Lima J.J.Pedroso, de (ed.). Nuclear Medicine Physics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

298 Nuclear Medicine Physics

receptors. Regarding tyrosine kinase receptors, we can refer to the platelet-

derived growth factor-B receptor (PDGF-R), the vasoendothelial growth

factor receptor (VEGF-R), the insulin receptor, the insulin-like growth fac-

tor type-1 receptor, the EGF-R, and the fibroblast growth factor recep-

tors 1 and 4. With regard to the nontyrosine kinase receptors, we have

the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor and the β-subunit of interleukin-2

receptor [192].

Similar to trastuzumab for the treatment of breast cancer, other antibodies

and peptide antagonists have been developed to explore receptors as thera-

peutic targets. As a consequence, several receptors are considered as targets,

particularly the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor, the EGF-R, the PDGF, and

VEGF receptors.

As in the trastuzumab example, too, the use of ligands labeled with radio-

active isotopes can give information about the correct choice of therapy as

well as allow the monitoring of anticancer therapy [193].

Severalligands have been tested in this context. Examples are theligands for

the endothelin receptors such as PD156707 labeled with

11

C(

11

C-PD156707)

and FBQ3020 labeled with

18

F(

18

FBQ3020), the oxytocin analog ligands such

as DOTA-lys8-vasotocin labeled with

111

In (

111

In-DOTA-lis8-vasotocin), and

a specific ligand for melanoma, N-(2-diethylaminoethyl)-2-iodobenzamide

labeled with

123

I(

123

I-N-(2-diethylaminoethyl)-2-iodobenzamide).

6.4.13 Molecular Image as Target

After reviewing the several types of approaches to the use of NM, we can say

that molecular imaging provides information about many metabolic steps of

angiogenesis, hypoxia, and the different transformations and genetic changes

of cells.

In oncology, the added value of molecular imaging is the possibility of

obtaining functional information related to cell differentiation and thera-

peutic response. This means that discriminating between an inflammatory

reaction and a tumor recurrence, or knowing in advance whether the tumor

will respond to a specific therapy, gives the clinician the ability to wisely

choose which patients to include in a particular therapeutic protocol.

After analyzing the available possibilities for evaluating the various

metabolic pathways through functional imaging, when a malignant trans-

formation occurs, we can say that the agents that can differentiate between

inflammation and tumor recurrence are apoptosis and DNAmarkers, because

they are able to accumulate in cell nuclei. Agents that are able to provide

information in terms of predicting therapeutic response are usually enzy-

matic markers or ligands for membrane receptors. The most commonly

used enzymatic markers are those of glycolysis, hypoxia, and tyrosinase;

whereas the most important receptors are the estrogenic and the androgenic

receptors.

Imaging Methodologies 299

6.5 CNS: Physiological Models and Clinical Applications

6.5.1 Introduction

Now that you have reached this section, we may say that your CNS has

performed important and relatively essential tasks for the reading, appre-

hension, and understanding of the book’s subjects, matters, and goals. You

have probably not noticed the significantly high amount of substrates you

had to use nor even the cellular interaction and coordination mechanisms

you triggered. We are convinced that other readings have already given you

the opportunity to understand that the use of these substrates and fairly

complex mechanisms of the functioning of many millions (approximately

100 ×10

9

) of SNC cells can nowadays be investigated by means of medical

imaging. However, you may have also noticed that new medical imaging

techniques enable us to build functional maps [194] of the CNS, which, to

some extent, refute some of the functional anatomy knowledge so rigorously

and artistically developed by basic research [195] and clinical [196–198] sci-

entists. Very recently, we were stunned by some remarks about the need to

change concepts that we thought were well established: Contrary to the num-

ber of neuronal cells decreasing from birth on, as was previously thought, it

is now considered as certain that these cells can be re-created during our life

[199] to offset functional failure due to disease or trauma—neuronal plas-

ticity. Further, the concept of an anatomical and functional map known as

“homunculus” seems to be under reconsideration [200] in view of the results

of medical imaging research, especially functional magnetic resonance and

optical imaging [201].

The objective of this section is to make you think a little more deeply about

the anatomical and functional bases of CNS medical images, especially those

using radioactive molecules as radiopharmaceuticals. More than just inform-

ing you, our intention is rather to stimulate your curiosity and provide you

with some clues to develop your potential interest in functionally investigat-

ing the CNS by means of medical images obtained with radionuclide-labeled

molecules, that is, radiopharmaceuticals.

So, come along with us through a short summary of the anatomy, physi-

ology, pharmacology, and neuronal interaction mechanisms relevant to the

most important clinical applications in this field of knowledge.

6.5.2 Anatomical Basis

The anatomy of the CNS describes the morphology and macroscopic and

microscopic components of the brain and spinal cord. Here, we will only

remind you of some important aspects to help understand medical images.

The morphological study of the spinal cord and cranial pairs is almost

exclusivelycoveredby magnetic resonanceradiology, which playsthe leading

300 Nuclear Medicine Physics

role in diagnosing disease and evolutive changes. Radiopharmaceuticals are

much more often associated with the study and investigation of brain physi-

ology and pathophysiology, either supra- or infra-tentorial. Therefore,we will

focus on the brain, including the cerebellum and midbrain, with the medulla

oblongata and the pons, where we can find a reticular substance that is func-

tionally implicated in some neurological diseases currently under extensive

research.

6.5.2.1 Brain

Some authors argue that several anatomical features of the brain can be

used as an index of mental capacity [202], including brain weight, predom-

inance of left hemisphere, and the complexity of surface brain gyri of the

frontal and parietal lobes. All these have been reported in brain autopsies by

famous scientists. Even you if find it hard to fully believe in such morpho-

logical assumptions of human intelligence, you will have to consider their

importance in the assessment of qualitative and quantitative studies of brain

functions and diseases [203].

The average weight of an adult brain is approximately 1300 to 1400 g, and

the average volume is about 1400 mL. These figures from postmortem studies

are not error free, especially due to water loss. Structural studies with very

precise spatial and volumetric resolution are possible with MRI. They enable

us to establish such in vivo values by means of automated and semi-automated

algorithms for the extraction of the skull and extracranial structures[204]. This

methodologygives us an in vivo brain volume of 1286.4 ±133mLand 1137.8 ±

109 mLin normal male and female volunteers, respectively. The weight is then

calculated from these volumes using the equation

p

c

= V

T

×1.0365 g mL

−1

+V

L

×1.00 g mL

−1

(6.72)

in which V

T

is the total volume in milliliters and V

L

is the cerebrospinal fluid

volume in milliliters [205,206].

Brain volume is age-related that is, it increases exponentially during child-

hood and adolescence to achieve a peak between 12 and 25 years of age.

From then until the age of 80, the brain volume slowly decreases, with a

reduction of about 26% of the peak value between 71 and 80 years of age. At

that point, brain volume is lower than that of healthy 2- or 3-year-old children.

These findings are very similar to those reported in research using data from

postmortem studies [207].

The brain surface is composed of gray matter (cell bodies of neuronal cells)

gyri with gaps between them—the sulci—filled in by meninges. This surface

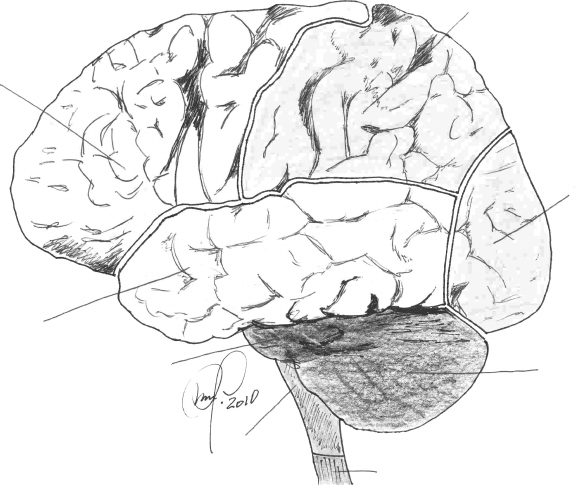

is divided into four lobes, as depicted in Figure 6.36: frontal (8), parietal (1),

temporal (7), and occipital (2) in each of the hemispheres. There are well-

defined geographical boundaries between the frontal and the parietal lobe—

central sulcus or the fissure of Rolando—between the temporal and frontal

Imaging Methodologies 301

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

FIGURE 6.36

Brain surface anatomy as an intracranial component of the central nervous system. For reference,

the cerebellum (3), the medulla oblongata (5), the pons or pons Varolii (6), and the upper end of

the spinal cord (4) are shown.

lobe, including the most anterior and inferior regions of the parietal lobe—

Sylvianor lateralfissure.However,thedivision betweenthe restofthe parietal

lobe and the temporal lobe, between the parietal and the occipital lobes and

between the temporal and the occipital lobes, is simply functional and has no

well-defined geographical representation.

The parietal-temporal-occipital association cortex is located at the most

posterior and inferior region of the cortex (brain surface composed of the out-

ermost brain tissue made of cell bodies—gray matter). As its name implies,

it extends from the parietal cortex to the most posterior area of the temporal

cortex and invades the occipital cortex. Small sulci separate cortical areas with

different cytoarchitecture and functions (52 Brodmann areas; 15 were origi-

nally described) in each lobe. However, there are no geographical boundaries

in the above mentioned association cortex that make an accurate distinction

between parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes possible. Some other functions

arereferenced to cortical areas in two other brain lobes called subsidiary lobes;

one is the insular cortex, which forms the medial wall of the Sylvian fissure or

sulcus, and the other is the limbic cortex or lobe, located above the most ante-

rior (cephalic) or rostral region of the midbrain next to the corpus callosum.

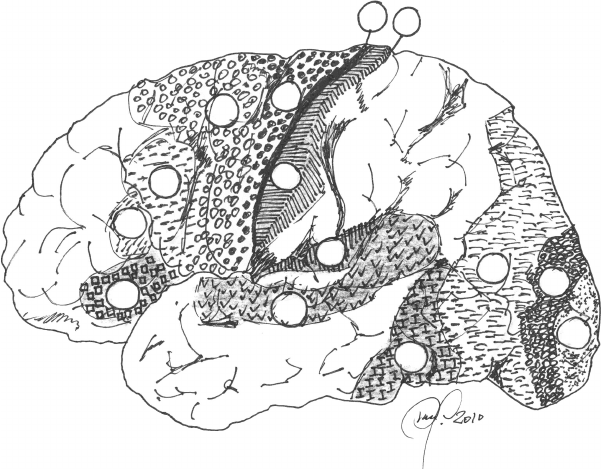

The Brodmann functional areas (Figure 6.37) are a very important working

302 Nuclear Medicine Physics

medium for imaging experts and neurosurgeons conducting brain functional

provocation studies during presurgery preparation in neuro-oncology and

epilepsy.

Within the brain, besides lateral ventricles and most of the white substance

made of axons (some of which are very long) of neuronal cells with soma

(cell body) in the cortex, there are also gray matter nuclei with very impor-

tant regulation and transition functions. These nuclei accommodate synapses

(transitions from presynaptic neurons to postsynaptic neurons) in which neu-

ronalinformation is transmitted either electrically or chemically. Several types

of neurotransmission belonging to different physiological–pharmacological

systems, with such different actions as stimulation or inhibition, may coexist

in the same nuclei. These nuclei can be identified or visualized only by means

of tomography techniques. This chapter does not set out to describe tomo-

graphic anatomy in detail, but in the next section we give an overall idea of

it. We briefly describe some of the problems we face when comparing images

from the same brain section, in the same subject, showing different functions

in the same structures.

1

19

18

17

37

2

3

4

41

44

22

45

47

6

FIGURE 6.37

Brodmann areas on the outer surface of the left hemisphere. Some are worth mentioning as an

example: 1, 2, and 3 (sensory); 4 and 6 (motor and extrapyramidal); 17, 18, and 19 (visual); 22, 37,

41, and 47 (auditory); 44 and 45 (Broca’s speech production).

Imaging Methodologies 303

6.5.2.1.1 In Vivo Comparative Anatomy

The knowledge about CNS morphology and structure, especially the brain,

was fundamentally based on postmortem dissection studies. Even the micro-

scopic structure, described so clearly and accurately by Ramón y Cajal, was

characterized at the expense of painstaking cadaver studies. Today, com-

puterized tomography and MRI studies detect important changes in brain

morphology and architectural structure with a spatial resolution of less than

one millimeter in some cases. Compared with autopsy-derived data, the CNS

structural design above and below the brain tentorium is obtained in an

elegant manner and can be shown in concordance and with the same orienta-

tions. The advent of new sequences used by the most recent MRI instruments

and software broughtfunctionality to brain images. Each image obtained with

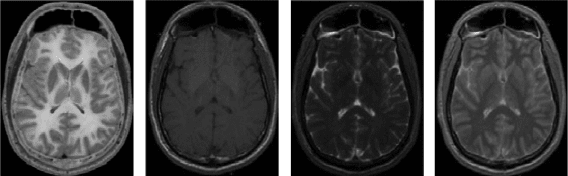

a different sequence also has a different meaning (Figure 6.38).

Even this ability of MRI to offer us high resolution, fine images of the brain

structures with functional characteristics does not depict “life” that is, cog-

nitive function, blood flow, perfusion, or substrate use. To do that, we need

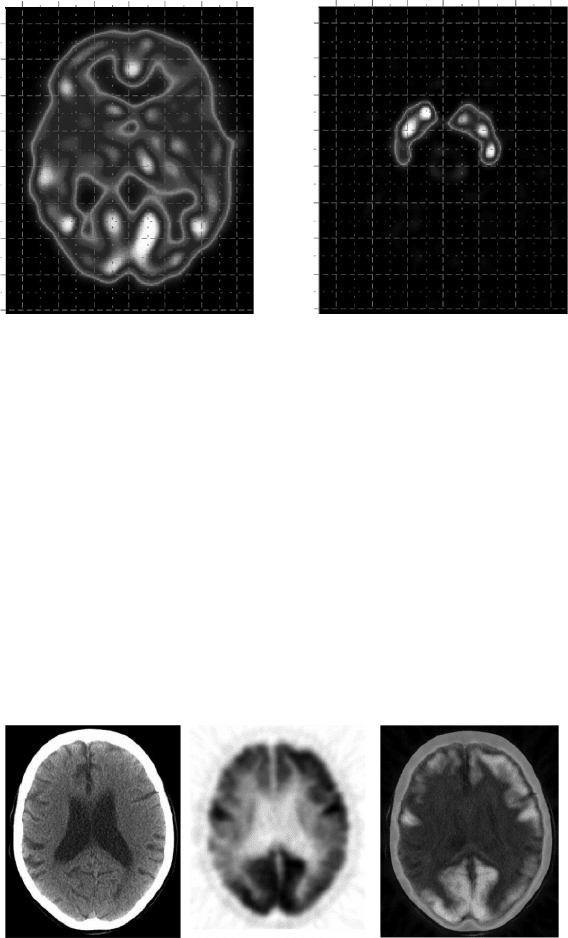

in vivo functional markers, such as radiopharmaceuticals. Figure 6.39 shows

slices taken at the same level as those in Figure 6.38, but this time each slice

has its functional and chemical meaning in vivo. On the left, the distribution

of a radioligand (

99m

Tc-exametazime) whose brain uptake is proportional to

the regional cerebral blood flow (perfusion) is shown. On the right, the dis-

tribution in the same subject (normal volunteer), at the same level, of another

radiopharmaceutical (

123

I-ioflupane), whose image shows the uptake distri-

bution in the basal ganglia, which is directly proportional to the distribution

of dopamine transport systems located on the membrane of the presynaptic

neuronal end, is shown.

All these images need suitable coordinates for intermodality and interfunc-

tion referencing. By defining planar representation grids (such as those in

Figure 6.39) and, more importantly, volumetric representation grids, such as

those defined by Talairach [209], it is possible to superimpose images using

FIGURE 6.38

Images of the same slice (at the level of basal ganglia, with caudate nucleus, lentiform nucleus,

and thalamus in both hemispheres) of one cadaver. The leftmost image is a picture (gray shades)

of the cadaver slice, followed by sequence MR images to demonstrate, from left to right, T1, T2,

and proton density.

304 Nuclear Medicine Physics

100

80

60

40

20

0

20

40

60

60 40 20 0 20 40 60

mm

60 40 20

0

20 40 60

mm

mm

100

80

60

40

20

0

20

40

60

mm

FIGURE 6.39

Comparative functional anatomy obtained from the same normal volunteer, at the level of basal

ganglia, in a transversal slice parallel to the anterior commissure-posterior commissure reference

line, as is usual in neuroimaging. The two slices obtained on different days are referenced to

a grid (1 cm

2

units) similar to the one used by Talairach in his Co-Planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the

Human Brain. (Adapted fromJ. Talairach,P. Tournoux.Translated by Mark Rayport. Thieme Medical

Publishers, Inc., Stuttgart, New York, NY, 1988.)

software and relatively complex algorithms. These images are the coregistra-

tion of anatomical and functional information. Further, these images allow

us to obtain composite maps of the correlation between different functions.

Coregistration techniques are already part of routine clinical application,

for instance, in PET studies with

18

F-DG and CT. Figure 6.40 illustrates an

example of this. The image on the right is the coregistration of the voxel-

by-voxel information from the two images on the left. The leftmost of these

FIGURE 6.40

The images are of transversal slices at the same level (lateral ventricles). From left to right: x-

ray attenuation map (computerized axial tomography, CAT, or CT), distribution map of brain

glucose metabolism (

18

F-DG), and voxel-by-voxel coregistration of both images, that is, glucose

metabolism distribution superimposed on the attenuation map (CT).

Imaging Methodologies 305

represents the attenuation map, and the middle image represents a distribu-

tion map of glucose metabolism in the brain. In this specific case, a marked

reduction of brain metabolism in the parietal cortices (more to the right than

to the left) can be seen, and in the frontal cortices, too (lower than in the pari-

etal cortices), with the metabolism conserved in the motor cortices of both

hemispheres and in the occipital visual cortex. The leftmost CT image only

shows slight ventricular dilatation without further significant abnormalities.

This pattern of cortical hypometabolism is typical of a CNS degenerative dis-

ease evolving into memory loss and other cognitive disturbances typical of

dementia. This is a case of asymmetric Alzheimer’s dementia.

This example shows the simplest method of coregistering images, as the

object (brain) is encased in a static shell (as long as the subject does not move

their head), and the positioning of each voxel containing different informa-

tion is the same in the two acquisitions. In this case, there is no need for

external fiducial markers to act as a reference while the superimposition

program is run. These fiducial markers are contained in the images them-

selves. The two instruments that acquire the images are contiguous, and the

object just moves automatically and with (computer determined) precision

between the CT (left image) and PET (middle image). In other cases, the phys-

ical proximity of data acquisition instruments is not compatible with object

immobilization (the subject), so coregistration has to be digitally performed,

based on more elaborate techniques (see Section 6.3.3). Most of these tech-

niques require the use of mathematical algorithms to manipulate the data in

several ways and directions; consequently, the final product is not error free.

To complicate the coregistration system even more, images have to be often

rescaled, because, during acquisition, voxels of different sizes are used and

this immediately introduces a scale-correction problem. This can be solved,

but artifacts may arise. This can be seen in a recent work comparing the

coordinates from several methods used for brain imaging functional data

analysis [210].

6.5.2.2 Cerebellum

The cerebellum, formed by two lateral lobes and a median lobe, the vermis, is

located under the occipital lobes and is separated from them by a membrane

called the tentorium cerebelli. That is why it is considered infratentorial, simi-

lar to the midbrain, the medulla oblongata, and the pons. The main cerebellar

function is motor coordination, which is very important for maintaining body

posture and balance. For this reason, it receives axons from the brain cor-

tex after they have crossed the middle line. The right cerebellar hemisphere

receives axons originating in the left brain hemisphere and vice versa; the

left cerebellar hemisphere receives axons from the right brain hemisphere.

The cerebellum and periphery (muscular structures) are connected through

the superior, middle, and inferior cerebellar peduncles on the right and left

sides.

306 Nuclear Medicine Physics

6.5.2.3 Midbrain (Mesencephalon)

Referencesto thebrain stemarecommon in theliteraturepublished inEnglish.

This includes the cerebellum, the uppermost part of the spinal cord, the

medulla oblongata, and pons. The latter two together form what is called

the midbrain pons in the Anglo-Saxon literature. In Portugal, we consider

the mesencephalon as the pons or pons Varolii, located between the medulla

oblongata below and the cerebral base above, to which it is connected by the

cerebral peduncles. All the axons communicating between the brain and the

spinal cord and passing through the cerebellum have to pass through the mid-

brain. For the purpose of this book, this section will refer both to the actual

midbrain itself and to the Anglo-Saxon brain stem, because we want to make

it clear that the 12 pairs of cranial nerves that mediate the senses, that is, sight,

hearing, taste, and smell, arise from the lateral sides of the brain stem. Also, all

of them have specific representationin the brain through connections between

their source nuclei and the cortical areas directly related to their functions.

However, it is even more important to mention the formatio reticularis or retic-

ular formation or matter; although this is chiefly a mesencephalic structure,

it also extends to the brain stem from the upper end of the spinal cord to the

base of the cerebral peduncles. The reticular formation or matter is a mixture

of interneuronal arrays forming an intricate network of functional regulation

and modulation between sensitive and sensory neuronal input and peripheral

motor region output of what we call the reflexes.As far as we know, it is in this

mesencephalic area that some inputs are enhanced and maximized, whereas

others are minimized or even suppressed. The main functions of the reticu-

lar formation or matter are based on four types of connections: (1) upward

to the thalamus and cortex, which act as an activation or warning system.

This is especially important in pain perception and its unpleasant connota-

tion; (2) downward to the spinal cord and periphery, which modulate skeletal

muscle tension; (3) input, using cranial pairs, allowing it to modulate heart

rate and blood pressure originating from the carotid sinus (neurovegetative

reflex); and (4) downward through the reticulospinal bundle, ending at the

dorsal horn of the spinal cord and attenuating pain by reducing the effects of

pain-mediating sensitive nerves. In brief, it serves as a high-level controller

between the spinal cord and the brain, which helps responses to undesirable

events,always on thealert andreadytochoose thebestresponseunder normal

functional conditions. Due to its micro-structural complexity, with many axon

branches and neuronal interconnections, reticular formation or matter dys-

function causes poorly identified syndromes, which are sometimes medically

disparaged [211,212].

6.5.3 Physiological and Pharmacological Basis

Substrate input to the CNS obeys pharmacokinetic laws. If we exclude absorp-

tion, that is, the route from the administration site to blood circulation, this

Imaging Methodologies 307

includes a distribution that is directly proportional to local blood flow and,

consequently, to the percentage of blood volume per tissue mass unit (for

the purpose of our case the CNS, chiefly the brain). The substrate may be

present in blood, more specifically in plasma or serum, in its free form or

bound to plasma proteins or blood corpuscles, that is, red blood cells, white

blood cells, and platelets. The substrate concentration available to appear in

brain tissue cells is mainly the substrate concentration in its free form. How-

ever, according to pharmacokinetic principles, a substrate or a drug may be

metabolized (hepatically or by other means) or excreted (hepatically and/or

renally), which tends to reduce plasma-free concentration. This means that

substrates (for the purpose of this book on NM, radiopharmaceuticals) are,

afterintravenous administration,available tobrain tissuedepending on blood

flow distribution. They will have to cross the blood–brain barrier and find

their more-or-less specific binding sites; they may be metabolized in either

the CNS or other organs, and finally a part of the molecules will be excreted,

either via the liver or the kidneys.

The brain and the rest of the intracranial CNS are irrigated by the carotid

(carotid arteries run along the neck’s anterolateral side) and vertebral (ver-

tebral arteries run beside the cervical spine) arterial systems. These arterial

systems communicate with each other both extra- and intracranially. Intra-

cranial communication is better organized. The Circle of Willis is well known:

it is formed by the anterior and posterior communicating vessels connect-

ing anterior and posterior cerebral arteries, respectively. If not permanently

patent, these communications become so in pathological states, so that the

right system may easily supply blood to the left system and vice versa, and

the posterior system may supply blood to the anterior system and vice versa.

Besides these communications, there is also a capillary distribution network

that allows communication among all neighboring vascular territories in the

brain, especially at their boundaries, also called watershed boundaries. It is

essentially here that the development of reactive hyperemia after vascular

insult can be observed, along with the formation of new collateral capillary

vessels to supply ischemic territories in areas of ischemic penumbra, that is,

the halo surrounding the territory without blood supply.

The vascular and capillary network of the brain is not a rigid system of

branching tubes. Quite on the contrary, as noted earlier, it is an intricate,

flexible, and dynamic system of multidirectional vascular routes connecting

terminal arterioles to venules. The main driving force for regional cerebral

blood flow is the so-called perfusion pressure. This is the difference between

the arterial influx pressure and the outflow pressure in the veins. Cerebral

blood flow has self-regulation mechanisms that maintain a relatively con-

stant blood flow even under the influence of a number of factors. Under

physiological conditions, any change in brain metabolism evokes a blood

flow change of similar amplitude and direction. The brain vascular network

reacts to changes in arterial CO

2

concentration, in ionic (Ca

2+

,K

+

) concen-

tration, and in the interstitial concentration of drugs such as adenosine and