Li S.Z., Jain A.K. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Biometrics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

other applicat ions [1] such as traffic monitoring,

wherein it is mainly used for detecting violations and

monitoring traffic. Typically, video cameras are find-

ing use for detecting congestion, accidents, and in

adaptive switching of traffic lights. Other typical sur-

veillance tasks include portal control, monitoring

shop lifting, and suspect tracking as well as post-

event analysis [ 2].

A traditional surveillance system involves little au-

tomation. Most surveillance systems have a set of cam-

eras monitoring a scene of interest. Data collected from

these sensors are used for two purposes.

1. Real time monitoring of the scene by human

personnel.

2. Archiving of data for retrieval in the future.

In most cases, the archived data is only retrieved after

an incident has occurred.

This, however is changing w ith introduction of

many commercial surveillance technologies that intro-

duce more automation thereby alleviating the need or

reducing the involvement of humans in the decision

making process [3]. Simultaneously, the focus has also

been in visualization tools for better depiction of data

collected by the sensors and in fast retrieval of archived

data for quick forensic analysis. Surveillance systems

that can detect elementary events in the video streams

acquired by several cameras are commercially available

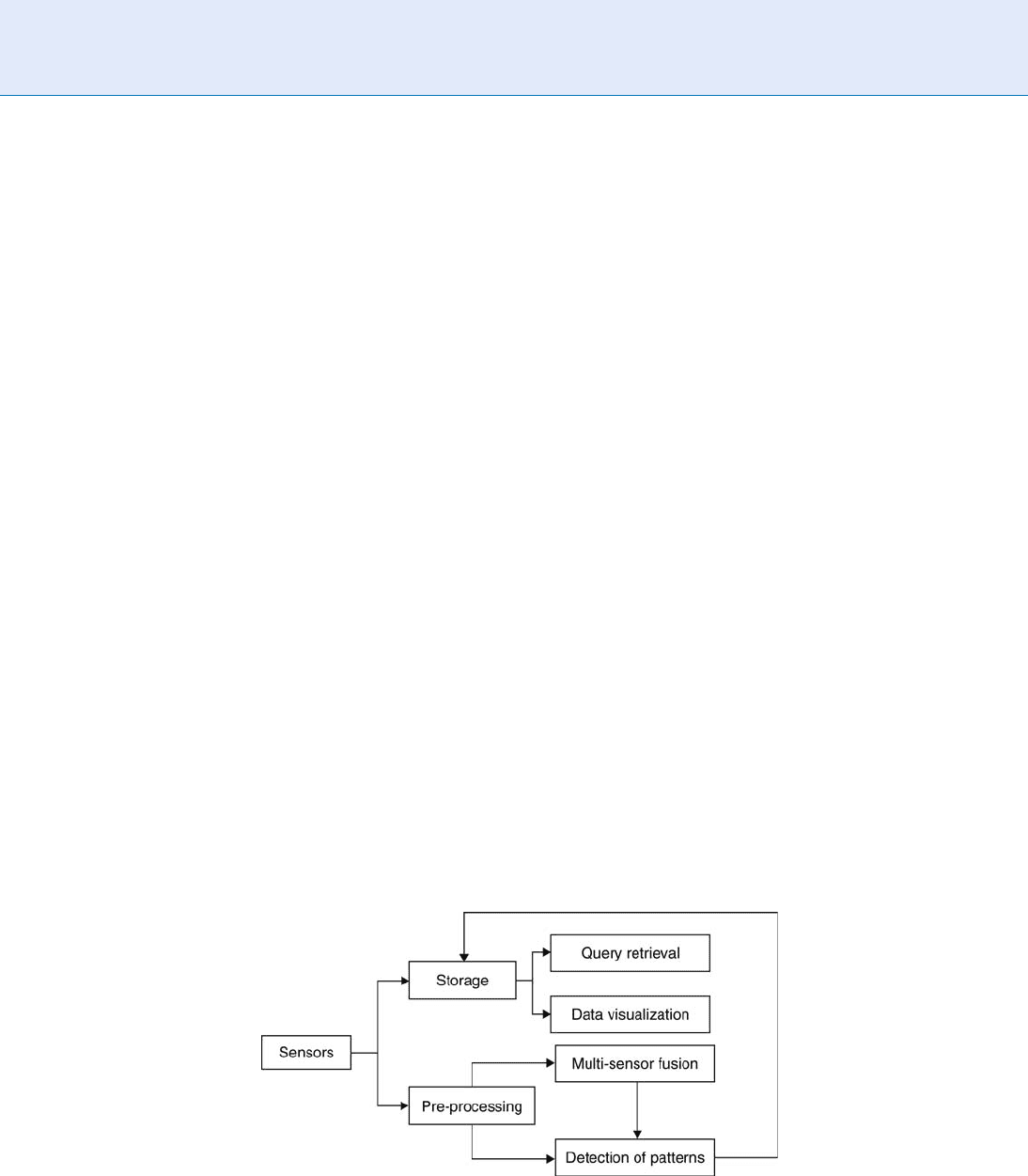

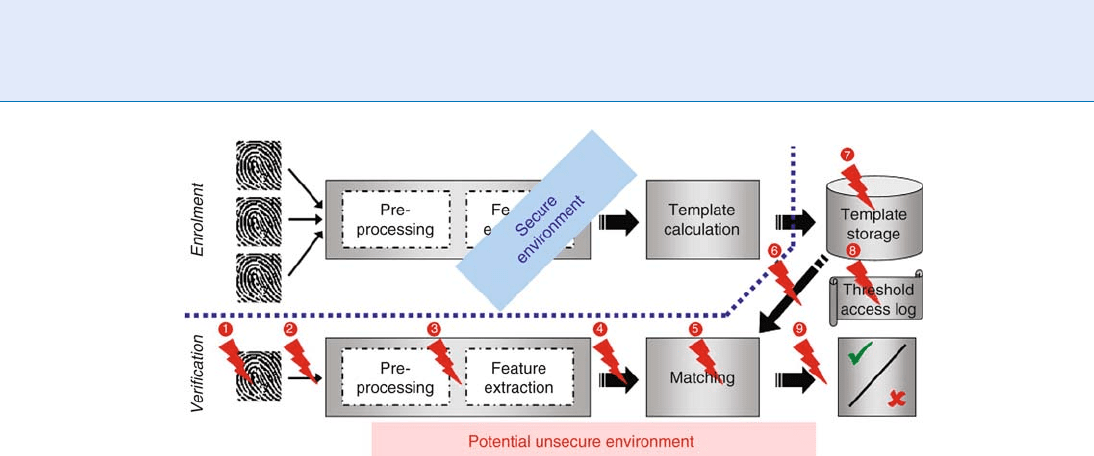

today. A very general surveillance system is schemati-

cally shown in Fig. 1.

Biometrics form a critical component in all

(semi-)automated sur veillance systems, given the

obvious need to a cquire, validate, and process

biometrics in various surveillance tasks. Such tasks

include:

1. Ver ification. Validating a person’s identity is useful

in access control. Typically, verification can be done

in a controlled manner, and can use active

biometrics such as iris, face (controlled acquisi-

tion), speech, finger/hand prints. The system is

expected to use the biometrics to confirm if the

person is truly whom he/she claims to be.

2. Recognition. Recognition of identit y shows up in

tasks of intruder detection and screening, which

finds use in a wide host of scenarios from scene

monitoring to home surveillance. This involves

cross-checking the acquired biometrics across a

list to obtain a match. Typically, for such tasks,

passive acquisition methods are preferred making

face and gait biometrics useful for this task.

3. Abnormality detection. Behavioral biometrics find

use in surveillance of public areas, such as airports

and malls, where the abnormal/suspicious behavior

exhibited by a single or group of individual forms is

the biometric of interest.

Biometrics finds application across a wide range of

surveillance tasks. We next discuss the variates and

trade-offs involved in using biometrics application

for surveillance.

Surveillance. Figure 1 Inputs from sensors are typically stored on capture. The relevant information is searched and

retrieved only after incidents. However, in more automated systems the inputs are pre-processed for events. The system

monitors these certain patterns to occur which initiates the appropriate action. When multiple sensors are present,

for additional robustness, data across sensors might be fused.

1310

S

Surveillance

Biometrics and Surveillance

The choice of biometric to be used in a particular task

depend on the match between the acquisition and pro-

cessing capability of the biometric to the requirements

of the task. Such characteristics include the discrimina-

tive power of the biometric, ease of acquisition, the

permanence of the biometric, and miscellaneous con-

siderations such as acceptability of its use and

▶ privacy

concerns [4, 5]. Towards this end, we discuss some

of the important variates that need be considered in

biometric surveillance.

1. Cooperative acquisiti on. Ease of acquisition is

probably the most important consideration for use of

a particular biometric. Consider the task of home

surveillance, where the system tries to detect intruders

by comparing the acquired biometric signature to a

database of individuals. It is not possible in such a task

to use iris as a biometric, because acquisition of iris

pattern requires cooperation of the subject. Similarly,

for the same task, it is also unreasonable to use con-

trolled face recognition (with known pose and illumi-

nation) as a possible biometric for similar reasons.

Using the cooperation of subject as a basis, allows

us to classify biometrics into two kinds: cooperative and

non-cooperative. Fingerprints, hand prints, speech

(controlled), face (controlled), iris, ear, and DNA are

biometrics that need the active cooperation of the

subject for acquisition. These biometrics, given the

cooperative nature of acquisition, can be collected

reliably under a controlled setup. Such controls could

be a known sentence for speech, a known pose and

favorable illumination for face. Further, the subject

could be asked for multiple samples of the same bio-

metric for increased robustness to acquisition nois e

and errors. In return, it is expected that the biometric

performs at increased reliability with lower false alarms

and lower mis-detections. However, the cooperative

nature of acquisition makes these biometrics unusable

for a variety of operating tasks. None the less, such

biometrics are extremely useful for a wide range of

tasks, such as secure access control, and for controlled

verification tasks such as those related to passports and

other identification related documents.

In contrast, a cquisition of the biometric without

the cooperation of the subject(s) is necessary for sur-

veillance of regions with partially or completely unre-

stricted access, wherein the sheer number of subjects

involved does not merit the use of active acquisition.

Non-cooperative biometrics are also useful in surveil-

lance scenarios requiring the use of behavioral

biometrics, as with behavioral biometrics the use of

active acquisition methods might inherently affect the

very behavior that we want to detect. Face and gait are

probably the best examples of such biometrics.

2. Inherent capability of discrimination. Each bio-

metric depending on its inherent variations across

subjects, and intra-variations for each individual has

limitations on the size of the dataset it can be used

before its operating characteristics (false alarm and

mis-detection rate) go below acceptable limits. DNA,

iris, and finge rprint provide robust discrimination

even when the number of individuals in the data-

base are in tens of thousands. Face (under controlled

acquisition) can robustly recognize with low false

alarms and mis-detections upto datasets containing

many hundreds of individuals. However, performance

of face as a biometric steeply degrades with uncon-

trolled pose, illumination, and other effects such as

aging, disguise, and emotions. Gait, as a biometric

provides similar performance capabilities as that of

face under uncontrolled acquisition. However, as

stated above, both face and gait can be captured with-

out the cooperation of the subject, which makes them

invaluable for certain applications. However, their use

also critically depends on the size of the database that

is used.

3. Range of operation. Another criterion that be-

comes important in practical deployment of systems

using biometrics is the range at whi ch acquisition can

be performed. Gait, as an example, works with the

human silhouette as the basic building block, and can

be reliably captured at ranges upto a 100 m (assuming

a common deployment scenario). In contrast, finger-

print needs contact between the subject and the sensor.

Similarly, iris requires the subject to be at much closer

proximity than what is required for face.

4. Miscellaneous considerations. There exist a host

of other considerations that decide the suitability of

a biometric to a particular surveillance application.

These include the permanence of the biometric, secu-

rity considerations such as the ease of imitating or

tampering , and privacy considerations in its acquisi-

tion and use [4, 5]. For example, the permanence of

face as a biometric depends on the degradation of its

discriminating capabilities as the subject ages [6

, 7].

Surveillance

S

1311

S

Similarly, the issue of wear of the fingerprints with use

becomes an issue for consideration. Finally, privacy

considerations play an important role in the accept-

ability of the biometrics’ use in commercial systems.

Behavioral Biometrics in Surveillance

Behavioral biometrics are very important for surveil-

lance, especially towards identifying critical events be-

fore or as they happen. In general, the visual modality

(cameras) is most useful for capturing behavioral in-

formation, although there has been some preliminary

work on using motion sensor for similar tasks. In the

presence of a camera, the processing of data to obtain

such biometrics falls under the category of event de-

tection. In the context of surveillance systems, these

can be broadly divided into those that model actions of

single objects and those that handle multi-object inter-

actions. In the case of single-objects, an understanding

of the activity (behavior) being performed is of im-

mense interest. Typically, the object is described in

terms of a feature-vector [8] whose representation is

suitable to identify the activities while marginalizing

nuisance parameters such as the identity of the object

or view and illumination. Stochastic models such as

the Hidden Markov models and Linear Dynamical

Systems have been shown to be efficient in modeling

activities. In these, the temporal dynamics of the activ-

ity are captured using state-space models, which form

a generative model for the activity. Given a test activity,

it is possible to evaluate the likelihood of the test

sequence arising from the learnt model.

Capturing the behavioral patterns exh ibited by

multiple actors is of immense importance in many

surveillance scenarios. Examples of such interactions

include an individual exiting a building and driving

a car, or an individual casing vehicles. A lot of other

scenarios, such as abandoned vehicles, dropped objects

fit under this category. Such interactions can be mod-

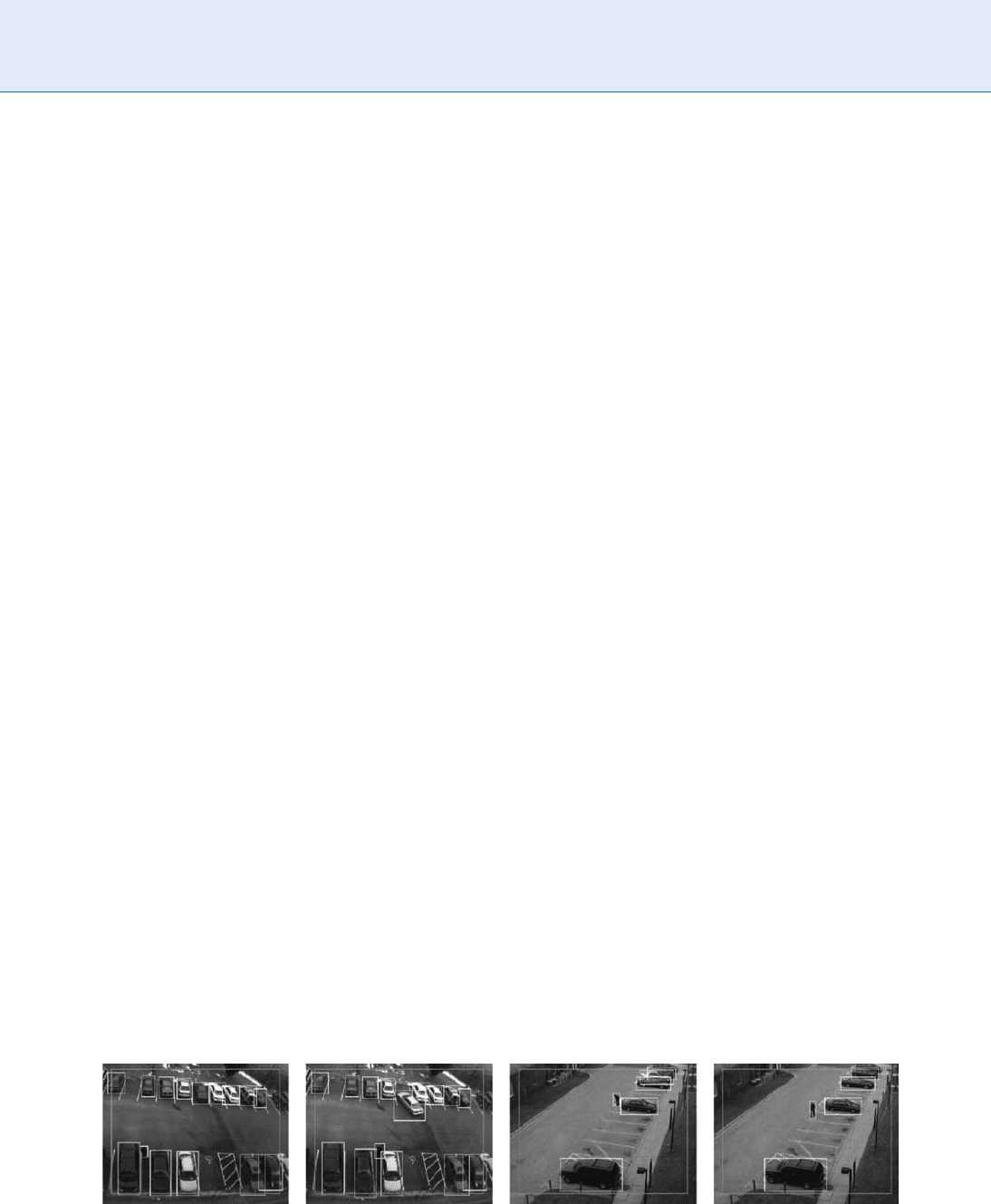

eled using context-free grammars [9, 10](Fig. 2).

Detection and tracking data are typically parsed by

the rules describing the gramm ar and a likelihood

of the particular sequence of tracking information

conforming to the grammar is estimated . Other

approaches rely on motion analysis of humans accom-

panying the abandoned objects.

The challenges towards the use of behavioral

biometrics in surveillance tasks are in making algo-

rithms robust to variations in pose, illumination, and

identity. There is also the need to bridge the gap be-

tween the tools for representation and processing used

for identifying biometrics exhibited by individuals and

those by groups of people. In this context, motion

sensors [11] provide an alternate way for capturing

behavioral signatures of groups. Motion sensors regis-

ter time-instants when the sensor observes motion

in its range. While this information is very sparse,

without any ability to recognize people or disambi-

guate between multiple targets, a dense deployment

of motion sensors along with cameras can be very

powerful.

Conclusion

In summary, biometrics are an important component

of automated sur veillance, and help in the tasks of

recognition and verification of a target’s identity.

Such tasks find application in a wide range of surveil-

lance applications. The use of a particular biometric

for a surveillance application depends critically on the

match between the properties of the biometrics and

the needs of the application. In particular, attributes

Surveillance. Figure 2 Example frames from a detected casing incident in a parking lot. The algorithm described in [10]

was used to detect the casing incident.

1312

S

Surveillance

such as ease of acquisition, range of acquisition and

discriminating power form important considerations

towards the choice of biometric used. In surveillance,

behavioral biometrics are useful in identifying suspi-

cious be havior, and finds use in a range of scene moni-

toring applications.

Related Entries

▶ Border Control

▶ Law Enforcement

▶ Physical Access Control

▶ Face Recognition, Video Based

References

1. Remagnino, P., Jones, G.A., Paragios, N., Regazzoni, C.S.: Video-

Based Surveillance Systems: Computer Vision and Distributed

Processing. Kluwer, Dordecht (2001)

2. Zhao, W., Chellappa, R., Phillips, P., Rosenfeld, A.: Face recog-

nition: a literature survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 35, 399–458

(2003)

3. Shu, C., Hampapur, A., Lu, M., Brown, L., Connell, J., Senior, A.,

Tian, Y.: Ibm smart surveillance system (s3): a open and

extensible framework for event based surveillance. In: IEEE

Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance.

pp. 318–323 (2005)

4. Prabhakar, S., Pankanti, S., Jain, A.: Biometric recognition:

security and privacy concerns. Security & Privacy Magazine,

IEEE 1, 33–42 (2003)

5. Liu, S., Silverman, M.: A practical guide to biometric security

technology. IT Professional 3, 27–32 (2001)

6. Ramanathan, N., Chellappa, R.: Face verification across age

progression. Comput. Vision Pattern Recognit., 2005. CVPR

2005. IEEE Computer Society Conference on 2 (2005)

7. Ling, H., Soatto, S., Ramanathan, N., Jacobs, D.: A study of face

recognition as people age. Computer Vision, 2007. ICCV 2007.

IEEE 11th International Conference on pp. 1–8 (2007)

8. Veeraraghavan, A., Roy-Chowdhury, A.K., Chellappa, R.:

Matching shape sequences in video with applications in

human movement analysis. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach.

Intell. 27, 1896–1909 (2005)

9. Moore, D., Essa, I.: Recognizing multitasked activities from

video using stochastic context-free grammar. Workshop on

Models versus Exemplars in Computer Vision (2001)

10. Joo, S., Chellappa, R.: Recognition of multi-object events using

attribute grammars. IEEE International Conference on Image

Processing pp. 2897–2900 (2006)

11. Wren, C., Ivanov, Y., Leigh, D., Westhues, J.: The MERL

Motion Detector Dataset: 2007 Workshop on Massive Datasets.

(Technical report)

SVM

▶ Support Vector Machine

SVM Supervector

An SVM (Support Vector Machine) is a two class classi-

fier. It is constructed by sums of kernel function K(.,.):

f ðxÞ¼

X

L

i¼1

a

i

t

i

Kðx; x

i

Þþd ð1Þ

t

i

are the ideal outputs (−1 for one class and +1 for the

other class) and

P

L

i¼1

a

i

t

i

¼ 0ða

i

> 0Þ The vectors x

i

are

the support vectors (belonging to the training vectors)

and are obtained by using an optimization algorithm.

A class decision is based upon the value of f (x)

with respect to a threshold. The kernel function

is constrained to verify the Mercer condition:

Kðx; yÞ¼bðxÞ

t

bðyÞ; where b(x) is a mapping from

the input space (containing the vectors x) to a possibly

infinite-dimensional SVM expansion space.

In the case of speaker verification, given universal

background (GMM UBM):

gðxÞ¼

X

M

i¼1

o

i

Nðx; m

i

; S

i

Þ; ð2Þ

where, o

i

are the mixture weights, N() is a Gaussian,

andðm

i

þ S

i

Þare the means and covariances of

Gaussian components. A speaker (s) model is a

GMM obtained by adapting the UBM using MAP

procedure (only means are adapted: ðm

s

Þ). In this

case the kernel function can be written as:

Kðs

1

; s

2

Þ¼

X

M

i¼1

ð

ffiffip

o

i

S

ð1=2Þ

i

m

s

1

i

Þ

t

ð

ffip

o

i

S

ð1=2Þ

i

m

s

2

i

Þ:

ð3Þ

The kernel of the above equation is linear in the GMM

Supervector space and hence it satisfies the Mercer

condition.

▶ Session Effects on Speaker Modeling

SVM Supervector

S

1313

S

Sweep Sensor

It refers to a fingerprint sensor on which the finge r

has to sweep on the platen during the capture.

Its capture area is very small and it is represented by

few pixel lines.

▶ Fingerprint, Palmprint, Handprint and Soleprint

Sensor

Synthesis Attack

Synthesis attack is similar to replay attack in that it also

involves the recording of voice samples from a legiti-

mate client. However, these samples are used to build a

model of the client’s voice, which can in turn be used

by a text-to-speech synthesizer to produce speech that is

similar to the voice of the client. The text-to-speech

synthesizer could then be controlled by an attacker, for

example, by using the keyboard of a notebook com-

puter, to produce any words or sentences that may be

requested by the authentication system in the client’s

voice in order to achieve false authenticati on.

▶ Liveness Assurance in Face Authentication

▶ Liveness Assurance in Voice Authentication

▶ Security and Liveness, Overview

Synthetic Biometrics

▶ Biometric Sample Synthesis

Synthetic Fingerprint Generation

▶ Fingerprint Sample Synthesis

▶ SFinGe

Synthetic Fingerprints

▶ Fingerprint Sample Synthesis

Synthetic Iris Images

▶ Iris Sample Synthesis

Synthetic Voice Creation

▶ Voice Sample Synthesis

System-on-card

Smartcard has complete biometric verification system

which includes data acquisition, processing, and

matching.

▶ On-Card Matching

1314

S

Sweep Sensor

T

Tablet

▶ Digitizing Tablet

Tamper-Proof

The term tamper-proof refers to as a functionality of

a device that enables the system to resist and/or pro-

tect itself from tampering acts. This functionality

sometimes implemented as a combination of a self-

destruction mechanism and sensors that detect any

unauthorized access to the device including vandalism.

This functionality is also known as temper-resistant or

anti-tampering.

▶ Finger Vein Reader

Tamper-proof Operating System

RAUL SANCHEZ-REILLO

University Carlos III of Madrid; Avda. Universidad,

Leganes (Madrid), Spain

Synonyms

Malicious-code-free Operating System; Secure Bio-

metric Token Operating System

Definition

Operating System with a robust design, as not to allow

the execution of malicious code. Access to internal data

and procedures are never allowed without the proper

authorization. In its more strict implementations, this

Operating System will have attack detection mechan-

isms. If the attack is of a certain level, the Operating

System may even delete all its code and/or data.

Introduction

The handling of sensible data in Information Systems

is currently very usual. Which data is to be considered

sensible is up to the application, but at least we can

consider those such as personal data, financial data as

well as access control data. Actors dealing with such

Information System (clients/citizens, service providers,

integrators, etc.) have t o be aware of the security level

achieved within t he system.

Although this is a very important issue in any system,

when biometric information is handled it becomes a

critical point. Reason for this is that biometric informa-

tion is permanently valid, as it is expected to be kept the

same during the whole life of a person. While a private

key can be changed as desired and eve n cance lled, a user

cannot change his fingerpri nt (unless changing finger) or

even cancel it. If cancelling biometric raw data, the user

will be limited, in case of fingerprints, to 10 succ essful

attacks during his/her whole life. These kind of consid-

erations has already been published even back to 1998, as

it can be read in [1].

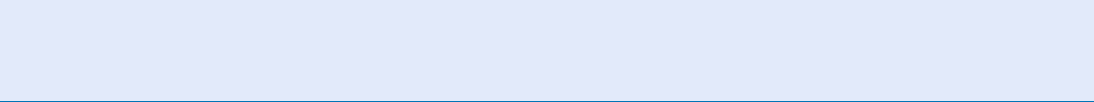

Therefore, biometric systems have to be kept as

secure as possible. There are several Potential Vulnera-

ble Points (PVPs) in any Biometric System, as it can be

seen in Fig . 1. All those 9 PVPs have to be considered

when designing a biometric solution. A good introduc-

tion to threats in a Biometric System can be found in

[2, 3], and in BEM [ 4].

PVP 1 has to deal with user attitudes, as well as

capture device front end. Regarding user attitude,

an aut horised user can provide his own biome-

tricsample to an impostor unknowingly, unwill-

ingly, or even willingly. From the capture device

#

2009 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

front-end point of view, such device may not be

able to:

– Detect a nonlive sample

– Detect the quality of the input sample, being able

to discard those under a determined threshold

– Protect the quality threshold against manipulation

– Detect degradation of its own degradation

– Resist environmental factors

– Eliminate residual information from previous

captures

– Detect and discard sample injection

– Deny successive and fast sample presentation

PVP 2 is directly related to the threat group 3 of

BEM. It is basically focused on the capture device

back-end, as well as the front-end of the Biometric

Algorithm. Captured sample could be intercepted

and/or reinjected, to provide a

▶ replay attack.

Major problem relies on the potential lost of the

user’s biometric identity. Also, another threat is a

▶ hill-climbing attack by injecting successive bio-

metric samples.

PVPs 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8 could be treated as in any

other IT system (Trojans, Viruses, communications

interception, data injection, hill climbing attacks,

etc.). So the same kind of study shall be done.

It is in this kind of PVPs where a Tamper-proof

Operating System can be of help. It is important to

note that sensibility related to biometric related

information, covers not only the sample data, fea-

ture vectors, and templates, but also thresholds,

access logs, and algorithms.

PVP 5, being also a typical point of study in any IT

system, has here more importance depending on

the information that could be given by the system

after the matching. If matching result is not given

just by an OK / ERROR me ssage, but also carries

information about the level of matching acquired,

this could be used by an attacker to build an artifi-

cial sample, by hill-climbing techniques. For this

PVP also, the Tamper-proof O.S. can play an im-

portant role.

Biometric Devices

Regarding Biometr ics, a Tamper-proof Operating Sys-

tem is intended to be running in some (or any) ele-

ments which are part of the Biometric System. The idea

of this kind of Operating Systems is not new, as they

are already implemented in other areas, such as

▶ smart cards for financial services. This kind of

electronic devices are designed under a basic security

rule: ‘‘Not only the device has to work under its con-

strained conditions of user, but also has to stop work-

ing outside those conditions’’. In few words, this means

that, for example, if the smart card is expected to work

with a supply voltage from 4.5 to 5.5 volts, it does not

have to work outside the range (e.g., if supply voltage is

4.4 or 5.6, not even a response has to be obtained from

the card). Related to the Operating System inside the

card, this covers things like not allowing the execution

of any undefined/undocumented command, or not

Tamper-proof Operating System. Figure 1 Potential vulnerable points in a Biometric System where Enrolment is

considered secured.

1316

T

Tamper-proof Operating System

being able to install new functions that can behave as

Trojan Horses or Viruses.

With this example, the reader can think that

this kind of products does not really exist, because

several papers have been published related to secu-

rity problems with smartcards (e.g., [5] and some

general audience press). It has to be stated that not all

times an integrated circuit identification card is re-

ferred, it is really a smartcard (i.e., a microprocessor-

based identification card with a tamper-proof O.S.).

Also, some real smartcards have not been properly

issued, leaving some critical data files unprotected,

or not using the secur ity mechanisms provided. Rules

to be followed to properly use a smartcard can be

found in [6].

This same kind of rules can be applied to all kind of

biometric devices. Obviously, depending on the system

architecture, biometric devices can be of very different

kinds. Figure 2 shows two possible architectures of a

biometric authentication system, which are usually

known as (a) match-off-card (also known as match-off-

token), and (b) match-on-card (or match-on-token).

Apart from these two, many other schemes can be

designed. The term ‘‘match’’ should be changed for

‘‘Comparison’’. So instead of ‘‘match-off-card’’, ‘‘off-

card biometric comparison’’ should be used. But w ith-

in text ‘‘match-off-card’’ and ‘‘match-on-card’’ are

used due to being terms w idely used among the

industry.

In a match-off-card system (e.g., [7]), we can con-

sider a simplification of the system as composed of

three devices: the capture device, the token or card

where the user’s template is stored, and the rest of the

system, which will be named as ‘‘Biometric System’’.

Major difference with the match-on-card system (e.g.,

[8]) is that here the token only stores the user’s tem-

plate, while in the match-on-card version it also per-

forms some biometric-related computations.

In any case, any of those devices should be designed

following the rules given below regarding a Tamper-

proof O.S. Being this viable, if those devices are devel-

oped as embedded systems, major problems can arise

when one of those devices (t ypically the Biome tric

System) is running on a general purpose computer,

where little or no control is available for installed

applications and data exchange.

Tamper-proof Operating System. Figure 2 Some architectures of biometric authentication systems, splitting tasks in

several devices.

Tamper-proof Operating System

T

1317

T

Requirements for a Tamper-Proof O.S.

Once focused the environment where a Tamper-proof

O.S. has to be found in Biometric Dev ices, it is time to

start its design. A good starting point will be following

all previous works dealing with smart cards. The rea-

son for that is to transfe r the know–how of near 30

years of secure identification tokens given by the smart

card industry [ 9]. This same ideas can be extrapolated

to other biometric devices, not only personal tokens.

First thing to consider when designing a Tamper-

proof O.S. is the different life phases that the biometric

device w ill have. All devices, specially those related to

personal authenticati on, should go through different

life stages, from manufacturing to its use by the end

users. As informati on handled by them is really sensi-

ble, extra protection should be taken to avoid robbery,

emulation, or fraudulent access to the device or its

information. Therefore, securit y mechanisms will be

forced in each life stage. Those mechanisms are mainly

based on Transp ort Keys, which protect access to using

the device in each change of its life phase. Life phases

defined are:

Manufacturing: where the device is assembled. The

microcontroller within the device should be pro-

tected by a Transport Key, before delivered to the

next stage. The way to compute that Transport Key

for each microcontroller, will be sent to the com-

pany responsible of the next phase by a separate

and secured way.

Personali zation: In this phase, each device is differ-

entiated from all others by storing some unique

data related to the final application, user, and access

conditions. Some times this phase is split in several

subphases, specially when the device has to be per-

sonalized for the application (prepersonalization)

and then for the final user (personalization), as it

may happen with identification tokens. In this

phase, also Data Structure regarding the applica-

tions may be created, as well as the full security

architecture.

Usage: The end user is ready to use the device.

Discontinuation: Due to ageing, limited time use,

accidents, or attack detection, the device may be out

of use. This can be temporary (for example, when

keys are blocked), or permanent (no re-activation is

allowed). It has to be guaranteed that once discon-

tinued, such device shall not be able to be used.

Entering in details regarding the requirements for a

tamper-proof operating system, we can state the fol-

lowing general rules:

Mutual Authentication mechanisms have to be

used before exchanging any kind of biometric

information. In any communication, both parts

have to be sure that the other party is a reliable one.

To avoid ▶ replay attacks, some time-stamping-like

mechanisms have to be used (e.g., generation of

session keys to sign/cipher each message exchanged).

Only the manufactured designed commands can

be executed. No possibility of downloading new

commands has to be allowed. Therefore, flash rep-

rogramming and device updating are strongly

discouraged.

Before executing anything in the biometric device,

full integrity check (both cryptographic and se-

mantic) of the command and its data has to be

performed. Some attacks would try to exploit un-

defined cases in the semantics of a command

exchanged.

All sensible data (sample data, feature vectors,

templates, and thresholds) has to be transmitted

ciphered.

If there is a command related to changing pa-

rameters, it has to be sent with all security mech-

anisms allowed, as the system can be even more

vulnerable to attacks related to changing those para-

meters (e.g., quality or verification thresholds).

Feedback information from the device to the exter-

nal world has to be as short as possible to avoid hill-

climbing attacks. For example, a device performing

comparisons in an authentication system has to

provide only a YES/NO answer, but not giving

information on the matching score obtained.

Attack detection mechanisms have to be consid-

ered. If an attack is detected, then the device has to

stop working, and a reinitialization has to be made.

If the detected attack is consider extremely serious,

the device may consider dele ting not only all tem-

poral data, but also its permanent data or even it

programming code.

Successive failed attempts to satisfy any security

condition has to be considered as an attack, and

therefore, the device has to be blocked, as it hap-

pens with a PIN code in a smartcard.

No direct access to hardware resources (e.g., mem-

ory addresses, communication ports, etc) can be

1318

T

Tamper-proof Operating System

allowed. Most virus and Trojan horses benefit for

not following this rule.

As soon as data is no longer needed by the

Operating System, it has to be erased as to prevent

latent data to be acquired in a successful attack.

Most of these requirements can be satisfied by defining

a security architecture based on cryptographic algorithms.

Several implementations can be followed. If the developer

is not familiar with these mechanisms, it is suggested

to follow the secret codes/secret keys architecture of a

smartcard, and the Secure Messaging mechanism [6, 9].

These can be directly applied to personal Tokens, and

upgraded to other kind of biometric devices.

Example of an O.S. Instruction Set

When implementing a Tamper-proof O.S. several

design decisions have to be made: Frame formats,

time-outs, number of retries, etc. All these issues

depend on the communication strategy followed by

the whole biometric system. Therefore, no general

rule can be given to the designed.

Regarding the instruction set, a minimal list of

functions can be considered, depending on the dev ice

where the O.S. is to be included. This is also dependent

on the platform chosen. As an example, the instruction

set for a limited-resources platforms is given. This

instruction set has been proposed to ISO/IEC JTC1/

SC37 to be considered as a lighter version of BioAPI,

the standardized Application Program Interface for

biometric applications. This lighter version is called

BioAPI Lite and is being standardized as ISO/IEC

29164.

Commands needed by a limited biometric device,

depends on the functionality of such device. Obviously

is not the same a capture device, than a personal token.

But in general terms these commands can be classified

in fo ur major groups: Module Management, Template

Management, Biometric Enrolment, and Biometric

Process.

Management Commands relate to manage the

overall module behavior. Four commands can be con-

sidered in this group:

Initialize: Tells the module to initialize itself, open-

ing the offered services and initialize all secu rity for

ciphered data exchange. This command is to be

called any time a session is started (power on,

session change, etc). Without being called, the rest

of the commands shall not work.

Close: Tells the module to shutdown.

Get Propertie s: Provides information on capabil-

ities, configuration, and state.

Update Parameters: Updates parameters in mod-

ule. One of such parameters can be the comparison

threshold. For that reason, this function is recom-

mended to be used with all security mechanisms

available.

Template Management Commands refer to those

functions needed to store and retrieve templates from

the module. These functions will be supported by those

modules that are able to store users’ templates. These

set of commands are expected to be used by personal

tokens or small databases. The functions defined are:

Store Template: Stores the input template in the

internal biometric module database.

Retrieve Template: Obtain the referenced template

from the biometric module.

The next group is the Biometric Enrolment Com-

mands. This group of functions will be considered in

systems where enrolment is to be made internally. Due

to the different process of enrolment, even for a single

biometric modality (e.g., different number of samples

needed), in limited devices a multi step procedure

is suggested. First, user will call functions related to

obtain samples for the enrolment and then a call to

the Enrol function will have to be done. Commands

defined are:

Capture for Enrol: Performs a biometric capture

(using onboard sensor), keeping the information in

module for later enrolment process. The number

this function is called depends on the number of

samples the module needs to perform enrolment.

As this operation involves user interaction, biomet-

ric module manufacturer shall consider time-out

values to cancel operation, reporting that situation

in the Status code returned.

Acquire for Enrol: Receives a biometric sample

to keep the information in module for later enro-

lment process. The number this function is called

depends on the number of samples the module

needs t o perform enrolment. Depending on mod-

ule capabilities, input data can be a raw sample,

a prepro cessed one, or its corresponding feature

vector.

Tamper-proof Operating System

T

1319

T