Pavlac B.A. A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities throughout History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

66

CHAPTER 4

started because three goddesses fought over who was the most beautiful. Despite,

or perhaps because of, this divinely trashy behavior, the Greek myths conveyed a

rich and deeply textured heritage. How the human spirit rose above fate and the

cruelty of the gods, not the gods themselves, inspires us even today.

The Greeks revered their gods and ancestors by forming restrictive cults that kept

outsiders out of each polis. Indeed, each city was dedicated to a deity, who might

also have been believed to be a parent of semidivine heroic founders. Civic cults

structured the worship of the city’s gods in particular and all gods (out of concern to

neglect no divine power). The polis organized religious ceremonies as a political

responsibility. As mentioned before, the Greeks had no priestly caste or class.

Instead, every citizen accepted an obligation to ensure that the civic rites of appeas-

ing and worshipping the gods were performed properly. Consulting the gods

through oracles provided guidance for everyday activities and major political deci-

sions. The city fathers brought the cultic practices into their own homes by tending

sacred fires (of which the Olympic torch is an offshoot) and sharing sacred meals.

Some Classical Greeks soon turned away from the austere formality of civic cults

and the lack of spirituality in the Greek pantheon. They instead embraced mystery

cults, which were centered on rituals of fertility, death, and resurrection. We know

little about the worship that focused on deities such as Demeter or Dionysius, since

their followers kept most of their activities secret. The cults seemed to promise a

conquest of death. Although the cults were popular privately, every citizen still

upheld the civic rituals in public. All governing was performed in a religious context.

Little in these religious cults, however, offered much of a guide for the moral

or ethical decisions that always have been at the heart of politics. For answers, the

Greeks took one important step beyond religion with their invention of philosophy.

The word philosophy is from the Greek for ‘‘love of wisdom.’’ Philosophy began in

the sixth century

B.C.

in Ionia, where some men began to wonder about the nature

of the universe. Compared with modern scientific investigation (explained in chap-

ter 11), the Greek theories about how the universe was based on air or water seem

rather silly. But they were progress. Instead of relying on myth for explanation,

these philosophers began to apply the human mind. The concept that the human

mind can comprehend the natural world, rationalism, became a key component

of Western civilization.

The philosophers who examined geometry or the composition of matter were

soon joined by others who speculated about humans. By the fifth century, the so-

called Sophists (‘‘wise men’’) had started to create ideas about moral behavior that

are still with us today. They were itinerant teachers who, for a fee, educated Greeks

about the ways of the world. Several distinct schools of thought competed for atten-

tion. Skepticism doubted knowing anything for certain. Hedonism pursued plea-

sure as the highest good. Cynicism abandoned all moral restraints to gain power

over other people. Many Sophists seemed to offer methods for becoming wealthy

without worrying about moral scruples. Against them, a trinity of Greek philoso-

phers offered alternative views for human action.

First, Socrates (b. 469–d. 399

B.C.

) argued against the materialism of the Soph-

ists. As he strolled through the streets and plazas of Athens, Socrates constantly

PAGE 66.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:27:47 PS

TRIAL OF THE HELLENES

67

asked questions of his fellow citizens. Moreover, through questioning, he tried to

give those who would engage in his conversation the chance to learn. This is the

Socratic method. Socrates claimed to hold no set of doctrines he wanted to teach;

he only desired to seek the truth. Indeed, he said that he knew little at all. When

the Delphic Oracle had answered someone’s query as to who was the wisest man

in Greece with the answer ‘‘Socrates,’’ the philosopher was at first puzzled. Then

he realized that his self-description (‘‘the only thing I know is that I know nothing’’)

explained the oracle. He concluded that true wisdom was self-knowledge. There-

fore, Socrates advocated that every person should, according to the Delphic Ora-

cle’s motto, ‘‘know thyself.’’

Amid the conflict of the Peloponnesian Wars, the trial of the philosopher Socra-

tes highlights the Greeks’ failure to live up to high ideals. In 399

B.C.

, as the Atheni-

ans tried to recover from their defeat by Sparta, a new democratic leadership

charged the oligarchic Socrates with two crimes: blasphemy and corruption of the

young. For one day, a jury of five hundred citizens who had been chosen by lot

heard the arguments, where plaintiffs and defendants represented themselves. Soc-

rates defended himself of the first charge by openly mocking the nonsense of Greek

mythology. How could someone believe in gods who did so many silly and cruel

things to humans? He defended himself against the second charge by saying he only

encouraged young people to become critical of their elders and society. Socrates

gladly saw himself as an annoyance, a gadfly, provoking and reproaching the leaders

of Athens. The jury found him guilty. Consequently, when he wryly suggested his

own punishment be a state pension, they sentenced him to death. Obedient to the

laws of his city, Socrates committed suicide by drinking hemlock, a slow-acting

paralytic poison. This political trial illuminated how democracy failed to adapt to

changing circumstances.

Second, Socrates’ pupil Plato (b. 427–d. 347

B.C.

) explored new philosophical

directions. Since Plato wrote his philosophy in the form of dialogues conducted by

his master Socrates, it is sometimes difficult to define where Socrates’ views end and

Plato’s begin. Still, Plato offered the doctrine of ideas, or idealism, as an answer for

the nature of truth. In his famous allegory of the cave, Plato suggested that our

reality is like people chained in a cave who can see only strange shadows and hear

only odd noises. But if a person were to break free and climb out of the cave,

though blinded by sunlight, he would confront the genuine reality. Actual forms in

our world only poorly imitate real universal ideas. How could the person who

sees truth then describe it to those still inside the cave, who do not share such an

experience? Plato saw the philosopher’s task as describing ultimate reality.

Third, Plato’s student Aristotle (b. 384–d. 322

B.C.

) turned away from the more

abstract metaphysics of his teacher to refocus on the natural world and people’s

place in it. Thus, he studied nature and wrote books on matters from zoology to

meteorology that would define scientific views for centuries (even if many were

ill informed by our modern standards). Aristotle’s rules of logic covered politics,

literature, and ethics. He used syllogisms, called dialectic logic, where two pieces

of known information are compared in order to reach a new knowledge. It was the

most powerful intellectual tool of its day, and indeed long after. Finally, Aristotle

promoted the ‘‘golden mean’’ of living a life of moderation.

PAGE 67.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:27:48 PS

68

CHAPTER 4

Altogether, these philosophers helped to establish an idea called humanism.

As this book will use it, humanism means that the world is to be understood by and

for humans. A phrase by the philosopher Protagoras, that ‘‘man is the measure of

things,’’ embodies the approach. (And the Greeks usually meant specifically ‘‘man,’’

considering females to be an inferior form of the idealized male.) According to

humanism, our experiences, perceptions, and practices are important and useful

in dealing with life, here and now. This belief has repeatedly offered an alternative

to religious ideas emphasizing life after death.

One of the great humanistic triumphs of Greek culture was its literature. Many

educated people knew the epic poems of The Iliad and The Odyssey by heart. Lyric

poetry also was quite popular. Then, as today, lyric poetry meant shorter, personal

poetry about feelings, rather than stories. In Greece, all poetry was literally said, or

sung, while someone played the lyre, a stringed instrument, or a flute. Many Greeks

declared Sappho to be one of the greatest lyric poets. Instead, more people now

know her name as standing for female same-sex love, sapphism; the alternate term

lesbianism also is connected to Sappho, namely from the island where she had

her school, Lesbos. As far as literary historians can tell, though, she loved both men

and women. Her poetry has come down to us in only a few fragments (much of it

destroyed later by Christians offended by her sensuality).

When the Greeks combined literature and performance, they invented theater

(see figure 4.2). Like politics, theater had a religious context in Greek culture. Ritual

stories of the gods turned into festivals, where actors dramatized the poetry with

voice, movement, music, and even special effects. The most famous of the last is

the deus ex machina (Latin for ‘‘god from the machine’’), where a tangled plot

could be instantly resolved by divine intervention, an actor playing a god lowered

onto the stage from above. The most popular and important plays were tragedies,

where the protagonist of the story fails, often due to pride (in Greek, hybris). The

most famous tragedy is Oedipus Tyrannos (‘‘Clubfoot the Tyrant,’’ usually called

Oedipus Rex). By trying to do what is right, the title character causes suffering.

During the day on which the play takes place, Oedipus reviews his past. He has left

his home of Corinth because he heard a prophecy that he would be responsible for

the death of his parents. After killing the monstrous sphinx by answering her ques-

tion, Oedipus has taken over nearby Thebes, whose ruler was recently killed by

bandits. Oedipus discovers in the course of the play that he was actually adopted,

had killed his own father, and had married his mother. She hangs herself, and he

blinds himself and goes into exile.

Performances of several tragedies would be balanced by a comedy. Some Greek

Figure 4.2. The theater outside the Greek city of Miletus in Ionia lies poised for the next

performance more than a thousand years after its last.

PAGE 68.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:28:01 PS

TRIAL OF THE HELLENES

69

comedies were merely bawdy farces, but others rose to transcendent political satire.

For example, Lysistrata by Aristophanes, first performed during the Peloponnesian

Wars, managed to harpoon both male aggression and ego. The heroine of the title

successfully organizes the women of two warring poleis to go on a sexual strike

until their men stop fighting.

It often happens that enduring culture is produced during brutal war. As rival

Greek kings too often fought over their shares of Alexander’s empire, the ruling

Greek elites fostered a new phase of creativity called Hellenistic civilization (338–146

B.C.

). While critics often characterize Hellenistic culture as less glorious than Athens’

Golden Age, elites spread that age’s classic works along with fostering their own new

products. The cities became cosmopolitan, growing vibrant with peoples from many

diverse ethnic groups. Alexander founded several and named them after himself,

such as the most successful Hellenistic city, Alexandria, located at the mouth of the

Nile. Streets laid out on grids connected places of education and entertainment:

schools, theaters, stadiums, and libraries. Commerce in the Eurasian-African trade

networks supported luxuries. Sculpture conveyed more emotion and character than

the cool calm of the Classical Age. Greek philosophers who studied nature gained

enduring knowledge in astronomy, mechanics, and medicine.

The two most popular philosophies to come out of the Hellenistic period

reflected pessimism about the future, however. Epicureanism sought to find the

best way of life to avoid pain in a cruel world. Epicureans taught that the good life

lay in withdrawal into a pleasant garden to discuss the meaning of life with friends.

In contrast, stoicism called for action. Stoics accepted the world’s cruelty but called

on everyone to dutifully reduce conflict and promote the brotherhood of mankind

(women not included, as usual). This duty should be pursued even if one failed,

which was likely.

The Greeks ultimately failed largely because of fighting among themselves, not

because of external enemies. A few of their city-states managed to defeat the world’s

greatest empire. They briefly held supreme power over masses of Asians and North

Africans. The Greeks, however, were too few and too divided to permanently domi-

nate these peoples. Although they contributed many high ideals, they betrayed

them just as often. The Greek heritage of art, literature, and philosophy enriched

the peoples of the ancient world, as it continues to do for many in the world today.

Nevertheless, democracy fell to imperialism; imperial unity fell to particularism;

and the intellectual honesty of Socrates fell to fear. The Greeks’ cultural arrogance

condemned them to become marginalized instead of being the ongoing bearers of

history. The next founders of Western civilization would soon conquer most of

what Alexander had and add yet more to the foundations of the West.

Review: What Greek culture expanded through the ancient West?

Response:

PAGE 69.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:28:02 PS

PAGE 70.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:28:02 PS

5

CHAPTER

Imperium Romanum

The Romans, 753

B.C

.

to

A.D.

300

W

hile Greeks quarreled themselves into fragmentation, another people, the

Romans, were proving much more adept at power politics. The Romans

forged the most important and enduring empire of the ancient world.

This achievement is all the more impressive since Rome started out as just another

small city-state. Roman success can, perhaps, be attributed to their tendency to be

even more vicious and cruel than the Greeks, although, as seen in the preceding

chapter, the Hellenes could be fairly nasty themselves. The Romans’ empire rose

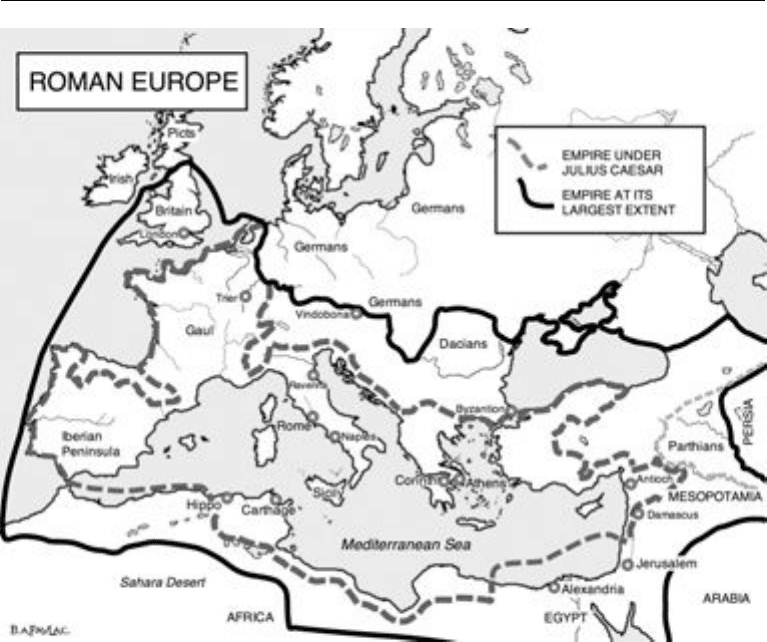

through military supremacy, cultural diversity, and political innovation (see map

5.1). The glory of the Imperium Romanum, the Roman Empire, still appeals to the

historical imagination.

WORLD CONQUEST IN SELF-DEFENSE

The city-state of Rome was, at first, small and surrounded by enemies. According

to Rome’s own mythological history, refugees from the destroyed city of Troy in

PAGE 71.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:26:59 PS

72

CHAPTER 5

Map 5.1. Roman Europe

Asia Minor had fled westward, eventually settling in the province of Latium, which

was halfway down the western coast of the Italian Peninsula. It was there, according

to the story, that a she-wolf raised two twin brothers, Romulus and Remus. As

adults, they argued about the founding of a new city. In one version, in the year

753

B.C.

Romulus killed his brother Remus and named the new city after himself.

Thus Rome was founded on fratricide. The Romans were proud of their violent

inheritance; they themselves later became some of the best practitioners of state-

sponsored violence in the history of the world.

Whatever truth may lie in the myth of Romulus, Rome’s actual founders took

advantage of a good location. The Tiber River provided easy navigation to the sea,

yet the city was far enough inland to avoid regular raids by pirates. The city also lay

along north-south land routes through central Italy. Hence, the founders had ready

contact with nearby stronger societies and began to borrow from them liberally.

The early Romans cobbled together a hodgepodge culture, learning much from the

Greeks who lived in the cities of Magna Græcia in southern Italy and Sicily. The

Romans borrowed the Greek Olympian gods and goddesses, usually giving the dei-

ties new names better suited to the Romans’ language of Latin. Another important

influence on Roman culture was the neighbors to the north, the Etruscans (who

have lent their name to Tuscany). Actually, for much of Rome’s early history, the

city itself was so weak that Etruscan kings ruled the Romans.

PAGE 72.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:27:29 PS

IMPERIUM ROMANUM

73

Roman myth supplied another violent story about winning freedom from the

Etruscans. According to the legendary history, Sextus, the son of an Etruscan king,

lusted after Lucretia, the wife of a Roman aristocrat. When the husband was away

from home one day, Sextus demanded that Lucretia have sex with him. If she did

not, he promised to kill both her and a male servant. He promised he would then

put them in bed together and report that he had found and rightfully killed them

for shameful adultery and violation of class distinctions. So Lucretia gave in to Sex-

tus. When her husband and his companions returned home, Lucretia confessed

what had happened before stabbing herself in the heart to remove her shame. The

outraged Romans organized a rebellion and threw the Etruscans out of their city.

Thus, rape and suicide inspired Roman political freedom.

This charming tale passed down through the generations probably has as little

fact behind it as the tale of Romulus and Remus. For the Romans, though, this myth

proudly showed once again how violence and honor were woven into their history.

Moreover, historical and archaeological evidence indicates that around 500

B.C.

the

Romans had indeed won freedom from Etruscan domination.

What the Romans then did with their new freedom was something remarkable:

they chose a democratic form of government. Technically, the Romans founded a

republic, where citizens chose other citizens to represent them. So, like the

Greeks, they had no kings, although unlike the Greeks, they did not require all

citizens to hold public office. The most important government institution was the

Senate, a council of elders who protected the unwritten constitution and were

involved in all major decisions. Initially, the Senate had three hundred members

who served for life and were supposed to embody the collective wisdom of the

state. As the head of their city-state, the Romans also elected two consuls as adminis-

trators. These two ran the city government, commanded the army, spent the money,

and exercised judicial power. The two consuls held office at the same time, and

each had veto power over the other. The consuls served only a year, and only two

terms were permitted for any individual in a lifetime. Many other magistrate posi-

tions (praetors, questors, censors, lictors) were similarly limited. Thus, the Senate

and People of Rome (using the initials SPQR) began an elaborate system of checks

and balances, where, according to their constitutional structure, no single individ-

ual or family could gain too much power.

Officially, all male citizens voted and held official government positions, while

privately, a handful of families actually made the major decisions behind the scenes.

Roman society was divided into two main groups: the aristocrats (a few dozen fami-

lies called patricians) and the free-born peasants (called plebians). In the early

centuries of the Roman Republic, patricians controlled all the political positions.

Indeed, someone could hardly hold office without patrician wealth since govern-

ment service was unpaid. After the Romans reformed their military along lines simi-

lar to the Greek phalanx, however, male peasants replaced aristocrats as the

essential warriors of Rome. Inevitably, as patricians declined in number and, more

especially, in significance on the battlefield, the plebians wanted a larger say in

government. Their demands followed the Greek example of political change follow-

ing military innovation.

A key event that pushed these military changes was Rome’s near destruction by

PAGE 73.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:27:30 PS

74

CHAPTER 5

the Celts or Gauls. These peoples spread through primitive Europe from the sixth

through the fourth centuries

B.C.

Many eventually settled in what is now France and

the British Isles, retaining their ethnic identity to the present. In the course of their

ancient travels, they stormed down the Italian Peninsula, plundering and laying

waste. They attacked Rome itself in 390

B.C.

, occupying and destroying much of the

city. Only the last fortress on the Capitoline hill managed to hold out, barely saved

from a surprise attack by the honking of disturbed geese. The Romans then

regrouped and drove off the Celts. This Celtic invasion wounded the Roman world-

view. The Romans decided to make their nation so powerful that it would never be

conquered again, however briefly. For eight hundred years they succeeded in this

goal—a good run for any empire.

The key military innovation that enabled such success was the Roman legion.

The Romans improved upon the Greek phalanx, which they must have encountered

in Magna Græcia. The legion used smaller, more maneuverable groups of men who

marched in formation but threw their spears at the enemy. Then, in the clash of

close combat, the legionaries stabbed their foes with their short swords. Supported

by cavalry and siege weapons, the Romans replaced the Greeks as the best warriors

of antiquity.

So, while the city-state used aggression against its neighbors, its own citizens

sought more representative government where disagreements could be worked out

peacefully. The military participation by the plebians as troops for the burgeoning

empire unlocked their access to power. The peasants threatened to strike rather

than fight. The aristocratic patricians, numerically incapable of defending Rome on

their own, began to make concession after concession. Patricians created the politi-

cal office of the tribunes, who protected the plebian citizens from aristocratic mag-

istrates who unjustly intimidated plebians. Tribunician authority was one of the

broadest and most powerful in the state. Patricians also soon allowed the plebians

a major political body of their own: the Assembly of Tribes. By 287

B.C.

, the Assembly

gained the power to make binding laws, declare war and peace, and elect judges.

Patricians finally allowed wealthy plebians to become magistrates as well. Thus,

more checks and balances perfected the ideal republican government of the Senate

and People of Rome (SPQR).

Although the Romans developed republican government at home, they had to

decide how to treat their new subject peoples in what had become an empire. By

250

B.C.

, the Roman legions took over most of Italy, including ‘‘foreigners’’ such

as the Samnians, who were actually more native to the peninsula than the Romans

were. The secret to Roman success was not pure military force but a good dose of

inclusiveness, which had been so foreign to the Greeks. The Romans offered a

romanization policy to many of the survivors in their new conquests. The van-

quished were allowed to become more like Romans instead of beaten people.

Locals had the option of keeping local govern men t and even their traditional gods

and religion. All they had to do was accept Roman control of foreign affairs, con-

tribute taxes, and provide military service. While originally only Roman citizens

held the political power of voting and holding important offices, their subject

peoples soon gained these privileges as well, especially as they intermarried with

Roman families. Slowly, naturally, Roman culture took over as other peoples

throughout the Italian Peninsula were romanized. Many peoples gave up their

PAGE 74.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:27:30 PS

IMPERIUM ROMANUM

75

own languages and adopted Latin, accepted the sensible Roman laws, worshipped

the Roman deities, and even espoused Roman virtues like responsibility and seri-

ousness.

The city-state of Rome became the model throughout its empire (in fact, if not

yet in name). The center of Roman society was the city, even though most people

lived and worked in the countryside as farmers. Where cities existed, the Romans

transformed them; where cities did not exist, the Romans built them. Most of these

cities were small, with only a few thousand inhabitants each. The heart of each city

was the forum, a market surrounded by government buildings and temples. The

public bathhouse was the most essential institution of civilized life—the Romans

were clean people. For other entertainment they built theaters for plays, amphithe-

aters for the brutal slaughter of beasts and gladiators, and, most popular of all,

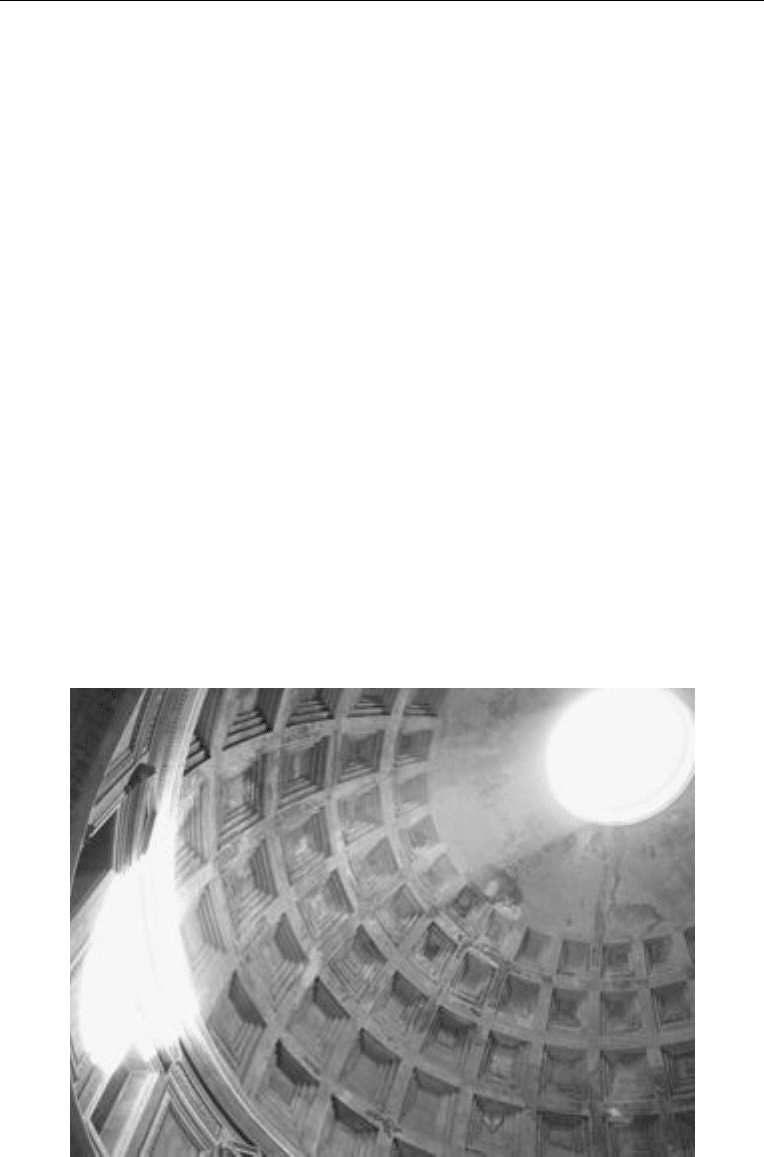

stadiums for the chariot races. Architectural innovations such as the arch and the

dome, as well as the use of concrete as a construction material, allowed Roman

cities to be built taller, more graceful, and more grand than any other cities in the

ancient world. The dome of the Pantheon has inspired architects ever since (figure

5.1). Aqueducts brought in fresh water from distant hills and springs (figure 5.2).

The Roman roads were so well designed that some, such as the Appian Way from

Rome to Naples, are still being driven on today. While the roads were meant to

serve the military first, commerce and civil communication naturally followed and

flourished. Roman roads were so well built and widespread that ‘‘all roads lead to

Rome’’ became a byword for their civilization.

As the Romans marched along these roads, they bore their laws to other peo-

ples. Roman law not only supported one of the most sophisticated governments of

Figure 5.1. Light shining through the oculus of the dome of the

Pantheon in Rome.

PAGE 75.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:27:57 PS