Pavlac B.A. A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities throughout History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

46

CHAPTER 3

doom them. Their life under the Persian Empire was tolerable. The local governor

often gave way to the leadership of priests in local affairs. When the Persian Empire

fell in 330

B.C.

to Alexander (see the next chapter), Greek kings based in Egypt

or Syria ruled the Hebrews for several centuries, again allowing them substantial

autonomy.

That conquest by the Greeks began the last great turning point of Hebrew his-

tory, the Diaspora (dispersion or scattering). Both encouraged by cosmopolitan

freedom under other Greek rulers and oppressed in Palestine by their own, the

majority of Hebrews left their chosen home for distant lands to live among other

peoples. At this point, historians switch from calling them Hebrews to Jews. Within

an international cultural and political system dominated by Greeks, many Jews

found it easy to leave Palestine and settle in enclaves in distant cosmopolitan cities

throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East, even as far as India.

Jews who remained in Judaea found one more brief moment to claim their own

worldly kingdom. In 165

B.C.

, a Greek king desecrated the temple in Jerusalem in

honor of his own gods. In reaction, the Maccabee (or Hammer) family led a revolt,

winning about a century of independence again for the Jews. Then, in the first

century

B.C.

, Roman armies marched into the Middle East (see chapter 5). By 63

B.C.

,

the Romans had easily conquered the weak Jewish kingdom, although keeping

order among the Jews proved much more difficult. Recurrent Jewish revolts and

rebellions led the Romans to destroy the temple in

A.D.

70 and intensify the Dias-

pora by forcefully ejecting the majority of Jews from Palestine after

A.D.

135. From

that time until the twentieth century, most Jews lived outside of Palestine and had

no political autonomy of their own. They lived in small enclaves in the cities of the

kingdoms and empires of other peoples.

The Jews lost their kings, the temple and its priests, and their agricultural base

as they moved into foreign cities. Out of necessity, the Jews ceased to be peasant

farmers and became urban traders and merchants. Teachers trained in their scrip-

tures, called rabbis, came to lead Jewish communities instead of priests or kings.

Studies by rabbis were collected into the Talmud, which helped Jews interpret their

sacred scripture. Enough tolerance in the Hellenistic and Roman cosmopolitan

cities allowed the fragmented Jews to keep practicing their religion across the Medi-

terranean world.

Toleration went only so far, however. Most states have justified their existence

through a divine connection; thus a different faith implied a lack of allegiance. Jews

also remained a perpetual irritant for authorities who preferred conformity because

they were so often capable at maintaining their distinct religion. Outsiders often

resented the Jews’ view of themselves as the creator of the universe’s specially cho-

sen people. That perspective could be interpreted as excluding all others from

divine favor. As the Jews came under Roman rule, they annoyed their new overlords

by refusing to make religious sacrifices to the Roman gods, especially the emperor.

The Hebrew God was a jealous God and tolerated no worship of other deities.

Fortunately, the Romans recognized, in their usual tolerant matter toward religion,

that Judaism predated their own rituals. Abraham, Moses, and David had lived cen-

turies before the founding of Rome. So the Romans granted a special license to or

exemption for the Jews.

PAGE 46.................

17897$

$CH3 10-08-10 09:26:37 PS

THE CHOSEN PEOPLE

47

Despite this sympathy for differences, Jewish cultural identity has continuously

provoked hostility in their neighbors. Our modern word for this antagonism toward

Jews is anti-Semitism. Scholars coined the term just over a century ago as a polite

alternative to ‘‘hatred of Jews.’’ Through the centuries, that hatred has ranged from

mere dislike for Jews as ‘‘different,’’ to discrimination in jobs and housing, to vio-

lent persecution, and even to extermination. Had the Jews assimilated, given up

any unique clothing, religious practices, and ways of speech or life, then anti-Semi-

tism might have disappeared. But then Jews might have ceased to be Jews. Since

many Jews have remained faithful to their conception about how to obey God,

they have often faced difficulties with majorities who wanted them to conform or

convert.

The Jews survived as a small but significant minority in the ancient world of the

Middle East, Europe, and even deeper into South and East Asia. Compared with the

rise of the other ancient empires, the political history of the Hebrew kingdoms

mattered little. Ancient peoples likewise expressed little interest in the religion of

Judaism compared with the other raging currents of faith and superstition in the

ancient world. Nonetheless, the Jewish people have endured without a homeland

as only a few peoples in world history have done. As residents in the cities of Europe

they would contribute from their culture to the growth of Western civilization. Also,

out of their religion arose other beliefs that would shake the West and the world to

their foundations. Before those moments, however, two other Mediterranean peo-

ples added their own groundwork to Western civilization.

Review: How did the Jews maintain their cultural identity?

Response:

PAGE 47.................

17897$

$CH3 10-08-10 09:26:37 PS

PAGE 48.................

17897$

$CH3 10-08-10 09:26:37 PS

4

CHAPTER

Trial of the Hellenes

The Ancient Greeks, 1200

B.C.

to

A.D.

146

W

hile the ancient Hebrew kingdoms were oppressed on all sides by con-

querors, another people, the Greeks, were able to prosper far away from

dangerous conquerors, at least at first. Later, they would earn the wrath

of the most powerful empire of their age. Afterward, the Greeks could have been

utterly destroyed like the ‘‘lost tribes’’ of Israel or beaten into political impotence

like the last kingdom of Judaea. Instead, for a brief moment in history, the Greeks

triumphed to dominate the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. Yet a tragic

flaw in their success drove the Greeks into political irrelevance. Nevertheless, the

Greeks’ cultural achievements made them the second founding people of Western

civilization.

TO THE SEA

The Greeks called themselves Hellenes, the descendants of a legendary founder

named Hellas. They first came together as a people in the dark time around 1200

PAGE 49.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:39 PS

50

CHAPTER 4

B.C.

, when so many other civilizations had suffered crises at the dawn of the Iron

Age. Two of those civilized peoples, the Mycenaeans (who had lived at the southern

tip of the Balkan Peninsula) and the Minoans (who had been centered on the

nearby island of Crete) survived only through myths and stories of the Trojan War

(for the former) and the Minotaur of the Labyrinth (for the latter). At the beginning

of these Greek ‘‘Dark Ages,’’ the first Hellenes invaded and took over the southern

Balkans, displacing, intermarrying, and blending with the surviving indigenous peo-

ple to become the Greeks. They themselves distinguished three main ethnicities of

Dorians, Ionians, and Aeolians.

Although the Greeks remained loosely connected through their language and

culture, geography inclined them toward political fractiousness. Greece’s sparse

landscape seemed inadequate for civilized agriculture, compared with the vast fer-

tile plains of the Nile and Mesopotamian river valleys. The southern end of the

Balkan Peninsula and the neighboring islands in the Aegean Sea were mountainous

and rugged, with only a few regions suitable for grain farming. Grapevines and olive

trees, though, grew well there and provided useful produce of wine and oil for

export. Also, numerous inlets and bays where the mountains slouched into the sea

provided excellent harbors. Therefore, the Greeks became seafarers, prospering

less by farming and more by commerce, buying and selling, as they exchanged what

they had for what they needed. And if a little piracy was necessary now and then,

they did not mind that either.

The Greeks were so successful that by 800

B.C.

the southern Balkan Peninsula

and the Aegean islands had become too crowded. In the Greek homeland, the

Greeks lived without a king, divided into separate, independent city-states, each

one called a polis (in the singular; poleis in the plural). Elsewhere, though, good

farmland lay available for the taking. So the Greeks began a new form of conquest:

colonialism. In forming colonies, a crowded city-state would encourage groups of

families, as many as two hundred men and their dependents, to emigrate. The

Hellenes sailed across seas rather than merely crossing plains or rivers to conquer

neighboring lands. There, on some other island or distant shore with a good harbor

and a hill to build a fort, the emigrants would found a new city-state. Many indige-

nous peoples were killed, assimilated, enslaved, or driven away. Greek coloniza-

tion, however, differed from other imperialistic conquests, both in scale and

purpose. Greek colonies followed from small invasions, which did not bring in

royal or imperial domination. The Hellenes lacked a common king or emperor like

most other peoples had. Instead, the Greeks fostered political diversity. The new

colonies remained only loosely connected to their founding state. They became

free poleis, responsible to no higher political authority.

Most of these independent new colonies succeeded. The Greeks occupied all

the islands of the Aegean Sea, where they still live today. More Greek populations

settled in western Asia Minor (called Ionia), along the shores of the Black Sea,

and all around the Mediterranean. Their settlements survived for many centuries,

although people of Greek ethnicity no longer live in those places today (see chapter

14). By 500

B.C.

, more Greeks were actually living in the region of southern Italy

and Sicily, called Magna Græcia (or Greater Greece), than in the old Greek home-

PAGE 50.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:40 PS

TRIAL OF THE HELLENES

51

land. The colonies promoted trade networks and encouraged innovation and

invention as the Greeks built new homes and thrived in strange lands.

At the same time as the Greeks, the rival Phoenicians, a Semitic people, were

trading and colonizing in the Mediterranean region. The Phoenicians shipped out

from the Levantine coast, the eastern coastline of the Mediterranean that runs from

Asia Minor to Egypt. At first, they prospered and expanded more than the Greeks.

They clearly dominated the Western Mediterranean in regions untouched by the

greatness of Middle Eastern civilizations. Some Phoenicians sailed as far as Great

Britain, around the coast of Africa, and perhaps even to the Americas. The Phoeni-

cians gained an early advantage with their invention of the first alphabet. All previ-

ous and contemporary civilizations, Sumer with its cuneiform and Egypt with its

hieroglyphics (or, for that matter, China and India), used written systems composed

of thousands of symbols, many of which represented only one word.

Instead, the Phoenicians chose about two dozen symbols to represent sounds.

With these few symbols to signify consonants and vowels, they could spell out pho-

netically (from Phoenicians!) any word that could be pronounced. Most neighbor-

ing cultures, including the Hebrews, the Hellenes, and even the Egyptians, soon

adapted the Phoenician alphabet idea to their own use. Indeed, soon people forgot

how to read cuneiform or hieroglyphics, and much of the rich culture of Middle

Eastern civilizations remained unknown until Western scholars relearned those

writing systems in the nineteenth century (using, for example, the famous Rosetta

Stone to translate ancient Egyptian).

Despite their many advantages, the Phoenicians ultimately failed in the competi-

tion of civilizations (see chapter 5). Meanwhile, the Greeks succeeded beyond any-

one’s imagining except, perhaps, their own. The Hellenes had a supreme

confidence in their own superiority. They called all non-Greeks barbarians, a word

derived from what the Greeks thought these foreigners were speaking, namely bab-

bled nonsense. In the Western Mediterranean, the Greeks were often more techno-

logically advanced and sophisticated than natives such as the Celts. The Greeks also

labeled as barbarians peoples like Egyptians or Babylonians, who had brought forth

great civilizations millennia before the Greeks existed and were still wealthy and

mighty compared with the few and scattered Hellenes. Such distinctions were of

no matter to the Greeks. They felt themselves to be the only truly civilized people.

Some Greek attitudes seemed rather strange to their neighbors at the time. For

one, romantic and sexual relationships between men were more common and

accepted in Greece than elsewhere. Many a male teenager was initiated into adult-

hood through a liaison with an older man. These relationships were not like modern

homosexuality and often did not even have a physical sexual dimension. Even Greek

men who were not interested in boys exercised in gymnasia or competed in sports

while wearing no clothing. The athletes in the famous Olympic Games ran, hurled,

boxed, and wrestled in the nude for male spectators (although some young virgin

girls were allowed to attend, partly to check out prospective husband material). Not

only women, but also other non-Greek men were excluded from competing in the

Olympics. Our modern Olympic ideal of bringing together all nations of the world

in sports was not for the Hellenes. Although famous through the ancient world,

PAGE 51.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:40 PS

52

CHAPTER 4

the Olympic Games expressed panhellenism, the idea that all Greeks were similar.

Barbarians were not welcome on the playing field.

While the Greeks shared contempt for non-Greeks, they also separated them-

selves into smaller units. For a while, the Greeks reversed the trend toward empire

so characteristic of the Middle East. Each Greek held allegiance to his own polis

before and above any allegiance to the people as a whole. This political particular-

ism further intensified into the idea of personhood called individualism. The

heroic individual mattered more than the family, more than the city or its people.

The great epic poem, Homer’s Iliad, shows how Achilles and his many virtues,

called are

ˆ

te, were hard to balance against the needs of the larger community. As

the hero sulked in his tent, the Greeks were stalemated in their war against the

Trojans. Because of the pride of Achilles, many died, including his best friend. Was

Achilles to be admired or admonished? In either case, Achilles earned praise for

being the best warrior. In everything, from war to theater, the Greeks competed

with one another. How the Greeks would deal with this feeling of superiority, exclu-

siveness, and individuality became their greatest trial.

Review: How did the Greeks begin as a people and expand through the Mediterranean?

Response:

THE POLITICAL ANIMAL

As the Greeks built their civilization, they entered a period of political experimenta-

tion almost unparalleled in human history. The word polis gives us our word poli-

tics. The Mesopotamian kings and emperors, Egyptian pharaohs, and Persian shahs

lacked politics in our modern, Western sense. Their commands were supposed to

be unquestioned, endorsed by divine mandate. Only a few select elites, the aristo-

crats, had any part in the decision-making process that affected tens of thousands

of subjects. In contrast, the Greeks originated democracy as a form of government.

The Hellenic innovation of true politics broadened the decision making to include

many people, which is what democracy literally means: rule by the people. More

people participated in answering the important question of who pays taxes and

how much. In absolutist monarchies, the kings and aristocrats taxed the peasants

and made war. In a democracy, people taxed themselves and decided in common

PAGE 52.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:41 PS

TRIAL OF THE HELLENES

53

to go to war. Despite the difficulties and failures of the Greeks, their politics have

continued to inspire us to this day.

The first step toward power for the people came in rejecting the most common

political institution of the ancient world: kingship. Instead of allowing their kings

to become gods like most other ancient peoples, the Greeks got rid of most of them.

The Greeks did not, of course, cast off the gods themselves. They still believed

their societies depended upon the favor of deities. At the heart of every city was an

acropolis, ‘‘the high citadel,’’ in which the people built their temples, held their

most important religious ceremonies, and kept their treasures. Yet kings were no

longer needed to play mediator, and neither were priests, at least as a special social

group. When the Greeks got rid of royal dynasties, they also eliminated the ruling

priestly caste. Instead, members of the community shared and alternated in the role

of mediators and officiators in religious ceremonies.

Although the Greeks eliminated the political roles of the royal dynasties and

priestly castes, they found the next step, breaking the power of the wealthy and

well-born families, to be much more difficult. Aristocracy, rule of the better born,

replaced monarchy at first. Remember that a few well-connected families usually

run things. Such happened also in ancient Hellas. The aristocrats supported their

power through their wealth in land, control of commerce, and monopoly of leader-

ship in war. The expensive bronze armor and weaponry of the aristocratic warrior,

such as Achilles had wielded in myth, made the aristocrats dominant on the battle-

field, which in turn secured their monopoly in political counsels.

Politics changed, as it had before and would again, when new military technol-

ogy and tactics created new kinds of warriors in the seventh century

B.C.

The rough

terrain of the southern Balkans was unsuitable for cavalry, and so foot soldiers

became the most important warriors. Then the growing use of iron allowed for new

weapons, as it had for the Assyrians. As trade increased and iron metals became

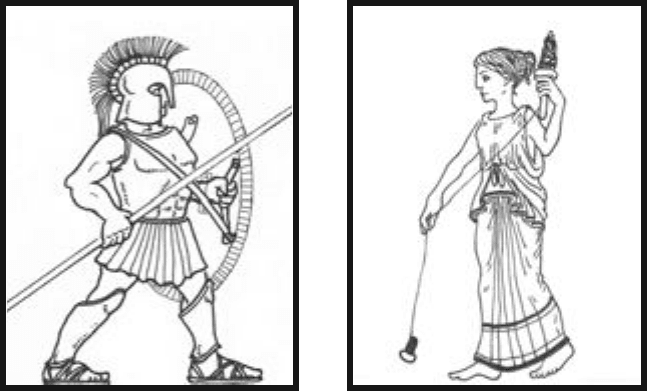

more accessible, a new type of Greek warrior appeared: the hoplite. The hoplite

was lightly protected by a helmet and a large round shield and armed with a long

spear and a short sword.

The key to the hoplite’s success on the battlefield was fighting in coordination

with other hoplites in a phalanx. Each phalanx consisted of about four hundred

men standing in lines eight ranks deep; each man defended himself with his helmet

and large shield that covered both part of him and his neighbor. To attack, soldiers

wielded nine-foot-long spears, as they ran together to smash the enemy. The battle

often turned into a shoving match, each side pushing until the other started to give

way from exhaustion, fear, or the loss of hoplites to wounds. If spears were useless

in close combat, then soldiers swung short chopping swords. At the same time,

they perfected a new warship for the all-important battles at sea: the trireme. While

triremes did have sails, three banks of rowers called thetes provided the essential

means of propulsion. A large ram on the prow would crash into an enemy ship,

aiming to sink it. If that was unsuccessful, armed thetes would board the enemy

and fight hand to hand to seize the ship. Navies organized ships to fight in groups,

like a phalanx at sea.

These two innovations, hoplite and trireme, broke the dominance of the aris-

tocracy in combat and lost them their political monopoly. Repeatedly in history,

PAGE 53.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:41 PS

54

CHAPTER 4

innovations in military methods have forced changes in political structures. In

ancient Greece, a simple peasant could afford the few weapons of a hoplite and

then spend several weeks training to march in formation and kill. Anyone with a

strong back and limbs could be a thete. Once the peasants and merchants realized

that they were putting their lives on the line for their ‘‘country,’’ they demanded a

share of the power and wealth controlled by the aristocrats. Many peasants called

for land reform, taking away some land from those who had inherited a great deal

and giving it to those who had little. Peasants have called for this practice regularly

throughout the history of our civilization. Getting the great landowners to surren-

der power has, however, been more complicated.

The struggle for dominance in Greek city-states reflected the eternal tension

between politics and violence. Ideally, politics should mean that people peacefully

make a decision after civil discussion. The Greek aristocrats personified warriors of

privilege, who believed that their dominance had been granted by the gods. They

resisted any land reform, perceiving it as not in their own best interest. The Greek

peasants, in turn, were equally as determined to gain their version of justice and

fought back. Thus, rebellion and strife have been political tools just as often as laws

and votes. The Greeks labeled a situation when all political discourse had broken

down into riot as anarchy (from the Greek word for a society without the archons,

the appointed administrators). After a struggle, a winning group reasserted the rule

of law and order as the winners interpreted it.

A few members of the aristocracy who sympathized with the plight of the peas-

ants assisted the commoners in the seventh and sixth centuries

B.C.

These leaders

seized power from their fellows and won the favor of the masses by pushing

through reforms. These popular rulers have been given the name of tyrants.To

accuse someone of tyranny now implies ruthless rule for one’s own gain, and

indeed that did happen in Greece. More often, though, the tyrants ruled with harsh-

ness in order to break the power of their fellow aristocrats and grant rights to the

peasants. Greek tyrants were rarely able to establish a dynasty and pass power to

their descendants. Instead, the same people who had helped the tyrants subse-

quently overthrew them, believing, correctly, that they no longer needed the tyrants

once the power of the aristocrats was broken. The mechanisms of political power

had shifted.

After all this bloodshed and suffering, most Greeks settled on some form of

democracy by 500

B.C.

Politically eligible citizens were expected to live up to their

obligations. The ancient Athenians literally called someone who did not serve in

public office or deliberate in civic affairs an ‘‘idiot.’’ The Greek democracy neverthe-

less excluded many people from political decisions, restricting the political rights

of citizenship, the concept that certain members of the polity have defined rights

and responsibilities. First, resident ‘‘foreigners’’ could not participate. A foreigner

was defined as anyone not descended from the founders of the particular polis,

ethnic Greek or not. Second, adult women had no legitimate political role and

would not have in the West until the twentieth century. Third, children were

excluded, as they are today. Fourth, the large numbers of slaves were, of course,

excluded. Fifth, property requirements still kept many of the poor from participa-

tion. Greeks often limited democracy to adult male citizens who held a defined

PAGE 54.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:42 PS

TRIAL OF THE HELLENES

55

amount of wealth, which varied from city to city. So the percentage of people actu-

ally engaged in democracy ranged from 30 percent down to only 3 percent of any

city-state’s population. This percentage was a substantial improvement on the less

than 1 percent of people involved in early Greek or most Middle Eastern civiliza-

tions at the time. It also compares well with modern democracies, where sometimes

only one-third of the population votes in elections.

These restrictions on voting in Greek poleis created the first tension within

democracy and leads to another basic principle:

Democracy is difficult.

Throughout the brief history of Greek democracy, people not only argued but also

killed one another over political principle. Most people cannot easily give up

power. Most people cannot peacefully accept that others with whom they disagree

should have power over them. Most people cannot resist the temptation to enrich

themselves through political office rather than work to improve the community as

a whole. The historical record often shows these sad realities. Sometimes, though,

people have accepted the rules of democracy and created real and just democratic

governments.

A truly functional democracy requires the rule of law and at least two different

ideological positions that can both legitimately disagree and compromise with the

other. Rules have meant that process, not violent power, should guide change. In

ancient Greece, ideology further structured the grounds for debate. The Hellenes

developed two basic political directions that are still with us today. One leaned to

the past and supported individuals with privileges; the other inclined to the future

and wanted to broaden access to status. Factions organized political activity around

either appreciating an imaginary past or favoring the imagined future. In ancient

Greece, believers in the former became the oligarchs. They promoted oligarchy,

which limited rule to the few, namely the old aristocrats and the newly wealthy.

The proponents of the latter were the democrats (which, like the American political

party, are named after the political principle). The ancient Greek democrats favored

expansion of political rights to the widest possible number of adult male citizens.

Not only did the Greeks have these two distinct democratic viewpoints, but they

also had two poleis that exemplified each political ideal: Sparta and Athens.

The city-state of Sparta typified oligarchy. Spartans called themselves Laconians,

which has given us the expression ‘‘speaking laconically’’—using few words to con-

vey great meaning. This city-state was unique among the Greeks because it founded

almost no overseas colonies. Instead, the Spartans conquered their neighboring

Greeks in the Peloponnesus, the handlike peninsula at the southern tip of the Bal-

kans. Most of the conquered Greeks became helots, subjects who held no political

rights and had to surrender half of their agricultural produce annually. The free

citizens of Sparta themselves made up only a small subset, perhaps 3 percent of the

total population, who ruled over all. Since the unfree helots retained their fiercely

independent Greek inclination, the Spartan citizens always feared revolt.

PAGE 55.................

17897$

$CH4 10-08-10 09:26:42 PS