Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

188

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM

CHAPTER 27

Stephen J. Wolf, MD

1. What is Virchow triad of thromboembolism?

Venous stasis, vascular trauma, and hypercoagulable state.

2. What two diseases represent the continuum of venous thromboembolism

(VTE)?

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

3. What percentage of patients diagnosed with DVTs have concomitant PE

when studied?

Fifty percent. Additionally, a similar percentage of patients with a diagnosed PE will have

a concomitant DVT when studied.

KEY POINTS: MAJOR RISK FACTORS CARRYING A RELATIVE

RISK OF 5 to 20 FOR VTE

1. Recent surgery (< 4 weeks)

2. Immobilization (equivalent to bed rest > 3 days)

3. Pregnancy (third . second . first trimester)

4. Postpartum (for up to 42 days)

5. Malignancy (treatment active, within 6 months, or palliative)

6. History of VTE

4. List the minor risk factors for VTE.

n

Cardiovascular disease (i.e., heart failure, hypertension, or congenital heart disease)

n

Indwelling vascular access

n

Estrogen use (hormone replacement or oral contraceptives)

n

Obesity

n

Neurologic disease (i.e., cerebrovascular accident [CVA], paresis)

n

Inflammatory bowel disease (i.e., Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis)

n

Tobacco

n

Advanced age

n

Hypercoagulable states (i.e., factor V Leyden thrombophilia, prothrombin mutation,

circulating lupus anticoagulant, antithrombin III deficiency, and protein C or

S deficiency)

5. What is the relative risk for VTE in a patient with a minor risk factor?

Two to four times that of a patient without a minor risk factor.

Chapter 27 VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM 189

6. Are there any signs or symptoms of PE that are diagnostic?

No. Although the common clinical signs and symptoms of shortness of breath, chest pain,

tachypnea, and tachycardia occur in upward of 97% of patients diagnosed with PE, they are

nonspecific. Patient presentations can range from mild shortness of breath to cardiovascular

collapse.

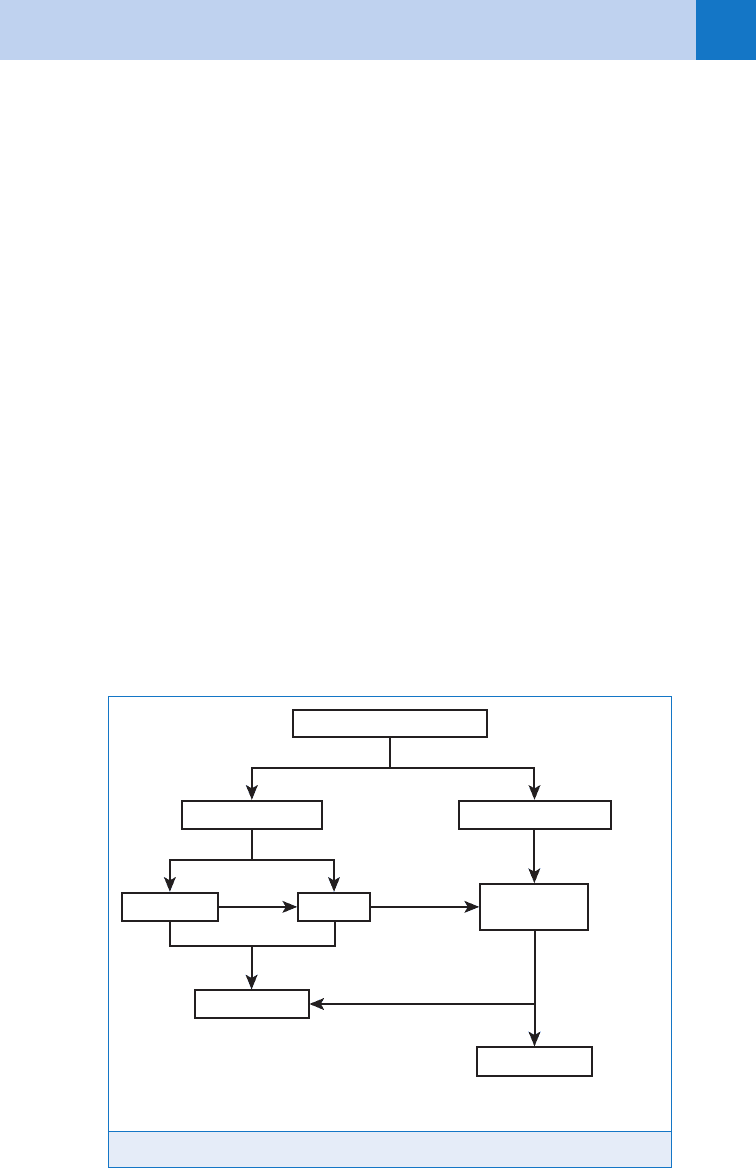

7. Why is a clinician’s pretest probability for VTE so important?

Because no diagnostic test available for the evaluation of VTE is absolute (with a perfect

sensitivity and specificity), the results of any given test must be considered in combination

with the pretest probability to yield a posttest likelihood of disease. Thus, the pretest

probability should be used to determine when to initiate a patient work-up and how to

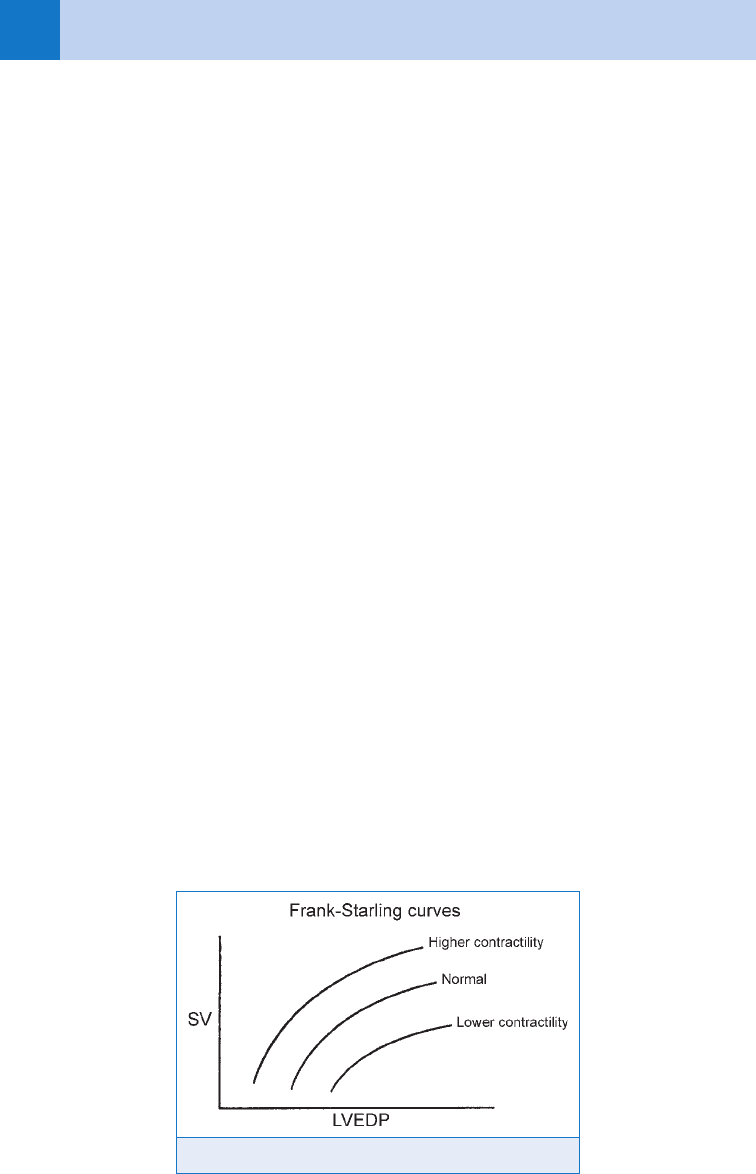

interpret the results of any test. See Fig. 27-1.

8. When determining pretest probability for DVT, what are the Wells Criteria?

n

Malignancy (11.0 point)

n

Paralysis/cast (11.0 point)

n

Recent immobilization or surgery (11.0 point)

n

Tenderness along deep veins (11.0 point)

n

Swelling of entire leg (11.0 point)

n

3-cm difference in calf circumference (11.0 point)

n

Pitting edema (11.0 point)

n

Collateral superficial veins (11.0 point)

n

Alternative diagnosis more likely than DVT (-2.0 points)

9. Once I have calculated the total Wells score for DVT, how do I interpret it?

The incidences of DVT based on the Wells Criteria for DVT follow:

n

Low pretest probability (,2 points): 3% incidence

n

Moderate pretest probability (2–6 points): 17% incidence

n

High pretest probability (.6 points): 75% incidence

Figure 27-1. Clinical suspicion for VTE.

Very low/low PTP

PERC rule*

D-dimer

Clinical suspicion for VTE

VTE excluded

(+)

(+)

(+)

(−)

(−)**

Moderate/high PTP

Radiographic

imaging

Treat for VTE

*For patients with suspicion of PE

**Consider alternative radiographic imaging or D-dimer to improve sensitivity

Chapter 27 VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM190

10. What is the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) rule for pulmonary

embolism?

PERC is a clinical decision rule that can be used to identify patients who do not require a laboratory

or radiograph work-up to exclude the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. The criteria include:

n

Age ,50 years

n

Heart rate ,100 beats per minute

n

Initial room air SaO

2

.94% at sea level

n

No clinical signs suggesting DVT/PE

n

No hemoptysis

n

No recent surgery or trauma

n

No history of VTE

n

No oral hormone use

11. How do I use the PERC rule?

In patients with a low gestalt clinical suspicion for PE, if all criteria are met, the patient has a

less than 2% risk of PE, and further work-up is not indicated. Patients with clinical suspicion

who do not meet all criteria may require further evaluation.

12. When determining pretest probability for PE, what are the Wells Criteria?

n

Signs/symptoms of DVT (13 points)

n

No alterative diagnosis more likely than PE (13 points)

n

Heart rate .100 beats per minute (11.5 points)

n

Recent immobilization or surgery (11.5 points)

n

History of previous VTE (11.5 points)

n

Hemoptysis (11.0 point)

n

Malignancy (11.0 point)

13. Once I have calculated the total Wells score for PE, how do I interpret it?

The incidences of PE based on the Wells Criteria for PE follow:

n

Low pretest probability (,2 points): 4% incidence

n

Moderate pretest probability (2–6 points): 21% incidence

n

High pretest probability (.6 points): 67% incidence

14. What is a D-dimer test? How is it used?

D-Dimer, a degradation product of cross-linked fibronectin, is found in increased levels of the

circulation of patients with acute VTE. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), rapid

ELISA, turbidimetric, and whole-blood agglutination D-dimer assay are useful to exclude

thromboembolic disease in patients with low pretest probability for VTE. Traditional latex

agglutination tests cannot be used in these algorithms because of poor negative predictive

values. Although useful in ruling out venothromboembolic disease in select populations,

owing to a lack of specificity, D-dimer has not proved useful at ruling in the diagnosis.

15. Which patients can have VTE excluded, based on a negative D-dimer?

Low to low-moderate pretest probability patients only. You would miss the diagnosis

anywhere from 5% to 20% (depending on the type of assay) of the time if you used a negative

D-dimer to rule out VTE in a patient with a moderate to high pretest probability (.40%).

16. What are some clinical situations that cause a false-positive D-dimer, lending

to a decreased specificity?

Sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), aortic dissection, pregnancy, recent

surgery, and severe trauma.

17. What are some clinical situations that might cause a false-negative D-dimer?

n

Subacute thrombosis (.7 days)

n

Recent anticoagulation

Chapter 27 VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM 191

18. What noninvasive imaging methods are available for the diagnosis of DVT?

n

Duplex ultrasound: The sensitivity and specificity are operator dependent and related to

patient symptomatology, but this test can detect more than 95% of acute symptomatic

proximal DVTs. It should be noted that its specificity for acute thrombosis decreases in the

settings of chronic or recurrent VTE.

n

Radio fibrinogen leg scanning: Good for detecting distal clots, including clots in the calf,

popliteal ligament, and distal thigh vein, but relatively poor for more proximal clots.

n

Impedance plethysmography: The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity depend on the

technical expertise of the person doing the study, but in many centers this test detects

more than 95% of acute proximal lower extremity DVT.

n

Spiral computed tomography (CT) venography. Although rarely used and not extensively

studied, reports show promise for this modality, with a sensitivity and specificity

comparable to ultrasound.

n

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) venography. Can be useful, particularly for patients

with inconclusive ultrasound studies or a contraindication to radiation or contrast dye (i.e.,

pregnant patients). It has proved accurate for both lower extremity and pelvic DVT.

19. Can a single duplex ultrasound exclude DVT in isolation?

No. In patients with a moderate to high pretest probability for DVT, a negative D-dimer or a

repeat duplex ultrasound in 5 to 7 days is indicated to definitively exclude the diagnosis.

20. Are there classic chest X-ray (CXR) findings in patients with PE?

No. The chest radiograph may be normal in up to 30%. Subtle abnormalities such as focal

atelectasis, slight elevation of a hemidiaphragm, or focal hyperlucency of the lung

parenchyma, may be present. Specifically, local oligemia of vascular markings (Westermark’s

sign) or a plural-based wedge-shaped infiltrate suggestive of pulmonary infarct (Hampton’s

hump) is relatively uncommon.

21. Are there classic electrocardiogram (ECG) findings in patients with PE?

No. Normal or near-normal ECGs with sinus tachycardia or nonspecific ST-T wave changes

may be seen up to 30%. The findings classically associated with PE (i.e., S1, Q3, T3 pattern or

a new right bundle-branch block) occur in less than 15% of patients and occur with the same

frequency in patient work-up whether or not they are diagnosed with PE.

22. What imaging studies can be used to evaluate PE?

n

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) scan. CTA is rapid and generally the test of

choice. It is highly sensitive in diagnosing central or segmental emboli and other

intrathoracic pathology, however not as sensitive in ruling out subsegmental clots.

Outcomes data using newer generation multirow detector CTAs are showing higher

sensitivities. Diagnostic accuracy can be improved by performing CTA with a CT

venography (CTV), if indicated.

n

Ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan. Traditionally, a normal V/Q scan has been used to

essentially rule out a diagnosis of PE with a posttest probability of disease of ,4%.

Likewise, a high-probability scan is considered to rule in the diagnosis. Unfortunately,

upward of 60% of V/Q scans are read as nondiagnostic (low or intermediate probability),

particularly if the chest radiograph is abnormal or the patient has underlying

cardiopulmonary disease. A nondiagnostic scan should be followed up with further

diagnostic work-up. Limitations of the V/Q scan include tech support, availability, and

interpretation variability.

n

Pulmonary angiogram. This test has been the traditional gold standard for the diagnosis,

even though its inter-rater agreement on interpretation has been reported to be as low as

65%. Limitations include contraindications to contrast dye injection, interventional

radiology support, interpretation variability, and the need for expertise.

n

Magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA). Limited studies have shown MRA has sensitivities

and specificities comparable to standard pulmonary angiogram. Although often not

Chapter 27 VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM192

immediately available, MRA is a useful modality when contraindications to conventional

studies, such as contrast allergies or pregnancy, exist.

23. What are the relative contraindications to CTA for PE?

n

Contrast dye allergy

n

Renal insufficiency

n

Inability to lie flat

n

Severe claustrophobia

n

Morbid obesity exceeding the CT scanner’s weight limit

24. What are the diagnostic test options for PE with the pregnant patient?

Although less specific in pregnancy, a D-dimer test can still be sensitive for excluding the

diagnosis in low pretest probability patients. For patients requiring diagnostic imaging, it is

important to recognize that both CTA and the V/Q scan carry a radiation risk to the fetus that

should be discussed with the patient. Recently, CTA (without concomitant CTV) has been

shown to confer lower fetal radiation doses than the V/Q scan. CTV should be avoided due

to the high pelvic radiation doses. When available, MRI is a diagnostic option that carries

minimal radiation risk; however, it requires cardiac and respiratory gating in addition to

significantly more time. Finally, the ultrasonographic identification of DVT in pregnant patients

with respiratory complaint can obliviate the need for thoracic testing.

25. What happens if the diagnosis of PE is missed?

PE is listed as one of the most common causes of death in the United States, and yet only

about 25% of cases are diagnosed. Of the undiagnosed 75%, a small number die within

1 hour of presentation, so it is unlikely that diagnosis and intervention could improve outcome

in that group. In the rest, however, the mortality from untreated PE is approximately 30%.

26. What is a massive PE?

A massive PE can be either anatomically defined as the occlusion of greater than 50% of the

pulmonary vasculature or physiologically defined as an embolus that is complicated by severe

cardiopulmonary distress. These two definitions are not synonymous because a normal

individual can lose 50% of pulmonary circulation without significant hemodynamic

compromise, whereas a patient with significant underlying cardiopulmonary disease could

suffer major hemodynamic compromise with a much smaller clot.

27. What is the treatment for VTE?

Anticoagulation should be started in the ED. Studies suggest that patients with proximal DVTs

and temporary risk factors can be anticoagulated with heparin (80 mg/kg loading dose

followed by 18 mg/kg/hour infusion) followed by Coumadin for 3 months, whereas patients

with calf DVTs need to be treated for only 6 weeks. Patients with permanent risk factors

potentially need lifelong treatment but should be anticoagulated for at least 6 months.

28. What is the role of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) in the treatment

of VTE?

LMWH is at least as effective as heparin for the treatment of DVT and probably should be

considered the treatment of choice based on efficacy, low side effect profile, and cost-

effectiveness. Outpatient management of DVT with LMWH is commonplace and has proved

safe and effective. Subgroup analysis indicates that LMWH probably will be adopted for the

treatment of PE as well, although further conclusive studies are needed.

29. Under what conditions can an inferior vena caval filter be considered in the

treatment of VTE?

n

Contraindication to anticoagulation

n

Recurrent VTE despite adequate anticoagulation

Chapter 27 VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM 193

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee Pulmonary Embolism Guideline Development Group:

British Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of suspected acute pulmonary embolism. Thorax

58:470–484, 2003.

2. Chan TC, Vilke GM, Pollack M, et al: Electrocardiographic manifestations: pulmonary embolism. J Emerg Med

21:263–270, 2001.

3. Craig F: Venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. In Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, editors:

Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice, ed 5, St. Louis, 1998, Mosby, pp 1770–1805.

4. Hann CL, Streiff MB: The role of vena caval filters in the management of venous thromboembolism. Blood

Rev 19:179–202, 2005.

5. Kline JA, Courtney DM, Kabrhel C, et al: Prospective multicenter evaluation of the pulmonary embolism rule-

out criteria. J Thromb Haemost 6: 772–780, 2008.

6. PIOPED Investigators: Value of the ventilation-perfusion scan in acute pulmonary embolism. JAMA 263:

2794–2795, 1990.

7. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Bormanis J, et al: Value of assessment of pretest probability of deep-vein thrombosis

in clinical management. Lancet 350:1795–1798, 1997.

8. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al: Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic

imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency

department by using a simple clinical model and D-dimer. Ann Intern Med 135:98–107, 2001.

9. Winer-Muram HT, Boone JM, Brown HL, et al: Pulmonary embolism in pregnant patients: fetal radiation dose

with helical CT. Radiology 224:487–492, 2002.

10. Wolfe TR, Hartsell SC: Pulmonary embolism: making sense of the diagnostic evaluation. Ann Emerg Med

37:504–514, 2001.

195

CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE AND

ACUTE PULMONARY EDEMA

CHAPTER 28

Jeffrey Sankoff, MD, FACEP, FRCP(C)

VI. CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

1. What is congestive heart failure (CHF)?

Cardiac dysfunction that leads to an inability of the heart to work as a pump to meet the

circulatory demands of the patient. As a result, pulmonary congestion occurs, and when

the problem is severe enough, pulmonary edema results.

2. What causes CHF?

CHF results from any of four types of processes:

n

Restrictive (hemochromatosis, pericardial disease)

n

Ischemic (myocardial infarction)

n

Congestive (volume overload of the ventricle from valvular insufficiencies)

n

Hypertrophic (longstanding hypertension or valvular stenoses)

3. Describe the symptoms of CHF.

Common symptoms are dyspnea (the subjective feeling of difficulty with breathing) and

fatigue. Early in the course of CHF, the patient reports exertional dyspnea; the heart is

able to supply enough cardiac output for sedentary activities but does not have the

reserve to increase cardiac output during exercise. As heart failure worsens, even

minimal activity may be difficult. Patients also report orthopnea (dyspnea relieved by

assuming an erect posture), paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (sudden onset of dyspnea at

night), and nocturia.

4. What causes these symptoms?

When the patient with CHF assumes the supine posture, venous return from the abdomen

and lower extremities is improved, increasing right ventricular cardiac output to the

pulmonary vasculature. Because of limitations on the ability of the left ventricle to increase

output increased pulmonary hydrostatic pressure results. The patient has difficulty lying

flat and sleeps with several pillows or sits in a chair to relieve these symptoms.

Redistribution of fluid may also lead to increased urine output and nocturia. In severe CHF,

volume redistribution may be sufficient to lead to acute pulmonary edema.

5. Name the four main determinants of cardiac function in CHF.

Cardiac output (CO) 5 stroke volume (SV) 3 heart rate (HR)

KEY POINTS: CARDINAL SYMPTOMS OF CHF

1. Exertional dyspnea

2. Fatigue

3. Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

4. Orthopnea

Chapter 28 CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE AND ACUTE PULMONARY EDEMA196

SV is determined by:

n

Preload

n

Afterload

n

Myocardial contractility

6. What is preload?

Within limits, the amount of work cardiac muscle can do is related to the length of the muscle

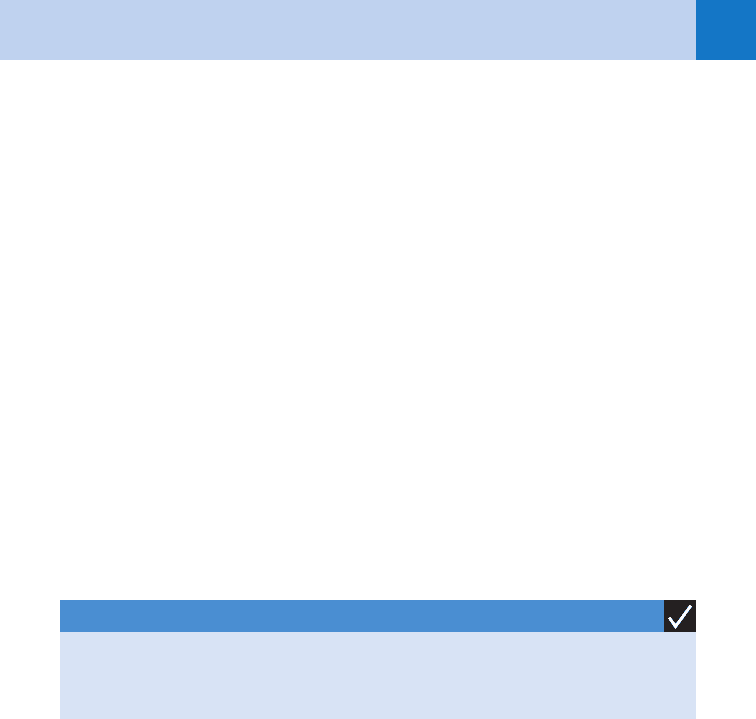

at the beginning of its contraction. This relationship is shown graphically by the Frank-

Starling curve, in which ventricular end-diastolic volume (VEDV) represents muscle length

and the SV represents cardiac work. (It is easier to measure pressure than volume, so we

graph ventricular end-diastolic pressure [VEDP] versus SV.) Thus, preload is measured as

VEDP. As VEDP increases, SV increases. At higher VEDP, the increase in SV is less for a given

increase in VEDP.

7. What are the effects of decreased contractility?

From Figure 28-1, it can be seen that the heart can function on different Frank-Starling curves,

depending on the contractility. A heart with better contractility will produce more CO than a heart

with poorer contractility for the same preload. CHF results when the right and left ventricles

begin to respond differently to similar preloads (i.e., operate on different Frank-Starling curves).

If the right ventricular output for a given preload is better than the left for the same preload, the

left ventricle cannot keep pace with the right and the difference remains in the pulmonary

vasculature increasing hydrostatic forces and eventually leading to pulmonary edema.

8. What about afterload?

Afterload refers to the pressure work the ventricle must do. The important components here

are ventricular wall tension and systemic vascular resistance (SVR). As SVR increases

(hypertension), the left ventricle must generate more force to push blood forward against this

resistance. The result is an increase in ventricular wall tension that may compromise blood flow

to myocytes. The response of the myocardium to chronic hypertension is to increase in size.

This hypertrophy eventually compromises the ability of the heart to produce adequate CO.

9. What about HR?

Low HR may cause low CO even in normal hearts because CO 5 SV 3 HR. But at excessively

high HRs, there may be insufficient time to fill the ventricle during diastole, leading to

decreased left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) and SV, so CO may become

compromised despite the tachycardia.

10. How does this physiology relate to treatment?

The goal of treatment of CHF is to improve CO. This can be accomplished by modifying

each of these parameters. Diuretics, dietary salt, and water restriction decrease preload and

Figure 28-1. The Frank-Starling curve.

Chapter 28 CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE AND ACUTE PULMONARY EDEMA 197

improve volume work. Inotropic agents such as digoxin improve contractility. Vasodilators

are helpful in reducing afterload and the pressure work required of the heart.

11. Describe the role of B-type natriuretic peptides (BNP) in CHF.

Natriuretic peptides are hormones produced by the heart in response to increased wall stress

and are secreted into the circulation as a marker of failure. BNP is an independent predictor

of increased LVEDP, and levels correlate with symptoms and severity of disease. It has been

suggested as a screening tool for the diagnosis of CHF in the ED, although its utility is limited.

12. How do I interpret BNP levels?

n

,100 pg/mL unlikely to be CHF

n

100–500 pg/mL may be CHF

n

500 pg/mL most consistent with CHF (There is difficulty interpreting elevated BNP when

patient has known severe CHF.)

13. How do patients with CHF present to the ED?

Patients with CHF present to the ED in one of two ways:

n

As a subacute gradual worsening with slow progression of symptoms and signs

n

Or as an acute, dramatic change from baseline with acute flash pulmonary edema

With respect to the first presentation, these patients tend to have evidence of worsening

fluid overload, with elevated jugular venous distension and peripheral edema. They may have

associated pulmonary edema as well, but it is usually mild to moderate with no respiratory

distress. The second presentation is seen in patients who are generally euvolemic but have

profound pulmonary edema as their main symptom.

KEY POINTS: ED PRESENTATIONS OF CHF

1. Subacute, fluid overloaded

2. Acute flash pulmonary edema, euvolemic

14. Discuss acute pulmonary edema.

The most dramatic presentation of CHF is acute pulmonary edema. To understand pulmonary

edema, we must return to the physiologist Starling, who described the interaction of forces at

the capillary membrane that lead to flow of fluid from capillaries to the interstitium. Simply

put, there is a balance between hydrostatic pressure and osmotic pressure. Under normal

circumstances, this leads to a small net movement of fluid from the capillaries into the lung

interstitium. This fluid is carried away by lymphatics. In CHF, the left ventricular CO changes

suddenly while the right ventricle remains unchanged. As a result there is a sudden increase

in pulmonary vascular volume and the capillary hydrostatic pressure increases to the point

that the lymphatics no longer can handle the fluid. This then leads to interstitial edema, and

subsequently to alveolar edema.

15. How do patients with acute pulmonary edema usually present?

Patients develop acute shortness of breath and generally are fighting for air. These patients

sit upright to decrease venous return (preload); they cough up frothy, red-tinged sputum.

Auscultation of the lungs reveals wet rales throughout and sometimes wheezes (owing to

bronchospasm, or cardiogenic asthma). This presentation is a true emergency and requires

immediate aggressive therapy. Because of the stress response that this causes, patients have

a large catecholamine release and are almost always very hypertensive. In these patients,

hypertension is the response to and not the cause of the acute CHF, although left unchecked,

the hypertension will result in an overall worsening.