gearing leads to greater variability in operating earnings.

2 Financial risk – the risk, over and above business risk, that results from the use of

debt capital. Financial gearing is increased by issuing more debt, thereby incurring

more fixed-interest charges and increasing the variability in net earnings. Financial

risk is considered more fully in later chapters.

3 Portfolio or market risk – the variability in shareholders’ returns. Investors can sig-

nificantly reduce their variability in earnings by holding carefully selected invest-

ment portfolios. This is sometimes called ‘relevant’ risk, because only this element

of risk should be considered by a well-diversified shareholder. Chapters 9 and 10

examine such risk in greater depth.

Project risk can be viewed and defined in three different ways: (1) in isolation, (2) in

terms of its impact on the business, and (3) in terms of its impact on shareholders’

investment portfolios. One survey (Pike and Ho, 1991) found that 79 per cent of man-

agers in larger UK firms use project-specific risk and 61 per cent consider the impact

of business risk, but only 26 per cent consider the impact on shareholder portfolios.

In this chapter, we assess project risk in isolation before moving on to estimate its

impact on investors’ portfolios (i.e. market risk) in Chapter 10.

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 199

.

200 Part III Investment risk and return

Table 8.3

Snowglo plc project

data

State of Probability

Cash flow (

£)

economy of outcome A B

Strong 0.2 700 550

Normal 0.5 400 400

Weak 0.3 200 300

Self-assessment activity 8.2

Which type of risk do the following describe:

1 Risks associated with increasing the level of borrowing?

2 The variability in the firm’s operating profits?

3 Variability in the cash flows of a proposed capital investment?

4 Variability in shareholders’ returns?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

8.5 MEASUREMENT OF RISK

A well-known politician (not named to protect the guilty) once proclaimed, ‘Forecasting

is very important – particularly when it involves the future!’ Estimating the probabili-

ties of uncertain forecast outcomes is difficult. But with the little knowledge the man-

ager may have concerning the future, and by applying past experience backed by

historical analysis of a project and its setting, he or she may be able to construct a prob-

ability distribution of a project’s cash outcomes. This can be used to measure the risks

surrounding project cash flows in a variety of ways. If we assume that the range of pos-

sible outcomes from a decision is distributed normally around the expected value, risk-

averse investors can assess project risk using expected value and standard deviation.

We shall consider three statistical measures: the standard deviation, semi-variance and

coefficient of variation for single-period cash flows.

■ Measuring risk for single-period cash flows: Snowglo plc

Table 8.3 shows the information on two projects for Snowglo plc.

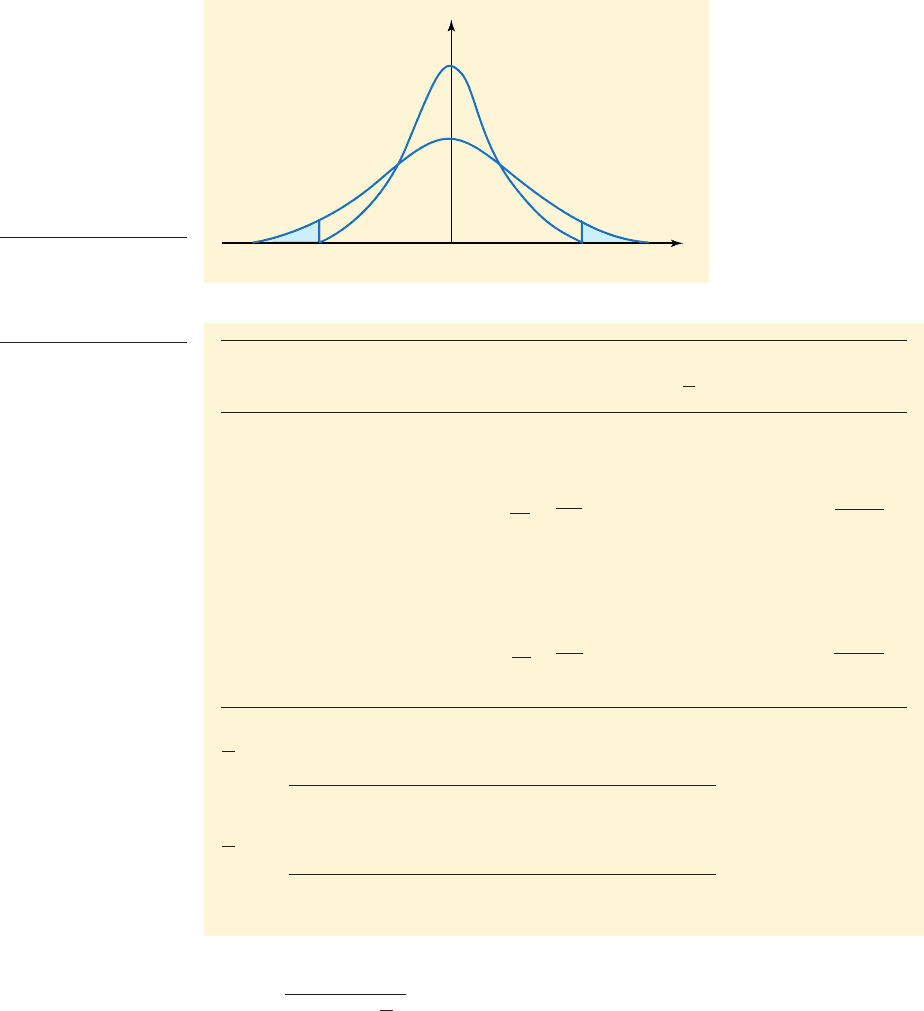

Standard deviation

We have seen that expected value overlooks important information on the dispersion

(risk) of the outcomes. We also know that different people behave differently in risky

situations. Figure 8.3 shows the NPV distributions for projects A and B. Both projects

have the same expected NPV, indicated by M, but project A has greater dispersion. The

risk-averse manager in Snowglo will choose B since he or she wants to minimise risk.

The risk-taker will choose A because the NPV of project A has a chance (W ) of being

higher than X (which project B cannot offer), but also a chance (L) of being lower than Y.

Hereafter we make the reasonable assumption that most people are risk-averse.

The standard deviation is a measure of the dispersion of possible outcomes; the

wider the dispersion, the higher the standard deviation.

The expected value, denoted by is given by the equation:

X

a

N

i 1

p

i

X

i

X,

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 200

.

Chapter 8 Analysing investment risk 201

B

A

W

NPV

XMY

L

Probability

Figure 8.3

Variability of project

returns

Table 8.4

Project risk for

Snowglo plc

Expected Squared

Economic Probability Outcome value Deviation deviation Variance

state (a)(b)

Project A

Strong 0.2 700 140 300 90,000 18,000

Normal 0.5 400 200 0 0 0

Weak 0.3 200 60 40,000 12,000

Variance 30,000

Standard deviation 173.2

Project B

Strong 0.2 550 110 150 22,500 4,500

Normal 0.5 400 200 0 0 0

Weak 0.3 300 90 10,000 3,000

Variance 7,500

Standard deviation 86.6

Alternatively:

86.6

s

B

230.21550 4002

2

0.51400 4002

2

0.31300 4002

2

4

X

A

55010.22 40010.52 30010.32 400

173.2

s

A

230.21700 4002

2

0.51400 4002

2

0.31200 4002

2

4

X

A

70010.22 40010.52 20010.32 400

s

B

s

2

B

X

B

400

100

s

A

s

2

A

X

A

400

200

1f a e21e d

2

21d b X21c a b2

and the standard deviation of the cash flows by:

Table 8.4 provides the workings for projects A and B.

Applying the formulae, we obtain an expected cash flow of £400 for both project

A and project B. If the decision-maker had a neutral risk attitude, he or she would

view the two projects equally favourably. But as the decision-maker is likely to be

risk-averse, it is appropriate to examine the standard deviations of the two proba-

bility distributions. Here we see that project A, with a standard deviation twice that

of project B, is more risky and hence less attractive. This could have been deduced

simply by observing the distribution of outcomes and noting that the same proba-

bilities apply to both projects. But observation cannot always tell us by how much

one project is riskier than another.

s

B

a

N

i 1

p

i

1X

i

X2

2

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 201

.

202 Part III Investment risk and return

Standard deviation Expected value Coefficient of variation

(1) (2) (

)

Project A £173.2 £400 0.43

Project B £86.6 £400 0.22

1 2

Standard deviation Expected value Coefficient of variation

Project F £1,000 £10,000 0.10

Project G £2,000 £40,000 0.05

Self-assessment activity 8.3

Project X has an expected return of £2,000 and a standard deviation of £400. Project Y

has an expected return of £1,000 and a standard deviation of £400. Which project is

more risky?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

Semi-variance

While deviation above the mean may be viewed favourably by managers, it is ‘down-

side risk’ (i.e. deviations below expected outcomes) that is mainly considered in the

decision process. Downside risk is best measured by the semi-variance, a special case

of the variance, given by the formula:

where SV is the semi-variance, j is each outcome value less than the expected value, and

K is the number of outcomes that are less than the expected value.

Applying the semi-variance to the example in Table 8.4, the downside risk relates

exclusively to the ‘weak’ state of the economy:

Once again project B is seen to have a much lower degree of risk. In both cases, the

semi-variance accounts for 40 per cent of the project variance.

Coefficient of variation (CV)

Where projects differ in scale, a more valid comparison is found by applying a relative

risk measure such as the coefficient of variation. The lower the CV, the lower the rela-

tive degree of risk. This is calculated by dividing the standard deviation by the expect-

ed value of net cash flows, as in the expression:

The Snowglo example (Table 8.4) gives the following coefficients:

CV s>X

SV

B

0.31300 4002

2

£3,000

SV

A

0.31200 4002

2

£12,000

SV

a

K

j 1

p

j

1X

j

X2

2

Both projects have the same expected value, but project B has a significantly lower

degree of risk. Next, we consider the situation where the two projects under review are

different in scale:

Although the absolute measure of dispersion (the standard deviation) is greater for

project G, few people in business would regard it as more risky than project F because

of the significant difference in the expected values of the two investments. The coeffi-

cient of variation reveals that G actually offers a lower amount of risk per £1 of expect-

ed value.

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 202

.

Chapter 8 Analysing investment risk 203

Mean–variance rule

Given the expected return and the measure of dispersion (variance or standard devia-

tion), we can formulate the mean–variance rule. This states that one project will be pre-

ferred to another if either of the following holds:

1 Its expected return is higher and the variance is equal to or less than that of the other

project.

2 Its expected return exceeds or is equal to the expected return of the other project and

the variance is lower.

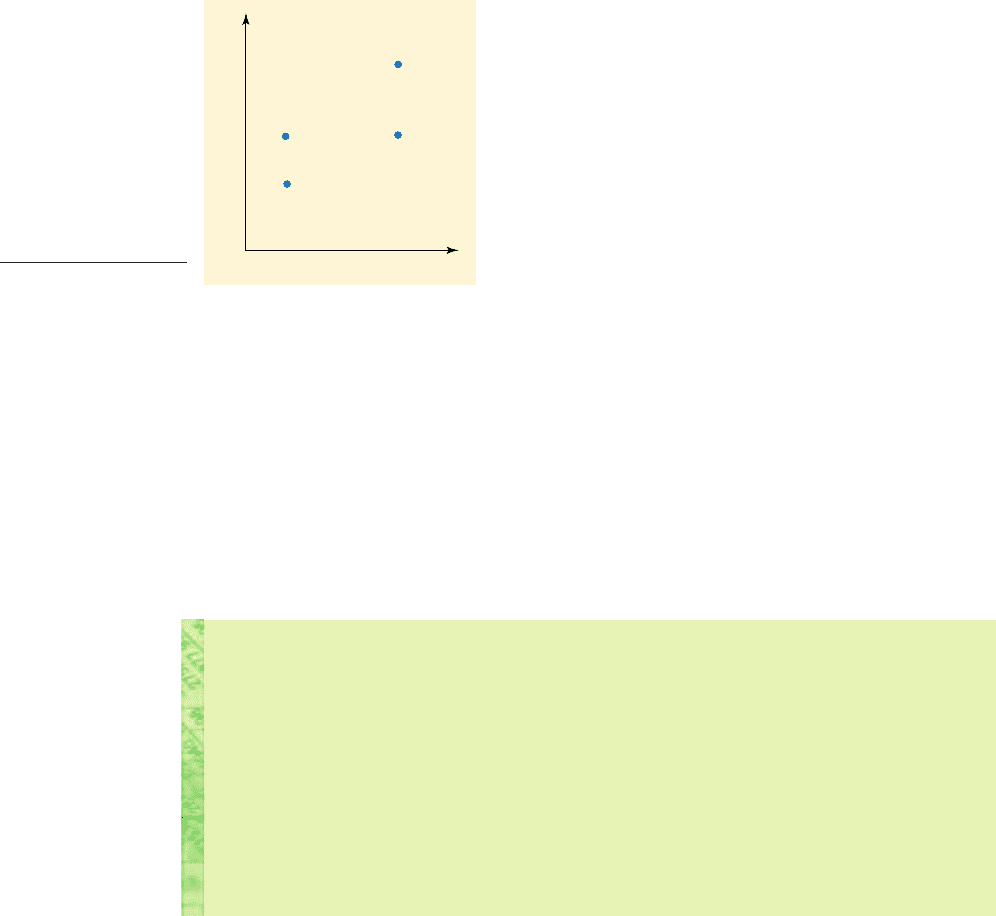

This is illustrated by the mean–variance analysis depicted in Figure 8.4. Projects A

and D are preferable to projects C and B respectively because they offer a higher return

for the same degree of risk. In addition, A is preferable to B because for the same expect-

ed return, it incurs lower risk. These choices are applicable to all risk-averse managers

regardless of their particular utility functions. What this rule cannot do, however, is dis-

tinguish between projects where both expected returns and risk differ (projects A and

D in Figure 8.4). This important issue will be discussed in Chapters 9 and 10.

Self-assessment activity 8.4

What do you understand by the following?

(a) risk

(b) uncertainty

(c) risk-aversion

(d) expected value

(e) standard deviation

(f) semi-variance

(g) mean–variance rule

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

C

A

B

D

Variance

0

Expected value

Figure 8.4

Mean–variance analysis

So far, our analysis of risk has assumed single-period investments. We have conve-

niently ignored the fact that, typically, investments are multi-period. The analysis of

project risk where there are multi-period cash flows is discussed in the appendix to

this chapter.

■ Risk-handling methods

There are two broad approaches to handling risk in the investment decision process.

The first attempts to describe the riskiness of a given project, using various applications

of probability analysis or some simple method. The second aims to incorporate the

investor’s perception of project riskiness within the NPV formula.

We turn first to the various techniques available to help describe investment risk.

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 203

.

204 Part III Investment risk and return

50–5–10–15 10 15 20 25

–25 –20

2,000

3,000

1,000

–1,000

–2,000

4,000

Discount

rate

Capital

cost

NPV

Price

Market size

% Deviation

from expected

value

Figure 8.5

Sensitivity graph

Break-even sensitivity analysis: UMK plc

The accountant of UMK plc has put together the cash flow forecasts for a new product with

a four-year life, involving capital investment of £200,000. It produces a net present value, at

a 10 per cent discount rate, of £40,920. His basic analysis is given in Table 8.5. Which fac-

tors are most critical to the decision?

Investment outlay

This can rise by up to £40,920 (assuming all other estimates remain unchanged) before the

decision advice alters. This is a percentage increase of

£40,920

£200,000

100 20.5%

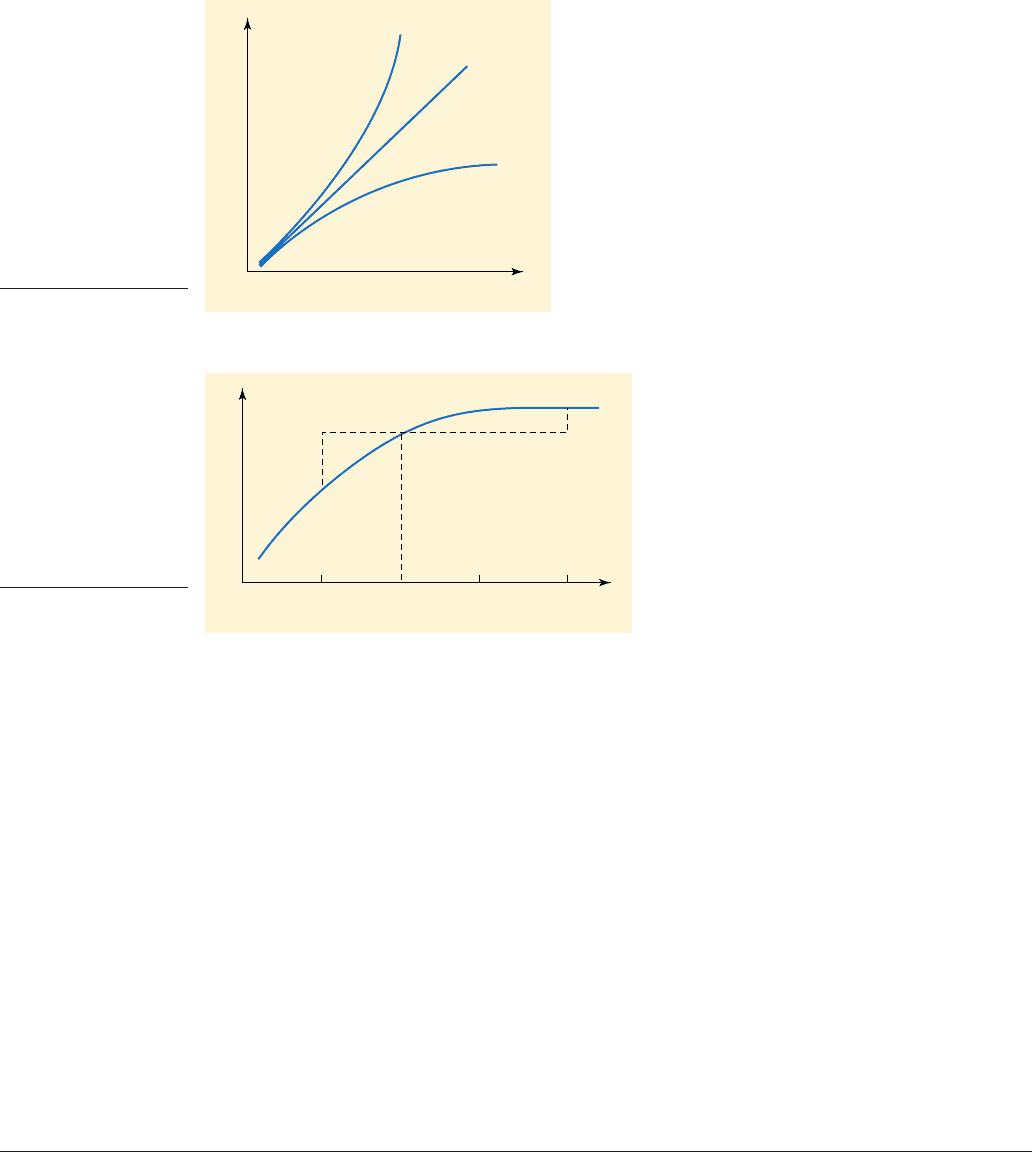

8.6 RISK DESCRIPTION TECHNIQUES

■ Sensitivity analysis

In principle, sensitivity analysis is a very simple technique, used to locate and assess

the potential impact of risk on a project’s value. It aims not to quantify risk, but to iden-

tify the impact on NPV of changes to key assumptions. Sensitivity analysis provides the

decision-maker with answers to a whole range of ‘what if’ questions. For example,

what is the NPV if selling price falls by 10 per cent? What is the IRR if the project’s life

is only three years, not five years as expected? What is the level of sales revenue

required to break even in net present value terms?

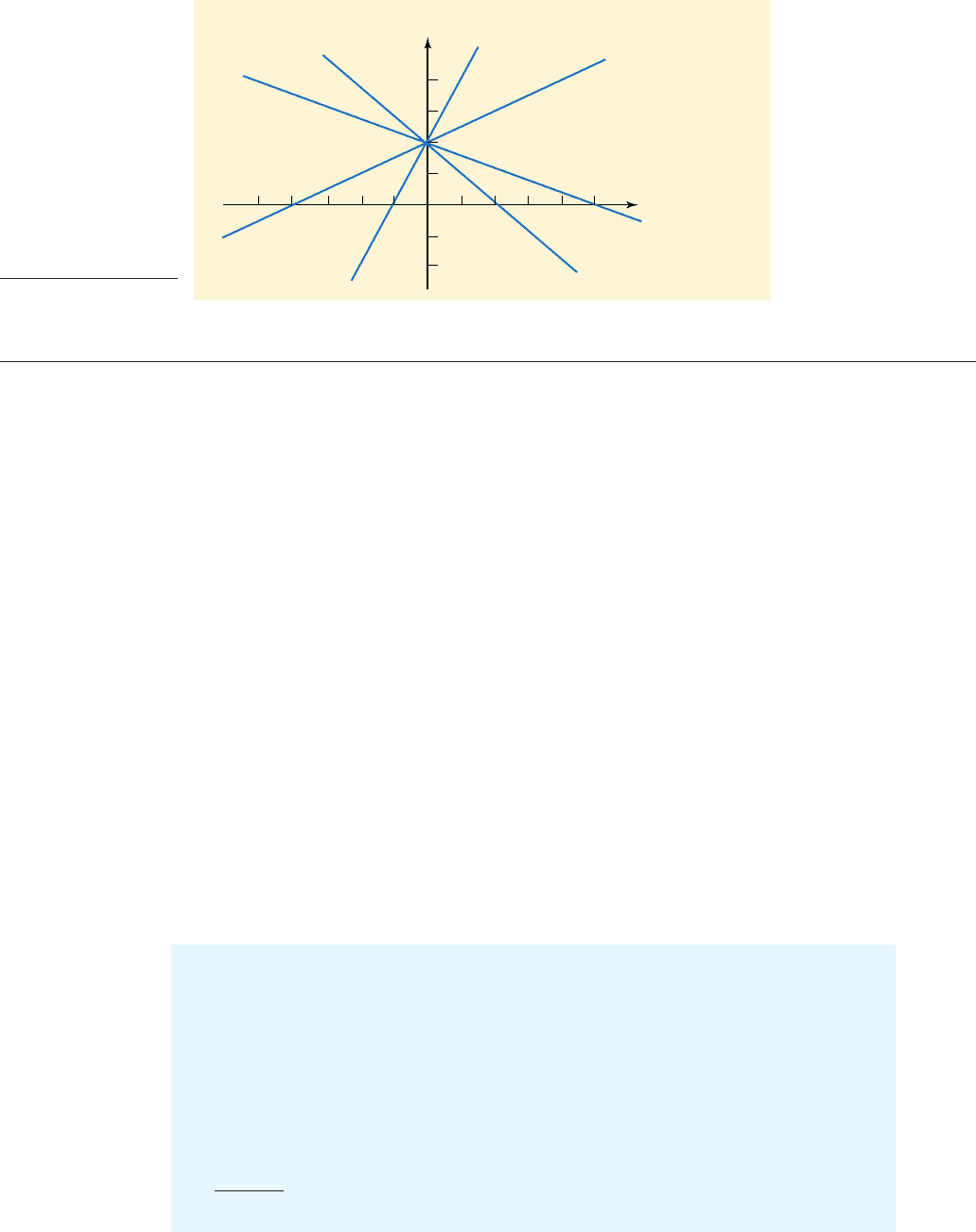

Sensitivity graphs permit the plotting of net present values (or IRRs) against the per-

centage deviation from the expected value of the factor under investigation. The sensi-

tivity graph in Figure 8.5 depicts the potential impact of deviations from the expected

values of a project’s variables on NPV. When everything is unchanged, the NPV is £2,000.

However, NPV becomes zero when market size decreases by 20 per cent or price decreas-

es by 5 per cent. This shows that NPV is very sensitive to price changes. Similarly, a 10

per cent increase in the capital cost will bring the NPV down to zero, while the discount

rate must increase to 25 per cent in order to render the project uneconomic. Therefore, the

project is more sensitive to capital investment changes than to variations in the discount

rate. The sensitivity of NPV to each factor is reflected by the slope of the sensitivity line –

the steeper the line, the greater the impact on NPV of changes in the specified variable.

Sensitivity analysis is widely used because of its simplicity and ability to focus on

particular estimates. It can identify the critical factors that have greatest impact on a

project’s profitability. It does not, however, actually evaluate risk; the decision-maker

must still assess the likelihood of occurrence for these deviations from expected values.

CFAI_C08.QXD 10/28/05 3:59 PM Page 204