Lima J.J.Pedroso, de (ed.). Nuclear Medicine Physics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

438 Nuclear Medicine Physics

0°

Electron

Photon

Photon

E

θ

ϕ

E′< E

E′

T

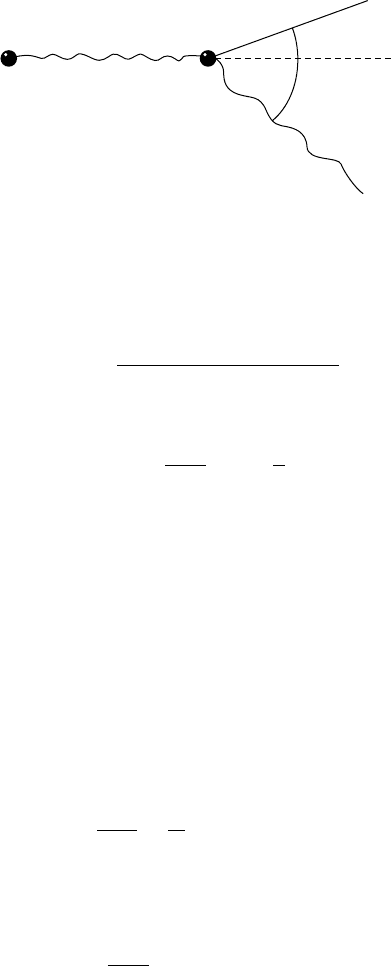

FIGURE 8.2

Kinematics of the Compton effect.

One can obtain the following kinematic equations for the Compton effect,

w

=

w

1 +(w/m

0

c

2

)(1 −cos φ)

, (8.11)

T = w −w

, (8.12)

cot θ =

1 +

w

m

0

c

2

tan

φ

2

, (8.13)

where m

0

c

2

(rest mass energy of the electron) is 0.511 MeV; and the energies

w, w

, and T are expressed in MeV.

8.2.4 Thompson Scattering

In the Thompson description, both the incident photon and the scattered

photon have the same energy. The electron does not acquire kinetic energy as

a result of the elastic collision.

Thompson pointed out that considering the differential cross-section per

electron for a photon scattered at an angle φ, per unit of solid angle, one can

write

d

e

σ

0

dΩ

φ

=

r

2

0

2

(1 +cos

2

φ), (8.14)

in units of (cm

2

sr

−1

per electron), where

r

0

=

e

2

m

0

c

2

= 2.818 ×10

−13

cm, (8.15)

which is named the classic radius of the electron; and the subscript e in

e

σ refers

to a cross-section per electron.

Dosimetry and Biological Effects of Radiation 439

We can conclude that there is a forward–reverse symmetry, meaning that

Equation 8.14 has the same value for φ = 0

◦

and φ = 180

◦

and has half of this

value for φ = 90

◦

.

The total cross-section per electron,

e

σ, is obtained by integration of Equa-

tion 8.14 over all possible scattering angles. A further simplification can be

introducedby assuming cylindrical symmetry and integrating over 0 ≤ φ ≤ π

and dΩ

φ

= 2π sin φ dφ.

e

σ =

π

φ=0

d

e

σ

0

= πr

2

0

π

φ=0

(1 +cos

2

φ) sin φ dφ, (8.16)

e

σ =

8πr

2

0

3

= 6.65 ×10

−25

cm

2

/electron. (8.17)

This leads to a value independent of the energy.

It is well known that this cross section can be viewed as an effective target

area and is numerically equal to the probability of occurrence of a Thomp-

son scattering when a photon crosses a layer that contains one electron

per cm

2

.

8.2.5 Klein–Nishina Cross Section for the Compton Effect

In 1928, Klein and Nishina applied the Dirac relativistic theory of the electron

to the Compton effect in order to obtain better values for the cross section.

The value obtained by Thompson (Equation 8.17), which is independent of

the energy, has an error that can be up to a factor of 2 for energies of the order

of 0.4 MeV. Klein and Nishina have had success in reproducing the values

experimentally obtained, even assuming free electrons, initially at rest.

The differential cross-section for the scattering of a photon over an angle φ,

per unit of solid angle and per electron, is given by

d

e

σ

0

dΩ

φ

=

r

2

0

2

w

w

2

w

w

+

w

w

−sin

2

φ

, (8.18)

where the energy w

is given by Equation 8.11 and the subscript e in

e

σ refers

to the cross-section per electron.

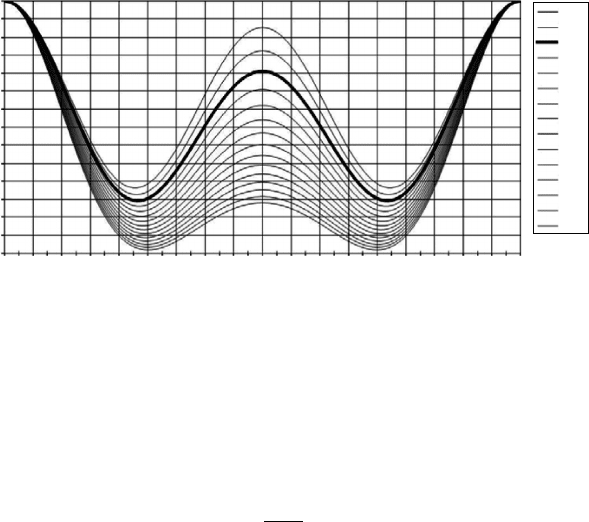

Equation 8.18 is graphically shown in Figure 8.3.

It can be seen that the highest probabilitiesoccur for angles near the incident

axis. For backscattering, that is, angles between 90

◦

and 270

◦

, the highest value

for the probability is at exactly 180

◦

.

For lower energies, w

= w, and Equation 8.18 is reduced to the Thomp-

son expression (Equation 8.14).

440 Nuclear Medicine Physics

20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180

Angle (degree)

200 220 240 260 280 300 320 310 360

150

140

130

120

110

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

0.3

0.35

0.4

0.45

0.5

0.55

K-N cross section/r

0

0.6

0.65

0.7

0.75

0.8

0.85

0.9

0.95

1

2

FIGURE 8.3

Klein–Nishina cross-section for several values of the energy in the range 10–150 keV.

The Klein–Nishina total differential cross section per electron is obtained

by integration of Equation 8.18 over all scattering angles,

e

σ = 2π

π

φ=0

d

e

σ

dΩ

φ

sin φ dφ

(8.19)

8.2.6 Corrections of the Bonding Energy

of the Electrons

In the theory of gamma radiation transport, the bond energy of the electrons

is, in general, approximately ignored or treated. The justification for this is

that for elements of low Z, the bonding energies in the K shell are small when

compared with the photon energies; whereas for materials with high Z (with

rather high bonding energy in shell K), these electrons are a small fraction of

the total.

In the Compton effect, a photon collides with one of the atomic electrons,

transferring some of the momentum. When the electron acquires enough

energy, it escapes from the atom or is excited to an unoccupied atomic level. If

the energyis very small for any of these possibilities, then the electron remains

bonded in its orbital, and the atom reacts as a single entity. In general, as the

bonding energies are small compared with the photon energies, the electron

is released, leaving the excited ion with an excitation energy equal to the

bonding energy of the shell from which the electron was removed. After the

previous process, the atom returns to the ground state through the emission

of fluorescent photons and Auger or Coster-Kroning electrons. The Comp-

ton effect is similar to the photoelectric effect, as in both interactions there

Dosimetry and Biological Effects of Radiation 441

is energy transfer, leading to the appearance of an energetic electron and an

ionized atom.

In general, as has already been mentioned, ionization or excitation of

the atom is not considered in the energy transfer process in the Compton

interaction. It is assumed that the bond energy of the electron is less than the

energy acquired in the collision; and, therefore, the ionization energy of the

atom is ignored. This approach was considered by Klein and Nishina when

they assumed that there is a free electron.

When the bond energy in the atom is considered, the treatment of the

collision becomes considerably more complex.

There are two conditions where the ionization energy of the atom is not

small compared with the kinetic energy of the electron. These are (a) for all

photon energies where a scratching collision occurs and (b) for photons with

lowenergywhere, for all collision angles,the bond energycannot be neglected

[2]. These conditions depend on the atomic number and the shell where the

collision occurs.

The bonding corrections are often treated in the Waller–Hartree or impulse

approximations [3], which take into account not only the K shell but also the

atomic electrons.

These calculations involve the application of a multiplicative factor, termed

the incoherent scatter function, S(q, Z), to the expression of the Klein–Nishina

differential cross section [4]

dσ(θ)

dΩ

= S(q, Z)

dσ

KN

(θ)

dΩ

(8.20)

where q is the momentum transferred. In the impulse approximation, S(q, Z)

represents the probability of an atom leading to any excited or ionized state

as a result of a sudden impulsive action that supplies a (recuo) momentum q

to an atomic electron.

The expression impulse approximation results from the assumption that the

interaction between both the radiation field and the atomic electron happens

in such a short time that the electron sees a constant potential.

The calculation of S(q, Z), which depends on knowledge of the atomic wave

function, can be made for hydrogen and for other atoms using several meth-

ods of approximations based on the models of Thomas–Fermi, Hartree, and

others.

Ribberfords and Carlsson [3] calculated σ

en

using the impulse approxima-

tion. They pointed out that the tables of Hubbel [5] and Storm and Israel [6]

have considerable errors for photon energies less than 200 keV, particularly

for materials of high atomic number.

Experimental results shows that both approximations, impulse and Waller–

Hartree, can give considerable errors for atomic numbers Z > 50. Though for

higher Z values, these approximations need more refinements, they can be

used for low Z materials.

442 Nuclear Medicine Physics

8.2.7 The Photoelectric Effect

Theoretical analysis of the photoelectric effect is difficult, because the wave

functions of the final states, which are solutions of the Dirac relativistic

equation of the scattered electron, can only be obtained in the exact form

as an infinite sum of partial waves. In addition, for high energies, a large

number of terms are needed.

This is more complex than the Compton effect due to the existence of the

bonding energy of the electron, and there is no simple equation, such as that

of Klein–Nishina discussed earlier.

The wave function of the initial state for the bond electron is, in general,

assumed to be an electron state in a central potential of the nucleus, and the

effect of all the remainder electrons in the atom are taken in account as if the

field of the nucleus has an electric charge Z −S

i

. The constant S

i

is named the

shielding constant and represents the decrease of the nuclear electric charge

arising from the presence of all the electrons of the atom. For further analysis,

see, for example, Davisson [7].

In the photoelectric effect, a photon disappears and an electron is ejected

from the atom. Instead of looking at this interaction as an effect between a

photon and an electron, it must be seen as a process between a photon and an

atom. In fact, complete absorption between only a photon and a free electron

cannot occur, because the linear momentum will not be conserved [8].

The nucleus absorbs the momentum but acquires relatively little kinetic

energy due to its large mass. It is clear that the photoelectric effect can only

occur if the incident photon has energy greater than the bonding energy of

the electron that will be removed. The hole created by the ejected electron is

filled by electrons from any outer orbital, which can simultaneously produce

fluorescence radiation, emission of Auger electrons, or both.

The competition between the emissions of a fluorescent K photon and the

emission of Auger electrons is described by Y

K

, termed the fluorescence yield

of the K shell, which is defined by the number of K photons emitted per hole

in the shell K. The probability that a photon K will be emitted is nearly 1 for

elements with high Z and almost zero for materials with low Z.

Inthe photoelectric effect, the photoelectronacquiresenergyw −E

s

,where

E

s

is the bonding energy of the shell from where the photon was ejected. In

the filling of the holes created, on average, part of the energy, E

s

, is emitted

as characteristic radiation, whereas part is deposited through Auger elec-

trons. For this reason, the mean energy transferred (to electrons),

¯

E

tr

,inthe

photoelectric process is given by

w −E

s

<

¯

E

tr

< w. (8.21)

For materials with high Z, this becomes more complicated [9]. For tissue

equivalent materials of interest in radiological applications, it is much sim-

pler, because in these materials the bonding energies of the K shell are very

small (approximately 500 eV); therefore, the photoelectron acquires almost

Dosimetry and Biological Effects of Radiation 443

all the photon energy, meaning that

¯

E

tr

= w and the coefficients of transfer

and attenuation can be considered to be equal. Since the photoelectric pro-

cess is important only for low energies, the “bremsstrahlung” produced by

the ejected electrons can be neglected, and then the absorption and transfer

coefficients are numerically identical.

The published tables are based on experimental results, complemented by

theoretical interpolations for other energies and absorption media, and give

satisfactory results for several regions of energy values.

8.2.8 Pair Production

Pair production is a process whereby a photon disappears, producing an elec-

tron and a positron. Often, this is mentioned as a process of materialization.

The pair production occurs only in a field of a Coulombic force, gener-

ally near an atomic nucleus; however, it can occur in a field of an atomic

electron. This latter process is named as triplet production, because the host

electron,which furnishes the Coulombic field, also acquires significant kinetic

energy due to the conservation of momentum. This results in emission of two

electrons and a positron from the site of interaction.

Obviously, a minimum of 2mc

2

= 1022 MeV will be needed for pair pro-

duction to occur in the nuclear field. Since we are more interested in energies

below 1 MeV, this process will not be further developed.

8.2.9 Rayleigh Scattering

Rayleigh scattering, also called resonant scattering by an electron, is an atomic

process where an incident photon is absorbed by a weakly bound electron.

The electron is excited to a state of higher energy, and a second photon of

the same energy is emitted; whereas the electron returns to its initial state,

such that there is no excitation. The recoil of the scattered photon is actually

taken by the whole atom, with a very small transference of energy, so that the

energy lost by the photon is negligible.

This process is elastic. The atom is neither excited nor ionized. Some authors

[9] have described Rayleigh scattering as a cooperative phenomenon that

involves all the electrons of the atom. The photons are scattered by the bound

electrons in a process where the atom is neither excited nor ionized. The

process occurs mainly at low energies, and for materials of high Z, in the

same region where the effects of the bonding electrons influence the Compton

cross section.

Since the scattering of the photon results from the reaction of the whole

atom, it is often termed coherent scattering.

Rayleigh scattering does not contribute to the kerma or the absorbed dose,

becausethereis no energyfurnished toany chargedparticle, and noionization

or excitation is produced.

444 Nuclear Medicine Physics

8.2.10 Photonuclear Interaction

In a photonuclear interaction, an energetic photon (>MeV) enters and excites

a nucleus that will emit a proton or a neutron. The protons contribute to

the kerma. However, the relative amount remains below 5% of that due to

the pair production; and, therefore, in general, these are not considered in

dosimetry. Neutrons do already have practical importance, because they pro-

duce problems in radiation protection. This happens in some clinical electron

accelerators, where energies involved can be greater than 10 MeV.

Since we are, in general, interested in energies below 1 MeV, we will not

make any further considerations about photonuclear interaction.

8.2.11 Interaction Coefficients

For x- and γ-rays, the mass attenuation linear coefficient is often used. This is

given by

μ

ρ

=

τ

ρ

+

σ

C

ρ

+

σ

coh

ρ

+

κ

ρ

(8.22)

whose units are (m

2

kg

−1

) and the components refer to photoelectric effect,

Compton effect, coherent scatter, and pair production, respectively.

The mass energy transfer coefficient is given by

μ

tr

ρ

= f

τ

τ

ρ

+f

C

σ

C

ρ

+f

κ

κ

ρ

(8.23)

also in units of (m

2

kg

−1

), and where the components refer to photoelec-

tric effect, Compton effect, and pair production, respectively. The weights

f

τ

, f

C

, and f

κ

are conversion factors which indicate for each interaction the

fraction of the photon energy that, eventually, is converted into kinetic energy

of electrons and is dissipated in the medium through losses in collisions, ion-

izations, and excitations. The coherent scattering is excluded, because in this

process there is no transference of energy.

The mass energy absorption coefficient for x- and γ-rays is given by

μ

en

ρ

=

μ

tr

ρ

(1 −g) (8.24)

in (m

2

kg

−1

), where g represents the fraction of the energy of secondary

charged particles (for photons, these charged particles are electrons) that is

emitted as bremsstrahlung.

Dosimetry and Biological Effects of Radiation 445

For compounds and mixtures, we have,

μ

ρ

mixture

=

i

f

i

μ

ρ

i

, (8.25)

μ

tr

ρ

mixture

=

i

f

i

μ

tr

ρ

i

, (8.26)

where f

i

is the relative fraction of the element i of the compound or mixture.

We can also write,

μ

en

ρ

mixture

=

i

f

i

μ

en

ρ

i

, (8.27)

or in the exact form

μ

en

ρ

mixture

=

μ

tr

ρ

mixture

(1 −g

mixture

). (8.28)

8.3 Interaction of Radiation with Matter: The Electrons

8.3.1 Introduction

As mentioned earlier, interactions of the photon with matter will eject

electrons from atoms.

At a first step, the photons transmit their energy to electrons, which will

then transfer their energy to matter; this second step is named deposition of

energy within matter. In the following part, we will describe the processes of

energy deposition.

The main difference between the interactions of photons and electrons is

that, in general, photons undergo a relatively small number of interactions

(something between 2 and 3 and 20 and 30, depending on their energy)

involving relatively large losses of energy; whereas the electron suffers a

large number of interactions (thousands), each involving only a very small

amount of energy. As a first approximation, we can consider that the electrons

continuously lose energy along their track.

8.3.2 Radiative Energy Loss

According to classic electromagnetic theory, it is well known that a charged

particle, such as the electron, submitted to acceleration (curvilinear tracks in

Coulombic fields, for example) emits radiation. Traditionally, the radiation

produced by electrons submitted to acceleration is named bremsstrahlung,or

446 Nuclear Medicine Physics

braking radiation. This type of radiation is called x-rays when it is produced

in an x-ray tube.

The energy lost by an electron is approximately proportional to its kinetic

energy. The fraction of energy lost by an electron through this process is only

1% of the total loss due to interactions within the medium, for electrons with

energy of the order of 1 MeV. Only for electrons with energy greater than

100 MeV does the radiative process dominate. In a material of high atomic

number, for example, lead, the situation is different and the radiative process

exceeds any other energy loss process even for 10 MeV.

8.3.3 Loss of Energy by Collision

Collisions with the atomic electrons are the most important mechanisms of

loss of energy in matter, resulting in excitation or ionization of the material

traversed.

The loss of energy, dE, along the track dl (dE/dl) is proportional to the

electron density of the material traversed.

Applying quantum mechanical theory, one obtains,

dE

dl

col

∝

q

2

ρ(Z/A)

v

2

ln(1/I), (8.29)

where q is the electric charge, ρ is the density of the material, Z/A is the

quotient between the atomic number and the atomic mass, v is the velocity,

and I is the mean ionization potential.

8.3.4 Stopping Power

The quotient (dE/dl) is known as the linear stopping power of a material for a

charged particle with energy E.

As already mentioned, the loss of the energy of the electrons has two main

components, one due to losses by collisions and the other due to radiative

losses (we will not consider here losses of energy by nuclear reactions).

We can write,

S =

dE

dl

col

+

dE

dl

rad

, (8.30)

that is, the total stopping power is equal to the sum of the collision stopping

power and the radiative stopping power.

Massexpressionsareoften used,dividing thestopping power bythe density

of the material, ρ.

Since the stopping power is proportional to the density, the mass stopping

power is independent of the density.

In dosimetric issues, the restricted mass stopping power, (S/ρ)

Δ

, is often

used, where losses of energy greater than Δ are not considered.

Dosimetry and Biological Effects of Radiation 447

8.3.5 Linear Energy Transfer, L

Δ

, LET

Considering the effects of electrons in matter and specifically with relation

to the biological effects of radiation, in general, we are more interested in

how the energy is deposited in the material irradiated rather than in how

the particle loses its energy. Some collisions of the electrons produce new

electrons that have sufficient energy to escape from the track of the initial

electron leading to small tracks. These electrons are called δ-rays, and their

energy is not deposited in the neighborhood of the initial electron track.

The energy locally deposited can be determined by ignoring all the losses

of the initial electron energy that produce δ-rays with energy above a given

value Δ. Therefore, L

Δ

, the restricted linear energy transfer is defined that

equals the stopping power if we restrict consideration to energy losses less

than Δ, that is,

L

Δ

=

dE

dl

Δ

. (8.31)

Generally speaking, Δ is expressed in keV. If Δ =∞, then there are no

restrictions to the loss of energy, and one can write L

Δ

= S

col

, which is termed

unrestricted linear energy transfer.

8.3.6 Range and CSDA

We can define the range R of a given charged particle in a given medium as

the mean value, p, of the length of the track traveled until rest (neglecting

thermal movement).

Additionally, we can also define the projected range,

t

, of the charged

particle of a given type and initial energy, in a given medium, as the expected

value of the greatest penetration depth, t

f

, of the particle along its initial

direction. In Figure 8.4, the concepts of p and t

f

are outlined.

Another important concept, available in tables published by several

authors, is the continuous slowing down approximation (CSDA) range.

For electrons, the CSDA range is calculated using the equation

R

CSDA

=

T

0

0

dT

dx

−1

dT. (8.32)

For materials with low atomic number, Z, the value of t

max

is comparable

to the CSDA range, which has useful consequences for the application of

tables of the range of electrons. It may be possible that these quantities will

not be useful to describe the electron penetration due to the large number of

interactions.