Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

GEOTHERMIC CHARACTERISTICS OF SEDIMENTS AND SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 315

Table G6 Average heat-production values of some igneous rocks

(from Haenel, Ryback, and Stegena, 1988, p. 136)

Table C8 Thermal conductivities of some sedimentary rocks (from

Blackwell and Steele, 1992; lessop, 1990)

Rock type Heat production Rock type Conductivity range (W/mK)

Granite

Granodiorite/dacite

Diorite, quartzdiorite/andesite

Gabbro/basalt

Peridotite

Dunite

Table G7 Representative heat generation units (HGUs) for sediments/

sedimentary rocks (Haenel, Rybach, and Stegena, 1988, p. 136)

2.45

1.48

1.08

0.309

0.012

0.002

Limestone

Dolomite

Sandstone

Clay and siltstone

Shale

Anhydrite

Basalt

Granite

2.50-3.10

3.75-6.30

2.50-4.20

0.80-1.25

1.05-1.45

4.80-5.80

4.80-6.05

1.69-1.96

307-3.50

Rock type Heat production

Limestone

Dolomite

Quartzitic sandstone

Arkose

Graywacke

Shale and siltstone

Black shale

Salt

Anhydrite

0.62

0.36

0.32

0.84

0.99

1.80

5.50

0.012

0.090

The heat (H), partly generated by the radioactive isotopes of

Uranium (U), Thorium (Th), or Potassium (K), is dissipated

through the crust and overlying sediments or sedimentary

rocks and is measured in |iWm~". The heat is transmitted by

conduction, convection, or radiation. The amount of heat,

timing, and cause of heating is of prime importance to many

geological applications such as understanding cratonic sedi-

mentary basin development, generation and migration of

petroleum, emplacement of ore deposits, and sedimentary

diagenesis.

Igneous and metamorphic rocks which constitute the

Earth's crust are naturally radioactive and have different

heat-production rates. For example, granites usually contain

more radioactive elements than gabbros and basalts. Some

representative values are given in Table G6.

Some heat may be generated by radioactive elements within

the sediments themselves (Table G7). For example, black

shales may be highly radioactive, but other rock types such as

limestones and sandstone contain few radioactive elements,

except in special conditions, and, therefore, their heat

generation unit (HGUs) values are small. Evaporites essen-

tially are devoid of any radioactive elements and therefore the

HGUs are extremely small or nil. The radioactive sediments,

of course, contribute to the overall heat flow, but generally this

contribution is small (because of the thinness of the

sedimentary package) relative to the basement rocks (= crust),

which constitute infinitely more mass.

The heat flow in sedimentary basins, for the most part, is

computed from temperatures measured in boreholes, usually

drilled for purposes other than measuring temperature. A vast

amount of these data are available as bottomhole temperatures

(BHTs) or temperatures taken in drillstem tests (DSTs) during

logging of commercial wells drilled in search of petroleum, ore

deposits, or water. Temperatures also may be recorded in well

bores by conventional continuous temperature logging tech-

niques or by the new Distributed Optical-Fibre Temperature

Sensing technique (DTS). Temperatures measured during well

logging may be of questionable value depending on the

circumstances and conditions during their recording and

collection. If certain conditions are known and controlled,

then the values can be corrected to obtain a 'true' temperature.

Topography

In lowland areas or areas with little topographic

relief,

a

correction for topographic irregularities is not needed. In other

areas with considerable topographic

relief,

however, a correc-

tion factor needs to be applied.

Rock type and conductivity

Different rock types exhibit different thermal conductivities

and these values have been measured carefully in laboratories

under controlled conditions. A summary of values is presented

in Table G8.

Porosity and contained fluid or gas

The type of fluid or gas contained in pores of a rock affect their

conductivity and thus the computation of any value dependent

on the thermal conductivity (Table G8). Water, oil, or natural

gas all have different conductivities and alter the overall rock

conductivity, but usually the interporosity substance is known

and can be considered in the computations.

Past climatic conditions

This factor affects only the upper hundred meters or so of the

subsurface and the effect can be determined from any reliable

temperature log taken in a borehole. The correction for the

climatic change is relatively small, but could be important,

especially in areas of permafrost.

The computed heat-flow values, then, can be compared

from one location to another, plotted on a map, and contoured

for further interpretation (see for example Blackwell and

Steele, 1992; Cermak and Hurtig, 1979; Hamza and Munoz,

1996).

For reference, the average heat flow on continents is

approximately 62 mWm^ and for oceanic areas, it is slightly

higher at about 80 mWm^ (Jessop, 1990, p. 205).

Daniel F. Merriam

316

GLACIAL SEDIMENTS: PROCESSES, ENVIRONMENTS AND FACIES

Bibliography

Blackwell, D.D., and Steele, J.L. (eds.), 1992. Geothermal map of

North America.

Geological

Society of America, Map CSM007; scale:

1:5,000,000.

Cermak, V., and Hurtig, E., 1979. Heat flow map of Europe. In

Cermak, V., and Rybach, L., (eds.). Terrestrial Heat

Flow in

Europe.

Springer-Verlag, pp. 3-40.

Haenel, R., Rybach, L., and Stegena, L., 1988. Handbook of Terrestrial

Heat-flow Density Determination. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Hamza, V., and Munoz, M., 1996, Heat flow map of South America.

Geothermics, 25(6): 599-646.

Jessop, A.M., 1990. Thermal

Geophysics.

Elsevier.

GLACIAL SEDIMENTS: PROCESSES,

ENVIRONMENTS AND FACIES

Introduction

Significance of glacial deposits

The importance of glacial sediments can be gauged from the

fact that 10 percent of the Earth's land surface currently is

covered by glacier ice, a figure that exceeded 30 percent during

the Quaternary glaciations of the last 2 Ma. Glacier ice has left

a complex, often patchy, record of deposition on land, and

offshore has contributed substantially to the build up of

continental shelves. In earlier geological history, the Earth

experienced several continental-scale glaciations, some of them

even more extensive than those of the Quaternary Period.

Glacial deposition is intimately associated with a wide range

of other processes, including fluvial, mass flowage, eolian,

lacustrine, and marine. The resulting facies associations are

highly variable, and without detailed investigation can be

subject to a wide range of interpretations. It is only within the

last three decades that studies of glacial processes in modern

settings have made it possible to develop plausible models of

past glacial depositional environments.

Understanding the nature of Quaternary glacial sediments

and their associated landforms is vital in glaciated areas of

North America and Europe, where sand and gravel extraction

is essential for construction purposes, and for sensible

management of water resources and waste disposal. Ancient

glacial deposits and associated facies are also economically

important; in some regions, since they control the presence of

petroleum resources, as for example in the Permo-Carbonifer-

ous and Neoproterozoic sequences of the Middle East and

South America.

Historical background

Today, it is common knowledge that the Earth experienced a

series of ice ages but, when the concept was first mooted in the

early 19"' century, it met with fierce opposition, as most of the

unconsolidated deposits {drift) that are familiar to geologists

were attributed to Noah's flood of the Old Testament, often

with the proviso that larger boulders ("erratics") were

deposited from icebergs (Hambrey 1994, Chapter

1

for review).

The Swiss natural historian, Agassiz, became the chief

protagonist of the "Ice Age Theory", and when he delivered

his ideas in 1837, they had a Europe-wide impact. In the

following decades, through Agassiz's influence, geologists in

the UK and North America gradually accepted the theory as

being applicable to their areas. In the second half of the 19"'

century, "ancient" glacial deposits (tillites) were recognized in

many parts of the world. However, even in the second half of

the 20"^ century, the glacial origin of supposed tillites was

challenged, notably those of Neoproterozoic age. It has taken

systematic sedimentological investigations, coupled with an

appreciation of modern glacial processes, to settle these

debates.

Extent of glacier ice today

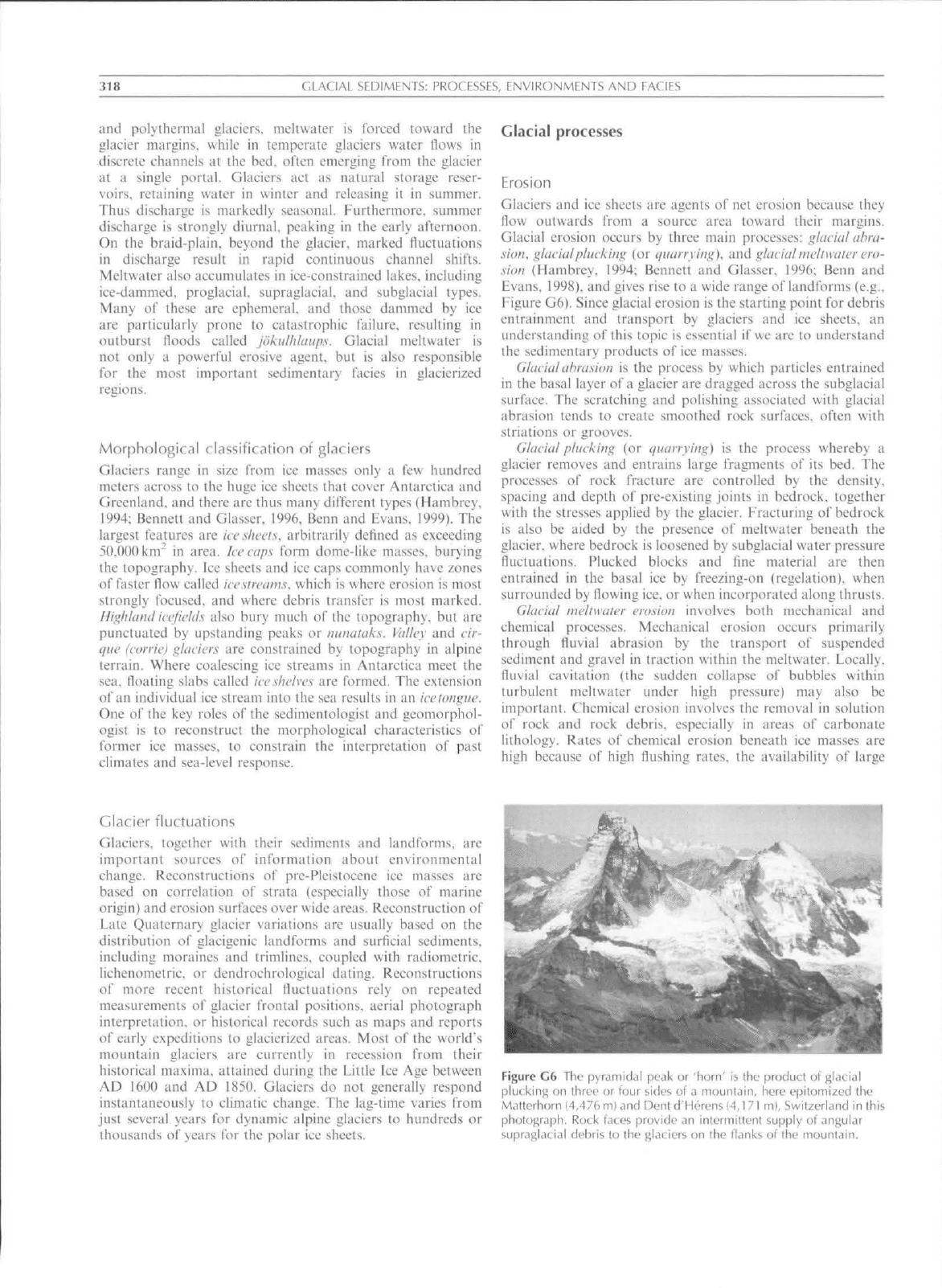

The areal extent of glacier ice today has been documented by

the World Glacier Monitoring Service (1989) (Table G9). By

far the greatest expanses of ice are the ice sheets of Antarctica

(85.7 percent of area) and Greenland (10.9 percent). However,

it is the remaining 3.4 percent that impinges directly on human

civilization, and most detailed sedimentological studies have

focused on these smaller ice masses. The potential contribution

of the Antarctic ice sheet to sea level rise is 56 m, with the

Greenland ice sheet adding a further

7

m. The remaining

glaciers account for a mere fraction of

this.

Fluctuations of the

world's ice masses continue to affect global sea levels,

providing on-going eustatic controls on the sedimentary

processes on continental shelves.

Characteristics of glaciers

Mass balance

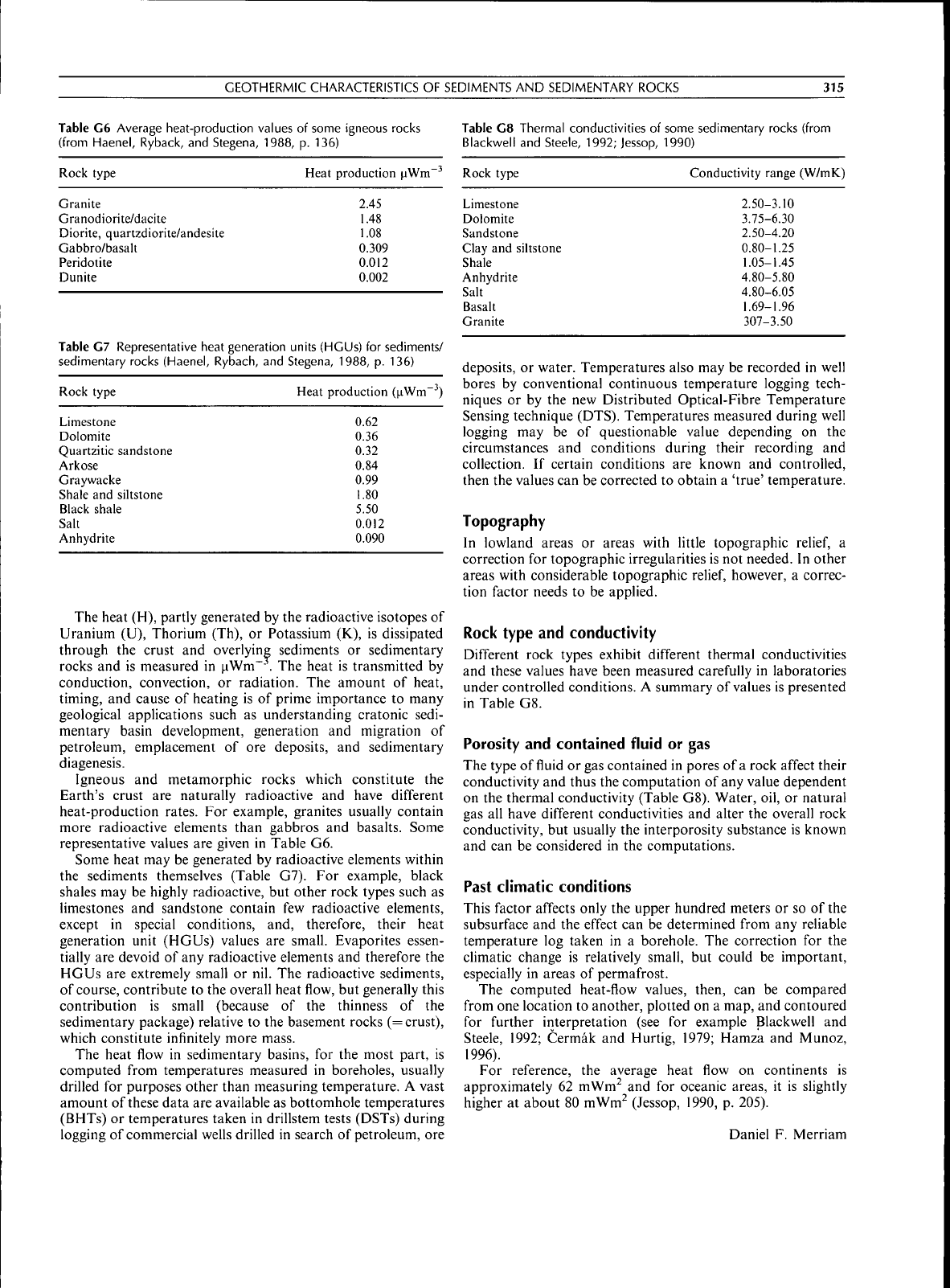

The state of health of a glacier is a reflection of the balance

between accumulation and ablation over periods of decades to

hundreds of years, or thousands of years in the case of the

polar ice sheets. The difference between accumulation and

ablation in any one year is referred to as mass balance, which is

positive if accumulation exceeds ablation and negative if the

reverse. Accumulation mainly takes the form of snow, which is

transformed or metamorphosed by burial, through firn, to

glacier ice. Ablation is largely accomplished by melting on

temperate glaciers, while in some regions calving from ice

masses into the sea accounts for the bulk of ice losses. Glaciers

are typically subdivided into an accumulation zone and an

ablation zone, separated by an equilibrium line where there is

no net gain or loss of mass (Figure G4).

Table G9 Distribution of glacierized areas of the world

(World Glacier Monitoring Service, 1989)

Region

Africa

Antarctica

Asia and Eastern Europe

Australasia (i.e.. New Zealand)

Europe (Western)

Greenland

North America excluding Greenland

South America

World total

Area (km^)

10

13,593,310

185,211

860

53,967

1,726,400

276,100

25,908

15,861,766

GLACIAL SEDIMENTS: PROCFSSES, ENVIRONMENTS AND EACIES

317

borehoie before

displacement

borehole atler

displacemenl

snow accumulation Equlllbfium line

Ablation area

V

"^

'**':>-

net

loss

meiting ice

Bedrock ' ^ ^ - v- -.

giacier

shout

Figure C4 Longitudinal profile through a valley glacier, illustrating

flow lines (particle paths) in relation to the equilibrium line.

Glacier dynamics

In order to interpret the origin of glacial sediments and

landfonns. it is necessary to understand the mechanisms of ice

derorniation and glacier flow. Glaciers flow by one or more of

three main mechanisms: internal delormation, basal sliding,

and movcmenl over a soft, deformablc bed (Patcrson. 1994).

inlcniiil lUjornuitioii is best explained by Glen"s flow law for

poiyerystalline ice; this law relates the effective shear-strain

rate

(J:)

to shear stress

(T)

in the following equation:

J: = Ax"

where n is a eonstant, typically 3. and A depends on ice

temperature, erystal size and orientation, and impurities.

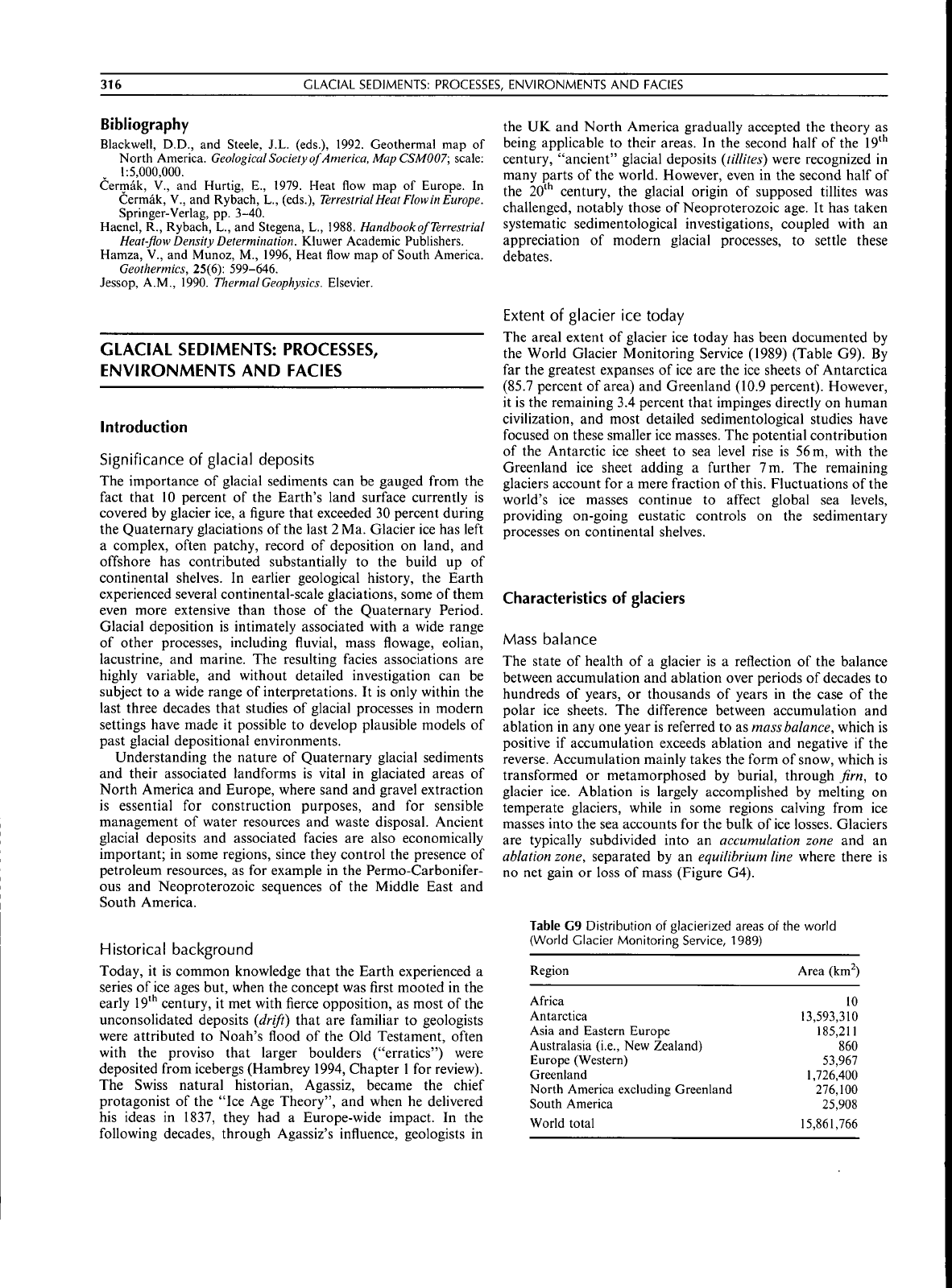

Internal deformation results in the slowest llow occurring at

ihe surface and at the base of a glacier (Figure G5). Basal

s/idiiiy is important where rain or melt-water is able to

lubricate the bed (Figure G5), and varies according to the

season and time of day or night. Frictional and geothermal

heating may add to the availability of meltwater. Many

glaciers flow over a bed of unconsolidated sediment which,

when saturated, is readily deformed. Deformable beds exist

beneath modern fast-flowing ice streams in Antarctica. Much

of ihe movement of the Quaternary ice sheets in North

America, has also been linked to subsole deformation. The

relative importance of these mechanisms is highly variable. In

moist temperate regions as much as 80 percent of glacier flow

is from sliding. Cold polar glaciers, which are frozen to their

beds,

flow almost entirely by internal deformation. Where a

deformable bed exists, the bulk of movetneni may be within

the sediment layer beneath the ice. In surgc-ivpeglaciers, flow

is unstable, uith long periods (often decades) of quiescence

punctuated by short bursts (several months to a few years) of

high velocity {surges). At its peak, the velocity may reach

several orders magnitude above normal, and the glacier may

advance rapidly, and redistribute large volumes of sediment.

Glacier structure

Glacier structures are principally the product of internal

deformation, and are intimately associated with the transport

of debris. Glacier ice is similar to any other type of geological

material in that it comprises strata that progressively deform

A

-

basal sliding component

B

-

inlernal deformation component

Figure G5 Vertical longitudinal profile through a glacier, illustrating

tht.' two miiin components of f}M ier flow, internal deform.iti()n

and basal sliding. Arrows indicate relative displacements, as

determined from borehole studies.

to produce a wide range of structures. Primary structures

include sedimentary stratification derived from snow and

superimposed ice, unconformities, and regelation layering

resulting from pressure melting and refreezing at the base of

a glacier. Secondary structures are the result of deformation,

and include both brittle features (crevasses, crevasse traces,

faults and thrusts) and ductile features (foliation, folds,

boudinage). Typically, a glacier reveals a sequential develop-

ment of structures as in deformed rocks, so that by the time the

glacier snout is reaehed. ice may reeord several phases of

deformation.

Thermal regime

The temperature distribution or ifwrmal regime of a glacier

is fundamental to glacier llow, meltwater production and

routing, and to styles of glacial erosion and deposition. The

most active glaciers are so-called it'mperiilf or warm, in which

the ice is at the pressure-melting point throughout. These

glaeiers slide rapidly on their beds and induce much erosion;

they are typical of alpine regions. At the opposite end of the

spectrum are cokl glaciers, which are below the pressure

melting point throughout. Since they are frozen to the bed,

cold glaciers are generally regarded as having little ability to

erode, although this assumption has been challenged by

observations in the Dry Valleys of Antarctica recently. An

intermediate type of glacier, found in the High-Arctic, is

referred to as pa/yihermal. In sueh glaciers, it is typieal for the

snout, margins and surface layer of the glacier to be below the

pressure-melting point, whereas thicker, higher level ice is

warm-based.

Glacier hydrology

Meltwater within, beneath and beyond glaeiers plays a vital

role in the processes of erosion and deposition. Water, derived

from melting snow and ice, flows in channels on the glacier

surface, until plunging via moulins into {he interior or bed of

the glacier, finally emerging at the snout. Drainage routes

differ according to the thermal regime of the glacier. In cold

318

C;LACIAL

SEDIMENTS: PROCESSES, ENVIRONMENTS AND EACIES

and polythermal glaciers, meltwatcr is forced toward the

glacier margins, while in temperate glaciers water flows in

discrete channels at the bed. often emerging from the glacier

at a single portal. Glaeiers act as natural storage reser-

voirs,

retaining water in winter and releasing it in sitmiiier.

Thus discharge is markedly seasonal. Furthermore, summer

diseharge is strongly diurnal, peaking in the early afternoon.

On the braid-plain, beyond the glacier, marked fluctuations

in discharge result in rapid continuous channel shifts.

Mcltwater also accumulates in ice-const rained lakes, including

ice-dammed. proglaciaL supraglacial, and subglacial types.

Many of these are ephemeral, and those dammed by iee

are particularly prone to catastrophic failure, resulting in

outburst floods ealled joktilhlaups. Glacial meltwater is

not only a powerful erosive agent, but is also responsible

for the most important sedimentary facies in glacierized

regions.

Morphological classification of glaciers

Glaciers range in size from ice masses only a few hundred

meters across to the huge ice sheets that eover Antarctica and

Greenland, and there are thus many different types (Hanibrey,

1994;

Bennett and Glasser, 1996, Benn and Evans, 1999). The

largest features are keslwets. arbitrarily defined as exceeding

50,n00knr in area. Icecaps form dome-like masses, burying

the topography. Ice sheets and ice caps commonly have zones

of faster flow ealled iccsircams. which is where erosion is most

strongly focused, and where debris transfer is most marked.

IliiihUindiccfifUis also bury much of the topography, but are

punctuated by upstanding peaks or minataks. Valley and cir-

que (corrie) glaciers are constrained by topography in alpine

terrain. Where eoaleseing ice streams in Antaretica meet the

sea. floating slabs called

ice shelves

are formed. The extension

of an individual ice stream into the sea results in an iccioiiguc.

One of the key roles of the sedimentologist and geomorphol-

ogist is to reconstruct the morphological characteristics of

former ice masses, to constrain the interpretation of past

climates and sea-level response.

Glacial processes

Erosion

Glaciers and ice sheets are agents of net erosion because they

flow outwards from a source area toward their margins.

Glacial erosion occurs by three main processes: glacial ahra-

sion.

glacial plucking (or iiuarrying). and glacial mclimiier ero-

sion (Hambrey. 1994; Bennett and Glasser. 1996; Benn and

Evans. 1998). and gives rise to a wide range of landtbrms (e,g..

Figure G6). Since glacial erosion is the starting point for debris

entrainmeni and transport by glaciers and ice sheets, an

understanding of (his topic is essential if we are to understand

the sedimentary products of ice masses.

Glacial

abrasion is the process by which particles entrained

in the basal layer of a glacier are dragged across the subglacial

surface. The scratching and polishing associated with glacial

abrasion tends to create smoothed rock surfaces, often with

striations or grooves.

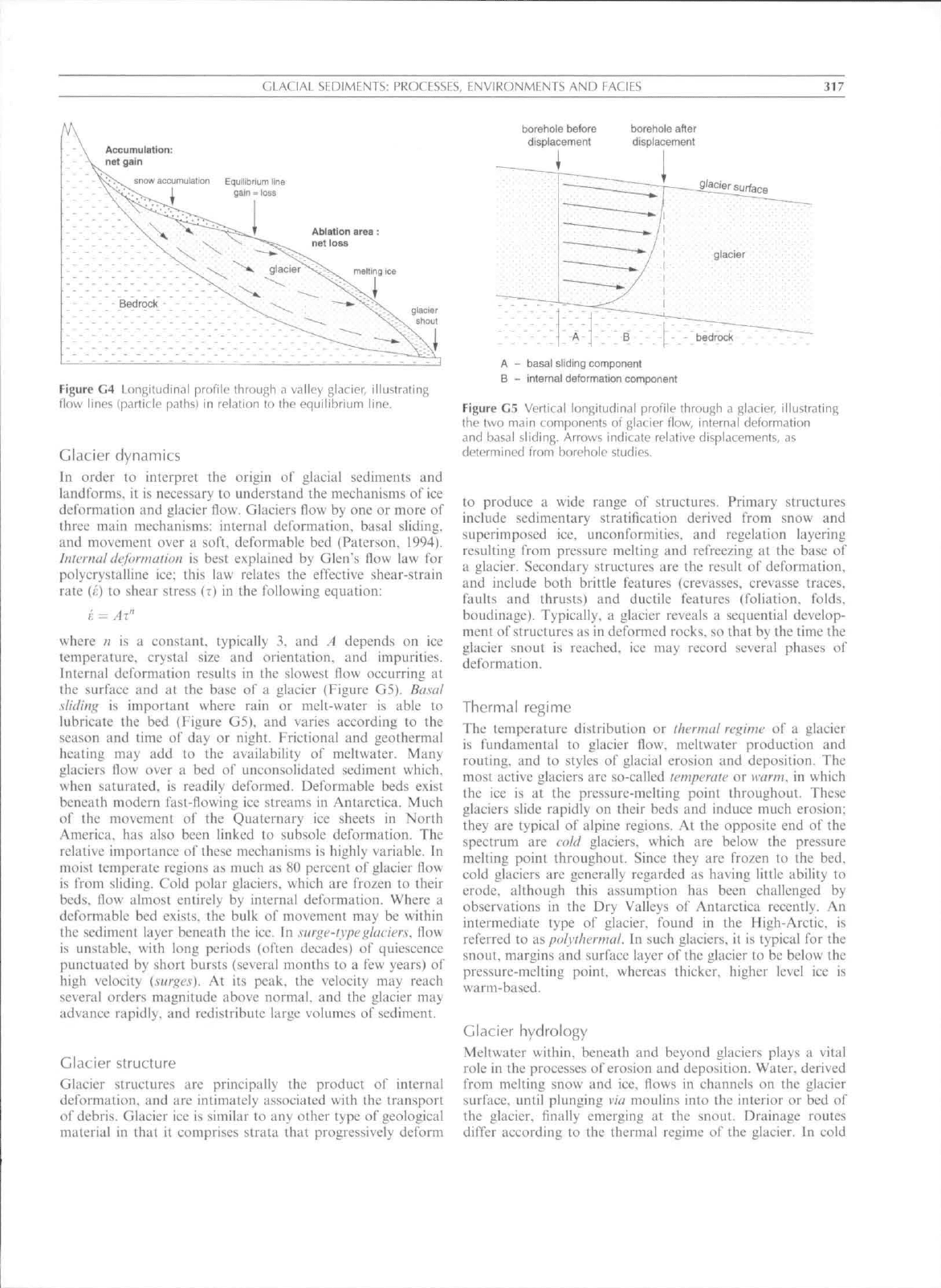

Glacial plucking (or quarrying) is the process whereby a

glacier removes and entrains large fragments of its bed. The

processes of rock fracture are eonlrolled by the density,

spacing and depth of pre-existing joints in bedrock, together

with the stresses applied by the glacier. Fracturing o\' bedrock

is also be aided by the presence of meltwater beneath the

glacier, where bedroek is loosened by subglacial water pressure

fluctuations. Plucked blocks and fine material are then

entrained in the basal ice by freezing-on (regelation). when

surrounded by flowing ice. or when incorporated along thrusts.

Glacial meliwaler erosion involves both meehanical and

chemical processes. Meehanical erosion occurs primarily

through fluvial abrasion by the transport of suspended

sediment and gravel in traction within the meltwater. Loeally.

fluvial cavitation (the sudden collapse of bubbles within

turbulent meltwater under high pressure) may also be

important. Chemical erosion involves the removal in solution

of rock and rock debris, especially in areas of carbonate

lithology. Rates of chemical erosion beneath ice masses are

high because of high flushing rates, the availability oi large

Glacier fluctuations

Glaciers, together with their sediments and landforms, are

important sources of information about environmental

change. Reconstructions of pre-Pleistocene ice masses are

based on correlation of strata (espeeially those of marine

origin) and erosion surfaees over wide areas. Reconstruction of

Late Quaternary glacier variations are usually based on the

distribution of glacigenic landforms and surficial sediments,

including moraines and trimlines, coupled with radiometric.

lichenomctric, or dcndrochrological dating. Reconstructions

of more recent historical iUictuations rely on repeated

measurements oT glacier fiontal positions, aerial photograph

interpretation, or historical records such as maps and reports

of early expeditions to glacierized areas. Most of the world's

mountain glaciers are currently in recession from their

historical maxima, attained during the Little Ice Age between

AD 1600 and AD 1850. Glaciers do not generally respond

instantaneously to climatic change. The lag-time varies from

just several years for dynamic alpine glaciers to hundreds or

thousands of years for the polar ice sheets.

Figure G6 The |j}i"diiiiiljl peak ur

iiorn'

ib llic produti ol gljuJdl

plu(

kirij^

on three or four sides of

<i

mountain, here epitomized the

Malterhorn (4,476 ni) and Dent d'Herens

(4,1 71

m|, Switzerland in this

phulugraph. Ruck foces provide an intermittent supply of angular

lidl debris to the fjLiciers on the flanks of the mountain.

GLACIAL SEDIMENTS: PKOCES.SES, ENVIRONMENTS AND EACIES

319

amounts of chemically-reactive rock flour, and the enhanced

solubility of CO: iit low temperatures.

To these three main processes we may add a fourth: the

relatively poorly understood process of suhglacial sctlinicni

dcformalion. Sediment deformation beneath ice sheets con-

tributes to glacial erosion wherever there is a net removal o\

material from the bed durina sediment deformation (Boulton,

1996).

Debris entrainmeni and transport

It is widely recognized that debris is incorporated mainly at the

bed and on the surface of a glacier, and that the transport

paths and textural character of glacial sediments are related to

ihe dynamic and thermal characteristics of the glaeier. In

general terms, polythermal glaciers tend to carry a high basal

debris load, and ihcir surfaces rarely have a substantial cover

of debris. In contrast, temperate glaciers, especially those in

alpine terrain, nortnally carry little debris at the bed. but their

surfaces commonly have extensive areas of supraglacial debiis.

The resulting sedimentary products can thus be used to infer

the thermal and topographic regimes of the glacier.

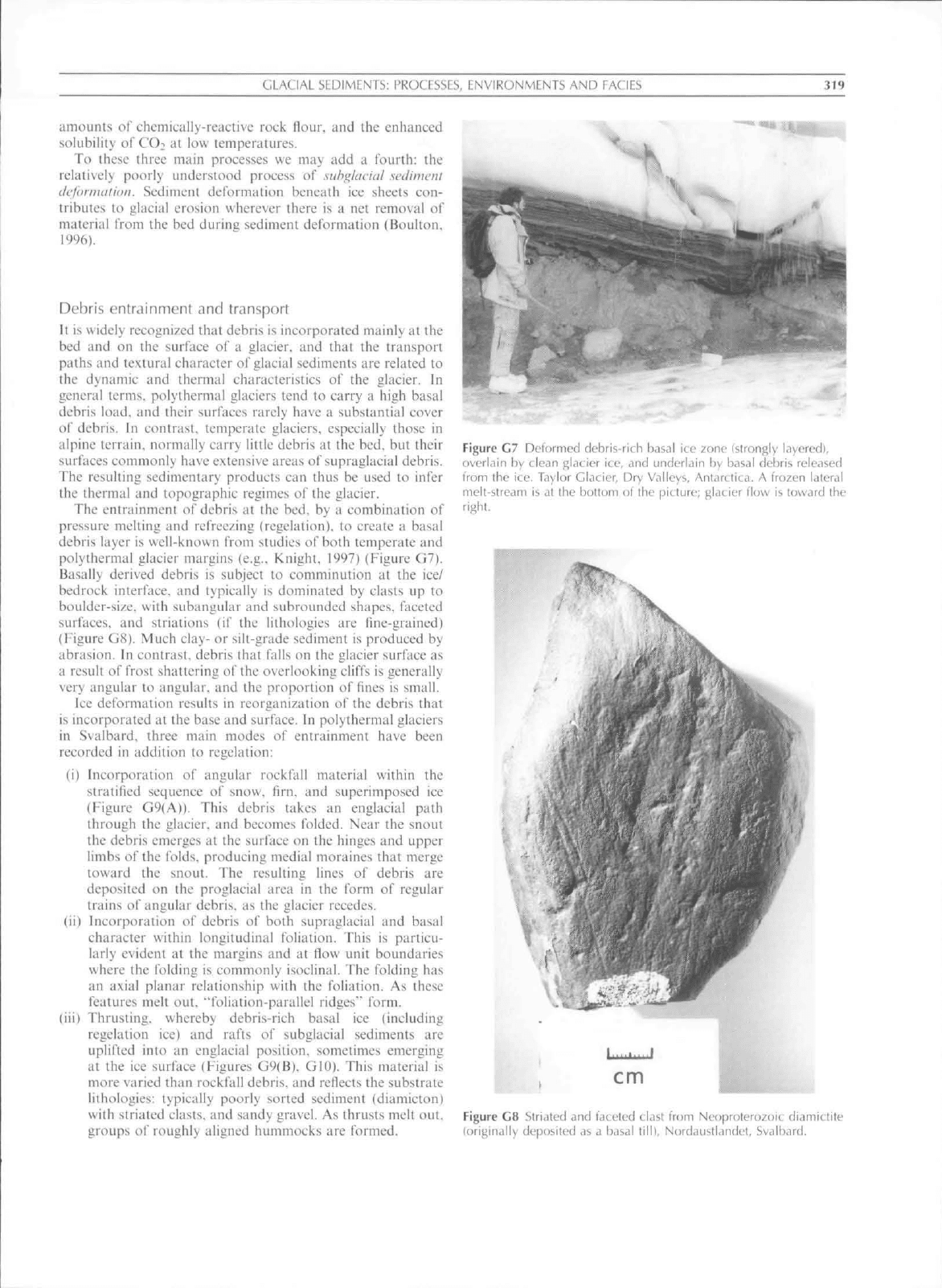

The entrainment of debris at the bed, by a combination of

pressure melting and refree/ing (regelation). to create a basal

debris layer is well-known from studies of both temperate and

polythermal glacier margins (e.g,. Knight. 1997) (Figure G7).

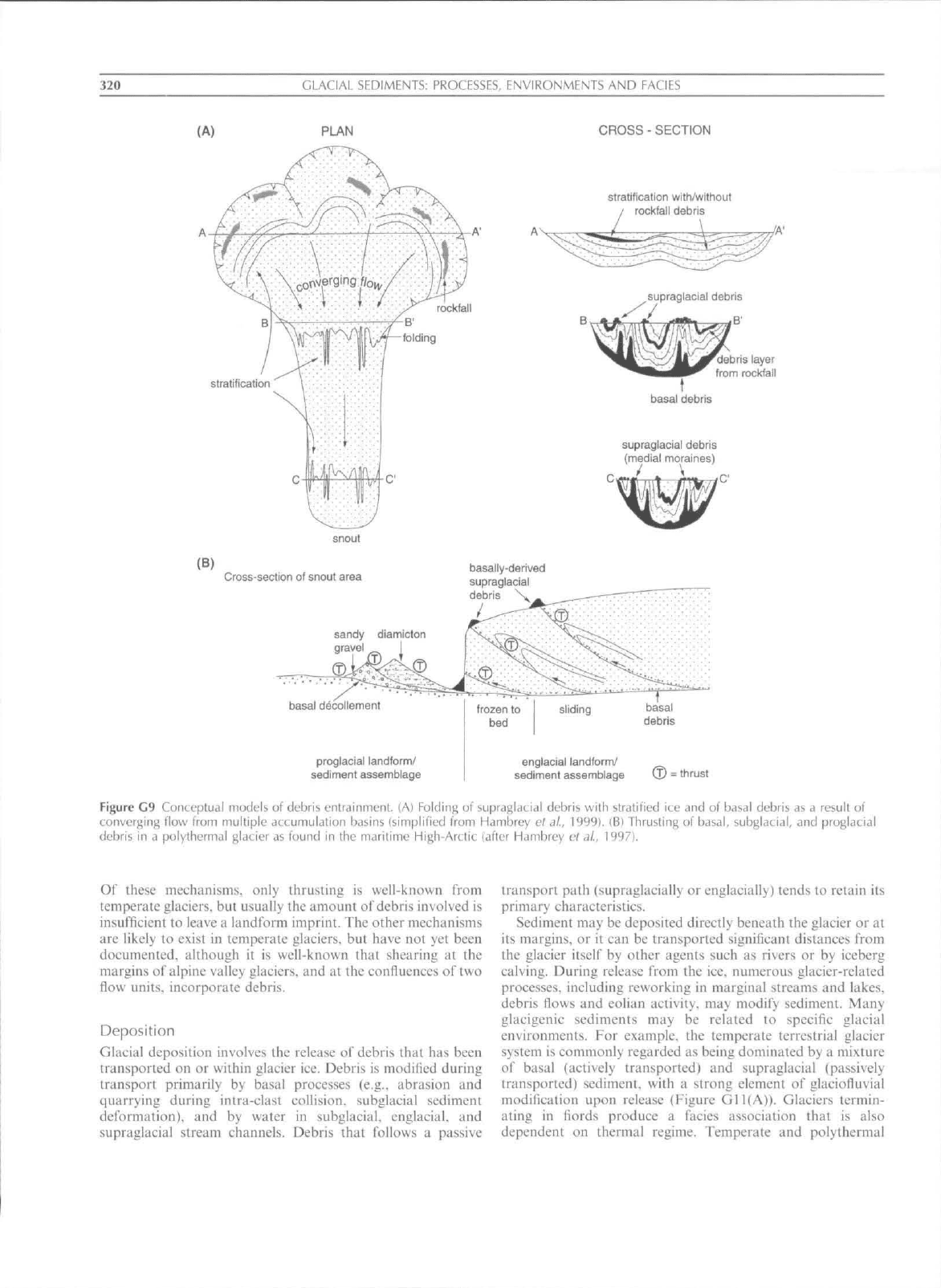

Basally derived debris is subject to comminution at the ice/

bedroek interfaee, and typieally is dominated by clasts up to

boulder-size, with subangular and subrounded shapes, faeeted

surfaces, and striations (if the lithologies are fine-grained)

(Figure G8). Much clay- or silt-grade sediment is produced by

abrasion. In contrast, debris that falls on the glacier surface as

a result of frost shattering of the overlooking cliffs is generally

very angular to angular, and the proportion of fmes is small.

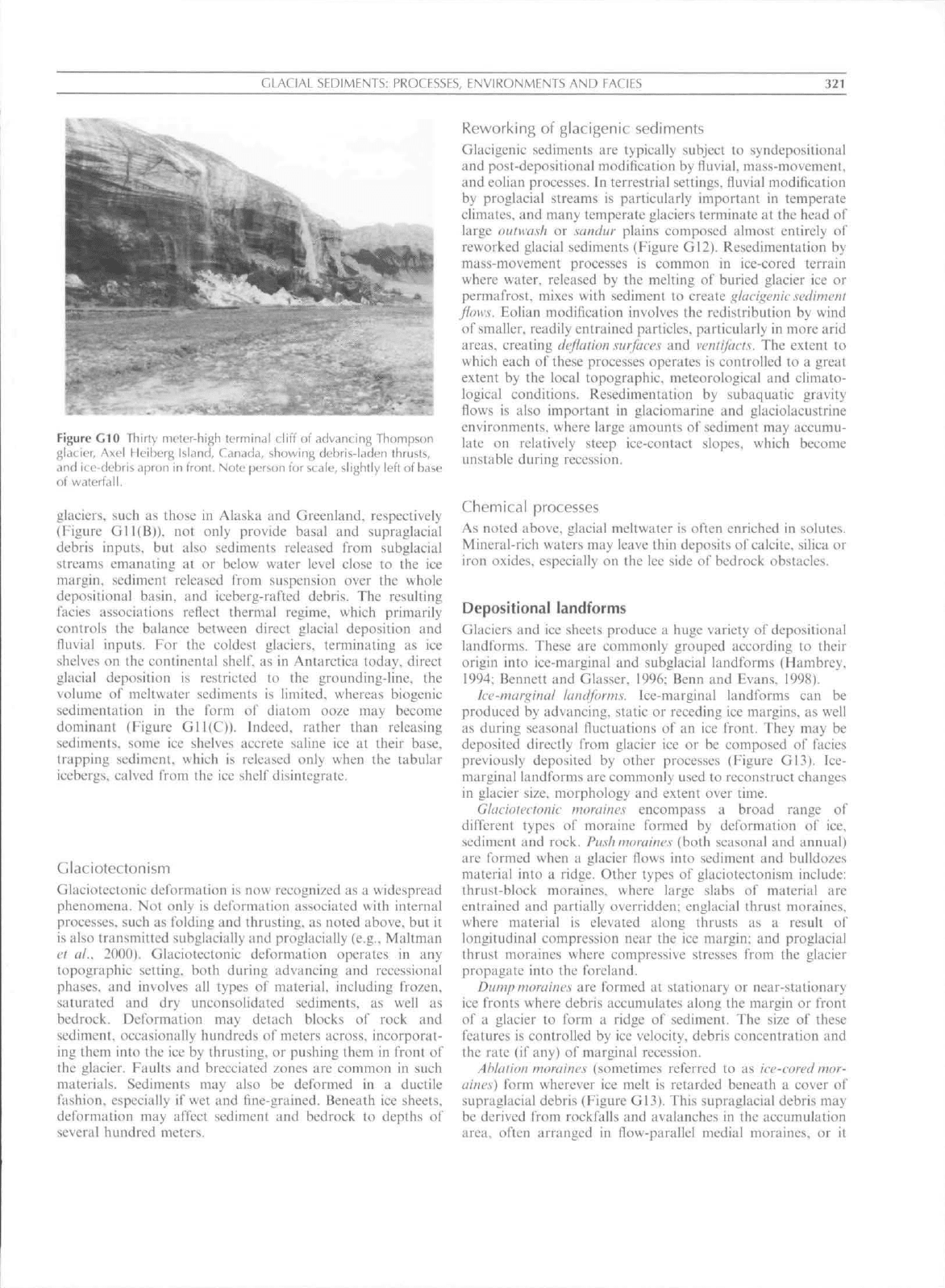

Ice deformation results in reorganization of the debris that

is incorporated at the base and surfaee. In polythermal glaciers

in Svalbard, three main modes of entrainment have been

recorded in addition to regelation:

(i) Incorporation of angular rockfall material within the

stratified sequence of snow, firn, and superimposed ice

(Figure G9(A)). This debris takes an englacial path

through the glacier, and becomes folded. Near the snout

the debris emerges at the surface on the hinges and upper

limbs of the folds, producing medial moraines that merge

toward the snout. The resulting lines of debris are

deposited on the proglacial area in the form of regular

trains of angular debris, as the glaeier recedes.

(ii) Incorporation of debris of both supraglacial and basal

character within longitudinal foliation. This is particu-

larly evident at the margins and at flow unit boundaries

where the folding is commonly isoclinal. The folding has

an axial planar relationship with the foliation. As these

features melt out. "foliation-parallel ridges"" form.

(iii) Thrusting, whereby debris-rich basal ice (including

regelation ice) and rafts of subglacial sediments are

uplifted into an englacial position, sometimes emerging

at the ice surface (Figures G9(B), GIO). This material is

more varied than rockfall debris, and reflects the substrate

lithologies: typically poorly sorted sediment (diamicton)

with striated clasts, and sandy gravel. As thrusts melt out,

groups

ci\'

roughly aligned hummocks are formed.

Figure C7 Deformed debris-rich basal ice zone (strongly layered),

overlain by clean glacier ice, and underlain by basal debris released

from the ice, Taylor Glacier, Dry Valleys, Antarctica. A frozen lateral

melt-stream is at the bottom of the picture; f^Jacier flow is lovvard the

right.

cm

Figure GS Striated and faceted clast from Neoproterozoic diamictite

{originally deposited as a basal

lilll,

Nordaustl.indet. Svalbard.

320 GLACIAL SEDIMENTS; PROCESSES, ENVIRONMFNTS AND FACIES

PUN

CROSS - SECTION

stratification witli/without

rockfall debris

supragiaciai debris

debris layer

from rockfall

basal debris

supragiacial debris

(medial moraines)

(B)

snout

Cross-section of snout area

basally-derived

supragiacial

debris \

sandy diamicton

gravel

i

basal d§collement

proglacial landform/

sediment assemblage

basal

debris

englacial landform/

sedinnent assemblage

(T) = thrust

Figure G9 Conceptual models of debris enlrtiinment. lA) Folding ot supraglatial debris wilh stratified ice and of basal debris as a result of

converging flow from multiple accumulation basins (simplified from FHambrey e(

nL,

1999). (B) Thrusting of basal, subglactal, and proglacial

debris in a polythermal glacier as found in the maritime High-Arttic (aficr Hambrey et

al.,

1997).

Of these mechanisms, only thrusting is well-known from

temperate glaciers, but usually the amount of debris involved is

insufficient to leave a landform imprint. The other mechanisms

are likely to exist in temperate glaciers, but have not yet been

documented, although it is well-known that shearing at the

margins of alpine valley glaciers, and at the confluenees of two

flow

units,

incorporate debris.

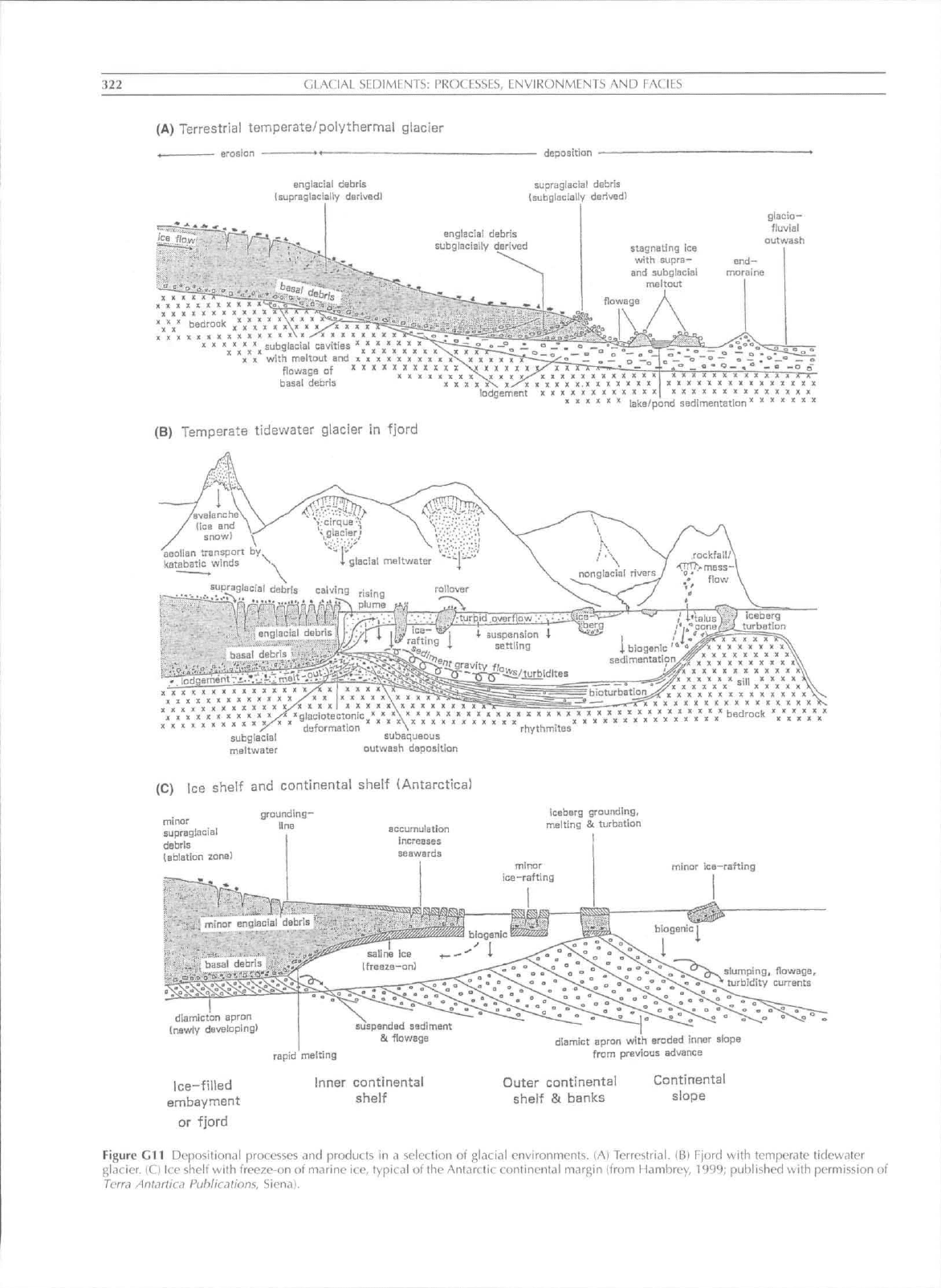

Deposition

Glacial deposition involves the release of debris that has been

transported on or within glacier ice. Debris is modified during

transport primarily by basal processes (e.g.. abrasion and

quarrying during intra-clast eollision. subglaeia! sediment

deformation), and by water in subglacial. englacial. and

supragiacial stream channels. Debris that follows a passive

transport path (supraglaeially or cnglacially) tends to retain its

primary characteristics.

Sediment may be deposited direetly beneath the glacier or at

its margins, or it can be transported significant distances from

the glacier itself by other agents such as rivers or by iceberg

calving. During release from the ice. numerous glacier-related

processes, including reworking in marginal streams and lakes,

debris flows and eolian activity, may modify sediment. Many

glaeigenic sediments may be related to specific glacial

environments. For example, the temperate terrestrial glacier

system is commonly regarded as being dotninated by a mixture

of basal (actively transported} and supragiacial (passively

transported) sediment, with a strong element of giaciofiuvia!

modification upon release (Figure Gll(A)), Glaciers termin-

ating in iiords produce a facies association that is also

dependent on thermal regime. Temperate and polythermal

GLACIAL SEDIMENTS; PKOCFSSES, FNVIRONMFNTS AND FACIES

321

Figure GIO Ihirty mfler-high terminal cliff of advancing Thompson

gkicier, Axel I leiberj; Isl.mrl, Canada, showing debris-laden thrusts,

and ictf-dt'bris ^ipron in

Ironl.

Note person for

scale,

slightly left of base

of waterfall.

glaciers, such as those in Alaska and Greenland, respectively

(Figure Gll(B)). not only provide basal and supraglacia!

debris inputs, but also sediments released from subglacial

streams emanating at or below water level close to the ice

margin, sediment released from suspension over the whole

depositional basin, and iceberg-rafted debris. The resulting

lacies associations relicct thermal regime, which primarily

controls the balance between direct glacial deposition and

lluvia! inputs. For the coldest glaciers, terminating as ice

shelves on the continental

shelf,

as in Antarctica today, direct

glacial deposition is restricted to the grounding-line, the

volume of meltwater sediments is limited, whereas biogenic

sedimentation in the form of diatom ooze may become

dominant (Figure Gll(C)). Indeed, rather than releasing

sediments, some ice shelves accrete saline ice at iheir base,

trapping sediment, which is released only when the tabular

icebergs, calved from the ice shelf disintegrate.

Glaciotectonism

Glaciotectonic deformation is now recognized as a widespread

phenomena. Not only is deformation associated with internal

processes, such as folding and thrusting, as noted above, but it

is also transmitted subglacially and proglacially (e.g.. Maltman

ct ai. 2000). Glaciotectonic deformation operates in any

topographic setting, both during advancing and recessional

phases, and involves all types of material, including frozen,

saturated and dry unconsolidated sediments, as well as

bedrock. Deformation may detach blocks of rock and

sediment, occasionally hundreds of meters across, incorporat-

ing them into the ice by thrusting, or pushing them in front of

the glacier. Faults and brecciated zones are common in such

materials. Sediments may also be deformed in a ductile

fashion, especially if wet and fine-grained. Beneath ice sheets,

deformation may affect sediment and bedrock to depths of

several hundred meters.

Reworking of glaeigenic sediments

Glaeigenic sediments are typically subject to syndepositional

and post-depositional modification by tluvial. mass-movement,

and eolian processes. In terrestrial settings, tluvial modification

by proglacial streams is particularly important in temperate

climates, and many temperate glaeiers terminate at the head of

large ouiwash or sandur plains composed almost entirely of

reworked glacial sediments (Figure GI2). Reseditnentation by

mass-movement processes is common in ice-cored terrain

where water, released by the melting o'i buried glacier ice or

permafrost, mixes with sediment to create

i^hicigenic

sediment

flaws. Eolian modification involves the redistribution by wind

of smaller, readily entrained particles, particularly in more arid

areas,

creating i/eflaiion surfaces and ventijiicis. The extent to

which each of these processes operates is controlled to a great

extent by the local topographic, meteorological and climato-

logicai conditions. Resedimentation by subaquatic gravity

flows is also important in glaciomarine and glaciolacustrine

environments, where large amounts of sediment may accumu-

late on relatively steep ice-contact slopes, which become

unstable during recession.

Chemical processes

As noted above, glacial meltwater is often enriched in solutes.

Mineral-rich waters may leave thin deposits of calcitc, silica or

iron oxides, especially on the Ice side of bedrock obstacles.

Depositional landforms

Glaciers and ice sheets produee a huge variety of depositional

landlbrms. These are commonly grouped according to their

origin into ice-marginal and subglacial landfonns (Hambrey.

1994:

Bennett and Glasser. 19%; Benn and Evans. 1998).

lee-marginal landforms. Ice-marginal landforms can be

produced by advancing, static or receding ice margins, as well

as during seasonal fiuctuations of an ice front. They may be

deposited directly from glacier ice or be composed o\' facies

previously deposited by other processes (Figure G13). Ice-

marginal landforms are commonly used to reconstruct changes

in glacier size, morphology and extent over time.

Glaciolcctonlc moraines encompass a broad range of

different types of moraine formed by deformation of ice,

sediment and rock. PushnnmiiiK's (both seasonal and annual)

are formed when a glacier flows into sediment and bulldozes

material into a ridge. Other types of glaciotectonism include:

thrust-block moraines, where large slabs of material are

entrained and partially overridden: englacial thrust moraines,

where material is elevated along thrusts as a result of

longitudinal compression near the ice margin; and proglacial

thrust moraines where comprcssive stresses from the glacier

propagate into the foreland.

Dump moraines are formed at stationary or near-stationary

ice fronts where debris accumulates along the margin or front

of a glacier to fortn a ridge of seditnent. The size of these

features is controlled by ice velocity, debris concentration and

the rate (if any) of marginal recession.

Ablation moraines (sometimes referred to as ice-cored mor-

aines) form wherever ice melt is retarded beneath a cover of

supragiacial debris (Figure G13). This supragiacial debris may

be derived from rockfalls and avalanches in the accumulation

area, often arranged in flow-parallel medial moraines, or it

322

GLACIAL SEDIMFNTS: PROCESSES, ENVIRONMENTS AND FACIFS

(A) Terrestrial temperate/polythermal glacier

deposition

englaclal debris

(supraglaclaliy derived)

supragiacial debris

Isubniaciaily derived)

englaciai debris

subglacially derived

stagnating

ice

with supra-

end—

and subglacial moraine

me

I

tout

glacio-

tluvial

out wash

^

" \\ X

X

="'^3'^'^'^'

"^'*'^^

X X X X X X X x\x X

X

X

with meltout

and

nxxxxxxxxx

flo\Aiaga

of

basal debris

(B) Temperate tidewater glacier

in

fjord

lodgement

lake/pond sedimentation

X

X X X X X X

X

X « S

X

« X I I <

XXKXXXXXXX

XXXIXXXXXX

subaqueous

outwash deposition

(C) Ice shelf and continental shelf (Antarctica)

iceberg grounding,

melting

5

turbation

slumping,

flowage

turbidity currents

dl.

(newly developing!

ice-filled

embay ment

or fjord

rapid melting

diamict apron with eroded inner slope

from previous advance

Inner continental

shelf

Outer continental

shelf

a

banks

Continental

slope

Figure

Gil

Depositional processes and products

in a

selection

of

glacial environments.

lA)

Terrestrial.

(B)

Fjord with temperate tidewater

glacier.

IC) ke

shelf with treeze-on

of

marine ice, typical

of

the Antarctic conlinentcal marj;in (from Hambrey, 1999; published with permission

of

Terra Antartic<i

Fuhlicjtions, Siena).

GLACIAL SFDIMKNTS: PROChSSFS, HNVIKONMENTS AND FACIES

323

Figure G12 lir,3irled river system emanating from debris-tovered Casement Glacier

(leitl,

southern Aldskj. Small pits on the outwash

.ire kettle holes iirising trom slow meltinj^ ot' buried ite blocks.

Figure C13 ttemar^innl l.incltorms, espet iaily altldtion niordirie, toniprising

.1

mixture' ot'

Vadret cUi Mortertitsch, SwitzerUnd.

itilly ^ind basdily derived deljris,

324

GLACIAL SEDIMENTS: PROCESSES, ENVIRONMENTS AND EACIES

may be composed of subglacial or englacial debris elevated to

the ice suriace by folding, thrusting or upward-directed flow

lines in the ablation urea. If the cover of insulating debris is

irregular, as is commonly the case, irregular ridges and

mounds of debris, often known as hummocky momiiu's, will

develop as ablation proceeds. Although initially large and with

a pronounced morphology, ablation moraines reduce drama-

tically in size as the ice-core melts and material is subject to

debris flowage.

Ouiwash funs and outwa.Hhplains (or saiuhir. plur: saiulur.

sing.) are formed as glacial meitwater emerges from the glacier

and sediment is deposited at or beyond the ice margin.

Outwash fans form at stationary ice margins where mellwater

is concentrated at a particular point for a length of time.

Outwash plains are much larger features, formed where

individual fans merge away from the glacier to create a

braided river facies association (Figure GI2). Characteristics

of the glaciofluvial environment are braided river channels

with rapidly migrating bars, terraees, frequent ehannel

avulsions and the formation of kellle holes where sediment is

deposited over buried ice.

Kame terraces are Ibrmed when sediment is deposited by

meltwater flowing laterally along an iee margin. Kumes are

more fragmentary features, formed in a similar manner, but

often in iee-walled tunnels and against steep valley sides.

Kcimi'-anii-keitle lopogiaphy is the term used to describe the

landform-sediment assemblage often found on glacier fore-

fields where there was formerly a high proportion of buried ice.

Suhglacidl

Iciniljorins

(sometimes referred to as suhglcicial

hedforms) are produced beneath actively flowing iee. They

provide information about former subglaeial conditions,

including ice-flow directions, thermal regime and paleohydrol-

ogy. The most common of these is a family of ice-molded

iandlbrms, all ol which are parallel to ice-flow. Fluies are low

(typically <3m), narrow (<3m). regularly spaced ridges that

are rarely continuous for less than lOOni. Megtifluics are taller

(>5ml. broader and longer (>l()()m) than flutes. Mcga-scale

lineaiiiiiis are much larger (tens of kilometers in length and

hundreds of meters in width) that are often only visible when

viewed on satellite imagery. Drumlins are typically smooth,

oval-shaped or elliptical hills composed of a variety of

glacigenic sediments. They are generally between

5

m and

5()ni high and lOm to 3,000m in length. Drumlins normally

have lengih-to-width ratios of less than 50. Their steeper, blunt

end often faces up-ice and they are often found in large groups

known as dnimlin

.swarms.

The origin of drumlins is unclear.

but they have been ascribed to subglacial deformation, to

lodgement, to the melt out of debris-rich basal ice and to

subglacial sheet floods.

Rihhedmoraines (also known as Rogen moraines) are large,

regularly and closely spaced moraine ridges eonsisting of

glaeigenie sediment. They are often curved or anastomosing,

but their general orientation is transverse to ice flow. They

often show drumlinoid elements or superimposed fluting.

Ribbed moraines may represent the fracturing of

a

pre-existing

subglacial till sheet at the transition from cold- to warm-based,

presumably during deglaciation.

Geometric ridge networks and crexasse-fill ridges are sub-

glacial landforms that arc not generally ice-molded. These

features, composed of subglacia! material, are low (l-3m

high) ridges that, when viewed in plan, show a distinct

geometric pattern. The traditional explanation for these

features is that they form by the squeezing of subglacial

material into basal crevasses or former subglacial ttinnels,

eommonly during surges. Alternatively, geometric-ridge net-

works also form beneath glaciers as a result of the intersection

of foliation-parallel ridges and englacial thrusts.

Eskers are glaciofluvial landforms created by the flow of

meltwater in subglaeial. englacial or supragiacial channels.

They are usually sinuous in plan and composed of sand and

gravel. Some eskers are single-crested, whilst others are

braided in plan. Concertina eskers are deformed eskers, created

by compression beneath overriding ice.

Bathymetric forms resulting from glacial processes

Erosional forms

Various erosional phenomena, mainly associated with

grounded ice or subglacial meltwater are found in marine

settings. The larger scale forms arc tilled by sediment and may

be recognizable in seismic profiles (e.g., Anderson. 1999).

Suhnuirine troughs are found on continental shelves, and are

genetically equivalent to fiords and other glacial troughs, but

are generally much broader. The largest occur in Antarctica

where they attain dimensions of over 400 km in length, 200 km

in width and 1.100 m in depth. They are formed by ice streams

and, where two streams merge, an

ice-.srream

boundary

ridge

is

formed. Steep-sided channels a few kilometers wide, carved

out by subglacial meltwater and subsequently tilled by

sediment, are known as tunnel

valleys.

These are well-known

from the NW European continental shelf around Britain, the

Scotian Shelf off Canada, and in Antarctica. Icebergs can also

cause eonsiderable erosion as they become grounded on the

seafloor. Large tabular bergs ean seour the bed of the sea for

several tens of kilometers, leaving impressions up to lOOm

wide and several meters deep. Slope valleys are groups of

gullies forming a dendritic pattern, and develop just beyond

the ice margin, on the continental slope, as a result of erosion

by sediment gravity flows emanating from sediment that

accumulated at the ice margin. On continental shelf areas.

where the iee repeatedly becomes grounded, and then releases

a large amount of rain-out sediment, alternations of diamicton

and boulder pavements may be observed. The pavements build

up by accretion of boulders around an obstaele, by subglacial

erosion, or as a lag deposit from winnowing by bottom

currents.

Depositional forms

The morphology and sediment composition of subaquatic

features, particularly in fjords and on continental shelves are

less well-known than their terrestrial counterparts, but major

strides have been made in identifying such features in the last

two decades. As on land, depositional assemblages reflect the

interaction of a wide range of processes.

Ice-contact features form when a glacier terminus remains

quasi-stationary in water, particularly in tiords (Powell and

Alley. 1997) (Figure G14). Morainal hanks form by a

combination of lodgement, meltout, dumping, push and

squeeze processes, combined with glaciofluvial discharge:

poorly sorted deposits arc typical of such features. Ground-

ing-line fans extend from a subglacial tunnel that discharges

meltwater and sediment into the sea. and are typically

composed of sand and gravel. Developing out of grounding-

line tans are ice-eontact deltas that form when the terminus