Nof S.Y. Springer Handbook of Automation

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Automation in Hospitals and Healthcare 77.3 Applications 1395

a National Health Information Network (NHIN) to

connect these RHIOs. Unfortunately, even at an insti-

tutional level there are numerous clinical and financial

applications that have difficultly communicating and

thus there are significant unmet needs even within a sin-

gle organization. Many countries across the globe are

issuing tenders to seek solutions for health information

exchange on national levels.

Putting aside the complex business model and or-

ganizational barriers that have been significant barriers

towards significant national and local information ex-

change, there continues to be significant technology

barriers. One of the fundamental challenges resides in

the prime directive of medical informatics in that most

systems store data rather than knowledge and as a re-

sult haveno external references to establish the meaning

of data that needs to be exchanged. For example, con-

sider allergies. Allergies represent one of the most acute

life threatening risks to an individual whenever he en-

counters a healthcare system, especially if he enters the

system unconscious. Surprisingly, there is no common

dictionary for allergies, and as a result most systems

have no method to exchange allergies in a form be-

yond simple free text. With free text allergies there is

no method to perform simple allergy checking before

prescribing or administering a drug.

Today organization such as Health Language 7

(HL7), Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE),

Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel

(HITSP), and the Center for Healthcare Information

Technology are all working on establishing standards to

facilitate interoperability across institutions and across

vendors. Although there are emerging standards for

rudimentary exchange of information today there are

surprisingly few examples of information exchange

even at the level we have come to expect in the banking

industry. With patients continually changing healthcare

environments due to changes in health and changes

in insurance, the challenge of interoperability must be

solved to ensure that information technology has a sig-

nificant impact on the quality of care.

77.3.7 Enterprise Systems

Historically, patient access and financial systems were

the first to gain a foothold in healthcare. Driven by the

bottom line, these supported the back office and had no

access to (or need for) clinical data. Clinical systems

followed, designed to address specific needs in individ-

ual care areas such as labor and delivery, where there

was a need to record and store the massive amounts

of information generated by fetal heart monitors and

other devices. For the past two decades, lab systems

built around the workflow of technicians and pathol-

ogists have had the capability to collect results from

a wide array of tests and presentphysicians with a single

view of all the data for each patient (although in most

physician’s offices that information is still presented on

paper rather than electronically).

Because these systems were developed for specific

care areas, each tightly adhered to the workflow in one

particular area. Many healthcare organizations adhered

to a best-of-breed approach, buying a lab system from

one vendor, a pharmacy system from another, a peri-

operative system from a third, and so on. These care

area-specific systems can be more nimble, and can be

installed in a matter of weeks, but require complex in-

terfaces in order to share data with each other. As time

passed, clinicians recognized the need for enterprise-

wide systems, so some vendors of area-specific systems

began broadening their scope.

Other vendors took the approach of developing

enterprise-wide systems that allow information to eas-

ily cross the boundaries between care areas. Consider,

for example, what happens when a physician orders

medication for a hospital patient: the provider needs

to know whether the patient is allergic to that drug, or

has been given any other medication that should not

be combined with the new one, formularies must be

consulted to see whether the hospital is dispensing the

drug and whether the patient’s insurer will pay for it,

the order must be transmitted to the hospital pharmacy,

where the pharmacist double-checks the dose to make

sure it is appropriate for the patient’s age, weight, and

condition. After the pharmacist dispenses the drug, it

must be conveyed to the right location in the hospital,

where a nurse will pick it up, administer it to the pa-

tient, and document the time of administration (perhaps

using a barcode scanner to make sure the right patient is

being given the right medication).

The trade-off for the easy flow of information across

the enterprise is in specificity and implementation time.

The best area-specific systems do one thing only, and

do it better than the current generation of enterprise sys-

tems. Smaller, more discrete systems are also easier and

faster to install. As the technology matures, however,

we will see a convergence as enterprise systems acquire

the greater depth of area-specific capabilities.

Part H 77.3

1396 Part H Automation in Medical and Healthcare Systems

77.4 Conclusion

The practice of healthcare is incredibly complex gen-

erates massive amounts of mission critical data that

must be assimilated and acted upon quickly. In many

cases, the margins for error are slim and the costs

of error immense. Information technology has the po-

tential to transform the way we practice medicine by

turning data into knowledge and knowledge into ac-

tion. This will enable providers to deliver better quality

care at lower cost, to maintain consistency of care for

a given disease while appropriately tailoring care to

each individual patient’s unique condition and genetic

makeup, and to localize the application of care guide-

lines based on knowledge about specific populations of

patients.

Some of the tools to accomplish these goals exist

today, but they need to be modified or adapted to suit

the uniquedemands of healthcare.We have systems that

can alert clinicians to potential errors, for example, but

these systems must be fine-tuned to prevent alert fa-

tigue. Other challenges, such as interoperability, which

enables data sharing among systems from different ven-

dors, remain largely unanswered at the moment.

References

77.1 L.T. Kohn, J.M. Corrigan, M.S. Donaldson (Eds.):

To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System

(National Academy Press, Washington 1999)

77.2 J.E. Wennberg: Unwarranted variations in health-

care delivery: implications for academic medical

centers, Br. Med. J. 325, 961–964 (2002)

77.3 E.A. McGlynn, S.M. Asch, J. Adams, J. Keesey,

J. Hicks, A. DeCristofaro, E.A. Kerr: The quality of

health care delivered to adults in the United States,

New Engl. J. Med. 348(26), 2635–2645 (2003)

77.4 R. Mangione-Smith, A.H. DeCristofaro, C.M. Setodji,

J. Keesey, D.J. Klein, J.L. Adams, M.A. Schuster,

E.A. McGlynn: The quality of ambulatory care de-

livered to children in the United States, New Engl.

J. Med. 15, 1515–1523 (2007)

77.5 C. Clancy, K. Cronin: Evidence-based decision mak-

ing: global evidence, local decisions, Health Aff.

24(1), 151–162 (2005)

77.6 R. Hillestad, J. Bigelow, A. Bower, F. Girosi, R. Meili,

R. Scoville, R. Taylor: Can electronic medical record

systems transform health care? Potential health

benefits, savings, and costs, Health Aff. 24(5), 1103–

1117 (2005)

77.7 Clinical Content: http://www.clinicalcontent.com/

about (last accessed May 20, 2009)

77.8 M.A. Shipp, K.N. Ross, P. Tamayo, A.P. Weng,

J.L. Kutok, R.C. Aguiar, M. Gaasenbeek, M. An-

gelo, M. Reich, G.S. Pinkus, T.S. Ray, M.A. Koval,

K.W. Last, A. Norton, T.A. Lister, J. Mesirov,

D.S. Neuberg, E.S. Lander, J.C. Aster, T.R. Golub:

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcome predic-

tion by gene expression profiling and supervised

machine learning, Nat. Med. 8(7), 68 (2002)

77.9 S. Adak, K. Illouz, W. Gorman, R. Tandon, E.A. Zim-

merman, R. Guariglia, M.M. Moore, J.A. Kaye:

Predicting the rate of cognitive decline in aging

and early Alzheimer disease, Neurology 63(1), 108–

14 (2004)

77.10 H.B.Nguyen,J.Banta,T.Cho,C.VanGinkel,

K. Burroughs, W.A. Wittlake, S.W. Corbett: Mor-

tality predictions using current physiologic scoring

systems in patients meeting criteria for early

goal-directed therapy and the severe sepsis re-

suscitation bundle, Shock 30(1), 23–28 (2008)

77.11 C.M. Birkmeyer, D.E. Wennberg: Patient Safety

Standards (Leapfrog Group, 2003)

Part H 77

1397

Medical Auto

78. Medical Automation and Robotics

Alon Wolf, Moshe Shoham

Robotic systems that are integrated in medical

applications are designed to help and assist rather

than injure a human being, whether it is the

patient or the operator. This chapter presents

the classification of medical robots as passive,

semiactive, active, remote manipulators, and

navigators. The kinematic structure of medical

robots is discussed next, as are the fundamental

requirements from medical robots. Finally, the

main advantages and emerging trends in medical

robotics are given.

78.1 Classification of Medical Robotics Systems1398

78.1.1 Passive Medical Robotic Systems ....1398

78.1.2 Semiactive Medical

Robotic Systems ...........................1399

78.1.3 Active Medical Robotic Systems ......1399

78.1.4 Remote Manipulators ...................1400

78.1.5 Navigators...................................1401

78.2 Kinematic Structure

of Medical Robots.................................1403

78.3 Fundamental Requirements

from a Medical Robot............................1404

78.4 Main Advantages

of Medical Robotic Systems....................1404

78.5 Emerging Trends

in Medical Robotics Systems ..................1405

References ..................................................1406

1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through

inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey orders given to it by human

beings except where such orders would conflict with

the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as

such protection does not conflict with the First or

Second Law.

Written almost 65years ago, these three laws of

robotics by the famous science fiction author Issac

Asimov (Runaround, 1942) are still very relevant and

serve, though not literally, as guidelines for the field of

medical automation and robotics. By definition, robotic

systems that are integrated in medical applications are

designed to help and assist rather than injure a human

being, whether it is the patient or the operator. Many

precautions (more than one would find in nonmedical

robotic systems) are being taken to ensure the safety

of patients and operators. As presented in this chap-

ter, these safety measures include, among others, dual

backup systems, as a minimum, and fail-safe systems.

These redundant systems are there to prevent unwanted

motions that may harm the patient or the staff, to assure

accurate performance of the task, and also to protect the

robot itself as stated in the third law of robotics.

As elaborated in this chapter, current medical

robotic systems aredividedinto three categories, mainly

reflecting level of autonomy. The most popular and

widely implemented method is teleoperation, where the

robotic system follows the operator’s (surgeon’s) hand

motions from an offsite control console that can be lo-

cated either in the operating room or even somewhere

overseas using fast communication lines. In this mode

of operation,the robot,just like inAsimov’s second law,

obeys and follows the operator’s commands and mo-

tions. These systems are capable of filtering tremors in

the surgeon’s hand movements (crucial in neurosurgery

and ophthalmic surgery), scaling down the operator’s

motions and forces, and at the same time preventing un-

wanted motions that could harm the patient (the active

constraint concept).

The first swallows of medical robots appeared in

the mid 1980s and early 1990s with the implemen-

Part H 78

1398 Part H Automation in Medical and Healthcare Systems

tation of the Puma 560 for stereotactic neurosurgery.

The application was a computed tomography (CT)-

guided needle steering system for brain biopsy. Then

came ROBODOC from Integrated Surgical Systems

in 1992. ROBODOC milled out precise fittings in the

femur for hip replacement surgery. ROBODOC was

a pioneering surgical active robot that paved the way

for other robotic systems, mainly remotely manipu-

lated, semiactive, and active constraint robots. Current

surgical applications are in the fields of gastroin-

testinal surgery, urology, gynecology, cardiothoracic

surgery, oncology, orthopedic surgery, and neurosur-

gery.

Despite more than two decades of research in the

field of medical robots, it seems that this field has not

yet reached maturity and is still in its infancy. Neverthe-

less this fact does not prevent researchers from thinking

of the next step, i.e., integration of computer-assisted

surgery (CAS) devices into one complete system. This

is called the operating room of the future (ORF). This

initiative is crucial in light of the increasingly growing

number of surgical instruments, monitoring and imag-

ing devices, information systems, and communication

networks used in modern operating rooms and inter-

ventional suites. See also Chap.82 on Computer- and

Robot-Assisted Medical Interventions.

78.1 Classification of Medical Robotics Systems

Medical robots have been classified in the literature

according to the following categories: remote manip-

ulators, and passive, semiactive, and active robots, by

Cinquin [78.1], Stulberg [78.2], Taylor [78.3,4], Troc-

caz [78.5], Bainville [78.6], and Nolte [78.7].

Since this area of research is very dynamic and, in

our opinion,has notyet reached maturity, it is likely that

categories and classifications that are widespread today

will change over time, with the evolution of new con-

cepts. Nevertheless, we present in this chapter a brief

overview of current leading technologies and trends in

the field of medical robotics. For an extensive review

of the literature and classification of existing medical

robotic system we refer readers to [78.8–10].

Finally, we also present the major considerations

to be taken into account in the design of new medical

robotic systems.

78.1.1 Passive Medical Robotic Systems

Passive medical robotic systems support the surgical

procedure, but take no active part during surgery. In

other words, the surgeon is in full control of the sur-

gical procedure at all times, i.e., the actual surgical

procedure is conducted by the surgeon. Early versions

of Arthrobot [78.11] fall into this category of passive

systems. In early stages, the robot was used as an as-

sistant in the operating room to hold the patient’s limb

during joint replacements of knees and hips. Arthrobot

had no sensing capabilities and was able to move only

under explicit human control. Today, one of the main

forms of passive medical robotics is active constraint

robotic systems. Acrobot [78.12] is an example of an

active constraint passive robotic system. Developed by

Davies et al. [78.13–15], its core proprietary technology

centers on thedevelopment of anewtype ofrobotic con-

trol: active constraint robotics for orthopedic surgery.

This concept facilitates synergy between the surgeon

and the robot, provides active assistance to the surgeon,

and prevents surgical errors. The surgeon guides the

surgical tool that is attached to the robot with a han-

dle with a force sensor attached to the robot tip, and

thus uses his/hersuperior humansenses and understand-

ing of the overall situation to perform the surgery. The

robot provides precise geometricaccuracy and increases

the safety by means of a predefined three-dimensional

(3-D) motion constraint that prevents cutting outside

a predefined safe region. This approach, known as

hands-on robotics, keeps the surgeon in the control loop

throughout the surgery. Moreover, the robot is guided

by preoperative image-based planning software. This

image-based software uses a patient’s CT data to facil-

itate precise planning of the surgery, allowing implant

selection and optimal positioning within the joint.

Another passive robot utilizing the active constraint

concept is the MAKO robot, a haptic robotic sys-

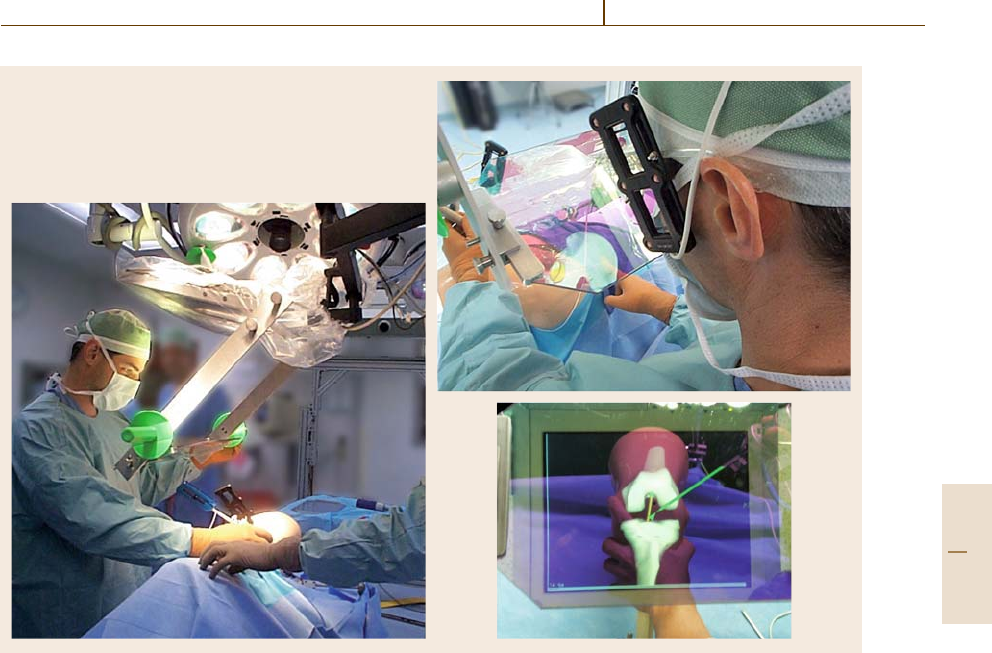

Fig. 78.1 Freehand sculptor by BlueBelt

Part H 78.1

Medical Automation and Robotics 78.1 Classification of Medical Robotics Systems 1399

tem that adds the sense of touch to a robotic-assisted

surgical platform. The MAKO Haptic Guidance Sys-

tem is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared,

surgeon-interactive robotic system that enables the or-

thopedic surgeon to plan the alignment and placement

of knee resurfacing implants preoperatively and make

intraoperative bone-conserving cuts accurately within

the safe workspace limited by the robot.

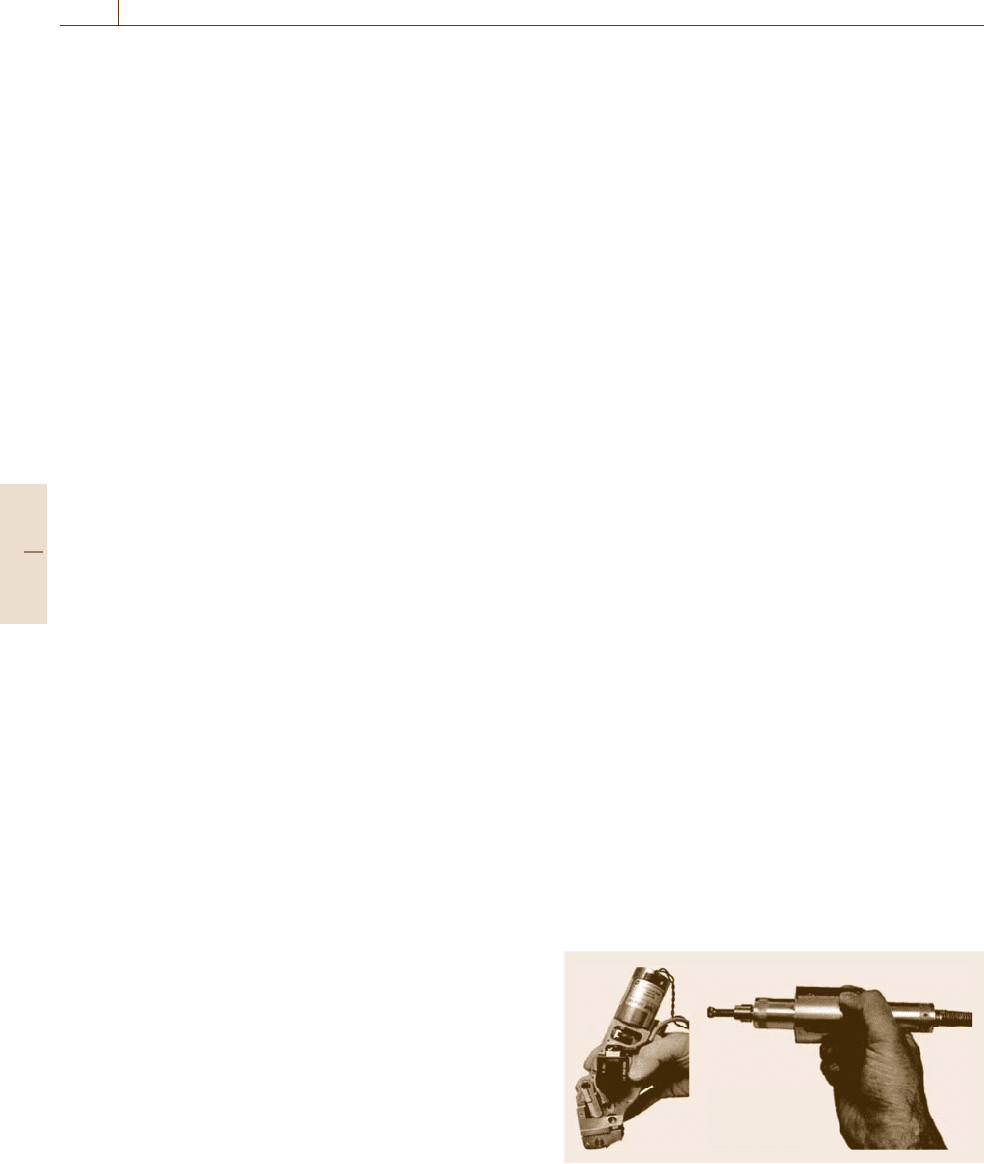

The precision freehand sculptor (PFS) by BlueBelt

is a handheld tool to assist the surgeon in accurately

cutting these shapes (Fig.78.1). Its rotating cutter only

allows the surgeon to remove waste bone; the cutter in

turn retracts when it hits good bone (i.e., bone that is

not supposed to bemachined). Thus the surgeon can use

the PFS freehand while it automatically restricts the cut

to the proper shape [78.16]. This mode of operation is

a modification of the active constraint concept. Instead

of preventing hand motion, the system automatically

and actively prevents cutting.

78.1.2 Semiactive Medical Robotic Systems

The semiactive category is presented in [78.17]. In this

research a robot acts as an assistant during the oper-

ation by holding a tool in a steady position to allow

accurate guidance of surgical tools. Other more up-to-

date examples of semiactive systems are the NeuroMate

(Integrated Surgical Systems, USA) and PathFinder

(Armstrong HealthCare Ltd., UK). They provide guid-

ance ofthe surgical tool but theactual surgical operation

is conducted by the surgeon.

One of the very first applications of robotic sys-

tems in a surgical theater was positioning of a needle

for stereotactic neurosurgery [78.18]. This application

involves placement of a needle in a very accurate man-

Fig. 78.2 Mazor’s SpineAssist miniature robot for spine

surgery

Fig. 78.3 SpineAssist during surgery

ner in a predefined location in a percutaneous approach

(later used as a semiactive system). Further develop-

ment of this approach is described in [78.19].

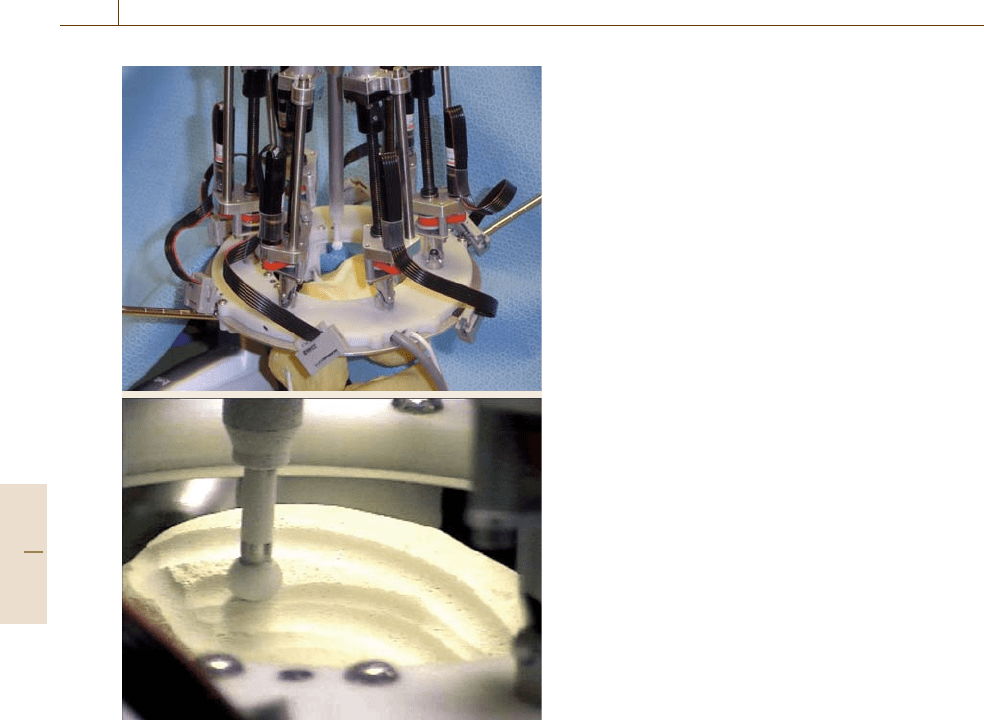

A different concept of a semiactive robot had been

developed at the Robotics Laboratory at the Technion–

Israel Institute of Technology and is manufactured and

marketed by Mazor Surgical Technologies [78.20]. Ma-

zor’s SpineAssist (Figs. 78.2 and 78.3)isa2×4inch,

250g, image-based robot designed to guide the surgeon

to precise locations along the patient’s spine according

to a preoperative plan. Its small size and light weight al-

lows mounting the robot directly on the patient’s back,

thus overcoming the patient’s motion relative to the

robot base and as a result improving the accuracy of

the operation. The FDA- and Council Europe (CE)-

approved SpineAssist robot has performed hundreds of

cases and implanted thousands of screws with better

clinical outcome than the freehand approach while at

the same time allowing a minimally invasive approach.

PiGalileo is another bone-mounted guiding system.

Just like in the case of SpineAssist, the actual surgical

operations done with PiGalileo are still performed by

a surgeon, with the electromechanical positioning de-

vice aiding the surgeon in instrument positioning. This

technology is completely under the surgeon’s control

at all times, providing valuable intraoperative feed-

back to the surgeon to help improve precision, thereby

potentially leading to better implant alignment and po-

sitioning.

78.1.3 Active Medical Robotic Systems

Active robotic systems perform surgical tasks, such as

drilling or milling, autonomously with no direct inter-

vention of the surgeon [78.21–23]. This group includes

Part H 78.1

1400 Part H Automation in Medical and Healthcare Systems

Fig. 78.4 MBARS used for joint arthroplasty

active robots such as RoboDoc,CASPAR, and MBARS.

Perhaps one of the most famous active robots today is

RoboDoc (Integrated Surgical Systems), developed by

Paul et al. [78.24,25]. The system was originally used

for total hip replacement procedures, yet was later mod-

ified foruse in total knee replacement procedures(today

it is less used because of controversy over long-term

clinical effectiveness).

MBARS (Fig.78.4) is an active version of the bone-

mounted robotic system concept. Although this is still

an academic study, the system demonstrates the capa-

bility to actively prepare the bone cavity for an implant

during joint arthroplasty procedures.

The robot is composed of six linear actuators that

are connected in parallel between two rigid platforms:

the lower reference platform and the upper platform,

which is the moving end-effector of the robot. This

structure is known as the classical Stewart–Gough six-

degree-of-freedom robot. The robot is attached to the

femur by three pins: one pin is inserted into the medial

epicondyle, one into the lateral epicondyle, and one into

the metadiaphyseal region of the femur. A rigid con-

nection of the robot to the operated bone is obtained

through these three pins. The robot is equipped with

a milling device, which actively mills the bone accord-

ing to the preoperative plan.

The CyberKnife robotic radiosurgery by Accuracy

System is a radiosurgery system designed to treat tu-

mors anywhere in the body with high accuracy. Using

image-guidance technology and computer-controlled

robotics, the CyberKnife system is designed to track

the tumor continuously, detect its location, and correct

for tumor and patient movement in real time throughout

the treatment. Because of its extreme precision, the Cy-

berKnife system does not require invasive head or body

frames to stabilize patient movement, vastly increasing

the system’s flexibility.

Gamma Knife PERFEXION is Elekta’s new Lek-

sell system for stereotactic radiosurgery in the brain,

cervical spine, and head and neck regions. The Leksell

Gamma Knife PERFEXION expands treatment reach,

offering a wider range of treatable anatomical struc-

ture. This expanded anatomical treatment area offers

dramatic new opportunities to increase patient volume.

Leksell Gamma Knife PERFEXION makes the entire

procedure more efficient and user-friendly. Collimator

changes can be made by the control program, optimiz-

ing the workflow and significantly reducing treatment

time.

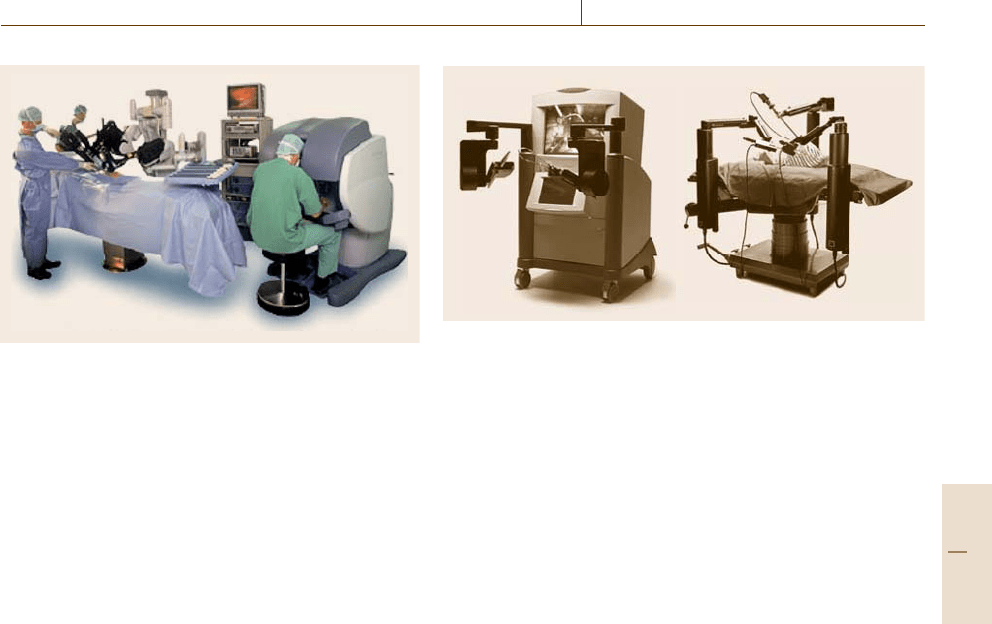

78.1.4 Remote Manipulators

Perhaps the most commonly used medical robots to-

day are remote manipulators. Remote manipulators are

robotic system that can be operated from a remote loca-

tion. In other words, the surgeon does not have to be at

the bedside, nor even in the operating room, and yet can

still perform the surgical procedure using the robotic

system, which serves as his hands and eyes.

Remote manipulators are robotic systems that can

be operated from a remote location. Medical proce-

dures utilizing this mode of operation are often named

telesurgery. The first concept was developed at Stanford

Research Center as a project for the USArmy. The con-

cept of telesurgerywas firstdemonstrated in2001, when

an expert surgeon removed the gallbladder of a 68-year-

old patient. This looks like a very common procedure

that is done on a daily basis in many locations around

the world, with one exception: the patient was oper-

ated on in Strasbourg, France and the surgeon operated

Part H 78.1

Medical Automation and Robotics 78.1 Classification of Medical Robotics Systems 1401

Fig. 78.5 Da Vinci system

from New York. For successful performance of such

a telesurgery, a high-speed computer connected through

a reliable high-speed network is required. This success-

ful demonstration has opened new horizons of surgical

procedures performed worldwide with experts sitting in

communication centers. Telesurgery can bring experts

to places where there are scarce medical facilities and

medical professionals, suchas third-world countriesand

war zones.

Although the first telesurgery was carried out only

in 2001, telesurgical systems were introduced earlier.

Computer Motion (now Intuitive Surgical Inc., USA)

introduced in 1994 the AESOP system. This robotic

system was used to manipulate a camera during laparo-

scopic surgery. Overall, about 70 000 surgeries were

performed worldwide using this system. Once acquired

by Intuitive, the AESOP system was not sold anymore.

Instead, Intuitive Surgical Inc. introduced the Da Vinci

medical robot. During surgery, the surgeon operates the

robot from a remote console using a specially design

control mechanism and a stereo vision system. In April

2005, the Da Vinci system (Fig. 78.5) was approved by

the FDA toperform gynecological procedures, although

it is used for other procedures as well, such as urologic,

general laparoscopic,noncardiovascular, thoracoscopic,

and others.

Although Intuitive Surgical is a world leader in the

development of robotic technology of minimally inva-

sive surgery (MIS) with its Da Vinci robot, it is worth

mentioning another medical robot that competes with

the Da Vinci system for the same market. Computer

Motion (now owned by Intuitive Surgical) introduced

the Zeus system (Fig.78.6). Just like the Da Vinci sys-

tem, Zeus is composed of multiple robotic arms capable

of manipulating MIS tools and visualization equipment

for cardiac surgery.

a) b)

Fig. 78.6a,b Zeus system: (a) console, and (b) robot arms

On 5 April 2001 a 63-year-old male patient un-

derwent multivessel off-pump coronary artery bypass

surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

(UPMC) Presbyterian Hospital using the Zeus system.

This was the first time ever that such a procedure was

carried out. MarcoA. Zenati from the UPMC Depart-

ment of Surgery operated the robot while seated at

a console about 10 feet from the patient. The robot was

equipped with an endoscope, whichwas manipulated by

one of the robotic arms using voice commands, while at

the same time the other two arms were controlled by

operating handles that resemble conventional surgical

instruments.

78.1.5 Navigators

Surgical navigators are the central element in many

medical robotic system [78.26]. They come into play

during the registration procedure. Registration is a cru-

cial and necessary procedure, during which each part

of the medical system is synchronized. Most medi-

cal robotic systems include preoperative (sometimes

intraoperative) planning of the medical procedure. Dur-

ing this step, a virtual surgery can be performed

and simulated on a computer screen (just like with

any computer-aided design system). The data pro-

videdtothesurgeonispatientspecificandisusually

based on a preoperative CT or magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) scan. The end result of this proce-

dure is the transformation that maps the anatomical

position in the operating room to its preoperative

CT/MRI-based model. One example of a method for

achieving this transformation is minimization of the

pointwise distance between a cluster of anatomical

points collected intraoperatively and points on the

preoperative surface model. The coordinates of anatom-

ical points are acquired by touching points on the

Part H 78.1

1402 Part H Automation in Medical and Healthcare Systems

patient’s anatomy (anatomical landmarks) using an

optically tracked probe [78.27]. It is sometimes eas-

ier to think of these systems as global positioning

systems (GPSs) for the operating room. The basic

concept of a surgical navigation system is to ascer-

tain the position, i. e., the location and orientation, of

the relevant components of the system and the pa-

tient’s anatomy in a global coordinate system such

that their relative position can be determined. Dur-

ing surgery, the position coordinates provide precise

guidance to the surgeon to perform a preplanned pro-

cedure.

In 1974, Schlondorff et al. [78.28] developed one

of the first systems for navigational calculations involv-

ing bone. The system used a radiographic centimeter

scale held between the patient’s teeth during a lateral

roentgenogram. The measurements enabled the calcula-

tion of the distances between several anatomical points.

Later, Watanabe et al. [78.29] from Siemens Corpo-

ration published their work on the first model of the

Neuronavigator, a mechanical device based on a multi-

joint 3-D digitizer. The device is used to track the tip of

the sensor arm by indicating its location on preoperative

CT or MRI images.

One of the first systems to use an optical-based

navigation technique was HipNav (Fig. 78.7), devel-

oped at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, PA

(USA) by DiGioia and Jaramaz [78.30]. The sys-

tem was the first computer-assisted navigation system

for cup placement in total hip replacement (THR)

surgery. Beside its significant clinical contribution, this

has set the standard for preoperative planning and

range-of-motion (ROM) simulations for THR.HipNav

incorporated informationprovided toit by the OptoTrak

system by Northern Digital Inc., Waterloo, Ontario.

The OptoTrak system is composed of three charge-

coupled device (CCD) cameras contained in a rigid

enclosure and a set of active trackers, where the body

of each tracker incorporates a set of light-emitting

diodes (LEDs) mounted at precise relative positions,

and the position of each tracker can be resolved in

the OptoTrak coordinate system. For the HipNav sys-

tem, the trackers were fixed to tools, implants, and

the patient’s bones, enabling active tracking of their

positions during operative procedures. Since HipNav,

there have been other systems that employ this type

of technology, including the VectorVision, SurgiGATE,

Navitrack, StealthStation, Stryker, and Surgetic sys-

tems.

A new version of medical navigators is the image

overlay concept (Fig.78.8). Image overlay is a com-

HipNav system in DiGioia’s

operating room

Fig. 78.7 HipNav system

puter display technique that superimposes computer

images over the viewer’s direct view of the real

world [78.31]. In other words, it is a form of augmented

reality in that it merges computer-generated informa-

tion with real-world images by the projection of virtual

objects in real scene. To do this the system needs to

project the virtual image onto some sort of screen. The

most common measure used is a semitransparent dis-

play device (like a heads-up display in fighter planes),

which allows both viewing the real objects while at the

same time overlaying the virtual image on them. For

example, a 3-D image of a bone, reconstructed from CT

data, can be displayed to a surgeon inside the patient’s

anatomy at the exact location of the real bone, regard-

less of the position of either the surgeon or the patient

(Fig.78.8), creating an elusion of an image which ap-

pears to the viewer to be inside the real objects. To do

this in a convincing yet accurate way, the positions of

the viewer’s head, objects in the environment, and com-

ponents of the display system are all tracked in space.

These positions are used to transform the images so

that they appear to be an integral part of the real-world

environment.

Part H 78.1

Medical Automation and Robotics 78.2 Kinematic Structure of Medical Robots 1403

Fig. 78.8 Image overlay

This technology has many clinical applications; one

of the most common is needle steering, i.e., manipulat-

ing a real/virtual needle into remote unexposed organs

for biopsy, drug delivery, and interventions.

78.2 Kinematic Structure of Medical Robots

In most up-to-date medical robotic systems, a serial

robot is used as a surgical assistant. These robots

suffer from numerous drawbacks related to the se-

rial manipulator, such as low rigidity and accuracy.

The fact that theses robots are integrated in medical

procedures, where accuracy and safety is a matter of

life and death, has led researchers to look for bet-

ter manipulators suited for a specific surgical task or

field of tasks. A family of robots found suitable for

medical application is parallel robotic mechanisms.

Grace and Brandt [78.32, 33] stressed the advantages

of parallel manipulators compared with serial manip-

ulators in surgical operations, mainly due to their low

weight, compact structure, better accuracy, stiffness,

restricted workspace, and low price. However, paral-

lel manipulators have some drawbacks. One of the

main disadvantages of parallel robots is their lim-

ited workspace. Nevertheless, limited workspace can

be considered as an advantage in medical applications

where therequired workspaceis itselfvery limited. This

attribute limits the potential placement positions of the

robot in the operating room (OR), since the parallel

robot has to be positioned very close to the operating

area in order to be able to perform a surgical task within

its limited workspace. In most cases, this requirement is

not feasible due to physical conditions in the OR.One

of the tested solutions has been designed with the en-

tire robotics system attached to the OR ceiling so that

the robot works upside down, as proposed for example

in Fig. 78.5. Inthis way,the robotdoes notinterfere with

the surgical procedure, and is activated and maneuvered

to the operating area when required.

Part H 78.2

1404 Part H Automation in Medical and Healthcare Systems

78.3 Fundamental Requirements from a Medical Robot

The fundamental requirements from a medical robot

for surgery tasks were introduced in [78.35], where the

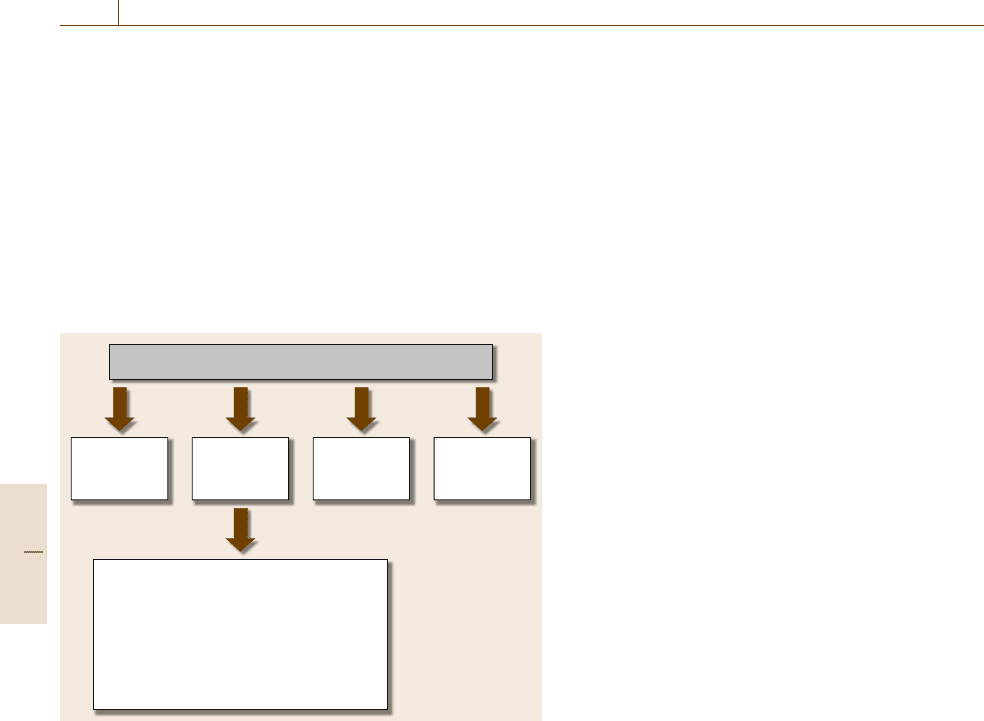

authors stressed the safety requirements (Fig.78.9):

1. Effective control. Both force and speed control of

the end-effector should be allowed or limited by

hardware in all robot configurations.

2. Workspace. The robot workspace has to be limited

to the effective area of the operation, to prevent ac-

Fundamental requirements from a medical robot

Simple

operation

Safety

Easy

sterilization

Compact

size and

low weight

1. Effective control

2. Limited workspace

3. Immunity against magnetic interference

4. Fail-safe mode

5. Safe behavior near singularities

6. Limit force and force feedback

7. Full control option

Fig. 78.9 The fundamental requirements from a medical robot

[78.34]

cidental damage both to the physician and to the

patient.

3. Limited forces or force feedback. The force applied

by the robot during procedures where the robot

takes active tasks and is in contact with live tissue

must be fully controlled. Moreover, in procedures

where different levels of force are applied (such as

bone cutting [78.36]), the physician needs as much

data as possible from the robot concerning the force

applied.

4. Full control option. In procedures where the robot

automatically performs a surgical procedure, the

physician has to be able to take over control of the

robot at any stage during the operation.

5. Fail-safe features. In the event of a malfunction

in the robot, the system has to switch to a fail-

safe mode; for instance, in case of a power failure,

the robot has to remain in its current location until

power is restored.

6. Singularity behavior. The robot path planning must

avoid passing near singular configurations, or ac-

tively prevent the surgeon from driving the robot

through singular configurations, if any, or de-

signed in such a way that all singular poses of

the robot are outside the operating work enve-

lope.

7. Sterilizability. The robot structure must allow steril-

ization, or be protected with a suitable cover.

8. Immunity against magnetic interference of other

surgical tools available in the OR.

78.4 Main Advantages of Medical Robotic Systems

Several researchers have investigated the advantages of

robotic systems in surgery. Kazanzides et al. [78.37]

compared the cross-section of manually broached im-

plant cavities to cavities milled by robots in hip

replacement surgery. The results of this research have

illustrated the robot’s precision compared with the pre-

cision of the human hand. Kavoussi et al. [78.38]

compared the performance of a human to that of a robot

assistant in manipulating the laparoscope. The results

of this research emphasize the superiority of the robot

compared with the human hand in terms of steadiness.

Cameron and Pradeep [78.39] measured the accuracy

of the human hand of four skilled eye surgeons. The re-

sults stressed the tremor and inaccuracy of the human

hand, even for skilled surgeons. An average root-mean-

square (RMS) error of 49μm was obtained when asked

to hold an instrument steady, and 133μm for repeated

actuation. Cameron et al. [78.40] presented a robotic

prototype that incorporates sensing and actuation, re-

porting accuracy of 5μm and better for a robotic system

holding an ophthalmologic microsurgical instrument,

representing a significant improvement with respect to

those presented in the first article [78.39]. These results

indicate that the combination of advanced medicine

with high-technology research capabilities can improve

many surgical procedures that are currently performed

manually and are limited by restricted accessibility and

the lack of preciseness of the human hand. Areas which

Part H 78.4