Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter 23 TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK AND CEREBROVASCULAR ACCIDENT158

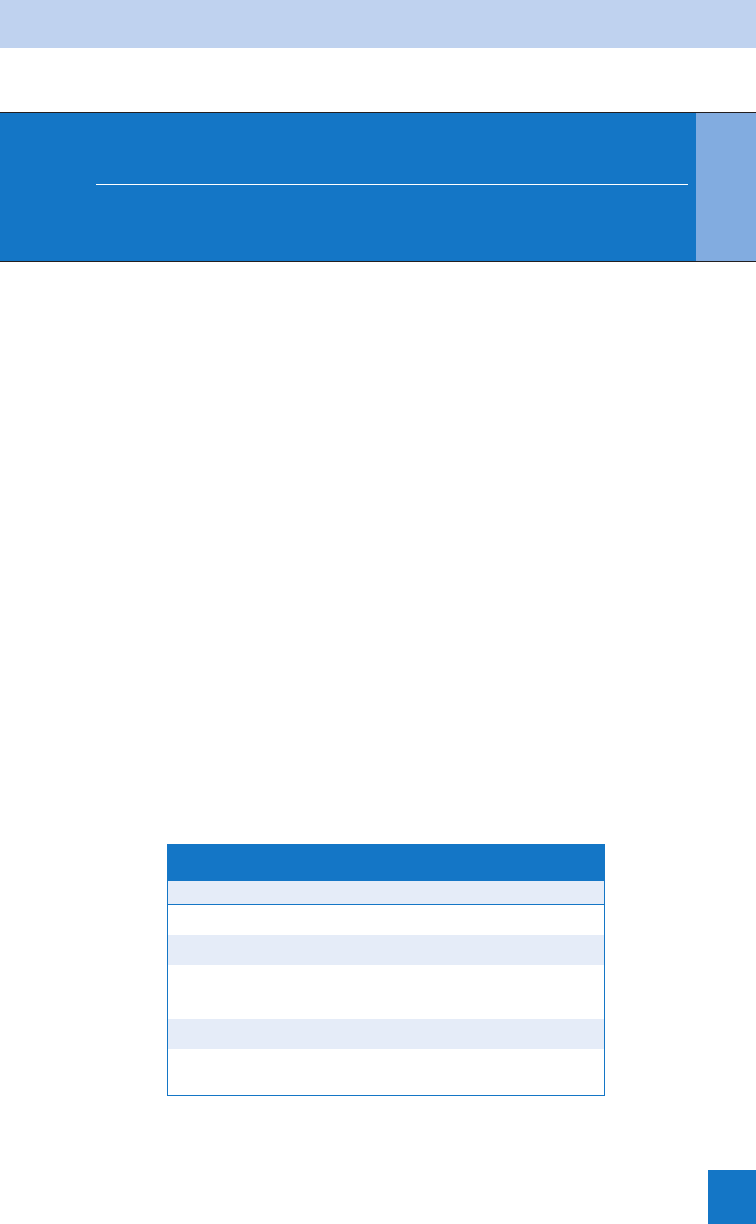

20. What are the indications and contraindications for tPA?

Note that the criteria for ECASS III are more restrictive than for NINDS (Table 23-2). In addition,

AHA/ASA guidelines have been modified slightly from original trial criteria, thus established

institutional protocols should be developed.

21. Why is there controversy with tPA for acute ischemic stroke?

There remains controversy partly stemming from the potential for serious harm (i.e., ICH) that

can occur with tPA therapy. Critics argue that the original NINDS trial inappropriately distorted

the measured benefit by recruiting half of subjects within 0 to 90 minutes from symptom

onset because, in typical ED practice, the majority of patients will not fall into this time

window. Additionally, there is concern that widespread community usage will have different

results, although part of this difference likely results from protocol violations, an argument

supporting rigorous adherence to stroke protocol.

22. What are the key points in getting informed consent?

Informed consent requirements will vary depending on institutional protocols. At minimum, the

risks, benefits, and alternatives should be explained and confirmed to be understood by the

patient or the patient’s surrogate decision maker. The alternative is not giving tPA. In community

observational studies, the reported range of symptomatic ICH within 3 hours is 3.3% to 7.3%.

There are no community data yet for the 3- to 4.5-hour window. Furthermore, improved

functional outcome can occur spontaneously (NINDS 26% in placebo arm, ECASS III 45%).

23. What must I do after giving tPA?

Current guidelines recommend admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) for at least 24 hours

with frequent neurologic checks. Avoid other antithrombotic agents for 24 hours (i.e., heparin,

warfarin, aspirin, ticlopidine, and clopidogrel). Maintain BP below 180/105 for the first

24 hours. Invasive procedures (i.e., venipuncture, catheter placement, and nasogastric

tube) should be avoided for 24 hours.

24. How should I manage ICH?

In the setting of tPA, consider new ICH if a sudden neurological decline, new headache,

nausea or vomiting, and sudden BP rise within 24 hours. If suspected, immediately stop the

tPA, perform stat head CT, and send labs (i.e., type and cross-match, prothrombin time [PT],

partial thromboplastin time [PTT], platelets, fibrinogen). If ICH is confirmed, consider giving:

n

10 units cryoprecipitate

n

6 to 8 units of platelets (or one single donor unit)

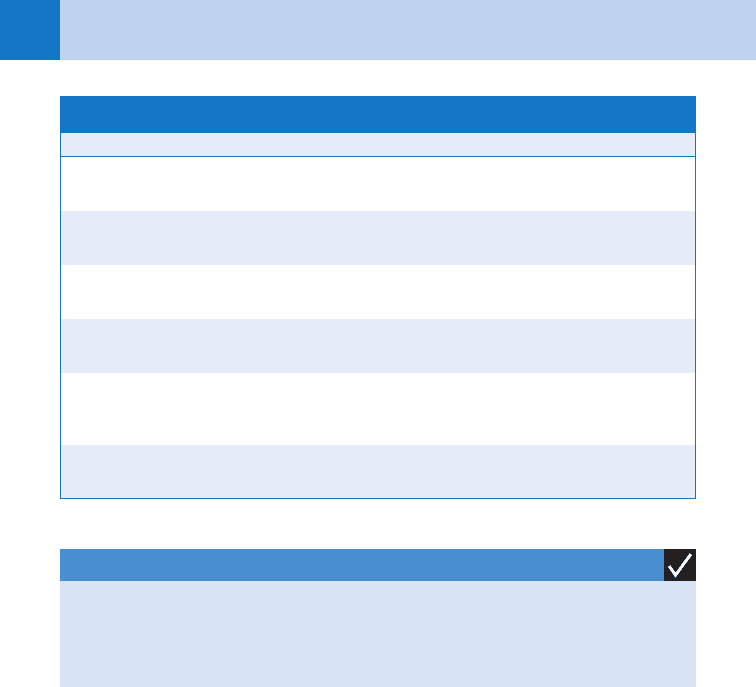

KEY POINTS: SUCCESSFUL ADMINISTRATI ON O F TPA

1. Adhere to stroke alert protocol.

2. Be exact about the time of onset; document it.

3. Immediately consult with neurologist.

4. Expedite the head CT and final radiology reading.

5. Send labs early (i.e., fingerstick glucose, complete blood count [CBC], PT/PTT, chemistry,

and troponin).

6. Mix the tPA early; calculate your dosage (0.9 mg/kg actual body weight; max 90 mg).

7. Double-check all inclusion and exclusion criteria.

8. Obtain informed consent for tPA.

Chapter 23 TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK AND CEREBROVASCULAR ACCIDENT 159

n

Neurosurgical consult for possible evacuation

n

Additionally, for all ICH consider the following general steps using the mnemonic

RAMP It up:

n

Reverse any anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents.

n

Antiepileptics

n

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) reduced to 110 to 130 or 15%

n

Position head of bed to 30 degrees.

n

Intracranial pressure (ICP) control (aggressive measures)

a. Mannitol IV 1 g/kg (then 0.25–0.5 g/kg every 6 hours)

b. Barbiturate coma

c. Hyperventilate (PaCO

2

30–35 mm Hg)

d. Neuromuscular blockage

e. Ventriculostomy

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GI, gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; INR,

international normalized ratio; MCA, middle cerebral artery; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health stroke scale;

NINDS, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial

thromboplastin time; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

NINDS inclusion

criteria:

NINDS exclusion

criteria:

ECASS III additional exclusion criteria

(3- to 4.5-hour time window):

• No age cutoff

• Objective evi-

dence of neu-

rologic deficit

on NIHSS

(scale 0–42)

• Symptom on-

set ,3 hours

(if unknown

timing, last

seen normal

time used; if

still unclear,

exclude)

• Stroke or serious head trauma

,3 months

• Major surgery ,14 days

• Any current or history of ICH

• SBP .185 or DBP .110 (see

Question 28)

• Rapidly improving or minor

symptoms of stroke

• Symptoms suggestive of SAH

• GI or GU hemorrhage ,21 days

• Arterial puncture at noncom-

pressible site ,7 days

• Seizure at onset of stroke

• If on anticoagulation prior

48 hours, PT .15 seconds

(or INR .1.7)

• If on heparin prior 48 hours,

PTT above normal range

• Platelets ,100,000 mm

3

• Blood glucose ,50 mg/dL and

.400 mg/dL

(Note MUST meet NINDS criteria

as well)

• Age ,18 or .80 years old

• Severe stroke, defined as NIHSS

.25 or imaging .

1

⁄3 of

MCA territory

• Combination of previous stroke

and diabetes

• Oral anticoagulation therapy

(warfarin)

• Major surgery or severe trauma

,3 months

• Other major disorders associated

with an increased risk of bleeding

TABLE 23-2. INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA FOR TISSUE PLASMINOGEN ACTIVATOR

Chapter 23 TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK AND CEREBROVASCULAR ACCIDENT160

25. What about recombinant factor VIIa (rF7a)?

rF7a has shown promise for rapid hemostasis in ICH; however, it is associated with an

increased risk of arterial thromboembolic events (i.e., myocardial infarction [MI] or ischemic

stroke), especially at high dosages. Furthermore, a recent phase 3 clinical trial did not

show improvement in 3-month death or severe disability. As such, it remains experimental

at this time.

26. What medications should be started in the ED for acute stroke?

This depends on what type of stroke you’re dealing with and if the patient is a candidate for

tPA. TPA protocol requires no anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy within 24 hours of tPA

administration. For hemorrhagic stroke, see Question 24. For ischemic stroke not receiving

tPA or anticoagulation, early aspirin therapy (325 mg PO) is recommended in the ED, unless

contraindicated. Certain patients with acute ischemic stroke may instead benefit from

anticoagulation.

27. What are the indications for heparin?

There is currently no evidence evaluating early initiation of heparin or low-molecular-weight

heparin in the ED for acute ischemic stroke. Early initiation must be carefully weighed against

the risk of bleeding at the stroke site. However, it may be beneficial to start early in patients

with cardioembolism from intracardiac thrombus, large artery stenosis with intraluminal

thrombus, or cervical or intracranial artery dissection. This decision should ideally be made in

collaboration with a neurologist.

28. How do I approach the stroke patient with hypertension?

Before deciding on management, it is critical to distinguish ischemic from hemorrhagic stroke.

n

Ischemic stroke: Permissive systemic hypertension may be critical to maintaining cerebral

perfusion, and aggressive lowering may result in clinical deterioration. Most experts

recommend lowering slowly by 15% only if systolic blood pressure (SBP) 220 mm Hg or

diastolic blood pressure (DBP0 120 mm Hg. The important exception is when

thrombolytic therapy is being considered. In this setting, one to two dosages of labetalol

intravenously 10 to 20 mg over 1 to 2 minutes is allowed if SBP .185 mm Hg or DBP

.110 mm Hg.

n

Hemorrhagic stroke: The benefits of lowering BP are reduced bleeding and vascular

damage, but again higher than normal BPs may be necessary to optimize cerebral

perfusion. Without ICP monitoring, one should defer to consult recommendations, but a

modest reduction of elevated BPs is reasonable to consider in this setting.

29. What is the best way to minimize risk of litigation for tPA?

Patient care and safety should always be your primary concern. However, one must recognize

that acute ischemic stroke remains a medicolegal target both for failure to treat with tPA and

adverse events associated with tPA therapy. Good medicine is good law. Have a current

multidisciplinary evidence-based stroke protocol and strictly adhere to it. Involve stroke team

consultants early. When possible, obtain written informed consent.

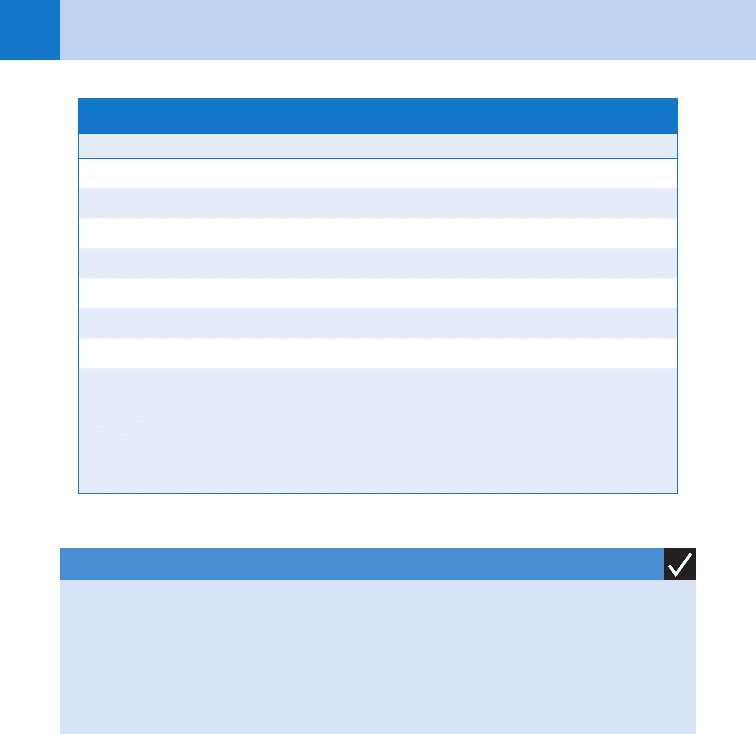

KEY POINTS: MANAGEMENT OF ICH

1. Reverse any anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents.

2. Antiepileptics.

3. MAP control.

4. Position head of bed.

5. ICP control.

Chapter 23 TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK AND CEREBROVASCULAR ACCIDENT 161

30. What if I accidentally give tPA to a stroke mimic?

Evidence is limited, so true safety in this setting is unclear. However, some evidence suggests

this situation may be both safe and rare.

31. Are there alternatives to tPA for acute ischemic stroke?

Intra-arterial thrombolysis and mechanical clot disruption are promising new alternatives for

acute ischemic stroke and may extend the therapeutic window beyond 4.5 hours; however,

these therapies remain experimental and are often limited to academic institutions. Intra-

arterial thrombolysis after systemic tPA is also a promising alternative for community

hospitals in close proximity to academic centers. These alternatives should only be considered

in collaboration with or within a primary stroke center with these capabilities.

32. Which ED patients are at high risk for stroke?

In the ED, three groups of patients are potentially identifiable before a stroke occurs.

a. Acute MI: Most emboli associated with MI occur soon after MI. Patients with anterior wall

MIs are at highest risk. Appropriate intervention with anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy

in the ED may prevent a stroke a few hours later.

b. Multiple traumatic injuries: These patients are notorious for having a stroke in the

hospital after their “life has been saved.” The highest risk of trauma-related stroke is in

patients with direct trauma to the carotid or vertebral arteries. The vertebral artery is

particularly prone to injury from rapid head motions. Facial fractures have been associated

with a higher risk of carotid injury, leading to carotid occlusion, dissection, or artery-to-

artery embolism. Recognition of high-risk patients and early angiography allow preventive

measures, such as anticoagulation therapy, to be instituted if there are no

contraindications.

c. TIA or recent ischemic stroke: Recall that TIA has a high risk of acute stroke within 2

days. Prompt institution of antiplatelet therapy is worthwhile in the ED and should not be

deferred until the patient is admitted to the hospital floor.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Alberts MJ, Hademenos G, Latchaw RE, et al: Recommendations for the establishment of primary stroke

centers. Brain Attack Coalition. JAMA 283:3102–3109, 2000.

2. Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al: Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific

statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association

Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and

Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular

Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for

neurologists. Stroke 40:2276–2293, 2009.

3. Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al: Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke.

N Engl J Med 359:1317–1329, 2008.

4. Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al: Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early

stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 369:283–292, 2007.

5. Lavallee PC, Meseguer E, Abboud H, et al: A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access

(SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol 6:953–960, 2007.

6. Liang BA, Zivin JA: Empirical characteristics of litigation involving tissue plasminogen activator and ischemic

stroke. Ann Emerg Med 52:160–164, 2008.

7. Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al: Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice, ed 6,

Philadelphia, 2006, Mosby/Elsevier.

8. Mayer SA, Brun NC, Begtrup K, et al: Efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII for acute

intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 358:2127–2137, 2008.

9. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al: Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and

minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential

comparison. Lancet 370:1432–1442, 2007.

Chapter 23 TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK AND CEREBROVASCULAR ACCIDENT162

10. Scott PA, Silbergleit R: Misdiagnosis of stroke in tissue plasminogen activator-treated patients: characteristics

and outcomes. Ann Emerg Med 42:611–618, 2003.

11. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and

Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med 333:1581–1587, 1995.

12. Weintraub MI: Thrombolysis (tissue plasminogen activator) in stroke: a medicolegal quagmire. Stroke

37:1917–1922, 2006.

13. Winkler DT, Fluri F, Fuhr P, et al: Thrombolysis in stroke mimics: frequency, clinical characteristics, and

outcome. Stroke 40:1522–1555, 2009.

163

CHAPTER 24

MENINGITIS

Maria E. Moreira, MD

1. What is meningitis? Why is it important?

Meningitis is an inflammatory disease of the tissues surrounding the brain and spinal

cord. Mortality from bacterial and fungal meningitis is 10% to 30%. Prompt recognition

and treatment of bacterial meningitis can lessen morbidity and mortality.

2. What are the causes of meningitis?

See Table 24-1.

3. Which organisms are most commonly involved in each age group?

See Table 24-2.

4. Who is at risk for meningitis?

Those older than 60 and younger than 5 are at highest risk. Medical conditions that put

patients at risk include: diabetes, alcoholism, cirrhosis, sickle cell disease, immunosuppressed

states, history of splenectomy, thalassemia major, bacterial endocarditis, malignancy, history

of ventriculoperitoneal shunt, and intravenous drug abuse. Other risks include recent exposure

to others with meningitis, crowding, contiguous infection (e.g., sinusitis), and dural defect

(e.g., traumatic, surgical, congenital).

5. List the common presenting symptoms of meningitis.

n

Fever (most sensitive sign)

n

Change in mental status

n

Headache

n

Photophobia

n

Stiff neck

n

Lethargy

n

Irritability

n

Malaise

n

Confusion

n

Seizures

Infectious causes Noninfectious causes

Bacteria Neoplastic

Viruses Collagen vascular

Fungi Drugs (i.e., antibiotics and

anti-inflammatory medications)

Parasites

Tuberculosis

TABLE 24-1. CAUSES OF MENINGITIS

Chapter 24 MENINGITIS164

6. What clinical signs are characteristic of meningeal irritation?

n

Nuchal rigidity

n

Brudzinski’s sign: flexion of the neck results in flexion of the knees and hips

n

Kernig’s sign: pain or resistance of the hamstrings when the knees are extended with the

hips flexed at 90 degrees

n

Jolt accentuation: baseline headache increases when the patient turns the head horizontally

two to three rotations per second. (This physical finding is found more reliably in

meningitis than are the previously mentioned physical findings.)

These findings are often absent in the very young and older patients.

7. List the presenting signs of meningitis in infants.

n

Bulging fontanelle (may not be present if patient is dehydrated)

n

Paradoxic irritability (quiet when stationary, cries when held)

n

High-pitched cry

n

Hypotonia

n

Skin or spine may have dimples, sinuses, nevi, or tufts of hair indicating a congenital

anomaly communicating with the subarachnoid space.

8. If the symptoms are not specific and physical findings are absent, what are

the indications for lumbar puncture (LP)?

LP should be done whenever meningitis is suspected because analyzing spinal fluid is the only

way to diagnose meningitis.

Age or Condition Most Commonly Encountered Organisms

Newborns Group B or D streptococci, nongroup B

streptococci, Escherichia coli

Infants and children Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria

meningitides, Haemophilus influenzae

Adults S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, N. meningitides,

staphylococci, streptococci, Listeria spp.

Patients with impaired cellular immunity Listeria monocytogenes, gram-negative bacilli,

S. pneumoniae, N. meningitides

Head trauma, neurosurgery, or CSF shunt Staphylococci, gram-negative bacilli,

S. pneumoniae

TABLE 24-2. ORGANISMS MOST COMMONLY INVOLVED BY PATIENT GROUP

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

KEY POINTS: CLASSIC CLINICAL TRIAD FOR MENINGITIS

1. The classic clinical triad of fever, neck stiffness, and altered mental status is present in less

than two thirds of patients with meningitis.

2. The absence of all three signs of the classic triad virtually eliminates a diagnosis of

meningitis.

Chapter 24 MENINGITIS 165

9. What tests should be done before doing an LP?

a. Funduscopic examination—check for papilledema and spontaneous venous pulsations.

b. Computed tomography (CT) scan—order only if following are present: papilledema,

absence of spontaneous venous pulsations, altered mental status, focal neurologic

examination, new-onset seizure, or clinical suspicion for recent trauma or subarachnoid

bleed.

c. Coagulation studies and platelet count—if suspicion for bleeding disorder.

10. What is the most common error in ED management of meningitis?

Delaying administration of antibiotics until the LP is done. If there is a clinical suspicion of

bacterial meningitis, antibiotics should be administered promptly. Intravenous antibiotics given

2 hours or less before the LP (and ideally after blood and urine cultures are obtained) will not

affect the results of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis.

11. Discuss the risks of LP.

n

Paralysis: unlikely (needle inserted below level of spinal cord at L2 or below)

n

Transient leg paresthesias during LP: due to irritation of nerve roots by the needle

n

Cauda equina syndrome: from hematoma in patients with coagulopathy (rare)

n

Headache: most common sequela, seen in 5% to 30% of patients

n

Tonsillar herniation: from increased intracranial pressure (no risk with normal CT)

12. What is the secret to performing LP successfully?

Proper positioning of the patient is crucial. If the LP is done with the patient lying down, be

sure the shoulders and hips are in a straight plane perpendicular to the floor. The patient

should be in the tightest fetal position possible. If the LP is done with the patient sitting up,

have the upper body rest on a bedside table and have the patient push his or her back toward

you as if he or she is an angry cat.

13. When is it essential to perform the LP with the patient lying down?

This is important when you want to obtain an opening pressure. If you are unable to perform

the LP with the patient lying down, you can place the needle with the patient sitting up and

then have him or her lay down to obtain the opening pressure.

14. What can cause a falsely elevated intracranial pressure?

A tense patient, the head being elevated above the plane of the needle, marked obesity, or

muscle contraction.

15. Which laboratory studies should be ordered on the CSF?

Four tubes are usually collected, each containing 1 to 1.5 mL. More CSF is needed if special

tests are required.

n

Tube 1: Cell count and differential

n

Tube 2: Gram stain, culture, and sensitivities (special tests that may be ordered include

viral cultures, tuberculosis cultures and acid-fast stain, fungal antigen studies and India ink

stain, and serologic tests for neurosyphilis. Countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis is used

occasionally to detect specific bacterial antigens in the CSF.)

n

Tube 3: glucose and protein

n

Tube 4: cell count and differential

In pediatric patients, three tubes are collected: tube 1 for microbiology, tube 2 for glucose and

protein, and tube 3 for cell count and differential.

16. What findings on LP are consistent with bacterial meningitis?

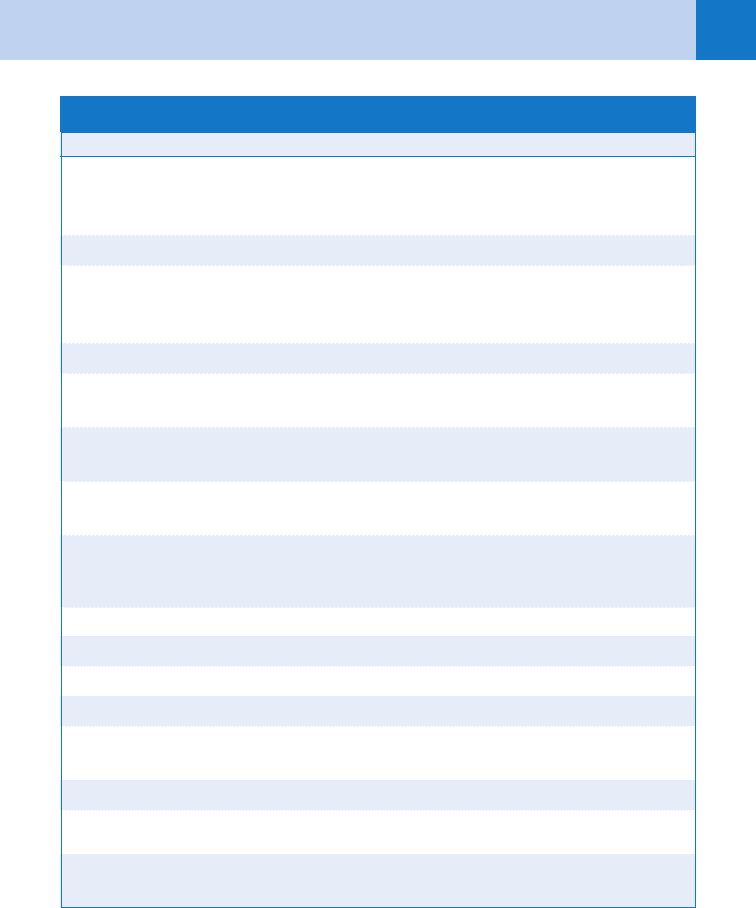

See Table 24-3.

Chapter 24 MENINGITIS166

17. Which antibiotics should be prescribed when the causative organism is

unknown?

See Table 24-4.

18. What about steroids?

The rationale behind the use of steroids is that attenuation of the inflammatory response in

bacterial meningitis may be effective in decreasing pathophysiologic consequences such as

cerebral edema, increased intracranial pressure, and altered cerebral blood flow. The current

recommendations are listed here:

n

The Infectious Disease Society of America includes dexamethasone in its algorithm for

treatment of meningitis both in adults and in infants.

n

Use dexamethasone (0.15 mg/kg) in adults with suspected or proven pneumococcal

meningitis. Then only continue if CSF Gram stain shows gram-positive diplococci.

n

Use dexamethasone (0.15 mg/kg) in children with suspected or proven Haemophilus

influenzae meningitis.

n

Do not give dexamethasone to adult patients who have already received antimicrobial

therapy.

KEY POINTS: CORRECTIONS FOR TRAUMATIC TAPS

1. CSF from a traumatic LP should contain 1 white blood cell (WBC) per 700 (red blood

cells (RBCs).

2. When traumatic LP has occurred, correct CSF protein for the presence of blood by

subtracting 1 mg/dL of protein for each 1,000 RBCs.

3. A high CSF protein level associated with a benign clinical presentation should suggest

fungal disease.

Parameter Finding

Opening pressure In range of 20–50 cmH

2

O

Appearance Cloudy

White blood cell count 1,000–5,000 cells/mm

3

Cells Neutrophil predominance

Glucose ,40 mg/dL

Ratio of CSF to serum glucose ,0.4

CSF protein Elevated (often .100 mg/dL)

CSF lactate .3.5 mmol/L (more useful in postoperative

patients than in community-acquired meningitis)

TABLE 24-3. FINDINGS CONSISTENT WITH BACTERIAL MENINGITIS

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Chapter 24 MENINGITIS 167

19. Do people exposed to a patient with meningitis need antibiotics?

Individuals who have had close contact with someone who has, or is suspected to have,

meningococcal meningitis should take rifampin, 600 mg twice a day for 2 days. Other

accepted prophylaxis regimens for Neisseria meningitides include the following: ciprofloxacin,

500-mg single dose; ceftriaxone, 250-mg intramuscular (IM) dose (used in pregnancy); or a

single oral dose of azithromycin, 500 mg. A 4-day course of rifampin is recommended for

most individuals who have been in close contact with someone with H. influenzae type B

meningitis. Individuals exposed to someone with another type of meningitis, especially viral,

do not need prophylactic antibiotics.

Organism Antibiotic Treatment

Neisseria meningitides Penicillin G, 3–4 million IU IV every 4 hours,

or ampicillin, 2 g IV every 4 hours, or third-

generation cephalosporin

Streptococcus pneumoniae Vancomycin plus a third-generation cephalosporin

Haemophilus influenzae Cefotaxime, 2 g IV every 6 hours or Ceftriaxone

2 g IV every 12 hours or Chloramphenicol

50–100 mg/kg/day in four divided doses

Staphylococcus aureus Nafcillin 2 g IV every 4 hours

Escherichia coli and other gram-negative

enterics except Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Cefotaxime, 2 g IV every 4 hours

P. aeruginosa Ceftazidime, 2 g IV every 8 hours, plus gentamicin,

3–5 mg/kg/day IV in three divided doses

Listeria monocytogenes Ampicillin, 2 g IV every 4 hours, plus gentamicin

(as for P. aeruginosa)

Group B streptococci Penicillin G 4 million units IV every 4 hours

or Ampicillin 2 g IV every 4 hours

Generalized (empiric Rx) recommendations

Age or condition Antibiotic treatment

Age ,3 months Ampicillin 1 broad-spectrum cephalosporin

Age 3 months to 50 yr Vancomycin 1 broad-spectrum cephalosporin

Age .50 yr Ampicillin 1 broad-spectrum cephalosporin

1 vancomycin

Impaired cellular immunity Ampicillin 1 ceftazidime 1 vancomycin

Head trauma, neurosurgery, CSF shunt Vancomycin 1 ceftazidime

TABLE 24-4. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR KNOWN ORGANISMS AND GENERALIZED RECOMMENDATIONS

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; IV, intravenously.