Pavlac B.A. A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities throughout History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

76

CHAPTER 5

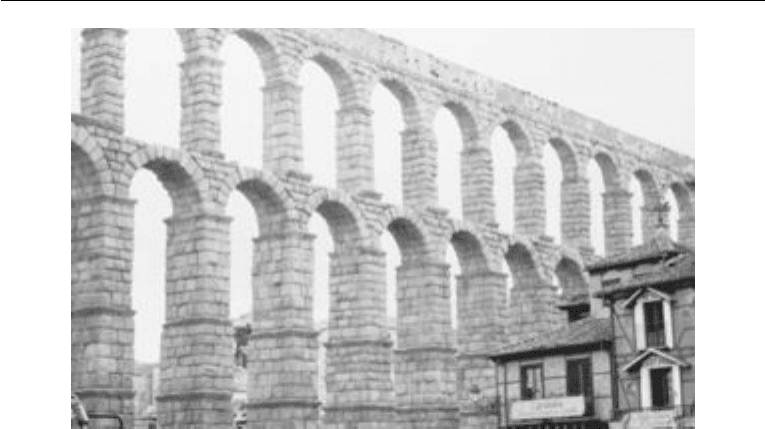

Figure 5.2. Roman civilization relied on clean, fresh water, here brought

into Segovia in Spain by a tall aqueduct.

the ancient world but also influenced other legal systems for centuries to come. The

founding point was around 450

B.C.

, when the plebians insisted on a codification of

laws, the Twelve Tables. Roman magistrates defined law for everyone’s benefit. Clar-

ity about the laws protected citizens against abusive government. Both the patrician

and the plebian could appeal arbitrary enforcement of rules by a magistrate.

Roman law became a flexible system that recognized political change. Divine

law, such as what Hammurabi or Moses received, could not be changed except by

the gods. But the Romans began to invent the idea of natural law. This theory

accepted that deities designed nature and humans to act in a certain way, but it

proposed that human understanding of nature could change as we learn more.

Through practice and experience, humans could create laws that were in better

harmony with the natural order, consequently shaping a more just society. The

Romans thought that if a law did not work, then a new one should be fashioned.

Legal decisions and judgments were supposed to be founded on facts and rational

argumentation, not divine intervention. As such, Roman law became the basis for

many European legal systems today.

The Romans also established that all citizens should be treated equally by the

law (with the usual exemption of women, of course). Expanding rights of citizen-

ship broke down the barriers between upper and lower classes, ethnic Romans and

others. Citizenship granted important status and political participation (although,

of course, while women might be citizens and had some rights over property, the

political system shut them out). To manage this growing and complicated system,

the Romans also invented professional helpers in the law: lawyers. Roman lawyers

had as bad a reputation in their own time as many lawyers have today. They were

seen as greedy, loud, and annoying. Regardless, lawyers were essential to the

smooth functioning of civil society. The Roman legal and political systems allowed

people to have more of a voice and choice in politics than in most other societies

PAGE 76.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:28:36 PS

IMPERIUM ROMANUM

77

in the ancient world. A republican government designed for a city-state, however,

found itself strained as it expanded ever further. The romanization policy could not

resolve increasing tensions within Rome’s imperial rule.

Review: How did Rome grow from a small city-state to a vast multicultural empire?

Response:

THE PRICE OF POWER

Despite the admirabl e legal innovatio n, civil socie ty in Rome nearly collapsed in the

third century

B.C.

because of the Roman addiction to world domination. Their military

success fed the Romans’ appetite for conquest. The next hill always hid some possible

danger to Rome, and such a threat forever justified another expediti on. Soon the

Romans deci ded not to stop at th e water’ s edge of the Italia n Pe nins ula a nd se t their

eyes on Sicily. This target, howev er, led to a life-or-death c risi s for Rome.

As seen in Chapter 4, the Phoenicians had been Middle Eastern competitors

with the Greeks in forming colonies across the Mediterranean. Their major city had

become Carthage, located on the north coast of Africa across the sea from Sicily.

Phoenician and Greek colonies in Sicily controlled the central Mediterranean, as

the Athenians had recognized during the Peloponnesian Wars. Greek cities com-

plaining of Phoenician oppression gave the Romans the opportunity to intervene

in the name of defending liberty. The Phoenicians could not allow the Romans

expansion onto the island. The Romans were determined. So, from 264 to 146

B.C.

,

several generations of Romans fought the Punic Wars (named after the Latin word

for the Phoenicians).

The most memorable stage of the Punic Wars was the invasion of Italy by the

Carthaginian General Hannibal. In 218

B.C.

, he marched his armies (including war

elephants) from Carthaginian territories in the Iberian Peninsula over the Pyrenees

and Alps to enter Italy from the north. This brilliant feat of military command and

logistics astonished the Romans. Unfortunately for Carthage, Hannibal failed to

seize his most important objective, Rome itself. He did rampage up and down the

peninsula, causing great fear and considerable damage, but was unable to inflict a

fatal defeat on Rome. This delay in capturing Rome gave the Romans the chance to

learn from Hannibal’s strategy and tactics. They counterattacked by invading Africa

in 203. Hannibal returned to defend his own capital city of Carthage. The next year

PAGE 77.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:28:37 PS

78

CHAPTER 5

they fought at Zama. The Romans defeated the fearsome Phoenician elephants by

frightening them with trumpets or letting them pass through the lines without

opposition. The legions surrounded the rest of the Carthaginian army and forced

Hannibal to surrender.

The Pho enic ians, sev erel y weakened by this defeat, o ffer ed n o further threat

to Roman exp ansi on. W ithi n only a few years, though, d emagogu es in Rome

began to cha nt th e slogan ‘ ‘Carthago delenda est’’ (‘‘Car tha ge must be

destroyed’ ’). T he Ro mans finall y ca rrie d out that final devastat ion i n 146

B.C.

,

tearing dow n the city and sowing the fields with salt so t hat n oth ing would grow

again. The cultu ral liberties Romans had al lowe d to other defeated societies were

not per mitted here. Potential Phoenic ian contribut ions to R oman civiliza tion

were re ject ed, its litera ture and cultu re erased. Rome wielded undisp uted mas-

tery over the Western Mediterr ane an.

In the same year, coincidental ly, the R oman s gained a stra teg ic footho ld in

the Eastern Mediterr anea n. Since the collapse of Alexand er’ s empire, the Greeks

had been fighting among one another. The Macedonia n kingdom had continu-

ously tried to dominat e the Greeks in the southern tip of the Balkan Peninsul a,

but supremacy remained elusiv e. Some Greeks, seekin g help against the Macedo-

nians, began to i nvite the Romans in as media tors , then as prot ecto rs. Soon the

Romans stayed as rule rs. Many Greeks accepted the Romans, who brought o rder

and peace. Those Greeks who resisted were c onque red and enslaved. In 146

B.C.

,

the destruction of Corint h, the la st independen t Greek ci ty- state in the Balkan s,

marked the e nd of resi stan ce to Roman rule. The Romans were well on their way

to declaring the Medi terr anea n Mare Nostrum (‘‘Our Sea’’).

The Romans did not notice at first that their victories came at great cost, as

expanding an empire so often does. The weak spots in Rome’s society grew worse.

One great flaw was the classic economic recipe for social disaster: the cliche

´

of ‘‘the

rich get richer while the poor get poorer.’’ The vast and productive new provinces

fell under the exploitation of the aristocrats of Rome. As these patricians plundered

the distant lands, discontent spread abroad while envy arose at home. One of the

great new sources of wealth was the enslavement of the defeated peoples, who

were forced to work on large plantations (called latifundia). The plantation owners

began to grow cash crops such as olives and wine, which outsold the produce of

simple farmers. Before the Punic Wars, the farmer-plebians had been the backbone

of Roman society and the army. Afterward, economic competition led rich slave

owners who were profiting from slave labor to grow richer while free peasants

lost their farms. These unemployed masses, forming the new social class of the

proletariat, migrated to the cities, especially to Rome itself.

This mass urban migration shredded the social fabric of urban life. To keep the

poor occupied, the patricians created an expensive welfare system known as ‘‘bread

and circuses.’’ They handed out grain (the bread) and provided entertainments (the

circuses—meaning chariot races on which people gambled). Many other Romans

increasingly complained that traditional values were vanishing. Effeminate Greek

ways were becoming more fashionable, especially the Greek custom of older men

closely bonding with adolescent boys. Meanwhile the Roman wealthy noble eques-

trian class (named after its members’ ability to afford horses for cavalry service)

PAGE 78.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:28:38 PS

IMPERIUM ROMANUM

79

resented the aristocratic patricians. Despite having become wealthy from the bur-

geoning trans-Mediterranean trade, their modest family connections and nonpatri-

cian status excluded equestrians from the true mechanisms of power.

By the late second century

B.C.

, these social tensions sparked civil wars that

lasted for the next hundred years. In such times of emergency, Roman constitu-

tional law provided for tough solutions. For example, the Senate might appoint a

sole dictator, who did not have to worry about another consul second-guessing his

decisions during a six-month term. Or the Romans practiced proscription to

remove overly powerful politicians. When a politician’s name was posted on the

rostrum, the speaking platform of the tribunes, he was declared an outlaw. Anyone

could kill him without penalty—a fate rather more harsh than the Athenian ostra-

cism and exile. Meanwhile, the patricians divided into two factions. Those called

optimates united to preserve oligarchy with as few social or economic reforms as

possible. Those called populares advocated democracy, a broader political base,

and land reform.

Two patrician brothers in the populares party, Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus,

tried to help the plebians, as the tyrants had once done in Greece for the common-

ers. In doing so, the Gracchi brothers used extralegal violence to their advantage.

In turn, the rival optimates led mobs to kill them both in 133

B.C.

Their deaths

meant that the previous system of democratic politics, where checks and balances

peacefully compensated for class differences, fell to fights over tyranny.

Violence soon became the routine means to solve political problems. A new

permanent standing army only fueled bloodshed. Rome had risen to regional

supremacy based on the idea of citizen-soldiers, peasants who would serve for set

terms in an emergency. Late in the second century, imperial defense and the danger

of slave revolts required an army of recruits who served their whole working lives.

Many recruits came from newly conquered peoples who had not been fully con-

verted to republican-style politics. This professionalization led to soldiers becoming

more loyal to their commanders than to the idea of Rome. Soon, generals such as

Marius and Sulla began to fight one another over the wealth and power of the

empire, while soldiers and citizens paid with their lives. Dictators stayed in power

for the long term instead of only during a crisis. Proscription became a regular

practice to eliminate hundreds of enemies rather than a rare tool to maintain a

constitutional balance. The ability to intimidate and kill mattered more than the

talent to persuade. The Roman Republic staggered from bloody crisis to crisis.

Review: How did Rome’s conquests end in a long civil war?

Response:

PAGE 79.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:28:38 PS

80

CHAPTER 5

THE ABSOLUTIST SOLUTION

Only the collapse of the democratic-republican government and the establishment

of absolutism resolved Rome’s political and social crises. One politician and gen-

eral, Julius Caesar (b. 100–d. 44

B.C.

), almost succeeded in restoring order. Caesar

rose to prominence and popularity as a leader of the populares.In62

B.C.

he formed

the First Triumvirate, a three-man coalition with two other powerful Romans, Pom-

pey and Crassus. They briefly restored peace to the political system.

Caesar’s ambition was to surpass his two partners, who had gained reputations

as generals. Pompey already had a solid reputation as a commander, having con-

quered Hellenistic kingdoms in Asia Minor and the province of Judaea, thus bring-

ing the homeland of the Jews into the growing Roman Empire. Crassus had crushed

the revolt led by Spartacus, a free man who had fought in Rome’s army only to be

enslaved to fight as a gladiator. In 73–71

B.C.

, Spartacus and his army of rebel gladia-

tors and other slaves killed their masters and escaped. Crassus defeated the slave

army and crucified more than six thousand of them along the Appian Way. Caesar

sought to outdo his two colleagues by conquering northern Gaul.

Since their near-conquest of the city in 390

B.C.

, the Gauls had done little to

harm the Romans for several centuries. The Celts and Germans who lived in the

Gaul of Caesar’s time were civilized, comparably prosperous, and even wore pants

(while Roman men still wore skirts). They already interacted with the Græco-Roman

Mediterranean culture, supplying agricultural products and slaves captured in wars

between the tribes. Several tribes had even agreed to defense treaties with Rome.

When the Helvetii (ancestors of the modern Swiss) tried to move through a territory

of a tribe allied with Rome, those Gauls asked for Roman help.

Caesar seized the opportunity to expand Roman dominion, enhance his reputa-

tion, and win wealth (see map 5.1). For eight years, from 59 to 50

B.C.

, Caesar

exploited the fighting among different Celtic tribes to conquer Gaul (and even

briefly to invade Britain). Although the integration of the Celtic Gauls into the

Roman Empire would take several generations, Caesar wrote a book about his ‘‘suc-

cessful’’ conquest, The Gallic War, to make sure people realized what a good leader

he was.

With his fame established, Caesar turned to his real aim: leadership in Rome.

He declared his intentions of becoming sole dictator by leading his army from Gaul

into Italy in 49

B.C.

His crossing of the river Rubicon (now a metaphor for an irrevo-

cable decision) set him at war with his former allies and the Roman constitution

itself. Inevitably, might made right. By 46

B.C.

Caesar had defeated his rivals and

become dictator. He built on his success by adding Egypt to Rome’s dominions

through his intervention on behalf of its queen, Cleopatra, who had been quarrel-

ing with her brother over sharing power. Caesar’s sexual and political alliance with

Cleopatra gave him control over Egypt, the breadbasket of the Mediterranean.

Like the better Greek tyrants, Julius Caesar did not rule solely to satisfy his

own lust for power; he also addressed real problems. He carried out land reform,

especially by rewarding his veterans with confiscated property. He extended Roman

citizenship to conquered peoples in Gaul and Spain, improved the administration,

PAGE 80.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:28:39 PS

IMPERIUM ROMANUM

81

lowered taxes, and built public works such as aqueducts, baths, and temples. He

even made sense out of the seasons through his reform of the calendar. Caesar’s

Julian calendar gave us the basic system of twelve months and a periodic leap year

that we use now (although the Roman September through December were their

seventh through tenth months, as their Latin translations indicate).

Caesar’s enemies either envied his success or feared that he might make himself

king. The Romans had disliked kingship ever since they had rebelled against Etrus-

can kings at the beginning of their republic. For some, a monarchy undermined the

core of Roman identity. So a handful of senators plotted to assassinate Caesar.

During the ides (the middle of a month) of March in 44

B.C.

, as he entered the

Senate’s meeting place, they stabbed him twenty-three times.

Yet this political murder still did not resolve the problem of how to govern

Rome. Immediately, another war broke out over Caesar’s legacy, about who could

inherit his mantle. Caesar’s assassins were quickly discredited and killed. Among

his allies, the leading candidate was at first Marc Antony, Caesar’s lieutenant (known

today by the speech that Shakespeare put in his mouth: ‘‘Friends, Romans, country-

men, lend me your ears. I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him’’). But Marc

Antony had fatefully taken up with Caesar’s paramour Cleopatra. Many Romans

disapproved of the queen of Egypt, who was too Greek and too female. Instead,

Caesar’s grandnephew and adopted heir, Octavian, won the struggle for power. In

the course of several years of warfare, Octavian grew into leadership until he had

utterly destroyed all rivals, including Antony and Cleopatra. With this takeover, the

last Hellenistic kingdom formed by Alexander’s generals ended its independent

rule. By 27

B.C.

, Octavian ruled over an empire that came to symbolize Roman great-

ness. With the civil wars largely ended, the empire entered the period called the

Pax Romana—a period of peace and prosperity maintained by Roman power.

Octavian replaced the Roman Republic’s form of government with his own ver-

sion of absolutism, which historians call the Principate (27

B.C.

–

A.D.

284) (see dia-

gram 5.1). The new master of Rome was smart enough not to repeat his late uncle’s

mistakes. He vigorously professed modesty and a reluctance to assume power.

Octavian claimed to restore the order and stability of the old republic and refused

the title of king. Instead, he merely accepted the rank of ‘‘first citizen’’ or princeps

(from which we derive our word prince, a powerful ruler, not only the son of a

king). The republic’s name lived on, since officially the Senate and People of Rome

(SPQR) retained their traditional government roles.

Despite his humble platitudes, Octavian really concentrated all power in his

own hands. His actions reveal another basic principle:

Sometimes politicians do the exact opposite of what they say

they are doing.

He continued to collect titles and offices, such as consul, tribune, and even pontifex

maximus, the head priest. To make sure he was not assassinated, he assembled an

PAGE 81.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:28:39 PS

82

CHAPTER 5

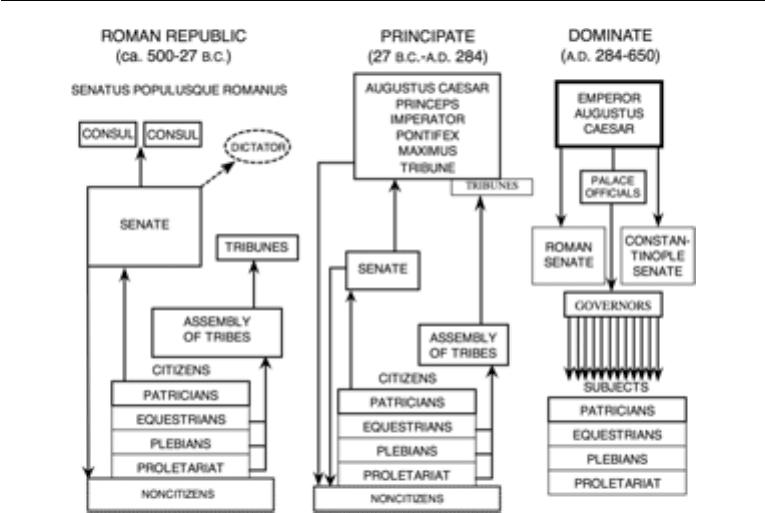

Diagram 5.1. Three Phases of Roman Government. After throwing out

the Etruscan kings, the Romans first established the Republic.

Representatives of the people worked through various governing

institutions, calling on a dictator only in case of emergency. Under the

Principate, the emperor’s power worked through surviving republican

institutions. With the Dominate, the overwhelming power of the emperor

reduced participatory citizens to obedient subjects.

unprecedented group of soldiers to protect his person, the Praetorian Guard. The

key to Octavian’s power was the office of imperator, or commander of the armed

forces (and from which we derive the word emperor). For the common people,

Octavian continued the reforming trends begun by Julius Caesar and set standards

of behavior and efficiency for the imperial bureaucracy (meaning rule by bureaus,

cupboards with drawers to store documents and records). Even the census called

by him was to promote efficient and fair taxation.

Senators authorized the changes that violated the old constitution. Octavian

granted to many of them a cut of the empire, although retaining for himself a large

share of the rule and profits of the overseas provinces. The Senators called Octavian

the father of the country and granted him the title Augustus (r. 31

B.C.

–

A. D.

14), or

‘‘honored one,’’ by which he is often known today. Indeed, both his family name

of Caesar and his honorific Augustus became synonyms for the word emperor. Even

more, he proclaimed the spirit of his ‘‘father’’ Julius Caesar as elevated to godhood.

Augustus Caesar, of course, shared in some of that divinity. Therefore, he began the

process of deification in Rome; the emperors became gods, as important for wor-

ship as the old civic mythological gods had been. The Romans thus imitated the

‘‘Oriental despots’’ of Persia, as Alexander had, harnessing godhood for political

stability. And so Augustus became the first Roman emperor.

PAGE 82.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:29:15 PS

IMPERIUM ROMANUM

83

Augustus’ system functioned well, but it possessed one great weakness: it was

based on lies. Rome, of course, had been an empire for centuries, based on its

rule of many different peoples. The republican labels survived, but the Principate

concentrated government in Augustus’ hands. Officially, Augustus pretended not to

be as powerful as a king or emperor, but everyone knew he was. The names ‘‘Cae-

sar’’ and ‘‘Augustus’’ disguised the face of authority. Since there was officially no

emperor, the Romans lacked a legal process for succession. As a consequence, the

emperor’s death raised problems.

Members of Augustus’ family, called the Julio-Claudian dynasty, used the lack of

clarity to continue their rule of the empire. Augustus’ first heir, Tiberius, brooded

in his sex den on the resort island of Capri while his lieutenant Sejanus almost

seized power. Just in time, Tiberius had Sejanus, his wife, and their young children

bloodily executed. The next emperor, Caligula, was probably insane, believing that

he had indeed become a god. Caligula named his horse to be a senator, raped

senators’ wives, and married his own sister before being murdered by his own

Praetorian Guard. Caligula’s older uncle Claudius survived to become emperor

because until Caligula’s death, everyone thought Claudius was an idiot. Although

Claudius ruled reasonably well, his third wife, Messalina, was a sex maniac, while

his fourth, Agrippina, probably poisoned him. Agrippina’s son, Nero, followed as

emperor and soon had his helpful mother assassinated. He proclaimed himself the

world’s greatest actor and forced rich and poor to sit through his awful perform-

ances of singing and strumming a lyre. He is infamous for ‘‘fiddling’’ while a good

part of the city of Rome burned, although he was probably innocent of that bad

behavior. He certainly did not play a fiddle, since it had not yet been invented. In

any case, fed-up Romans soon forced him to commit suicide.

Since Nero’s death in

A.D.

68 meant that all male heirs in Augustus’ dynasty had

died, the Romans fought a brief civil war in

A. D.

69, the year of four emperors. The

winner was the new dynasty of the Flavians, who started out well with Vespasian

and his elder son Titus. Each ruled briefly, with sense and moderation. Then the

younger son Domitian followed. He became increasingly paranoid and violent until

he was himself murdered in

A. D.

96. That Rome did not collapse into anarchy under

so many cruel and capricious rulers was a testament to its own vitality and the

success of the reforms made by Julius and Augustus Caesar.

The leaders who followed Domitian from

A. D.

96 to 180 have become known as

the Five Good Emperors. They secured Rome’s everlasting glory. The great eigh-

teenth-century historian of Rome, Edward Gibbon, credited the greatness of Rome

to the wise and virtuous reigns of Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Mar-

cus Aurelius. Trajan gained the last major province for Rome, exterminating the

people of Dacia, north of the Danube River by the Black Sea. The Romans who

replaced them later created the Romanian language.

While Gibbon certainly exaggerated, ancient Rome during this time has always

been attractive to readers of history as a Golden Age. Rome flourished by providing

a structure for political peace while allowing substantial cultural freedom. The

empire of this period stood for universalism—‘‘all is Rome’’—but the emperors did

not crush particularism. People worshipped diverse gods and deities, wore their

PAGE 83.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:29:15 PS

84

CHAPTER 5

own ethnic fashions, and ate their exotic cuisine. The Roman urban culture, fos-

tered by planting colonies of retired Latin soldiers, helped diverse peoples become

romanized to various degrees. Their previous cultures gradually and peacefully

faded as they adopted Roman social ways and the responsibilities and benefits of

citizenship. While some local ways of life faded away altogether, other regional and

ethnic diversity remained. The Romans advocated Latin as a language, yet every

educated Roman also spoke Greek. Many Greeks, who predominated in the eastern

regions of the empire, barely bothered to learn Latin. The protections of Roman

law increasingly covered non-Latins as citizens, until virtually everyone born free

within the borders of the empire could claim the privilege of Roman citizenship

(although it counted more for men than women). Even slaves had opportunities to

win their freedom.

Outside the Roman Empire’s borders, though, lived many peoples who did not

share in its riches and looked on in envy. The Romans had tried to conquer the

world in self-defense, but they did not succeed. Two of the empire’s borders

seemed secure. In the far north, much of Great Britain had been brought under the

Roman yoke in the first century

A. D.

Yet the ferocious Picts in the island’s north

stopped Roman advancement. Giving up the idea of invading the highlands,

Emperor Hadrian built a wall across the island to separate and defend the Roman

province from the wild northerners. The Celts on the island of Hibernia (Ireland)

were not even considered worth conquering. These two free peoples, though,

hardly threatened the empire’s interests. Likewise, on the border in the south, the

Sahara desert provided a natural barrier to the rest of Africa. Most of Rome’s other

borders, however, remained dangerously vulnerable. Slow communications meant

responses to emergencies took much too long.

The first major threat lay along the empire’s border through the heartland of

Europe. There the Germans or Goths dwelt in the dark woods and resisted subju-

gation by Rome. The Romans categorized the Germans as barbarians. They were, in

the sense that the Germans did not live in organized fashion around cities and

empire. Instead, they remained in loose and quarreling pastoral and agricultural

tribes along Rome’s central European borders. They sometimes traded, other times

raided to gain Rome’s luxury goods. They pursued comparatively egalitarian lives,

enjoying hunting and warfare.

Under Augustus, the Germans had already dealt a major defeat to Roman ambi-

tion. One memorable German leader, called Arminius in Latin (Hermann in Ger-

man), knew Roman ways from his life as a soldier who rose through the ranks in

the empire. Back in his homeland, Hermann led his people to ambush and slaugh-

ter three Roman legions in the Teutoburger Forest in

A.D.

9. Consequently, Augustus

called for the later Romans to refrain from further expansion in that direction. The

Romans eventually built a line of defensive fortifications, the limes, along the Rhine

and Danube Rivers, trying to fend off what they could not take over.

The second threat to the Romans was the Persians. By the first century

B.C.

, the

Romans had conquered the Greeks from the west. At the same time, the Parthians,

horse-riding archers from the Asian steppes, seized the Persian Empire from the

east, toppling the last of the Seleucid Hellenistic dynasts. The rich Mesopotamian

PAGE 84.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:29:16 PS

IMPERIUM ROMANUM

85

heartland of civilization lured both the Roman and Parthian/Persian empires. Held

off by the Parthians at first, the Romans had occupied Mesopotamia by early in the

second century

A.D.

Yet the Romans failed to defeat Persia as Alexander had.

Thus, Rome could no longer expand, limited by the Germans in Central Europe

and the Parthian/Persians in the Middle East. Failure to defeat the Germans and

Persians marked the Romans’ doom. Only the internal rivalries among both the

German tribes and Parthian elites as they fought one another postponed for a few

decades any catastrophic confrontations with Rome.

During this pause, as the second century

A.D.

wore on, preservation of the

Roman Empire became more necessary than expansion. First foreign threats and

then internal weakness brought on crises that threatened to tear the Roman Empire

apart, as had almost happened in the civil wars of the first century

B.C.

The office of

emperor finally failed to preserve the functioning of the bureaucracy. The Five

Good Emperors also did not solve the problem of finding a successor emperor. The

first four of those five emperors, who had no sons, did implement a policy of adop-

tion and designation, which showed promise. The reigning emperor sought out a

good, qualified successor and then adopted that person as his heir. This imitation

dynasty borrowed the stability of family rule to ensure talented leadership. Tragi-

cally, in

A.D.

180, Marcus Aurelius’ son, Commodus, inherited the empire from his

father. This end to the successful policy of adoption and designation was bad

enough, but Commodus’ insanity (combining paranoia with the belief that he was

Hercules incarnate) was catastrophic. Conspirators assassinated him, launching a

series of briberies, murders, and war over imperial power. Plague also ravaged the

empire, reducing the ability of Rome to recruit and pay for soldiers.

Then, in the late second century, the Germans and Persians attacked. In Central

Europe, the Germans invaded across the limes. Clumsy Roman interventions in

Mesopotamia allowed the native Persian Sassanian dynasty to replace the weakened

Parthian rulers of the Persian Empire and revive its power. In the Middle East, the

Sassanian-led Persians aggressively pushed the Romans back toward the Mediterra-

nean.

This time, when Rome requi red c apa ble leader ship, it had n one. Just as dur-

ing the collapsi ng republ ic of the second centur y

B.C.

, experienced Roman gener-

als were too busy fighting one another over control of Rome. Unfortunately for

political s tabi lity, generals have rarely been succ essful as pol itic ians . Con stan t

violence crippl ed im peri al authority. In t he fifty years betwe en

A.D.

235 and 2 84,

emperors se rved an av erag e of two y ears , with onl y two dyin g na tura lly and peace-

fully i n their beds. T he ‘‘barbarian’’ Germans actua lly cut d own one ‘‘civilize d’’

emperor in battl e, while the Persi ans c aptu red a nd enslaved a noth er. Such humil-

iations deeply s hocked the proud Roman s. Even worse, rampaging German s

sacked Roma n cities. Trad e suf fer ed, ur ban life cracked, and regions looked to

local leade rs fo r organizatio n an d def ense . Many towns hurri edly built walls,

believing the fa r-off emperor could no t help. The Roman Em pir e almost f ell apart

in the third century

A. D.

Then, in

A.D.

284, one more general, Diocletian (r. 284–305 ), s eize d the

throne.Asthesonofafreedman(amanumittedslave),hehadworkedhisway

PAGE 85.................

17897$

$CH5 10-08-10 09:29:16 PS