Pavlac B.A. A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities throughout History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

56

CHAPTER 4

To prevent a successful slave rebellion, the Spartans therefore organized their

entire state around militarism and egalitarianism, claiming that these values were

an ancient tradition. Egalitarian values meant that all citizens were to be rigorously

equal. For example, the government divided up the agricultural plantations in rela-

tively equal portions for each family. Money was made of large iron weights, which

were too difficult to store, spend, or steal. Trade and artisanship in luxury goods

was discouraged, since it would have increased the display of wealth. The common

good (for the elite minority) was seen as better than the individual good.

More famous has been the Spartan commitment to militarism. All men were

organized into military service. Male children were taken away from their parents

at the age of seven, and from then on they were raised in a military barracks. As

part of their training, they were encouraged to be stealthy and steal food from the

local population. If an adult caught a boy stealing, he could beat the young one,

sometimes so harshly that the boy died. At eighteen, a man who survived was

allowed to marry. Even then, a husband ate meals in the warriors’ mess until he

was sixty. Even on the wedding night, the husband had to return to the barracks

after consummation of the marriage. Women were esteemed if they produced male

children. Spartan parents often exposed female babies to the elements to die

because, as was common in the ancient world, they valued girls less than boys.

Likewise, the Spartans also tossed into a chasm any male infant whom a group of

elders deemed unfit for growing up to be a proper warrior. The public interest in

strong children overrode any parental rights or affections.

Sparta’s oligarchic government nevertheless functioned democratically, at least

for those few considered full-fledged citizens. No one person could be all-powerful.

At age thirty, men became citizens with full political rights. Two traditional kings

ruled Sparta as a pair, but they were really figureheads—real power rested with

appointed magistrates and a council of elders (about thirty of the leading citizens

over age sixty). Generations of Spartans tried to maintain this system with as little

change as possible because for them it embodied the virtues of the past and their

founding father, Lykurgus. When a political crisis arose, those who promoted a

policy always tried to claim, ‘‘It’s what Lykurgus would have wanted!’’

As a contrast in almost every way to Sparta, Athens developed democracy in its

purest form. When we think of the civilization of ancient Greece, we usually think

of Athens. The Athenians emphasized individualism rather than Sparta’s egalitarian-

ism and militarism. Athenian society encouraged its citizens to excel in politics,

business, art, literature, and philosophy, according to their talents. Athens’ location

on a broad fertile plain with easy access to the sea allowed its inhabitants a prosper-

ous economy and a large population. From early on, Athens faced the basic prob-

lem of resolving differences among three different constituencies: those of the city,

those of the plain, and those of the hills. Each had different priorities and loyalties.

These divisions hindered the formation of a more democratic form of govern-

ment until a series of tyrants began reforming the system. Draco, one of the first

tyrants, became infamous for his set of laws issued in 621

B.C.

Many of the laws

mandated the death penalty, even for minor crimes. Consequently, his name has

become a byword for excessive harshness: draconian. A few years after 600

B.C.

, the

tyrant Solon solved so many problems that his name became a byword for political

PAGE 56.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:42 PS

TRIAL OF THE HELLENES

57

wisdom. To stop unrest, Solon divided the people into classes based on property,

canceled farmers’ debts outright, and expanded citizenship to the poor. Finally, by

about 500

B.C.

, Cleisthenes left a substantially democratic structure in place.

Cleisthenes’ balanced constitutional system served Athens for most of the fifth

century

B.C.

First, Cleisthenes brought all citizens together into a political body

called the Assembly. As the supreme legislative body, it included all male citizens

over eighteen, about 10 percent of the population. Anyone was allowed to speak

and vote, and a simple majority decided most issues. The Assembly declared war,

made peace, spent tax money, chose magistrates, and judged capital crimes. Thus

every citizen was involved in making the most important state decisions. How was

the citizen to make up his mind how to vote in the Assembly? Politicians became

orators, speech makers, striving to sway the crowd. If a politician became too pow-

erful, the citizens could impose ostracism. The ‘‘winner’’of a vote made with politi-

cians’ names on pieces of broken pottery (ostrakons) was sent into exile. To prevent

such votes and hold onto power, politicians built up factions, groups of followers

on whom they could rely. In Athens, as in most city-states, one faction tended

toward democracy, the other toward oligarchy.

The Assembly met only periodically. Select citizens carried out the day-to-day

administration of the city. Interestingly, the Athenians filled most administrative

positions by lot: a chance name drawn from a barrel. They reserved actual voting

within each tribe (ethnos) for elections of generals (strategoi, from where we get

our word strategy). An advantage was that election ensured the generals had the

support of their troops. They could hardly disobey someone they themselves had

elected. A disadvantage was that soldiers did not always elect the best strategists or

tacticians. Popular charisma is not always the best quality in battle. From the point

of view of the city’s leaders, though, dividing power among ten commanders pre-

vented any one general from possessing too much military power.

Cleisthenes’ second innovation aimed to end old feuds between people living

in different geographic regions. He broke up loyalties by creating new ties that were

not based on blood or status. He divided each of the three regions (city, plain, and

hills) into ten districts. One district from each of the three regions was then com-

bined into a new ‘‘tribe,’’ artificially forcing the divergent people of city, plain, and

hills together. These tribes determined a citizen’s role in the rotating administration

and military service. Finally, the ten tribes sent fifty representatives each to the

Council of 500. This important body prepared bills for the Assembly, supervised

the administration and magistrates, and negotiated with foreign powers.

The Athenian democratic idea, as we shall see in later chapters, would endure

and continue to inspire change, even violent revolutionary change, up to the pres-

ent day. Nevertheless, throughout most of Western history, cultural conservatives

have attacked democracy and democratic tendencies. Indeed, most Hellenes them-

selves admired and claimed to prefer the oligarchic Spartans to the democratic

Athenians. It seemed less messy to have a more authoritarian system of government.

The chaotic debate and passions of the Athenian crowd seemed undignified com-

pared with the stoic calm of Spartan deliberation. As both city-states entered confi-

dently into Greece’s Classical Age (ca. 500–338

B.C.

), this whole argument was

nearly lost to history (see timeline 4.1). Just as these early experiments in self-

PAGE 57.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:44 PS

58

CHAPTER 4

government had begun, the most powerful empire of the age nearly wiped them

out.

Review: How did the Greeks attain degrees of democratic politics?

Response:

METAMORPHOSIS

The Greeks almost vanished as a people because the emperor of the vast and pow-

erful Persian Empire decided to crush them. Instead the Greeks metamorphosed,

their word for transformed, into a political power to be reckoned with. The first

stage of this transformation was their defeat of the Persian invasions. After that,

however, they nearly defeated themselves. Finally, they regrouped under new lead-

ership to invade and conquer Persia itself.

As seen in the previous chapter, by 500

B.C.

Persia’s power covered most of Asia

Minor, where many Greeks lived. Although the supreme rule of the shah satisfied

most of his diverse subjects, the independent-minded Greeks chafed under the

absolutist Persian yoke. The Greeks put the conflict in simple terms: freedom versus

servitude. In 499

B.C.

, many Greeks in Ionia rebelled against their Persian imperial

masters and burned a provincial capital. The Persians simply saw arson and violent

rebellion. In retaliation, Persian troops burned the Greek cities in Ionia and

enslaved their residents. Then Emperor Darius found out that the rebels had

received help from across the Aegean, from the Athenians and a few of their fellow

Greeks. Obviously, these supporters of rebels needed to be smashed, so Darius

invaded Greece. Thus began the Persian Wars (494–449

B.C.

).

In 490

B.C.

, the Persian forces landed about twenty-four miles east of Athens,

near the village of Marathon. The story of a messenger who ran to the Spartans for

aid soon grew into the myth of the heroic marathon runner who delivered his

message with his dying breath. The distance from Athens to Marathon has given us

the modern Olympic race, although the Greeks themselves never ran such a long

distance in sport. Surprisingly, the Athenians did not actually need help from the

militaristic Spartans. The Athenians and a few allied forces of hoplites managed to

push the enemy back from the beaches into the sea, even though the Persian land-

ing force was twice their number.

PAGE 58.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:45 PS

TRIAL OF THE HELLENES

59

Ten years later, Darius’ successor, Xerxes, decided to avenge his father’s defeat,

especially after the Greeks sparked a revolt against Persian imperial rule in Egypt.

Xerxes amassed the largest army that had ever been assembled, reportedly several

hundred thousand troops from all corners of the diverse empire (and including

Greeks who had submitted to his authority). To avoid the dangers of a sea-to-land

invasion, he built a bridge across the narrow straits of the Dardanelles that sepa-

rated Europe from Asia. As the Persian army marched into Greece, most Greeks

surrendered and begged for mercy.

Others, led by Athens and Sparta, resolved to fight. Athens had built a major

fleet of triremes, financed by a recently discovered silver mine. Sparta, of course,

had the best hoplites, but a majority of its leaders refused to commit themselves to

a common defense. So out of a possible army of eight thousand, only a small force

of three hundred Spartans, joined by several hundred hoplites from other city-

states such as Thebes and Thespia, advanced to hold off the advancing Persian army

in the pass at Thermopylae. Mountains protected the Spartans’ left flank, and the

Athenian navy supported their right. After a few days of heroic resistance, some

Greeks led Persian forces along a mountain path behind the Spartan line. The Per-

sian army surrounded and slaughtered the Spartans. The outnumbered Athenian

and allied navy, which had also fought well against the Persians, withdrew.

With the road now clear of opposing armies, all of Greece lay open to annihila-

tion. The Persian army marched into Athens, only to find it abandoned. Xerxes set

fire to the city and waited for his fleet to bring essential support to his troops. Then,

as the Persian fleet entered the straits of Salamis, the Athenian and allied Greek

navy sprang a surprise attack. Crammed into the narrow strait and confused, the

Persian captains panicked. One Persian captain, Queen Artemisia of Halicarnassus,

attacked her Persian allies in order to retreat. Xerxes had to withdraw. He invaded

again the next year, but the Greek phalanxes defeated his army at Plataea. The puny

Greeks had beaten the greatest empire in the world.

The Greeks portrayed their victory as the success of liberty and civilized virtue

over oppression and barbarian vice. We might, however, exercise some caution in

fully embracing their enthusiasm. Remember, the Persians had maintained a rela-

tively tolerant empire. They had allowed the Jews to resettle Palestine. They had

created general prosperity and stable rule with which many of their subjects were

satisfied. If the Persians had won, some sort of Western civilization still might have

developed. Perhaps the Persians could have gone on to conquer the rest of Europe.

Or maybe the Romans or Phoenicians could have stopped and reversed the Persian

advance. In any case, the Greek triumph did not guarantee success for their versions

of liberty and virtue. They would betray those values themselves.

Buoyed by victory for the moment, the Athenians entered their brief Golden

Age, which lasted only fifty years, from 480 to 430, less than one lifetime. A new

literary genre was invented to celebrate: history. Two famous books frame that age:

one describes the war that enabled the Golden Age, the other the war that ended

it. Both are early examples of historical writing since they relate how human choices

rather than divine intervention drove events. First, Herodotus of Halicarnassus

wrote his History, a retelling of the Persian Wars, for which he is considered the

father of historical writing. Herodotus developed that theme of Europe versus Asia,

PAGE 59.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:46 PS

60

CHAPTER 4

the Hellenes against the barbarians. Second, Thucydides wrote a history of a civil

war fought by Greeks against Greeks, now known as The Peloponnesian War. Thu-

cydides was an even better historian than Herodotus, insightfully examining events

and evenhandedly assigning fault or merit to the historical players. He also reimag-

ined dialogues and speeches made by leading and representative participants. Such

dramatic invention is not like the fact-based writing of modern historians, but it

makes for great reading.

To some extent, the Peloponnesian Wars (460–404

B.C.

) inevitably followed

from Greek particularism. Each polis pursued its own aims, usually without regard

for the greater good of all Greeks. At the heart of these differences was the contra-

diction between the ideologies of Athens and Sparta. Democratic Athens looked

outward and reveled in culture. Oligarchic Sparta gazed inward and worked at disci-

pline. Could two such different cultures coexist in the same civilization? At first, the

necessity of the Persian threat demanded it. After the defeat of the Persians at the

Battles of Salamis and Plataea, many Greek poleis remained together in an alliance

dedicated to the final defeat of Persia and the liberation of the Ionian Greeks. This

Delian League had its original headquarters and treasury on the Aegean island of

Delos. All too soon, however, the Athenians manipulated the Delian League to sup-

port their increasing domination. In most of the key battles, the Athenians bore the

brunt of the fighting because they had the largest war fleet. For them, this sacrifice

fully justified their new supremacy among the Greeks. Athenian culture was enor-

mously expensive and cost far more than what the city-state of Athens produced.

Thus, the Athenians extracted tribute from the other poleis to pay for the navy and

troops. The other states submitted to Athens because they, like most people, were

willing to let others fight for them.

Soon Athens had ceased to be a mere city-state—it had become an empire. In

455

B.C.

, the Athenians ceased all pretense about their own imperial ambitions and

moved the league’s treasury from Delos to Athens. Even after Persia officially made

peace with the Greeks in 449

B.C.

, the Athenians maintained their supremacy. When

member poleis tried to withdraw from the Delian League, Athens took over their

cities. If nonmember poleis threatened Athenian power and prosperity in any way,

Athens attacked them. Thus, Athens began to achieve political unity for the Greeks

through domination. In their own eyes, they deserved to be the leaders of the

Hellenes. Not for the first time would a people practice democracy at home yet

imperialism abroad.

The leader of Athens toward the end of this Golden Age was Perikles (b. ca.

490–d. 429

B.C.

). Perikles rose to power as the leader of the democratic faction,

based on a reputation for honesty and skill in public speaking. He wanted to use

the imperial wealth to subsidize the lower classes of Athens. For example, he

arranged for jurors to be paid, thus enabling simple laborers to take time off from

their jobs to hear cases. Those in the oligarchic faction of well-born gentlemen

considered their social inferiors to be a worthless mob. The oligarchs even resented

the building of the Long Wall to protect the city and its port. The expensive project

may have protected the homes of vulgar commoners, but it left the oligarchs’ fields

outside the walls defenseless. The oligarchic faction tended to see Perikles as head-

ing toward tyranny for himself. Since they could not attack Perikles directly, they

PAGE 60.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:47 PS

TRIAL OF THE HELLENES

61

tried to discredit him by bringing corruption charges against those close to him, the

sculptor Phidias and his mistress Aspasia (a former hetaira, or high-class prostitute/

courtesan). Both factions in Athens, though, generally supported Perikles when he

proudly rebuilt the city after the Persian devastation with glorious marble temples

paid for with the profits of empire.

Other Greeks opposed the Athenian supremacy. Sparta formed a rival Pelopon-

nesian League, which saw Athenian expansionist policies as a threat to liberty as

bad as that of the Persians. Corinth, though, began the First Peloponnesian War

when it attacked Athens in 460 to stop its expansion. Spartans soon joined in.

Neither side, however, fully committed itself to decisive victory because the Spar-

tans were putting down revolts by helots and the Athenians were still fighting the

Persians. The two sides signed a thirty-year truce in 445

B.C.

It lasted only half that

long, as mutual hostility between the Spartan and Athenian alliances continued to

grow worse. In 431, when some of the allied states began fighting one another,

each side thought the situation serious enough to declare war. Each city-state was

confident in the virtue of its vision and its arms.

These Peloponnesian Wars were the greatest tragedy for Greece. At first, neither

side could effectively fight the other. The Spartans dominated with infantry, but

they could not breach the high, long walls enveloping Athens. The Athenians ruled

the waves, but they could not land enough infantry to defeat Sparta. The strategy

backfired early for the Athenians, when plague struck the crowded, besieged city in

430

B.C.

It killed Perikles by the next year, and no successor shared his qualities of

statesmanship.

In arrogant bids for supremacy, both Athens and Sparta attacked neutral states,

thereby forcing all Hellenes to choose sides. Each side basically told other Greeks,

‘‘You can have liberty, but only on our terms.’’ In a famous example, the polis of

Mytiline tried to secede from the Delian League after Athens had been weakened

by the plague. In 427

B.C.

, the recovered Athenians decided to punish the Mytilines

by killing every male and selling the women and children into slavery. They had

second thoughts, however, and killed only a thousand of Mytiline’s men. Such polit-

ical slaughters by winners on both sides piled upon the casualties from battle and

disease. Class conflict also increased as Sparta supported oligarchic factions in vari-

ous poleis and Athens encouraged democratic factions. Rather than solve their dis-

agreements in political dialogue and vote, extremists took to violence, assault, rape,

arson, and murder. So Greek political structures were attacked from both without

and within.

A truce in 421

B.C.

might have ended the war while the Greeks were still strong

enough to recover. The Athenians, however, showed themselves to be addicted to

power. Thucydides described the Athenian attack on the neutral island city-state of

Melos in 416

B.C.

The Melians appealed to the Athenians to leave them in peace.

The Athenians demanded surrender, defending their supremacy with the harsh

reality that stronger societies always dominated weaker societies. As promised, the

Athenians defeated the Melian forces. Showing no mercy as they had to the Myti-

lines, the Athenians killed all the adult males on Melos and enslaved the women

and children.

Even worse, the Athenians made a grave mistake by pushing their imperial

ambitions too far in a poorly planned and unnecessary attack. Led by the young

PAGE 61.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:48 PS

62

CHAPTER 4

politician Alkibiades, a majority agreed to outflank the Spartans at sea by establish-

ing power in Magna Græcia, on the island of Sicily. They used the excuse of helping

an allied polis that had complained of oppression by the great city-state Syracuse,

the key to the Western Mediterranean. In 415

B.C.

, the Athenians landed and found

a well-prepared enemy and few allies. Instead of withdrawing or gaining a quick

victory by assault, the Athenians tried to build a wall to cut off the Syracusans and

starve them out. Meanwhile the Syracusans built a counterwall to isolate the Atheni-

ans, who all too soon ate and drank all their supplies. For two years, the Athenians

were bogged down in a faraway land until their best warriors were killed and thou-

sands more cruelly enslaved to die digging in quarries. Athens lacked the resources

to recover from this defeat. The ostracized Alkibiades fled first to Sparta and finally

to Persia. Sparta itself finally counterattacked with its own new navy, built with the

help of its old enemy and new ally, Persia. The Spartans cut off supplies to Athens

by both sea and land, forcing the city to surrender in 404

B.C.

Sadly, neither peace nor prosperity followed. Persia stoked the mutual suspi-

cions of the Greeks against one another. Sparta began to act as imperialistically as

Athens had. The city-states of Thebes and Corinth attacked their former ally Sparta.

Then the Greek helot-slaves of Sparta successfully revolted. The once-mighty Sparta

declined into an obscure village of no account. Meanwhile, Corinth and Thebes

were each too weak to hold new empires of their own. Everywhere, demagogues

(partisan public speakers) inflamed emotions and manipulated public opinion

toward short-term thinking and factionalism, or opposing groups’ refusal to coop-

erate with one another. Class warfare worsened. Thus, the Greek polis failed politi-

cally. Democracy proved to be too difficult.

A political solution to this chaos came from the north: old-fashioned kingship.

The kingdom of Macedon lay along the mountainous northern reaches of Greek

civilization. The southerners had always disregarded the rustic Macedonians as too

insufficiently civilized to be true Greeks. The Macedonians did not live in cities;

they spoke with poor accents; and they had been weak politically. That changed

with King Philip II (r. 359–336

B.C.

). As a youth, he had been held hostage in the

polis of Thebes. While classical Greek culture impressed him, its political capabili-

ties did not. He returned to Macedon, reformed the administration of his kingdom,

and strengthened his army along Greek lines. He also added cavalry to defend the

sides and rear of a more flexible Macedonian phalanx and improved siege machin-

ery to take city walls. Armed with these advantages, Philip began his conquest of

Greece, taking city-state after city-state. At the Battle of Chaeronea in 338

B.C.

, Phil-

ip’s army crushed the last Greek resistance to his rule on the mainland. He was

now hegemon, captain-general-ruler of the Greek world (from which we get the

word hegemony for political supremacy). The Hellenistic Age (338–146

B.C.

) sup-

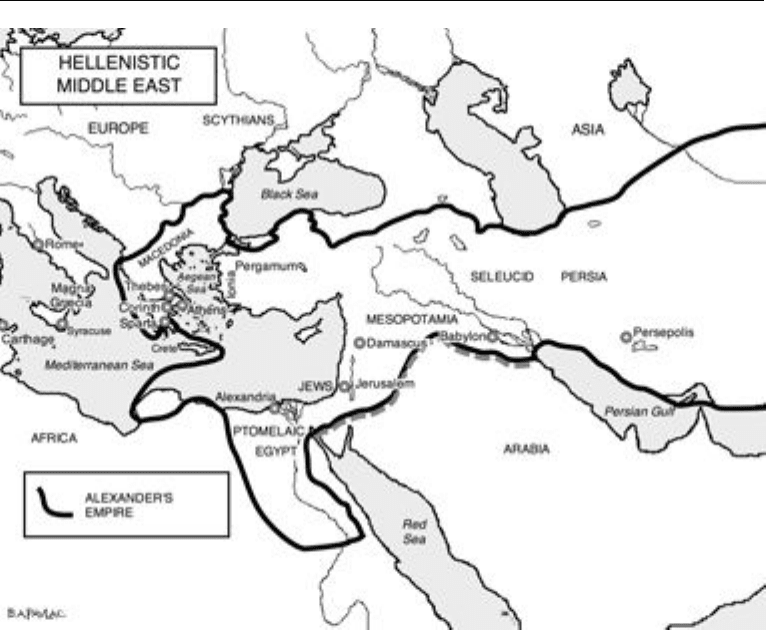

planted the Classical Age of Greece (see map 4.1).

Philip was assassinated at the height of power, perhaps because his wife, Olym-

pia, and his son, Alexander, were behind his murder. The new twenty-year-old King

Alexander III (r. 336–323

B.C.

) soon gained the title ‘‘the Great’’ for his conquest

of much of the known world. As one of the greatest generals who ever lived, Alexan-

der carried out his father’s proposal to attack the age-old enemy, Persia. His Mace-

donian and Greek armies routed the Persian forces in Asia Minor, liberated Egypt

from Persian imperial power to put it under his own, and then swept through

PAGE 62.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:48 PS

TRIAL OF THE HELLENES

63

Map 4.1. Hellenistic Middle East

Mesopotamia to take Iran itself. So awed were people, and he himself, by his suc-

cess that deification began, the belief that a person became a god. Alexander did

not discourage the trend and may have believed in his divinity himself.

Whether Alexander ‘‘the Great’’ was god, emperor, general, or fool, his soldiers

followed him farther eastward into the foothills of Afghanistan and into the Indus

River valley. Only the fierce resistance by the vast populations of the Indian Subcon-

tinent finally allowed his soldiers to convince the not quite thirty-three-year-old

Alexander to turn back toward Greece. On the way, after a night of heavy drinking,

Alexander fell into a fever. A few days later, whether from too much alcohol, infec-

tion, or poison, the conqueror lay dead.

Review: How did the Greeks enter a brief Golden Age, and how did it collapse?

Response:

PAGE 63.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:27:21 PS

64

CHAPTER 4

THE CULTURAL CONQUEST

Opinions about the rise of Macedonian power stir controversy. Critics of Philip and

Alexander condemn their use of conquest, destruction of democracy, and overem-

phasis on the cult of personality. Supporters praise their heroism, reform of govern-

ment, and unification of Greeks among themselves and with other peoples.

Alexander had even encouraged his Greek soldiers to marry Persian women.

Regardless, Philip and Alexander’s brief reigns changed history for the Greeks and

all their neighbors. The Hellenistic Age saw Greek power reach diverse peoples

across the ancient world. The great cultures of Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Persia

collapsed before the armies of Alexander.

Although the political unity of Alexander’s empire died with him, the Greeks

stayed on as regional rulers. They founded new poleis and colonies of Greeks

throughout their kingdoms. Greek became the common language, and Greek prac-

tices dominated economics, society, and the arts. The conquered peoples adapted

to Greek civilization in a process called hellenization. Eventually, being Greek

became a cultural attitude, not solely a physical descent from the forefather Hellas.

The classic political democracy, though, was not part of this expansion, since

democracy lay in ruins. Ending the give and take of political debate, Alexander

imposed absolutism. Like other Middle-Eastern semidivine potentates, the Hellenis-

tic kings employed deification with elaborate rituals emphasizing their similarity to

the gods. Thus, the manner of ‘‘Oriental despots’’ entered Western civilization.

Alexander’s successors were generals who seized power and set up dynasties. In

the constant tension between independent local control and centralized authority,

the city-state vanished under the Hellenistic monarchs.

Alexander’s brief empire fell apart into three great power blocs. One general

took Macedon and from there tried to impose Macedonian rule on the Greeks of

the south. Another, Ptolemy, seized Egypt, whose rich farmlands and ancient heri-

tage provided the most secure and long-lasting power base. A third, Seleucis, con-

trolled the riches of Asia Minor and ancient Persia. The Macedonian, Ptolemaic, and

Seleucid dynasties dominated the Western Mediterranean and Middle East for about

two hundred years, until supplanted yet again by other rulers.

While the Hellenistic kingdoms failed to establish enduring political unity, they

fostered a cultural success that endured for many more centuries. The Greeks lost

political choices, but they gained a role in history that would have amazed even the

most optimistic Athenian of the Golden Age. Greek culture became the standard

for much of the ancient world as well as the foundation of Western civilization.

Most of that culture reflected Athens and its Golden Age of fifty years after the

Persian destruction of 480

B.C.

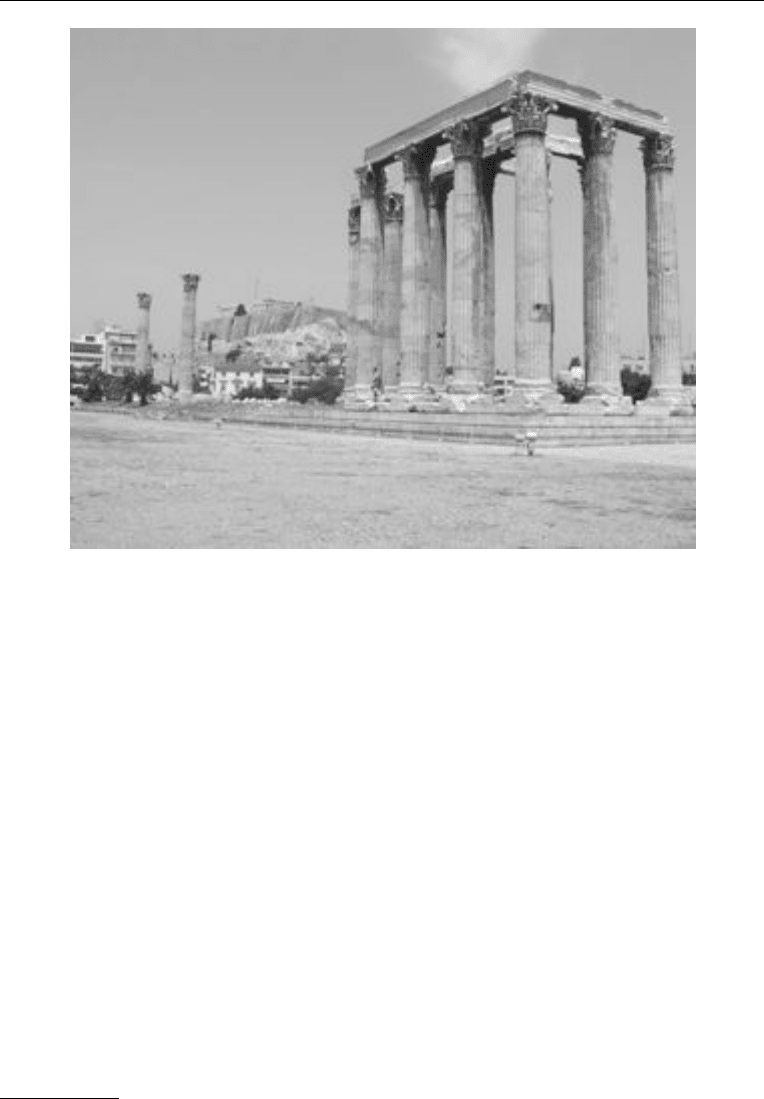

The Athenians rebuilt their ruined city in shining

marble. The crowning achievement was the temple atop the acropolis, the Par-

thenon, dedicated to the city’s namesake, Athena, the goddess of wisdom (see fig-

ure 4.1). It pleases the eye, perfectly proportioned and harmonious, while its

design contains nary a perfectly straight line in the Euclidian sense. The Athenians

decorated the Parthenon with the most anatomically correct sculptures done by

anyone in the West up to that point (although they usually painted the figures in

PAGE 64.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:27:22 PS

TRIAL OF THE HELLENES

65

Figure 4.1. The remains of the Temple of the Olympian Zeus, with the

Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens looming beyond.

garish colors that would strike us as strange and would horrify later art critics who

had learned to admire the shimmering white of marble).

1

The realism and natu-

ralism, mixed with a poised serenity, characterized the art of the Classical Age.

The effort spent on the temple of the Parthenon demonstrated again how reli-

gion was the heart of Greek society. The Greek myths and legends showed the

Olympian gods to be uninspiring from a moral or spiritual sense. The gods fol-

lowed anthropomorphism; they not only looked like humans but also behaved

like them, usually at their worst. For example, the ruler of the gods, Zeus, ruled as

a petty tyrant with his thunderbolts. He was notorious for his many affairs with

goddesses, mortal women, and even the occasional boy. Likewise, the beauty of

Aphrodite, the goddess of love, usually ruined men’s lives. The gods’ quarrels with

one another spilled over into human affairs, and they quickly avenged insults to

their divinity. Their divine interference is best recounted in Homer’s epic poems,

The Iliad and The Odyssey, mentioned earlier. The latter tells of a Greek king trying

to return home after the Trojan War. Because he offends the gods while trying to

survive, they throw many obstacles in his way: sirens, cyclopes, sorceresses, and

even suitors for his faithful wife, Penelope. The legendary Trojan War itself had

1. The Parthenon survived largely intact for almost two thousand years. In

A.D.

1687, during

a war between Venice and the Ottoman Empire, the Turks stored ammunition in the temple, and

a direct hit blew off the roof. In the early 1800s the British Lord Elgin took to England many of the

sculptures, which had been neglected by Turkish officials. The Greeks and the British continue to

argue about returning the originals.

PAGE 65.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:27:46 PS