Nof S.Y. Springer Handbook of Automation

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Automation in Hospitals and Healthcare 77.2 The Role of Medical Informatics 1385

ical ontologies are needed to explicitly articulate the

relationships.

The second example is rule writing for decision

support or reporting. While electronic medical records

systems have allowed institutions to write rules for de-

cision support utilization of rules has been low. In part,

this is due to the difficulty of writing rules without an

ontology. Consider writing a rule that would generate

a list of all patients with lung disease who are also on

blood pressure medication. With ontology this is a sim-

ple task; without one, it requires compiling exhaustive

lists of all possible lung diseases and all possible blood

pressure medications, and then mapping this back to

specific field names in the medical record. These lists

would have to be maintained as new drugs come on the

market or new conditions identified.

77.2.4 Knowledge Generation

Knowledge generation uses information technology to

augment pulling information from the clinicians’ under-

standing of the medical literature. The daily activities of

patient care generate new information about individual

patients and entire populations, but the sheer quantity of

data is overwhelming. Once data has been digitized, IT

systems can synthesize even massive amounts of infor-

mation into usable insight through two key routes: data

analysis and visualization.

Other industries rely on data analysis and data min-

ing as a significant source of insight. In healthcare,

where an operating margin of 2–4% is considered ex-

ceptional, many institutions have implemented some

level of financial data analysis. With respect to clinical

data, however, the lack of digitized information has hin-

dered the use of data analysis to generate insight about

clinical practices outside the academic research setting.

Data analysis can enable clinicians to make in-

quiries about the efficacy of daily practice in the same

waythat knowledge canbe derivedfrom controlled clin-

ical trials. A review of data at the population level can

reveal patterns that are not observed in isolation. In this

way the process of managing patients leads to greater

insight about the best way to manage those patients

going forward.

For example, it is widely recognized that induc-

ing labor before the 39th week of pregnancy can have

deleterious effects that compromise the health of the

newborn, yet early inductions still occur with relatively

high frequency. In a one-on-one interaction between pa-

tient and physician, it is easy to find reasons to induce

this patient’s labor early: late stages of pregnancy are

increasingly uncomfortable for the woman, the doctor

will be out of town, or other calendar issues come into

play. With each individualdecision, neitherprovider nor

patient is looking at the bigger picture.

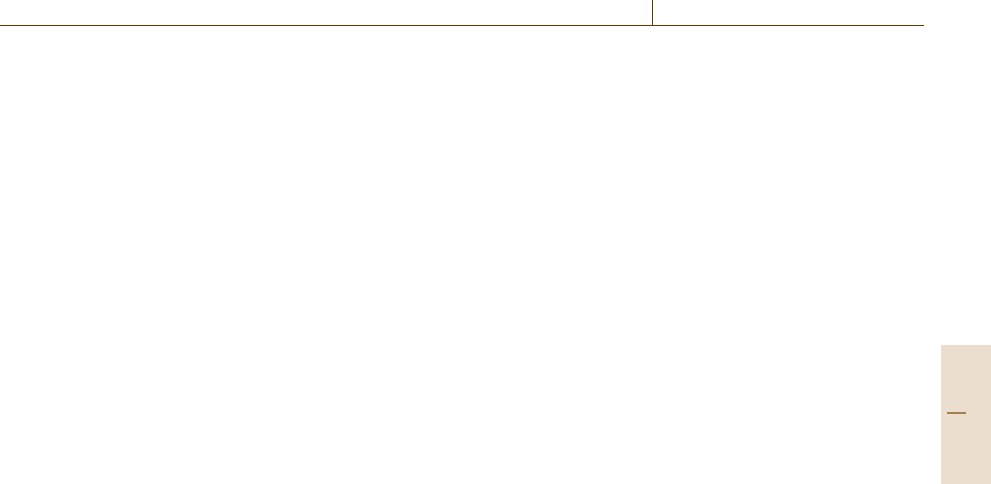

At Intermountain Healthcare, an integrated delivery

network headquartered in Salt Lake City, data analysis

of almost 40000 delivers deliveries in 2000–2001 re-

vealed an increased rate of neonatal intensive care unit

(NICU) admission for babies induced before week 39

(Fig.77.5). The research revealed a one to two weeks

delay could have avoided as many as 220 NICU ad-

missions. Once this data was available, the institution

developed and implemented an evidence-based triage

protocol that set a higher threshold for elective induc-

tions. The rate of early elective inductions dropped

to 5%, significantly reducing unnecessary NICU ad-

missions. Thus, the generation of knowledge through

population data analysis also led to insight that moti-

vated providers to change their practice.

Looking for trends also enables institutions to

improve management of patient care. Ideally, these

insights will extend beyond clinical knowledge to en-

compass the process of care. Electronic medical records

enable institutions to capture information about cost,

clinical data resource utilization, and process times. Us-

ing this information, they can begin to understand the

consequences of practice patterns and resource alloca-

tions, and assess the value of the care they deliver. As

institutions often focus on cutting costs without know-

ing the impact on quality, the analysis can demonstrate

ways to provide the right kind of care while actually

driving down per capita cost. Many examples exist

where institutions deliver the highest quality of care

with the lowest per capita rates, as consists of com-

plicated processes, resource allocations and practice

patterns with multi-fauceted practice patterns attribute.

This analysis will become essential as more third-party

payers adopt pay-for-performance programs that base

reimbursement on quality rather than quantity of care.

With paper records, physicians write summaries that

effectively filter out much of the granular information

about a patient’s condition. Other information may be

stored in archives, or simply filed in some other part of

the healthcare organization where they cannot be im-

mediately accessed. One of the paradoxes of digitizing

information is that the amount of accessible informa-

tion quickly becomes so overwhelming that clinicians

can no longer sift through all of it to find the relevant

information they need.

Data analysis can also be used to help providers

synthesize the vast amounts of information that are

Part H 77.2

1386 Part H Automation in Medical and Healthcare Systems

37th week

(4055)

5.3

Admitted to NICU (%)

Gestational age

15

10

5

0

Sep-00

Nov-00

Jan-01

Mar-01

May-01

Jul-01

Sep-01

Nov-01

Jan-02

Mar-02

May-02

Jul-02

Sep-02

Oct-02

Dec-02

Feb-03

Apr-03

Jun-03

Aug-03

Oct-03

Dec-03

Feb-04

Apr-04

Jun-04

Aug-04

Oct-04

Effective inductions < 39 weeks (%)

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

38th week

(10111)

3

39th week

(15341)

2.1

40th week

(8191)

2.6

41th week

(1842)

2.9

42th week

7.3

Fig. 77.5 Results of study by Intermountain Healthcare

that analyzed almost 40 000 deliveries in 2000–2001 to

reveal an increased rate of NICU admission of babies in-

duced before week 39

available about a single patient. For a patient with mul-

tiple chronic diseases, a clinician needs to understand

the interplay of a variety of different test results and

how individual tests vary over time. Visualization tech-

niques can facilitate a clinician’s evaluation of a patient

by supporting the cognitive tasks necessary for making

judgments patient about the patient’s care. An infor-

mation system that automatically collects the relevant

information and presents it in an easy-to-read format

can significantly facilitate a clinician’s evaluation of

a patient. With such an IT system in place, the clini-

cian can work systematically from problem to problem,

rapidly focusing on the next steps and how they in-

teract. The presentation can be further augmented by

embedding relevant contextual information for any task

the clinician is handling. For example, if a provider is

ordering antibiotics thesystem would automaticallydis-

play allergies, drug interactions, previously prescribed

antibiotics, and bacterial sensitivities.

The most effective clinical information systems can

intelligently sift through vast amounts of data, identify

pertinent patient information, and synchronize seam-

lessly to a provider’s. In this setting, visualization

includes the ability to organize data based upon the

patient’s condition and determines what is and is not

relevant.

Knowledge generating systems make it easy for

physicians to focus on the pertinent positive (abnormal)

findings and the pertinent negative findings (normal re-

sults that reduce the likelihood of a specific diagnosis).

In the case of chest pain, pertinent positive findings in-

clude high cholesterol, sudden onset of pain, smoking,

and family history of coronary artery disease – all of

which suggest that the patient is at risk for a heart at-

tack. On the other hand, if the patient is relativelyyoung

with no family history of the disease, has normal lab

tests, electrocardiogram (ECG) and other vital signs,

and had similar normal findings on a recent emergency

department admission for similar pain, the physician

may conclude that coronary artery disease is an unlikely

cause.

A system without knowledge representation can

perform only limited visualization, such as simple

graphing of trends, data grids, and composite displays;

without insight into the meaning and structure of the

data there is little intelligent work that can be performed

by the computer. With knowledge representation, the IT

system can determine how the available data relates to

a patient’s active problems and then organize the entire

record to minimize the time it takes to review, increas-

ing the likelihood that the provider sees and processes

the most relevant information.

Advanced visualization algorithms can be used to

look at data in new ways. Heat maps, cluster analy-

sis, multivariate indexes such as severity scores, and

patient health dashboards all represent potential means

for presenting complicated data using simplified vi-

sual metaphors. Heat maps create color-coded views of

the patient record highlighting the most active or high-

risk areas requiring attention. Cluster analysis is used

to graphically represent the similarity between one pa-

tient and similar patients in a population. It has been

used successfully to predict patients who may be more

likely to respond to certain cancer therapies based on

the expression of different genes associated witha given

type of cancer [77.8]. Other experimental approaches

have been used to predict based on numerous factors,

which patients are more likely to develop Alzheimer

disease [77.9]. Cluster analysis is particularly useful be-

cause it enables clinicians to rapidly see associations

Part H 77.2

Automation in Hospitals and Healthcare 77.2 The Role of Medical Informatics 1387

among different factors even if the underlying scientific

principles are unknown.

Multivariate indexes, such as severity scores, com-

bine different observations about a patient into a single

score. The human mind is limited in the number of

variables it can process simultaneously by collapsing

numerous variables into a single score can make it eas-

ier for clinicians to see trends that may otherwise be

hidden in complex relationships. For example, sever-

ity scores can help clinicians identify at an earlier stage

which patients are at greatest risk for worsening illness

allowing them to intervene earlier and potentially pre-

vent the worst effects of the disease [77.10]. Patient

dashboards can be used to combine patient-specific data

and severity scores to create a prioritized list of patients,

so that the provider can quickly identify which patients

are most in need of attention. One sign of well-designed

visualization systems is that significantly fewer obtru-

sive alerts are required to avert provider mistakes; when

the data is clearly presented, users are more likely to

make the right choices the first time.

Unfortunately there are very few examples of

widely adopted systems with detailed knowledge rep-

resentation, so many of these visualization techniques

remain in their infancy.

77.2.5 Knowledge in Action

The next level of knowledge management is to take the

knowledge that has been accumulated – from medical

research, from a patient’s chart, and from data analy-

sis and visualization – and put it to work at the point

of care. Too much of the knowledge that exists today is

inaccessible to clinicians when and where they need it.

IT will build the bridge that enables us to incorporate

the extensive knowledge base into the daily activities

of patient care, resulting in a consistently high standard

of care both within and across healthcare organizations,

with fewer inappropriate variations yet still tailored

to the needs of the individual patient. When knowl-

edge is embedded into clinical workflow, clinicians are

much more likely to actually use the information than

they are to consult a static display in a book or on

a web site.

In addition to improving care of individual patients,

knowledge in action is also a keystone of continuous

quality improvement (CQI) efforts, such as the appli-

cation of Lean manufacturing principles to healthcare.

IT enables the analysis of institution-wide data to break

down processes into their constituent parts and identify

steps that do not add value to the encounter.

The translation of knowledge into action includes

digitizing informationinto a readily searchableform us-

ing knowledge representation; converting digitized data

into an electronic workflow; and organizing and updat-

ing the knowledge database once it has been created.

An institution should also rely on its IT infrastructure to

provide support reviewing outcomes measures and ef-

fectively prioritize implementation of its thousands of

evidence-based guidelines.

Knowledgeinto action can not only help institutions

apply existing evidence to the delivery of patient care,

but it also enable organizations to localize the practice

of evidence based on various populations. The insights

thus gleaned can be fed back into the system to further

refine and improve the care being provided. The Pacific

Northwest, for example, has a higher incidence of mul-

tiple sclerosis than anywhere else in the US – so when

patients present with weakness or back pain, providers

there should consider ordering an magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) sooner than they might elsewhere. This

localization caneven be applied to an individualpatient:

a person known to have a gene that predisposes him

or her to a particular disease (such as breast or colon

cancer) should be treated more aggressively than the

general population when potential symptoms are seen.

Rather than relying on a clinician to remember and ap-

ply all of these minute variations without assistance,

institutions can applyexpertrules within theirelectronic

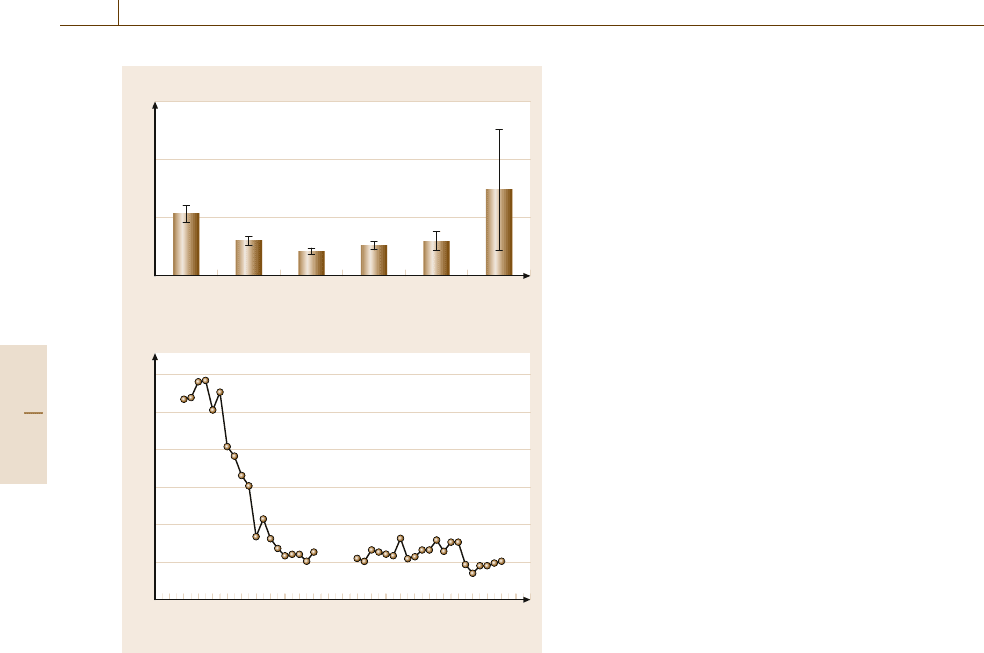

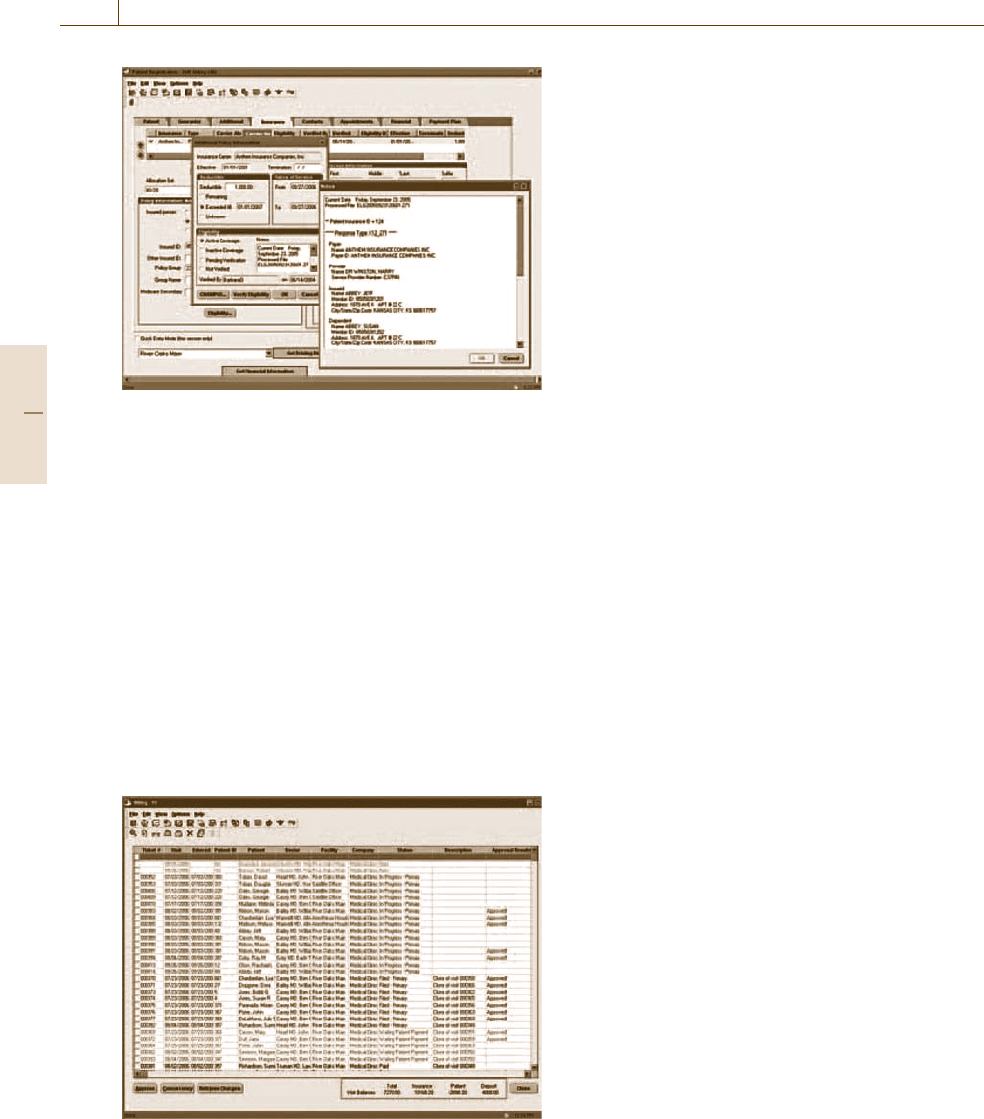

Fig. 77.6 A medical reporting tool. Technology sys-

tems like the Medical Quality Improvement Consortium

(MQIC) can be used to drive continuous quality of care

improvement by capturing current levels of quality. Using

encounter forms and decision support rules, clinicians can

then alter the effect of the care process and monitor the

result of the intervention

Part H 77.2

1388 Part H Automation in Medical and Healthcare Systems

medical record systems that will automatically present

clinicians with evidence that is most relevant to a par-

ticular patient.

One way to bring knowledge into action is through

decision support systems; of these, the most commonly

used are alert engines. These engines display messages

to users in a variety of situations, including:

•

A potentially hazardous situation, such as when

a clinician is about to order a medication to which

the patient is allergic

•

A condition that requires action, such as the receipt

of abnormal lab results

•

Missing data, such as failure to complete a list of

known allergies

•

A gap in care, such as overdue diagnostic tests rec-

ommended for preventive care of a chronically ill

patient.

Alerts are intended to be helpful, highlighting simple

issues that are easy for clinicians to overlook given the

busy nature of healthcare. The challenge is to establish

the right level of alerts. For example, the adverse ef-

fects of a drugallergy or aspecific drug/drug interaction

can have different degrees of severity depending on the

patient’s overall condition. The system would have to

determine when an alert is appropriate for a specific pa-

tient, and many systems err on the side of showing too

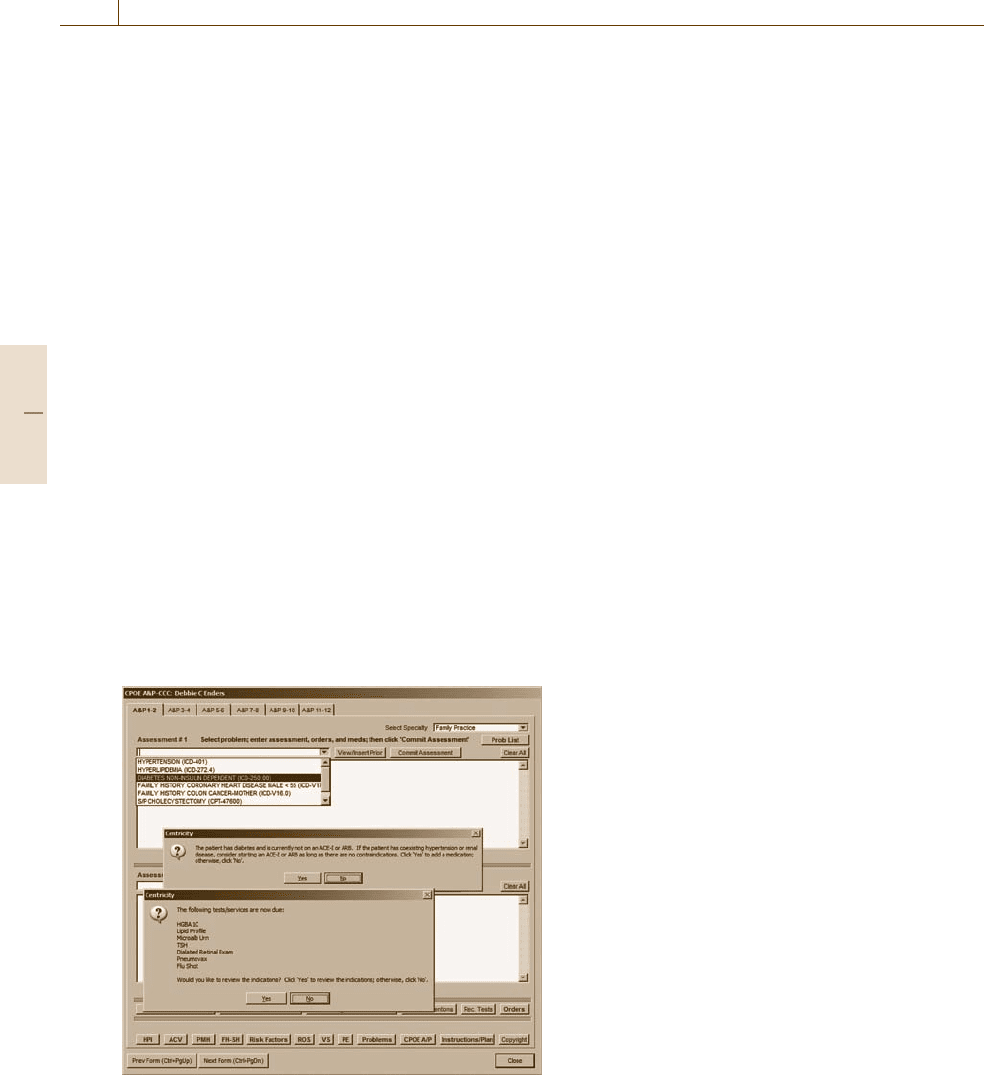

Fig. 77.7 Example of CPOE and clinical decision support.

In this example, a physicianhas beenalerted to elements of

a diabetic patient’s record, including medication manage-

ment, allergy questions, and whether to document insight

gathered from the alert

many alerts. Unfortunately, there is a threshold above

which users experience alert fatigue and begin to ig-

nore alerts – essentially rendering the alerting system

useless. In fact, some institutions turn off alerts in their

electronic medical record systems because they appear

to increase liability (if a clinician ignores an alert) with-

out changing practice.

To overcome these problems, next generation alert-

ing systems will need to have greater granularity in

how they define what triggers an alert, taking into ac-

count both the patient’s condition and the identity of

the provider. A patient with kidney disease will always

have some lab results that are outside the normal range

for the general population, but that reflect the normal

(i.e., stable) state for that individual. Similarly, alerts

regarding the management of a patient’s diabetes will

be relevant to the patient’s primary care provider, but

not to an orthopedist who is seeing the patient for an

unrelated condition.

An even more effective method of reducing alert fa-

tigue is to initially present information in a way that

reduces the likelihood of triggering an alert in the first

place. In fact, one may argue that alerts – especially

those that interrupt workflow – represent a system de-

fect. A well-designed system should instead ensure that

users do the right things rather than relying on alerts to

correct errors, and it can do this in large part by how

it displays patient data in conjunction with embedded

reference information.

In other words, a system should not need to alert

a clinician that the drug just prescribed is one to which

the patientis allergic. Instead,the listof patient allergies

should be displayed and highlighted before the clinician

even starts the medication order. An intelligent patient

summary screen would display a list of expected diag-

nostic tests based on a patient’s known problems; this

list would include the most recent results of all tests

that have already been performed, indicate which ones

need tobe repeated,and prepare(pending theclinician’s

approval) orders for tests that have not been done. In

a single glance, the clinician can easily determine the

status of the patient and the appropriate next steps that

are required.

Decision support systems are capable of more than

simple alerts. Newer decision support systems translate

existing best practice guidelines into adequately explicit

digital protocols that can be incorporated into a clinical

information system to help track and guide care.

While guidelines are common in medicine, the

terms they use are often too ambiguously defined to

be adequately represented in logic that can be enforced

Part H 77.2

Automation in Hospitals and Healthcare 77.3 Applications 1389

by a computer. A clinician will likely understand what

a guideline means if it suggests changing a medication

if a patient has not responded within a reasonable time.

In contrast, an adequately explicit version of the same

protocol would specify that if a patient’s blood pressure

has not dropped below 120/80 following administra-

tion of a maximum daily dose of 200 mg of Metoprolol

for 1 month, or if the patient’s heart rate has dropped

below 50, then the patient should be given a calcium

channel blocker.

In order to incorporate knowledge in action, there is

a significant amount of work to be done to adequately

define protocols and intelligent alerting systems. Ex-

isting guidelines tend to be written rather generically,

and need to be tailored to the specific needs of clin-

icians at a particular location. To date, much of this

work has been done by a small number of healthcare

organizations, organizations, using commercially avail-

able systems as a starting point. Because of inconsistent

terminologies and the lack of interoperability among

systems, however, another – thus, reducing or elimi-

nating the potential for synergies that could accelerate

advancement of the technology, does not easily reuse

work done at one institution. There have been a number

of attempts to create knowledge representations for pro-

tocols and alerts that could move across systems, but,

to date, none have been successfully and consistently

adopted.

Adequately explicit protocols give rise to a dia-

log over time between the provider and the computer

system that jointly determines the next appropriate in-

terventionfor care. Thefact that aprotocol isadequately

explicit, however, does not replace the need for a de-

termination to be made as to whether the protocol is

appropriate for a specific patient. A patient with kidney

failure will have changes in drug metabolism such that

some protocols should never be administered. Or a pa-

tient who starts on a particular protocol may experience

changes that make the protocol no longer appropriate.

In other words, a protocol is a method to ensure con-

sistency of care but it does not eliminate the need for

careful observation and judgment.

77.3 Applications

Existing health IT systems can be organized by func-

tions they perform and the locationswhere they perform

them. The basic functions fall into five healthcare-

separate categories: patient access, healthcare billing,

healthcare administration,clinical care, and patient con-

nectivity; a subset of these functions is then tailored

to the specific needs of a given care location. Finally

interoperability represents the functionality required to

share information across the boundaries of healthcare.

(There are a number of other core IT functions, such

as ERP or customer relationship management (CRM)

modules, which are applicable to any business and have

been adapted to healthcare, which will not be reviewed

here). Although this discussion begins with a separate

review of each function, the true power of health IT is

recognized only in enterprise systems that tie all these

functions together.

77.3.1 Patient Access

Patient access systems manage how a patient interacts

with the healthcare system; they can be further bro-

ken down into scheduling and location management.

Healthcare scheduling is complex and is key to the ef-

ficient operation of a healthcare system. The simplest

scheduling systems focus on finding a time slot for

a patient to be seen by a specific doctor in a specific

clinic. They may also take into account the level of re-

sources or services available at different times of day to

help balance the caseload. At the other end of the spec-

trum are enterprise scheduling systems, which are used

to help orchestrate the delivery of care across multiple

locations. For patients with complex conditions, these

systems ensure that appointments are scheduled in the

appropriate sequence and that a patient is not scheduled

to be in two different locations at the same time.

Location management functions, commonly re-

ferred to as patient administration message (ADT)or

admission/transfer/discharge, include tracking the loca-

tions of the patient in the hospital and storing basic

demographic information about the patient. For inpa-

tient care, the digital management of patient location is

crucial to the appropriate provision of services (know-

ing which patient in which room is to be taken for a CT

scan, for example) as well as for accurate billing.

77.3.2 Healthcare Billing

Healthcare billing systems focus on generating charges

based upon services delivered and supplies consumed,

Part H 77.3

1390 Part H Automation in Medical and Healthcare Systems

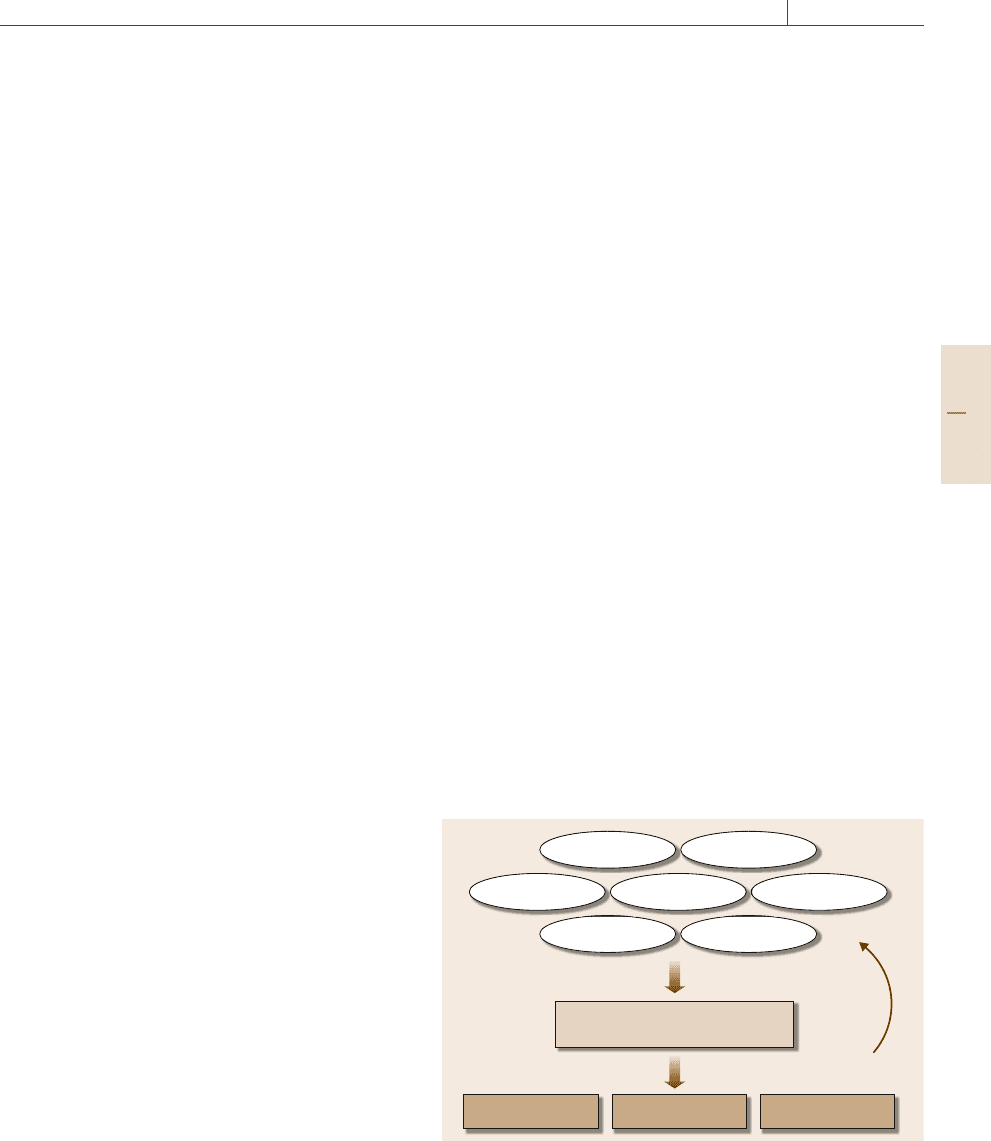

Fig. 77.8 By establishing a single electronic connection

to over 1000 payers, this healthcare application simplifies

and automates eligibility checking and claims process-

ing to help drive more efficient workflows and accelerate

reimbursement

and then presenting invoices to those responsible for

payment (whether patient, insurance company, or some

other third party). Both the capture of charges and the

billing process itself are fairly complicated in medicine.

Charges comprise both professional service fees

(incurred when a clinician performs a service for the pa-

tient) and institutional/facility fees (based on the cost of

resources consumed and the procedures performed by

the institution’s staff).

Professional service fees are codified by type and

complexity of the service provided, from a simple clinic

Fig. 77.9 Sophisticated billing solutions will include task

management, claims processing, and tools to automate in-

teractions across the healthcare systems

visit to open-heart surgery. Most IT systems capture

these charges by having doctors select specific billing

codes from a defined list.Significant training is required

for physicians to bill appropriately and legally. More

advanced IT systems provide some decision support

that reviews the doctor’s clinical documentation to help

determine the appropriate level of billing for a given

service.

For inpatient care, however, hospitals are not neces-

sarily reimbursed based upon the actual care delivered.

Instead there are DRGs (diagnostic related groups) that

typically specify reimbursement levels for specific dis-

eases or procedures; it is left up to the hospital to

manage cost so as to maintain profitability. As a re-

sult, billing systems need both cost accounting and bill

management to adequately address the address the rev-

enue cycle. Cost accounting allows institutions to track

the cost of performing basic operations and specific

care actions. Cost accounting is crucial for an institu-

tion to understand its cost structure and optimize its

productivity. Billing and revenue tracking are further

complicated because reimbursement often comes from

multiple sources: government (Medicare/Medicaid) and

insurance companies, as well as patients.

Patient billing systems focus on submitting charges

to third-party payers in such a way as to minimize rejec-

tions and shorten time to reimbursement. Increasingly,

both insurance companies and government payers typi-

cally require additionalclinical documentationto justify

the charges – increasing the demand for integration be-

tween financial and clinical systems.

Patients are responsible for all charges not reim-

bursed by either insurance or government payers. Often

there are multiple third-party payers involved, increas-

ing the complexity of billing and making the whole

process overwhelming for a patient who is also dealing

with a significant illness and looming large medical ex-

penses. A billing system that can streamline the process

and simplify the experience will have a positive impact

on patient satisfaction with the provider.

77.3.3 Healthcare Administration

Healthcare administration systems focus on the busi-

ness intelligence to understand the operations of the

healthcare system. These include financial dashboards

and reports, which show the financial operations of the

hospital, patient census and bed management, and re-

source management such as nurse staffing and order

communications (the systems that communicate order

requests within a hospital). These systems pull informa-

Part H 77.3

Automation in Hospitals and Healthcare 77.3 Applications 1391

tion from multiple sources to generate comprehensive

views of the healthcare system.

Redundant or inefficient processes can take their

toll on an organization’s bottom line. Healthcare ad-

ministration systems can help identify these processes,

enabling organizations to streamline their operations,

improving both profitability and patient and provider

satisfaction. Increasingly, healthcare administration

systems have become more dependent on clinical care.

As a result, these systems are becoming more closely

tied and potentially integrated with clinical systems.

One significant challenge for these systems is to get

clarity into details of the healthcare process especially

at the point of care. Often the point of care is the least

digitized and yet has the most significant impact on op-

erations. As the point of care becomes more digitized,

it will be easier to understand the healthcare delivery

system in detail. This will create new opportunities to

understand how cost, decision-making, and workflow

affectthe bottom line ofoperations. With greaterinsight

new rules can be built into the point of care through

standard operating procedures, workflow management,

and decision support.

77.3.4 Clinical Care

The earliest clinical systems to be adopted were ded-

icated to reviewing patients’ test results. Before the

advent of these systems, clinicians had to consult mul-

tiple sources to get the results of laboratory tests,

electrocardiograms, x-rays, and pathology reports for

a single patient. Typically the results were available to

only a few people at a time – so that different members

of the care team could not access them simultaneously

– and often the location where the results were stored

was not where the clinician was. Results-viewing appli-

cations can aggregate data from multiple sources and

allow clinicians to access the information from any-

where and at any time, so that the entire care team can

have simultaneous access to a comprehensive view of

the patient’s status.

Another area where there has been significant adop-

tion of IT is diagnostic test systems, which accelerate

the process of performing the tests and manage distribu-

tion of the results. Most hospitals now have laboratory

information systems to manage workflow, task manage-

ment, and aggregation of data for all the tests performed

in the laboratory. Likewise, picture archiving and com-

munications systems (PACS), which are used to capture

digital radiology and cardiology images from imag-

ing hardware such as digital x-rays, CT scanners, and

MRI scanners, are present at most hospitals and in-

creasingly at outpatient imaging centers. Radiologists

use PACS to view and interpret images and provide

diagnostic reports. PACS systems have eliminated the

need for large (and expensive) film storage rooms; they

have also given rise to teleradiology, where radiologists

can view and interpret images remotely. This creates

new possibilities for business models in which aca-

demic institutions can provide advanced services for

rural hospitals that may not be able to attract and sustain

specialized radiologists.

While these types of systems have been widely

adopted, they are often disconnected from the core

workflow of patient management and therefore pro-

vide little opportunity for the application of knowledge

in action. The greatest impact on improving the qual-

ity of patient care comes from clinical documentation

and computerized provider order entry (CPOE); unfor-

tunately, adoption rates for both of these functions are

less than 20% (Fig.77.10).

Orders comprise all the directions that physicians

prescribe for the management of a patient based on all

the knowledge available about that patient at a certain

point in time. Thus the amount of knowledge available

to the clinician at the time of order entry will have a sig-

nificant impact on the quality of care. CPOE not only

ensures that an order is legible and consistently commu-

nicated; it also presents the opportunity to opportunity

to use decision support to validate the appropriateness

of the order prior to it being carried out. Additionally,

CPOE allows the creation of sets of orders which can

be managed as a group to ensure a given disease is man-

aged consistently. A hospital can create a standard order

Physiologic

monitoring

Diagnostic

results

Documented

observations

Provider worklists

Physical exam Patient historyHospital course

DiagnosticsTreatments Care team actions

CPOE:

Transforming information into action

Patient response

Fig. 77.10 Example of the cycle of care with the use of clinical

documentation and CPOE

Part H 77.3

1392 Part H Automation in Medical and Healthcare Systems

set for heart attack patients and then rather than having

to remember each specific order, the physician can then

focus on changingor adding orders needed to tailor care

to the individual patient.

Order quality and order consistency were key

drivers for a recommendation by The Leapfrog Group

(a consortium of large employers concerned with

improving the safety, quality, and affordability of

healthcare) to recommend that CPOE should be widely

adopted [77.11]. The centrality of order entry to work-

flow has made it difficult, however, to design CPOE

systems that were not perceived to slow down the or-

dering process. In fact, while CPOE may create extra

steps for the physician at the time of ordering, this is

much less than the time required to correct illegible

handwritten orders or address complications that arise

from preventable adverse drug reactions. The problem

is that the physician does not directly experience the

time-saving impact of the workload.

It is only in the past few years, as organizations

have recognized the role of change management in the

success of CPOE, that adoption of these systems has

started to accelerate. One of the key success factors

has been to implement enough facets of the IT sys-

tem to demonstrate value beyond CPOE. Physicians are

more likely to adopt CPOE if at the same time they can

benefit from information access, data visualization and

decision support. Conversely, if CPOE is the only func-

tion implemented, so that workflows are split between

digital and analog systems, creating unnecessary inter-

ruptions in workflow, clinicians will be less likely to

embrace the technology.

Another key portion of a clinician’s workflow is

the documentation process. Healthcare documentation

serves four key purposes:

1. It creates a legal medical record describing both the

reasoning and activities involved a specific patient’s

care.

2. It provides a basis for outcomes analysis, population

management, and reporting.

3. It communicates one care team member’s actions

and reasoning to other members of the care team,

enabling better collaboration and coordination of

care.

4. It assists clinicians to organize their thoughts and

plan their actions.

Thus, good documentation systems are more than

just sophisticated word processors. Rather, these sys-

tems are important for legal accountability, retrospec-

tive data analysis, and data mining, as well as for

orchestrating and coordinating the ongoing work of the

entire care team.

Interdisciplinary documentation, integration of de-

cision support, and integration of key workflow tasks

all contribute to extending the value of these systems.

It is rare that one provider is responsible for all of

the information necessary to manage a single patient.

Interdisciplinary documentation allows providers from

different specialties and disciplines to contribute to the

medical record in an orchestrated fashion, collaborating

on shared documents and leveraging documents created

by others. Each provider can see the work performed

by others and integrate other providers’ observations

into their own work. The hospital physician who sees

a patient once per day relies on the information from

hundreds of encounters by nurses, dieticians, physical

therapists, and social workers to write one note that sets

the direction for the next day of patient care. Similarly,

a case manager will integrate the work of the entire care

team and synchronize the nursing, physician, patient,

and discharge goals all based on the shared documen-

tation of the team.

The more powerful documentation systems com-

bine task and worklist management features to tie the

work of documentation into the details of patient care.

Because documentation is such a consistent part of

healthcare delivery, incorporation of worklists into the

documentation process tends to increase the consistency

of care delivery.

Providers often use documentation as an important

part of their cognitive process, using it to help orga-

nize the information available and form their plan of

action. The basic structure of a progress note taught

to all physicians is called SOAP, which stands for

subjective, objective, assessment, and plan. Thus, the

inherent structure of the note is designed to aggregate

current knowledge about a patient, assess the patient

and then determine the plan of care. Most documen-

tation notes follow a similar structure. Preserving this

cognitive value of documentations is one of the hard-

est problems to solve in digitizing the documentation

process.

Because, as with CPOE, so much reasoning oc-

curs during the process of writing notes, documentation

is another key target for decision support systems.

Decision support can both initiate the documentation

process and occur within the documentation process

itself. Decision support initiated documentation fo-

cuses on dynamically manage managing the task or

action that should occur next. Documentation also be-

Part H 77.3

Automation in Hospitals and Healthcare 77.3 Applications 1393

comes the final step and forcing function to make

sure that a process actually occurs. During docu-

mentation, decision support is used to automatically

aggregate information that should be included in the

note and prompt for actions that should be considered

within the care plan. Documentation links task manage-

ment, results review, care planning, decision support,

and order entry all into a single workflow. The best

documentation systems are built to leverage and dy-

namically interact with all of these functions within the

EMR.

One of the next important trends in clinical applica-

tions is near device decision support. Medical devices

are sprinkled across the healthcare system. There are

advanced physiologic monitors and ventilators in the

intensive care unit, anesthesia machines in the operat-

ing room, ECG machines in the emergency department,

blood pressure cuffs and intravenous infusion pumps al-

most everywhere, and new devices entering the home –

just to name a few. These devices each have their own

innovations and manufacturers seek to find unique and

innovative ways to differentiate their products. As a re-

sult these manufacturers have targeted ways to make

these devices ubiquitous indispensable parts of the care

process. Extending the hardware platform at the core

of these devices with new software applications that

aid in the care process has become increasingly com-

mon. Many of these applications can be considered

near device decision support, as the decision supporting

characteristics are managed by the device rather than

with a clinical information system. For example many

new infusion pumps include the ability to check dose

ranges and verify the barcode of medications before

they are administered. In fact, some of these pumps will

connect to pharmacy information systems to allow the

pharmacist to directly program the pumps wirelessly.

Even more advanced applications are starting to ap-

pear such as ventilators that have embedded weaning

protocols that help guide the process of discontinuing

the use of mechanical ventilation in critically ill pa-

tients. (Ventilatorsare machinesthat breathe for patients

when they are too sick to breath for themselves. One of

the challenges of using a ventilator is helping a patient

gain the strength to breathe independently of the ma-

chine as they begin to improve. This process is called

weaning.) There are numerous applications where soft-

ware combined with medical devices will help manage

complicated and specific care processes. In this space

the line between devices and software will begin to

blur.

77.3.5 Patient Connectivity

In a given year most people may see their doctor at most

1h and even patientswith allbut the most severedisease

spend most of their time living their lives independent

of the healthcare system. As a result most of the deci-

sions that affect the health of a person are made during

the activities of daily life. Choices about diet, exercise,

medication compliance, sleep habits, and stress levels

all contribute significantly to the real health outcomes

that face society. If we are to truly improve the health

of a population then we must enable the healthcare sys-

tem to reach beyond the boundaries of its wall directly

into the lives of patients. Essentially, the patient be-

comes the central memberof the care team and effective

collaboration becomes key.

With the advent of increased penetration of the In-

ternet into the average family household and increased

trends toward patient financial responsibility for health-

care due to employers passing the increase costs of

healthcare on to their employees, the patient’s role in

the IT system has begun to expand.

The most common and demanded IT functions are

around managing the patient’s access and finances with

an institution. Many systems are beginning to allow

patients to request appointments online and allow pa-

tients to review their complicated billing histories and

make payments. Thesefeatures keep healthcare systems

on par with other industries and increase the customer

satisfaction of interacting with the healthcare system.

Additionally, since these portals receive a fair amount

of traffic healthcare, institutions use these portals to pro-

vide marketing and relevant institutional information to

patients and prospective patients. This is particularly

important inurban areaswhere healthcaresystems com-

pete for market share.

Although these finance and access features drive

a great deal of consumer satisfaction they have limited

impact on the health of a patient. Recently, EMR ven-

dors and dedicated patient portal vendors have begun

providing clinically oriented applications. The simplest

forms of this application allow patients access to por-

tions of their medical record – such as labs and results –

and allow secure communication with between the pa-

tient and the physician. These e-Visits have recently

begun to be reimbursed by payers as they are becom-

ing more effective and reducing unnecessary and more

expensive office visits.

More advanced versions of these applications in-

clude true disease management applications, which

Part H 77.3

1394 Part H Automation in Medical and Healthcare Systems

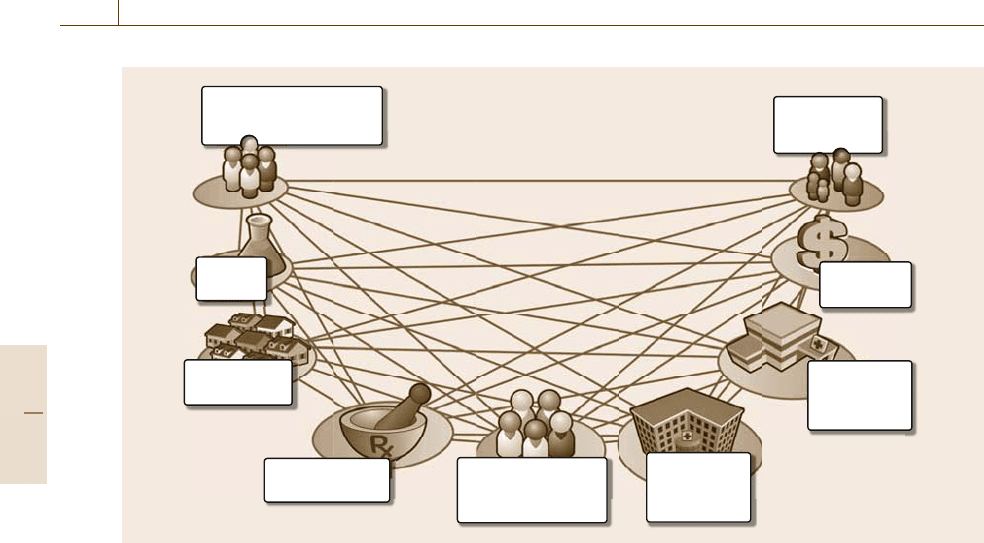

Primary care physicians

• Practice management

• EMR

Lab

• Results

Pharmacy/PBMs

• Rx history

Payers

• Claim data

Public health

• Registries

Speciality practice

• Practice management

• EMR

Patient

• Personal

health records

Hospital 2

• EMR/PMs

• Lab

• PACS archive

Hospital 1

• EMR/PMs

• Lab

• PACS archive

Fig. 77.11 Automation has a crucial role in how frequently a patient will interact with the healthcare system based on

complexity of the experience and how a patient will retrieve healthcare information beyond the episodes of care

allow physicians and/or care managers to interact with

populations of patients to manage specific diseases

such as diabetes, asthma, and congestive heart failure.

These application extend the clinical feature to include

registries of patients with key clinical information to

highlight which patients need help from the healthcare

system and provide tools to enable collaboration with

the patient on a shared plan of care for their diseases.

While these clinical applications tend to be pro-

vided by providers thereis another class ofwellness and

disease management applications that are provided by

insurers and employers. These applications share some

of the same features described above but also include

applications to inspire health behaviors in populations

in consumers. These programs have been shown to re-

duce the costs of healthcare for employers and reduce

the cost of managing populations for insurers.

Finally people are beginning to take more control

of their own healthcare records and there has been

an emergence of digital personal healthcare records

(PHRs). These personal healthcare records allow peo-

ple to record their key clinical information such as labs,

diet, exercise, medication lists, etc. Some PHRs can

connect to EMRs and directly share information be-

tween patients and providers. Some PHRs also include

wellness and disease management features to link the

patients personal data with activities that drive health

and wellness.Although PHRs offer opportunities to em-

power patients, increase sharing and collaboration, and

drive better healthbehaviors,their adoptionremains low

while commercial interest remains high.

77.3.6 Interoperability

Despite the successful digitization and automation of

the workflows within many global locations, most in-

formation is stored in silos and is unable to provide

maximum impact on patient care. Unfortunately, it’s

often at the same boundaries that prevents digital infor-

mation flow from improving quality and safety reside.

For example, when a patient is discharged from the hos-

pital it is most common that medication changes and

follow up plans are confused. It is also at discharge

when a new set of healthcare providers will manage the

patient and often these healthcare providers do not have

a mechanism for accessing the digital patient record

if it is present. Interoperability strategies seek to im-

prove this flow of information. Within the US there

are strategies to create regional health information or-

ganizations (RHIOs) that can manage the exchange of

critical information across these institutional bound-

aries. At a national level there are plans to develop

Part H 77.3